Reactions of the Uranyl Ion and a Bulky Tetradentate, “Salen-Type” Schiff Base: Synthesis and Study of Two Mononuclear Complexes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Microanalyses

2.3. Conductivity Measurements

2.4. Infrared Spectra

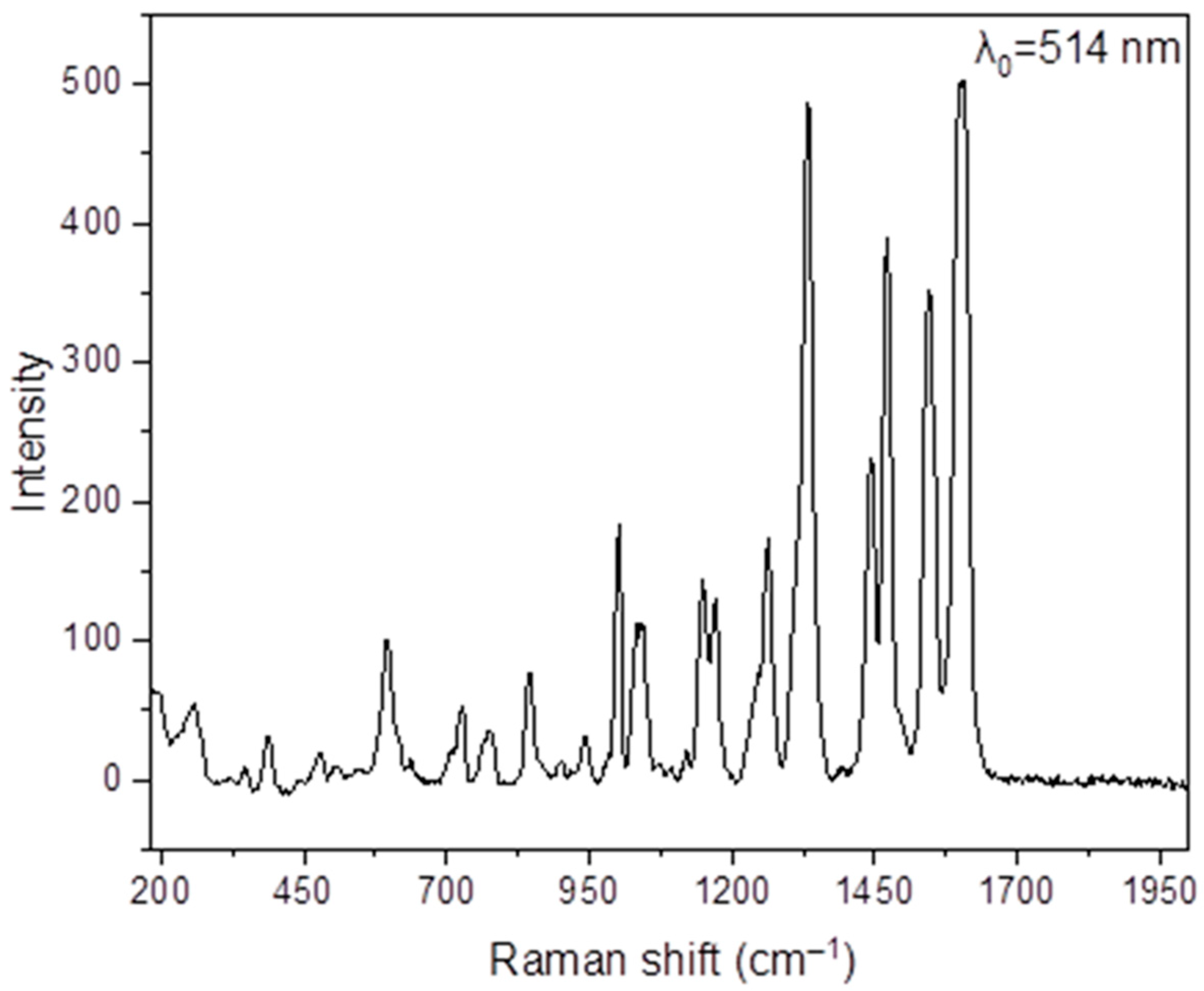

2.5. Raman Spectra

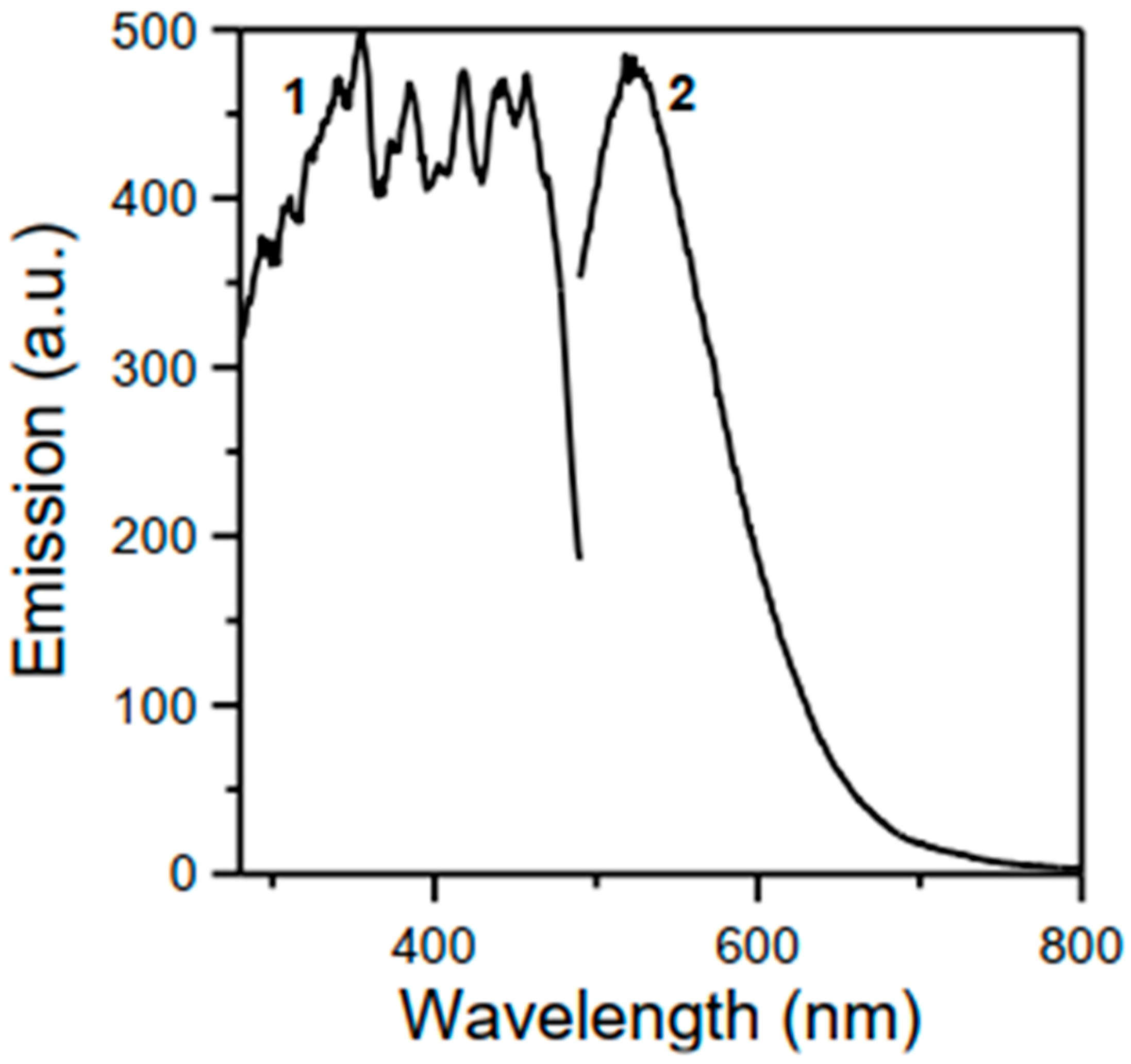

2.6. Photoluminescence Experiments

2.7. NMR Spectra

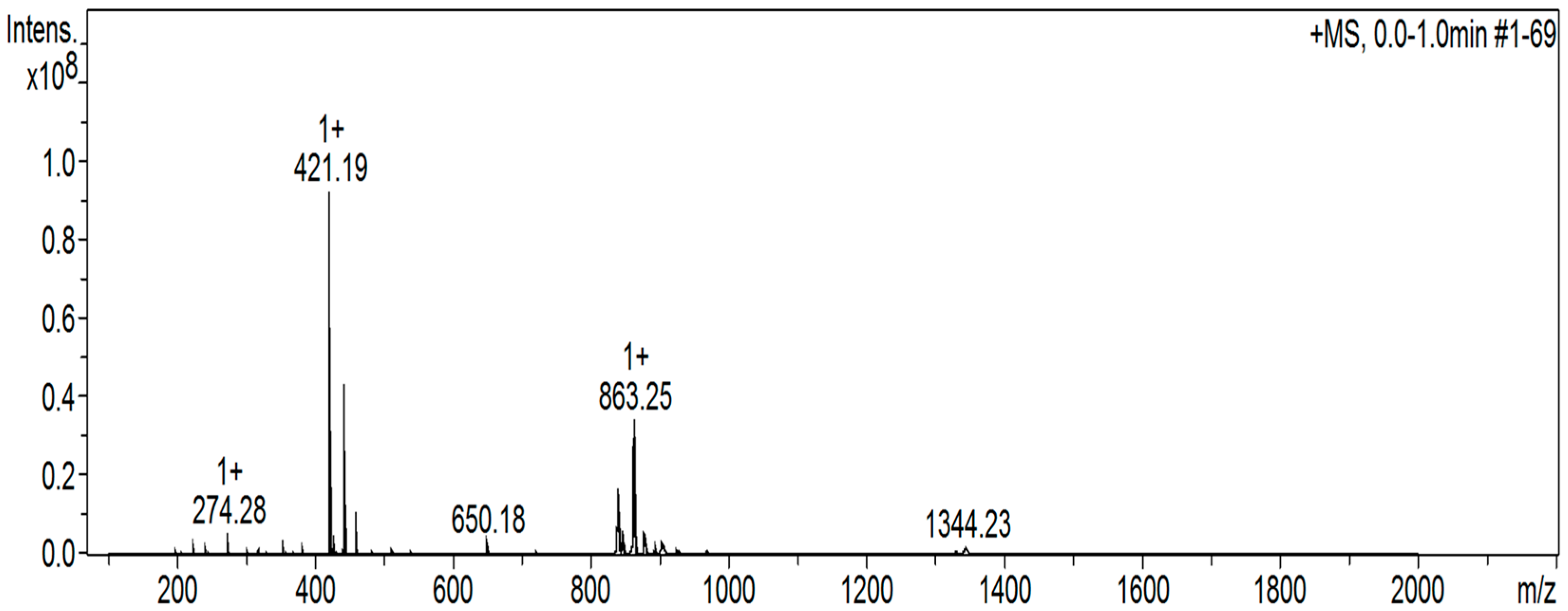

2.8. Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectra

2.9. Ultraviolet-Visible Spectra

