1. Introduction

Heat treatment of steels is one of the most critical and widely practiced manufacturing processes, enabling precise control over the microstructure and mechanical properties through carefully designed thermal cycles involving austenitization, controlled cooling, and tempering operations [

1]. This process exploits phase transformations in the iron–carbon system by manipulating the decomposition of austenite into various products, including martensite, bainite, ferrite, and pearlite, each conferring distinct mechanical characteristics ranging from ultra-high strength to excellent ductility [

2]. This microstructural control underpins countless engineering applications, including automotive components requiring balanced strength and toughness, aerospace alloys demanding exceptional fatigue resistance, structural steels providing construction reliability, and tooling steels offering wear resistance and hardness retention [

3].

Despite its industrial significance, with the global heat treatment industry processing over 50 million metric tons of steel annually and representing market values exceeding

$80 billion, the optimization of heat treatment processes remains predominantly empirical [

4]. Industrial practice relies heavily on accumulated experience, trial-and-error experimentation, and time–temperature–transformation (TTT) or continuous cooling transformation (CCT) diagrams developed through extensive experimental campaigns [

5]. A typical alloy development program requires 50–200 heat treatment trials with associated metallographic analysis, hardness testing, tensile testing, and impact testing, representing investments of

$100,000–500,000 and development timelines spanning 6–18 months [

6,

7]. This inefficiency stems from the high-dimensional parameter space governing transformation outcomes: the chemical composition varies across 10+ alloying elements; austenitizing conditions involve temperature–time combinations; cooling profiles span five orders of magnitude from air cooling to severe water quenching, and tempering treatments offer wide temperature–time permutations [

8].

The emergence of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence has catalyzed a paradigm shift in materials science, offering powerful capabilities to identify complex nonlinear relationships in high-dimensional datasets, where traditional physics-based modeling faces challenges in identifying such relationships [

9,

10]. ML algorithms excel in pattern recognition tasks involving multiple coupled variables and nonlinearities that lack closed-form analytical solutions, making them particularly well-suited for predicting material properties [

11]. The materials science community has witnessed remarkable successes, including crystal structure prediction, which enables material discovery [

12], accelerated screening of thermoelectric materials [

13], catalyst design for energy applications [

14], and high-entropy alloy development [

15]. These achievements demonstrate ML’s potential of ML to transform materials development from slow experimental iterations to rapid computational predictions.

However, a fundamental constraint limits the adoption of ML in steel heat treatment applications: critical data scarcity [

16]. Comprehensive experimental datasets spanning composition, processing parameters, microstructure, and properties are extremely rare. Several factors contribute to this shortage. First, industrial heat treatment data represent competitive intellectual property that companies guard closely, making public sharing uncommon [

17]. Second, historical experimental studies often lack consistent documentation of critical parameters, such as the exact austenitizing temperatures, cooling rates, and prior thermal history, reducing their utility for ML training [

18]. Third, published research typically focuses on specific steel grades under narrow processing windows driven by targeted investigations rather than systematic dataset generation [

19]. Fourth, the prohibitive cost of generating comprehensive datasets at the scales required for robust ML training (typically >1000 samples) creates practical barriers for academic and industrial research groups [

20,

21].

The largest publicly available steel property database (MatWeb) contains fewer than 5000 entries across all steel grades, most of which lack the complete processing history documentation necessary for predictive modeling [

22]. Leading ML studies in materials science typically employ datasets exceeding 10,000 samples for reliable model training and validation, creating a critical gap between the available data and the methodological requirements [

23,

24]. This data bottleneck has motivated the exploration of alternative strategies, including transfer learning from related material systems, active learning for strategic experimental design, physics-informed neural networks incorporating domain knowledge through specialized loss functions, and synthetic data generation [

25,

26,

27]. Recent ML applications for steel property prediction have demonstrated promising results despite data limitations, thereby validating the viability of this approach. Xiong et al. trained random forest models on 1200 experimental data points, achieving R

2 = 0.89 for yield strength prediction across various steel grades [

8]. Wen et al. applied neural networks to high-entropy alloy datasets comprising 800 compositions and reported an R

2 of 0.92 for hardness prediction [

15]. Zhang et al. employed gradient boosting on 950 high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steel samples and obtained R

2 = 0.87 for the tensile strength prediction [

28]. While these studies demonstrate the feasibility of ML for material property prediction, all researchers have consistently highlighted data acquisition as the primary bottleneck limiting broader adoption and improved accuracy of the models. Recent machine learning studies demonstrate feasibility despite data limitations (

Table 1). Xiong et al. [

8] applied random forest regression to 360 carbon and low-alloy steel samples from the Japan National Institute of Material Science (NIMS) database, predicting fatigue strength, tensile strength, fracture strength, and hardness. Wen et al. [

15] used neural networks on 800 high-entropy alloy compositions, achieving R

2 = 0.92 for hardness prediction. While these studies validate ML potential for material property prediction, researchers consistently cite data acquisition as the primary bottleneck limiting broader adoption and improved accuracy.

