Effects of 147 MeV Kr Ions on the Structural, Optical and Luminescent Properties of Gd3Ga5O12

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

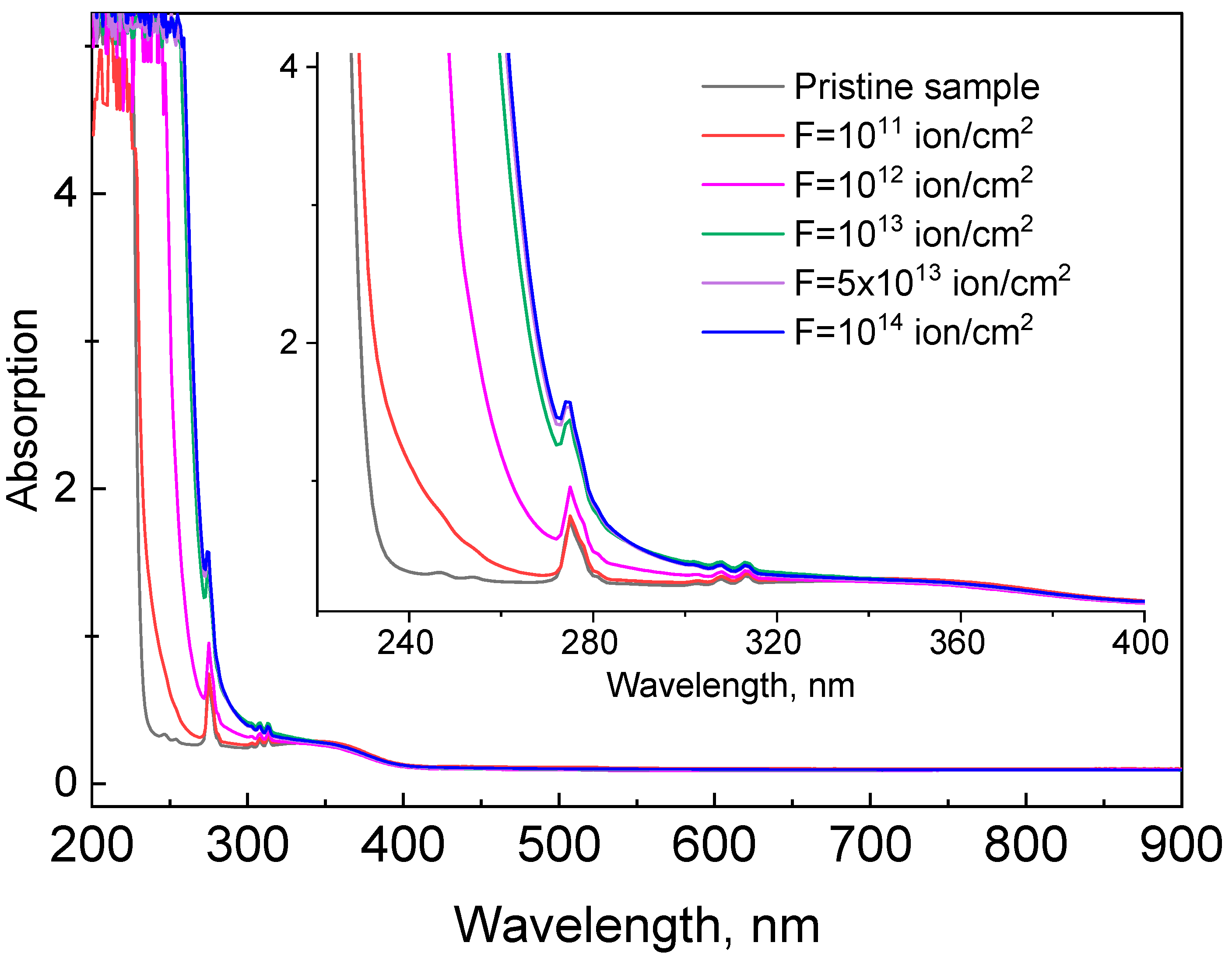

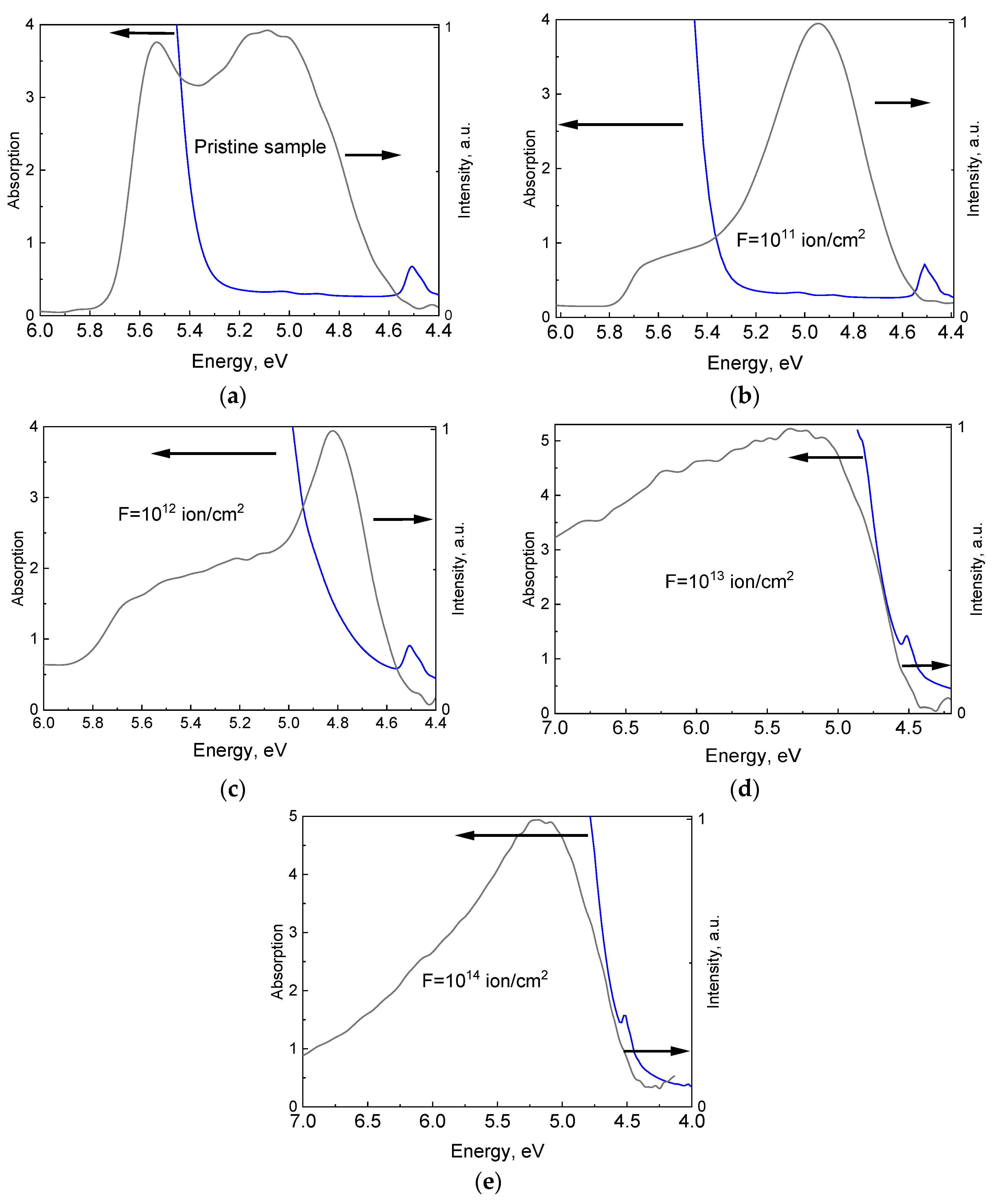

3.1. Absorption Spectra Analysis

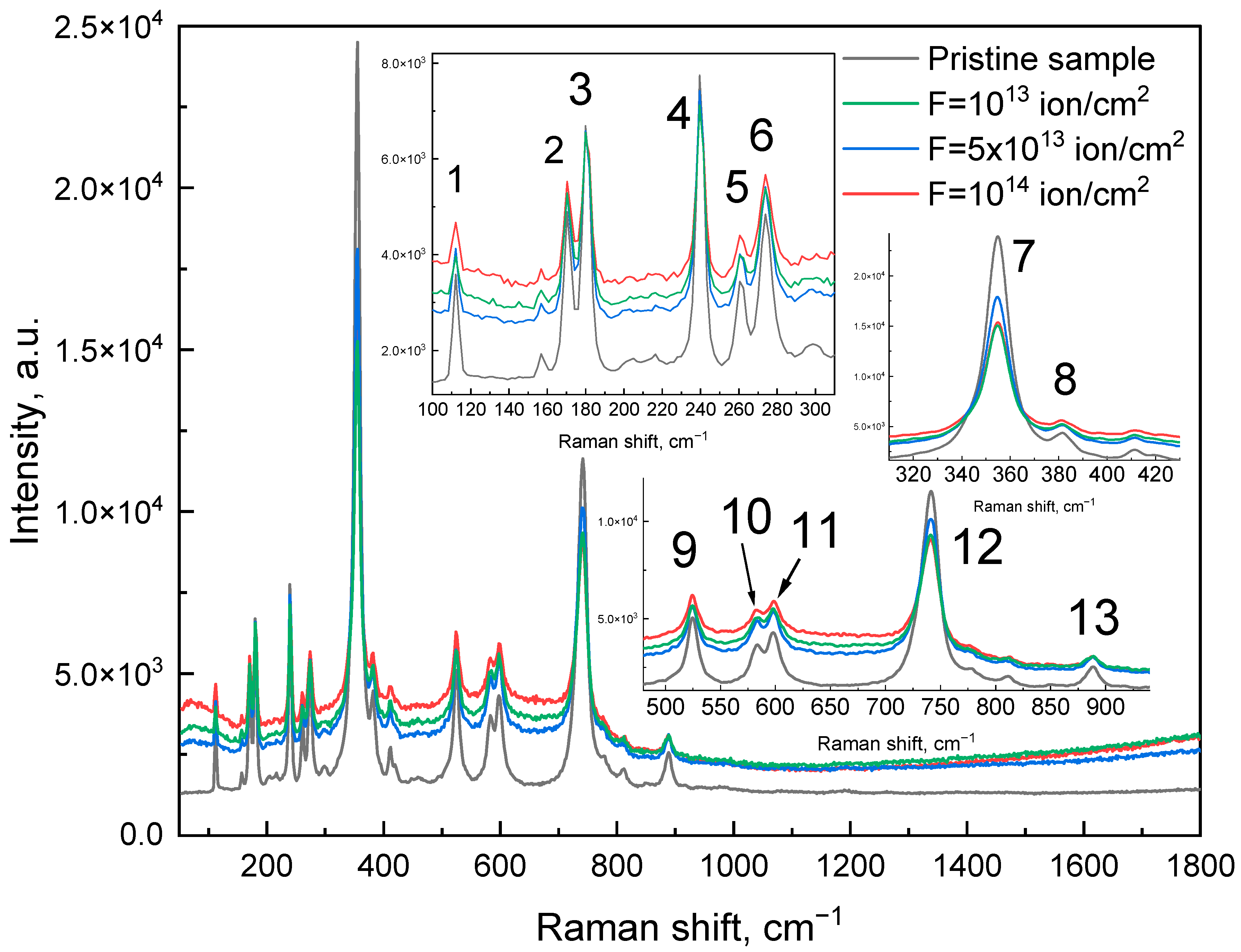

3.2. Raman Spectra Analysis

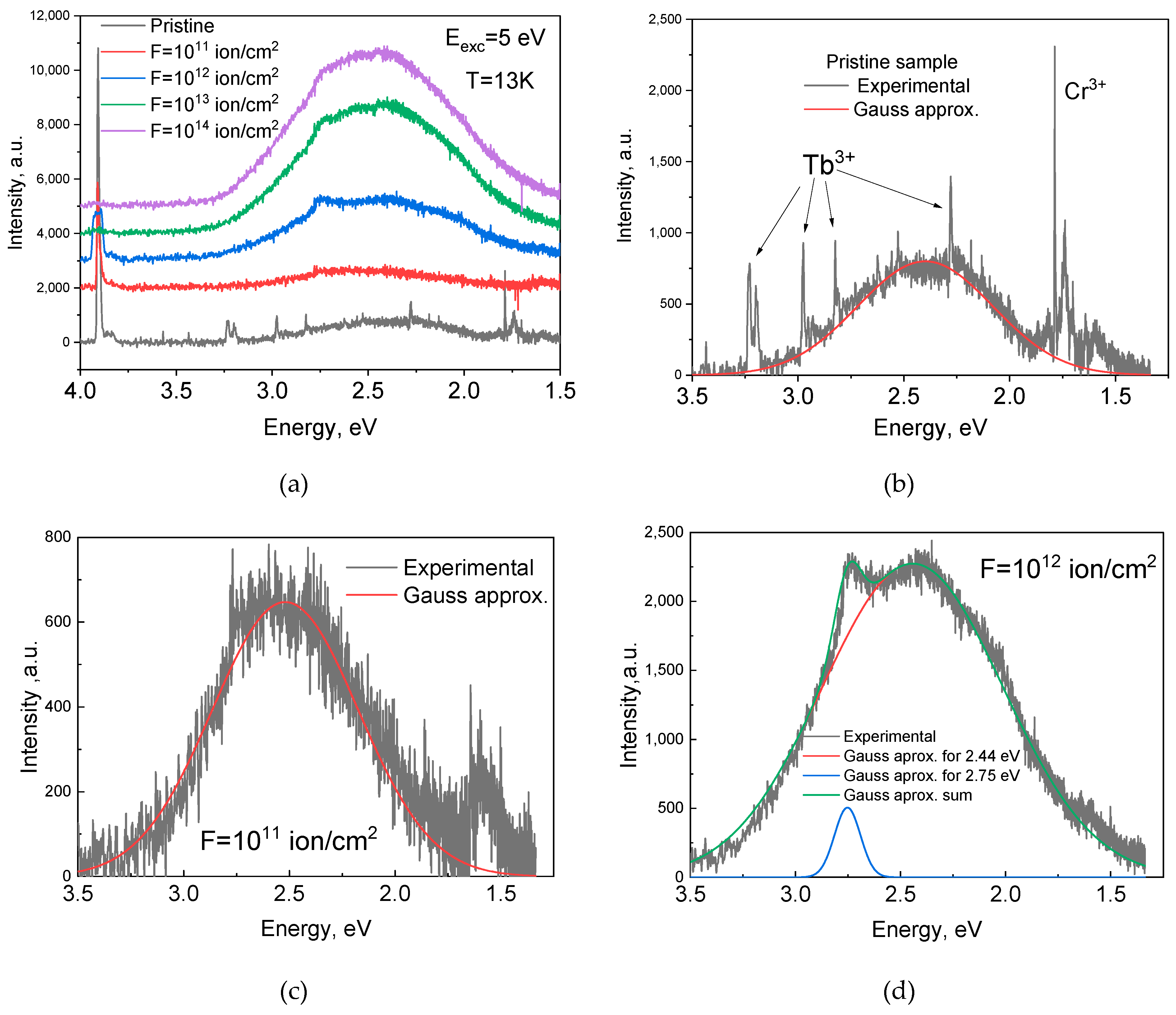

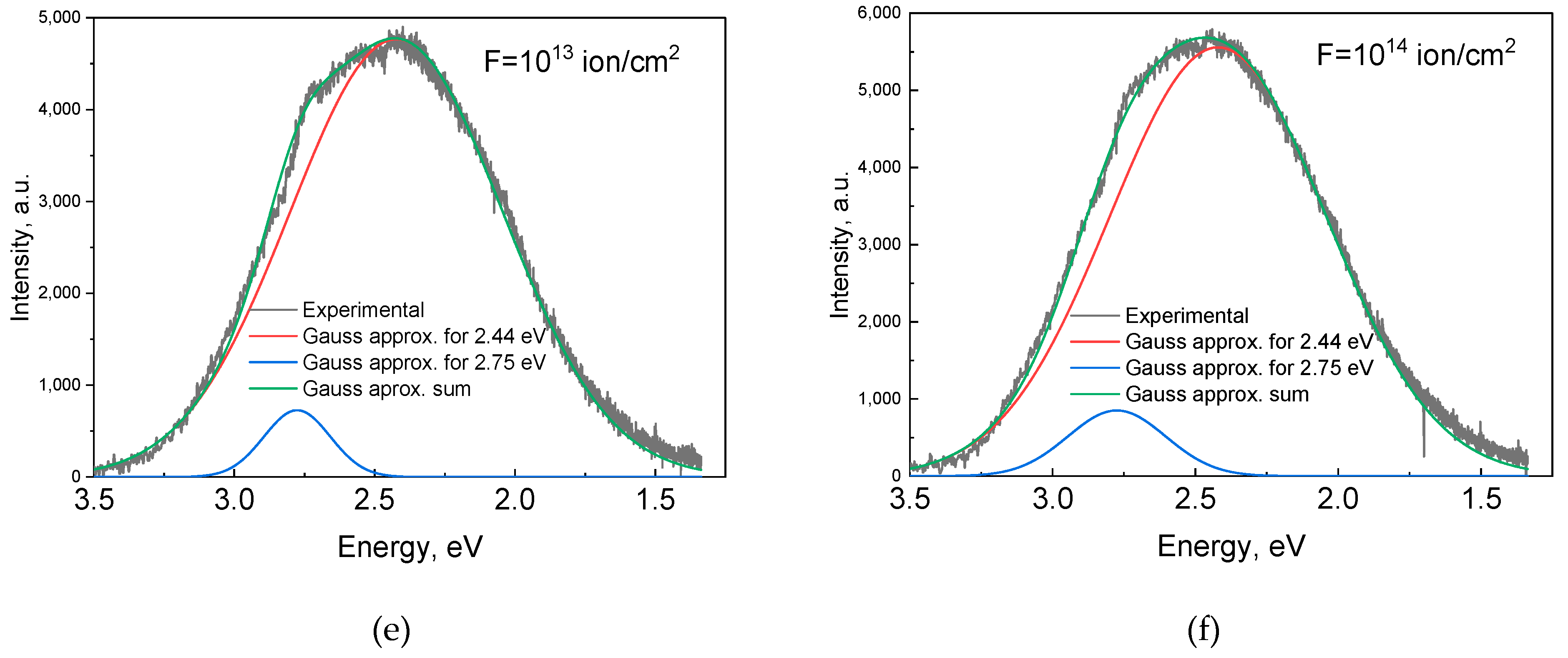

3.3. Luminescence Spectra

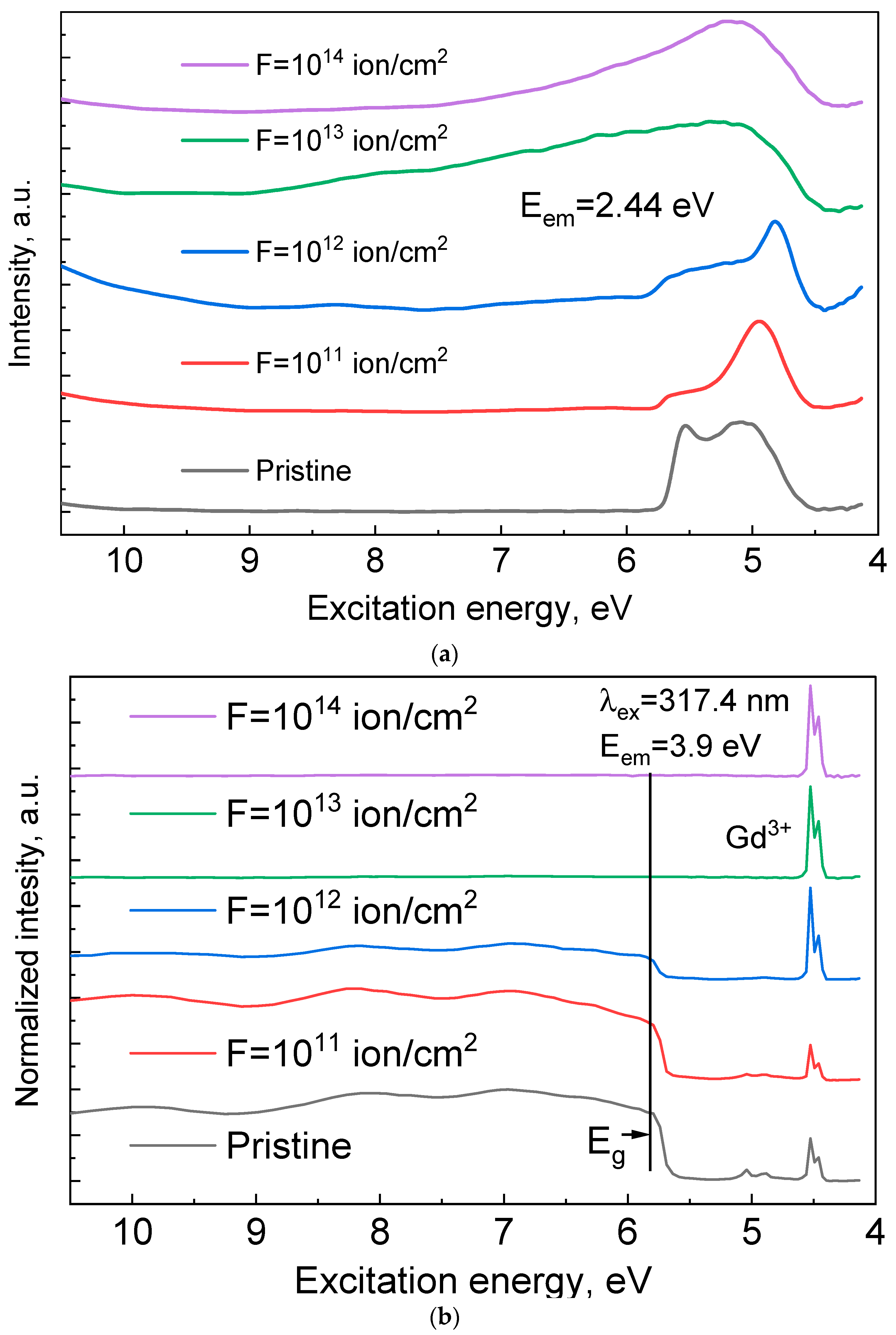

3.4. Luminescence Excitation Spectra

3.5. Correlation Between Absorption (300 K) and Excitation Spectra (13 K)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Kane, D.F.; Sadagopan, V.; Geiss, E.A.; Mandel, E. Crystal Growth and Characterization of Gadolinium Gallium Garnet. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1973, 120, 1272–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-N.; Ching, W.Y.; Brickeen, B.K. Electronic structure and bonding in garnet crystals Electronic structure and bonding in garnet crystals Gd3Sc2Ga3O12, Gd3Sc2Al3O12, and Gd3Ga3O12 compared to Y3Al3O12. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, K.; Haneef, H.F.; Collins, R.W.; Podraza, N.J. Optical Properties of Single-Crystal Gd3Ga5O12 from the Infrared to the Ultraviolet. Phys. Status Solidi B 2015, 252, 2191–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Li, T.; Xu, J. Growth of epitaxial substrate Gd3Ga3O12 (GGG) single crystal through pure GGG phase polycrystalline material. J. Cryst. Growth 2002, 237–239, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvorotka, I.I.; Sugak, D.Y.; Wierzbicka, A.; Wittlin, A.; Przybylińska, H.; Barzowska, J.; Barcz, A.J.; Berkowski, M.; Domagała, J.Z.; Mahlik, S.; et al. Optical Properties of Pure and Ce3+-Doped Gadolinium Gallium Garnet Crystals and Epitaxial Layers. J. Lumin. 2015, 164, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, M.M.; Neshchimenko, V.V.; Shavlyuk, V.V. The effects of binding type on luminescence LED phosphor based on GGG/Ce3+. Opt. Mater. 2014, 38, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalaisamy, T.K.; Saravanakumar, S.; Butkute, S.; Kareiva, A.; Saravanan, R. Structure and Charge Density of Ce-Doped GGG. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 1920–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; You, Z.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Ma, E.; Tu, C. Spectroscopy of Highly Doped Er3+:GGG and Er3+/Pr3+:GGG. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 215406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; You, Z.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Tu, C. Optical Properties of Dy3+ in GGG. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2010, 43, 075402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkute, S.; Zabiliute, A.; Skaudzius, R.; Zukauskas, A.; Kareiva, A. Sol-Gel Synthesis and Substitution in Ga-Garnets. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2015, 76, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Meng, B.; Rao, X.; Zhou, Y. Research of material removal and deformation mechanism for single crystal GGG (Gd3Ga5O12) based on varied-depth nanoscratch testing. Mater. Des. 2017, 125, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Rao, X. Investigation on surface/subsurface deformation mechanism and mechanical properties of GGG single crystal induced by nanoindentation. Appl. Opt. 2018, 57, 3661–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, F.; Huang, H. Deformation characteristics and surface generation modelling of crack-free grinding of GGG single crystals. