1. Introduction

The presence of surface acoustic waves (SAW), also known as Rayleigh waves, in mechanically isotropic half-space media is derived from the inhomogeneous or evanescent solutions of the Christoffel equation together with the free surface boundary condition [

1]. Their displacement vector lies in the sagittal plane, and they decay exponentially with increasing distance from the surface into the medium. The nonradiative nature of the Rayleigh wave sets a limit on its velocity, which is always lower than the velocity of any bulk wave in the material. The isotropic half-space system also supports a radiative or leaky wave with a velocity between the transverse and longitudinal bulk wave velocities for a certain range of the Poisson’s ratio (

) [

2]; while radiating away from the surface into the bulk, the leaky wave is attenuated as it propagates along the surface, and its velocity is thus a complex-valued quantity. Rayleigh and leaky waves are nondispersive in the long wavelength limit. In addition, polarized surface acoustic waves perpendicular to the sagittal plane do not exist on these surfaces.

SAWs exist in any direction on the surface of anisotropic materials, with some differences compared to the isotropic case, such as in the variation of the velocity with the propagation direction and in the form that the amplitude of the wave decays with depth beneath the surface [

3,

4]. The dependence of the modes on the propagation direction in anisotropic media gives rise to the emergence of leaky surface waves that have no parallel in isotropic media. For example, anisotropy of the (001) surface of cubic crystals leads to the removal of the two-fold bulk transverse-mode degeneracy and the mixing of longitudinal and transverse polarizations. The coupling between the Rayleigh wave and the slowest quasi-transverse bulk wave when the propagation direction changes from the [100] to the [110] direction generates an anticrossing of the two branches [

5,

6]. The leaky upper branch exhibits the presence of modes for which the leakage to the bulk is suppressed, and they have been identified as the class of states known as bound states in the continuum (BIC). This occurs in a specific direction between the crystallographic [100] and [110] directions and in the exact [110] direction [

7,

8]. These are examples of parametric or

accidental BIC, which is generated in this case by the coupling of modes, and symmetry-protected BIC, respectively, [

9].

Leaky waves in anisotropic solids have been extensively studied and have become technologically relevant, as in some cases, their high phase velocity together with an optimal electromechanical coupling compensates for the propagating losses. Although not always identified as BICs, the low-propagation-loss modes found in certain orientations of LiNb0

3, quartz, and LiTa0

3 have been used for the development of radio-frequency devices [

10,

11,

12]. More recently, high-frequency low-loss devices were realized using unattenuated SAWs present in leaky mode branches with a strong longitudinal character in layered structures combining thin films and anisotropic substrates [

13,

14,

15].

The presence of an intrinsic characteristic length in half-infinite media, such as the thickness of an added layer [

16] or the periodicity of a grating [

17], leads to the appearance of spatial dispersion when the inhomogeneity of the properties in the media is introduced. In such a case, the nontrivial dispersion relations favor the transition of surface modes to leaky modes, enabling the presence of waves with a velocity larger than the limiting transverse bulk counterpart.

Accidental BICs can exist in the branches of these leaky modes if the appropriate conditions are met. This applies to all isotropic layers in half-infinite media studied in systems comprising flat surfaces [

18], surface gratings [

19,

20], and surface 2D-phononic crystal structures (SPnC) [

21]. These studies on BICs in both 1D and 2D SPnCs were conducted in layered structures, in which guided modes such as Sezawa modes may be present in addition to the Rayleigh mode. BICs were also found in the intricate band structure of 2D SPnCs formed by a square lattice of cylindrical voids in a (001) GaAs half-space [

22].

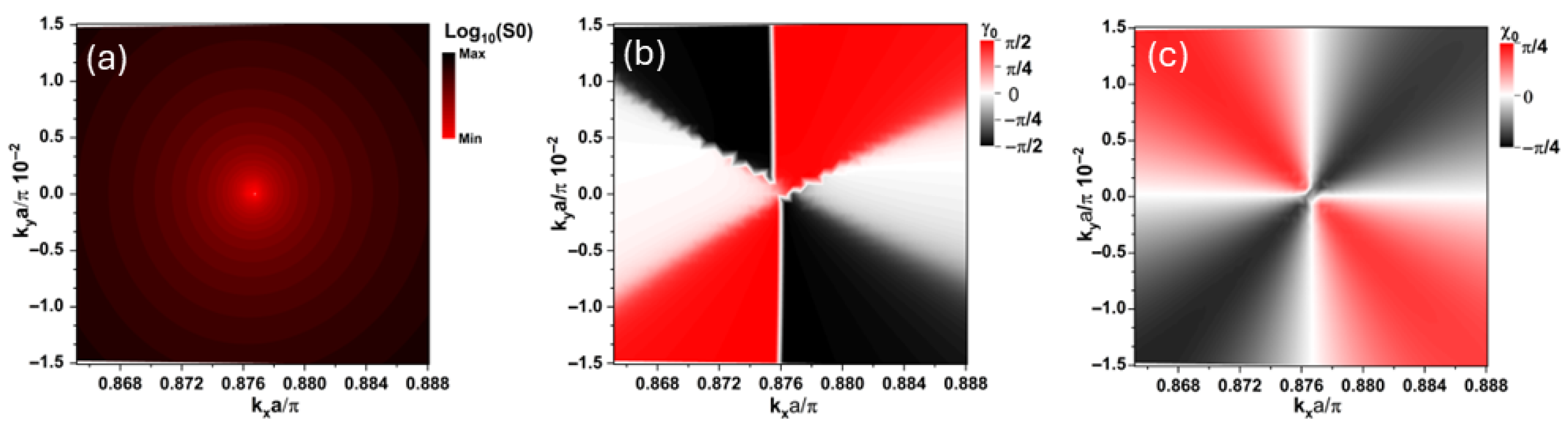

From a different perspective, BICs have been presented as polarization singularities of the radiation field in momentum space [

23,

24]. Research on the topological characteristics of BICs has largely concentrated on photonic dielectric structures, with relatively few studies focusing on acoustic waves [

21].

In this work, we present a study of SPnCs formed in mechanically isotropic half-space media using the finite element method (FEM) with a special focus on the radiative part of the frequency spectrum. The surface roughness was considered a shallow relief to prevent the presence of local resonances [

25]. Therefore, this represents the simplest case study, where isolated branches of surface and leaky modes allow the analysis of

accidental BICs that do not originate from mode coupling [

26].

