Abstract

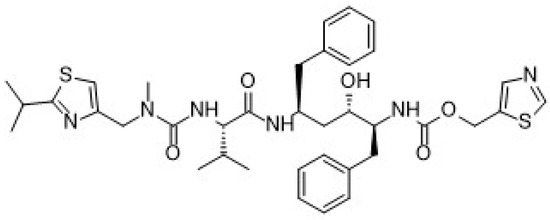

The control of crystal polymorphs is central to the design of pharmaceuticals and functional materials. Conventionally, crystal polymorph production has been controlled primarily by adjusting chemical and thermodynamic parameters. In this study, we developed a device capable of emitting infrared radiation at selected wavelengths using a novel material having a “MIM structure” which is a type of metamaterial. With this device, we propose a new approach to crystal polymorph control through the irradiation of narrow-band infrared radiation that coincides with the infrared absorption band of specific functional groups. In this paper, we present the design and operating principle of a new crystallization system, and as an application example, we report the experimental results of controlling the crystal polymorphs of Ritonavir, an active pharmaceutical ingredient.

1. Introduction

The control of crystal polymorphs is central to the design of pharmaceuticals [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] and functional materials [10,11,12,13,14]. It is of particular importance in the pharmaceutical field in that, as generally known, differences among crystal polymorphs of the same compound can significantly affect the solubility, stability, absorption, and bioavailability of the compound. Polymorph control is fundamental to the stability of drug efficacy and to formulation development. Crystal polymorphs also represent a key aspect of patent strategies and quality assurance systems, making them critically important for research and development by pharmaceutical companies. Conventionally, crystal polymorph production has been controlled primarily by adjusting chemical and thermodynamic parameters, such as solvent selection, temperature control, cooling rate, and recrystallization method [15,16,17].

Optical control and applied physics have recently seen dramatic progress in research on metamaterials—materials with metal micro-pattern structures on the scale of wavelengths of light or smaller. In this study, we developed a device capable of emitting infrared radiation at selected wavelengths using a novel material having a Metal-Insulator-Metal (MIM) layered structure, which is a type of metamaterial. With this device, we propose a new approach to crystal polymorph control through the irradiation of narrow-band infrared radiation that coincides with the infrared absorption band of specific functional groups.

During crystallization, low- to medium-molecular-weight organic compounds such as active pharmaceutical ingredients form aggregates through various intermolecular interactions or forces, such as the van der Waals force, hydrogen bonds, and π-π interactions, to produce hierarchical crystal structures. Infrared radiation can directly excite the functional groups involved in these intermolecular interactions, thereby inhibiting the formation of specific bonds and the nucleation of specific crystals.

This paper discusses the design and operating principles of a novel crystal precipitation system that incorporates the above-mentioned selective-wavelength infrared irradiation technique. We also present experimental results demonstrating crystal polymorph control for Ritonavir, an active pharmaceutical ingredient, as a potential real-world application.

2. Experimental Apparatus

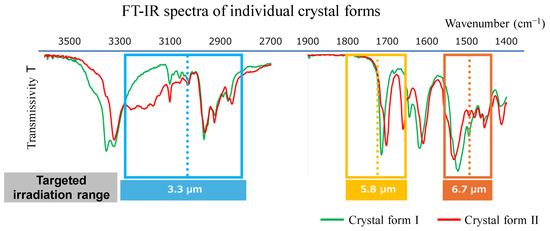

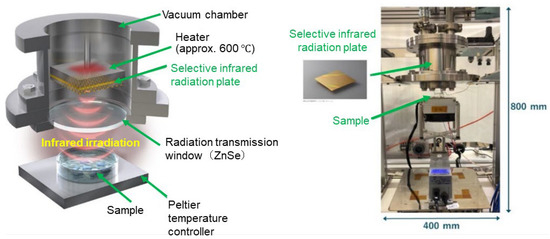

This crystallization method is based on what is known as the evaporation method, the most distinctive feature of which involves the continuous irradiation with infrared radiation at selected wavelengths during the solvent evaporation process—i.e., during solute recrystallization. The solute crystals are obtained as residues after the solvent is completely removed by drying. Infrared radiation is the electromagnetic radiation emitted by the random thermal vibrations of a molecule. Thus, it typically exhibits very weak wavelength selectivity and directionality in radiation, which is the propagation phenomenon of the emitted electromagnetic waves. In practice, as will be described later, infrared wavelength control requires significant engineering work. While reports do exist on basic research and the processes that account for the spectral affinity between emitters and absorbers [18,19,20,21], very few case studies have been performed to date.