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 279, 116577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugak, D.; Syvorotka, I.I.; Yakhnevych, U.; Buryy, O.; Vakiv, M.; Ubizskii, S.; Włodarczyk, D.; Zhydachevskyy, Y.; Pieniążek, A.; Jakiela, R.; et al. Investigation of Co Ions Diffusion in Gd3Ga5O12 Single Crystals. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2018, 133, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshmi, C.P.; Ramesh, A.R.; Suresh, A.; Jaiswal-Nagar, D. Magnetic, magnetocaloric and optical properties of nano Gd3Ga5O12garnet synthesized by citrate sol-gel method. Int. J. Nano Dimens. 2025, 16, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchechko, A.; Kostyk, L.; Varvarenko, S.; Tsvetkova, O.; Kravets, O. Green-Emitting Gd3Ga5O12:Tb3+ Nanoparticles Phosphor: Synthesis, Structure, and Luminescence. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanić, B.; Bettinelli, M.; Radenković, B.; Despotović-Zrakić, M.; Bogdanović, Z. Optical spectroscopy of nanocrystalline Gd3Ga5O12 doped with Eu3+ and high pressures. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 132, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillard, A.; Douissard, P.-A.; Loiko, P.; Martin, T.; Mathieu, E.; Camy, P. Terbium-doped gadolinium garnet thin films grown by liquid phase epitaxy for scintillation detectors. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 20560–20568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollesen, L.; Douissard, P.-A.; Pauwels, K.; Baillard, A.; Loiko, P.; Brasse, G.; Mathieu, J.; Simeth, S.J.; Kratz, M.; Dujardin, C.; et al. Microstructured growth by liquid phase epitaxy of scintillating Gd3Ga5O12(GGG) doped with Eu3+. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xu, J.; Murakami, H.; Yamahara, H.; Seki, M.; Tabata, H.; Tonouchi, M. Terahertz Time-Domain Spectroscopy of Substituted Gadolinium Gallium Garnet. Condens. Matter 2025, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yousaf, M.; Ahmed, J.; Bibi, B.; Noor, A.; Alhokbany, N.; Sajid, M.; Nazar, A.; Shah, M.A.K.Y.; Guo, X.; et al. Gd3Ga5O12: A wide bandgap semiconductor electrolyte for ceramic fuel cells, effective at temperatures below 500 C. J. Rare Earths 2025, 43, 2248–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzbieciak-Piecka, K.; Sójka, M.; Tian, F.; Li, J.; Zych, E.; Marciniak, L. The comparison of the thermometric performance of optical ceramics, microcrystals and nanocrystals of Cr3+-doped Gd3Ga5O12 garnets. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 963, 171284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama, N.; Kodama, S.; Bartosiewicz, K.; Fujiwara, C.; Yanase, I.; Takeda, H. Modification of Photoluminescence Wavelength and Decay Constant of Cr:Gd3Ga5O12 Substituted by Ca/Si Cation Pair. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2024, 132, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaura, M.; Zen, H.; Watanabe, S.; Masai, H.; Kamada, K.; Kim, K.J.; Ueda, J. Relationship between Ce3+ 5d1 Level, Conduction-Band Bottom, and Shallow Electron Trap Level in Gd3Ga5O12:Ce and Gd3Al1Ga4O12:Ce Crystals Studied via Pump-Probe Absorption Spectroscopy. Opt. Mater. X 2025, 25, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, O.A.; Balakrishnan, G.; Paul, D.M.; Yethiraj, M.; McIntyre, G.J.; Wills, A.S. Field Induced Magnetic Order in the Frustrated Magnet Gadolinium Gallium Garnet. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2009, 145, 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deen, P.P.; Florea, O.; Lhotel, E.; Jacobsen, H. Updating the Phase Diagram of the Archetypal Frustrated Magnet Gd3Ga5O12. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 014419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackville Hamilton, A.C.; Lampronti, G.I.; Rowley, S.E.; Dutton, S.E. Enhancement of the Magnetocaloric Effect Driven by Changes in the Crystal Structure of Al-Doped GGG, Gd3Ga5−xAlxO12 (0 ≤ x ≤ 5). J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2014, 26, 116001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhao, J.; Gao, L.; Ma, H.; Oimod, H.; Zhu, H.; Li, Q.; Su, T.; Zhu, H.; Tegus, O.; et al. Influence of High-Pressure Heat Treatment on Magnetocaloric Effects and Magnetic Phase Transition in Single Crystal Gd3Ga5O12. J. Rare Earths 2024, 42, 2112–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukalkin, Y.G.; Shtirts, V.R. Radiation Amorphization and Recovery of Crystal Structure in Gd3Ga5O12 Single Crystals. Phys. Status Solidi A 1994, 144, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironova-Ulmane, N.; Sildos, I.; Vasil’chenko, E.; Chikvaidze, G.; Skvortsova, V.; Kareiva, A.; Muñoz-Santiuste, J.E.; Pareja, R.; Elsts, E.; Popov, A.I. Optical Absorption and Raman Studies of Neutron-Irradiated Gd3Ga5O12 Single Crystals. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2018, 435, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potera, P.; Matkovskii, A.; Sugak, D.; Grigorjeva, L.; Millers, D.; Pankratov, V. Transient Color Centers in GGG Crystals. Radiat. Eff. Defects Solids 2002, 157, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potera, P.; Ubizskii, S.; Sugak, D.; Schwartz, K. Induced Absorption in Gadolinium Gallium Garnet Irradiated by High-Energy 235U Ions. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2010, 117, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karipbayev, Z.T.; Kumarbekov, K.; Manika, I.; Dauletbekova, A.; Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Sugak, D.; Ubizskii, S.B.; Akilbekov, A.; Suchikova, Y.; Popov, A.I. Optical, Structural, and Mechanical Properties of Gd3Ga5O12 Single Crystals Irradiated with 84Kr+ Ions. Phys. Status Solidi B 2022, 259, 2100415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meftah, A.; Costantini, J.M.; Khalfaoui, N.; Boudjadar, S.; Stoquert, J.P.; Studer, F.; Toulemonde, M. Experimental Determination of Track Cross-Section in Gd3Ga5O12 and Comparison to the Inelastic Thermal Spike Model Applied to Several Materials. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2005, 237, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulemonde, M.; Meftah, A.; Costantini, J.M.; Schwartz, K.; Trautmann, C. Out-of-Plane Swelling of Gadolinium Gallium Garnet Induced by Swift Heavy Ions. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 1998, 146, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meftah, A.; Assmann, W.; Khalfaoui, N.; Stoquert, J.P.; Studer, F.; Toulemonde, M.; Trautmann, C.; Voss, K.-O. Electronic Sputtering of Gd3Ga5O12 and Y3Fe5O12 Garnets: Yield, Stoichiometry and Comparison to Track Formation. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2011, 269, 955–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, J.-M.; Miro, S.; Beuneu, F.; Toulemonde, M. Swift Heavy Ion-Beam Induced Amorphization and Recrystallization of Yttrium Iron Garnet. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2015, 27, 496001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, J.-M.; Miro, S.; Lelong, G.; Guillaumet, M.; Toulemonde, M. Damage Induced in Garnets by Heavy-Ion Irradiations: A Study by Optical Spectroscopies. Philos. Mag. 2018, 98, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, N.; Nellis, W.J.; Mashimo, T.; Ramzan, M.; Ahuja, R.; Kaewmaraya, T.; Kimura, T.; Knudson, M.; Miyanishi, K.; Sakawa, Y.; et al. Dynamic Compression of Dense Oxide (Gd3Ga5O12) from 0.4 to 2.6 TPa: Universal Hugoniot of Fluid Metals. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanin, V.M.; Rodnyi, P.A.; Wieczorek, H.; Ronda, C.R. Electron Traps in Gd3Ga3Al2O12:Ce Garnets Doped with Rare-Earth Ions. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2017, 43, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisiecki, R.; Komar, J.; Macalik, B.; Strzęp, A.; Berkowski, M.; Ryba-Romanowski, W. Exploring the Impact of Structure-Sensitive Factors on Luminescence and Absorption of Trivalent Rare Earth Embedded in Disordered Crystal Structures of Gd3Ga5O12-Gd3Al5O12 and Lu2SiO5-Gd2SiO5 Solid Solution Crystals. Low Temp. Phys. 2023, 49, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karipbayev, Z.T.; Aralbayeva, G.M.; Zhalgas, A.T.; Burkanova, K.; Zhunusbekov, A.M.; Manika, I.; Akilbekov, A.; Bakytkyzy, A.; Ubizskii, S.; Sagyndykova, G.E.; et al. Radiation-Induced Disorder and Lattice Relaxation in Gd3Ga5O12 Under Swift Xe Ion Irradiation. Crystals 2025, 15, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorenko, Y.; Zorenko, T.; Voznyak, T.; Mandowski, A.; Xia, Q.; Batentschuk, M.; Friedrich, J. Luminescence of F+ and F centers in Al2O3-Y2O3 oxide compounds. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2010, 15, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, V.; Laguta, V.V.; Maaroos, A.; Makhov, A.; Nikl, M.; Zazubovich, S. Luminescence of F+-type centers in undoped Lu3Al5O12 single crystals. Phys. Status Solidi B 2011, 248, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varney, C.R.; Selim, F.A. Color centers in YAG. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2015, 2, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratova, V.; Skuratov, V.A.; Buzanov, O.A.; Mololkin, A.A.; Kozlova, A.P.; Kotlov, A.; Popov, A.I.; Pankratov, V. Radiation effects in Gd3(Al,Ga)5O12:Ce3+ single crystals induced by swift heavy ions. Opt. Mater. X 2022, 16, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratova, V.; Butikova, J.; Kotlov, A.; Popov, A.I.; Pankratov, V. Influence of swift heavy ions irradiation on optical and luminescence properties of Y3Al5O12 single crystals. Opt. Mater. X 2024, 23, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Song, J.; Qiu, M.