2. Surface Phononic Crystal Model and Simulation Methods

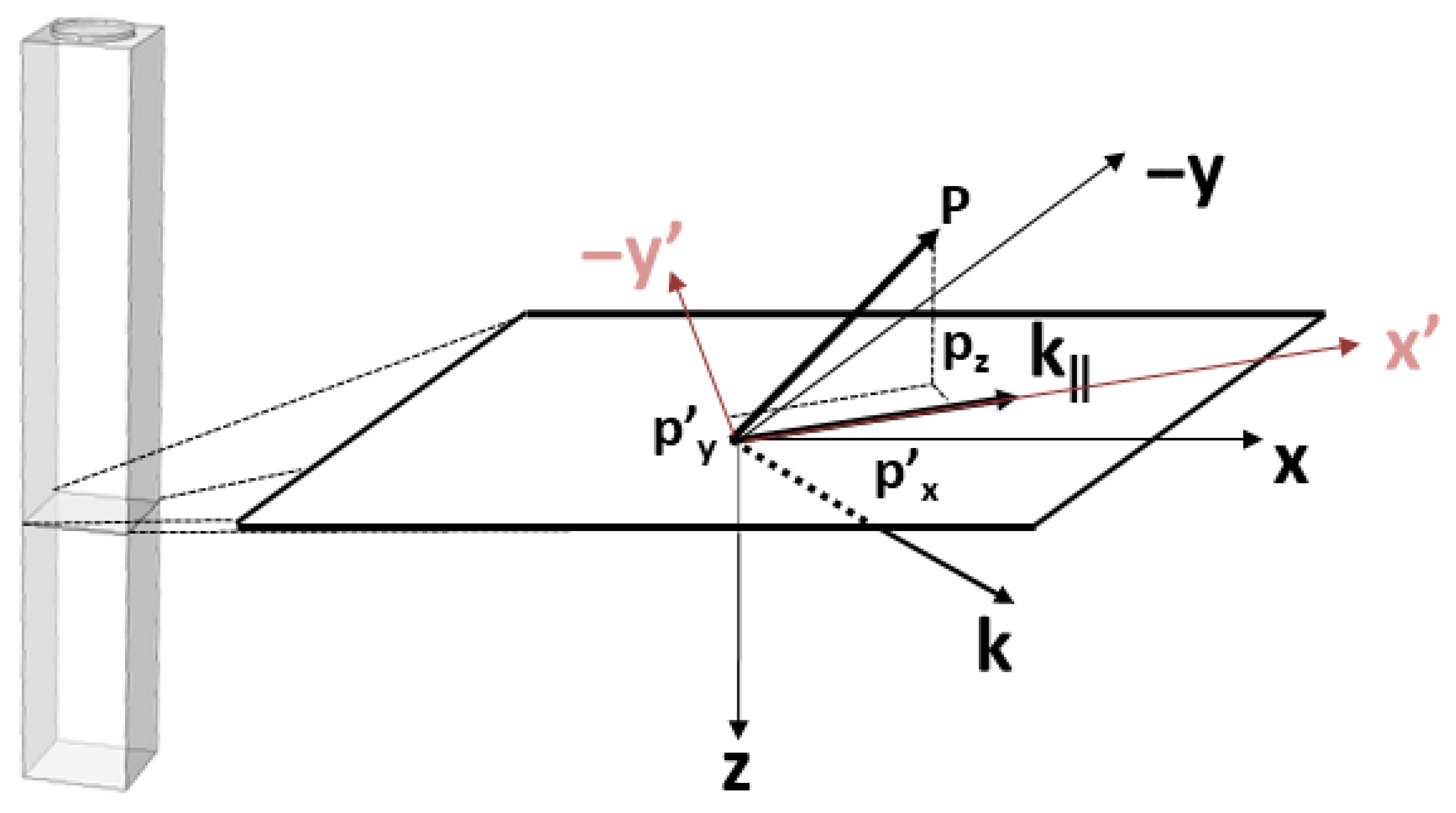

We consider a semi-infinite isotropic elastic medium, unbounded in the plane, with a surface at and extending to negative infinity. The flat surface is perturbed by a corrugated structure in the form of protruding cylinders extending periodically in the xy plane, forming a 2D surface-PnC in a square lattice ( point group). The PnC structure establishes a periodic surface profile along the plane, replacing the flat surface condition.

The FEM model using COMSOL Multiphysics 5.5 software has been shown to produce satisfactory results when simulating the band structure of surface and leaky acoustic waves in periodically patterned surfaces [

27,

28]. We seek for propagating elastic waves satisfying the governing motion equation of a linear elastic medium, which in the frequency domain reads

where

, with

, is the position-dependent component of the general solution of the displacement

, i.e., a time-harmonic plane wave with angular frequency

,

is the mass density, and

is the stress tensor. Equation (

1) is complemented by the boundary conditions derived from the presence of a free surface and the periodicity of the PnC lattice. The first requires the zero stress condition on the surface, thus

where

is a unit vector normal to the surface at each point. The second introduces the Bloch-Floquet periodic boundary conditions on a single cell of the square SPnC [cf.

Figure 1a] so that each

has associated a wave vector

such that

for every

in the lattice.

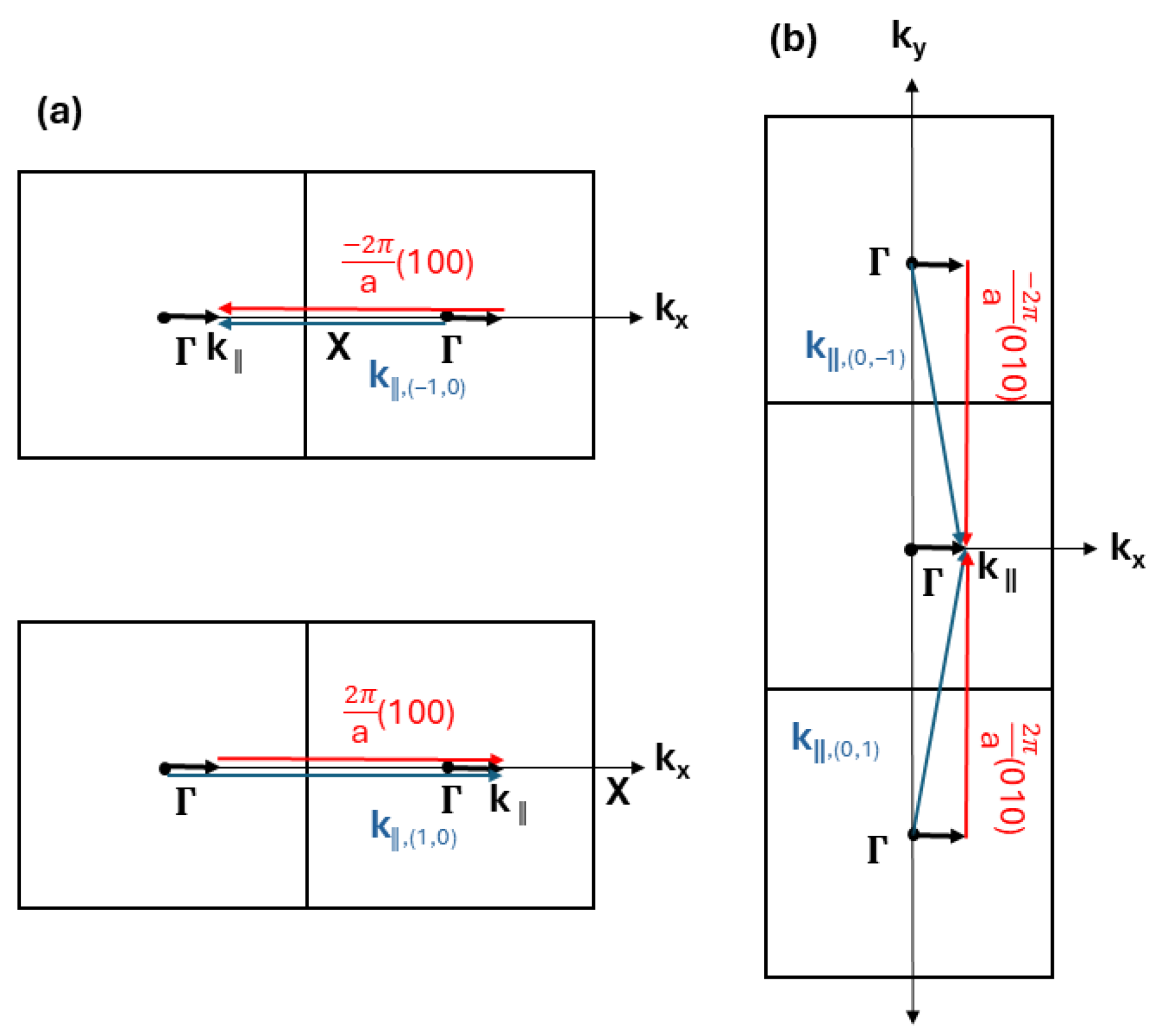

The general reciprocal lattice vector

of the 2D-square lattice characterized by a period

a is given by

where

n,

m are integers and

,

are primitive reciprocal vectors. The reciprocal lattice vectors and first Brillouin zone are shown in

Figure 1b.

