Electrodeposition of Copper–Nickel Foams: From Separate Phases to Solid Solution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Electrodeposition

- 75 mM CuSO4 (puriss., Component-Reaktiv, Moscow, Russia), 200 mM NiSO4 (puriss., Component-Reaktiv, Moscow, Russia), 50 mM KCl (puriss. spec., Component-Reaktiv, Moscow, Russia), 0.5 M H2SO4 (puriss. spec., Component-Reaktiv, Moscow, Russia), 30 g·L−1 H3BO3 (puriss. spec., Component-Reaktiv, Moscow, Russia);

- 0.3 M sodium citrate (puriss., Component-Reaktiv, Moscow, Russia), 1 M (NH4)2SO4 (p.a., Component-Reaktiv, Moscow, Russia), 80 mM CuSO4, 175 mM NiSO4;

- 0.3 M sodium citrate, 1 M (NH4)2SO4, 125 mM CuSO4, 125 mM NiSO4;

- 0.3 M sodium citrate, 1 M (NH4)2SO4, 175 mM CuSO4, 80 mM NiSO4.

2.2. Copper–Nickel Foam Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

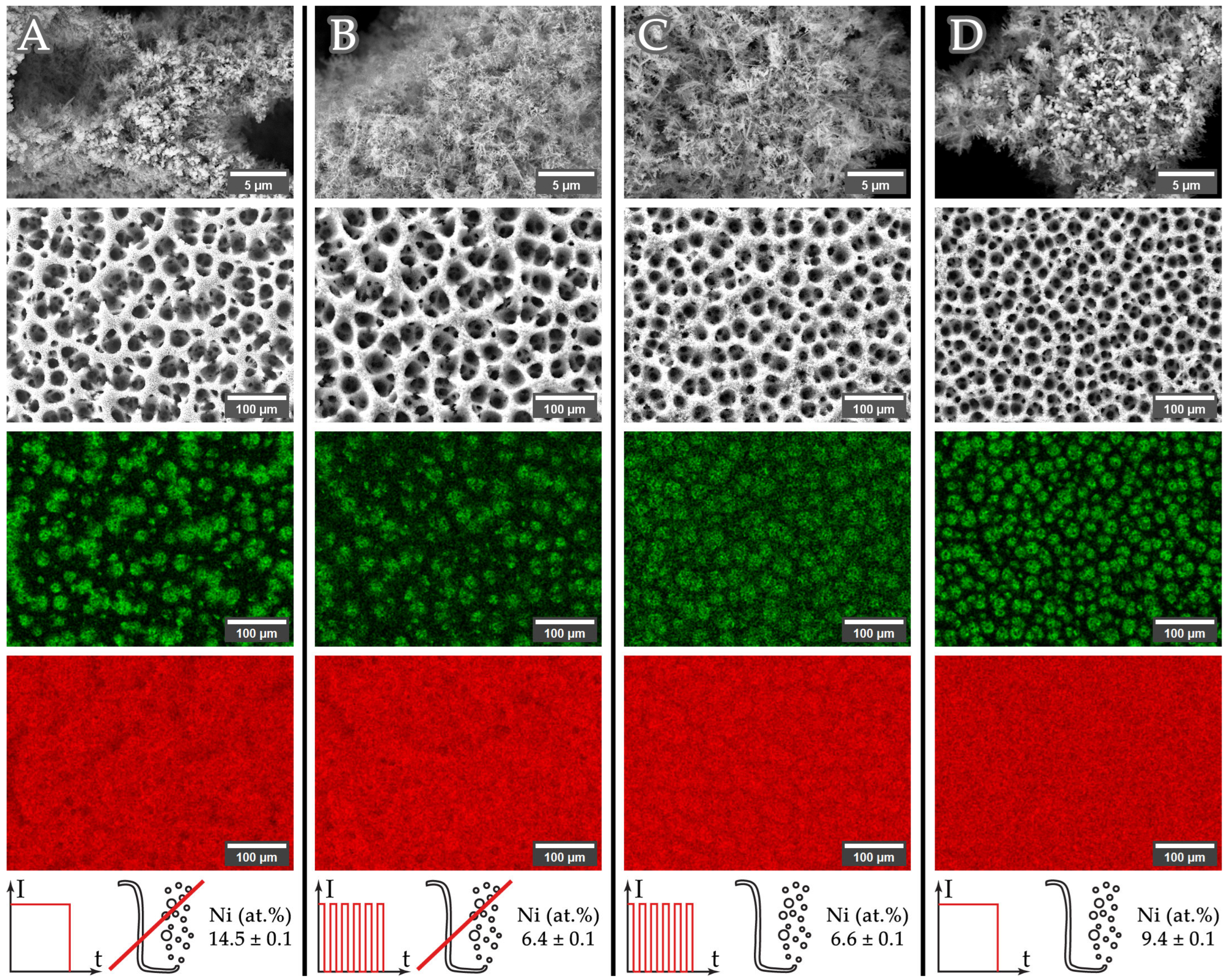

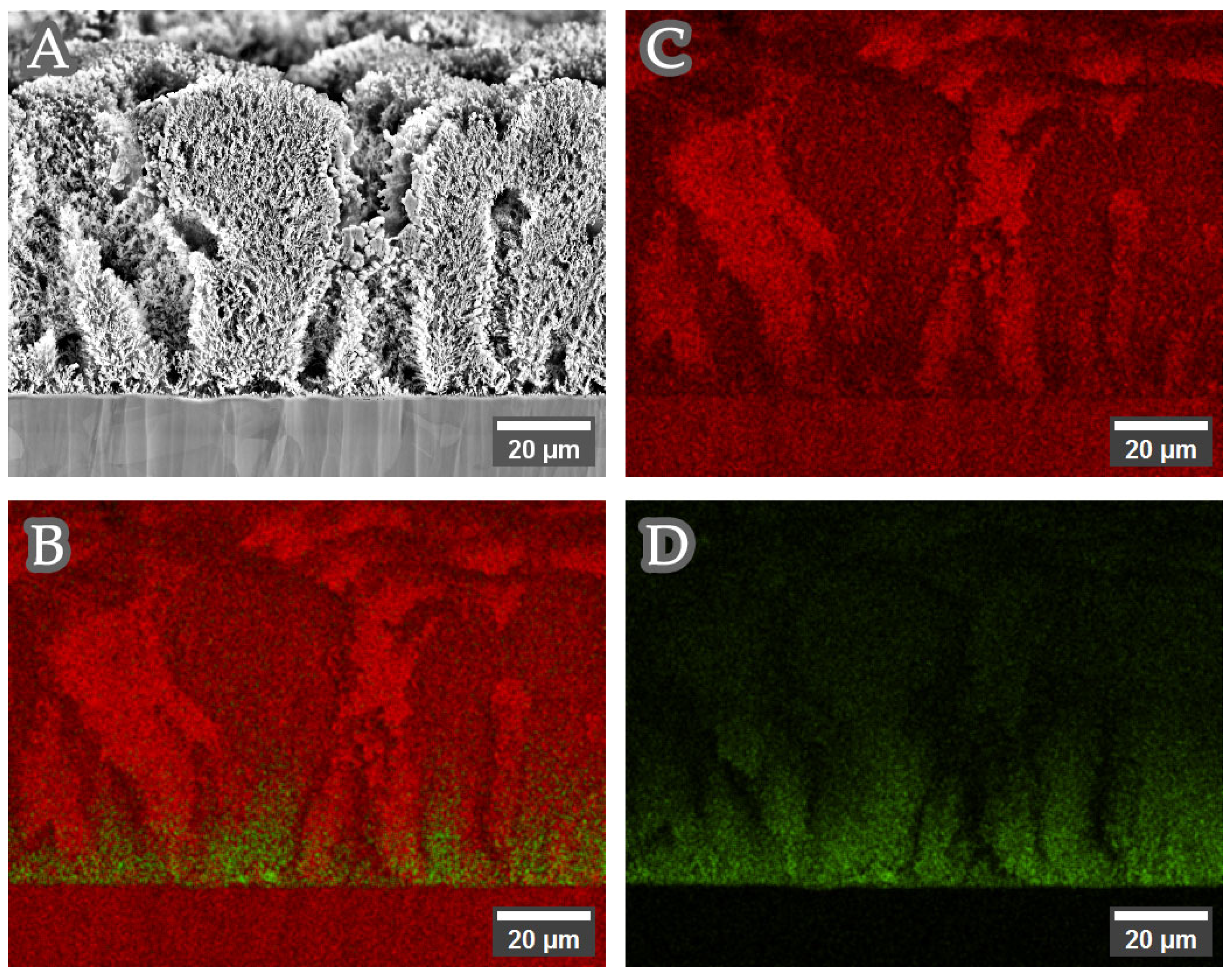

3.1. Structure, Morphology and Composition of Copper–Nickel Foams: Solution 1 (Complex Agent Free, Sulfate)

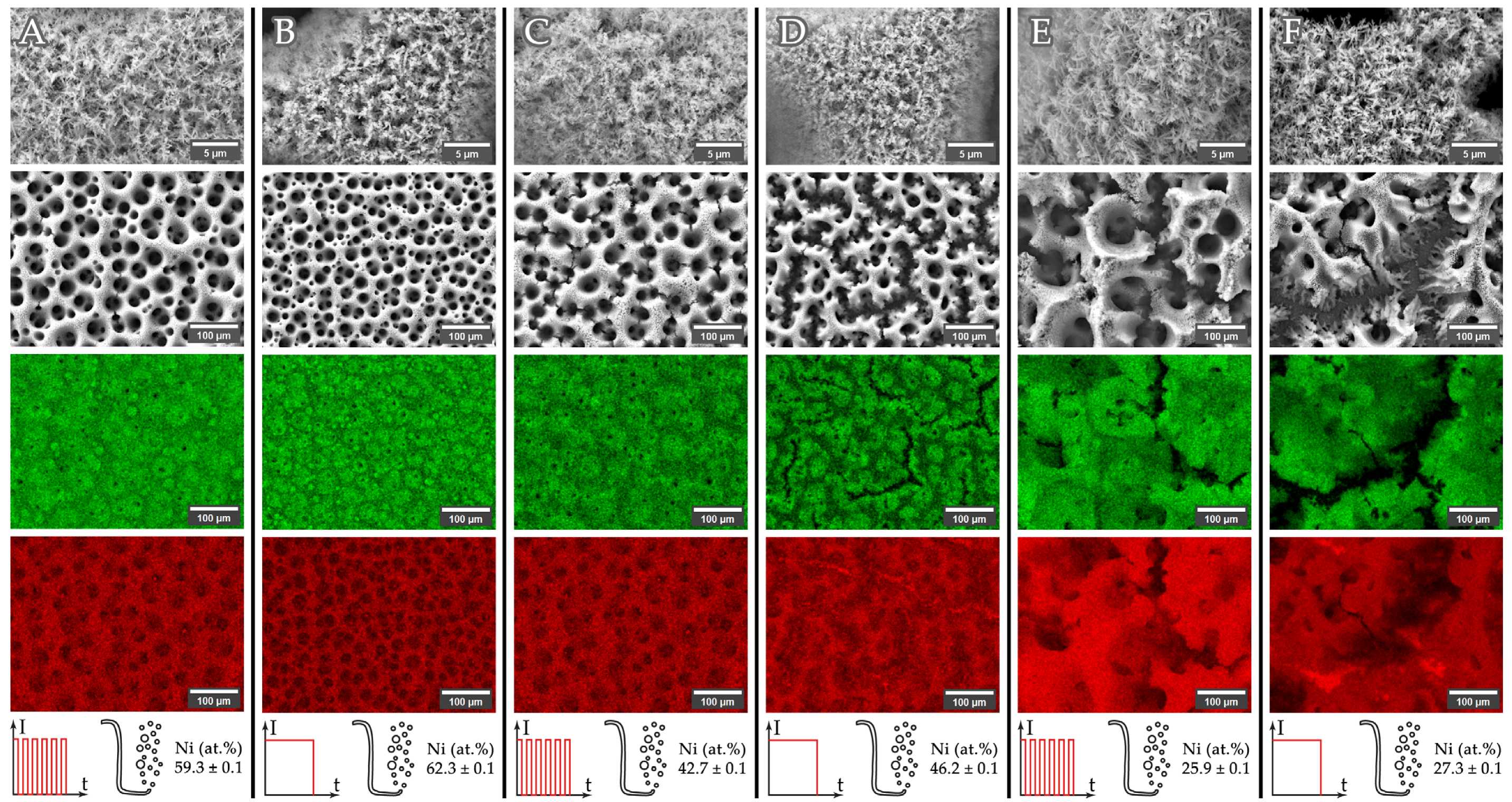

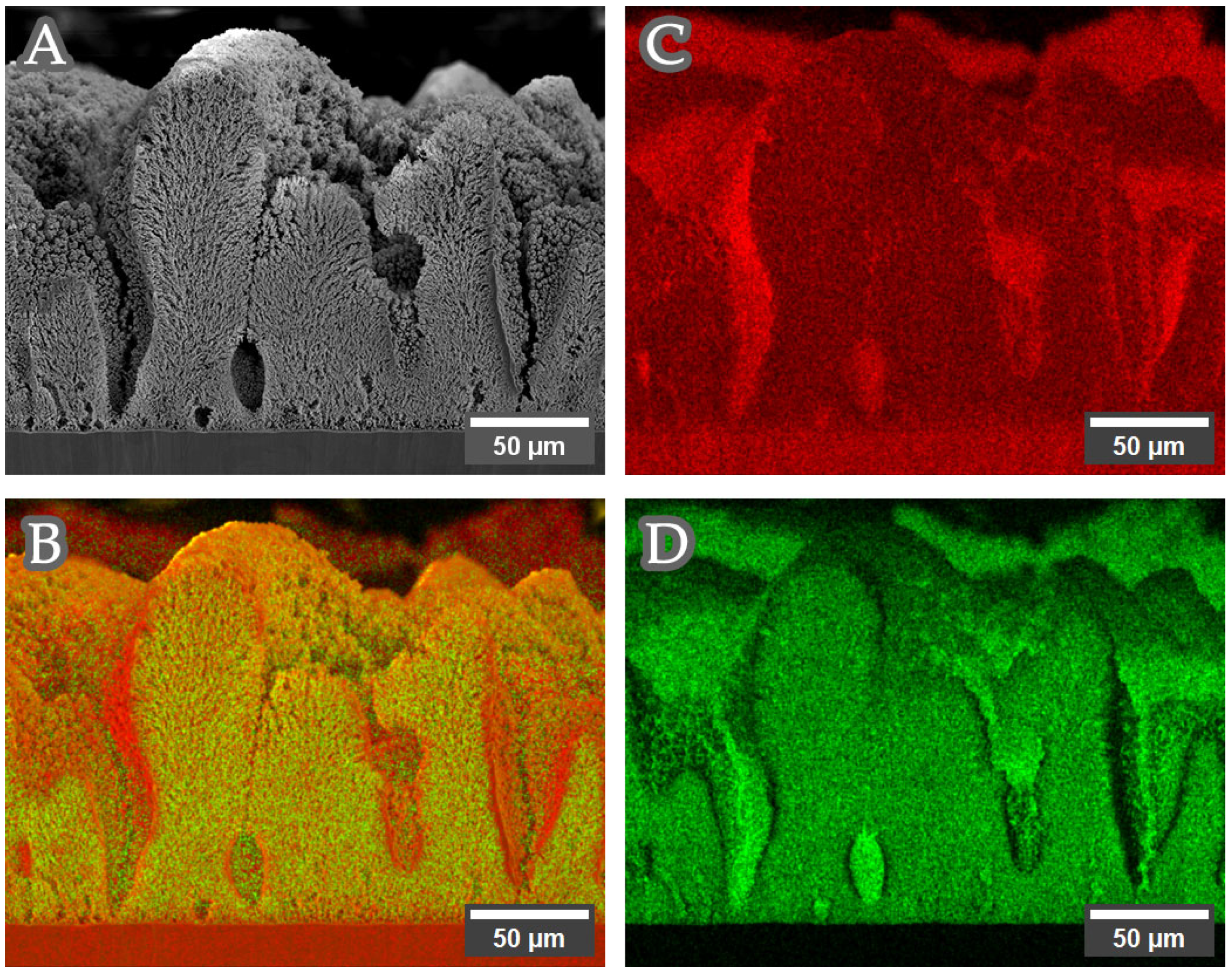

3.2. Structure, Morphology and Composition of Copper–Nickel Foams: Solutions 2–4 (With Complexing Agent, Citrate-Based)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lahiri, A.; Endres, F. Review—Electrodeposition of Nanostructured Materials from Aqueous, Organic and Ionic Liquid Electrolytes for Li-Ion and Na-Ion Batteries: A Comparative Review. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, D597–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, E.C.; Zach, M.P.; Favier, F.; Murray, B.J.; Inazu, K.; Hemminger, J.C.; Penner, R.M. Metal nanowire arrays by electrodeposition. ChemPhysChem 2003, 4, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal Lopez, M.; Ustarroz, J. Electrodeposition of nanostructured catalysts for electrochemical energy conversion: Current trends and innovative strategies. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2021, 27, 100688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Yang, J.W.; Choi, S.; Jang, H.W. Nanoscale electrodeposition: Dimension control and 3D conformality. Exploration 2021, 1, 20210012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, M.B.; Borse, R.A.; Gomaa Abdelkader Mohamed, A.; Wang, Y. Electrocatalysts by Electrodeposition: Recent Advances, Synthesis Methods, and Applications in Energy Conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2101313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Deka, S. Focused Review on the Use of Bimetallic Alloy Nanoparticle Electrocatalysts in Water Splitting Reactions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 19037–19054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhafola, M.D.; Balogun, S.A.; Modibane, K.D. A