An emerging and potentially transformative strategy to address data scarcity is synthetic data generation, which involves creating training datasets via computational simulations based on validated physical principles, rather than requiring extensive experimental measurements [

28,

29,

30]. This approach leverages the extensive theoretical frameworks developed over eight decades of steel metallurgy research, where robust quantitative relationships exist; however, integration with modern ML methods remains underdeveloped [

31]. For steel heat treatment, well-established theories enable the generation of synthetic data across multiple physical scales and transformation mechanisms.

At the thermodynamic level, CALPHAD (CALculation of PHAse Diagrams) databases provide equilibrium phase compositions and transformation temperatures for multicomponent alloys with prediction accuracies within ±10–20 °C of experimental measurements [

32,

33]. Commercial implementations, including Thermo-Calc, JMatPro, FactSage, and PANDAT, have achieved validation success rates exceeding 90% for ferrous systems [

34]. At the kinetic level, phase transformation rates are governed by mathematical models validated over six decades: the Johnson–Mehl–Avrami equations describe diffusional transformations with composition-dependent parameters [

13]; the Koistinen–Marburger relationships predict martensitic transformation fractions [

35]; and the Burke–Turnbull equations model austenite grain growth kinetics [

36]. At the property level, extensive empirical correlations connect the microstructure to the mechanical performance, such as phase-weighted hardness calculations with composition corrections, Pavlina–Van Tyne hardness–strength conversions validated on >500 steels, and Hall–Petch relationships quantifying grain size effects [

37,

38]. The validity of synthetic data approaches has been demonstrated across diverse material domains, establishing a proof-of-concept for theory-guided machine learning. Kaufman and Ågren demonstrated that CALPHAD-generated phase equilibrium datasets enable accurate ML predictions of phase stability in complex multicomponent alloys [

16]. Ward et al. utilized density functional theory (DFT) calculations to generate training data for inorganic compound property prediction, achieving accuracy comparable to experimental databases while dramatically reducing data collection costs [

17]. Most relevant to steel applications, preliminary studies have suggested that synthetic datasets can capture fundamental composition-property trends, although comprehensive validation, including systematic algorithm comparison, physical consistency verification, and industrial applicability assessment, remains limited [

8].

This study developed and validated a comprehensive machine learning framework for predicting the microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of heat-treated steels using gradient boosting algorithms trained exclusively on synthetic data generated from established metallurgical principles. Our study addresses critical gaps in the existing literature through a systematic investigation across multiple dimensions. We generated a 400-sample synthetic dataset encompassing eight commercial AISI steel grades, spanning low-carbon structural steels to hypereutectoid bearing steels, and covering the industrial heat-treatment parameter ranges. We conducted a rigorous comparison of four supervised learning algorithms (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Support Vector Regression, Neural Networks) following comprehensive hyperparameter optimization via a 5-fold cross-validation grid search. We analyzed feature importance using multiple methods to identify the dominant processing parameters and validate their alignment with the metallurgical understanding. We demonstrated physical consistency through literature benchmarking, monotonicity verification, and limit behavior analysis. Finally, we assessed the practical applicability of the model through learning curve analysis, quantification of data requirements, and residual analysis.

