The Quest for Low Work Function Materials: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

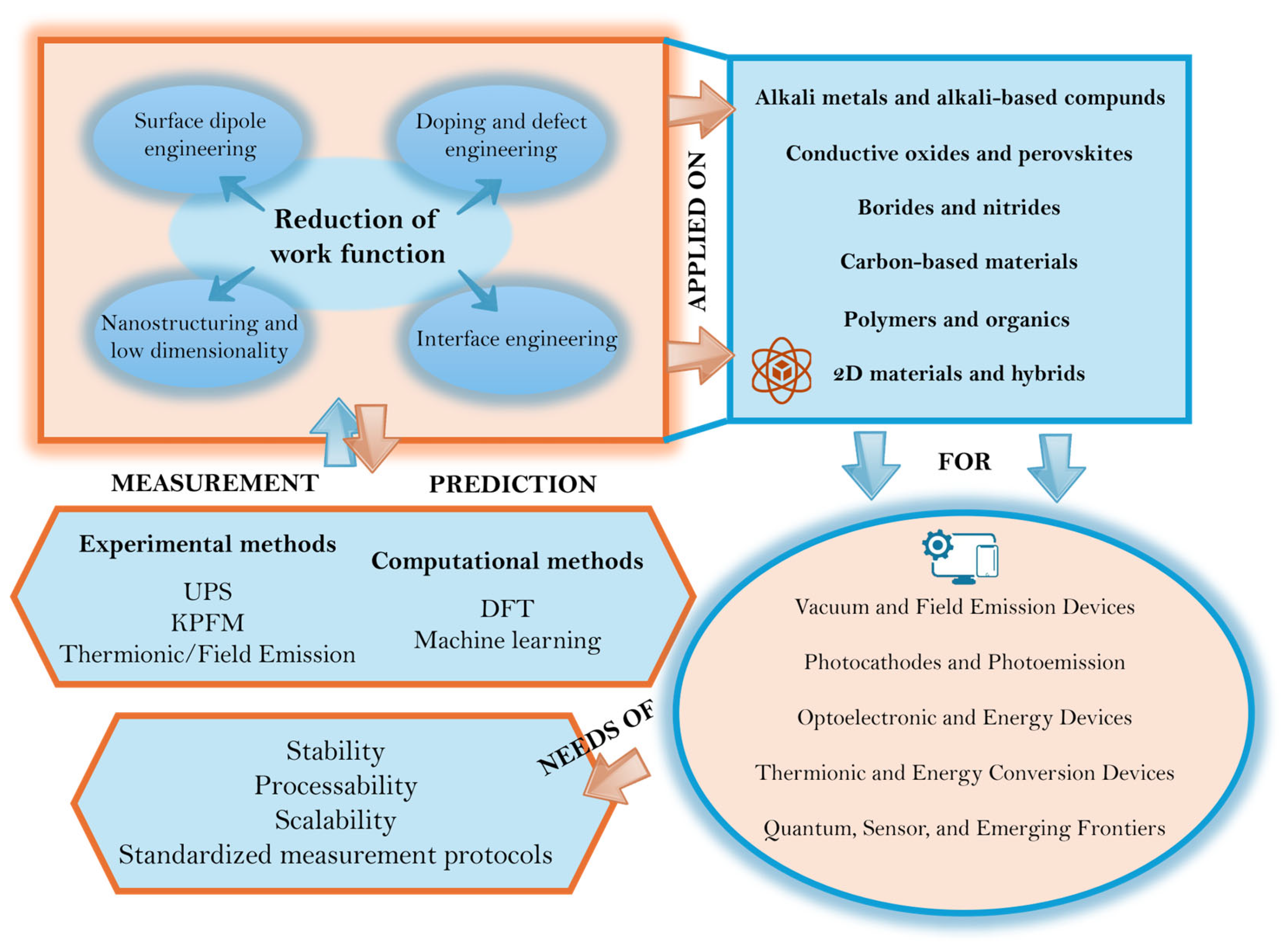

2. Theoretical Foundations and Mechanisms

- Surface dipoles and adsorbates: At the material surface or interface, a dipole layer (for example, due to adsorbed alkali metals, molecules, or an atomically thin coating) shifts the vacuum surface potential, thereby lowering (or raising) WF [24,25]. Carefully engineered surface dipoles can reduce WF down to 2–3 eV.

- Band structure and Fermi level tuning [26]: Materials with high carrier concentration (metallic conduction) and Fermi level close to the conduction band minimum (CBM) naturally exhibit lower WF. In oxides/perovskites, materials with barely filled d-bands tend to show lower WF values. For example, a density-functional theory (DFT) screening of perovskite oxides found that those with barely filled d-bands and AO-terminated surfaces achieved predicted WF ~0.9–1.5 eV [18].

- Surface termination, morphology, and defects: Crystallographic termination [27], surface relaxation/contamination and reconstruction, atomic steps and facets, roughness [28,29], as well as defect density and adsorbates, influence both local potential and electronic states at the surface, altering WF [30,31,32].