2.10. Synthetic Procedures

2.11. Single-Crystal X-Ray Crystallography

2.12. Powder X-Ray Diffraction

3. Results and Discussion

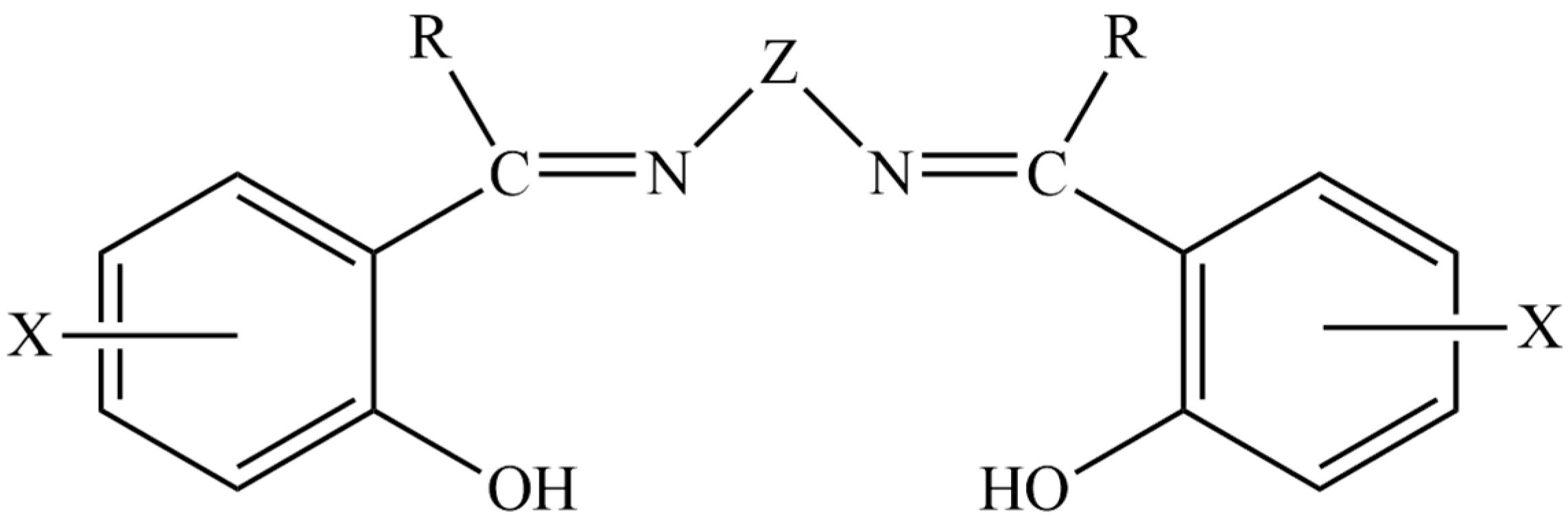

3.1. Synthetic and Spectroscopic Comments for the Free Ligand H2L

3.2. Isolation of a New Polymorph (Polymorph B) of H2L

3.3. Comments Concerning the Preparation of the Uranyl Complexes 1 and 2·DMF

3.4. Description of the Crystal Structure of H2L (Polymorph B) and Comparison with Polymorph A; Powder X-Ray Diffraction Pattern of the Crude Product

