Property Optimization of Al-5Si-Series Welding Wire via La-Ce-Ti Rare-Earth Microalloying

Abstract

1. Introduction

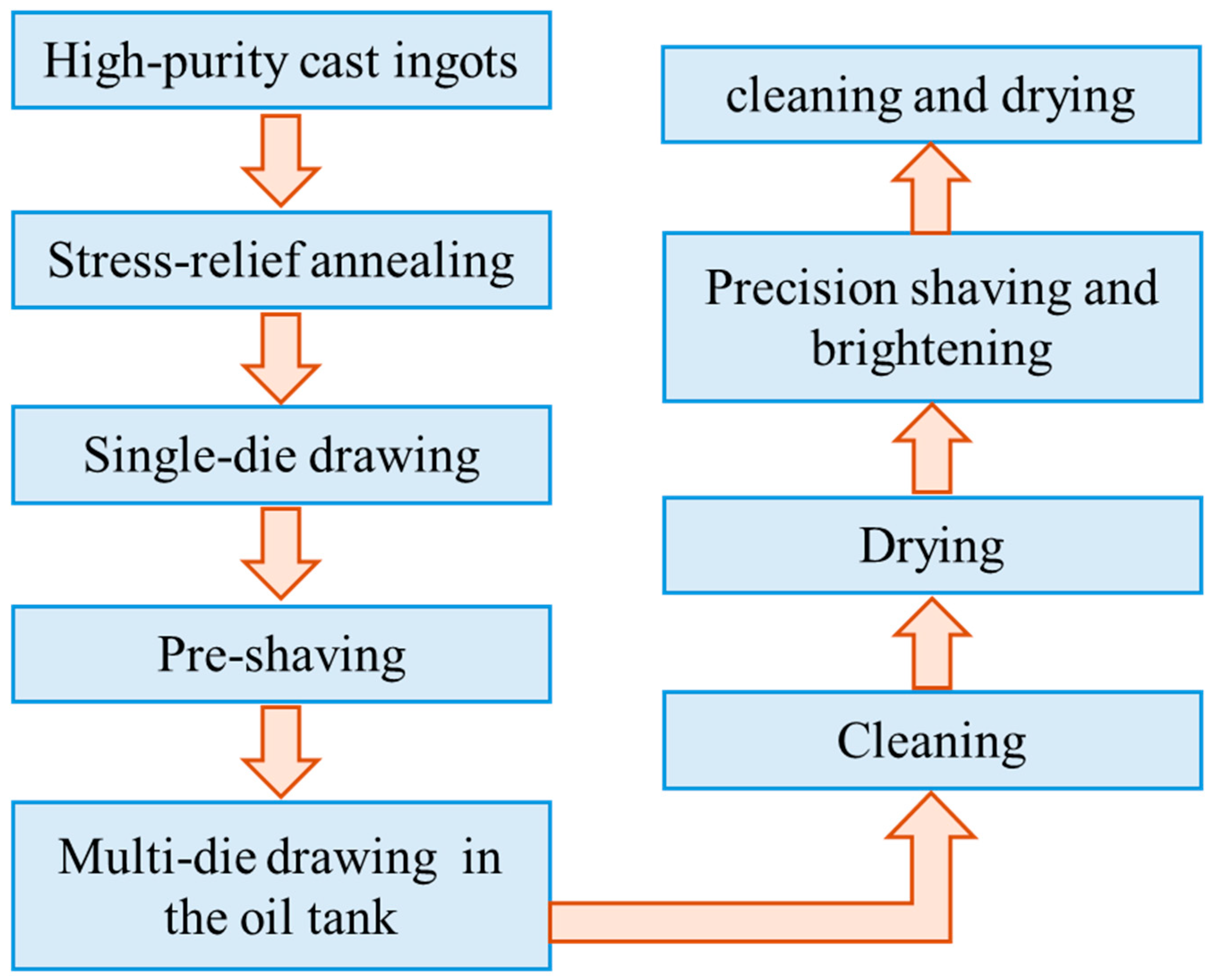

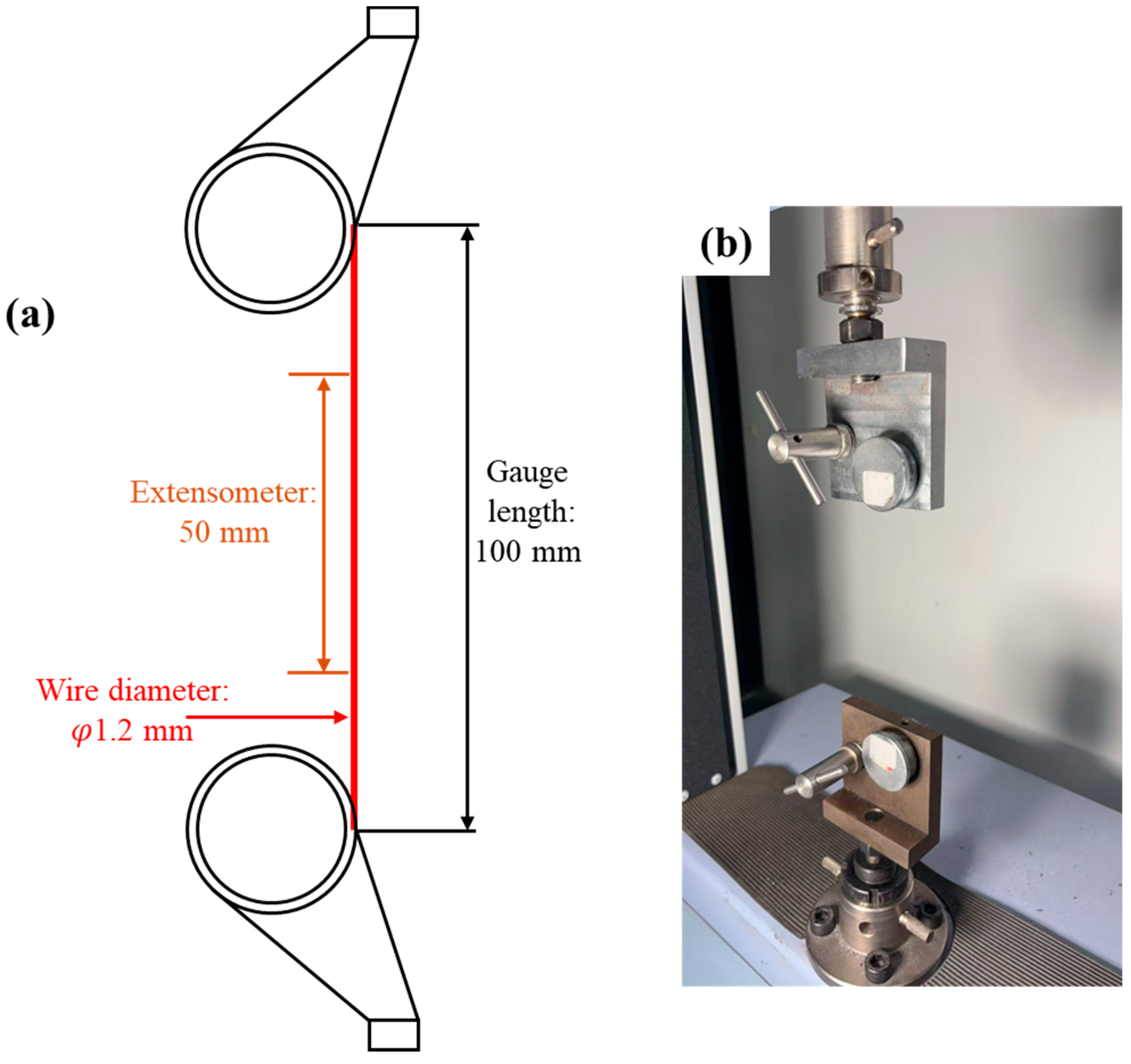

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

