Abstract

The manufacturing techniques, structural features, and optical attributes of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles are highlighted in this study. These nanoparticles are notable for their remarkable photocatalytic activity, cheap cost, chemical stability, and biocompatibility. TiO2 consists of three polymorph structures: anatase, rutile, and brookite. Because of its electrical characteristics and large surface area, anatase is the most efficient for photocatalysis when exposed to UV light. The crystallinity, size, and shape of titania nanoparticles (NPs) are influenced by diverse production techniques. Sol-gel, hydrothermal, solvothermal, microwave-assisted, and green synthesis with plant extracts are examples of common methods. Different degrees of control over morphology and surface properties are possible with each approach, and these factors ultimately affect functioning. For example, microwave synthesis provides quick reaction rates, whereas sol-gel enables the creation of homogeneous nanoparticles. XRD and SEM structural investigations validate nanostructures with crystallite sizes between 15 and 70 nm. Particle size, synthesis technique, and annealing temperature all affect optical characteristics such as bandgap (3.0–3.3 eV), fluorescence emission, and UV-visible absorbance. Generally speaking, anatase has a smaller crystallite size and a greater bandgap than rutile. TiO2 nanoparticles are used in gas sensing, food packaging, biomedical coatings, dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs), photocatalysis for wastewater treatment, and agriculture. Researchers are actively exploring methods like adding metals or non-metals, making new composite materials, and changing the surface to improve how well they absorb visible light.

1. Introduction

In the last ten years, nanotechnology has emerged as one of the most significant topics and changes in the technology of the 21st century; as a result, several modern applications of nanotechnology have expanded exponentially around the world in various fields. By reducing the size of the particles from micrometers to nanometers, practically the physical properties of materials are modified. These changes are due to the expanding surface-to-volume proportion and the alterations in the dimensions of the transferring item inside the areas influenced by quantum phenomena. Furthermore, the distribution of internal surface atoms alters, and the properties of the surface atoms govern the behavior of the interior atoms. The properties and interactions of the particles are altered by these modifications. Boosting the surface area is a critical determinant in the efficacy of catalysts. Furthermore, increasing the nanoparticles’ surface (shell surface) may have a significant effect on how materials interact, including nanocomposites, and alter some of their mechanical, electrical, and chemical characteristics [1]. A comparison between the two effects that occurred in materials reduced from microscale to nanoscale is presented in Table 1 [2]:

Table 1.

Comparison between the two effects that occurred in materials reduced from microscale to nanoscale.

Nanomaterial particles with a diameter of 1 to 100 nm have found extensive application due to their distinct physicochemical characteristics. Due to exceptional textural and structural properties, nanostructured materials have been of enormous application as catalysts. Important metal oxides, including TiO2, SnO2, VO2, and ZnO, have been the focus of much effort. Titanium is a well-known and extensively researched material due to its optical, physical, electrical, biocompatible, and stable chemical structure. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is one of the most efficient raw materials and finds usage in a wide range of fields, including photocatalysis, medicine, the environment, sensors, paintings, solar energy, and much more. This material is inexpensive, has outstanding thermal and chemical stability, and is extraordinarily resistant to corrosion [7].

Titania is also used as a food additive in the pharmaceutical sector [8]. Other medical uses of this material include the eradication of viruses and bacteria and the deactivation of cancerous cells, including the elimination of oil leaks [9]. TiO2 Nanoparticles (NPs) are utilized for the removal of emerging pollutants [10]. Furthermore, TiO2 NPs are frequently used as photo-anode materials due to their efficient light absorption, particularly in the UV region [11,12]. TiO2 has a suitable energy band gap of less than 3.5 eV, which permits the use of it as a photocatalyst material [13]. The current developments in TiO2 nanostructures and their environmental, photocatalytic activity, splitting water, gas sensors, and energy applications have been summarized [14].