To achieve infrared wavelength selection for the purposes of this study, we developed a selective-wavelength MIM emitter. The main wavelength of the radiation from this MIM emitter can be set arbitrarily within the range of approximately 3.0 μm to 8.0 μm, depending on the structural design. While the half-widths of the main wavelength band vary slightly depending on the wavelength, the bandwidth is typically narrow, at around 0.4 μm, and rarely exceeds 1.0 μm. This enables the emitter to target absorption bands of specific functional groups found in various organic compounds. This feature is expected to have the effect of dissociating the aggregates produced by specific intermolecular interactions through selective excitation of the vibration of the target functional group.

It should be noted that the hydrogen bond is considered to be the strongest among the intermolecular interactions, generally on the order of several tens of kJ/mol. If we were to assume that this energy is 30 kJ/mol, it would be equivalent to approximately 0.31 eV. On the other hand, the photon energy (E) of infrared radiation with a wavelength (λ) of 3 μm can be quantized using the relationship E = hν = hc/λ [J] (where h is Planck’s constant, ν is frequency, and c is the speed of light), which gives the value 0.41 eV.

So theoretically, infrared radiation should have sufficient energy to cause dissociation of an independent hydrogen bond. Figure 1 shows the experimental apparatus equipped with this MIM emitter and the experimental system.

Figure 1.

Experimental apparatus (left: schematic illustration; and right: the actual apparatus).

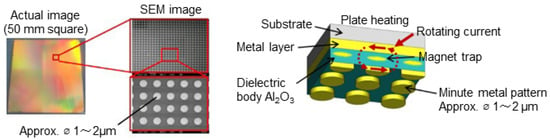

3. MIM Emitter

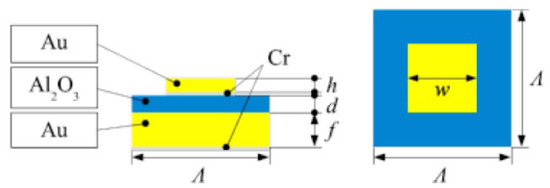

Figure 2 shows a photo of the actual MIM emitter and a schematic of its structure.

Figure 2.

The MIM emitter and its conceptual diagram (when the metal pattern is circular).

While Figure 2 shows a circular metal pattern, other shapes are possible, such as rectangular or cross shapes. For our study, we chose to use a square pattern. The principle of selective infrared irradiation by the MIM radiation plate is as follows: The three-layered structure of this metal-insulator-metal metamaterial is known to exhibit wavelength selectivity due to its magnetic resonance modes [22,23,24,25,26]. When electromagnetic waves arrive at the MIM structure, anti-parallel currents of specific wavelengths are induced in the upper and lower metal layers. These electric fields generate a magnetic field within the insulator; the changes in both fields amplify each other, enabling selective wavelength electromagnetic wave irradiation and absorption. In the method presented in this study, the MIM emitter is designed so that the main irradiation wavelength coincides with the absorption band generated by the molecular vibration of specific functional groups, which are thought to be involved in hydrogen bond formation between the solute molecules. Examples of target absorption bands include the absorption band attributable to the O-H stretching vibration of the carboxy group at around 3.0–3.3 μm and the absorption band attributable to the C=O stretching vibration of the carbonyl group at around 5.8 μm.

To fabricate the MIM structure, a metal layer is sputtered onto a sapphire substrate, followed by the deposition of aluminum oxide. The patterning on the outermost layer is then formed by electron beam lithography. An adhesive layer of Cr or similar material is added between each layer. Figure 3 and Table 1 give the detailed structure of the MIM emitters and the design values of the radiation plates used in the measurements below. The design values given in Table 1 are the specifications for the actual radiation plates used in the experiments described in Section 6.