As a consequence of Equation (

3),

is the product of

and a periodic function

. By expanding the periodic function

in a Fourier series, a wave propagating with an in-plane 2D wave vector

can be represented as an infinite number of traveling wave components. The wave vectors of these wave components or space harmonic are expressed as

Even if periodic boundary conditions place a constraint on the lateral dimensions of the problem, it is necessary to address the truncation of the unit cell in the z direction when working with FEM. When searching for SAWs sustained by the SPnC, it is necessary to ensure that the length of the bounded domain in the z direction is greater than the penetration depth of the SAWs. Therefore, the depth of the structure must encompass several wavelengths to obtain a reliable solution that accurately describes the vanishing acoustic field in the direction perpendicular to the surface. An unintended consequence of domain truncation is the emergence of multiple solutions from the resulting plate-like structure. Different sorting methods based on the mechanical energy distribution inside the structure have been used to distinguish the surface modes from the modes that satisfy the top and bottom surface boundary conditions simultaneously.

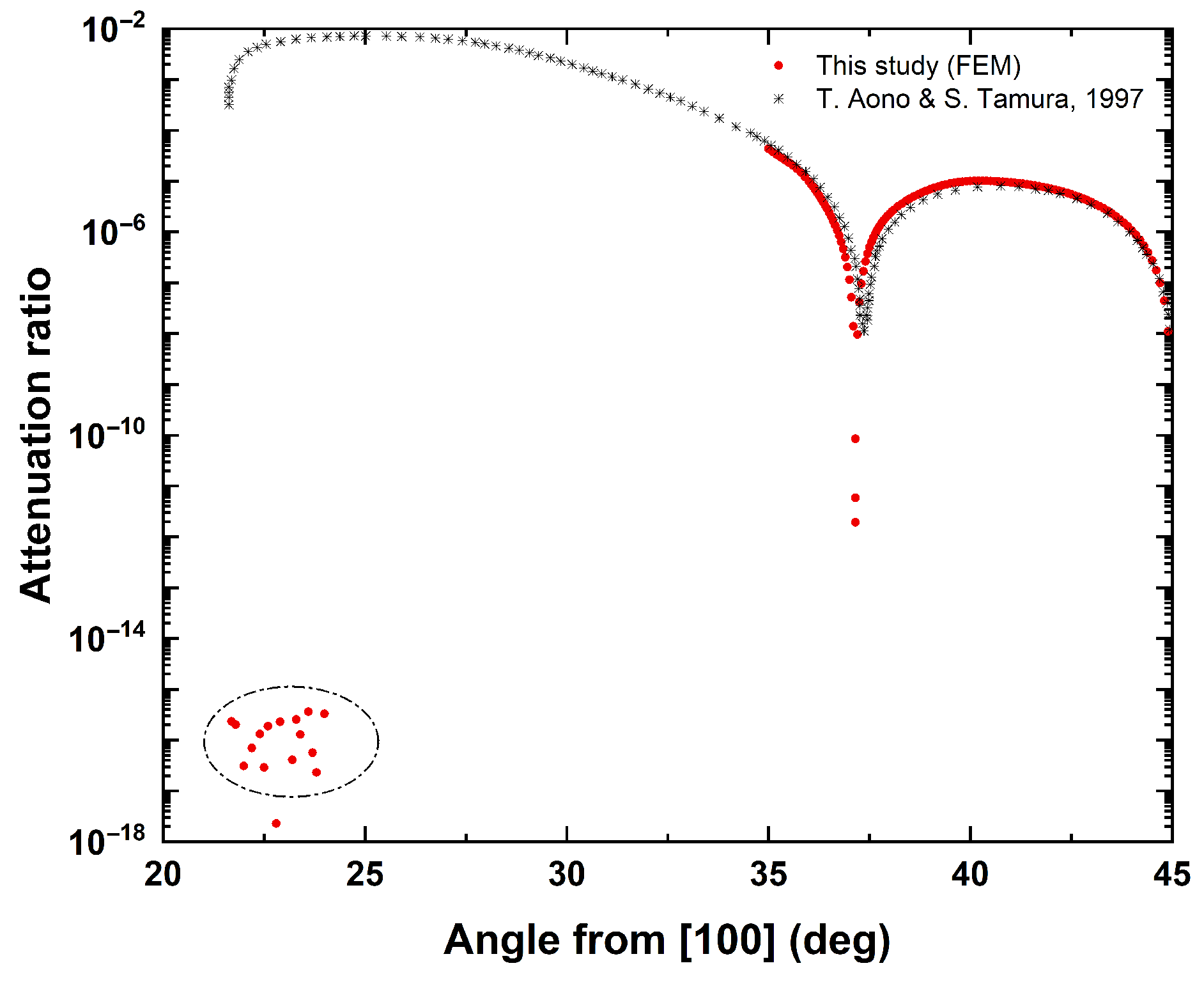

Nevertheless, the search for solutions describing radiative waves relies on avoiding reflections from the bottom of the computational domain owing to leakage. Perfectly matched layers (PML) and viscoelastic absorbing regions (VAR), which were previously used to avoid undesired reflections from bounded domains in the material’s response to a mechanical excitation [

29,

30], have also been applied in the simulation of frequency spectra within the radiative region accessing radiative waves with accurate displacement profiles [

22,

31]. Moreover, adding an absorbing region results in complex-valued eigenfrequencies,

, for the modes that propagate in this region, with a large imaginary part in the case of plate-like modes compared to radiative modes. Therefore, the magnitude of

can be used to sort the FEM solutions by distinguishing between the true nonradiative and radiative waves and discarding unwanted plate-like modes. In addition, the attenuation ratio,

written as

, quantitatively accounts for the radiation of power into the semi-infinite solid (see

Appendix A).

COMSOL FEM eigenfrequency analysis was conducted for the single cell shown in

Figure 1a with period

a and forming a cylindrical pillar of diameter

d and height

h on the surface. It is built by a 95

a deep, three-dimensional domain formed by a linear elastic and isotropic material. In this case, Equation (

1) is

where we have introduced the relation between the speeds of sound for bulk longitudinal,

, and transverse,

sound waves and the components of the elastic constant tensor

c, which relates stress and strain, i.e.,

. We have chosen an archetypical material with a Poisson ratio of

(

) (in the range of Al alloys and Sn) and, for convenience, we have taken

m/s. To model the half-space condition of the simulated structure, an additional absorbing layer with a height of 15

a was constructed by introducing imaginary parts to the material properties, as done in the improved version of the VAR model by Wei Ke [

32].