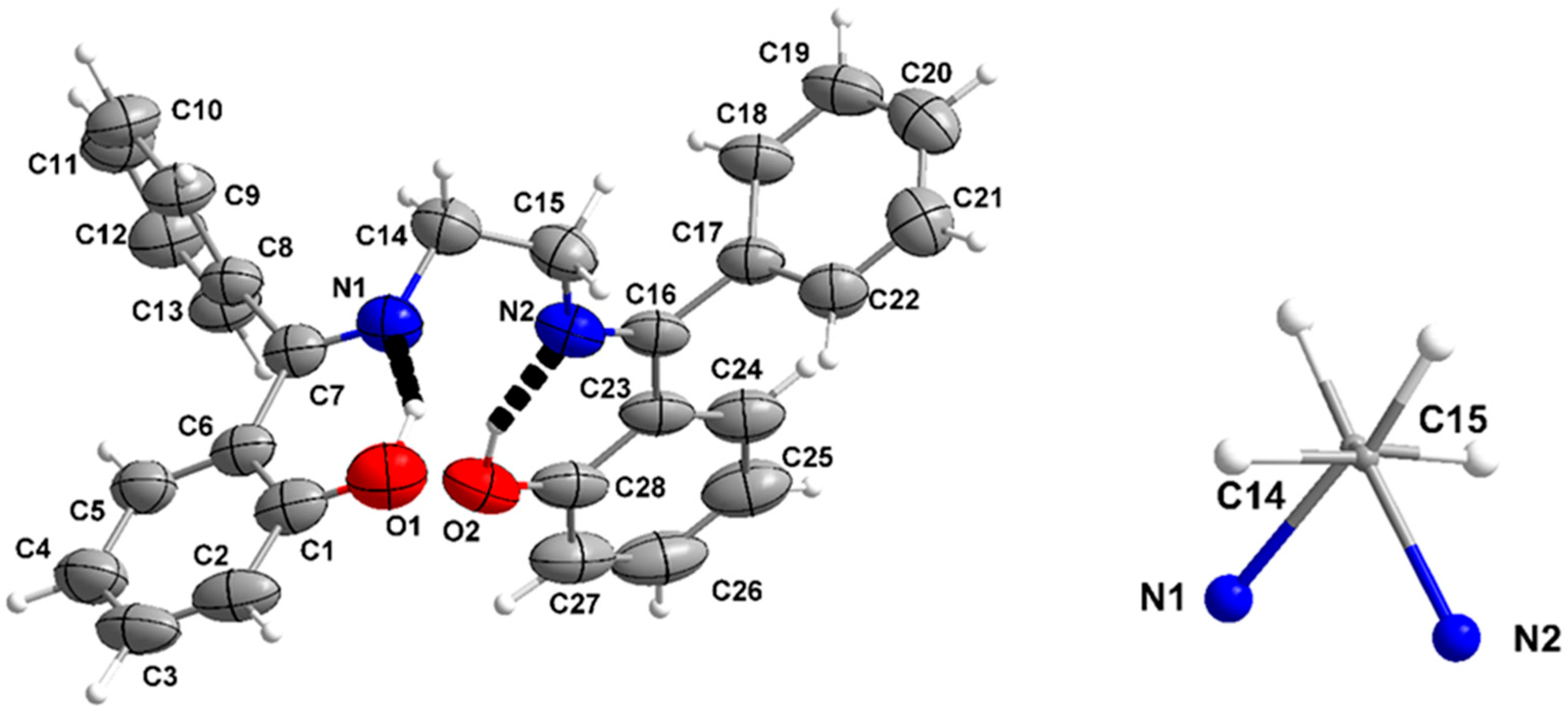

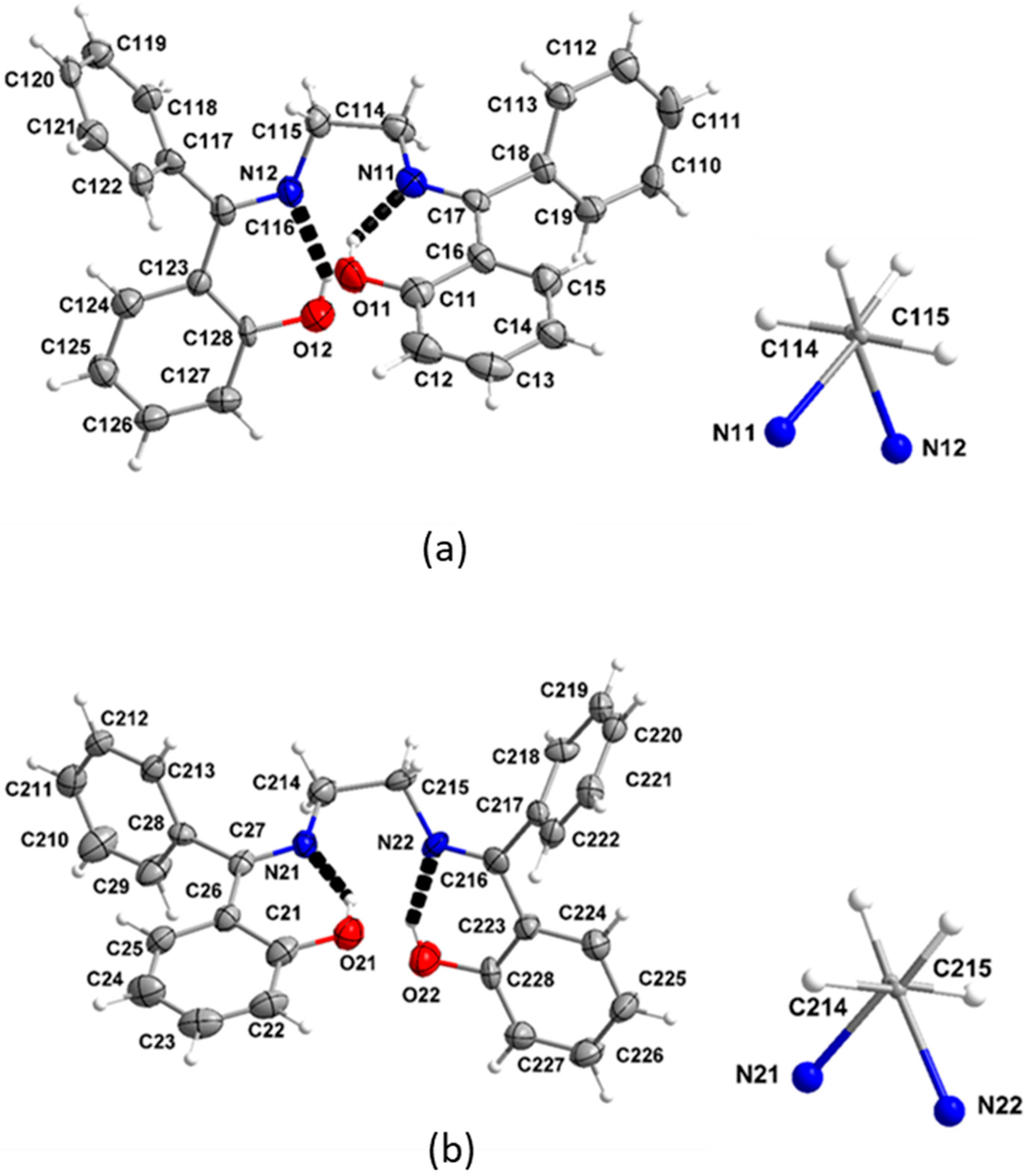

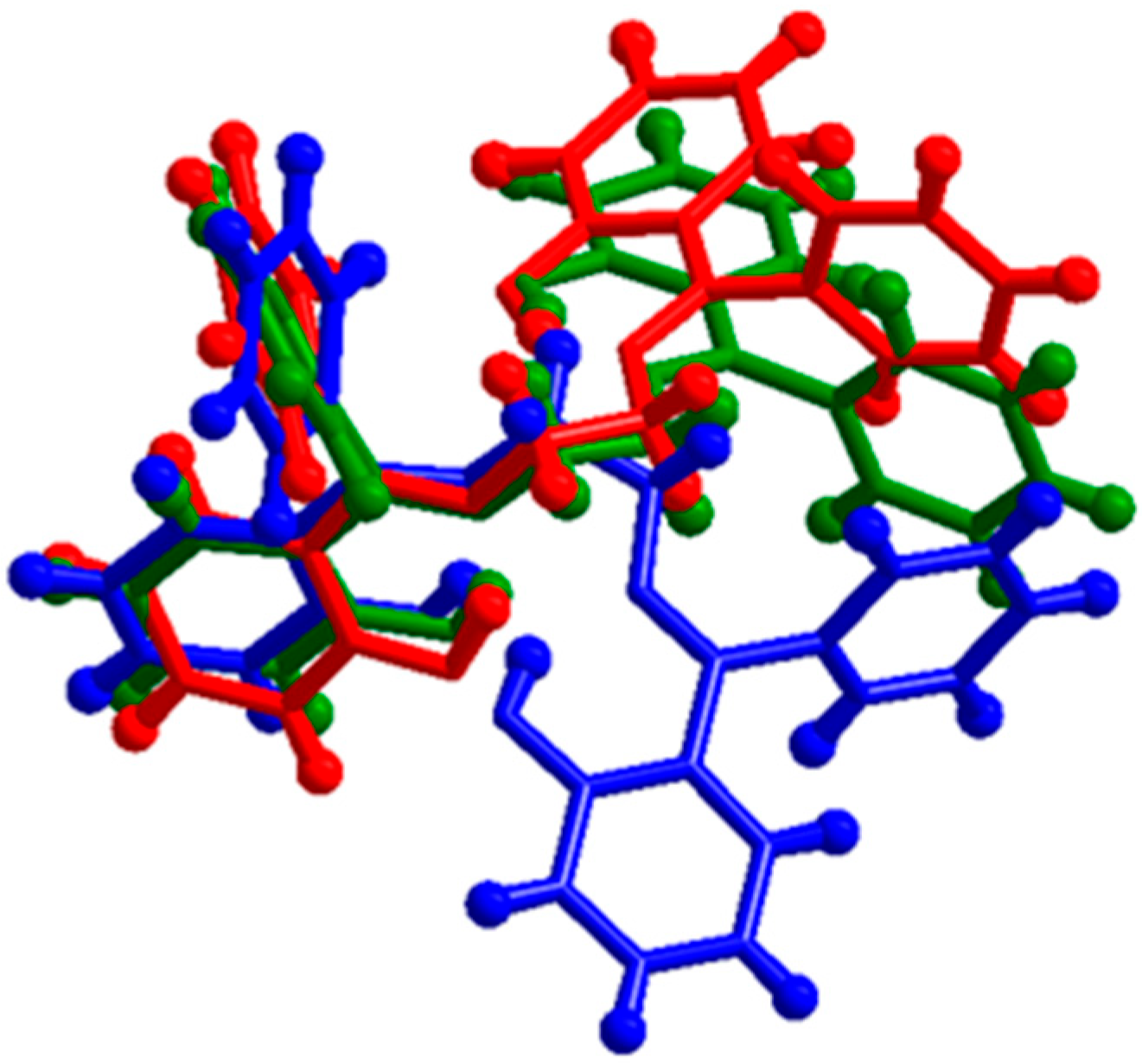

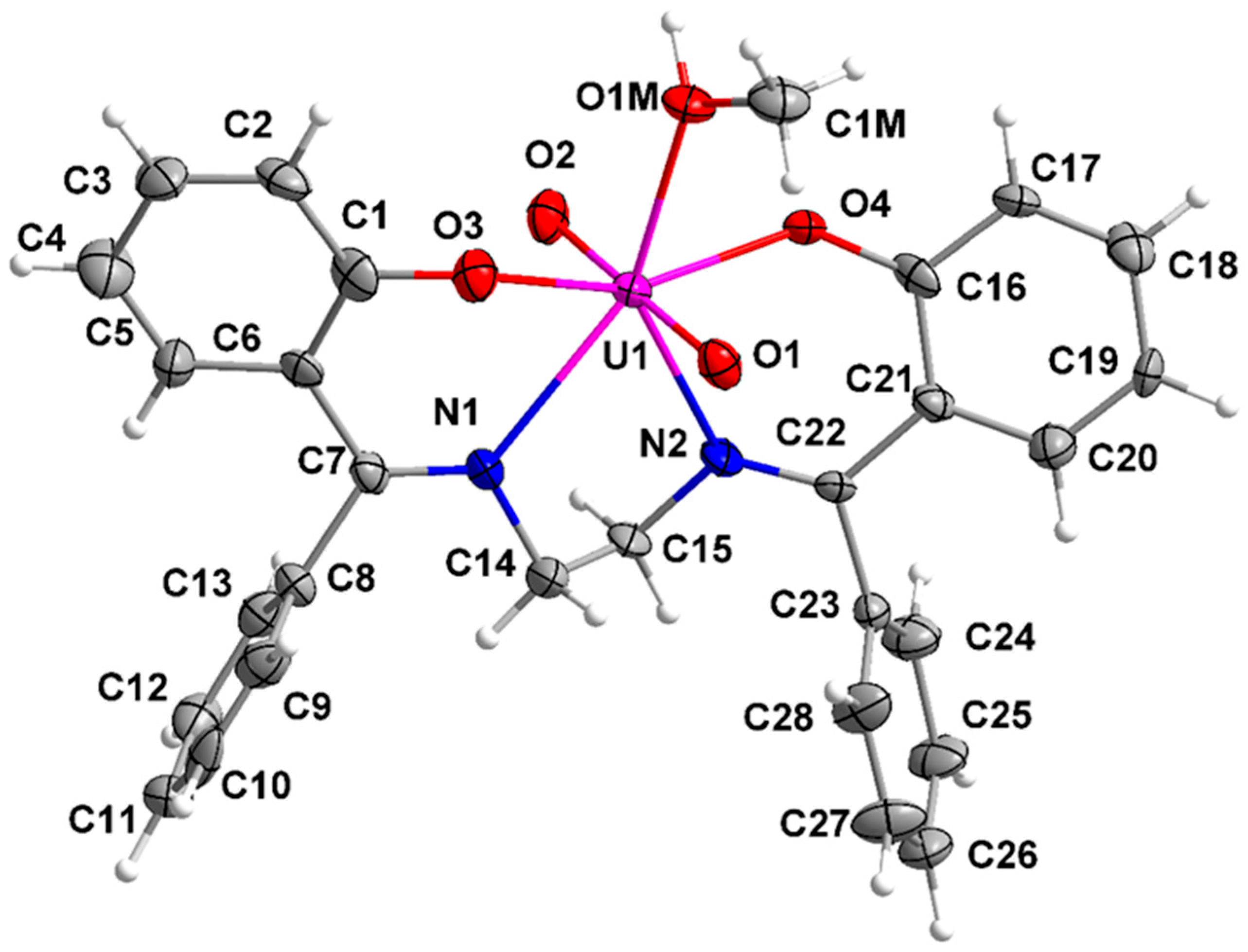

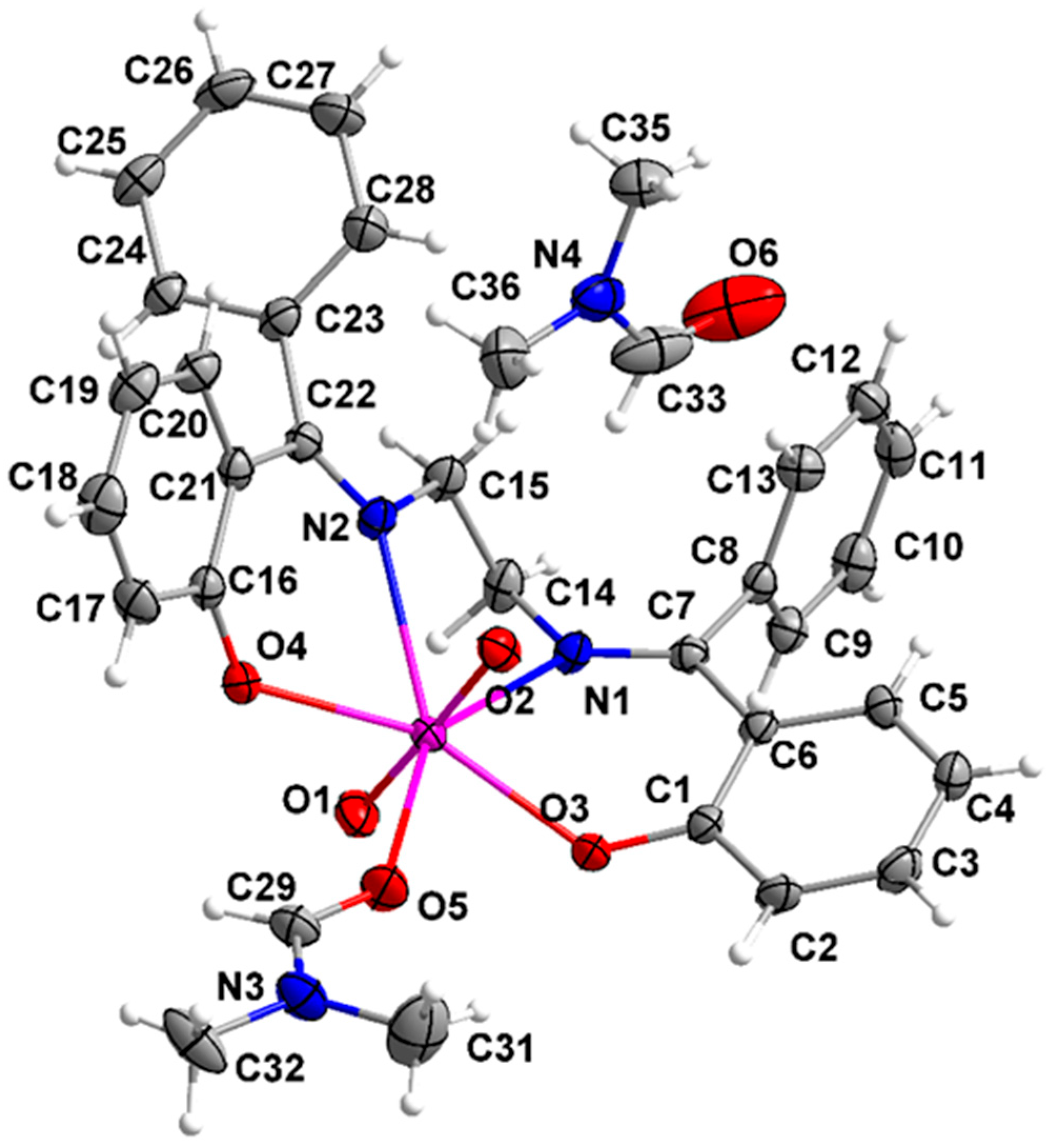

3.5. Description of the Molecular Structures of Complexes 1 and 2·DMF

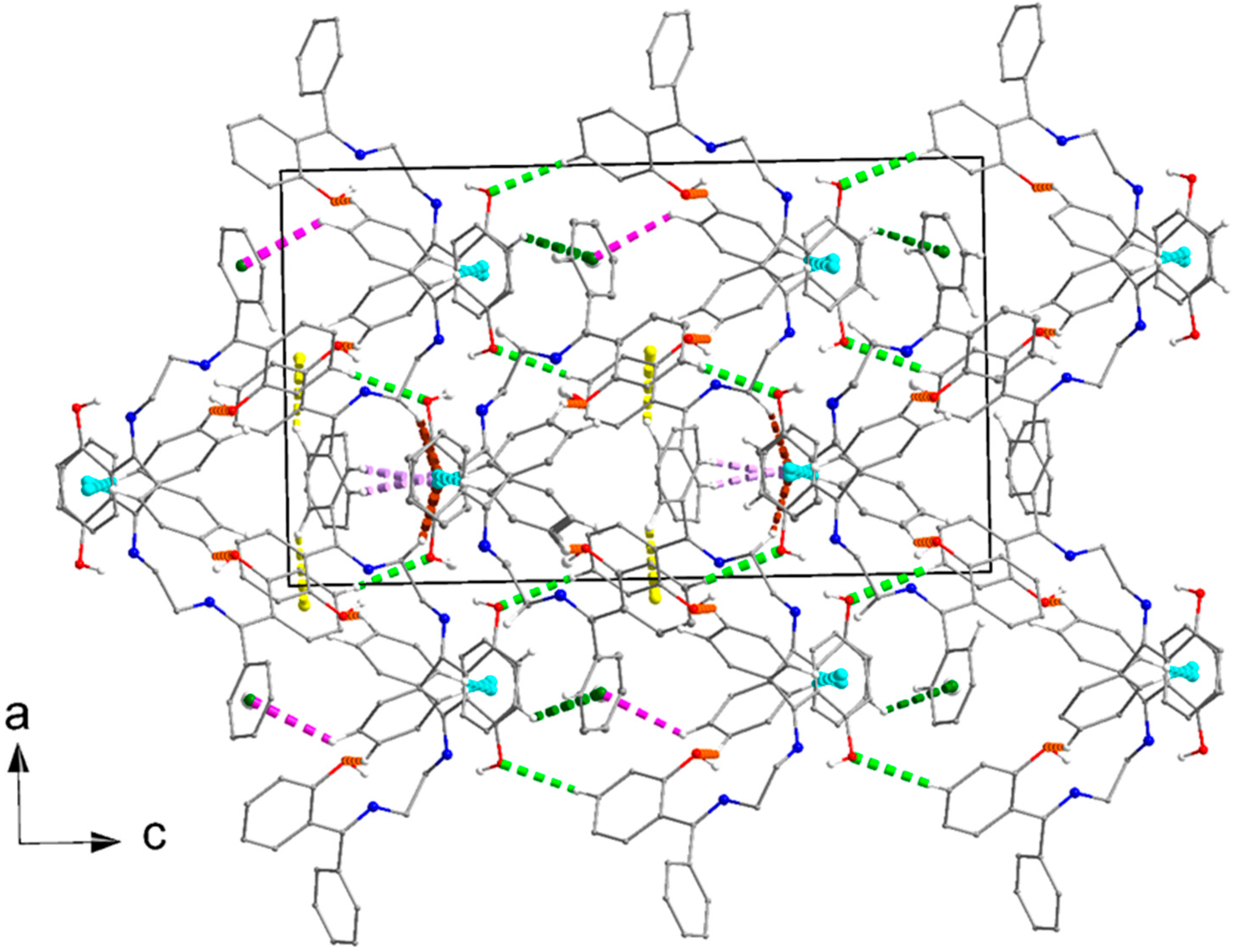

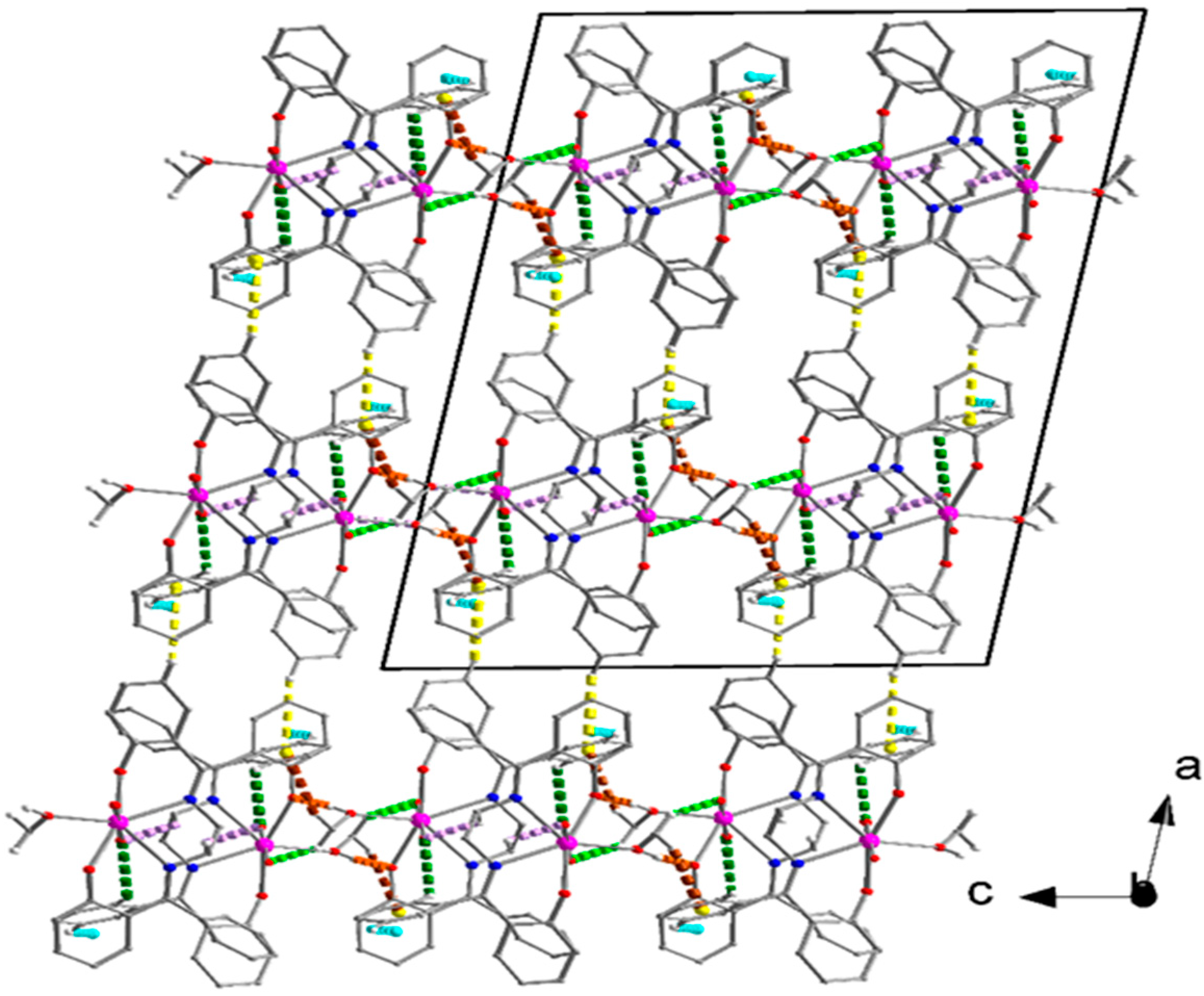

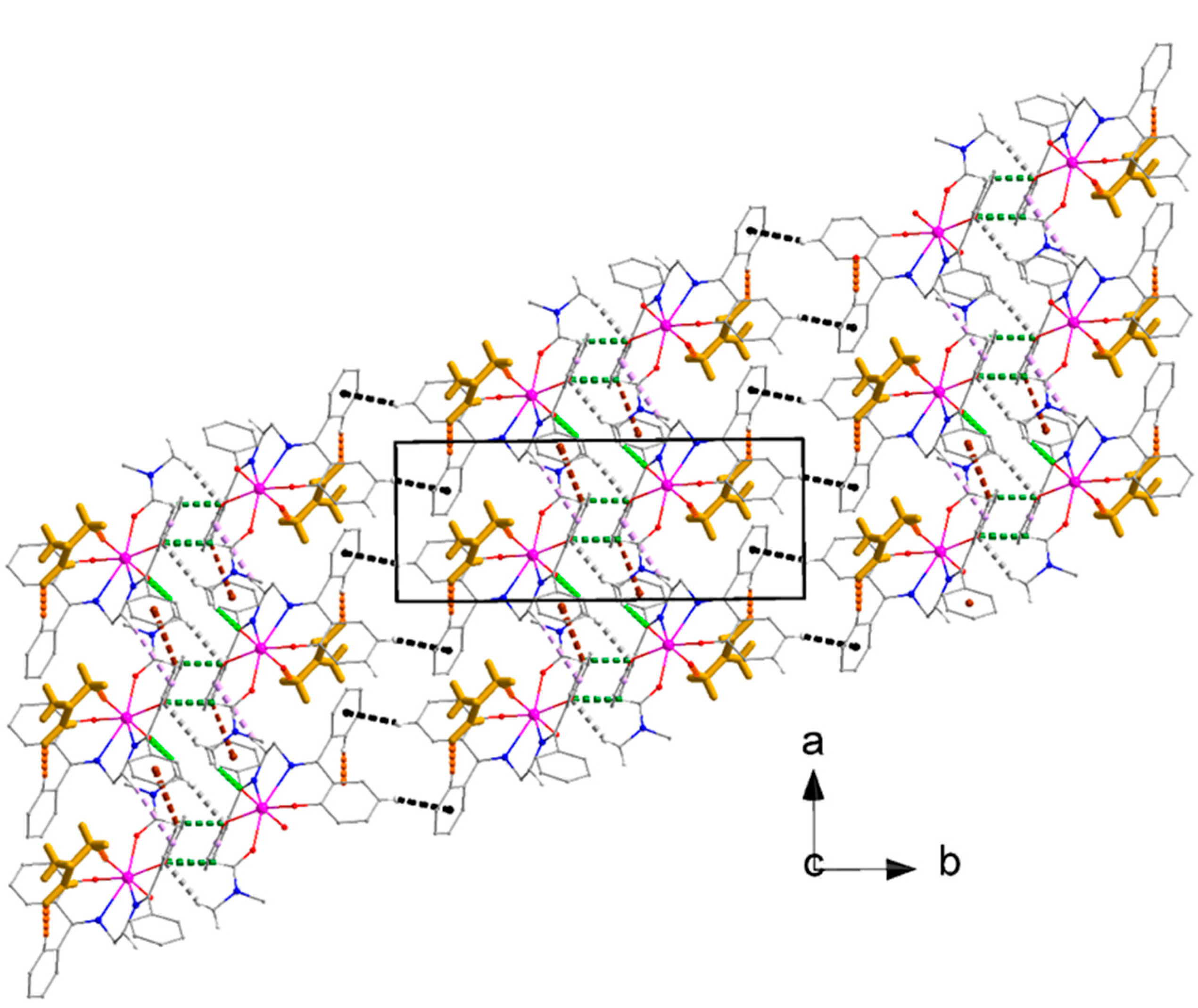

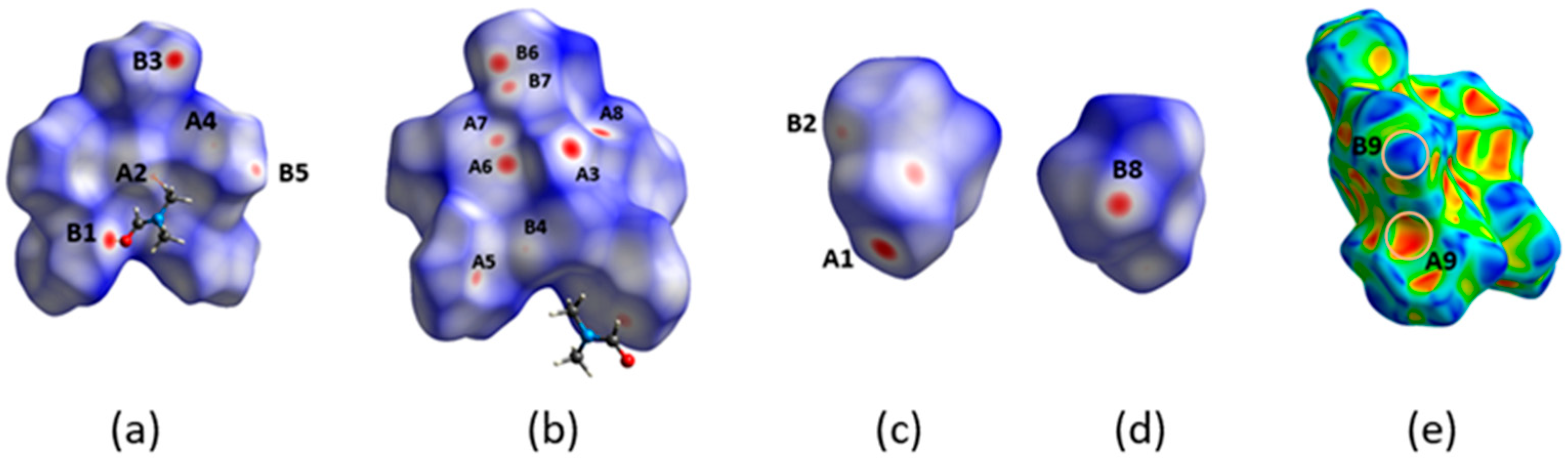

3.6. Supramolecular Features in the Crystal Structures of 1 and 2·DMF

3.7. Spectroscopic Characterization of 1 and 2·DMF in the Solid State

3.8. Solution Behavior of the Two Uranyl Complexes

4. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaltsoyannis, N.; Liddle, S.T. Catalyst: Nuclear Power in the 21st Century. Chem 2016, 1, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, C.J.; Neu, M.P.; Boukhalfa, H.; Gutowski, K.E.; Bridges, N.J.; Rogers, R.D. The Actinides. In Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II; McCleverty, J.A., Meyer, T.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 3, pp. 189–330. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, J.C.; Czerwinski, K.; Francesconi, L. Preface: Forum on Aspects of Inorganic Chemistry Related to Nuclear Energy. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 3405–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, S.T. The Renaissance of Non-Aqueous Uranium Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 8604–8641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, S.T. Progress in Nonaqueous Molecular Uranium Chemistry: Where to Next? Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 9366–9384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eralie, D.M.T.; Ducilon, J.; Gorden, A.E.V. Uranium Chemistry: Identifying the Next Frontiers. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoureas, N.; Vagiakos, I. Recent Advances in Low Valent Thorium and Uranium Chemistry. Inorganics 2024, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barluzzi, L.; Giblin, S.R.; Mansikkamäki, A.; Layfield, R.A. Identification of Oxidation State +1 in a Molecular Uranium Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 18229–18233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Housecroft, C.E.; Sharpe, A.G. Inorganic Chemistry, 5th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2018; pp. 1053–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Tsantis, S.T.; Iliopoulou, M.; Tzimopoulos, D.I.; Perlepes, S.P. Synthetic and Structural Chemistry of Uranyl-Amidoxime Complexes: Technological Implications. Chemistry 2023, 5, 1419–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoh, S.O.; Bondarevsky, G.D.; Karpus, J.; Cui, Q.; He, C.; Spezia, R.; Gagliardi, L. UO22+ uptake by proteins: Understanding the binding features of the super uranyl protein and design of a protein with higher affinity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17484–17494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Olds, T.; Stemiczuk, M.; Burns, P.C. Copper(I) and Copper(II) Uranyl Heterometallic Hybrid Materials. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 7993–7998. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Silver, M.A.; Liu, W.; Duan, T.; Yin, X.; Chen, L.; Diwu, J.; Chai, Z.; Wang, S. Tunable 4f/5f Bimodal Emission in Europium-Incorporated Uranyl Coordination Polymers. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, N.; Sethi, S. Unprecedented Catalytic Behavior of Uranyl(VI) Compounds in Chemical Reactions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobeck, H.L.; Isner, J.K.; Burns, P.C. Transformation of Uranyl Peroxide Studtite [(UO2(O2)(H2O)2](H2O)2 to a Soluble Nanoscale Cage Cluster. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 6781–6789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrowfield, J.; Thuery, P. Uranyl Ion Complexes of Polycarboxylates: Steps towards Isolated Photoactive Cavities. Chemistry 2020, 2, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.; Chen, F.-Y.; Gao, C.-Y.; Tian, H.R.; Pan, Q.-J.; Sun, Z.-M. Porous anionic uranyl-organic networks for highly efficient Cs+ adsorption and investigation of the mechanism. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 4419–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Hu, B.; Cai, Y.; Yuan, L.; Feng, W. Selective Complexation and Separation of Uranium(IV) from Thorium(IV) with New Tetradentate N,O-Hybrid Diamide Ligands: Synthesis, Extraction, Spectroscopy, and Crystallographic Studies. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 4922–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abney, C.W.; Mayes, R.T.; Saito, T.; Dai, S. Materials for the Recovery of Uranium from Seawater. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13935–14013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsantis, S.T.; Lada, Z.G.; Skiadas, S.G.; Tzimopoulos, D.I.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Psycharis, V.; Perlepes, S.P. Understanding the Selective Extraction of the Uranyl Ion from Seawater with Amidoxime-Functionalized Materials: Uranyl Complexes of Pyrimidine-2-amidoxime. Inorganics 2024, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hamon, J.-R. Recent developments in penta-, hexa- and heptadentate Schiff base ligands and their metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 389, 94–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Molina, R.; Mederos, A. Acyclic and Macrocyclic Schiff Base Ligands. In Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II; McCleverty, J.A., Meyer, T.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 441–446. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, S. Advancement in stereochemical aspects of Schiff base metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999, 190, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.C.; Sutar, A.K. Catalytic activities of Schiff base transition metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 1420–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J. Luminescent Schiff-Base Lanthanide Single-Molecule Magnets. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, E.C. Metals and Ligands Reactivity; VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1996; Volume 135–182, pp. 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gisbert, R.J. Coordination Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2008; Volume 133, p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzi, P.G. Metal-salen Schiff base complexes in catalysis. Practical aspects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004, 33, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, L.; Forni, A.; Righetto, S.; Pasini, A. Push-pull unsymmetrical substitution in nickel(II) complexes with tetradentate N2O2 Schiff base ligands. Synthesis, structures and linear-nonlinear optical studies. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 11217–11234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulou, K.I.; Terzis, A.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Psycharis, V.; Escuer, A.; Perlepes, S.P. Ni20 “bowls” from the use of tridentate Schiff bases. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 5615–5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camp, C.; Guidal, V.; Biswas, B.; Pécaut, J.; Dubois, L.; Mazzanti, M. Multielectron redox chemistry of lanthanide Schiff-base complexes. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 2433–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pu, N.; Li, Y.; Wei, P.; Sun, T.; Xiao, C.; Cheng, J.; Xu, C. Selective Separation and Complexation of Trivalent Actinide and Lanthanide by a Tetradentate Soft-Hard Donor Ligand: Solvent Extraction, Spectroscopy, and DFT Calculations. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 4420–4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costamagna, J.; Vargas, J.; Latorre, R.; Alvarado, A.; Mena, G. Coordination compounds of copper, nickel and iron with Schiff bases derived from hydroxynaphthaldehydes and salicylaldehydes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1992, 119, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, F.A.; Wilkinson, G.; Murillo, C.A.; Bochmann, M. Advanced Inorganic Chemistry, 6th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 375, p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- Tsantis, S.T.; Tzimopoulos, D.I.; Holynska, M.; Perlepes, S.P. Oligonuclear Actinoid Complexes with Schiff Bases as Ligands-Older Achievements and Recent Progress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costisor, O.; Linert, W. 4f and 5f Metal Ion Directed Schiff Condensation. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 24, 61–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, M.R.; Maurya, R.C. Coordination Chemistry of Schiff Base Complexes of Uranium. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 15, 1–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudkevich, D.M.; Verboom, W.; Brzozka, Z.; Palys, M.J.; Stauthamer, W.P.R.V.; van Hummel, G.J.; Franken, S.M.; Harkema, S.; Engbersen, J.F.J.; Reinhoudt, D.N. Functionalized UO2 salenes: Neutral receptors for anions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 4341–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Axel Castelli, V.; Cort Dalla, A.; Mandolini, L. Supramolecular catalysis of 1,4-thiol addition by salophen-uranyl complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 12688–12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.K.; Chakravorty, V. Extraction of uranium(VI) with binary mixtures of a quadridentate Schiff base and various neutral donors. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 1998, 227, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.A.; Bustillos, C.G.; Copping, R.; Scott, B.L.; May, I.; Nilsson, M. Challenging conventional f-element separation chemistry-reversing uranyl(VI)/lanthanide(III) solvent extraction selectivity. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 8670–8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowie, B.E.; Purkins, J.M.; Austin, J.; Love, J.B.; Arnold, P.L. Thermal and Photochemical Reduction and Functionalization Chemistry of the Uranyl Dication, [UVIO2]2+. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10595–10637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeyama, T.; Tsushima, S.; Gericke, R.; Duckworth, T.M.; Kaden, P.; März, J.; Takao, K. A Series of AnVIO22+ Complexes (An = U, Np, Pu) with N3O2-Donating Schiff-Base Ligands: Systematic Trends in the Molecular Structures and Redox Behavior. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamm, B.E.; Windorff, C.J.; Celis-Barros, C.; Marsh, M.L.; Albrecht-Schmitt, T.E. Synthesis, Spectroscopy and Theoretical Details of Uranyl Schiff-Base Coordination Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharara, M.S.; Tonks, S.A.; Gorden, A.E.V. Uranyl stabilized Schiff base complex. Chem. Commun. 2007, 4006–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazra, D.K.; Dinda, S.; Helliwell, M.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Mukherjee, M. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization and X-ray structure analyses of two uranyl complexes. Z. Kristallogr. 