Plasmon Dispersion in Two-Dimensional Systems with Non-Coulomb Interaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory

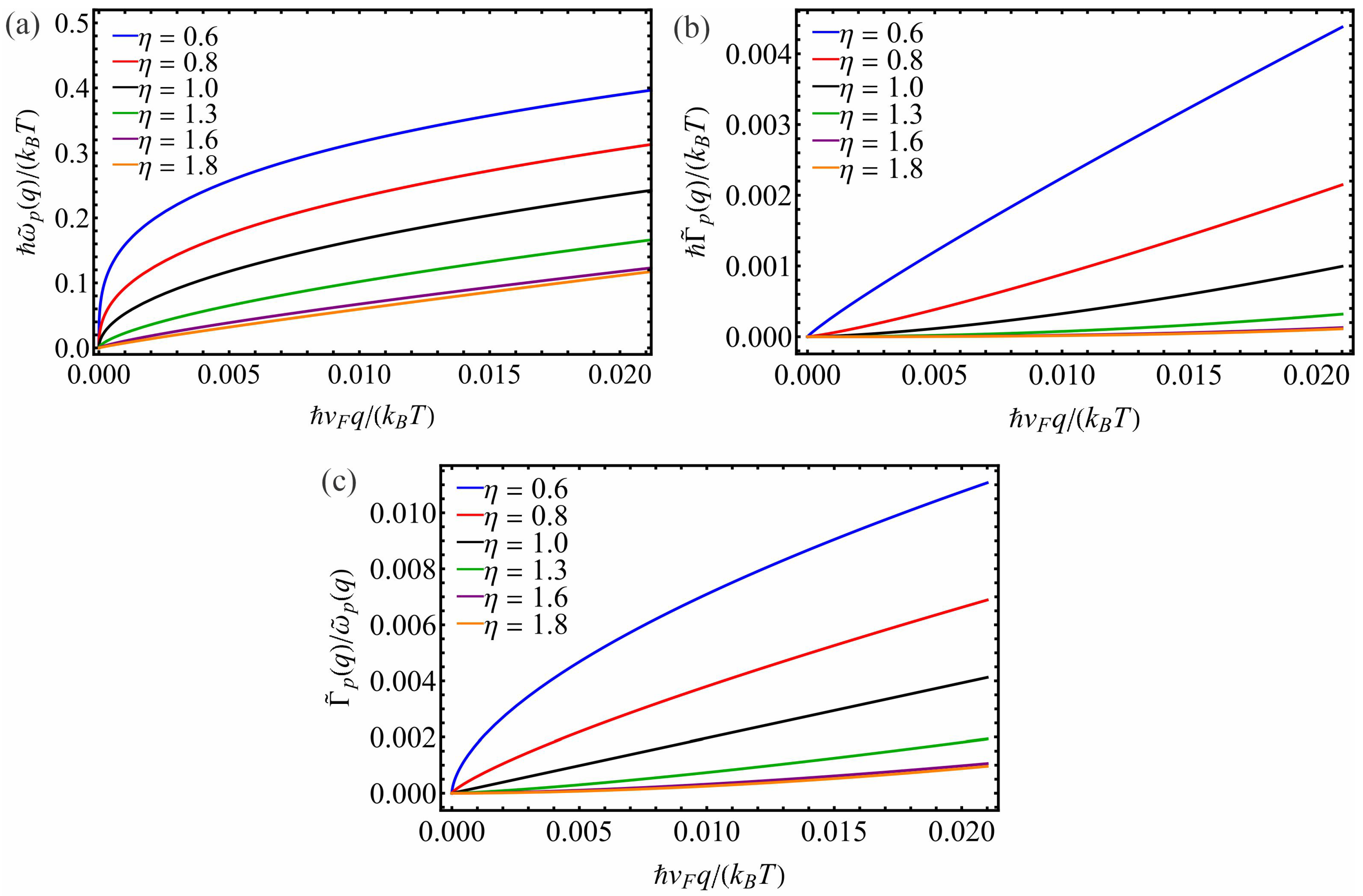

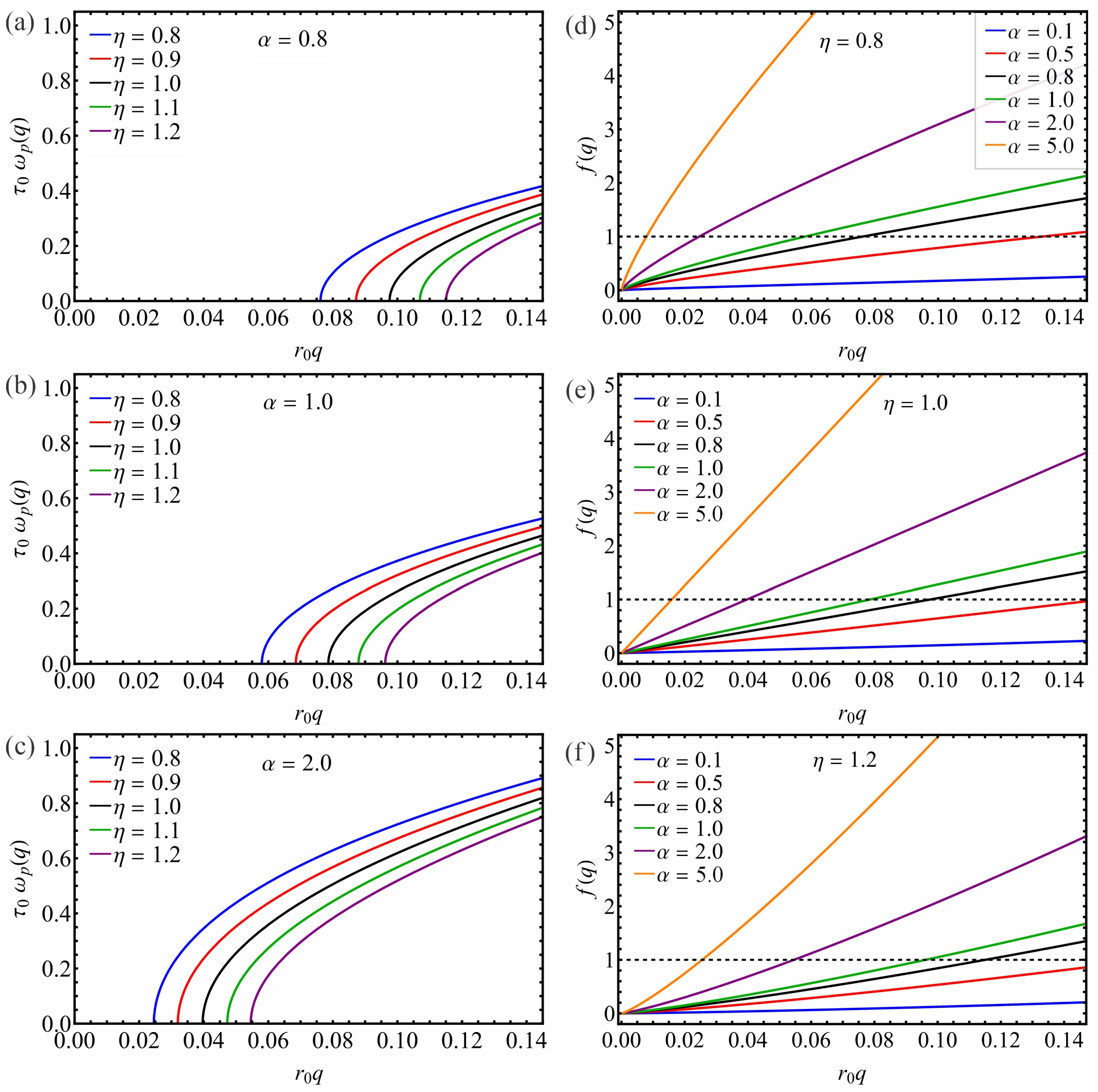

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pines, D. Elementary Excitations In Solids; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999; p. 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, G.; Vignale, G. Quantum Theory of the Electron Liquid; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bozhevolnyi, S.I. Coupling of Quantum Emitters to Plasmonic Nanoguides. In Quantum Plasmonics; Bozhevolnyi, S., Martin-Moreno, L., Garcia-Vidal, F., Eds.; Springer Series in Solid State Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, F. Polarizability of a Two-Dimensional Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967, 18, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunsch, B.; Stauber, T.; Sols, F.; Guinea, F. Dynamical polarization of graphene at finite doping. New J. Phys. 2006, 8, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Sarma, S.; Hwang, E.H. Collective Modes of the Massless Dirac Plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 206412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S. Plasmonics: Fundamentals and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Geng, B.; Horng, J.; Girit, C.; Martin, M.; Hao, Z.; Bechtel, H.A.; Liang, X.; Zettl, A.; Shen, Y.R.; et al. Graphene plasmonics for tunable terahertz metamaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Qiu, T.; Lu, W.; Ni, Z. Plasmons in graphene: Recent progress and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2013, 74, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tame, M.S.; McEnery, K.R.; Özdemir, Ş.K.; Lee, J.; Maier, S.A.; Kim, M.S. Quantum plasmonics. Nat. Phys. 2013, 9, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liu, K.; Sun, C. Plasmonics for Biosensing. Materials 2019, 12, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.H.; Das Sarma, S. Dielectric function, screening, and plasmons in two-dimensional graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 205418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorenko, A.N.; Polini, M.; Novoselov, K.S. Graphene plasmonics. Nat. Photonics 2012, 6, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Sarma, S.; Li, Q. Intrinsic plasmons in two-dimensional Dirac materials. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87, 235418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandurin, D.A.; Svintsov, D.; Gayduchenko, I.; Xu, S.G.; Principi, A.; Moskotin, M.; Tretyakov, I.; Yagodkin, D.; Zhukov, S.; Taniguchi, T.; et al. Resonant terahertz detection using graphene plasmons. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yu, R.; Teng, H.; Hu, D.; Chen, N.; Qu, Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; McLeod, A.S.; Alonso-González, P.; et al. Active control of micrometer plasmon propagation in suspended graphene. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Dubonos, S.V.; Firsov, A.A. Two-dimensional gas of massless Dirac fermions in graphene. Nature 2005, 438, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Neto, A.H.; Guinea, F.; Peres, N.M.R.; Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 109–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Sarma, S.; Adam, S.; Hwang, E.H.; Rossi, E. Electronic transport in two-dimensional graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 407–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, Y.W.; Stormer, H.L.; Kim, P. Experimental observation of the quantum Hall effect and Berry’s phase in graphene. Nature 2005, 438, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stander, N.; Huard, B.; Goldhaber-Gordon, D. Evidence for Klein Tunneling in Graphene p-n Junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 026807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakabayashi, K.; Dutta, S. Nanoscale and edge effect on electronic properties of graphene. Solid State Commun. 