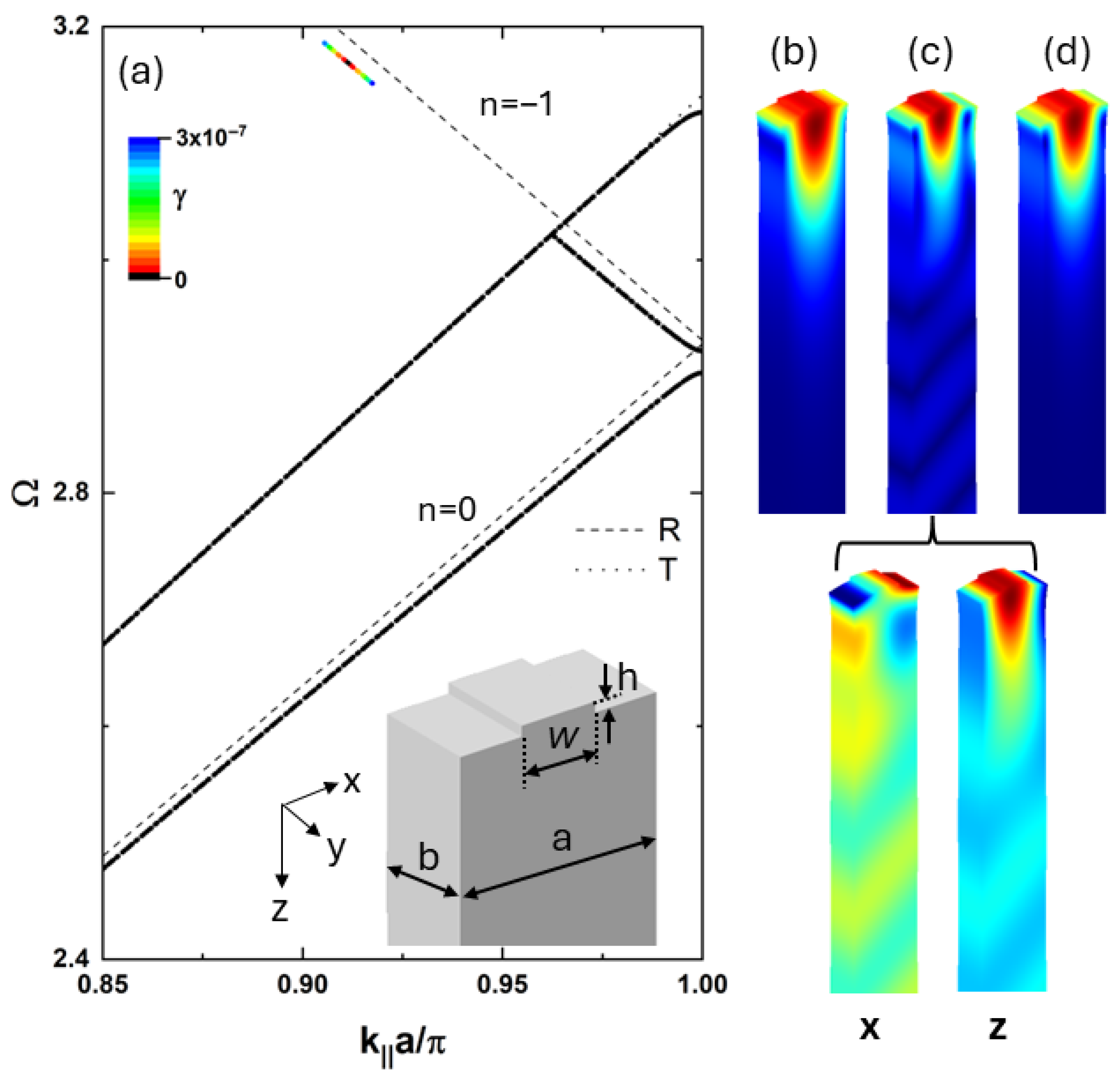

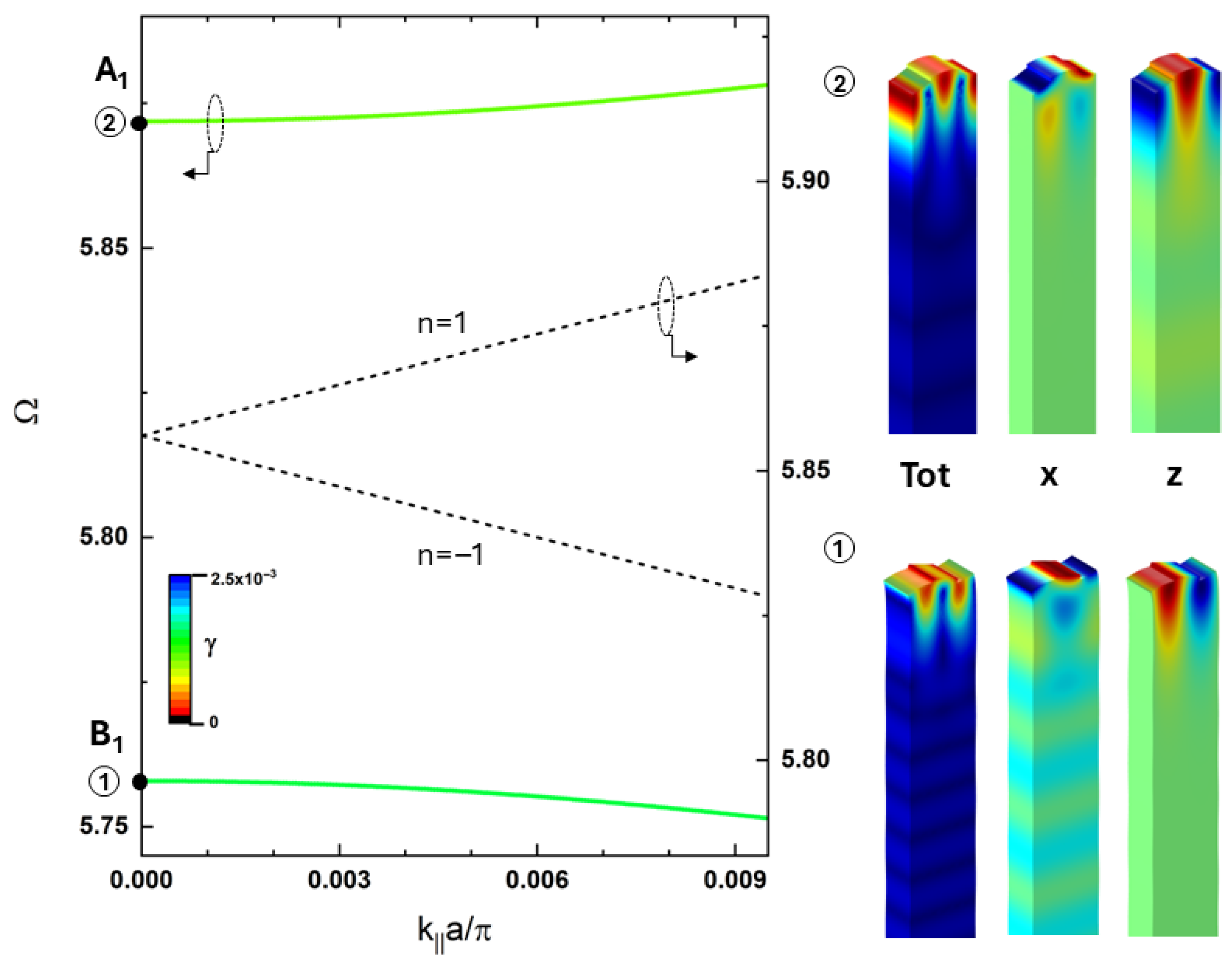

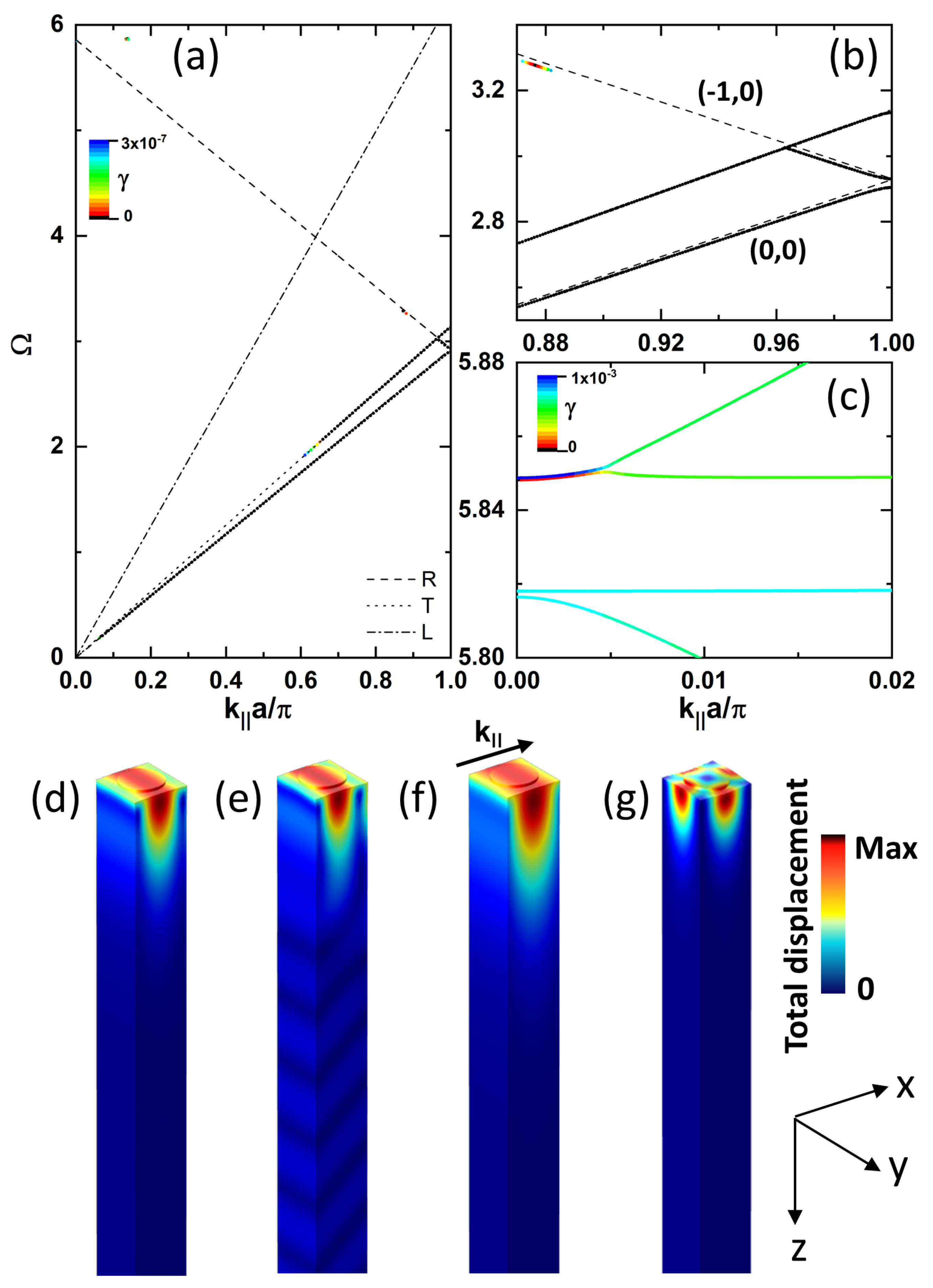

4. Discussion

In a good approximation, band structure in the

axis of the 1st Brillouin zone of the square-lattice 2D SPnC is very similar to that of modes propagating in the direction normal to the stripes of a 1D grating or 1D SPnC (simulated band structure is discussed in

Appendix D). This is appropriate for Rayleigh-like modes below and above the 1st frequency gap and for modes in the radiative region. In this section, we demonstrate that the similarity in the band structures of the two crystal configurations, including the presence of an

accidental BIC mode in both instances [see

Figure 2b and

Figure A8a], is attributed to the contribution of equivalent space harmonics in the two crystal structures to the modes propagating along

. Here, the partial-wave method applied to the 1D case [

17] is used to achieve a conceptual understanding of how elastic waves propagate in a 1D grating, which can be extrapolated to the 2D case. In contrast, the region close to the 2nd frequency gap at

requires a separate discussion, which is presented in

Appendix B.

Seeking for solutions for the solid in the form of plane waves,

the motion Equation (Equation (

6)) leads to

The solutions to the characteristic equation of Equation (

12), assuming an isotropic material, and propagation in the

plane (

), are

By substituting Equation (

13) into Equation (

12), the polarization vectors

for the six waves are determined:

These solutions correspond to two longitudinal waves of velocity

and two transverse (shear vertical) waves of velocity

polarized in the

plane, and two transverse (shear horizontal) waves of velocity

polarized in the

y direction. Each pair is composed of upward and downward propagating waves with the same

