Luminescence of BaFBr and BaF2 Crystals Irradiated by Swift Krypton Ions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

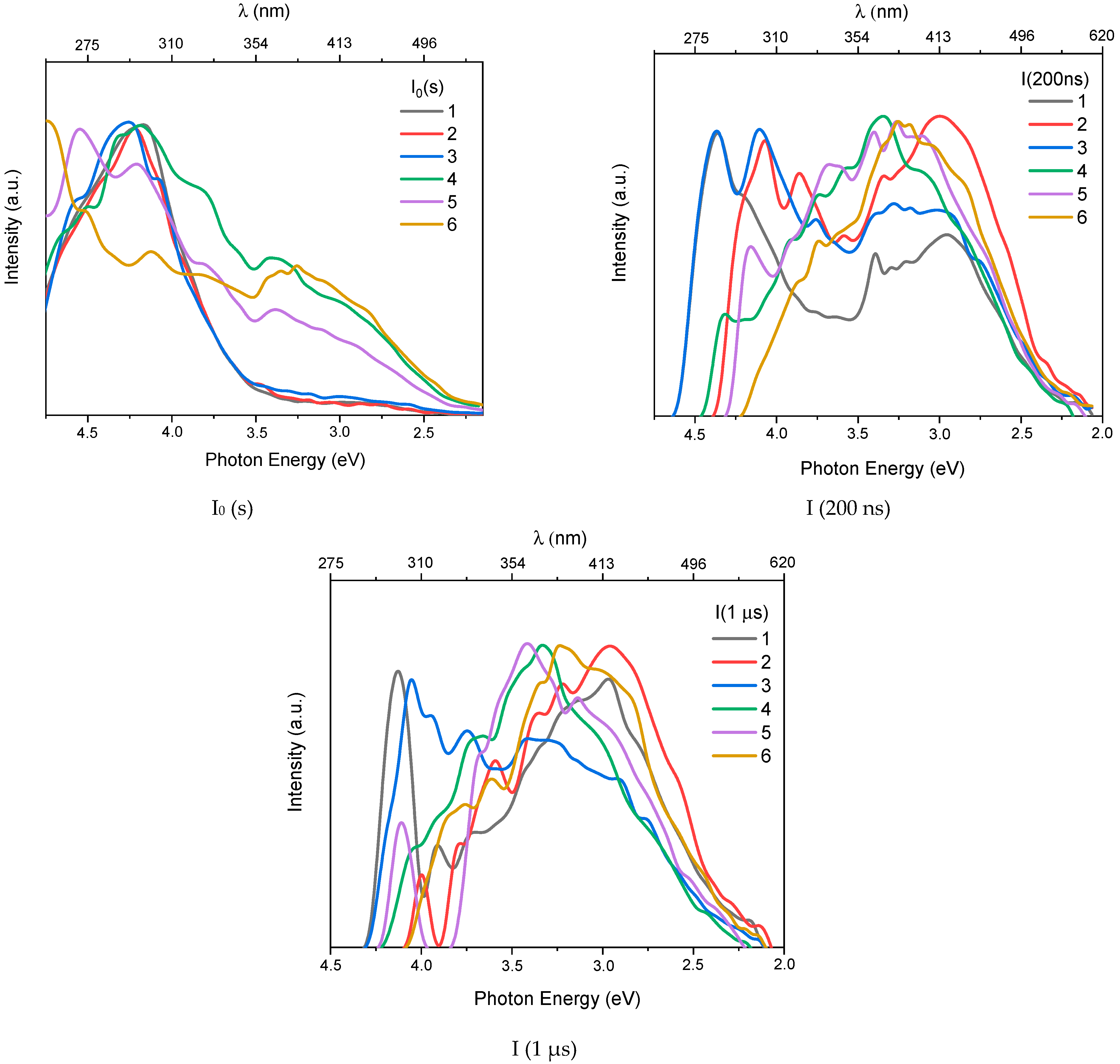

3.1. X-Ray Excited Optical Luminescence (XEOL)

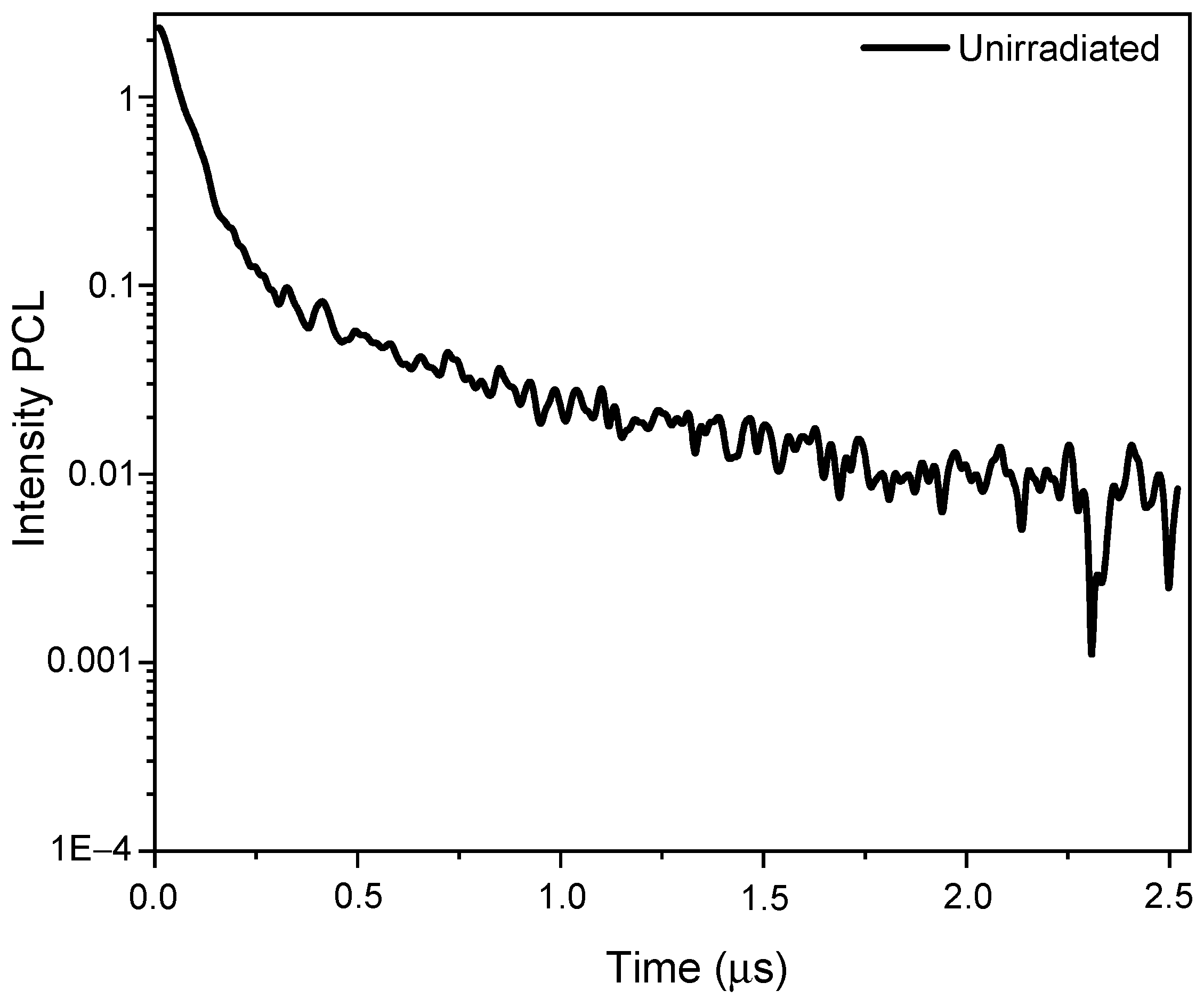

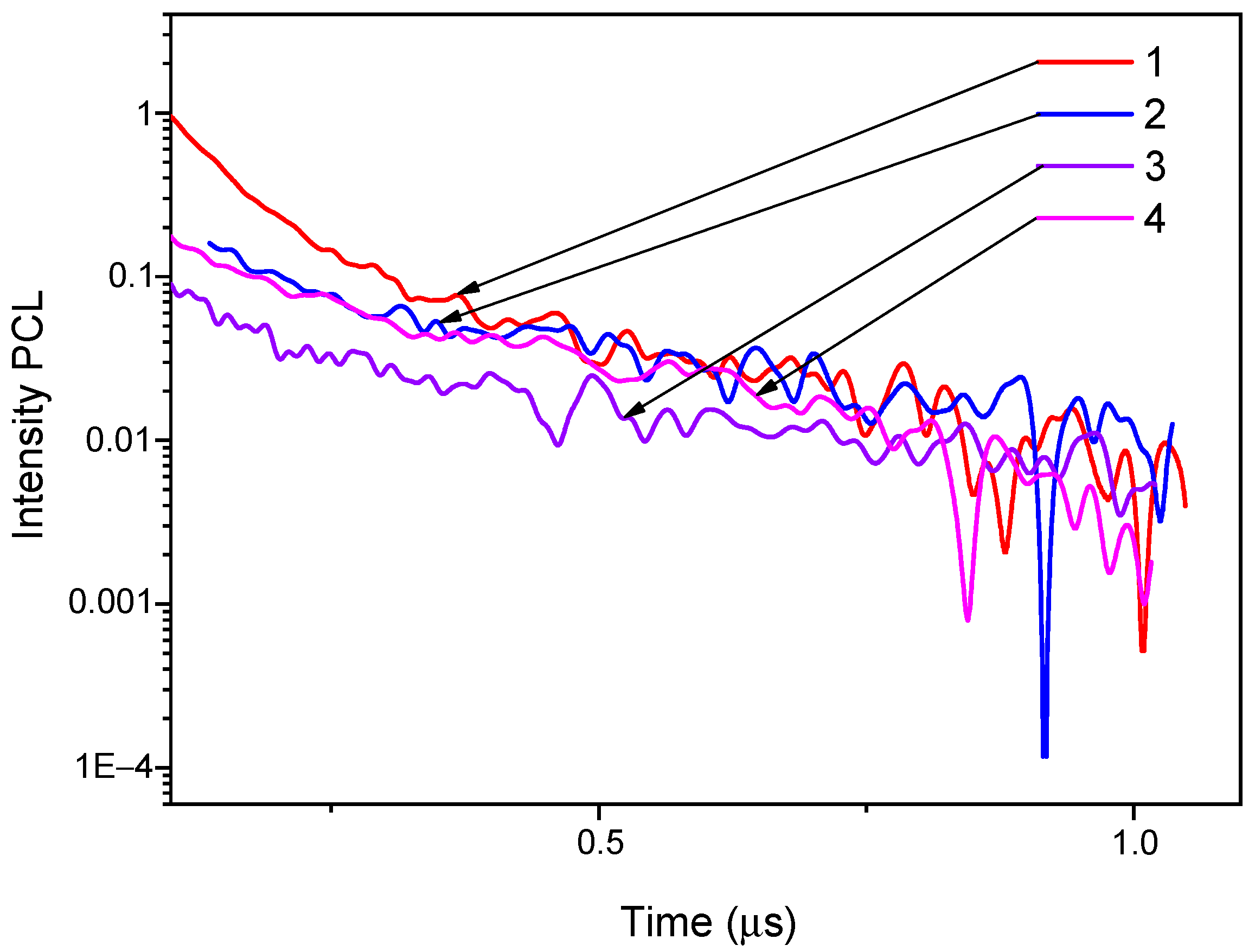

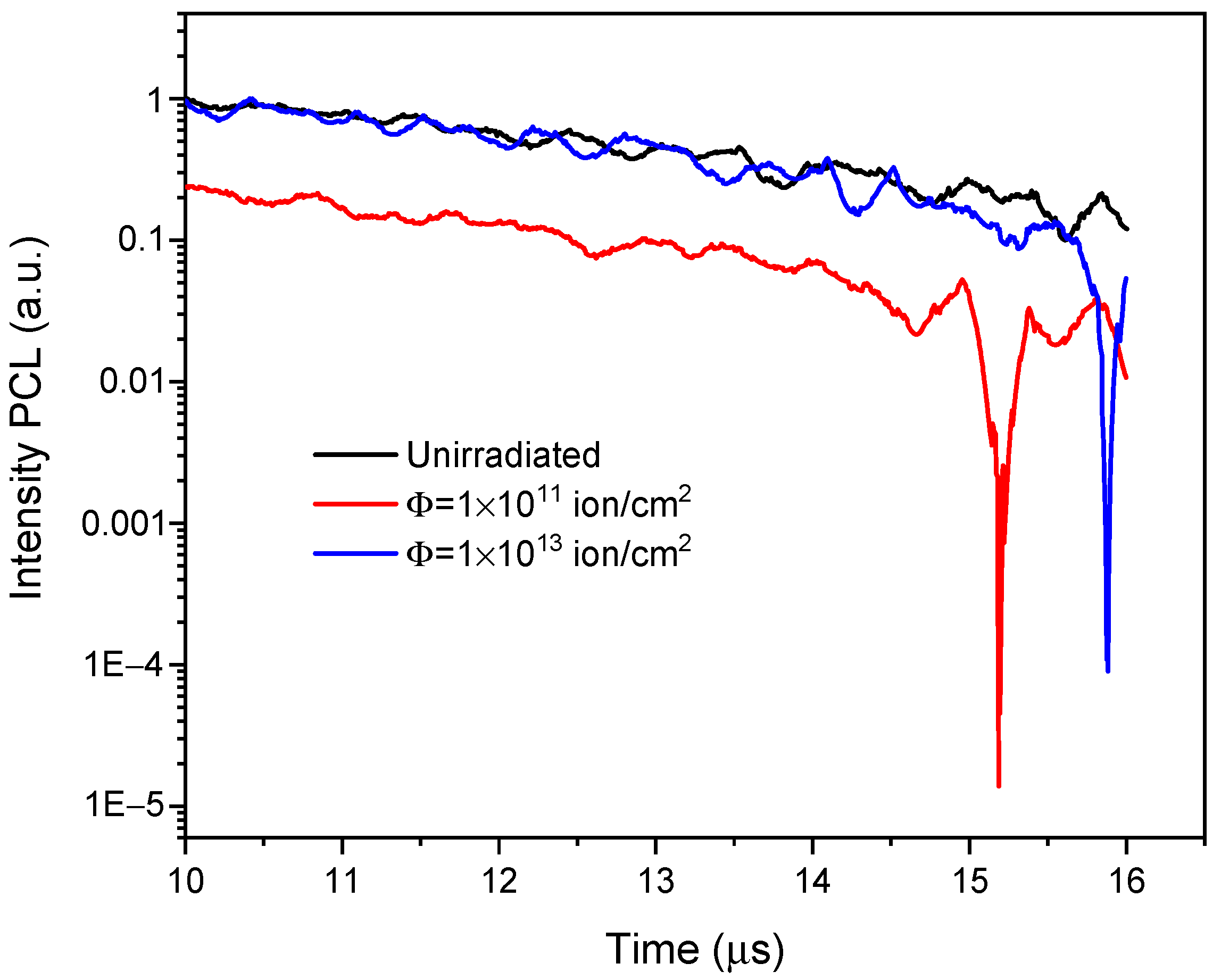

3.2. The Pulsed Cathodoluminescence (PCL)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Horst, A.; Joachim, D.; Sigrid, J.-B.; Manfred, S. Radiation Exposure and Image Quality in X-Ray Diagnostic Radiology. In Physical Principles and Clinical Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 2, p. 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbagwu, J. Theoretical investigation of dosimeter accuracy for linear energy transfer measurements in proton therapy: A comparative study of stopping power ratios. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 227, 112354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, Y.; Kai, T.; Ogawa, T.; Matsuya, Y.; Sato, T. Development of a model for evaluating the luminescence intensity of phosphors based on the PHITS track-structure simulation. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2024, 547, 165183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderloo, N.; Cufari, M.; Russell, L.; Johnson, T.M.; Vargas, J.; Foo, B.C.; Buschmann, B.I.; Dannhoff, S.G.; DeVault, A.; Evans, T.E.; et al. Image plate multi-scan response to fusion protons in the range of 1–14 MeV. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2024, 95, 093536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Mori, M.; Kotaki, H.; Onoda, S.; Yamada, K.; Kando, M. Measuring the sensitivity of imaging plates to keV carbon ions. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2024, 95, 123309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Kato, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Tanaka, M.; Okada, G.; Nakauchi, D.; Kawaguchi, N.; Yanagida, T. Optical and photostimulated luminescence properties of Eu:BaFBr translucent ceramics synthesized by SPS. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 15315–15319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezrukovs, V.; Konuhova, M.; Bezrukovs, D.; Berzins, A. Hydrogen Hydraulic Compression System for Refuelling Stations. Latv. J. Phys. Tech. Sci. 2022, 59 (Suppl. S3), 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, Y.; Sato, T.; Watanabe, K.; Ogawa, T.; Parisi, A.; Uritani, A. Theoretical and experimental estimation of the relative optically stimulated luminescence efficiency of an optical-fiber-based BaFBr:Eu detector for swift ions. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakrishna, K.; Dhanasekaran, A.; Yuvaraj, N.; Ajoy, K.C.; Venkatraman, B.; Jose, M.T. Improvement in Plastic Scintillator with Loading of BaFBr:Eu2;⁺ Radioluminescence Phosphor. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2021, 68, 1286–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.; Zimmermann, J.; McIntyre, G.; Wilkinson, C. Photostimulated luminescence properties of neutron image plates. Opt. Mater. 2016, 59, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeley, M. Neutron macromolecular crystallography. Crystallogr. Rev. 2009, 15, 157–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.G.; Yousuf, M.; Subramanian, N.; Pumiah, B.; Kasiviswanathan, K.V. Photostimulable luminescence: Physics and applications. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. 1997, 35, 699–708. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, H.; Satoh, M.; Matsubayashi, M. Study for a novel tomography technique using an imaging plate. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 1999, 424, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, A.; Kan’No, K.; Iwabuchi, Y.; Mori, N. Luminescence from self-trapped excitons in BaFCl/BaFBr solid solutions. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1996, 79, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, S.; Ruan, J.; Itoh, M.; Hashimoto, S.; Sakuragi, S. A new type of luminescence mechanism in large band-gap insulators: Proposal for fast scintillation materials. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 1990, 289, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadatal-Raduban, M.; Mui, L.V.; Yamashita, M.; Shibazaki, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Sarukura, N.; Yamanoi, K. Pressure-controlled luminescence in fast-response barium fluoride crystals. NPG Asia Mater. 2024, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eijk, C. Cross-luminescence. J. Lumin. 1994, 60–61, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirm, M.; Nagirnyi, V.; Vielhauer, S.; Feldbach, E. Relaxation and interaction of electronic excitations induced by intense ultra short light pulses in BaF2 scintillator. In Damage to VUV, EUV, and X-Ray Optics III, Proceedings of the 2011 SPIE Optics + Optoelectronics, Prague, Czech Republic, 18–21 April 2011; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, C.; Gabriel, A.; Lehmann, M.; Zemb, T.; Ne, F. Image plate neutron detector. In SPIE 1737, Neutrons, X Rays, and Gamma Rays: Imaging Detectors, Material Characterization Techniques, and Applications, Proceedings of the San Diego ‘92, San Diego, CA, USA, 2 February 1993; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niimura, N.; Karasawa, Y.; Tanaka, I.; Miyahara, J.; Takahashi, K.; Saito, H.; Koizumi, S.; Hidaka, M. An imaging plate neutron detector. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 1994, 349, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, F.; Castagna, J.-C.; Claustre, L.; Wilkinson, C.; Lehmann, M.S. Large area neutron and X-ray image-plate detectors for macromolecular biology. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 1997, 392, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, C.; Cowan, J.A.; Myles, D.A.A.; Cipriani, F.; McIntyre, G.J. VIVALDI—A thermal-neutron laue diffractometer for physics, chemistry and materials science. Neutron News 2002, 13, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosaki, M.; Nakamura, M.; Hirose, M.; Matsumoto, H. Application of heavy-ion microbeam system at Kyoto University: Energy response for imaging plate by single ion irradiation. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2011, 269, 3145–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batentschuk, M.; Winnacker, A.; Schwartz, K.; Trautmann, C. Storage efficiency of BaFBr:Eu2+ image plates irradiated by swift heavy ions. J. Lumin. 2007, 125, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaev, A.A.; Radzhabov, E.A. Single crystal growth of BaFBr:Eu storage phosphor with alkali impurities. J. Cryst. Growth 2005, 275, e775–e777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akilbekov, A.; Kenbayev, D.; Dauletbekova, A.; Polisadova, E.; Yakovlev, V.; Karipbayev, Z.; Shalaev, A.; Elsts, E.; Popov, A.I. The Effect of Fast Kr Ion Irradiation on the Optical Absorption, Luminescence, and Raman Spectra of BaFBr Crystals. Crystals 2023, 13, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.F.; Ziegler, M.D.; Biersack, J.P. SRIM—The stopping and range of ions in matter. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2010, 268, 1818–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akilbekov, A.; Kenbayev, D.; Dauletbekova, A.; Shalaev, A.; Akylbekova, A.; Aralbayeva, G.; Baimukhanov, Z.; Baizhumanov, M.; Elsts, E.; Popov, A.I. The Effect of 147 MeV 84Kr and 24.5 MeV 14N Ions Irradiation on the Optical Absorption, Luminescence, Raman Spectra and Surface of BaFBr Crystals. Crystals 2024, 14, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.G.; Lenus, A.J. X-ray excited optical luminescence studies on the system BaXY (X,Y = F, Cl, Br, I). Pramana—J. Phys. 2005, 65, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzhabov, E.A.; Egranov, A.V. Exciton emission in BaFBr and BaFCl crystals. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1994, 6, 5639–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, A.; Kan’NO, K.; Iwabuchi, Y.; Mori, N. Recombination luminescence from self-trapped excitons in BaFBr. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 1994, 91, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inerbaev, T.; Akilbekov, A.; Kenbayev, D.; Dauletbekova, A.; Shalaev, A.; Polisadova, E.; Konuhova, M.; Piskunov, S.; Popov, A.I. Color Centers in BaFBr Crystals: Experimental Study and Theoretical Modeling. Materials 2024, 17, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baetzold, R.C. Possibility of off-center-exciton formation in BaFBr. Phys. Rev. B 1989, 40, 3246–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundacker, S.; Pots, R.H.; Nepomnyashchikh, A.; Radzhabov, E.; Shendrik, R.; Omelkov, S.; Kirm, M.; Acerbi, F.; Capasso, M.; Paternoster, G.; et al. Vacuum ultraviolet silicon photomultipliers applied to BaF2 cross-luminescence detection for high-rate ultrafast timing applications. Phys. Med. Biol. 2021, 66, 114002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenbayev, D.; Sorokin, M.V.; El-Said, A.S.; Dauletbekova, A.; Saduova, B.; Aralbayeva, G.; Akilbekov, A.; Shablonin, E.; Bazarbek, A.-D. Creation and Stability of Color Centers in BaF2 Single Crystals Irradiated with Swift 132Xe Ions. Crystals 2025, 15, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Object | Ion | Energy, MeV | Fluence, Ions/cm2 | R, µm | Length, mm | Width, mm | Thickness, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaFBr | Unirr. | – | – | – | 10 | 9 | 1 |