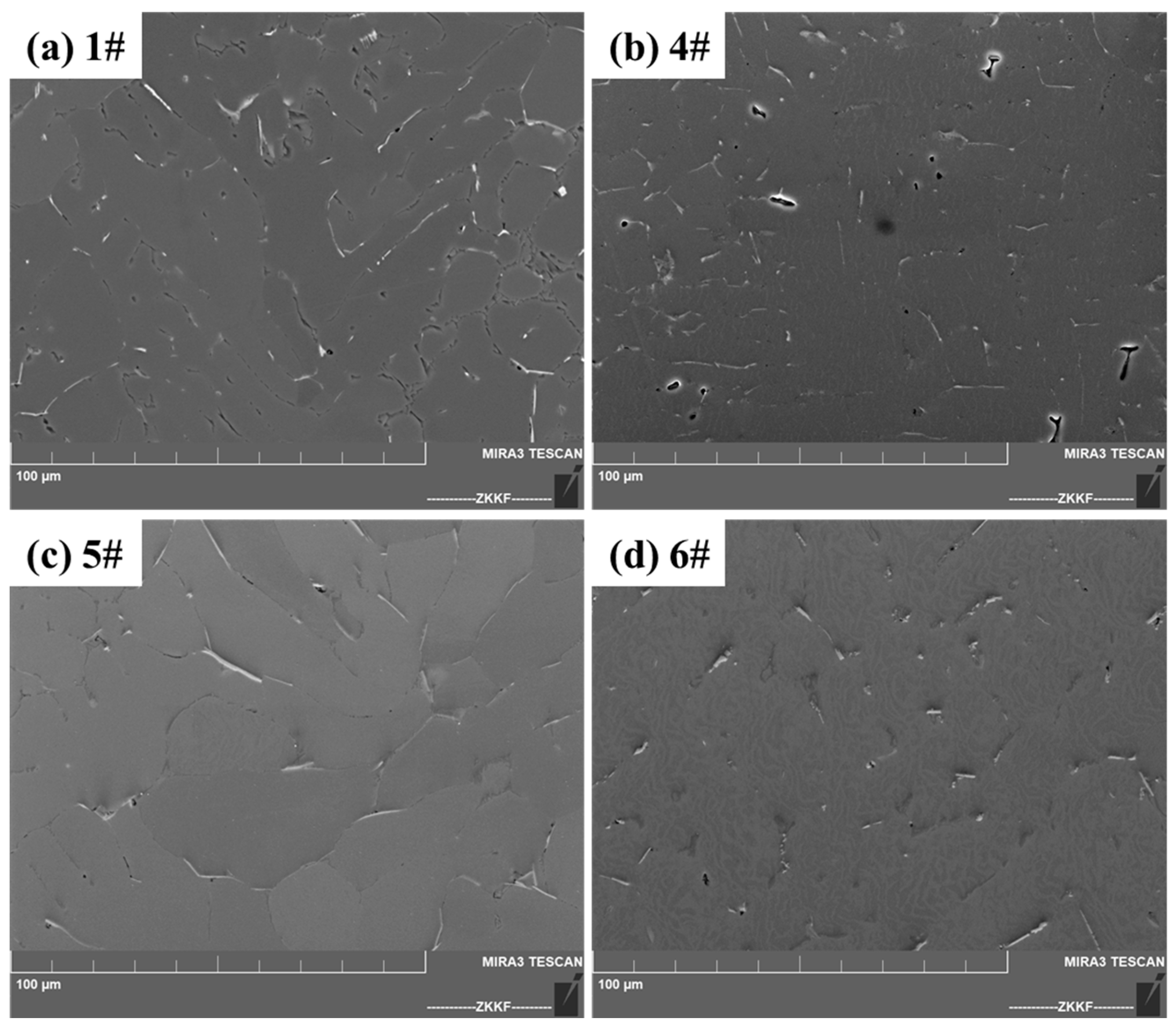

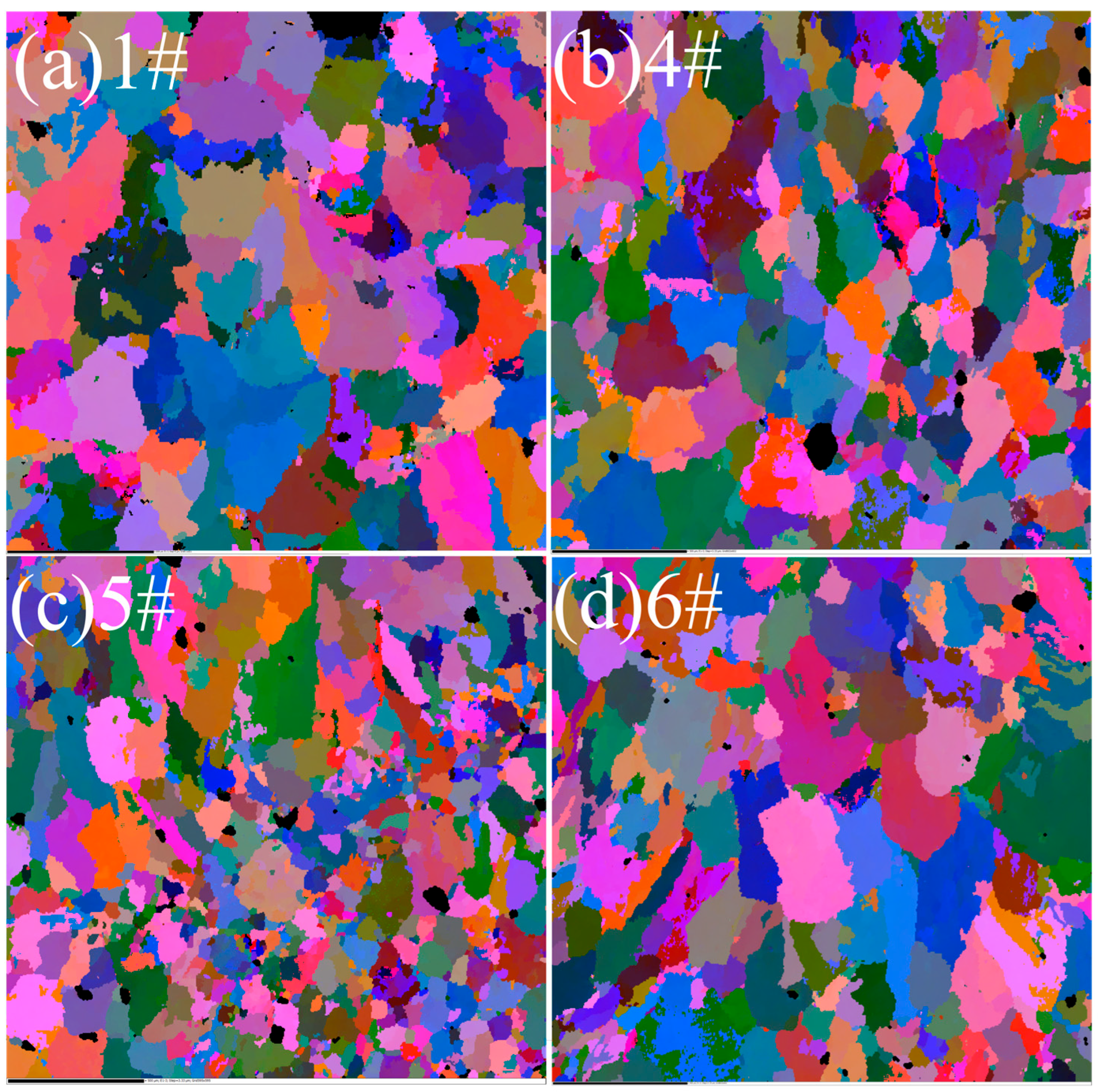

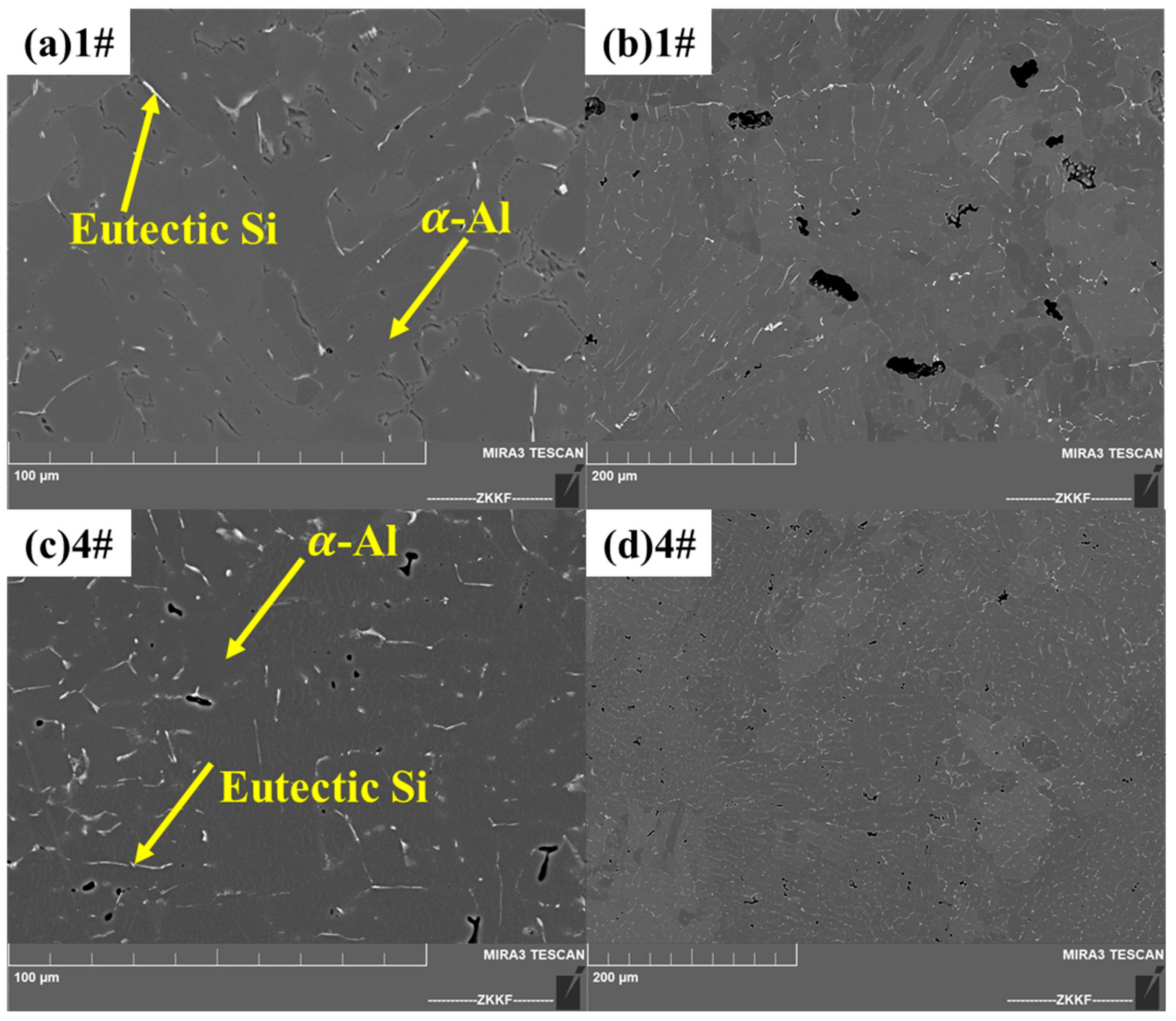

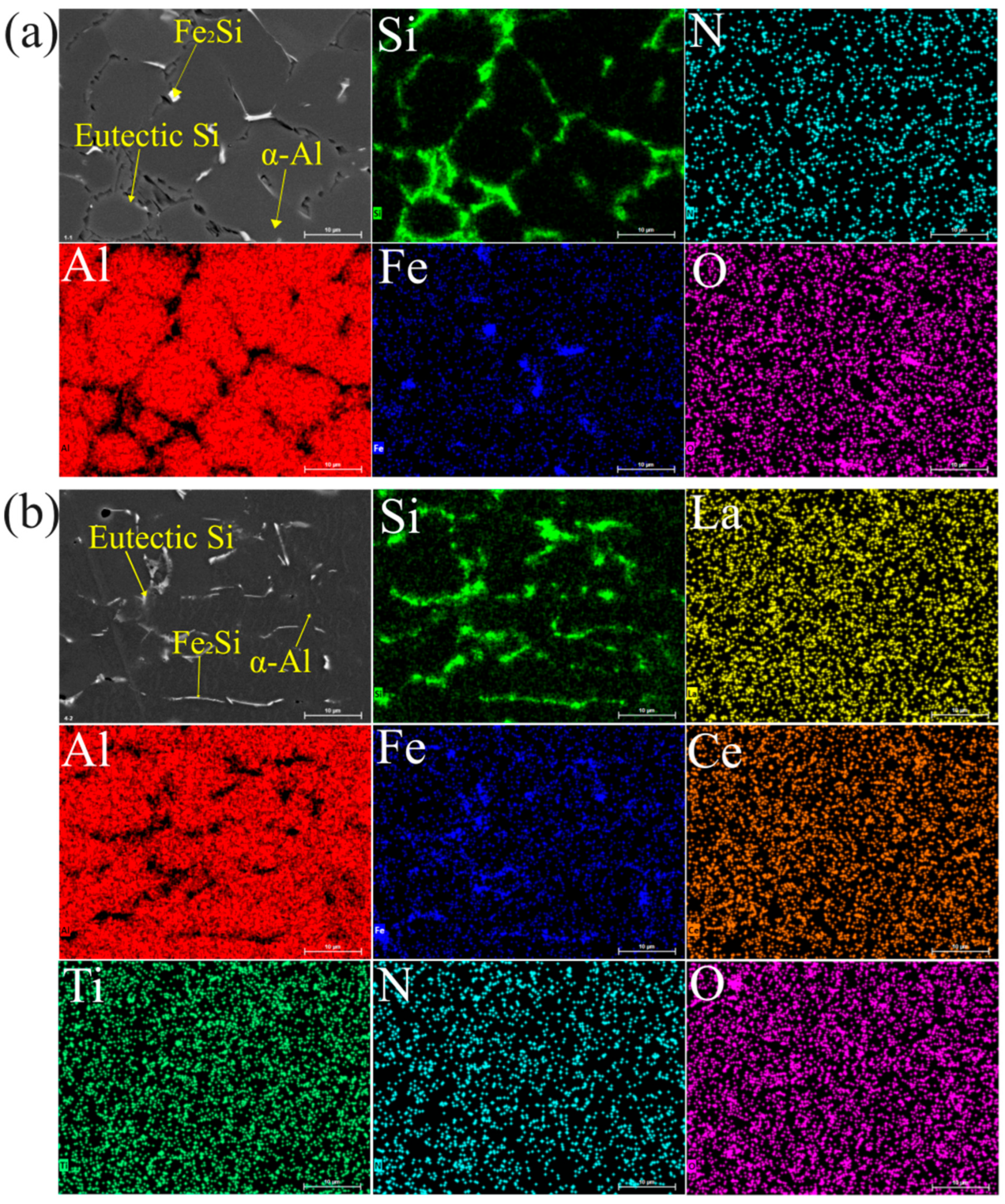

3.1. Microstructure Evolution

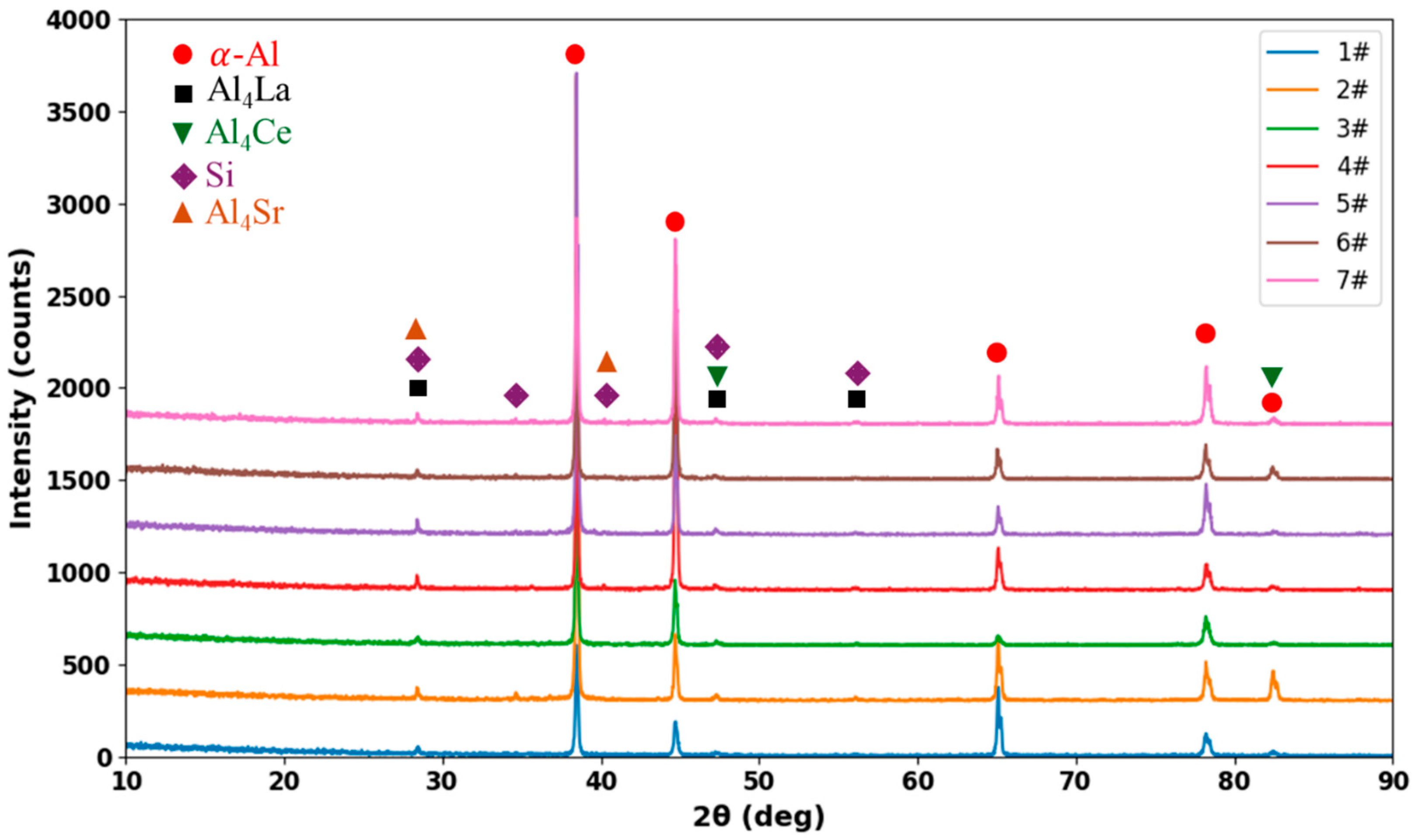