but opposite signs:

In addition to solutions with real-valued , solutions with imaginary-valued , corresponding to inhomogeneous evanescent waves, are also permitted.

The displacement vector of the waves propagating in a grating formed by a periodic surface configuration

oriented along the

x direction and characterized by a period of

a is described by a weighted superposition of the three solutions traveling downward from the surface as

that satisfies the stress-free boundary condition. The partial waves in Equation (

16) are expressed as an infinite series of traveling wave components. The wave vectors of these wave Fourier components or space harmonics are

where

denotes the primitive reciprocal lattice vector. This corresponds to the one-dimensional (1D) counterpart of Equation (

5) [

37]. Equation (

13) are modified accordingly as

with

for

and

for

. Although the general displacement of the waves propagating in the grating is represented as a linear combination of the three waves propagating into the bulk, when studying the propagation direction normal to the grooves, waves polarized in the sagittal plane

are decoupled from those polarized in the direction normal to it,

Hereafter, only waves polarized in the sagittal plane are considered. Within the EL approximation, the zero-stress condition on the surface, as described by Equation (

2) with

=

, reduces to the well-known two boundary conditions for the free surface of an elastic half-space

Substituting Equation (

19) into Equation (

21) gives a pair of homogeneous linear equations for the amplitudes

and

for each space harmonic as [

38]:

with

For a nontrivial solution to exist, the determinant of the coefficients of and must vanish, and the solution to the resulting equation provides the phase velocity of the wave.