4. Discussion

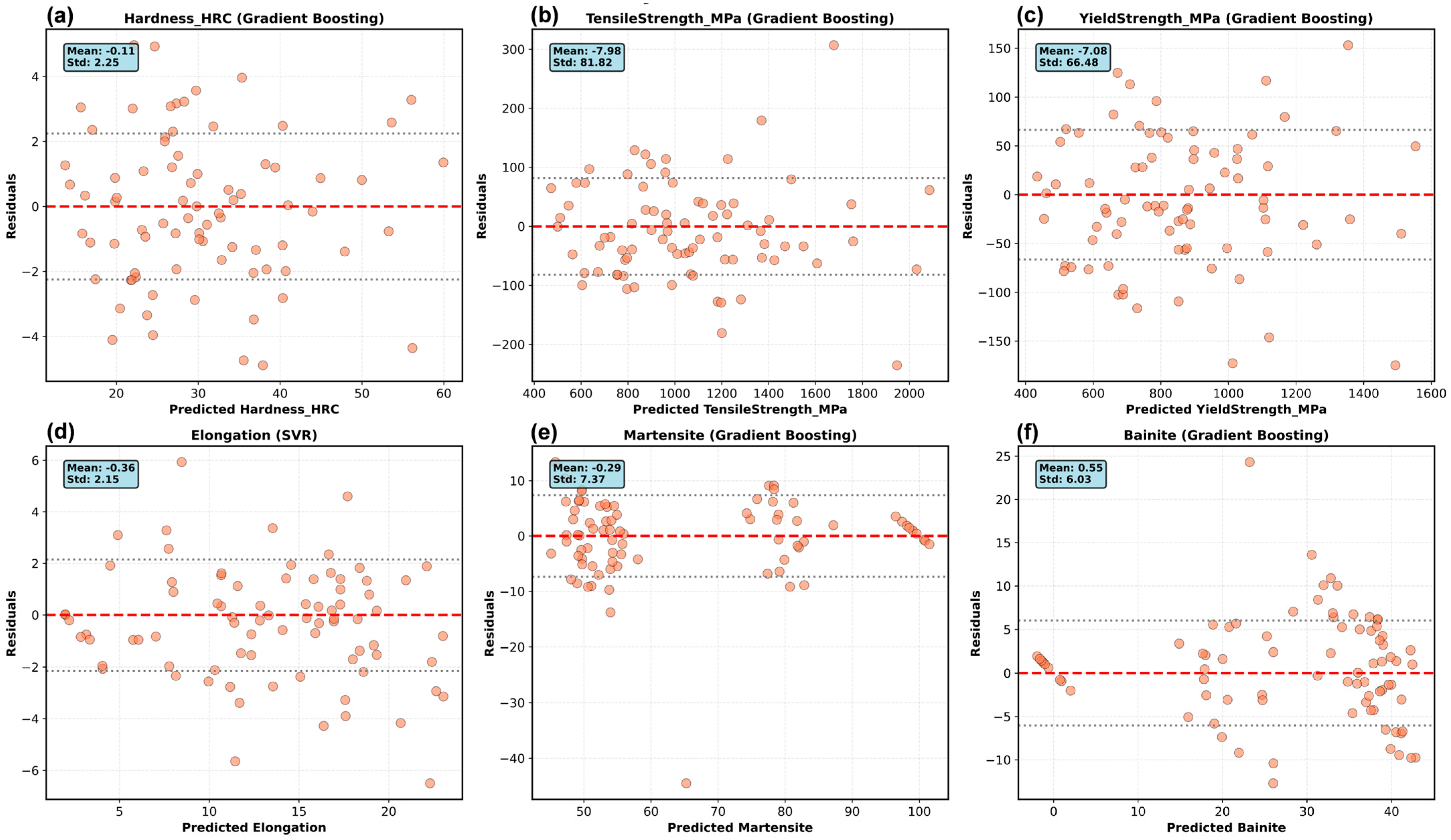

The synthetic data generation framework relies on empirical relationships with compositional validity boundaries that affect the prediction accuracy. The Koistinen-Marburger equation (Equation (2)) for martensite start temperature, originally developed for plain carbon steels, shows mean absolute error of ±25 °C for carbon content between 0.2–0.6% but accuracy degrades to ±40 °C for hypereutectoid compositions such as AISI 52100 (1.0% C) [

32,

33]. This temperature deviation translates to martensite fraction prediction errors of 5–8% via Equation (3). Similarly, the Grossmann hardenability relationships (Equation (1)) remain valid within our compositional range, as the maximum total alloying content is 4.85% (AISI 4340: 0.4% C + 0.7% Mn + 0.8% Cr + 1.8% Ni + 0.25% Mo), which falls within the validated limit of <5% total alloying. The Pavlina-Van Tyne hardness-strength correlation (Equation (6)) is validated for 20–65 HRC with ±10% standard error, fully encompassing our predicted range of 17–64 HRC. These limitations explain why medium-carbon alloy steels (4140 and 4340) show slightly higher prediction accuracy than the boundary compositions (1020 and 52100). Hence, this study demonstrates that data generated from established metallurgical theories enable the training of high-accuracy machine learning models for steel heat treatment property prediction. The critical cooling rate threshold approach (Equations (1a) and (1b)) simplifies continuous cooling transformation behavior was simplified into discrete regimes, introducing systematic errors where multiple transformation products formed simultaneously. Analysis by cooling rate category reveals that microstructural predictions achieve higher accuracy under extreme conditions: slow cooling (<10 °C/s, predominantly ferrite-pearlite formation) and severe quenching (>100 °C/s, predominantly martensite formation) show better agreement with expected outcomes, whereas intermediate cooling rates (10–50 °C/s), where martensite, bainite, and ferrite compete, exhibit increased prediction variance. This reflects the inability of simple threshold models to capture overlapping transformation curve noses and the competitive nucleation kinetics that occur during continuous cooling through multiple transformation regions. More sophisticated approaches that incorporate explicit Johnson–Mehl–Avrami kinetics or CALPHAD-coupled transformation models would improve the phase fraction accuracy but would require commercial software integration and substantially increase the computational cost, representing a trade-off between simplicity and precision [

34,

35]. Gradient boosting achieved R

2 > 0.93 for the primary mechanical properties, with prediction errors (hardness of 2.38 HRC and 88 MPa tensile strength) within the typical experimental measurement uncertainty. This performance matches or exceeds recent ML studies using experimental data. Xiong et al. [

8] achieved R

2 up to 0.85 for various mechanical properties using random forest on 360 carbon and low-alloy steel samples from the NIMS database. Wen et al. [

15] obtained R

2 = 0.92 for hardness prediction on 800 high-entropy alloy compositions using neural networks. Our results suggest that synthetic data approaches, when grounded in mature theoretical frameworks, can substitute scarce experimental datasets without sacrificing the prediction accuracy. This success stems from three factors. First, eight decades of heat treatment research have produced robust quantitative relationships, including Koistinen–Marburger martensite kinetics [

14], Grossmann hardenability [

15], and Hollomon-Jaffe tempering [

21], which have been validated across hundreds of compositions and conditions. These theories capture the essential physics, enabling accurate predictions within the validated ranges. Second, hierarchical causality (composition + processing → microstructure → properties) permits sequential modeling, wherein transformation outputs become property inputs, facilitating validation at each level. Third, industrial heat treatment operates within well-defined parameter spaces established through a century of practice, enabling confident interpolation without risky extrapolations.