Comprehensive Review of Bimetallic Nanoparticle–Graphene Oxide and Bimetallic Nanoparticle–Metal–Organic Framework Nanocomposites as Photo-, Electro-, and Photoelectrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Energies 2024, 17, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Hutchings, G.S.; Yu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Forest, R.V.; Tao, R.; Rosen, J.; Yonemoto, B.T.; Cao, Z.; Zheng, H.; et al. Highly porous non-precious bimetallic electrocatalysts for efficient hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Vasileff, A.; Jiao, Y.; Chen, S.; Song, L.; Zheng, B.; Zheng, Y.; Qiao, S.-Z. Strain Effect in Bimetallic Electrocatalysts in the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yu, H.; Feng, T.; Zhao, D.; Piao, J.; Lei, J. Surface Roughed and Pt-Rich Bimetallic Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Balčiūnaitė, A.; Upskuvienė, D.; Vaičiūnienė, J.; Tamašauskaitė-Tamašiūnaitė, L.; Norkus, E. Bimetallic Ni–Mn Electrocatalysts for Stable Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Simulated/Alkaline Seawater and Overall Performance in the Splitting of Alkaline Seawater. Coatings 2024, 14, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Shu, Y.; Li, F.; Peng, G. Bimetallic catalysts as electrocatalytic cathode materials for the oxygen reduction reaction in microbial fuel cell: A review. Green Energy Environ. 2023, 8, 1043–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero-Escribano, M.; Jensen, K.D.; Jensen, A.W. Recent advances in bimetallic electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction: Design principles, structure-function relations and active phase elucidation. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2018, 8, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.W.; Yang, H.L.; Wang, Y.X.; Dou, S.X.; Liu, H.K. A Comprehensive Review on Controlling Surface Composition of Pt-Based Bimetallic Electrocatalysts. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bampos, G.; Bebelis, S. Pd-Based Bimetallic Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Oxidation Reaction in 0.1 M KOH Solution. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, V.; Alekseenko, A.; Belenov, S.; Menshikov, V.; Moguchikh, E.; Novomlinskaya, I.; Paperzh, K.; Pankov, I. Exploring the Potential of Bimetallic PtPd/C Cathode Catalysts to Enhance the Performance of PEM Fuel Cells. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Tackett, B.M.; Chen, J.G.; Jiao, F. Bimetallic Electrocatalysts for CO2 Reduction. Top. Curr. Chem. 2018, 376, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chuai, H.; Meng, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; Ma, X. Copper-based bimetallic electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction: From mechanism understandings to product regulations. Mater. Rep. Energy 2023, 3, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Liu, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, R.; Yin, Z. Perspectives on Cu–Ag Bimetallic Catalysts for Electrochemical CO2 Reduction Reaction: A Mini-Review. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 5659–5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, C. Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction over Bimetallic Bi-Based Catalysts: A Review. CCS Chem. 2023, 5, 544–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, S.; Wang, Y.; Tan, J.; Ma, L.; Wang, T.; Xia, Y. Surface Structure Engineering of PdAg Alloys with Boosted CO2 Electrochemical Reduction Performance. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattarozzi, L.; Cattarin, S.; Comisso, N.; Gerbasi, R.; Guerriero, P.; Musiani, M.; Vazquez-Gomez, L.; Verlato, E. Electrodeposition of Cu-Ni Alloy Electrodes with Bimodal Porosity and Their Use for Nitrate Reduction. ECS Electrochem. Lett. 2013, 2, D58–D60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Li, X.; Ding, L.; Qu, Y.; Chang, X. Artificial Cu-Ni catalyst towards highly efficient nitrate-to-ammonia conversion. Sci. China Mater. 2023, 66, 2329–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despić, A.R.; Jović, V.D. Electrochemical Deposition and Dissolution of Alloys and Metal Composites—Fundamental Aspects. In Modern Aspects of Electrochemistry; White, R.E., Bockris, J.O.M., Conway, B.E., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; Volume 27, pp. 143–232. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, P.; Neuschütz, D. Binary systems. Part 3: Binary Systems from Cs-K to Mg-Zr·Cu-Ni. In Landolt-Börnstein—Group IV Physical Chemistry; Binary Systems. Part 3: Binary Systems from Cs-K to Mg-Zr; Franke, P., Neuschütz, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 19B3. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Yu, J.; Meng, J.; Xu, C.; Cai, J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Y.; Yu, D.; Zhou, X.; Chen, C. Porous Ni-Cu Alloy Dendrite Anode Catalysts with High Activity and Selectivity for Direct Borohydride Fuel Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 3910–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modghan, N.-S.; Mirjalili, M.; Moayed, M.-H.; Darband, G.B. A Suitable Porous Micro/Nanostructured Cu and Cu–Ni Film: Evaluation of Electrodeposition Behavior, Electrocatalytic Activity, and Surface Characterization of Porous Film. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 076506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, T.; Zhu, Q.; Fu, J.; Peng, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, S. Three-dimensional Nanoporous Cu-Doped Ni Coating as Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Hydrazine Sensing and Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 305502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bai, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Fan, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Guan, R. A Comparison between Porous to Fully Dense Electrodeposited CuNi Films: Insights on Electrochemical Performance. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negem, M.; Nady, H.; Dunnill, C.W. Nanocrystalline Ni–Cu Electroplated Alloys Cathodes for Hydrogen Generation in Phosphate-Buffered Neutral Electrolytes. J. Bio-Tribo-Corros. 2020, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, J.; Chen, R.; Wu, L.; Shi, J.; Luo, J. Bimetallic Cu–Zn Catalysts for Electrochemical CO2 Reduction: Phase-Separated versus Core–Shell Distribution. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 2741–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.S.; Timoshenko, J.; Scholten, F.; Sinev, I.; Herzog, A.; Haase, F.T.; Roldan Cuenya, B. Operando Insight into the Correlation between the Structure and Composition of CuZn Nanoparticles and Their Selectivity for the Electrochemical CO2 Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 19879–19887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, D.; Ang, B.S.-H.; Yeo, B.S. Tuning the Selectivity of Carbon Dioxide Electroreduction toward Ethanol on Oxide-Derived CuxZn Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 8239–8247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Pan, X.; Shen, H.; Yu, J.; Guo, T.; Wang, Y. Role of electrons and H* in electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonium for CuNi alloy. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 54, 105308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Tan, Y.C.; Kim, B.; Ringe, S.; Oh, J. Tunable Product Selectivity in Electrochemical CO2 Reduction on Well-Mixed Ni-Cu Alloys. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 55272–55280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Cao, S.; Li, Q.; Chen, C.; Yuan, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Yang, J.; et al. Selective CO2 reduction to CH3OH over atomic dual-metal sites embedded in a metal-organic framework with high-energy radiation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.-C.; Liu, M. Copper Foam Structures with Highly Porous Nanostructured Walls. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 5460–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, N.D.; Pavlović, L.J.; Pavlović, M.G.; Popov, K.I. Formation of dish-like holes and a channel structure in electrodeposition of copper under hydrogen co-deposition. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 52, 8096–8104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.A.; Russell, A.E.; Roy, S. The Development of a Stable Citrate Electrolyte for the Electrodeposition of Copper-Nickel Alloys. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1998, 145, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, H.M. A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1969, 2, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.J.; Howard, C.J. Quantitative phase analysis from neutron powder diffraction data using the Rietveld method. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1987, 20, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyov, L.A. Full-profile refinement by derivative difference minimization. J. Appl. Crystallogr. Erratum in J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2005, 38, 401. https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889805004899.. 2004, 37, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuiderveld, K. VIII.5. Contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization. In Graphics Gems IV; Heckbert, P.S., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 474–485. [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromey, D.W. Avoiding twisted pixels: Ethical guidelines for the appropriate use and manipulation of scientific digital images. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2010, 16, 639–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbury, D.E.; Ritchie, N.W. Performing elemental microanalysis with high accuracy and high precision by scanning electron microscopy/silicon drift detector energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (SEM/SDD-EDS). J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 493–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bari, G.A. Electrodeposition of Nickel. In Modern Electroplating, 5th ed.; Schlesinger, M., Paunovic, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Saraby-Reintjes, A.; Fleischmann, M. Kinetics of electrodeposition of nickel from Watts baths. Electrochim. Acta 1984, 29, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulis, J.; Sližys, R. On some characteristics of cathodic processes in nickel electrodeposition. Electrochim. Acta 1964, 9, 1177–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.C.O.; Koper, M.T.M. Measuring local pH in electrochemistry. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2021, 25, 100649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, J. The Structures of the Elements; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1974; p. 436. [Google Scholar]