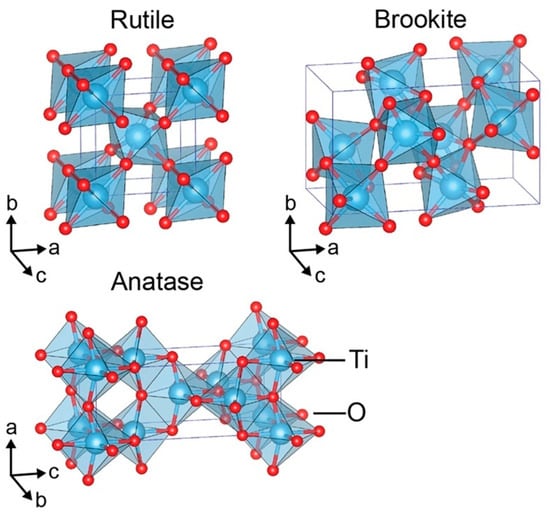

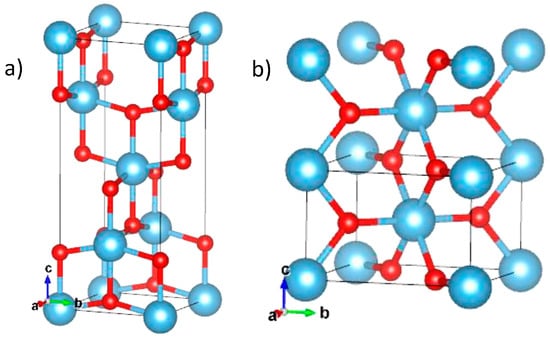

As can be depicted in Figure 1, three crystalline forms of TiO2 have been identified: anatase, rutile, and brookite are disentangled [15]. Under UV irradiation, anatase-type TiO2 is typically employed as a photocatalyst due to its crystalline structure (tetragonal system with dipyramidal habit). Similarly, the tetragonal crystal structure of rutile-type TiO2 (with prismatic habit). In brookite-type TiO2, the crystalline structure is orthorhombic. TiO2’s remarkable photocatalytic activity makes it the favored material in the anatase phase, as well as its superior specific area, additional negative conduction band edge potential, non-toxicity, photochemical stability, and affordability [2]. Water and air are decontaminated and fumigated using anatase-TiO2 material as a photocatalytic material [16].

Figure 1.

Illustration of different-crystal-forms-of-TiO2 [15].

TiO2 morphologies present nanostructures in different types, like nanotubes [17], nanowires [17], nanorods [18], and mesoporous structures [19]. TiO2 nanostructures have been created using a broad range of synthesis techniques in recent years, including hydrothermal, sol-gel [14], solvothermal [20], direct oxidation, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), electrodeposition [21], microwave, and sonochemical methods [22].

2. Preparation Methods of Titanium Dioxide

Nanomaterials of TiO2 were elaborated by three main procedures: chemical, physical, and biological techniques. Reducing agents like sodium citrate or sodium borohydride were used in the chemical processes; however, laser irradiation, electrolysis, and thermal decomposition were employed in the preparation of TiO2 by physical methods. Due to the high cost of employing complex systems like vacuum in physical procedures, chemical techniques are widely used in the preparation of nanomaterials [23]. During the synthesis, different characteristics like the shape and size of TiO2 and also more properties may be controlled in general [24]. The environmental impact of the hazardous chemicals produced during the chemical and physical processes limits the employing of these two techniques [24,25]. Several authors utilize the biological technique (green synthesis) as an eco-friendly and less hazardous alternative. Ultimately, the reaction stabilizeds and lowers the agent characteristics of the plant extract [25].