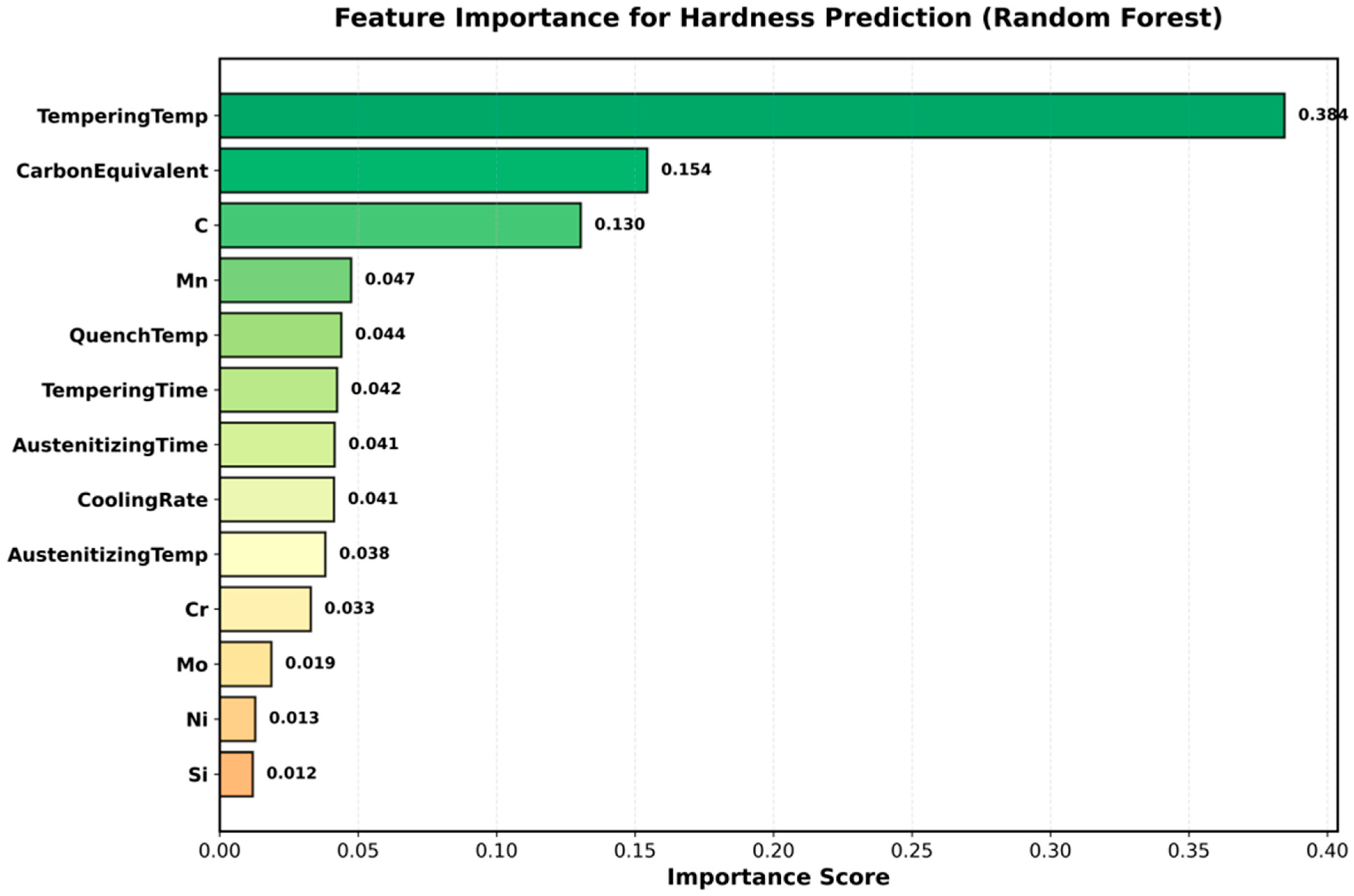

Gradient boosting’s 7–13% performance advantage over random forest derives from sequential error correction explicitly targeting residuals from previous trees through gradient descent optimization. This enables efficient learning from difficult samples, particularly extreme compositions (hypereutectoid 52100 and low-hardenability 1020), which exhibit complex behaviors. The adaptive learning rate (optimized to 0.1) prevented overfitting while allowing proportional contributions from the strong learners. Shallow trees (depth 5) capture the main effects without overfitting leaves, with complexity arising from many trees rather than deep trees. Hyperparameter optimization improved the performance by 12–15%, underscoring the necessity of tuning production models. The optimized gradient boosting hyperparameters (150 estimators, learning rate 0.1, maximum depth 5, subsample 0.8) were determined through a systematic grid search with 5-fold cross-validation on our specific steel heat treatment dataset. These settings achieved a 12–15% performance improvement over the default configuration. However, the transferability of these hyperparameters to other alloy systems or heat treatment processes generated under different assumptions should not be assumed. Different material systems may exhibit different complexity patterns, requiring architectural adjustments: aluminum age-hardening involves simpler precipitation kinetics, potentially requiring shallower trees (depth 3–4), whereas titanium alpha-beta transformations involve more complex morphological evolution, potentially benefiting from deeper trees (depth 6–7). We recommend performing independent hyperparameter optimization for new material systems using cross-validation on representative training data rather than directly transferring optimized values across domains. Feature importance analysis validated the synthetic data quality through concordance with the metallurgical understanding. The 38.4% dominance of the tempering temperature reflects its control of hardness via carbide precipitation, retained austenite transformation, and cementite coarsening in the 200–600 °C range. The combined carbon features (28.4%) confirmed the role of carbon as a fundamental strengthening element through martensitic tetragonality and carbide volume fractions. The observed feature importance pattern (tempering temperature 38.4%, carbon equivalent 15.4%, carbon 13.0%) reflects both genuine metallurgical significance and the influence of the stratified sampling design. Our intentional parameter decorrelation (line 253) ensures the independent variation in processing variables and composition, enabling robust model training across the full parameter space. However, this approach may amplify the apparent importance of processing parameters compared to industrial datasets, in which parameters naturally couple through equipment constraints and production recipes. For example, in industrial practice, the tempering temperature and time often correlate (r ≈ 0.4–0.6) through fixed tempering parameter targets, whereas our synthetic data exhibit a near-zero correlation (r < 0.1). Despite this design choice, the dominance of the tempering temperature aligns with the fundamental heat treatment understanding, as it directly controls the carbide precipitation and martensite decomposition kinetics, governing the final hardness across all steel grades. The 54.6% processing versus 45.4% compositional split validates the power of heat treatment in tailoring properties across modest compositional variations. This alignment provides confidence that the models learn genuine physical relationships rather than spurious correlations from algorithmic artifacts.