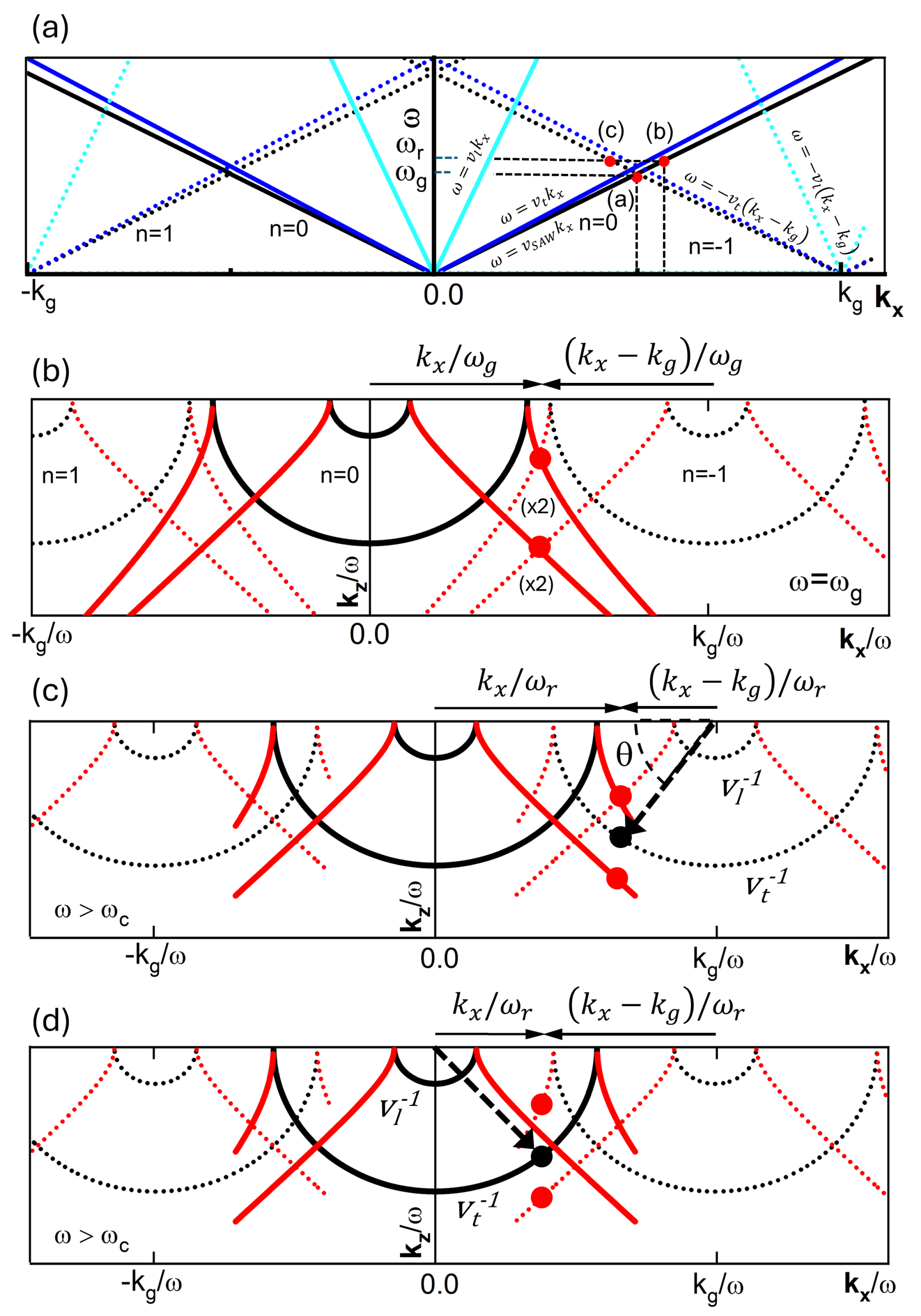

In

Figure 4a, the dispersion curve for a Rayleigh wave on a flat surface is illustrated by the solid line,

. Upon introducing the EL approximation, the dispersion diagram features an infinite number of analogous linear branches for each space harmonic

n separated by

. This configuration forms the repeated zone scheme shown in

Figure 4a, where the space harmonics

and

are partially represented. For the case where

and

, the dispersion relation derived from the EL approximation serves as an accurate representation of a weakly perturbed surface, such as the one examined in the current study. Although all space harmonics contribute to Equation (

19) and in the form of evanescent wave components (where

is imaginary), the

space harmonic predominates. For

[point (a) in

Figure 4a, the phase-matching condition between

and

harmonics,

determines the dispersion. The slowness curves of

Figure 4b illustrates the phase-matching condition that occurs for the two pairs of evanescent partial waves (imaginary-valued

) with transverse and longitudinal polarizations, respectively, from the

and

1 space harmonics. Therefore, these four terms must be considered in Equation (

19), and the dispersion relation is strongly modified from the EL approximation, giving rise to the opening of the frequency gap discussed in the main text. The partial waves of

with the propagation wave vector

and imaginary-valued solutions

that are outside the plot range in

Figure 4b do not contribute significantly to the total solution. This observation is equally applicable to all other harmonics except for

and

.