Figure 3.

Example of the cross-sectional structure of a MIM selective radiation plate.

Table 1.

Example of the design values of the MIM selective radiation plate.

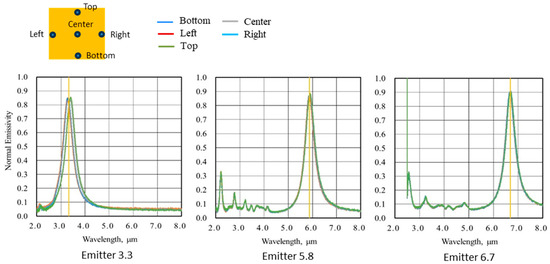

4. Radiation Energy

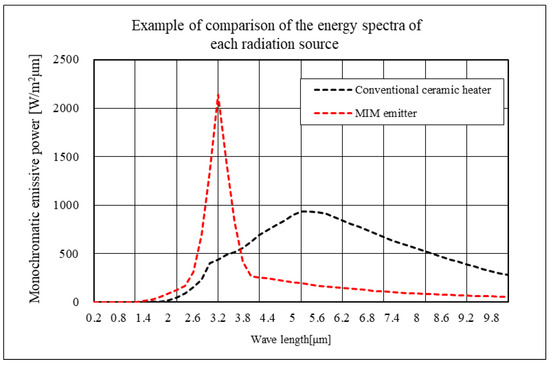

We measured the normal-incident hemispherical reflectance spectra of the emitter having the fabricated MIM structure using a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer with an integrating sphere. We then calculated the normal emissivity spectra based on assuming the sum of reflectance, absorptance, and transmissivity to be 1, Kirchhoff’s law, and the assumption that transmissivity is 0. Figure 4 shows the normal emissivity of each MIM emitter presented in Table 1. The yellow vertical line in each plot indicates the target wavelengths for each emitter. We measured normal emissivity at five points: center, top, bottom, left, and right. Although the spectral shapes of the five points show a slight deviation at 3.3 μm, they are very similar, and the graphs are displayed almost overlapping. Despite small peaks attributable to higher-order resonance modes on the shorter wavelength side, we confirmed that high emissivity is achieved mainly around the target wavelength. For example, in the case of Emitter 3.3, a peak of normal emissivity occurs at around 3.3 μm with a half width of approximately 0.4 μm. The MIM emitter records normal emissivity exceeding 0.84 at all target wavelengths, achieving high values. Figure 5 compares the spectral radiant energy of the MIM emitter and a conventional ceramic heater at equivalent input energies. We see that the MIM emitter exhibits significantly improved narrow-band radiation spectrum characteristics compared to the conventional ceramic heater. Since the radiation energy is strongly dependent on the temperature of the MIM emitter itself, the emitter is typically heated to approximately 600 °C using a separate heat source in the experiments to achieve the desired effect. The infrared energy on the liquid surface is approximately 0.2 to 0.3 [W/cm2].

Figure 4.

Normal emission spectra of the MIM emitters.

Figure 5.

Comparison of emission spectra.

5. Experimental Method

We performed an IR-induced crystallization experiment for crystal polymorphs using the experimental apparatus described in Section 2 and Section 3. The apparatus shown in Figure 1 is housed in a PET resin case that can isolate it from the external air. Dry air (at a dew point of approx. −5 °C) is fed into the case at approximately 15 L/min. A Petri dish containing the sample is placed on the Peltier temperature controller, directly below the ZnSe plate serving as the radiation transmission window. The sample consists of a solution in which the target substance to be crystallized (solute) is completely dissolved (confirmed visually) in the specified solvent. While the amount of solvent and solute can be set arbitrarily, 20 to 200 mg of a solute is typically dissolved in about 1 mL of solvent (See Supplement S4 for details).