| Kr | 147 | 1010 | 17.87 | 12 | 10 | 1 | |

| 1011 | 11 | 10 | 0.9 | ||||

| 1012 | 9 | 6 | 1 | ||||

| 1013 | 10 | 5 | 0.5 | ||||

| 1014 | 7 | 4 | 0.3 |

| Ion | (Φ), Ion/cm2 | (λ), nm | (τ), mks | (A) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ1 | τ2 | A1 | A2 | |||

| 84Kr | virgin | 295 | 0.057 | 0.541 | 2.841 | 0.116 |

| 1 × 1010 | 295 | 0.057 | 0.571 | 4.853 | 0.146 | |

| 1 × 1011 | 295 | 0.062 | 0.721 | 0.817 | 0.108 | |

| 1 × 1012 | 295 | 0.0478 | 0.266 | 0.274 | 0.065 | |

| 1 × 1013 | 290 | 0.392 | 1.985 | 4.093 | 2.551 | |

| 1 × 1014 | 310 | 0.059 | 0.467 | 0.454 | 0.125 | |

| Ion | (Φ), Ion/cm2 | (λ), nm | (τ), mks | (A) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ1 | τ2 | A1 | A2 | |||

| 84Kr | virgin | 300 | 0.397 | 3.908 | 6.172 | 14.659 |

| 1 × 1011 | 300 | 0.084 | 6.793 | 6.965 | 0.333 | |

| 1 × 1013 | 300 | 0.096 | 1.711 | 0.055 | 0.518 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kenbayev, D.; Akilbekov, A.; Dauletbekova, A.; Aralbayeva, G.; Saduova, B.; Knyazev, M. Luminescence of BaFBr and BaF2 Crystals Irradiated by Swift Krypton Ions. Crystals 2025, 15, 1027. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121027

Kenbayev D, Akilbekov A, Dauletbekova A, Aralbayeva G, Saduova B, Knyazev M. Luminescence of BaFBr and BaF2 Crystals Irradiated by Swift Krypton Ions. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1027. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121027

Chicago/Turabian StyleKenbayev, Daurzhan, Abdirash Akilbekov, Alma Dauletbekova, Gulnara Aralbayeva, Balzhan Saduova, and Madiyar Knyazev. 2025. "Luminescence of BaFBr and BaF2 Crystals Irradiated by Swift Krypton Ions" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1027. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121027

APA StyleKenbayev, D., Akilbekov, A., Dauletbekova, A., Aralbayeva, G., Saduova, B., & Knyazev, M. (2025). Luminescence of BaFBr and BaF2 Crystals Irradiated by Swift Krypton Ions. Crystals, 15(12), 1027. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121027