- Dimensional confinement and nanostructuring: For two-dimensional (2D) materials and nanostructures, quantum confinement, altered screening, and increased surface-to-volume ratio can reduce WF with respect to bulk values. Alkali-metal-adsorbed transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) were predicted to reach WF < 1 eV under idealized conditions [33]. In particular, geometry-induced quantum effects arising from surface nanostructuring provide an additional, fundamentally distinct route to WF and Fermi-level engineering. Periodic nanoscale features—such as nanogratings, nanopillars, and corrugated surfaces—can modify the electronic density of states through quantum confinement and boundary-condition effects, leading to an effective redistribution of carriers and a shift in the Fermi level, a mechanism often referred to as geometry-induced doping (G-doping) [34]. Unlike conventional chemical doping, G-doping does not rely on impurity incorporation but instead originates from the spatial modulation of the electronic wavefunctions imposed by nanoscale geometry (Figure 3) [35]. These effects can be coupled with enhanced sensitivity to adsorbates and surface dipoles, amplifying WF tuning compared to bulk counterparts. As a result, quantum confinement acts as a synergistic mechanism that complements dipole engineering and Fermi-level tuning in the design of LWF nanomaterials [36], which is of particular interest in nanostructured and vacuum microelectronic devices.

3. Strategies for Lowering the WF

3.1. Surface Dipole Engineering

3.2. Doping and Defect Engineering

3.3. Nanostructuring and Dimensional Control

3.4. Interface and Heterostructure Engineering

3.5. Synergistic Combinations and Trade-Offs

4. Families of LWF Materials

4.1. Alkali Metals and Alkali-Based Compounds

4.2. Borides and Nitrides

4.3. Barium- and Scandium-Based Oxides

4.4. Conductive Oxides, Perovskites, Polymeric and Organic/Hybrid Electrodes

4.5. Carbon-Based Materials

4.6. Two-Dimensional Materials and Hybrids

| Material | Work Function (eV) | Uncertainty | Theoretical/Experimental | Method/Experimental Details/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-adsorbed WTe2 (2D) | 0.7 | Theoretical [33] | ||

| Cs/O2 on n-GaAs | 0.7 | 0.1 eV | Experimental [73] | Photoemission low-energy cutoff (LEC), UHV under illumination (SPV). WF = 1.06 ± 0.1 eV, if not illuminated. |

| P-doped H-diamond/Si | 0.9 | N/A | Experimental [66] | Thermionic method (UHV, 650–1000 K) |

| BaZr0.375Ta0.5Fe0.125O3 | 0.93 | Theoretical [74] | AO-terminated | |

| BaMoO3 | 1.06 | Theoretical [74] | AO-terminated | |

| Ba0.25Sc0.25O on W (001) | 1.16 | Theoretical [75] | ||

| Cs/O on graphene | 1.25 | 0.08 eV | Experimental [41] | Photoemission low-energy cutoff (LEC). WF = 1.32 eV measured with KFPM at ambient conditions. If back-gated, WF decreases to 1.01 ± 0.05 eV. |

| N-doped H-diamond/Re | 1.34 | N/A | Experimental [76] | Thermionic method (UHV, 525–750 K) |

| CsScCl3 | 1.42 | Theoretical [17] | Termination: (100)-Sc, (100)-Cs-Cl | |

| SrN2 | 1.59 | Theoretical [17] | Termination: (110)-Sr | |

| BaSi2 | 1.68 | Theoretical [17] | Termination: (100)-Ba, (100)-Si | |

| CsI/W (110) | 1.69 | Theoretical [77] | ||

| La2O3−x (hexagonal) | 1.8 | Theoretical [78] | ||

| K-Cs-Rb | ≈1.8 | < 1% | Experimental [49] | Fowler photoelectric method, UHV, 90–450 K |

| La0.25Ba0.75B6 (001) | 1.84 | Theoretical [52] | ||

| Ba0.5O/Hf (1012) | 1.88 | Theoretical [56] | ||

| SrMoO3 | 1.93 | Theoretical [74] | AO-terminated | |

| BaF2/GaAs | 2.1 | N/A | Experimental [79] | UPS (UHV, cutoff energy by applying a series of negative bias voltages) |

| HfN (001) | 2.16 | Theoretical [52] | ||

| Ca/ZnO (001) | 2.25 | Theoretical [80] | ||

| SrVO3 (polycrystalline) | ≈2.3 | 0.1 eV | Experimental [81] | Thermionic method (800–1400 °C) |

| h-BN/LaB6 | 2.35 | N/A | Experimental [23] | Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (UHV, 77 K) |

| Mo2C(NH)2 | 2.4 | Theoretical [72] | NH-terminated | |

| p-Pyrrd–Phen on ITO/ZnO | 2.43 | N/A | Experimental [82] | UPS (UHV) |

| Ce0.25La0.75B6 (single-crystal, 001 termination) | 2.61 | N/A | Experimental [21] | Field-assisted thermionic emission (UHV, 1673–1873 K) |