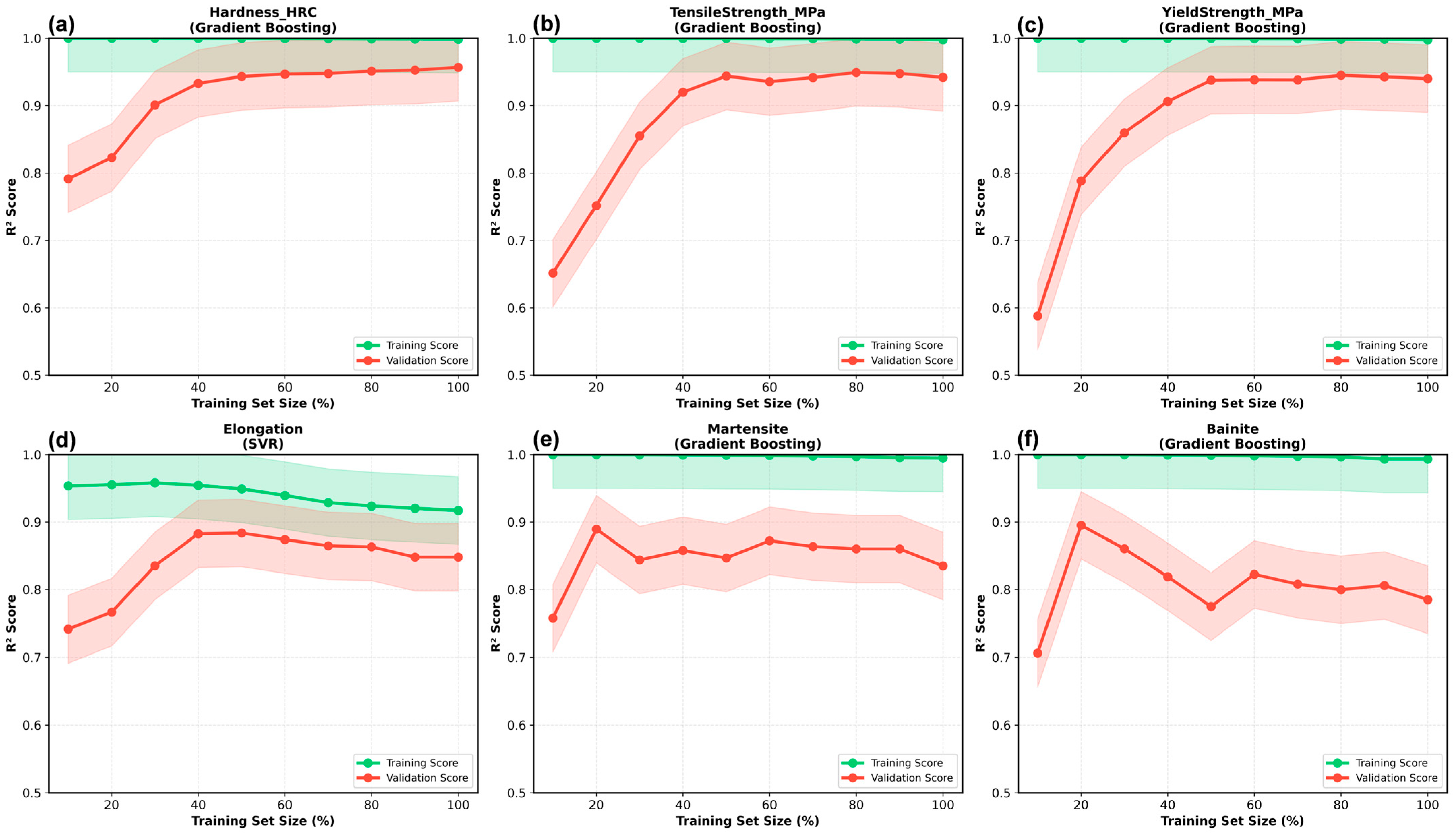

Physical consistency validation, which is rarely emphasized in ML studies, is essential for building trust in the results. The models satisfied monotonicity (hardness increases with carbon at fixed cooling, R2 = 0.97), appropriate limits (martensite > 95% for C > 0.3% at severe quench), and literature benchmarks (1.8% mean error versus ASM Handbook). Such validation transcends statistical metrics, detects dataset artifacts, and enables safer extrapolations. Future materials informatics should standardize the reporting of physical consistency, alongside R2 and RMSE. The learning curves reveal property-dependent data requirements. The hardness and strength properties plateaued at the 60% dataset (n ~ 144), suggesting 150–180 samples are sufficient for robust development and reducing the experimental burden by 40% compared to the full 400-sample program. The elongation and phase fractions showed non-converging curves, indicating the benefits of larger datasets (>400) or additional features capturing microstructural details (dislocation density and carbide morphology). These insights inform the experimental design of hybrid synthetic-experimental approaches. This study had some limitations. Phase transformation modeling uses simplified critical cooling rates to approximate complex TTT/CCT behavior. Although CALPHAD-based kinetic databases would improve accuracy, they require commercial licenses. A 400-sample synthetic dataset was generated using stratified random sampling to ensure equal representation across eight steel grades (50 samples each) and a balanced distribution across the cooling rate regimes and tempering categories. However, this intentional parameter decorrelation differs from industrial heat treatment datasets, where processing variables are often coupled through equipment constraints. For example, industrial furnaces may exhibit a correlation between the tempering temperature and time (higher temperatures are typically paired with shorter times for equivalent tempering parameters), or the cooling rate and quench temperature may couple in specific quenchant systems. Our synthetic approach intentionally varies the parameters independently to enable robust machine learning model training across the full parameter space. This design choice facilitates interpolation predictions but may reduce the direct transferability to facilities with strongly coupled parameters. For such applications, we recommend supplementing synthetic data with facility-specific experimental samples that capture the actual parameter coupling patterns. Property correlations assumed phase-weighted hardness without explicit modeling of dislocation density, carbide morphology, or retained austenite effects.