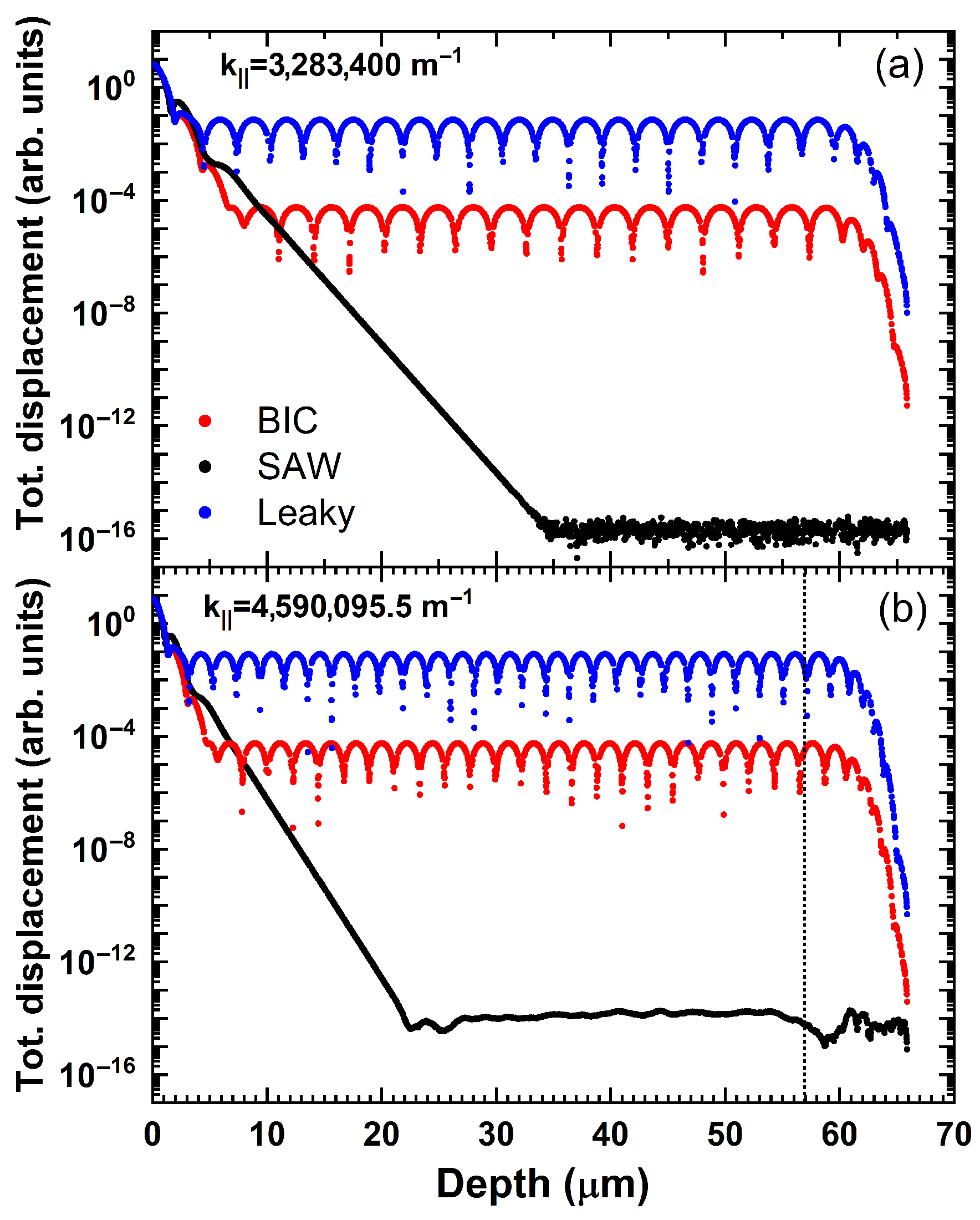

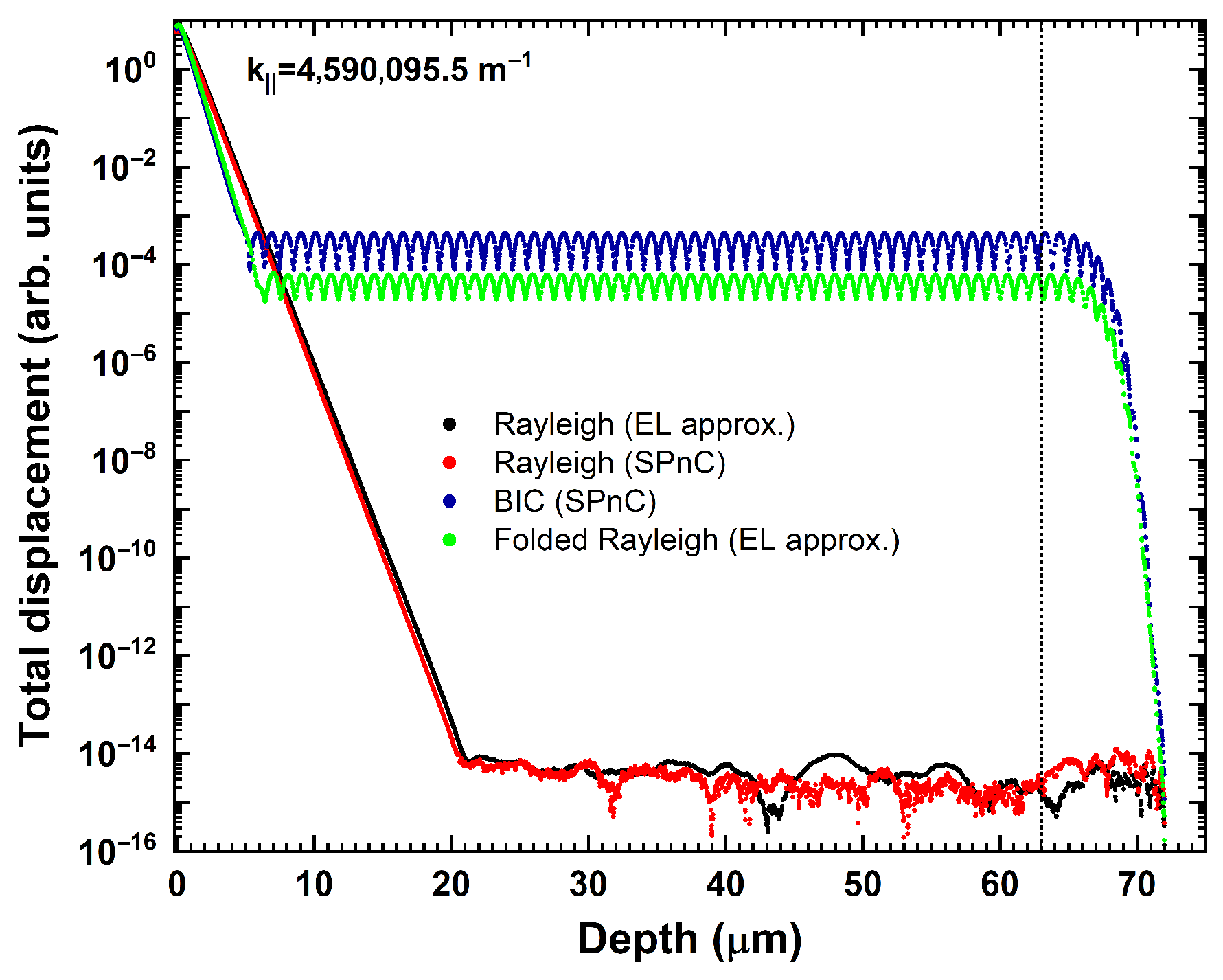

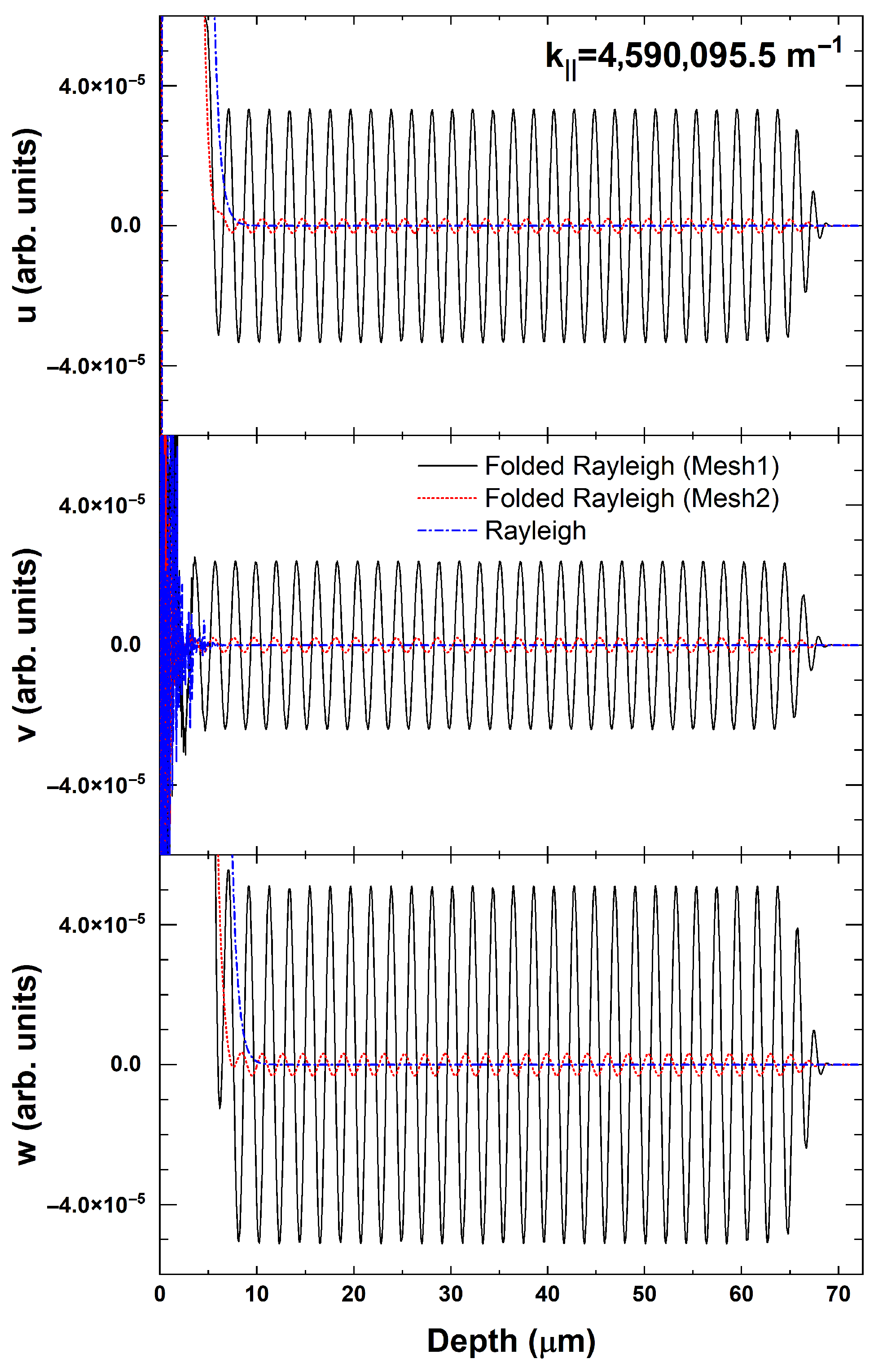

The modes of

with a frequency above the first sound line

[but below the second sound line

] of

[point (b) in

Figure 4a] are formed of partial waves of

with imaginary

values for both the longitudinal and transverse components, and partial waves of

harmonic with real-valued

transverse and imaginary-valued longitudinal components, as shown in

Figure 4c. Therefore, while the components related to

harmonic are bound to the surface, i.e., evanescent waves, the transverse component of the

harmonic radiates into the bulk. The radiative component is marked with a dashed arrow in

Figure 4c forming an angle

from the surface.