- Cline, J.P.; Mendenhall, M.H.; Black, D.; Windover, D.; Henins, A. The Optics and Alignment of the Divergent Beam Laboratory X-ray Powder Diffractometer and its Calibration Using NIST Standard Reference Materials. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2015, 120, 173–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugénio, S.; Silva, T.M.; Carmezim, M.J.; Duarte, R.G.; Montemor, M.F. Electrodeposition and characterization of nickel–copper metallic foams for application as electrodes for supercapacitors. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2013, 44, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.A. Introduction to the Rietveld method. In The Rietveld Method; Young, R.A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R.; Snyder, R.L. Chapter 7. Instruments for the measurement of powder patterns. In Introduction to X-Ray Powder Diffractometry; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, E.E.; Morozov, D.A.; Frolov, V.V.; Arkharova, N.A.; Khmelenin, D.N.; Antipov, E.V.; Nikitina, V.A. Roughness Factors of Electrodeposited Nanostructured Copper Foams. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, A.R.; Wilson, A.J.C. The diffraction of X rays by distorted crystal aggregates—I. Proc. Phys. Soc. 1944, 56, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungár, T.; Dragomir, I.; Révész, Á.; Borbély, A. The contrast factors of dislocations in cubic crystals: The dislocation model of strain anisotropy in practice. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1999, 32, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despic, A.R.; Jović, V.D. Formation of Metallic Materials of Desired Structure and Properties by Electrochemical Deposition. Mater. Sci. Forum 1996, 214, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, W.M.; Lide, D.R.; Bruno, T.J. (Eds.) CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 97th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; p. 2670. [Google Scholar]

- Rode, S.; Henninot, C.; Vallières, C.; Matlosz, M. Complexation Chemistry in Copper Plating from Citrate Baths. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2004, 151, C405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, S.; Henninot, C.; Matlosz, M. Complexation Chemistry in Nickel and Copper-Nickel Alloy Plating from Citrate Baths. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, C248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkh, O.; Burstein, L.; Shacham-Diamand, Y.; Gileadi, E. The Chemical and Electrochemical Activity of Citrate on Pt Electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, F85–F91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, M. Diffraction analysis of layer disorder. Z. Kristallogr. 2008, 223, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyerlein, K.R.; Snyder, R.L.; Scardi, P. Faulting in finite face-centered-cubic crystallites. Acta Crystallogr. A 2011, 67, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardi, P.; Leoni, M. Whole powder pattern modelling. Acta Crystallogr. A 2002, 58, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