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J. Temperature and fluence dependence of the luminescence properties of Ce:YAG single crystals with ion beam-induced luminescence. Radiat. Meas. 2023, 160, 106878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assylbayev, R.; Lushchik, A.; Lushchik, C.; Kudryavtseva, I.; Shablonin, E.; Vasil’chenko, E.; Akilbekov, A.; Zdorovets, M. Structural defects caused by swift ions in fluorite single crystals. Opt. Mater. 2018, 75, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assylbayev, R.; Akilbekov, A.; Dauletbekova, A.; Lushchik, A.; Shablonin, E.; Vasil’chenko, E. Radiation damage caused by swift heavy ions in CaF2 single crystals. Radiat. Meas. 2016, 90, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baubekova, G.; Assylbayev, R.; Feldbach, E.; Krasnikov, A.; Kudryavtseva, I.; Podelinska, A.; Seeman, V.; Shablonin, E.; Vasil’chenko, E.; Lushchik, A. Accumulation of oxygen interstitial-vacancy pairs under irradiation of corundum single crystals with energetic xenon ions. Radiat. Meas. 2024, 179, 107324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assylbayev, R.; Akilbekov, A.; Baubekova, G.; Chernenko, K.; Zdorovetz, M.; Feldbach, E.; Shablonin, E.; Lushchik, A. Defect-related luminescence of MgO single crystals irradiated with swift 132Xe ions. Opt. Mater. 2022, 127, 112308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assylbayev, R.; Tursumbayeva, G.; Baubekova, G.; Karipbayev, Z.T.; Krasnikov, A.; Shablonin, E.; Aralbayeva, G.M.; Smortsova, Y.; Akilbekov, A.; Popov, A.I.; et al. Influence of Energetic Xe132 Ion Irradiation on Optical, Luminescent and Structural Properties of Ce-Doped Y3Al5O12 Single Crystals. Crystals 2025, 15, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uglov, V.V.; Kholad, V.M.; Grinchuk, P.S.; Ivanov, I.A.; Kozlovsky, A.L.; Zdorovets, M.V. Study of the Microstructure and Phase Composition of Ceramics Based on Silicon Carbide Irradiated with Low-Energy Helium Ions. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 2024, 15, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryskulov, A.E.; Ivanov, I.A.; Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Konuhova, M. The effect of residual mechanical stresses and vacancy defects on the diffusion expansion of the damaged layer during irradiation of BeO ceramics. Opt. Mater. X 2024, 24, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglyakov, M.A.; Kudiiarov, V.N.; Laptev, R.S.; Vrublevskii, D.B.; Svyatkin, L.A.; Uglov, V.V.; Ivanov, I.A.; Koloberdin, M.V. Influence of Chromium Coating on Microstructure Changes in Zirconium Alloy E110 Under High-Temperature Hydrogenation and Kr Ion Irradiation. Coatings 2025, 15, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staltsov, M.S.; Chernov, I.I.; Emelyanova, O.V.; Khmelenin, D.N.; Dikov, A.S.; Ivanov, I.A. Microstructure evolution of 18Cr10Ni-Ti-modified steel after heavy ions irradiation. J. Mater. Sci. 2026, 61, 1261–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugene, K.A.; Assylbayev, R.; Baubekova, G.; Kudryavtseva, I.; Kuzovkov, V.N.; Podelinska, A.; Seeman, V.; Shablonin, E.; Lushchik, A. Annealing of Oxygen-Related Frenkel Defects in Corundum Single Crystals Irradiated with Energetic Xenon Ions. Crystals 2025, 15, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.B.; Vanetsev, A.; Mändar, H.; Nagirnyi, V.; Chernenko, K.; Kirm, M. Investigation of Luminescence Properties of Hydrothermally Synthesized Pr3+ Doped BaLuF5 Nanoparticles under Excitation by VUV Photons. Opt. Mater. 