5. Measurement and Computational Techniques

- Experimental methods: UPS can measure the difference between the vacuum level and the Fermi energy by analyzing the cut-off of emitted photoelectrons under ultraviolet excitation [83]. However, Helander et al. note important pitfalls [84], in that UPS typically measures the minimum WF (i.e., the lowest WF patch on an inhomogeneous surface) rather than an average, and measurement geometry (sample-detector alignment) and contamination critically influence the result. KPFM methods measure contact potential difference between a reference tip and the sample surface, enabling the mapping of WF variation across surfaces and operation in ambient or controlled atmospheres [85]. Nonetheless, tip WF drift, surface contamination, and stray fields must be carefully calibrated. Recently, an in-depth treatment of measurement artifacts, patch fields, and electric-field effects on measured WF values has been reported [37]. Field/thermionic emission experiments infer an effective WF from the temperature- or field-dependent emission current [86]; these methods reflect device-level performance but are influenced by surface morphology, local fields, and non-idealities. Based on these considerations, it is important to make a note regarding the experimental methods. Figure 7 provides a representative example of best practices in UPS-based WF measurements on semiconducting oxides. In particular, the application of a controlled bias voltage during cutoff acquisition minimizes spurious zero-field effects and charging-related distortions, enabling a more reliable determination of the equilibrium work function. This approach is consistent with established methodologies developed to mitigate measurement artifacts in complex semiconductor and dielectric stacks, as discussed in detail in the work of Martinez et al. [87]. Finally, it is important to underline that, when comparing reported WF values, best practices should include clearly specifying surface preparation, measurement environment (ultra-high vacuum vs. ambient), temperature, and uncertainty, as well as distinguishing between equilibrium WF and effective WF or illumination-assisted emission barriers. Such reporting is essential to ensure meaningful comparison across materials and techniques.

- Computational methods: DFT slab calculations model surface terminations and compute the potential drop from the slab Fermi level to the vacuum region, yielding theoretical WF [88]. Screening studies correlate bulk descriptors (e.g., d-band filling, oxygen p-band center) with predicted low WF values. A recent review summarizes workflows, errors, and correlation to the experiment [89]. A key challenge is modeling realistic surfaces: adsorbates, surface reconstructions, contamination, finite temperature effects, and polycrystalline facets often shift WF with respect to ideal slabs. In recent years, machine learning (ML) and data-driven computational approaches have increasingly complemented traditional DFT calculations in the study of WF and materials engineering [90]. By training specific models on extensive high-throughput DFT datasets, ML frameworks can rapidly predict WF values across vast chemical spaces, identify hidden structure–property correlations, and guide the discovery of unconventional LWF materials that may be overlooked by classical intuition. Beyond accelerating high-throughput calculations, recent ML-driven screening studies have begun to identify previously unexplored candidate LWF materials and surfaces. In particular, Schindler et al. [17] combined large-scale DFT databases with supervised ML classifiers to screen thousands of surface terminations, uncovering stable material–surface combinations exhibiting predicted WF values below 1.5–2.0 eV that had not been previously highlighted in the literature. Importantly, this approach explicitly incorporated thermodynamic stability and surface realism as selection criteria, rather than focusing solely on idealized electronic structure. Similar ML-assisted workflows applied to perovskite materials [74] have revealed non-intuitive composition–termination relationships governing WF reduction, demonstrating that data-driven models can guide the discovery of viable LWF candidates beyond manual DFT exploration. While experimental validation still remains limited, these studies represent concrete examples in which ML screening has gone beyond acceleration and has actively proposed new LWF materials and surface configurations for further investigation.

6. Stability, Processability, and Scalability

- Chemical and environmental stability: Many ultra-low WF surfaces are highly reactive: they oxidize, adsorb ambient species (e.g., O2, H2O), or restructure when exposed to air or multiple thermal/field cycles. For example, nanoscale emitters of LaB6 show extremely stable emission only when their surface is covered by lanthanum oxides (LaO, La2O3-x) [78], which retain an LWF while improving chemical robustness. Another strategy is forming protective 2D overlayers (e.g., h-BN) on LWF cores, which preserve the LWF values while shielding surfaces from contamination or oxidation. However, long-term ambient tests (months to years, under cycling) remain relatively rare in the literature.

- Processability and compatibility with device fabrication: For deployment in devices (i.e., large-area cathodes, printable electronics, and flexible substrates), LWF materials must be compatible with cost-effective deposition techniques (like solution process, thermal evaporation, sputtering, and roll-to-roll), patterning, and integration with other layers. Some polymer-based LWF electrodes (solution-processed) demonstrate ambient stability and ease of fabrication, but they often do not reach WF values as low as the best inorganic systems, and they can be used in high-temperature applications. The trade-off between performance (WF reduction) and manufacturability must be navigated.

- Scalability and uniformity: Scaling from small-area laboratory samples to device-scale (cm2 or more) introduces new challenges, such as uniformity of surface composition, maintenance of LWF over a large area, defects’ control, reproducibility, and system cost. Many screening studies identify candidate materials with excellent LWF in ideal conditions, but few address film growth, deposition yield, process tolerances, or long-term device-integration stability. For instance, while perovskite oxides with promising LWF are intellectually exciting, their thin-film growth, surface termination control, and large-area reproducibility remain open issues.