The current framework excludes microalloying elements (V, Nb, Ti) and trace impurities (S, P, N), which significantly affect modern commercial steels, particularly high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) grades and microalloyed steels. Vanadium and niobium form fine carbonitride precipitates that contribute 50–200 MPa additional strength through precipitation hardening mechanisms not captured by phase-weighted hardness correlations (Equation (4)). Sulfur and phosphorus affect grain boundary cohesion and impact toughness through segregation. This limitation restricts the direct applicability of the framework to plain carbon steels (1000 series, representing approximately 30% of steel production) and conventional low-alloy steels (4000 and 5000 series, representing approximately 25% of production), where strengthening arises primarily from solid solution and transformation hardening. The extension to HSLA and microalloyed grades requires the incorporation of precipitation strengthening models, which necessitates additional training data capturing precipitation kinetics across relevant tempering ranges [

41,

42]. Processing idealized uniform austenitizing and constant cooling rates; real components exhibit through-thickness gradients, requiring finite element thermal modeling integration. These limitations suggest that the current models are suitable for laboratory samples with controlled processing, and industrial component prediction must be coupled with process simulation software. The processing model assumes spatially uniform austenitizing and constant cooling rates throughout the component cross-section, which represents significant idealization compared to real industrial components. Large parts (>30 mm diameter) experience through-thickness thermal gradients during both heating and cooling: surface regions austenitize and quench faster than core regions, producing hardness gradients of 8–15 HRC between surface and center in 50–100 mm diameter cylinders. Our current framework cannot predict such gradients without integrating finite element heat transfer modeling to calculate local thermal histories as a function of position. This limitation restricts the direct applicability of the model to: (1) laboratory samples (<15 mm thickness) where thermal gradients are negligible, (2) induction-hardened components where only surface layer transformations matter, and (3) preliminary screening applications providing average property estimates. For industrial component prediction requiring through-thickness property distributions, we recommend coupling our ML models with commercial heat treatment simulation software (e.g., DANTE, SYSWELD) that provides location-specific thermal histories as inputs to property prediction models [

3,

43].