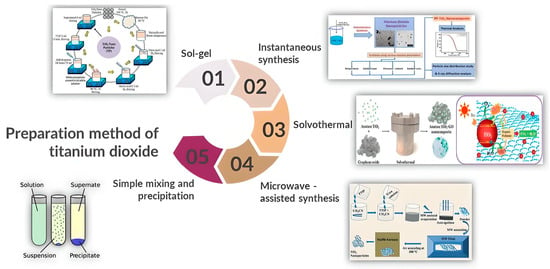

Numerous techniques, including the sol-gel technique, solvothermal method, simple mixing, instantaneous synthesis method, microwave-assisted synthesis method, and precipitation method, were used to elaborate the manufacture of TiO2 nanoparticles, according to various works. Figure 2 depicts a schematic of these popular synthesis techniques for making TiO2 [23].

Figure 2.

Illustration of the preparation-methods of titanium dioxide [23]. Reproduced from [Reference: Z.I. Tarmizi et al., IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci., 2022, [1091/012064], with permission from IOP Publishing.

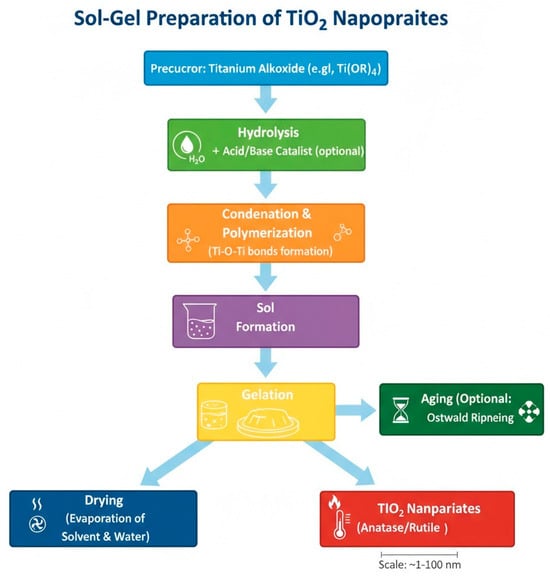

2.1. Sol-Gel Method

Because of numerous advantages, the sol-gel procedure is widely recognized as the most familiar approach used for the creation of TiO2 NPs [26], such as complete control over surface and bulk properties [27]. It is capable of producing nanoparticles with a variety of shapes. For example, tubes, sheets, rods, wires, particles, and aerogels [28]. Using this technique, promising characteristics such as particle morphology, specific grain size, porosity, and compositional homogeneity were obtained for produced titanium dioxide nanoparticles [29]. Another advantage of using the sol-gel synthesis process is that preparation of the gel proceeds in 4 h [30], at a temperature frequently around 80 °C [31].

This technique produced nanocomposites and nanoparticles in reduced circumstances by mixing two or more different phases to create hybrids [32]. Also, this process makes it simple to create homogeneous, reasonably priced nanomaterials with complex compositions [33]. This procedure is characterized by a chemical change that turns sol into a gel phase and then a solid oxide substance [34], passing by three main steps: freeze-drying and calcination [35]. The wet chemical technique (sol-gel) is normally used to produce nanoparticles of TiO2 for material sciences and ceramic engineering applications [23]. Heshmapour and his co-researcher prepared TiO2 NPs using a sol-gel process in combination with ceramic and PANI (Polyaniline) to reduce the agglomeration effect. As a result, agglomeration discontinuity and smaller particles were noticed after the combination of ceramic and PANI. Ceramics’ porous surface increases the quantity of catalytic active sites, which helps mitigate agglomeration. As a result, TiO2’s enhanced photocatalytic activity was noted following the combination of PANI with ceramics [36]. Moreover, to enhance TiO2 nanomaterials, other nanocomposites like hyperbranched polyethyleneimine polymer template (HPEI) and waste-produced polymeric biosurfactant were employed in the sol-gel process [23].

It has been found that highly pure crystalline fine particles can be obtained at low temperatures without washing actions [23,34]. Figure 3 represents a schematic diagram for the preparation method of TiO2 by sol-gel method.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the preparation methods of titanium dioxide by sol-gel method.