The surface of the MIM emitter is heated using a ceramic heater attached to the back side and maintained at approximately 400 to 600 °C throughout the experiment. However, since the MIM emitter is housed in a vacuum chamber in which convective heat transfer is blocked, the temperatures around the sample can be freely adjusted, regardless of heater temperature. The top part of the Petri dish is in contact with the air inside the case. Heat exchange occurs between the solution and the air through natural convective heat transfer. The solvent evaporated from the liquid surface is transported and diffused inside the container by natural convection and removed from the system through the exhaust port attached to the case. Thus, the solution temperature is determined by a complex physiochemical process that involves a combination of multiple factors, including the selective wavelength radiation from the ZnSe window, convective heat transfer within the case, the latent heat of evaporation of the solvent, the heat of dissolution and solidification of the solute, and heat transfer at the contact between the Petri dish and the Peltier temperature controller, all of which continuously change with time. After the completion of solvent crystallization (absolute dryness), the crystals in the Petri dish are collected and their crystal forms verified by powder XRD and other analytical methods.

7. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed a novel crystallization method that incorporates infrared irradiation using a metamaterial-type emitter (MIM emitter) capable of emitting infrared radiation at selected wavelengths. We demonstrate its potential application to the screening of crystal polymorphs of active pharmaceutical ingredients. Our crystallization method, based on the evaporation method, which involves infrared irradiation at a specific wavelength during the recrystallization process, can contribute to the ultimate control of crystal polymorphs by directly influencing crystal nucleation due to intermolecular interactions.

In particular, since MIM emitters are capable of narrow-band and wavelength-selective infrared irradiation, wavelengths that coincide with the vibrational absorption bands of functional groups can be selected to achieve selective excitation at the molecular level. In an experiment with the protease inhibitor Ritonavir, we were able to induce the selective formation of a pseudo-stable phase (crystal form I) or the most stable phase (crystal form II) by selecting the irradiation wavelength, suggesting that selective infrared wavelength absorption by intermolecular hydrogen bond networks may play an essential role in the control of crystal polymorphs.

This study introduces infrared irradiation as a new control factor in addition to solvent, temperature, precipitation rate, and other such conventional factors for crystallization. We anticipate our method to become a promising technique for strategically controlling crystal polymorphs in pharmaceutical manufacturing. In future studies, we plan to further analyze the mechanism by which infrared irradiation influences the crystal nucleation process using spectroscopic methods and simulations, with the goal of developing a new and universally applicable crystallization control method.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cryst15080741/s1, Supplement S1. Detailed experimental conditions; Supplement S2. XRD data of samples obtained under each condition; Supplement S3. Differences in hydrogen-bonding patterns between the two crystal forms of Ritonavir; Supplement S4. Detailed experimental methodology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K.; Methodology, T.T., S.O., D.K. and N.T.; validation, Y.K., D.K. and N.T.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.K.; writing—review and editing, T.T., S.O., D.K. and N.T.; Supervision, N.T.; Project administration, Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Y.K. and D.K. are employees of NGK INSULATORS, Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Ainurofiq, A.; Dinda, K.; Pangestika, M.W.; Himawati, U.; Wardhani, W.D.; Sipahutar, Y.T. The effect of polymorphism on active pharmaceutical ingredients: A review. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 11, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Gao, Z.; Gao, Z.; Huang, W.; Wan, X.; Rohani, S.; Gong, J. Controlled crystallization of metastable polymorphic pharmaceutical: Comparative study of batchwise and continuous tubular crystallizers. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 266, 118277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, K.; Ueda, K.; Moribe, K. Recent progress of structural study of polymorphic pharmaceutical drugs. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 117, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiński, P. Polymorphism of active pharmaceutical ingredients. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2006, 29, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Rohani, S. Polymorphism and crystallization of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 884–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lv, C.; Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, X. An overview on polymorph preparation methods of active pharmaceutical ingredients. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 24, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugden, I.; Braun, D.; Bowskill, D.; Adjiman, C.; Pantelides, C. Efficient screening of coformers for active pharmaceutical ingredient cocrystallization. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 4513–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañellas, F.M.; Verma, V.; Kujawski, J.; Geertman, R.; Tajber, L.; Padrela, L. Controlling the polymorphism of indomethacin with poloxamer 407 in a gas antisolvent crystallization process. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 43945–43957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C. Recent Advances in Drug Polymorphs: Aspects of Pharmaceutical Properties and Selective Crystallization. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 611, 121320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, H.; Nielsen, C.; Schroeder, B.; McCulloch, I. The role of chemical design in the performance of organic semiconductors. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2020, 4, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Shao, M.; Xiao, K.; He, Z.; Li, D.; Lokitz, B.; Hensley, D.; Kilbey, S.; Anthony, J.; Keum, J.; et al. Conjugated polymer-mediated polymorphism of a high performance, small-molecule organic semiconductor with tuned intermolecular interactions, enhanced long-range order, and charge transport. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 4378–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.J.; Diao, Y. Polymorphism as an emerging design strategy for high performance organic electronics. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 3915–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Y.; Lenn, K.; Lee, W.-Y.; Blood-Forsythe, M.; Xu, J.; Mao, Y.; Kim, Y.; Reinspach, J.; Park, S.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; et al. Understanding polymorphism in organic semiconductor thin films through nanoconfinement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17046–17057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Balawi, A.; Leenaers, P.; Ning, L.; Heintges, G.; Marszalek, T.; Pisula, W.; Wienk, M.; Meskers, S.; Yi, Y.; et al. Impact of polymorphism on the optoelectronic properties of a low-bandgap semiconducting polymer. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Tao, X. Recent Advances in Polymorph Discovery Methods of Organic Crystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reutzel-Edens, S.M. Achieving polymorph selectivity in the crystallization of pharmaceutical solids: Basic considerations and recent advances. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 2006, 9, 806–815. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, K.; Hodnett, V.V. Thermodynamic vs. kinetic basis for polymorph selection. Processes 2019, 7, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y. Wavelength Control Infrared Heating System. In Proceedings of the 20th International Drying Symposium (IDS2016), Gifu, Japan, 7–10 August 2016; p. P0392. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnan, T.; Kondo, Y.; Aoki, M.; Inasawa, S. How do drying methods affect quality of films? Drying of polymer solutions under hot-air flow or infrared heating with comparable evaporation rates. Dry. Technol. 2022, 40, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totani, T.; Sakurai, A.; Dao, T.D.; Nagao, T.; Kondo, Y. Application of the Wavelength Selective Emitter with the Metamaterial of a Meta-Insulator-Metal to an Infrared Ray Drying Furnace. In Proceedings of the 16th International Heat Transfer Conference (IHTC-16), Beijing, China, 10–15 August 2018; Volume IHTC16-24220, pp. 5901–5908. [Google Scholar]