3.2. Phase Distribution

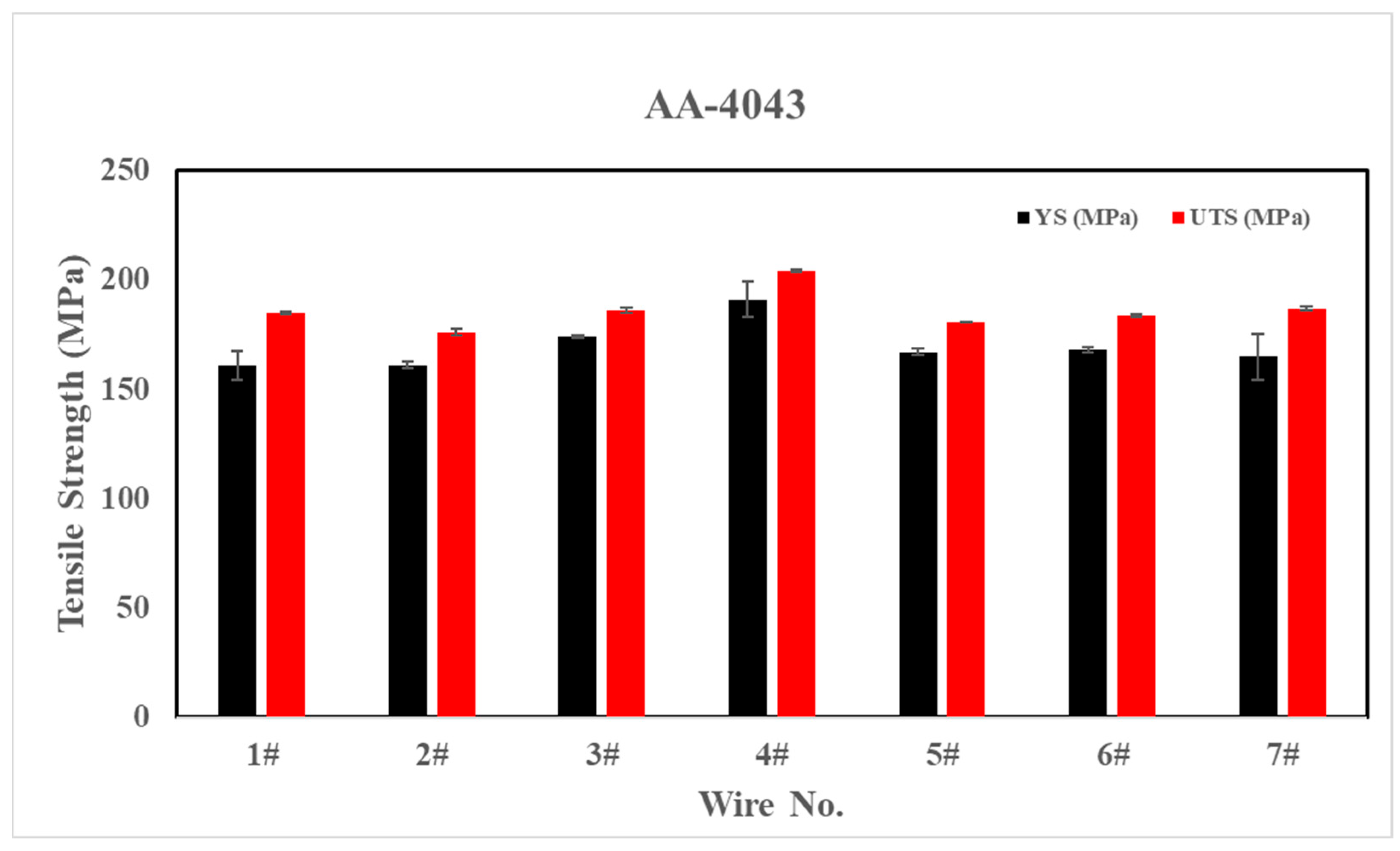

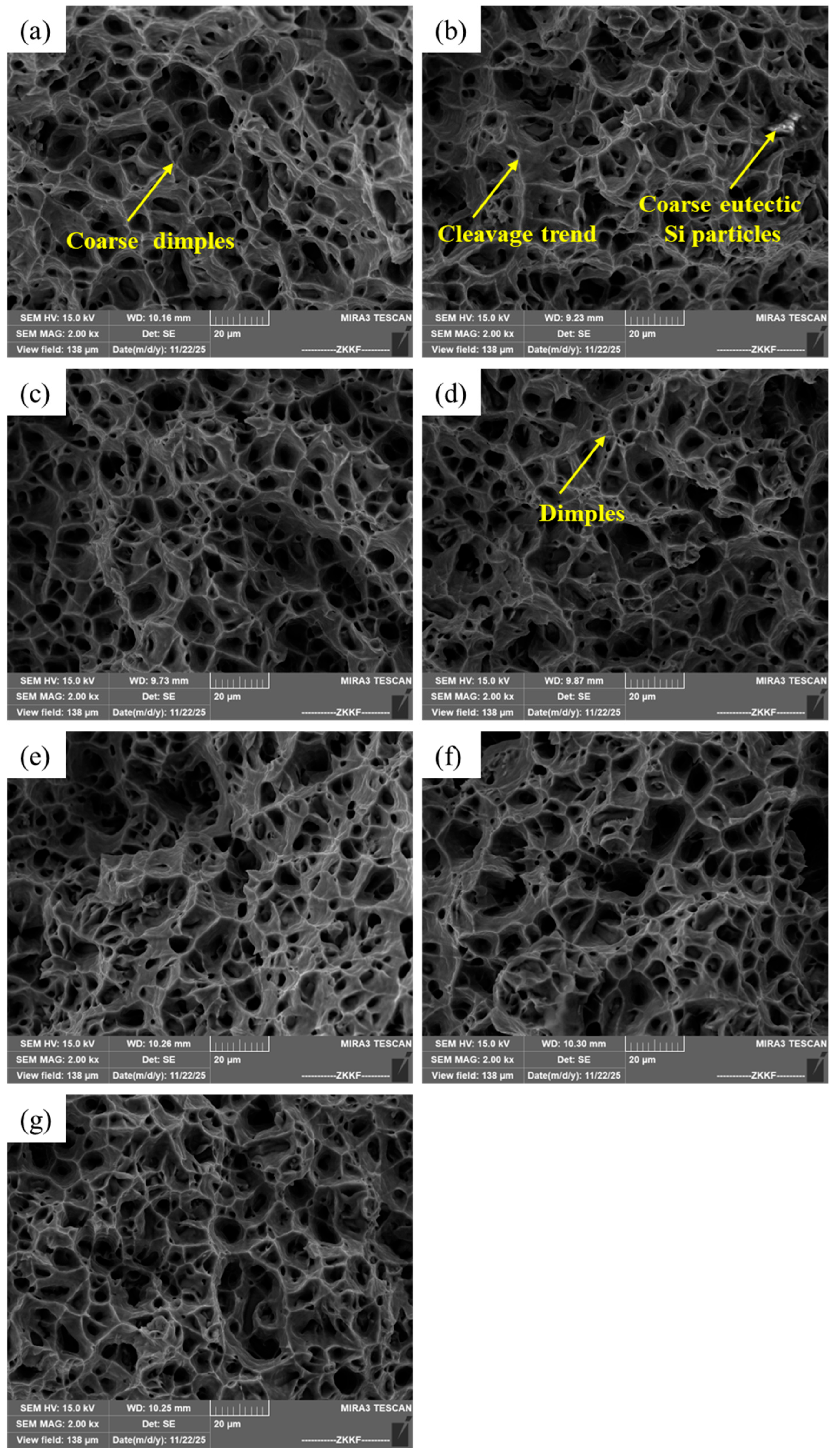

3.3. Mechanical Properties and Fracture Analysis

4. Conclusions

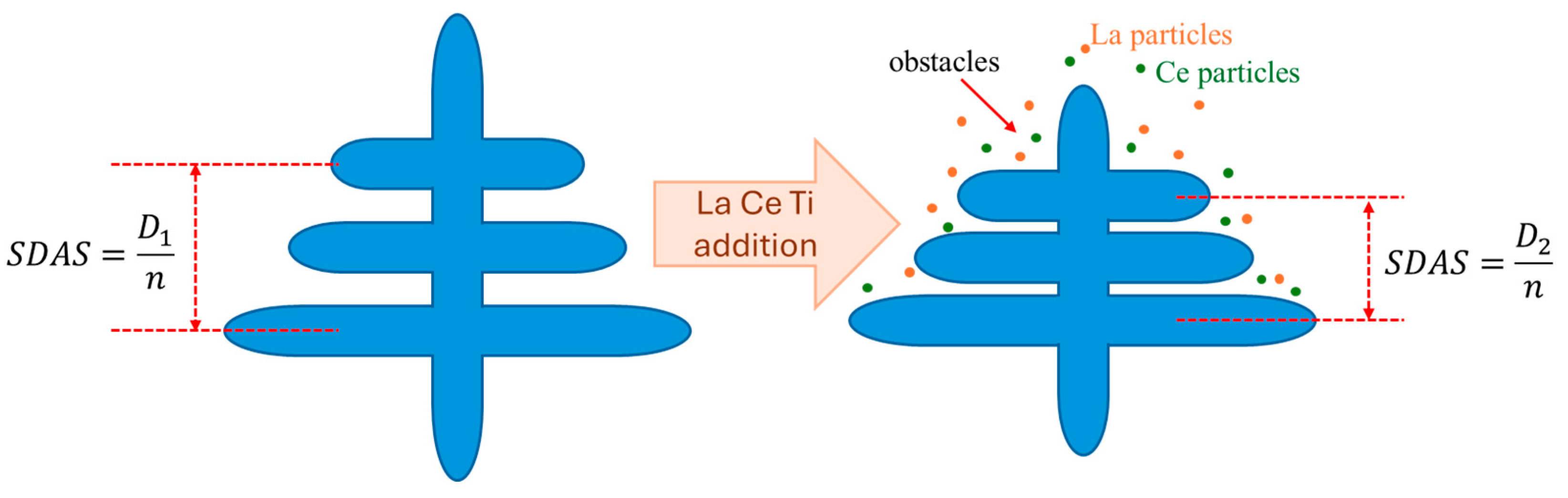

- The incorporation of RE elements (La, Ce) significantly refined the -Al dendrites and eutectic Si phase and reduced the secondary dendrite arm spacing (SDAS). The eutectic Si phase morphology transformed from coarse rod-like and acicular-like structures into fine, fibrous-like forms, effectively reducing stress concentration sites and suppressing microvoid nucleation.

- These microstructural improvements led to measurable mechanical enhancements. The yield strength and ultimate tensile strength increased from 161 MPa to 191 MPa and 185 MPa to 204 MPa, corresponding to 18.6% and 10.3% increases, respectively. In addition, the strength mismatch between the welding wire and the AA6061-T6 base metal decreased by 6.5–12.5%, contributing to improved weldability and enhanced joint strength.