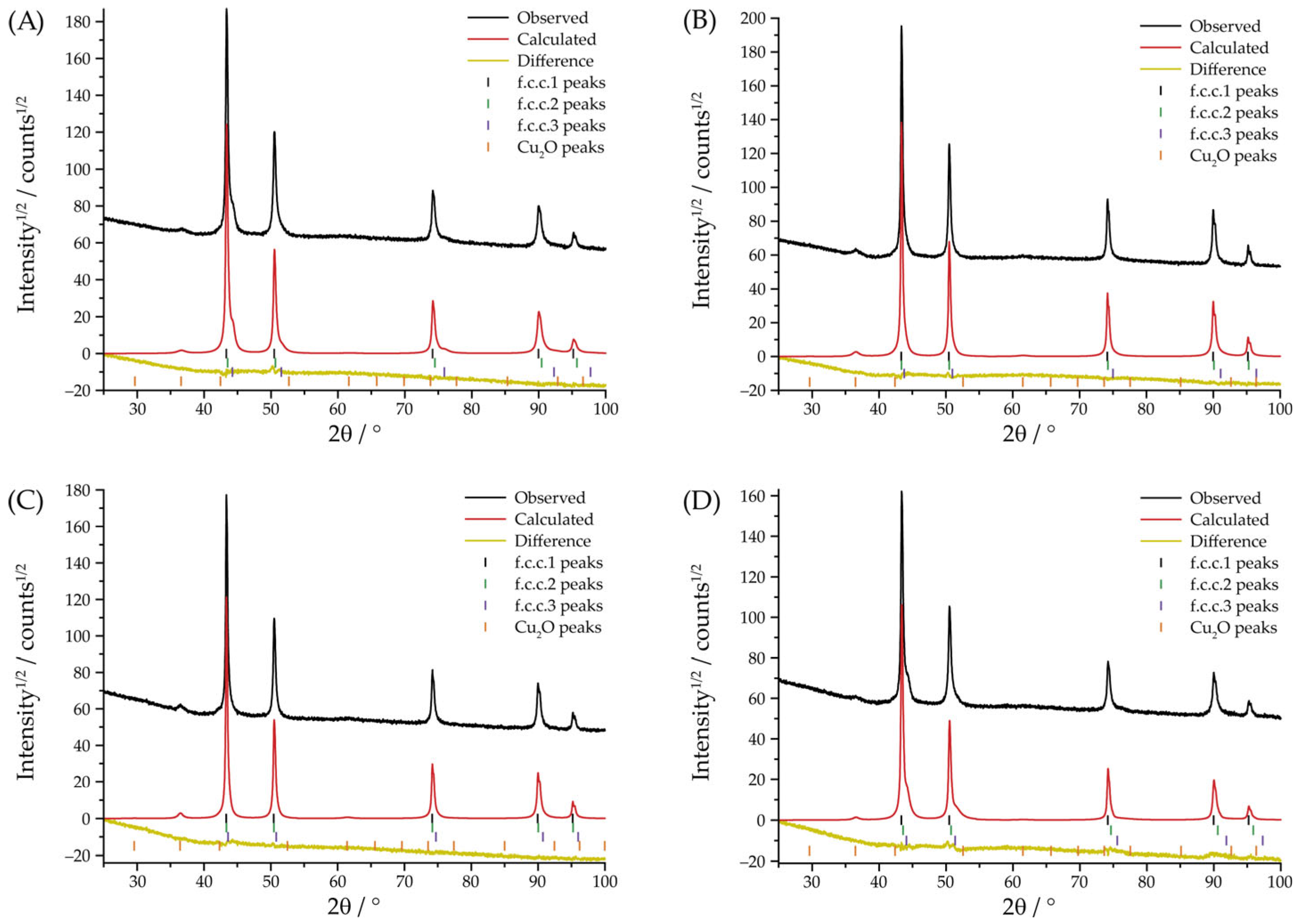

| Current | Intermittent | Agitated | Phase Composition (wt.%) | Ni XRD (at. %) 1 | Ni XRF (at. %) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 A | No | No | f.c.c.1: 63.9 ± 4.7 (a = 3.6138(1) Å) | 17 ± 9 | 14.5 ± 0.1 |