- Tanada, Y.; Totani, T.; Odashima, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Kondo, Y. Relaxation Enhancement from Intra- to Intermolecular Vibrations in Water Continuously Excited by Wavelength-selective Infrared Radiation. In Proceedings of the 3rd Pacific Rim Thermal Engineering Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 15–19 December 2024; Volume PRTEC-24076. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.J.; Wang, L.P.; Zhang, Z.M. Coherent thermal emission by excitation of magnetic polaritons between periodic strips and a metallic film. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 11328–11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puscasu, I.; Schaich, W.L. Narrow-band, tunable infrared emission from arrays of microstrip patches. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 233102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, S.; Kimata, M. Metal-insulator-metal-based plasmonic metamaterial absorbers at visible and infrared wavelengths: A review. Materials 2018, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T.; Dao, T.D.; Chen, K.; Ishii, S.; Sugavaneshwar, R.P.; Kitajima, M.; Nagao, T. Spectrally selective mid-infrared thermal emission from molybdenum plasmonic metamaterial operated up to 1000 °C. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2016, 4, 1987–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, A.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, Z.M. Prediction of the Resonance Condition of Metamaterial Emitters and Absorbers using LC Circuit Model. In Proceedings of the 15th International of Heat Transfer Conference (IHTC-15), Kyoto, Japan, 10–15 August 2014; Volume IHTC15-9012, pp. 7067–7076. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, J.; Spanton, S.; Henry, R.; Quick, J.; Dziki, W.; Porter, W. Ritonavir: An Extraordinary Example of Conformational Polymorphism. Pharm. Res. 2001, 18, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morissette, S.L.; Soukasene, S.; Levinson, D.; Almarsson, Ö. Elucidation of crystal form diversity of the HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir by high-throughput crystallization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2180–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).