7. Emerging Applications

7.1. Vacuum and Field Emission Devices

7.2. Photocathodes and Photoemission

7.3. Optoelectronic and Energy Devices

7.4. Thermionic and Energy Conversion Devices

7.5. Quantum, Sensor, and Emerging Frontiers

8. Open Challenges and Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kahn, A. Fermi level, work function and vacuum level. Mater. Horiz. 2016, 3, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.L. Electron Emission Physics. In Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 149, pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mortreuil, F.; Villeneuve-Faure, C.; Boudou, L.; Makasheva, K.; Teyssedre, G. Charge injection phenomena at the metal/dielectric interface investigated by Kelvin probe force microscopy. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 175302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Greiner, M.T.; Lu, Z.-H. Thin-film metal oxides in organic semiconductor devices: Their electronic structures, work functions and interfaces. NPG Asia Mater. 2013, 5, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Shin, C. Impact of Equivalent Oxide Thickness on Threshold Voltage Variation Induced by Work-Function Variation in Multigate Devices. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2017, 64, 2452–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-W.; Oh, J.S.; Meyyappan, M. Cofabrication of Vacuum Field Emission Transistor (VFET) and MOSFET. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2014, 13, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Vilayurganapathy, S.; Joly, A.G.; Droubay, T.C.; Chambers, S.A.; Maldonado, J.R.; Hess, W.P. Comparison of CsBr and KBr covered Cu photocathodes: Effects of laser irradiation and work function changes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 071604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayenas, C.G.; Bebelis, S.; Ladas, S. Dependence of catalytic rates on catalyst work function. Nature 1990, 343, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Noh, M.F.; Teh, C.H.; Daik, R.; Lim, E.L.; Yap, C.C.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Ahmad Ludin, N.; Mohd Yusoff, A.R.b.; Jang, J.; Mat Teridi, M.A. The architecture of the electron transport layer for a perovskite solar cell. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 682–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, A.; Girolami, M.; Mastellone, M.; Orlando, S.; Polini, R.; Santagata, A.; Serpente, V.; Valentini, V.; Trucchi, D.M. Novel concepts and nanostructured materials for thermionic-based solar and thermal energy converters. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.F.; Celenza, T.J.; Schmitt, F.; Schwede, J.W.; Bargatin, I. Progress Toward High Power Output in Thermionic Energy Converters. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2003812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, D.H.; Schmerge, J.F. Quantum efficiency and thermal emittance of metal photocathodes. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top.-Accel. Beams 2009, 12, 074201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomenko, V.S. Handbook of Thermionic Properties; Samsonov, G.V., Ed.; Plenum Press Data Division: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Roquais, J.-M.; Vancil, B.; Green, M. Review on Impregnated and Reservoir Ba Dispenser Cathodes. In Modern Developments in Vacuum Electron Sources; Gaertner, G., Knapp, W., Forbes, R.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 33–82. [Google Scholar]