| f.c.c.2: 17.9 ± 6.2 (a = 3.596(4) Å) | |||||

| f.c.c.3: 15.4 ± 1.9 (a = 3.543(1) Å) | |||||

| Cu2O: 2.8 ± 0.4 | |||||

| 3 A | Yes | No | f.c.c.1: 33.0 ± 1.0 (a = 3.6142(1) Å) | 8 ± 1 | 6.4 ± 0.1 |

| f.c.c.2: 50.7 ± 0.9 (a = 3.6103(3) Å) | |||||

| f.c.c.3: 12.0 ± 0.9 (a = 3.578(4) Å) | |||||

| Cu2O: 4.3 ± 0.1 | |||||

| 3 A | Yes | Yes | f.c.c.1: 12.2 ± 1.5 (a = 3.6144(1) Å) | 5 ± 1 | 6.6 ± 0.1 |

| f.c.c.2: 72.3 ± 1.6 (a = 3.6123(2) Å) | |||||

| f.c.c.3: 11.2 ± 1.4 (a = 3.590(4) Å) | |||||

| Cu2O: 4.3 ± 0.3 | |||||

| 3 A | No | Yes | f.c.c.1: 56.0 ± 1.3 (a = 3.6134(2) Å) | 27 ± 7 | 9.4 ± 0.1 |

| f.c.c.2: 5.5 ± 0.5 (a = 3.593(1) Å) | |||||

| f.c.c.3: 36.7 ± 5.2 (a = 3.554(2) Å) | |||||

| Cu2O: 1.9 ± 0.3 |

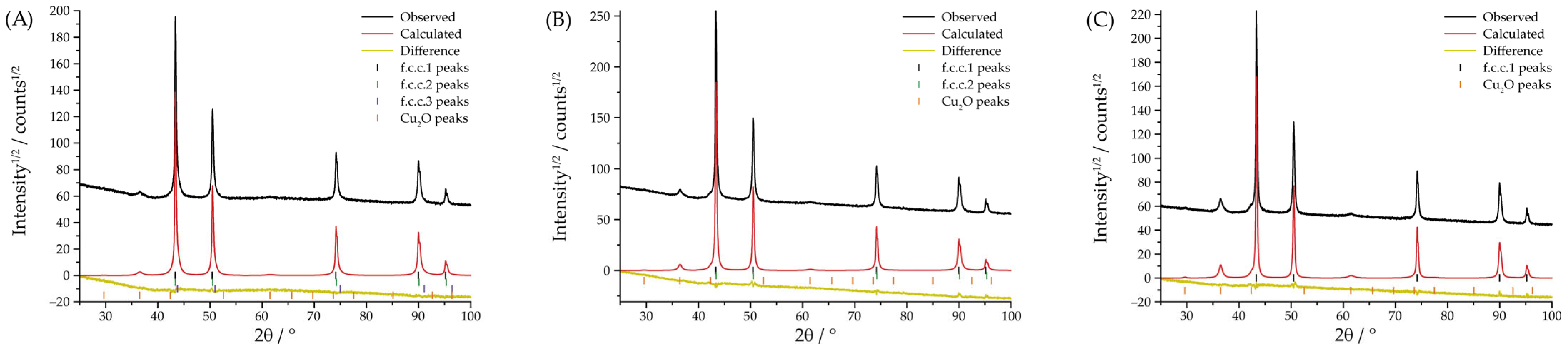

| Current | Intermittent | Agitated | Phase Composition (wt.%) | Ni XRD (at. %) 1 | Ni XRF (at. %) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 A | Yes | No | f.c.c.1: 33.0 ± 1.0 (a = 3.6142(1) Å) | 8 ± 1 | 6.4 ± 0.1 |

| f.c.c.2: 50.7 ± 0.9 (a = 3.6103(3) Å) | |||||

| f.c.c.3: 12.0 ± 0.9 (a = 3.578(4) Å) | |||||

| Cu2O: 4.3 ± 0.1 | |||||

| 2 A | Yes | No | f.c.c.1: 58.8 ± 2.9 (a = 3.6137(2) Å) | 3 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

| f.c.c.2: 35.9 ± 2.8 (a = 3.6090(6) Å) | |||||

| Cu2O: 5.3 ± 0.2 | |||||

| 1 A | Yes | No | f.c.c.1: 89.4 ± 0.5 (a = 3.6139(2) Å) | 1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| Cu2O: 10.6 ± 0.4 |

| Solution | Intermitted | Agitated | Phase Composition (wt.%) | Ni XRD (at. %) 1 | Ni XRF (at. %) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Yes | Yes | f.c.c.1: 12.7 ± 0.5% (a = 3.583(2) Å) | 70 ± 14 | 59.3 ± 0.1 |

| f.c.c.2: 65.0 ± 2.4 (a = 3.550(1) Å) | |||||

| f.c.c.3: 22.3 ± 2.8 (a = 3.535(3) Å) | |||||

| 2 | No | Yes | f.c.c.1: 53.2 ± 1.8 (a = 3.565(1) Å) | 67 ± 5 | 62.3 ± 0.1 |

| f.c.c.2: 46.8 ± 1.5 (a = 3.541(1) Å) | |||||

| 3 | Yes | Yes | f.c.c.1: 99.5 ± 2.6 (a = 3.5716(9) Å) | 47 ± 1 | 42.7 ± 0.1 |

| Cu2O: 0.5 ± 0.1 | |||||

| 3 | No | Yes | f.c.c.1: 76.6 ± 2.8 (a = 3.595(1) Å) | 28 ± 6 | 46.2 ± 0.1 |

| f.c.c.2: 22.6 ± 2.1 (a = 3.570(3) Å) | |||||

| Cu2O: 0.8 ± 0.1 | |||||

| 4 | Yes | Yes | f.c.c.1: 96.9 ± 2.1 (a = 3.5944(6) Å) | 22 ± 0.5 | 25.9 ± 0.1 |

| Cu2O: 3.1 ± 0.1 | |||||

| 4 | No | Yes | f.c.c.1: 96.8 ± 1.7 (a = 3.6044(6) Å) | 11 ± 0.2 | 27.3 ± 0.1 |

| Cu2O: 3.2 ± 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Levin, E.E.; Chertkova, V.P.; Arkharova, N.A. Electrodeposition of Copper–Nickel Foams: From Separate Phases to Solid Solution. Crystals 2026, 16, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010020

Levin EE, Chertkova VP, Arkharova NA. Electrodeposition of Copper–Nickel Foams: From Separate Phases to Solid Solution. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevin, Eduard E., Victoria P. Chertkova, and Natalia A. Arkharova. 2026. "Electrodeposition of Copper–Nickel Foams: From Separate Phases to Solid Solution" Crystals 16, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010020

APA StyleLevin, E. E., Chertkova, V. P., & Arkharova, N. A. (2026). Electrodeposition of Copper–Nickel Foams: From Separate Phases to Solid Solution. Crystals, 16(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010020