2012, 152, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffucci, A.; Miano, G. Electrical Properties of Graphene for Interconnect Applications. Appl. Sci. 2014, 4, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao-Zhe, L. Coulomb Screening and Plasmon Excitation in Graphene at Finite Temperature. Commun. Theor. Phys. 2009, 52, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyatkovskiy, P.K. Dynamical polarization, screening, and plasmons in gapped graphene. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 21, 025506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, A.; Schliemann, J. Dynamical current-current susceptibility of gapped graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 235409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.K.; Ashraf, S.S.Z.; Sharma, A.C. Finite temperature dynamical polarization and plasmons in gapped graphene. Phys. Status Solidi 2015, 252, 1817–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Sachdeva, R.; Agarwal, A. Dynamical polarizability, screening and plasmons in one, two and three dimensional massive Dirac systems. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 105701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brar, V.W.; Wickenburg, S.; Panlasigui, M.; Park, C.H.; Wehling, T.O.; Zhang, Y.; Decker, R.; Girit, i.m.c.b.u.; Balatsky, A.V.; Louie, S.G.; et al. Observation of Carrier-Density-Dependent Many-Body Effects in Graphene via Tunneling Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 036805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.; Andreev, G.O.; Bao, W.; Zhang, L.M.; McLeod, A.S.; Wang, C.; Stewart, M.K.; Zhao, Z.; Dominguez, G.; Thiemens, M.; et al. Infrared Nanoscopy of Dirac Plasmons at the Graphene–SiO2 Interface. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 4701–4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegenkamp, C.; Pfnür, H.; Langer, T.; Baringhaus, J.; Schumacher, H.W. Plasmon electron–hole resonance in epitaxial graphene. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2010, 23, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Badioli, M.; Alonso-González, P.; Thongrattanasiri, S.; Huth, F.; Osmond, J.; Spasenović, M.; Centeno, A.; Pesquera, A.; Godignon, P.; et al. Optical nano-imaging of gate-tunable graphene plasmons. Nature 2012, 487, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.; Rodin, A.S.; Andreev, G.O.; Bao, W.; McLeod, A.S.; Wagner, M.; Zhang, L.M.; Zhao, Z.; Thiemens, M.; Dominguez, G.; et al. Gate-tuning of graphene plasmons revealed by infrared nano-imaging. Nature 2012, 487, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Low, T.; Zhu, W.; Wu, Y.; Freitag, M.; Li, X.; Guinea, F.; Avouris, P.; Xia, F. Damping pathways of mid-infrared plasmons in graphene nanostructures. Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J.A.; Berweger, S.; O’Callahan, B.T.; Raschke, M.B. Phase-Resolved Surface Plasmon Interferometry of Graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 055502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, S.C.; Shie, C.S.; Chen, C.H.; Breitwieser, R.; Pai, W.W.; Guo, G.Y.; Chu, M.W. π-plasmon dispersion in free-standing graphene by momentum-resolved electron energy-loss spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 045418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, C.; Kim, U.J.; Choi, H. Two-dimensional Dirac plasmon-polaritons in graphene, 3D topological insulator and hybrid systems. Light. Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lin, Y.C.; Zhao, W.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Tang, D.M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Vapour–liquid–solid growth of monolayer MoS2 nanoribbons. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotekar-Patil, D.; Deng, J.; Wong, S.L.; Goh, K.E.J. Coulomb Blockade in Etched Single- and Few-Layer MoS2 Nanoribbons. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2019, 1, 2202–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, B.; Xie, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Jin, C. Deriving MoS2 nanoribbons from their flakes by chemical vapor deposition. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 255602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nüsse, S.; Haring Bolivar, P.; Kurz, H.; Klimov, V.; Levy, F. Carrier cooling and exciton formation in GaSe. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56, 4578–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Late, D.J.; Liu, B.; Luo, J.; Yan, A.; Matte, H.S.S.R.; Grayson, M.; Rao, C.N.R.; Dravid, V.P. GaS and GaSe Ultrathin Layer Transistors. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 3549–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybkovskiy, D.V.; Osadchy, A.V.; Obraztsova, E.D. Transition from parabolic to ring-shaped valence band maximum in few-layer GaS, GaSe, and InSe. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 235302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandurin, D.A.; Tyurnina, A.V.; Yu, G.L.; Mishchenko, A.; Zólyomi, V.; Morozov, S.V.; Kumar, R.K.; Gorbachev, R.V.; Kudrynskyi, Z.R.; Pezzini, S.; et al. High electron mobility, quantum Hall effect and anomalous optical response in atomically thin InSe. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Yu, S.; Yang, W.; Lou, W.k.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, D.; Chang, K. Current-induced spin polarization in monolayer InSe. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 245409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhang, D.; Yu, S.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Chang, K. Spin-charge conversion in InSe bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 155402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Huang, S.; Wang, C.; Luo, J.; Yan, H. The optical properties of few-layer InSe. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 060901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.S.; Stratakis, E. Recent Advances in 2D Metal Monochalcogenides. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahaman, M.; Aslam, M.A.; He, L.; Madeira, T.I.; Zahn, D.R.T. Plasmonic hot electron induced layer dependent anomalous Fröhlich interaction in InSe. Commun. Phys. 2021, 4, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M. Dynamical polarization function and plasmons in monolayer XSe (X = In, Ga). Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 155429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhou, C. Spin polarized quantum oscillations in monolayer InSe induced by magnetic field. Solid State Commun. 2022, 341, 114557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadanoff, L.P.; Martin, P.C. Hydrodynamic equations and correlation functions. Ann. Phys. 1963, 24, 419–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, G.F.; Quinn, J.J. Effects of diffusion on the plasma oscillations of a two-dimensional electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 1984, 29, 2321–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldart, D.; Das, A.; Gumbs, G. Plasmon dispersion relation for a disordered interacting quasi-two-dimensional electron gas. Solid State Commun. 1986, 60, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shegelski, M.R.A.; Geldart, D.J.W. Plasmons in disordered, two-component, quasi-two-dimensional electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 1989, 40, 3647–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tanatar, B.; Das, A.K. Effects of disorder on collective modes in single- and double-layer Bose systems. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1996, 8, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosu, I. Collective modes and disorder in two-dimensional systems. J. Optoelectron. Adv. M. 2007, 9, 2709–2712. [Google Scholar]