2024, 154, 115781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutyak, N.; Nagirnyi, V.; Romet, I.; Deyneko, D.; Spassky, D. Energy Transfer Processes in NASICON-Type Phosphates under Synchrotron Radiation Excitation. Symmetry 2023, 15, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spassky, D.; Voznyak-Levushkina, V.; Arapova, A.; Zadneprovski, B.; Chernenko, K.; Nagirnyi, V. Enhancement of Light Output in ScxY1−xPO4:Eu3+ Solid Solutions. Symmetry 2020, 12, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romet, I.; Tichy-Rács, É.; Lengyel, K.; Feldbach, E.; Kovács, L.; Corradi, G.; Chernenko, K.; Kirm, M.; Spassky, D.; Nagirnyi, V. Interconfigurational d-f Luminescence of Pr3+ Ions in Praseodymium Doped Li6Y(BO3)3 Single Crystals. J. Lumin. 2024, 265, 120216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosiewicz, K.; Szysiak, A.; Tomala, R.; Gołębiewski, P.; Węglarz, H.; Nagirnyi, V.; Kirm, M.; Romet, I.; Buryi, M.; Jary, V.; et al. Energy-Transfer Processes in Nonstoichiometric and Stoichiometric Er3+, Ho3+, Nd3+, Pr3+, and Cr3+-Codoped Ce:YAG Transparent Ceramics: Toward High-Power and Warm-White Laser Diodes and LEDs. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2023, 20, 014047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundacker, S.; Pots, R.H.; Nepomnyashchikh, A.; Radzhabov, E.; Shendrik, R.; Omelkov, S.; Kirm, M.; Acerbi, F.; Capasso, M.; Paternoster, G.; et al. Vacuum Ultraviolet Silicon Photomultipliers Applied to BaF2 Cross Luminescence Detection for High Rate Ultrafast Timing Applications. Phys. Med. Biol. 2021, 66, 114002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaring, J.; Feldbach, E.; Nagirnyi, V.; Omelkov, S.; Vanetsev, A.; Kirm, M. Ultrafast Radiative Relaxation Processes in Multication Cross Luminescence Materials. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2020, 67, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smortsova, Y.; Chukova, O.; Kirm, M.; Nagirnyi, V.; Pankratov, V.; Kataev, A.; Kotlov, A. The P66 time-resolved VUV spectroscopy beamline at PETRA III storage ring of DESY. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2025, 32, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papagelis, K.; Arvanitidis, J.; Vinga, E.; Christofilos, D.; Kourouklis, G.A.; Kimura, H.; Ves, S. Vibrational properties of solid solutions. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 113504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, D.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Quan, C.; Qiao, Y.; Dong, K.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, M.; et al. Growth, Rietveld Refinement, Raman Spectrum and Dislocation of Ca/Mg/Zr-Substituted GGG: A Potential Substrate and Laser Host Material. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 12777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvorotka, I.I.; Sugak, D.; Yakhnevych, U.; Buryy, O.; Włodarczyk, D.; Pieniążek, A.; Zhydachevskyy, Y.; Levintant-Zayonts, N.; Savytskyy, H.; Bonchyk, O.; et al. Investigation of the Interface of Y3Fe5O12/Gd3Ga5O12 Structure Obtained by the Liquid Phase Epitaxy. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2022, 57, 2100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varney, C.R.; Reda, S.M.; Mackay, D.T.; Rowe, M.C.; Selim, F.A. Strong Visible and Near-Infrared Luminescence in Undoped YAG Single Crystals. AIP Adv. 2011, 1, 042170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovskii, A.; Sugak, D.; Melnyk, S.; Potera, P.; Suchocki, A.; Frukacz, Z. Colour Centers in Doped Gd3Ga5O12 and Y3Al5O12 Laser Crystals. J. Alloys Compd. 2000, 300–301, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriichuk, V.A.; Volzhenskaya, L.G.; Zakharko, Y.M.; Zorenko, Y.V. Influence of structure defects upon the luminescence and thermostimulated effects in Gd3Ga5O12 crystals. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 1987, 47, 902–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aralbayeva, G.; Karipbayev, Z.; Zafari, U.; Bakytkyzy, A.; Zhunusbekov, A.; Kumarbekov, K.; Popov, A.I. Modeling Defect States and the Role of 4f Electrons in Gd3Ga5O12 Using DFT Methods. Bull. L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian Natl. Univ. Phys. Astron. Ser. 2025, 152, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirinyan, A.; Bilogorodskyy, Y. Effect of radiation-induced vacancy saturation on the first-order phase transformation in nanoparticles: Insights from a model. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2024, 15, 1453–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotomin, E.; Kuzovkov, V. Radiation-induced aggregatization of immobile defects. Solid State Commun. 1981, 39, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzovkov, V.N.; Kotomin, E.A. The kinetics of defect accumulation under irradiation: Many-particle effects. Phys. Scr. 1993, 47, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, W.A. Radiation processes in halide crystals and glasses. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 1988, 32, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonder, E.; Sibley, W.A.; Rowe, J.E.; Nelson, C.M. Some properties of defects produced by ionizing radiation in KCl between 80 and 300° K. Phys. Rev. 1967, 153, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushchik, A.; Podelinska, A.; Seeman, V.; Shablonin, E.; Kotomin, E.A.; Kuzovkov, V.N. Open questions on the thermal stability of primary electronic centers in irradiated MgO single crystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 2775–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.V.; Webster, P.T.; Woller, K.B.; Morath, C.P.; Short, M.P. Understanding the fundamental driver of semiconductor radiation tolerance with experiment and theory. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2022, 6, 084601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Raman Modes | This Work | Unirradiated Sample [37] | Au 12 MeV, [38] | Neutron Irradiated [30] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine Sample | F = 1013 ion/cm2 | F = 5 × 1013 ion/cm2 | F = 1014 ion/cm2 | ||||||||||