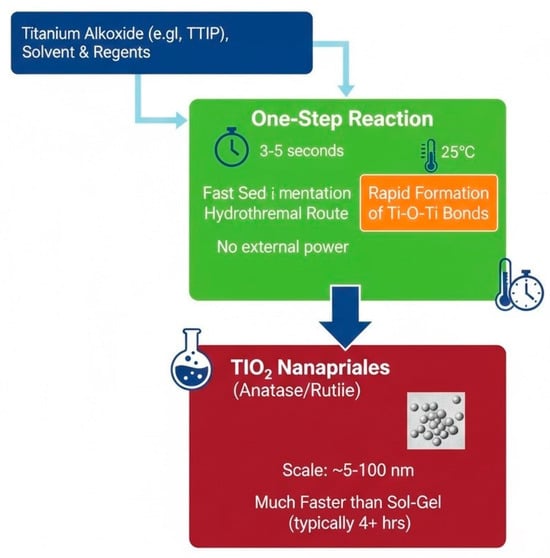

2.2. Instantaneous Synthesis Method

The instantaneous synthesis method, presented in Figure 4, uses fast sedimentation or hydrothermal routes to produce nanoscale TiO2 NPs in a brief time. The capability to supervise particle size morphology, simplicity, and speed makes this method useful for synthesizing this type of nanocomposites [23]. The preparation of TiO2 is carried out in one step only, as the name of this method suggests [37]. With no extra power from outside sources, the reaction time of around three to five seconds was achieved at 25 °C. Production of TiO2 by Prakash and his co-researcher was achieved by using polypropylene in a short time, only about 5 s, at 25 °C [37]. This process is shown to be quicker than the sol-gel approach, which typically requires stirring the liquid for at least four hours before drying it out at room temperature to produce TiO2 NPs [38].

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram illustration the rapid, one-step instantaneous synthesis route for TiO2 nanoparticles.

2.3. Solvothermal Method

For the one-step production of pure anatase-TiO2 NPs, the solvothermal approach is regarded as an unusual route. In this technique, precipitation of arbitrary phases from the liquid phase was directed [39] and it was considered an attractive approach to create nanoparticles with different morphologies [40]. The solvothermal method’s name comes from the utilization of organics during the synthesis process. TiO2 NPs photocatalytic activity produced by the solvothermal approach was enhanced by a post-synthesis treatment that used a quick cooling procedure, “quenching” [41].

Some organic solvents are frequently employed in solvothermal methods, such as methanol [42], 1,4-butanediol [20], toluene [43], and amines [20]. An overview of the physical and chemical properties is given in Table 2 [44].

Table 2.

Properties of commonly used hydrothermal/solvothermal Solvents.

In the solvothermal procedure, the reactions happen at relatively low pressures and temperatures, and another important point to remark on is that solvothermal techniques can lead to precursors that are susceptible to water [49]. Furthermore, the simple achievement of crystal phase control, morphology, and free foreign anions in the synthesized materials in the solvothermal process [50].