- Futamoto, M.; Nakazawa, M.; Usami, K.; Hosoki, S.; Kawabe, U. Thermionic emission properties of a single-crystal LaB6 cathode. J. Appl. Phys. 1980, 51, 3869–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, H.; Takagi, K.; Yuito, I.; Kawabe, U. Work function of LaB6. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1976, 29, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, P.; Antoniuk, E.R.; Cheon, G.; Zhu, Y.; Reed, E.J. Discovery of Stable Surfaces with Extreme Work Functions by High-Throughput Density Functional Theory and Machine Learning. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2401764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.; Booske, J.; Morgan, D. Understanding and Controlling the Work Function of Perovskite Oxides Using Density Functional Theory. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 5471–5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Hansmann, P. Tuning the work function in transition metal oxides and their heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 235116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minohara, M.; Yasuhara, R.; Kumigashira, H.; Oshima, M. Termination layer dependence of Schottky barrier height for La0.6Sr0.4MnO3/Nb: SrTiO3 heterojunctions. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 235322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.-Y.; Iitaka, T.; Yang, X.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.-J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.-X. Enhanced thermionic emission performance of LaB6 by Ce doping. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 760, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tang, J.; Yuan, J.; Ma, J.; Shinya, N.; Nakajima, K.; Murakami, H.; Ohkubo, T.; Qin, L.C. Nanostructured LaB6 field emitter with lowest apical work function. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 3539–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, K.; Aizawa, T.; Ohmi, S.-I. Fabrication of monolayer h-BN/LaB6 heterostructure thin film with low work function and high chemical stability. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 669, 160478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpente, V.; Bellucci, A.; Girolami, M.; Mastellone, M.; Mezzi, A.; Kaciulis, S.; Carducci, R.; Polini, R.; Valentini, V.; Trucchi, D.M. Ultra-thin films of barium fluoride with low work function for thermionic-thermophotovoltaic applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 249, 122989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossenberger, F.; Roman, T.; Forster-Tonigold, K.; Groß, A. Change of the work function of platinum electrodes induced by halide adsorption. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2014, 5, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Körber, C.; Wachau, A.; Säuberlich, F.; Gassenbauer, Y.; Harvey, S.P.; Proffit, D.E.; Mason, T.O. Transparent Conducting Oxides for Photovoltaics: Manipulation of Fermi Level, Work Function and Energy Band Alignment. Materials 2010, 3, 4892–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, G.I.; Sokolovsky, E.A. Dependence of effective work function for LaB6 on surface conditions. Phys. Scr. 1997, 1997, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, D.Y. On the correlation between surface roughness and work function in copper. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 064708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Peng, S.; Wang, F.; Ou, J.; Li, C.; Li, W. Linear relation between surface roughness and work function of light alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 692, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turetta, N.; Sedona, F.; Liscio, A.; Sambi, M.; Samorì, P. Au(111) Surface Contamination in Ambient Conditions: Unravelling the Dynamics of the Work Function in Air. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8, 2100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Kant, R. Theory of Work Function and Potential of Zero Charge for Metal Nanostructured and Rough Electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 13059–13069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Guha, P.; Thapa, R.; Selvaraj, S.; Kumar, M.; Rakshit, B.; Dash, T.; Bar, R.; Ray, S.K.; Satyam, P.V. Tuning the work function of randomly oriented ZnO nanostructures by capping with faceted Au nanostructure and oxygen defects: Enhanced field emission experiments and DFT studies. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 125701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, M.Y.; Lee, S.; Jhi, S.H. Super low work function of alkali-metal-adsorbed transition metal dichalcogenides. J. Phys. Condens. Matter Inst. Phys. J. 2017, 29, 315702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavkhelidze, A. Geometry-induced electron doping in periodic semiconductor nanostructures. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostructures 2014, 60, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavkhelidze, A.; Bibilashvili, A.; Jangidze, L.; Gorji, N.E. Fermi-Level Tuning of G-Doped Layers. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimov, N.; Staykov, A.; Kusdhany, M.I.M.; Lyth, S.M. Tailoring the work function of graphene via defects, nitrogen-doping and hydrogenation: A first principles study. Nanotechnology 2023, 34, 415001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Jacobs, R.; Ma, T.; Chen, D.; Booske, J.; Morgan, D. Work Function: Fundamentals, Measurement, Calculation, Engineering, and Applications. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2023, 19, 037001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Ma, X.; Chen, J.; Wan, X.; Chen, Y.; Feng, Y. Molecularly Tailored Self-Assembled Monolayers as Hole Transfer Materials Enabling High-Performance Organic Photovoltaics. ACS Energy Lett. 2025, 10, 5567–5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomyakov, P.A.; Giovannetti, G.; Rusu, P.C.; Brocks, G.; van den Brink, J.; Kelly, P.J. First-principles study of the interaction and charge transfer between graphene and metals. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 195425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokdam, M.; Brocks, G.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Kelly, P.J. Schottky barriers at hexagonal boron nitride/metal interfaces: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 085415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Chang, S.; Bargatin, I.; Wang, N.C.; Riley, D.C.; Wang, H.; Schwede, J.W.; Provine, J.; Pop, E.; Shen, Z.X.; et al. Engineering Ultra-Low Work Function of Graphene. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 6475–6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, M.T.; Chai, L.; Helander, M.G.; Tang, W.-M.; Lu, Z.-H. Transition Metal Oxide Work Functions: The Influence of Cation Oxidation State and Oxygen Vacancies. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 4557–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Park, J.; Xu, B.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Qi, Y.; Luo, J. Unusual aliovalent doping effects on oxygen non-stoichiometry in medium-entropy compositionally complex perovskite oxides. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucchi, D.M.; Bellucci, A.; Girolami, M.; Calvani, P.; Cappelli, E.; Orlando, S.; Polini, R.; Silvestroni, L.; Sciti, D.; Kribus, A. Solar Thermionic-Thermoelectric Generator (ST2G): Concept, Materials Engineering, and Prototype Demonstration. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1802310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavkhelidze, A.; Bibilashvili, A.; Jangidze, L.; Shimkunas, A.; Mauger, P.; Rempfer, G.F.; Almaraz, L.; Dixon, T.; Kordesch, M.E.; Katan, N.; et al. Observation of quantum interference effect in solids. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 2006, 24, 1413–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sun, W.; Xu, H.; Qiu, H.; Xiao, G. Theoretical study on the Cs/Cs-O adsorbed graphene/semiconductor heterojunction anode for thermionic converters. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2024, 6, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.J.; Blott, B.H.; Hopkins, B.J. Work Functions of Cesium on (100) and (110) Oriented Faces of Tungsten Single Crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1967, 11, 361–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hanrahan, C.P.; Arias, J.; Martin, R.M.; Metiu, H. Local modifications of the surface work function by potassium adsorption. Surf. Sci. 1985, 161, L543–L548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkhestov, R.K.; Alchagirov, B.B.; Kegadueva, Z.A. Electron work function of Potassium-Cesium-Rubidium melts. In Proceedings of the 2014 Tenth International Vacuum Electron Sources Conference (IVESC), Saint Petersburg, Russia, 30 June–4 July 2014; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bellucci, A.; Mastellone, M.; Girolami, M.; Serpente, V.; Generosi, A.; Paci, B.; Mezzi, A.; Kaciulis, S.; Carducci, R.; Polini, R.; et al. Nanocrystalline lanthanum boride thin films by femtosecond pulsed laser deposition as efficient emitters in hybrid thermionic-photovoltaic energy converters. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 513, 145829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, A.; Mastellone, M.; Orlando, S.; Girolami, M.; Generosi, A.; Paci, B.; Soltani, P.; Mezzi, A.; Kaciulis, S.; Polini, R.; et al. Lanthanum (oxy)boride thin films for thermionic emission applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 479, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Jacobs, R.; Booske, J.; Morgan, D. Work Function Trends and New Low-Work-Function Boride and Nitride Materials for Electron Emission Applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 17400–17410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzi, A.; Soltani, P.; Kaciulis, S.; Bellucci, A.; Girolami, M.; Mastellone, M.; Trucchi, D.M. Investigation of work function and chemical composition of thin films of borides and nitrides. Surf. Interface Anal. 2018, 50, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Q.; Weidenthaler, C.; Wu, A.; Gao, W.; Pei, Q.; Yan, H.; Cui, J.; Wu, H.; et al. Barium chromium nitride-hydride for ammonia synthesis. Chem Catal. 2021, 1, 1042–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.; Morgan, D.; Booske, J. Work function and surface stability of tungsten-based thermionic electron emission cathodes. APL Mater. 2017, 5, 116105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Qie, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, C.; Yang, S.; Li, Q.; Sun, Q. Enhancing Electron Emission of Hf with an Ultralow Work Function by Barium–Oxygen Coatings. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 2806–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzi, A.; Bolli, E.; Kaciulis, S.; Bellucci, A.; Paci, B.; Generosi, A.; Mastellone, M.; Serpente, V.; Trucchi, D.M. Multi-Technique Approach for Work Function Exploration of Sc2O3 Thin Films. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, D.M.; Gross, S.J.; Balk, T.J.; Beck, M.J.; Booske, J.; Busbaher, D.; Jacobs, R.; Kordesch, M.E.; Mitsdarffer, B.; Morgan, D.; et al. Frontiers in Thermionic Cathode Research. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2018, 65, 2061–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagwijn, P.M.; Frenken, J.W.M.; van Slooten, U.; Duine, P.A. A model system for scandate cathodes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1997, 111, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seif, M.N.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, X.; Balk, T.J.; Beck, M.J. Sc-Containing (Scandate) Thermionic Cathodes: Mechanisms for Sc Enhancement of Emission. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 3523–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seif, M.N.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, X.; Balk, T.J.; Beck, M.J. Sc-Containing (Scandate) Thermionic Cathodes: Fabrication, Microstructure, and Emission Performance. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 3513–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordesch, M.E.; Vaughn, J.M.; Wan, C.; Jamison, K.D. Model scandate cathodes investigated by thermionic-emission microscopy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2011, 29, 04E102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.S.; Jacobs, R.; Morgan, D.; Booske, J. Time dependence of SrVO3 thermionic electron emission properties. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 135, 055104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tountas, M.; Topal, Y.; Polydorou, E.; Soultati, A.; Verykios, A.; Kaltzoglou, A.; Papadopoulos, T.A.; Auras, F.; Seintis, K.; Fakis, M.; et al. Low Work Function Lacunary Polyoxometalates as Electron Transport Interlayers for Inverted Polymer Solar Cells of Improved Efficiency and Stability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 22773–22787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, M.; Zhu, C.; Koeck, F.A.M.; Nemanich, R.J. Thermionic electron emission from nitrogen-doped homoepitaxial diamond. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2010, 19, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeck, F.A.M.; Nemanich, R.J.; Lazea, A.; Haenen, K. Thermionic electron emission from low work-function phosphorus doped diamond films. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2009, 18, 789–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpente, V.; Bellucci, A.; Girolami, M.; Mastellone, M.; Iacobucci, S.; Ruocco, A.; Trucchi, D.M. Combined electrical resistivity-electron reflectivity measurements for evaluating the homogeneity of hydrogen-terminated diamond surfaces. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2021, 114, 108290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, A.; Pede, B.; Mastellone, M.; Valentini, V.; Polini, R.; Trucchi, D.M. Thermionic performance of nanocrystalline diamond/silicon structures under concentrated solar radiation. Ceram. Int. 2022, 49, 24351–24355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Liu, Y.; Day, C.M.; Little, S.A. Enhanced electron emission from functionalized carbon nanotubes with a barium strontium oxide coating produced by magnetron sputtering. Carbon 2007, 45, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Günther, S.; Wintterlin, J.; Bocquet, M.L. Periodicity, work function and reactivity of graphene on Ru(0001) from first principles. New J. Phys. 2010, 12, 043041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Yang, D.; Chen, L.; Liu, D.; Cai, M.; Fan, X. Design and adjustment of the graphene work function via size, modification, defects, and doping: A first-principle theory study. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusupov, K.; Björk, J.; Rosen, J. A systematic study of work function and electronic properties of MXenes from first principles. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 3976–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, P.; Riley, D.C.; Bargatin, I.; Sahasrabuddhe, K.; Schwede, J.W.; Sun, S.; Pianetta, P.; Shen, Z.X.; Howe, R.T.; Melosh, N.A. Surface Photovoltage-Induced Ultralow Work Function Material for Thermionic Energy Converters. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 2436–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Jacobs, R.; Booske, J.; Morgan, D. Discovery and engineering of low work function perovskite materials. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 12778–12790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahos, V.; Booske, J.H.; Morgan, D. Ab initio investigation of barium-scandium-oxygen coatings on tungsten for electron emitting cathodes. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 054207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeck, F.A.M.; Nemanich, R.J. Substrate-diamond interface considerations for enhanced thermionic electron emission from nitrogen doped diamond films. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 113707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Sami, S.N.; Diaz, L.; Sanati, M.; Joshi, R.P. Evaluation of electron currents from cesium-coated tungsten emitter arrays with inclusion of space charge effects, workfunction changes, and screening. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Nanotechnol. Microelectron. Mater. Process. Meas. Phenom. 2021, 39, 054201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, W.; Tang, S.; Tang, J.; Qin, L.C. Effects of low work-function lanthanum oxides on stable electron field emissions from nanoscale emitters. Nanoscale Adv. 2022, 4, 4669–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzi, A.; Bolli, E.; Kaciulis, S.; Mastellone, M.; Girolami, M.; Serpente, V.; Bellucci, A.; Carducci, R.; Polini, R.; Trucchi, D.M. Work function and negative electron affinity of ultrathin barium fluoride films. Surf. Interface Anal. 2020, 52, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, T.; Chen, X.; Bai, F.; Genco, A.; Wang, H.; Chen, C.; Chen, P.; Mazzeo, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Highly Conductive Alkaline-Earth Metal Electrodes: The Possibility of Maintaining Both Low Work Function and Surface Stability for Organic Electronics. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 2000206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.S.; Lin, L.; Jacobs, R.; Morgan, D.; Booske, J. SrVO3 electron emission cathodes with stable, >250 mA/cm2 current density. In Proceedings of the 2023 24th International Vacuum Electronics Conference (IVEC), Chengdu, China, 25–28 April 2023; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Fukagawa, H.; Suzuki, K.; Ito, H.; Inagaki, K.; Sasaki, T.; Oono, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Morii, K.; Shimizu, T. Understanding coordination reaction for producing stable electrode with various low work functions. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Kim, A. Absolute work function measurement by using photoelectron spectroscopy. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2021, 31, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helander, M.G.; Greiner, M.T.; Wang, Z.B.; Lu, Z.H. Pitfalls in measuring work function using photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 2602–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melitz, W.; Shen, J.; Kummel, A.C.; Lee, S. Kelvin probe force microscopy and its application. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2011, 66, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, A.; Mastellone, M.; Girolami, M.; Serpente, V.; Sani, E.; Sciti, D.; Trucchi, D.M. Thermionic emission measurement of sintered lanthanum hexaboride discs and modelling of their solar energy conversion performance. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 20736–20739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, E.; Guedj, C.; Mariolle, D.; Licitra, C.; Renault, O.; Bertin, F.; Chabli, A.; Imbert, G.; Delsol, R. Electronic and chemical properties of the TaN/a-SiOC:H stack studied by photoelectron spectroscopy for advanced interconnects. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 073708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, C.J.; Binggeli, N.; Baldereschi, A. Deriving accurate work functions from thin-slab calculations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1999, 11, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawole, O.C.; De, D.K.; Olawole, O.F.; Lamba, R.; Joel, E.S.; Oyedepo, S.O.; Ajayi, A.A.; Adegbite, O.A.; Ezema, F.I.; Naghdi, S.; et al. Progress in the experimental and computational methods of work function evaluation of materials: A review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramprasad, R.; Batra, R.; Pilania, G.; Mannodi-Kanakkithodi, A.; Kim, C. Machine learning in materials informatics: Recent applications and prospects. npj Comput. Mater. 2017, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Jacobs, R.; Booske, J.; Morgan, D. Understanding the interplay of surface structure and work function in oxides: A case study on SrTiO3. APL Mater. 2020, 8, 071110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, S.A.; Sushko, P.V. Influence of crystalline order and defects on the absolute work functions and electron affinities of TiO2- and SrO-terminated n−SrTiO3 (001). Phys. Rev. Mater. 2019, 3, 125803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Tang, J.; Uzuhashi, J.; Ohkubo, T.; Hayami, W.; Yuan, J.; Takeguchi, M.; Mitome, M.; Qin, L.C. A stable LaB6 nanoneedle field-emission point electron source. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 2787–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baryshev, S.V.; Wang, E.; Jing, C.; Jabotinski, V.; Antipov, S.; Kanareykin, A.D.; Belomestnykh, S.; Ben-Zvi, I.; Chen, L.; Wu, Q.; et al. Cryogenic operation of planar ultrananocrystalline diamond field emission source in SRF injector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 053505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, M.; Tang, S.; Huang, K.; Guan, H.; Zhan, R.; Liang, C.; Chen, C.; Shen, Y.; Deng, S. Ultrabright LaB6 nanoneedle field emission electron source with low vacuum compatibility. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, B.; Wu, A.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Li, Y. MXene-tailored CNT cold cathodes and self-powered electron emitters toward plasma generation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 127, 101605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Shi, F.; Zhang, R.; Gan, L.; Jia, T.; Du, J.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, Y. Cs/O co-adsorption on C-doped GaAs surface: From first-principles simulation to experiment. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 075017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, S. CsF, Cs as a low work function layer on the GaAs photocathode. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 1970, 2, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, J.; Gaowei, M.; Mondal, K.P.; Wang, E.; Sadowski, J.T.; Al-Mahboob, A.; Tong, X. Single layer graphene protective layer on GaAs photocathodes for spin-polarized electron source. APL Mater. 2025, 13, 061101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Rahman, O.; Biswas, J.; Skaritka, J.; Inacker, P.; Liu, W.; Napoli, R.; Paniccia, M. High-intensity polarized electron gun featuring distributed Bragg reflector GaAs photocathode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 124, 254101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Li, B.; Xu, B.; Wang, Z. Hybrid Perovskites and 2D Materials in Optoelectronic and Photocatalytic Applications. Crystals 2023, 13, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vito, A.; Pecchia, A.; Auf der Maur, M.; Di Carlo, A. Nonlinear Work Function Tuning of Lead-Halide Perovskites by MXenes with Mixed Terminations. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1909028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, R.; Valentini, V.; Bolli, E.; Mastellone, M.; Serpente, V.; Mezzi, A.; Tortora, L.; Colantoni, E.; Bellucci, A.; Polini, R.; et al. Low Electron Affinity Silicon/Nanocrystalline Diamond Heterostructures for Photon-Enhanced Thermionic Emission. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, A.; Raoui, Y.; Bolli, E.; Mastellone, M.; Salerno, R.; Valentini, V.; Polini, R.; Mezzi, A.; Di Carlo, A.; Vesce, L.; et al. Photon-enhanced thermionic emission devices with perovskite photovoltaic anodes for conversion of concentrated sunlight. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 286, 113588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, A.; Girolami, M.; Mastellone, M.; Mezzi, A.; Serpente, V.; Orlando, S.; Santagata, A.; Polini, R.; Kribus, A.; Trucchi, D.M. Demonstrating black-diamond-based high-temperature solar cells. Joule 2026, 10, 102223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, A.; García-Linares, P.; Martí, A.; Trucchi, D.M.; Datas, A. A Three-Terminal Hybrid Thermionic-Photovoltaic Energy Converter. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, A.; Mastellone, M.; Serpente, V.; Girolami, M.; Kaciulis, S.; Mezzi, A.; Trucchi, D.M.; Antolín, E.; Villa, J.; Linares, P.G.; et al. Photovoltaic Anodes for Enhanced Thermionic Energy Conversion. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 1364–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, A.; Caposciutti, G.; Antonelli, M.; Trucchi, D.M. Techno-Economic Evaluation of Future Thermionic Generators for Small-Scale Concentrated Solar Power Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwede, J.W.; Bargatin, I.; Riley, D.C.; Hardin, B.E.; Rosenthal, S.J.; Sun, Y.; Schmitt, F.; Pianetta, P.; Howe, R.T.; Shen, Z.; et al. Photon-enhanced thermionic emission for solar concentrator systems. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varpula, A.; Tappura, K.; Prunnila, M. Si, GaAs, and InP as cathode materials for photon-enhanced thermionic emission solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2015, 134, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.-S.; Kopas, C.J.; Cansizoglu, H.; Mutus, J.Y.; Yadavalli, K.; Kim, T.-H.; Kramer, M.; King, A.H.; Zhou, L. Correlating aluminum layer deposition rates, Josephson junction microstructure, and superconducting qubits’ performance. Acta Mater. 2025, 284, 120631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, A.; McCloskey, D.J.; Dontschuk, N.; Al Hashem, H.N.; Murdoch, B.J.; Stacey, A.; Prawer, S.; Ahnood, A. Impact of surface treatments on the electron affinity of nitrogen-doped ultrananocrystalline diamond. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 656, 159710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Su, Y.; Ennaji, I.; Khojastehnezhad, A.; Siaj, M. Encapsulation of few-layered MoS2 on electrochemical-treated BiVO4 nanoarray photoanode: Simultaneously improved charge separation and hole extraction towards efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Kim, H. Recent advances in MXene gas sensors: Synthesis, composites, and mechanisms. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2025, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material Class | Representative Examples | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Alkali compounds | Cs, CsO2, K-Cs | Thermionic cathodes, photocathodes |

| Rare-earth borides | LaB6 | High-temperature emission devices |

| Ba-based systems | BaO, Ba-Sc-O | Thermionic cathode, photocathodes |

| Perovskites | SrVO3, SrTiO3 | Robust emitters and electronics |

| Carbon-based materials | Diamond, CNT | Vacuum electronics, energy conversion devices |

| 2D heterostructures | Graphene, h-BN | Interface engineering, protective layers, and WF tuning |

| Hybrid/organic layers | Polymer interlayers | Charge injection, flexible electronics |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bellucci, A. The Quest for Low Work Function Materials: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities. Crystals 2026, 16, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010047

Bellucci A. The Quest for Low Work Function Materials: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleBellucci, Alessandro. 2026. "The Quest for Low Work Function Materials: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities" Crystals 16, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010047

APA StyleBellucci, A. (2026). The Quest for Low Work Function Materials: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities. Crystals, 16(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010047