| ν, cm−1 | FWHM, cm−1 | ν, cm−1 | FWHM, cm−1 | ν, cm−1 | FWHM, cm−1 | ν, cm−1 | FWHM, cm−1 | F = 3 × 1014 | F = 1016 n/cm2 | F = 1018 n/cm2 | |||

| 1 | Eg | 112.3 | 3.9 | 112.2 | 3.5 | 112.0 | 4.0 | 112.4 | 0.0 | 110.0 | 110.9 | 111.5 | 110.6 |

| 2 | T2g | 170.6 | 4.5 | 170.6 | 4.2 | 170.4 | 4.7 | 170.2 | 1.4 | 170.0 | 171.9 | 169.7 | 169.6 |

| 3 | T2g | 180.6 | 4.3 | 180.6 | 4.2 | 180.5 | 4.5 | 180.3 | 1.5 | 180.0 | 180.2 | 179.3 | 179.4 |

| 4 | T2g | 239.9 | 4.2 | 239.9 | 4.1 | 239.9 | 4.3 | 239.6 | 1.5 | 239.0 | 241.3 | 239.0 | 238.4 |

| 5 | Eg | 261.3 | 3.3 | 261.4 | 3.2 | 261.3 | 2.7 | 260.7 | 1.2 | 261.0 | 260.3 | 260.7 | 260.2 |

| 6 | T2g | 274.1 | 6.2 | 274.0 | 5.6 | 274.0 | 6.0 | 274.0 | 2.1 | 273.0 | 274.6 | 273.5 | 273.1 |

| 7 | A1g | 354.8 | 10.9 | 354.7 | 11.1 | 354.6 | 11.2 | 355.3 | 3.7 | 353.0 | 353.5 | 353.9 | 354.8 |

| 8 | T2g | 382.0 | 6.5 | 381.8 | 5.9 | 382.0 | 6.4 | 380.9 | 3.5 | 381.0 | 380.0 | 379.8 | 379.5 |

| 9 | T2g | 524.6 | 10.8 | 524.6 | 9.5 | 524.4 | 10.4 | 524.8 | 3.4 | 524.0 | 525.6 | 524.6 | 523.8 |

| 10 | A1g | 582.9 | 10.1 | 583.2 | 9.7 | 582.9 | 9.9 | 583.0 | 3.6 | 583.0 | 585.4 | 584.1 | 582.9 |

| 11 | T2g | 598.3 | 12.9 | 598.3 | 11.9 | 598.4 | 12.6 | 599.1 | 3.8 | 598.0 | 596.2 | 598.6 | 598.4 |

| 12 | T2g | 740.6 | 16.9 | 740.5 | 15.8 | 740.3 | 16.2 | 741.5 | 5.3 | 740.0 | 740.8 | 741.6 | 741.2 |

| 13 | T2g | 888.3 | 12.3 | 888.0 | 11.8 | 888.3 | 12.3 | 887.5 | 3.5 | 858/896 | 896.1 | – | – |

| Fluence, ion/cm2 | E1, eV | ΔE, eV | E2, eV | ΔE, eV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine | 2.40 | 0.75 | ||

| 1011 | 2.44 | 1.00 | 2.75 | 0.12 |

| 1012 | 2.44 | 1.00 | 2.75 | 0.15 |

| 1013 | 2.42 | 0.89 | 2.78 | 0.28 |

| 1014 | 2.41 | 0.92 | 2.74 | 0.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Karipbayev, Z.T.; Aralbayeva, G.M.; Kumarbekov, K.K.; Kakimov, A.B.; Zhunusbekov, A.M.; Akilbekov, A.; Brik, M.G.; Konuhova, M.; Ubizskii, S.; Smortsova, Y.; et al. Effects of 147 MeV Kr Ions on the Structural, Optical and Luminescent Properties of Gd3Ga5O12. Crystals 2026, 16, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010040

Karipbayev ZT, Aralbayeva GM, Kumarbekov KK, Kakimov AB, Zhunusbekov AM, Akilbekov A, Brik MG, Konuhova M, Ubizskii S, Smortsova Y, et al. Effects of 147 MeV Kr Ions on the Structural, Optical and Luminescent Properties of Gd3Ga5O12. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaripbayev, Zhakyp T., Gulnara M. Aralbayeva, Kuat K. Kumarbekov, Askhat B. Kakimov, Amangeldy M. Zhunusbekov, Abdirash Akilbekov, Mikhail G. Brik, Marina Konuhova, Sergii Ubizskii, Yevheniia Smortsova, and et al. 2026. "Effects of 147 MeV Kr Ions on the Structural, Optical and Luminescent Properties of Gd3Ga5O12" Crystals 16, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010040

APA StyleKaripbayev, Z. T., Aralbayeva, G. M., Kumarbekov, K. K., Kakimov, A. B., Zhunusbekov, A. M., Akilbekov, A., Brik, M. G., Konuhova, M., Ubizskii, S., Smortsova, Y., Suchikova, Y., Djurković, S., Piskunov, S., & Popov, A. I. (2026). Effects of 147 MeV Kr Ions on the Structural, Optical and Luminescent Properties of Gd3Ga5O12. Crystals, 16(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010040