These properties established for the

space harmonic can be extended to other space harmonics owing to the periodicity. In the repeated-zone scheme illustrated in

Figure 4a, the equivalent forward-traveling modes related to space harmonics other than

characterized by a positive group velocity and all sharing the same frequency

, have wave vectors that differ by

from the wave vector of the mode of

at the same frequency. When

exceeds the critical frequency, which is defined at the intersection of the space harmonic dispersion curve

n with the first sound line of the subsequent space harmonic (

), these modes consist of a radiative wave linked to the particular space harmonic (

). Similarly, equivalent backward traveling modes with frequency

above the critical frequency, where the dispersion curve of the space harmonic

n crosses the first sound line of the preceding space harmonic (

), are composed of a radiative wave associated with this specific space harmonic (

). This is illustrated in

Figure 4d for the mode at point (c) of the dispersion curve for space harmonic

. The mode frequency is above the first sound line

of the space harmonic

. Consequently, the mode includes a radiative transverse wave component of the space harmonic

[the equivalent in 2D is

] and both longitudinal and transverse evanescent components of the space harmonic

[the equivalent in 2D is

]. The radiative component, indicated by a dashed arrow in

Figure 4d, forms an angle from the surface that is supplementary to the angle

, as given by Equation (

25) with the sign of the argument inverted or

Although this particular component does not significantly contribute to the amplitude and changes in the dispersion relation, it changes the nature of the modes by transforming them from modes bound to the surface to leaky modes, which decay as they propagate along the surface while radiating into the bulk. Consequently, the frequencies of these modes are complex valued, and the imaginary part accounts for the inverse of their lifetimes. When considering a complex frequency, the values of the solutions to Equation (

18) are also complex. In this case, the radiative partial waves possess values of

that are mainly real and have a small but non-negligible imaginary contribution. Likewise, the evanescent partial waves have

values that are essentially imaginary, but contain a small real contribution. Therefore, the point in the dispersion diagram where the modes convert from truly surface waves to leaky waves will not be given exactly by the crossing point of the dispersion relations of the surface mode and first sound line.

When an

accidental BIC arises, it results from the nullification of the radiative wave component of the leaky mode. This condition implies that the amplitude of the radiative partial wave must be zero. In the 1D and 2D PnC dispersion relations, a BIC emerges in the folded branch situated between the first and second sound lines. We previously assigned the radiative channel to the transverse component of the

harmonic based on the partial waves description and EL approximation. By setting

in Equation (

22) implies

, which provides the condition

. The position of the BIC is at the intersecting point of the condition

and the dispersion relation of the folded branch

. Then the frequency

and wavevector

of the BIC are found to be

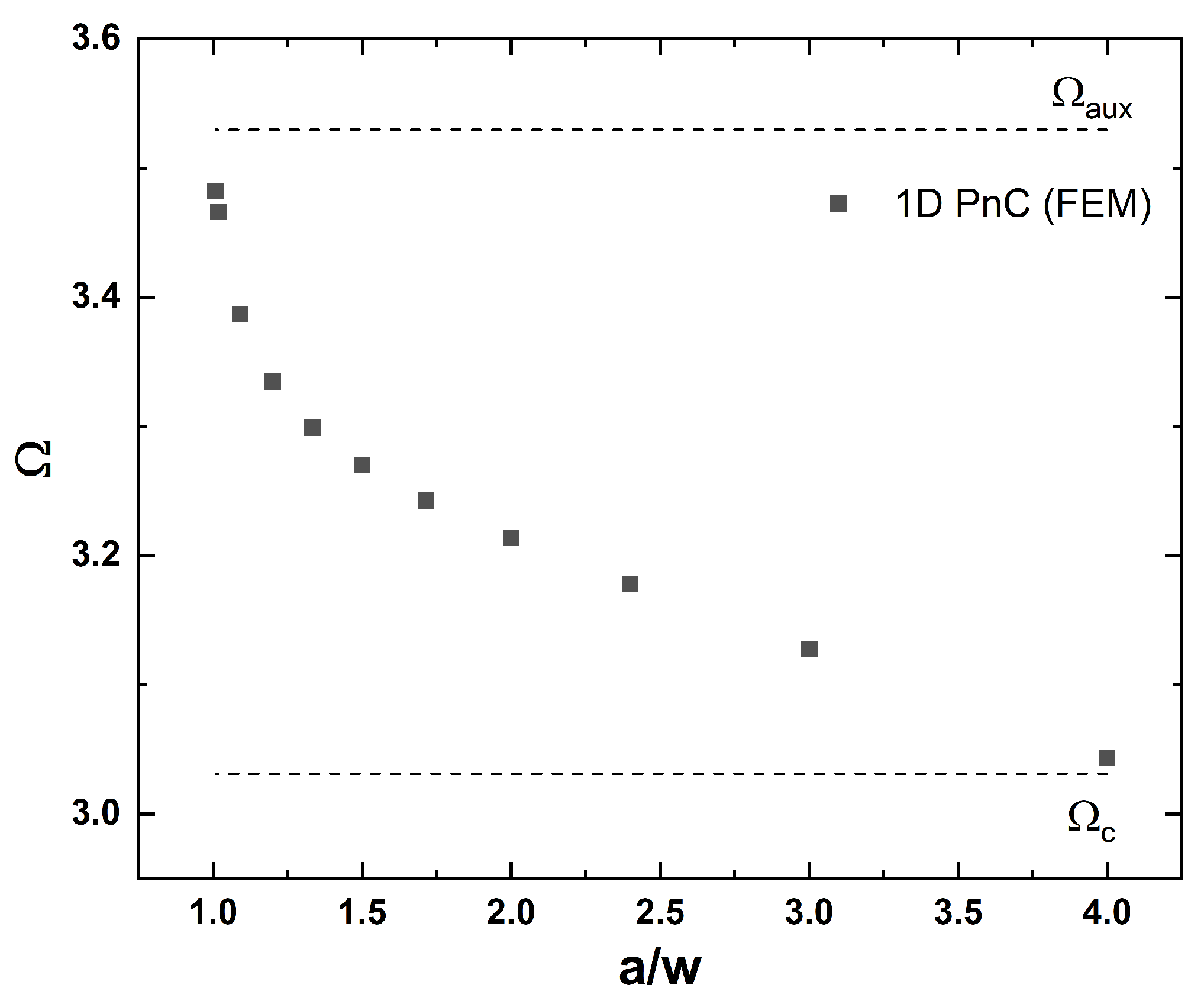

Figure 5 shows the evolution of the BIC frequency derived from the simulated band structure of a 1D SPnC by changing the groove width,

w, with a constant height of

h = 005

a. As the PnC structure approaches the flat-surface condition, the BIC frequency converges to

. The lower limit of the BIC frequency is the critical frequency

, which marks the transition from leaky to true surface mode.

In conclusion, the occurrence of the accidental BIC in SPCs with shallow surface relief does not rely on the coupling between modes or the interference from multiple radiative paths, but on the fulfillment of the condition for null amplitude of the transverse radiative channel and the dispersion relation simultaneously. An analytical value for the location of the accidental BIC on the dispersion curve was obtained using the partial-wave model and the EL approximation. Consequently, this type of BIC originates from a singular state and is associated with a single radiative channel; thus, their existence does not necessitate coupling between modes or interference from multiple radiative paths.

Furthermore,

Figure 5 illustrates the robustness of the BIC against variations in the structural parameters, specifically the groove width. The frequency of the BIC varies continuously from the existence condition, as determined by the EL approximation, to the critical value. The appearance of the

accidental BIC was also proven in a full range of Poisson’s ratios covering

. The robustness of BICs to changes in structural parameters and material properties, provided that the symmetry and periodicity of the structure are preserved, has been linked to the presence of the quantized topological index [

23].

As real systems are never perfectly periodic owing to fabrication imperfections and disorder, the practical implementation of BICs in devices such as SAW resonators may be hindered by induced radiative leakage. In addition to fabrication tolerance requirements, integrating a phononic structure with transducers on the same surface leads to complex fabrication processes involving a trade-off with enhanced device performance.