- Principi, A.; Vignale, G.; Carrega, M.; Polini, M. Impact of disorder on Dirac plasmon losses. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 121405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.V.; Popović, D. Critical Behavior of a Strongly Disordered 2D Electron System: The Cases of Long-Range and Screened Coulomb Interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 166401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, L.J.; Lin, P.V.; Jaroszyński, J.; Popović, D. Screening the Coulomb interaction leads to a prethermal regime in two-dimensional bad conductors. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, T.; Fishman, S.; Segev, M. Localisation of light in disordered lattices. Electron. Lett. 2008, 44, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Slade, T.J.; Hu, L.; Tan, X.Y.; Luo, Y.; Luo, Z.Z.; Xu, J.; Yan, Q.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Defect engineering in thermoelectric materials: What have we learned? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 9022–9054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaiser, M.; Zapperi, S. Disordered mechanical metamaterials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2023, 5, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C. Raman spectroscopy of graphene and graphite: Disorder, electron–phonon coupling, doping and nonadiabatic effects. Solid State Commun. 2007, 143, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banhart, F.; Kotakoski, J.; Krasheninnikov, A.V. Structural Defects in Graphene. ACS Nano 2010, 5, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, A.; Waldecker, L.; Zipfel, J.; Cho, Y.; Brem, S.; Ziegler, J.D.; Kulig, M.; Taniguchi, T.; Watanabe, K.; Malic, E.; et al. Dielectric disorder in two-dimensional materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 832–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, D.; Chae, S.H.; Ribeiro-Palau, R.; Hone, J. Disorder in van der Waals heterostructures of 2D materials. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bares, P.A.; Wen, X.G. Breakdown of the Fermi liquid due to long-range interactions. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48, 8636–8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stafiej, J.; di Caprio, D.; Badiali, J.P. A simple model to investigate the effects of non-Coulombic interactions on the structure of charged interfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109, 3607–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosu, I. Frequency Dependence of the Transport Scattering Time in Non-Fermi Liquids. J. Supercond. 2001, 14, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsnelson, M.I. Nonlinear screening of charge impurities in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 201401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, J.W.; Sawyer, B.C.; Keith, A.C.; Wang, C.C.J.; Freericks, J.K.; Uys, H.; Biercuk, M.J.; Bollinger, J.J. Engineered two-dimensional Ising interactions in a trapped-ion quantum simulator with hundreds of spins. Nature 2012, 484, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangara, R.; Stoltzfus, K.; York, M.R.; Swol, F.v.; Petsev, D.N. Coulombic and non-Coulombic effects in charge-regulating electric double layers. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 086331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabovich, A.M.; Li, M.S.; Szymczak, H.; Voitenko, A.I. Non-Coulombic behavior of electrostatic charge-charge interaction in three-layer heterostructures. J. Electrostat. 