The applicability of the framework varies across steel categories based on their alignment with the theoretical assumptions. Direct applicability (predicted R

2 = 0.91–0.97) encompasses plain carbon steels (1000 series) and conventional low-alloy steels (4000 and 5000 series), representing ~55% of global production, where transformations follow Koistinen-Marburger-Grossmann kinetics (Equations (1)–(3)) and properties scale with phase-weighted hardness (Equation (4)) without significant precipitation hardening. Simple tool steels showed good applicability (estimated R

2 = 0.88–0.92) with minor extensions. Water-hardening (W1, W2) and oil-hardening (O1, O6) grades primarily form martensite plus retained austenite with properties predictable from carbon-hardness correlations. The required extensions are as follows: (1) retained austenite fraction estimation via Ms-temperature relationships and (2) adjusted tempering response for trace chromium/tungsten carbide resistance. Development effort: 1–2 weeks plus 50–80 supplementary samples. Complex tool steels show limited applicability (estimated R

2 = 0.65–0.78) requiring substantial extensions. High-carbon high-chromium grades (D2:1.5% C, 12% Cr with 10–20 vol% M7C3 carbides), hot-work steels (H13:0.4% C, 5% Cr, 1.5% Mo, 1% V), and high-speed steels (M2:0.85% C, 6% W, 5% Mo, 2% V, 4% Cr) violate three assumptions: (1) primary carbides occupy a significant volume not modeled in the four-phase system, (2) secondary carbide precipitation during tempering (Mo2C, V4C3 at 500–600 °C) contradicts the monotonic hardness-tempering relationship (Equation (5)), and (3) high total alloying (17–20% in M2, M4) exceeds the Grossmann validation range (<5%). Extensions require Kampmann-Wagner precipitation modeling, explicit carbide volume tracking, dispersion strengthening corrections, plus 200–300 additional samples. Development: 4–6 weeks. HSLA steels (X60-X80, DP590/780) show moderate applicability (R

2 = 0.70–0.80) requiring microalloying extensions. Vanadium, niobium, and titanium form fine precipitates (5–20 nm) contributing 50–200 MPa via Orowan strengthening, which is not captured by phase-weighted hardness. Controlled rolling produces refined grains that require Hall-Petch corrections. Without extensions, the yield strength is systematically underestimates by 8–20%. Development: 3–4 weeks plus 100–150 samples [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. Applicability hierarchy: Plain carbon + conventional alloy (55%, R

2 = 0.91–0.97, direct) > Simple tools (5%, R

2 = 0.88–0.92, minor extensions) > HSLA (30%, R

2 = 0.70–0.80, moderate) > Complex tools (10%, R

2 = 0.65–0.78, substantial extensions).

The optimal strategy combines synthetic and experimental data. Large synthetic datasets (300–400 samples) provide comprehensive parameter coverage at a minimal cost (

$500 computational time versus >

$50,000 experimental). Targeted experimental data (50–100 samples) validate critical conditions and capture phenomena that are difficult to model theoretically (e.g., grain boundary precipitation and texture). Transfer learning or Bayesian updating refines synthetic-trained models using experimental data, thereby leveraging the advantages of both approaches. Preliminary results using 80% synthetic + 20% experimental improved R

2 by 0.03–0.05 across properties. Industrial implementation requires addressing practical deployment. Models must be integrated with SCADA systems for real-time control, furnace software for automated recipe adjustments, and quality management systems for certification documentation. Uncertainty quantification through Bayesian neural networks or conformal prediction enables risk-based decisions by providing confidence intervals that meet specification tolerances rather than point predictions alone. Explainability via LIME or counterfactual analysis builds user trust by showing how to achieve the desired properties rather than the black-box outputs. Continuous learning frameworks enable model updates as facilities accumulate operational data, transforming static research artifacts into living systems that improve with experience. This methodology can be applied to other mature material systems. Aluminum alloys (age hardening via Shercliff–Ashby precipitation models [

29]), titanium alloys (α + β transformations via CCT behavior [

30]), and superalloys (γ’ precipitation kinetics [

31]) have theoretical foundations that enable synthetic data generation. Additive manufacturing processes couple rapid solidification models with thermal–mechanical simulations for process–structure–property prediction. Surface treatments (carburizing and nitriding) employ established diffusion models. Each system requires careful assessment of theoretical maturity and validation against experimental benchmarks before production.