- Furthermore, the minor addition of 0.019Ti-0Sr-0.02La-0.03Ce not only refined the fusion zone microstructure but also significantly reduced weld porosity. This demonstrates that microalloying provides an effective pathway to simultaneously improve weld microstructure, mechanical performance, and weldability. The findings of this work not only offer guidance for designing improved filler wires but also present a promising approach for enhancing material quality in additive manufacturing applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Y.C.; Dong, B.X.; Yang, H.Y.; Yao, X.Y.; Shu, S.L.; Kang, J.; Meng, J.; Luo, C.J.; Wang, C.G.; Gao, K.; et al. Research progress, application and development of high performance 6000 series aluminum alloys for new energy vehicles. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 32, 1868–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Dong, Q.; Fu, Y.N.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, B.D. Effect of addition of La and Ce on solidification behavior of Al-Cu alloys. Mater. Lett. 2022, 324, 132653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.F.; Du, Z.X.; Gong, T.H.; Wang, W.Y.; Pan, Z.R.; Qi, L.L.; Sun, B.A.; Liu, J.S. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Ce-La mixed rare earths modified Al-Mg-Si alloy under cold rolling and heat treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1021, 179773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Zhang, Q.X.; Ma, Y.W.; Xu, Y.; Han, X.H.; Li, Y.B. A comparative study on mechanical performance of traditional and magnetically assisted resistance spot welds of A7N01 aluminum alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 66, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinenko, A.; Zuiko, I.; Malopheyev, S.; Mironov, S.; Kaibyshev, R. Dissimilar friction-stir welding of aluminum alloys 2519, 6061, and 7050 using an additively-manufactured tool. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 156, 107851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Ge, F.B.; Wu, S.Y.; Tan, H.J.; Hu, Z.G. Effect of La-Ce additions on microstructure and mechanical properties of cast Al-3Si-0.5Cu-0.7Fe alloy with high thermal conductivity. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1024, 180249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.C.; Lu, L.Z.; Li, G.J.; Huang, Y.L.; Yang, L.L.; Guo, H.T.; Wu, F. Influence of minor addition of La and Ce on the ageing precipitation behavior of Sr-modified Al-7Si-0.6Mg alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 108825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.S.; Ouyang, Z.P.; Jin, H.X.; Kong, Y.J.; Wei, Y.H. Study on oscillating laser welding of 6061-T6 aluminum alloy medium-thick plate: Energy distribution, joint forming, texture evolution, and mechanical properties. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 188, 112910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.X.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Meng, Y.F.; Deng, A.L.; Wu, X. Study on the influence of Al-Si welding wire on porosity sensitivity in laser welding and process optimization. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 170, 110261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xue, S.B.; Ma, C.L.; Han, Y.L.; Lin, Z.Q. Effect of combinative addition of Ti and Sr on modification of AA4043 welding wire and mechanical properties of AA6082 welded by TIG welding. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2017, 27, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.D.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.X.; Jiang, C.L.; Huang, H.F. Effect of La and Ce alloying on microstructure and the thermal deformation mechanism of commercial Al-Mg-Si alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 1613–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Pan, S.; Liao, G.Z.; Ali, A.; Wang, S.B. Sc-containing hierarchical phase structures to improve the mechanical and corrosion resistant properties of Al-Mg-Si alloy. Mater. Des. 2022, 218, 110699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghayeghi, R.; Timelli, G. An investigation on primary Si refinement by Sr and Sb additions in a hypereutectic Al-Si alloy. Mater. Lett. 2021, 283, 128779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, V.; Ravi, M.; Prabhu, K.N. Effect of Ni and Sr additions on the microstructure, mechanical properties, and coefficient of thermal expansion of Al-23%Si alloy. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 2732–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, H.M.; Jiang, X.Q.; Qiao, N.; Liu, X.K. Effects of Er/Sr/Cu additions on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Mg alloy during hot extrusion. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 708, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Bu, F.Q.; Zheng, T.; Meng, F.Z.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, D.P.; Qiu, X.; Meng, J. Influence of trace Sr additions on the microstructures and the mechanical properties of Mg–Al–La-based alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 619, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.G.; Mosleh, A.O.; Mohamed, M.S.; El-Moayed, M.H.; Khalifa, W.; Pozdniakov, A.V.; Salem, S. The impact of Ce-containing precipitates on the solidification behavior, microstructure, and mechanical properties of Al-6063. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 948, 169805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.J.; Wu, J.; Jiang, H.X.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhao, J.Z.; He, J. Effect of micro-alloying element La on corrosion behavior of Al-Mg-Si alloys. Corros. Sci. 2021, 179, 109113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.J.; Zhang, L.L.; Jiang, H.X.; Zhao, J.Z.; He, J. Effect mechanisms of micro-alloying element La on microstructure and mechanical properties of hypoeutectic Al-Si alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 47, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.H.; Zhou, H.P.; Kang, Y.P. The influence of rare earth elements on microstructures and properties of 6061 aluminum alloy vacuum-brazed joints. J. Alloys Compd. 2003, 352, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Q.; Cai, S.L.; Gu, J.; Liu, S.C.; Si, J.J. Co-doping of La/Ce and La/Er induced precipitation strengthening for designing high strength Al-Mg-Si electrical conductive alloys. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.X.; Li, S.X.; Zheng, Q.J.; Zhang, L.L.; He, J.; Song, Y.; Deng, C.K.; Zhao, J.Z. Effect of minor lanthanum on the microstructures, tensile and electrical properties of Al-Fe alloys. Mater. Des. 2020, 19, 108991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandee, P.; Gourlay, C.M.; Belyakov, S.A.; Patakham, U.; Zeng, G.; Limmaneevichitr, C. AlSi2Sc2 intermetallic formation in Al-7Si-0.3Mg-xSc alloys and their effects on as-cast properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 731, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgallad, E.M.; Doty, H.W.; Alkahtani, S.A.; Samuel, F.H. Effects of La and Ce Addition on the Modification of Al-Si Based Alloys. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 5928, 5027243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acherjee, B. Hybrid laser arc welding: State-of-art review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 99, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, D.G.; Wang, D.F.; Ma, B.; Ma, L.C.; Xin, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Dai, Y. Research on Laser-MIG Composite Welding of TC4 Titanium Alloy. Ordnance Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 42, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM E8/E8M-13a; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.C.; Zhang, M.; Feng, Q.S.; Zhang, D.; Gao, P.Y.; Li, C.H. The Influence of the Combined Addition of La–Ce Mixed Rare Earths and Sr on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AlSi10MnMg Alloy. Metals 2024, 14, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Y.; Zhang, H.R.; Jiang, H.T.; Mi, Z.L.; Zhang, H. Multi-Refinement Effect of Rare Earth Lanthanum on α-Al and Eutectic Si Phase in Hypoeutectic Al-7Si Alloy. Metals 2020, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinifar, M.; Malakhov, D.V. The Sequence of Intermetallics Formation during the Solidification of an Al-Mg-Si Alloy Containing La. Met. Mater. Trans. A 2010, 42, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.M.; Fan, Z.T.; Dai, Y.C.; Li, C. Effects of rare earth elements addition on microstructures, tensile properties and fractography of A357 alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 597, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | Al | Si | Fe | Ti | Sr | La | Ce | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alloy Number | ||||||||

| 1# | Rem 1 | 5.14 | 0.16 | \ | \ | \ | \ | |

| 2# | Rem | 5.19 | 0.17 | 0.017 | \ | \ | \ | |

| 3# | Rem | 5.17 | 0.17 | 0.018 | 0.01 | \ | \ | |

| 4# | Rem | 5.09 | 0.16 | 0.019 | \ | 0.02 | 0.03 | |

| 5# | Rem | 5.10 | 0.16 | 0.020 | \ | \ | 0.05 | |

| 6# | Rem | 5.08 | 0.16 | 0.020 | \ | 0.05 | \ | |

| 7# | Rem | 5.11 | 0.17 | \ | 0.02 | \ | \ | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Jiang, T.; Ma, B.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, W.; Chen, D.; Zhang, L. Property Optimization of Al-5Si-Series Welding Wire via La-Ce-Ti Rare-Earth Microalloying. Crystals 2026, 16, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010006

Yang Y, Wang D, Jiang T, Ma B, Dong Z, Zhang W, Chen D, Zhang L. Property Optimization of Al-5Si-Series Welding Wire via La-Ce-Ti Rare-Earth Microalloying. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yi, Dafeng Wang, Tong Jiang, Bing Ma, Zhihai Dong, Wenzhi Zhang, Donggao Chen, and Long Zhang. 2026. "Property Optimization of Al-5Si-Series Welding Wire via La-Ce-Ti Rare-Earth Microalloying" Crystals 16, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010006

APA StyleYang, Y., Wang, D., Jiang, T., Ma, B., Dong, Z., Zhang, W., Chen, D., & Zhang, L. (2026). Property Optimization of Al-5Si-Series Welding Wire via La-Ce-Ti Rare-Earth Microalloying. Crystals, 16(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010006