2019, 102, 103377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Muniz, M.C.; Panagiotopoulos, A.Z.; Car, R.; E, W. A deep potential model with long-range electrostatic interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 156, 124107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defenu, N.; Donner, T.; Macrì, T.; Pagano, G.; Ruffo, S.; Trombettoni, A. Long-range interacting quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2023, 95, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Bornet, G.; Bintz, M.; Emperauger, G.; Leclerc, L.; Liu, V.S.; Scholl, P.; Barredo, D.; Hauschild, J.; Chatterjee, S.; et al. Continuous symmetry breaking in a two-dimensional Rydberg array. Nature 2023, 616, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christakis, L.; Rosenberg, J.S.; Raj, R.; Chi, S.; Morningstar, A.; Huse, D.A.; Yan, Z.Z.; Bakr, W.S. Probing site-resolved correlations in a spin system of ultracold molecules. Nature 2023, 614, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzihovsky, L.; Toner, J. Coulomb universality. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 110, 014136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defenu, N.; Lerose, A.; Pappalardi, S. Out-of-equilibrium dynamics of quantum many-body systems with long-range interactions. Phys. Rep. 2024, 1074, 1–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddubny, A.; Miroshnichenko, A.; Slobozhanyuk, A.; Kivshar, Y. Topological Majorana States in Zigzag Chains of Plasmonic Nanoparticles. ACS Photonics 2014, 1, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Zhu, K.D. Surface Plasmon Enhanced Sensitive Detection for Possible Signature of Majorana Fermions via a Hybrid Semiconductor Quantum Dot-Metal Nanoparticle System. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Wu, H.W. Rabi splitting and optical Kerr nonlinearity of quantum dot mediated by Majorana fermions. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Máthé, L.; Kovács-Krausz, Z.; Botiz, I.; Grosu, I.; El Anouz, K.; El Allati, A.; Zârbo, L.P. Phonon-Assisted Tunneling through Quantum Dot Systems Connected to Majorana Bound States. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotov, V.N.; Uchoa, B.; Pereira, V.M.; Guinea, F.; Castro Neto, A.H. Electron-Electron Interactions in Graphene: Current Status and Perspectives. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012, 84, 1067–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudazzo, P.; Tokatly, I.V.; Rubio, A. Dielectric screening in two-dimensional insulators: Implications for excitonic and impurity states in graphane. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 085406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkelbach, T.C.; Hybertsen, M.S.; Reichman, D.R. Theory of neutral and charged excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 045318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernikov, A.; Berkelbach, T.C.; Hill, H.M.; Rigosi, A.; Li, Y.; Aslan, B.; Reichman, D.R.; Hybertsen, M.S.; Heinz, T.F. Exciton Binding Energy and Nonhydrogenic Rydberg Series in Monolayer WS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 076802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtade, E.; Semina, M.; Manca, M.; Glazov, M.M.; Robert, C.; Cadiz, F.; Wang, G.; Taniguchi, T.; Watanabe, K.; Pierre, M.; et al. Charged excitons in monolayer WSe2: Experiment and theory. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 085302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tuan, D.; Yang, M.; Dery, H. Coulomb interaction in monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 125308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; van Baren, J.; Taniguchi, T.; Watanabe, K.; Chang, Y.C.; Lui, C.H. Magnetophotoluminescence of exciton Rydberg states in monolayer WSe2. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 205420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P.; Malik, V.; Schechter, M. Effect of screening on the relaxation dynamics in a Coulomb glass. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 094208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene, V.M.; Lianu, I.; Grosu, I. Hartree-Fock approximation for non-Coulomb interactions in three and two-dimensional systems. Phys. Lett. A 2025, 529, 130064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máthé, L.; Grosu, I. Friedel oscillations in a two-dimensional electron gas and monolayer graphene with a non-Coulomb impurity potential. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2025, 173, 116328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, E.A. Fundamentals of Mathematical Physics; Dover Publications: Garden City, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Katsnelson, M.I. The Physics of Graphene; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Sarma, S.; Hwang, E.H. Dynamical response of a one-dimensional quantum-wire electron system. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 1936–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosu, I.; Tugulan, L. Plasmon dispersion in quasi-one- and one-dimensional systems with non-magnetic impurities. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2008, 40, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Principi, A.; Vignale, G.; Carrega, M.; Polini, M. Intrinsic lifetime of Dirac plasmons in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 195405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauber, T. Plasmonics in Dirac systems: From graphene to topological insulators. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2014, 26, 123201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafek, O. Anomalous Thermodynamics of Coulomb-Interacting Massless Dirac Fermions in Two Spatial Dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 216401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das Sarma, S.; Hwang, E.H.; Tse, W.K. Many-body interaction effects in doped and undoped graphene: Fermi liquid versus non-Fermi liquid. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 121406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, D.C.; Gorbachev, R.V.; Mayorov, A.S.; Morozov, S.V.; Zhukov, A.A.; Blake, P.; Ponomarenko, L.A.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Novoselov, K.S.; Guinea, F.; et al. Dirac cones reshaped by interaction effects in suspended graphene. Nat. Phys. 2011, 7, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.; Hwang, E.H.; Throckmorton, R.E.; Das Sarma, S. Effective field theory, three-loop perturbative expansion, and their experimental implications in graphene many-body effects. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 235431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linghua, K.; Baorong, Y.; Xiwei, H. Dispersion Relations of Longitudinal Plasmons in One, Two and Three Dimensional Electron Gas of Metals. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2007, 9, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Peng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.Y. Plasmon-enhanced light–matter interactions and applications. npj Comput. Mater. 2019, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babicheva, V.E. Optical Processes behind Plasmonic Applications. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallika, C.S.; Shwetha, M. Plasmonic Ring Resonator-Based Sensors: Design, Performance, and Applications. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 8423–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Máthé, L.; Lianu, I.; Calborean, A.; Grosu, I. Plasmon Dispersion in Two-Dimensional Systems with Non-Coulomb Interaction. Crystals 2025, 15, 985. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110985

Máthé L, Lianu I, Calborean A, Grosu I. Plasmon Dispersion in Two-Dimensional Systems with Non-Coulomb Interaction. Crystals. 2025; 15(11):985. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110985

Chicago/Turabian StyleMáthé, Levente, Ilinca Lianu, Adrian Calborean, and Ioan Grosu. 2025. "Plasmon Dispersion in Two-Dimensional Systems with Non-Coulomb Interaction" Crystals 15, no. 11: 985. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110985

APA StyleMáthé, L., Lianu, I., Calborean, A., & Grosu, I. (2025). Plasmon Dispersion in Two-Dimensional Systems with Non-Coulomb Interaction. Crystals, 15(11), 985. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110985