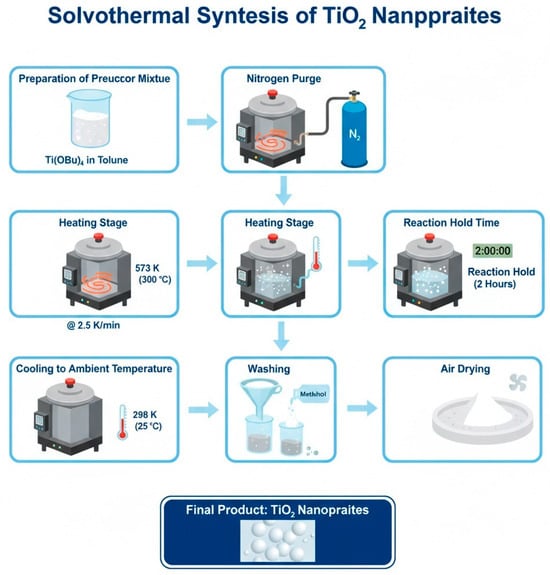

The starting material used is titanium (IV) n-butoxide, Ti(OBu)4 (97%). An autoclave of 300 mL was charged by a mixture of 25 g of Ti(OBu)4 suspended in 100 mL of toluene. Following the autoclave’s full nitrogen purge, the product was heated to 573 K at a rate of 2.5 K/min, maintained there for two hours, and then allowed to cool to ambient temperature. The result was repeatedly rinsed with methanol before being allowed to dry in the air [2]. Figure 5 represents the steps for the preparation of TiO2 by solvothermal method.

Figure 5.

Illustration of the preparation TiO2 by solvothermal method.

2.4. Hydrothermal Method

For applications in the ceramics industry, the hydrothermal process is frequently used to create exceptionally homogenous and monodispersed nanoparticles as well as nano-hybrid and nanocomposite structures [51]. This technique requires water as a catalyst and sometimes as a constituent of solid phases at high pressure and temperature in the range of (P < 100 bars, T ≤ 200 °C) [52].

This method usually employs an autoclave where the reaction occurs in aqueous solutions at a controlled temperature or pressure. The attraction of this method is the possibility to prepare highly homogeneous mono-dispersed nanoparticles and nano-hybrid and nanocomposite compounds [53] generally employed in applications within ceramics production [54]. Numerous investigations detailed the mild hydrothermal preparation of TiO2 NPs by examining a variety of factors, including temperature, experimental length, pH, solvent type, % fill, and the preliminary charge on the final product [55]. Another important use of this technique is to produce nanofibers and nanotubes of TiO2 [56].

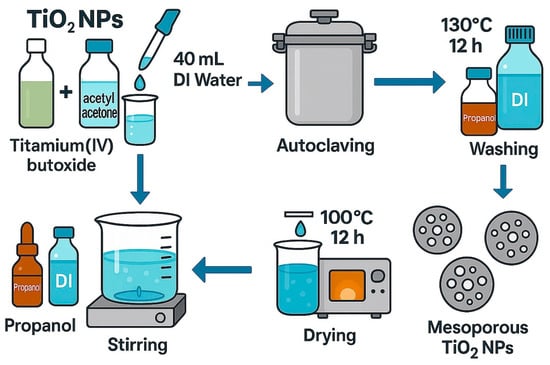

Employing this method, we obtain TiO2 NPs by applying equal moles of butoxide of titanium (IV) together with acetylacetone to decrease the condensation and hydrolysis processes. Subsequently, 40 mL of distilled water (DI) was added to the mixture and stirred for about 5 min at room temperature. After that, the mixture was processed in a stainless steel autoclave for 12 h at 130 °C. After that, the autoclave was let to cool to room temperature. Both propanol and DI were used frequently to clean the finished product to eliminate the remaining chemicals in the product, and then it was dried at 100 °C for 12 h. The final products of this technique are TiO2 NPs with a mesoporous structure, measuring 3–4 nm in diameter, with a high level of photocatalytic activity [57]. The process for the preparation of Titania is illustrated in the Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the preparation TiO2 by hydrothermal method.

2.5. Microwave-Assisted Method

One approach for creating TiO2 NPs is microwave-assisted synthesis, which has grown in popularity because of its superiority over conventional heating processes [58]. In this procedure, the microwave instantly heats the reactants. As electromagnetic radiation happens at a moderately minimal value, the result is the chemical reaction is much faster [59]. Additionally, microwave irradiation is instantly localized, producing superheating where energy is transferred. The duration is about 10−9 s for every electromagnetic energy cycle because of the dipole rotation. Hence, faster reaction in less time occurs due to the molecules’ movement [60].