2009, 224, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.J.; Junk, P.C.; Smith, M.K. The effect of coordinated solvent ligands on the solid-state structures of compounds involving uranyl nitrate and Schiff bases. Polyhedron 2002, 21, 2421–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandoli, G.; Clemente, D.A.; Croatto, U.; Vidali, M.; Vigato, P.A. Crystal and Molecular Structure of [N,N′-Ethylenebis(salicylideneiminato)](methanol)dioxouranium. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton 1973, 2331–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustillos, C.G.; Hawkins, C.A.; Copping, R.; Reilly, S.D.; Scott, B.L.; May, I.; Nilsson, M. Complexation of High-Valency Mid-Actinides by a Lipophilic Schiff Base Ligand. Synthesis, Structural Characterization and Progress toward Selective Extraction. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 3559–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corden, J.P.; Errington, W.; Moore, P.; Wallbridge, M.G.H. Two Schiff Base Ligands Derived from 1,2-Diaminoethane. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 1997, 53, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K.; Michaud, P.; Kochi, J.K. Epoxidation of Olefins with Cationic (salen)MnIII Complexes. The Modulation of Catalytic Activity by Substituents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 2309–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.H.; Lim, K.S.; Ryu, D.W.; Yoon, S.M.; Suh, B.J.; Hong, C.S. Synthesis, Structures and Magnetic Properties of End-to-End Azide-Bridged Manganese(III) Chains: Elucidation of Direct Magnetostructural Correlation. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 7936–7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Harada, A.; Ohba, S.; Sakamoto, M.; Nishida, Y. Chemical mechanism of dioxygen activation by manganese(III) Schiff base compound in the presence of aliphatic aldehydes. Polyhedron 1997, 16, 2553–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsantis, S.T.; Bekiari, V.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Tzimopoulos, D.I.; Psycharis, V.; Perlepes, S.P. Dioxidouranium(VI) complexes with Schiff bases possessing an ONO donor set: Synthetic, structural and spectroscopic studies. Polyhedron 2018, 152, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsantis, S.T.; Lada, Z.G.; Tzimopoulos, D.I.; Bekiari, V.; Psycharis, V.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Perlepes, S.P. Two different coordination modes of the Schiff base derived from ortho-vanillin and 2-(2-aminomethyl)pyridine in a mononuclear uranyl complex. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crystalclear; Rigaku: The Woodlands, TX, USA, 2005.

- Shedrick, G.M. A Short History of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond-Crystal and Molecular Structure Visualization, Version 3.1; Crystal Impact: Bonn, Germany, 2018.