This study has broader implications for materials informatics that emerge from this work. Success depends less on big data than on smart data utilization; well-constructed 400-sample synthetic datasets outperformed larger but noisier experimental compilations in preliminary comparisons. Theory-guided machine learning, which incorporates domain knowledge through synthetic data, physics-informed loss functions, or architecture design, improves performance, interpretability, and physical consistency compared to pure data-driven approaches, which risk spurious correlation learning. Validation requires physical consistency beyond cross-validation statistics, as models that achieve a high R

2 on flawed datasets may learn the artifacts. The claimed 40–60% experimental reduction represents a theoretical estimate based on learning curve analysis (

Figure 6) rather than empirical industrial validation. This estimate is derived from mechanical property convergence at approximately 60% of the full dataset (

n ≈ 150 vs. 400), suggesting that 240 samples suffice, where traditional full factorial designs might require 400. However, this calculation makes several assumptions that limit its direct industrial applicability: (1) it assumes that synthetic data accurately captures all relevant physics (validated only against literature benchmarks, not production data); (2) it assumes that the convergence patterns observed in our specific dataset generalize to other steel grades and processing conditions; (3) it does not account for regulatory or certification requirements that may mandate minimum experimental sample sizes regardless of computational predictions; and (4) it focuses on model training requirements rather than end-to-end development timelines, including experimental design, validation, and implementation phases. Rigorous validation of cost-reduction claims requires prospective industrial case studies comparing traditional experimental campaigns with hybrid synthetic-experimental approaches for identical objectives (e.g., developing heat treatment specifications for new component designs), measuring the total samples required, timeline duration, and costs while ensuring equivalent specification reliability. Such validation would establish confidence bounds for the claimed reductions across different industrial contexts (automotive, aerospace, and tooling) and identify scenarios in which synthetic approaches provide maximum versus minimal benefits. Without such empirical validation, the 40–60% figure should be interpreted as a theoretical potential requiring case-by-case confirmation rather than a guaranteed outcome. We recommend that industrial partners pursuing implementation conduct pilot validation studies before committing to production-scale adoption based solely on these computational estimates. Synthetic data approaches democratize ML, enabling smaller groups lacking extensive experimental infrastructure to leverage advanced methods for developing ML models. The current gradient boosting implementation provides deterministic point predictions (e.g., “predicted hardness = 45.2 HRC”) without associated uncertainty estimates, limiting risk-aware industrial decision-making. Incorporating probabilistic prediction methods would enable quantified confidence intervals to support specification compliance assessment. For example, prediction intervals (e.g., “hardness = 45.2 ± 4.6 HRC, 95% confidence”) allow the calculation of the probability of meeting specifications (e.g., P[hardness ≥ 40 HRC] = 97.3%), which is particularly valuable for high-consequence applications (aerospace, medical devices) where conservative process design ensures high conformance probability despite prediction uncertainty. Implementation approaches include (1) quantile regression forests generating prediction intervals from tree ensemble distributions, (2) Bayesian gradient boosting providing posterior distributions over predictions, and (3) conformal prediction constructing distribution-free confidence regions from calibration data. Such extensions represent important directions for production-ready implementations, where engineers require not only predicted values but also confidence in those predictions relative to specification tolerances [

44,

45]. The current gradient boosting implementation provides deterministic point predictions (e.g., “predicted hardness = 45.2 HRC”) without associated uncertainty estimates, limiting risk-aware industrial decision-making. Incorporating probabilistic prediction methods would enable quantified confidence intervals to support specification compliance assessment. For example, prediction intervals (e.g., “hardness = 45.2 ± 4.6 HRC, 95% confidence”) allow the calculation of the probability of meeting specifications (e.g., P[hardness ≥ 40 HRC] = 97.3%), which is particularly valuable for high-consequence applications (aerospace, medical devices) where conservative process design ensures high conformance probability despite prediction uncertainty. Implementation approaches include (1) quantile regression forests generating prediction intervals from tree ensemble distributions, (2) Bayesian gradient boosting providing posterior distributions over predictions, and (3) conformal prediction constructing distribution-free confidence regions from calibration data. Such extensions represent important directions for production-ready implementations, where engineers require not only predicted values but also confidence in those predictions relative to specification tolerances [

44,

45]. Optimal material design combines human expertise (problem formulation, assumption validation, and failure analysis) with AI capabilities (pattern recognition, high-dimensional optimization, and exhaustive search) through hybrid workflows that maximize synergy.

Future development should pursue the following four directions. First, experimental validation integration: collect 50–100 targeted samples capturing rare scenarios (cryogenic treatment, austempering, and multiple tempering), refine models via transfer learning preliminary trials suggest R2 improvements of 0.03–0.05. Second, uncertainty quantification using Bayesian gradient boosting or conformal prediction provides confidence intervals (e.g., “hardness = 45.2 ± 4.6 HRC, 95% confidence”) enabling risk-based decisions for aerospace/medical applications. Third, physics-informed neural networks incorporating transformation kinetics through specialized loss functions penalizing metallurgical constraint violations are expected to reduce data requirements by 30–40%. Fourth, industrial deployment pilots with continuous learning: integrate models with SCADA systems for real-time control, implement automated furnace recipe adjustment, and enable model updates from accumulating production data, transforming static artifacts into living systems. Initial pilots should target automotive facilities processing 10,000–50,000 parts monthly, providing validation datasets and user feedback for iterative refinement.