- Dollish, F.R.; Fateley, W.G.; Bentley, F.F. Characteristic Raman Frequencies of Organic Compounds; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 134–137. [Google Scholar]

- Szarlan, B.; Robaszkiewicz, J.; Pawluc, P.; Kubicki, M.; Zaranek, M. Salen-type nickel(II) complexes for distinct selective hydrosilylation of alkenes under mild conditions. Dalton Trans. 2025, 54, 7088–7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Bassler, G.C.; Morrill, T.C. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds, 4th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 249–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, J. Polymorphism in Molecular Crystals; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Llunell, M.; Casanova, D.; Girera, J.; Alemany, P.; Alvarez, S. SHAPE, Continuous Shape Measure Calculation, Version 2.0; Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Coxall, R.A.; Harris, S.G.; Henderson, D.K.; Parson, S.; Tasker, P.A.; Winpenny, R.E.P. Inter-ligand reactions: In situ formation of new polydentate ligands. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2000, 14, 2349–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, H.C.; Royal, D.S.; Helliwell, M.; Pope, S.J.A.; Ashton, L.; Goodacre, R.; Sharrad, C.A. Structural, spectroscopic and redox properties of uranyl complexes with a maleonitrile containing ligand. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 5939–5952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, K. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds, 4th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Signorini, O.; Dockal, E.R.; Castellano, G.; Oliva, G. Synthesis and Characterization of Aquo[N,N′-ethylenebis(3-ethoxysalicylideneaminato)]dioxouranium(VI). Polyhedron 1996, 15, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oher, H.; Pereira Gomez, A.S.; Wilson, R.E.; Schnaars, D.D.; Vallet, V. How Does Bending the Uranyl Unit Influence its Spectroscopy and Luminescence? Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 9273–9284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, M.A.; Dorfer, W.L.; Cary, S.K.; Cross, J.N.; Lin, J.; Schelter, E.J.; Albrecht-Schmitt, T.E. Why is Uranyl Formohydroxamate Red? Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 5280–5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, K.P.; Kalaj, M.; Kerridge, A.; Ridenour, J.A.; Cahill, C.L. How to Bend the Uranyl Cation via Crystal Engineering. Inorg. Chem 2018, 57, 2714–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, C.K.; Reisfeld, R. The uranyl ion, fluorescent and fluorine-like: A review. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1983, 130, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelani, P.O.; Burns, P.C. One-dimensional Uranyl-2,2′-bipyridine Coordination Polymer with Cation-Cation Interactions: (UO2)2(2,2′-bpy)(CH3CO2)(O)(OH). Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 11177–11183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.F.; Hayashibara, L.; Spadoro, J. Fluorescence properties of uranyl nitrates. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 1999, 60, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, W.J. The use of conductivity measurements in organic solvents for the characterization of coordination compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1971, 7, 81–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, G.R.; Miller, A.J.M.; Sherden, N.H.; Gottlieb, H.E.; Nudelman, A.; Stoltz, B.M.; Bercaw, J.E.; Goldberg, K.I. NMR Chemical Shifts of Trace Impurities: Common Laboratory Solvents, Organics, and Gases in Deuterated Solvents Relevant to the Organometallic Chemist. Organometallics 2010, 29, 2176–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takao, K.; Ikeda, Y. Structural Characterization and Reactivity of UO2(salophen)L and [UO2(salophen)]2: Dimerization of UO2(salophen) Fragments in Noncoordinating Solvents (salophen = N,N′-disalicylidene-o-phenylenediamine, L = N,N-Dimethylformamide, Dimethyl Sulfoxide). Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 1550–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | H2L (Polymorph B) | [UO2(L)(MeOH)] (1) | [UO2(L)(DMF)]·DMF (2·DMF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formula | C28H24N2O2 | C29H25N2UO5 | C31H36N4UO5 |

| Formula weight | 420.49 | 720.55 | 834.70 |

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | Pbca | C2/c | P21/c |

| a [Å] | 13.3437(5) | 26.8474(10) | 7.8653(4) |

| b [Å] | 15.2001(6) | 9.7734(4) | 19.8083(9) |

| c [Å] | 22.5397(9) | 20.3699(8) | 20.9529(9) |

| α [°] | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β [°] | 90.00 | 101.989(1) | 99.413(2) |

| γ [°] | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| V [Å3] | 4571.6(3) | 5228.3(4) | 3220.5(3) |

| Ζ | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| Τ [°C] | −113 | −93 | −113 |

| Radiation [Å] | Mo Kα (0.71073) | Mo Kα (0.71073) | Mo Kα (0.71073) |

| ρcalc. [g cm−3] | 1.222 | 1.831 | 1.722 |

| μ [mm−1] | 0.08 | 6.25 | 5.09 |

| F(000) | 1776 | 2768 | 1632 |

| θrange [°] | 3.0–27.5 | 3.1–27.5 | 3.0–27.0 |

| Measured, independent, and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 48,245, 4983, 3267 | 5701, 5701, 5200 | 70,963, 7008, 6481 |

| Rint | 0.057 | 0.062 | 0.028 |

| R1 [I > 2σ(I)] a | 0.0394 | 0.0517 | 0.0172 |

| wR2 [I > 2σ(I)] b | 0.1049 | 0.1365 | 0.0392 |

| Parameters | 385 | 340 | 550 |

| GoF on F2 | 1.04 | 1.11 | 1.08 |

| Largest differences peak and hole (e Å−3] | 0.13/−0.14 | 3.15/−1.56 | 0.53/−0.34 |

| Bond | 1 | 2·DMF |

|---|---|---|

| U1-O1 | 1.794(7) | 1.786(2) |

| U1-O2 | 1.770(7) | 1.782(2) |

| U1-O3 | 2.225(7) | 2.240(2) |

| U1-O4 | 2.307(7) | 2.255(2) |

| U1-O1M(MeOH)/O5(DMF) | 2.443(7) | 2.415(2) |

| U1-N1 | 2.588(8) | 2.528(2) |

| U1-N2 | 2.559(8) | 2.618(2) |

| C14-N1 | 1.470(13) | 1.471(3) |

| C15-N2 | 1.469(12) | 1.486(3) |

| C7-N1 | 1.289(12) | 1.294(3) |

| C22-N2 | 1.297(12) | 1.294(3) |

| C1-O3 | 1.356(13) | 1.312(3) |

| C16-O4 | 1.349(12) | 1.316(3) |

| Bond Angle | 1 | 2·DMF |

|---|---|---|

| O1-U1-O2 | 178.5(3) | 177.9(1) |

| O1-U1-O3 | 90.8(3) | 90.1(1) |

| O1-U1-O4 | 91.2(3) | 85.9(1) |

| O1-U1-O1M(MeOH)/O5(DMF) | 85.0(3) | 93.6(1) |

| O1-U1-N1 | 94.4(3) | 87.0(1) |

| O1-U1-N2 | 81.8(3) | 96.1(1) |

| O2-U1-O3 | 90.6(3) | 91.2(1) |

| O2-U1-O4 | 87.5(3) | 93.6(1) |

| O2-U1-O1M(MeOH)/O5(DMF) | 95.4(3) | 88.3(1) |

| O2-U1-N1 | 86.0(3) | 91.8(1) |

| O2-U1-N2 | 97.1(3) | 81.8(1) |

| O3-U1-O4 | 156.8(2) | 156.7(1) |

| O3-U1-O1M(MeOH)/O5(DMF) | 81.1(3) | 79.1(1) |

| O3-U1-N1 | 69.1(3) | 68.8(1) |

| O3-U1-N2 | 135.1(3) | 133.1(1) |

| O4-U1-O1M(MeOH)/O5(DMF) | 76.0(2) | 78.2(1) |

| O4-U1-N1 | 133.7(3) | 133.7(1) |

| O4-U1-N2 | 68.0(2) | 70.3(1) |

| O1M(MeOH)O5(DMF)-U1-N1 | 150.2(3) | 147.9(1) |

| O1M(MeOH)O5(DMF)-U1-N2 | 141.2(3) | 144.2(1) |

| N1-U1-N2 | 67.5(3) | 65.2(1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skiadas, S.G.; Papageorgiou, I.T.; Lada, Z.G.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Bekiari, V.; Psycharis, V.; Tsantis, S.T.; Perlepes, S.P. Reactions of the Uranyl Ion and a Bulky Tetradentate, “Salen-Type” Schiff Base: Synthesis and Study of Two Mononuclear Complexes. Crystals 2025, 15, 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110974

Skiadas SG, Papageorgiou IT, Lada ZG, Raptopoulou CP, Bekiari V, Psycharis V, Tsantis ST, Perlepes SP. Reactions of the Uranyl Ion and a Bulky Tetradentate, “Salen-Type” Schiff Base: Synthesis and Study of Two Mononuclear Complexes. Crystals. 2025; 15(11):974. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110974

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkiadas, Sotiris G., Ioanna Th. Papageorgiou, Zoi G. Lada, Catherine P. Raptopoulou, Vlasoula Bekiari, Vassilis Psycharis, Sokratis T. Tsantis, and Spyros P. Perlepes. 2025. "Reactions of the Uranyl Ion and a Bulky Tetradentate, “Salen-Type” Schiff Base: Synthesis and Study of Two Mononuclear Complexes" Crystals 15, no. 11: 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110974

APA StyleSkiadas, S. G., Papageorgiou, I. T., Lada, Z. G., Raptopoulou, C. P., Bekiari, V., Psycharis, V., Tsantis, S. T., & Perlepes, S. P. (2025). Reactions of the Uranyl Ion and a Bulky Tetradentate, “Salen-Type” Schiff Base: Synthesis and Study of Two Mononuclear Complexes. Crystals, 15(11), 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110974