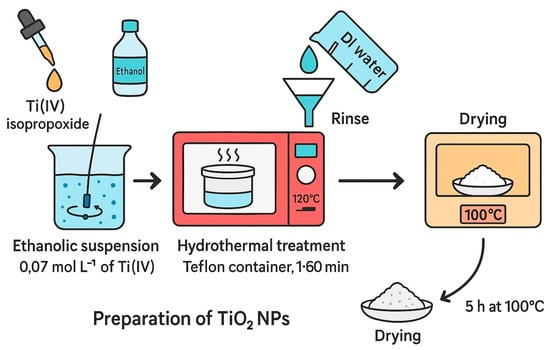

The procedure for preparation of TiO2 NPs consists of making a solution by mixing Ti(IV) isopropoxide (Aldrich, 97%) and ethanol (Vetec, 99.8%) to form an ethanolic suspension with the concentration of 0.07 mol L−1 of Ti(IV) with constant mixing. The resultant product was placed inside a Teflon container and heated by microwave radiation for varying periods of time—1, 5, 15, 30, and 60 min—at 120 °C and pressures of around 200 kPa. Once the reaction was completed, the resulting product (white powder) was rinsed with DI various times and then dried up for 5 h at 100 °C [61]. Illustration of the preparation TiO2 by microwave-assisted method is depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Illustration of the preparation TiO2 by microwave-assisted method.

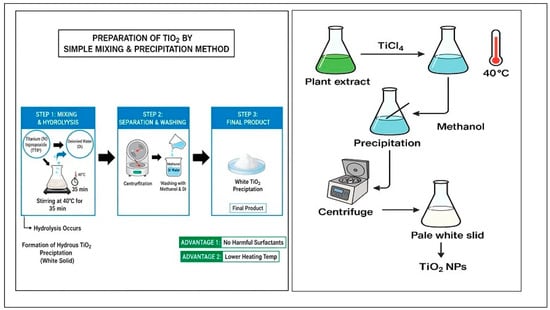

2.6. Simple Mixing and Precipitation Method

This method is a common and convenient procedure that can be used to obtain TiO2 NPs. The simple mixing technique represented in Figure 8, depends on the formation of supersaturated solution “precipitation” by changing the solution into solid materials [62]. Moreover, this method is characterized by simplicity in preparation without complex conditions. Also, another attraction is the simple control of the particle size and form [62]. An extract from plants was used in some research to create TiO2 NPs [23]. In order to prepare TiO2 NPs, the plant extract was mixed with TiCl4 under constant stirring till the transparent color converted into pale white, which indicates the completion of the process [63].

Figure 8.

Schematic diagrams for preparation of TiO2 by simple mixing and precipitation method.

Another method employed by another team was without plant extract, where a mixture of both titanium(IV) isopropoxide and DI was stirred at 40 °C for 35 min. While the mixture was stirred, the process suffered hydrolysis, and precipitation of hydrous TiO2 was produced. The precipitation was centrifuged and cleaned up with methanol and DI; thus, we obtained the final product, white precipitation of TiO2 [64]. So, using this method has an extra advantage by using no harmful surfactants and heating the precipitation at a lower temperature [18].

3. Structural Properties of TiO2 Nanomaterials

Physical properties of Titanium oxide are listed in Table 3 [32,65,66]. TiO2 has three distinct crystallographic forms: rutile, brookite, and anatase. Rutile and anatase surfaces are particularly explored, while at very low temperatures brookite phase converts into the rutile form. The most thermodynamically stable phase is rutile, with the smallest surface energy found on the (110) face, and it is highly studied in the literature [67]. Rutile and anatase unit cell structures of the TiO2 nanomaterials are illustrated in Figure 9 [68]. Both configurations can be explained with sequences of TiO6 octahedra, where an octahedron of six O2− ions surrounded each Ti4+ ion. The difference between the two crystal structures is the representative pattern of the octahedra sequences and the deformation of each octahedron. Because of the significant octahedron distortion, anatase symmetry is lower than orthorhombic, but a small orthorhombic distortion was seen in the octahedron rutile phase. Compared to rutile, the anatase Ti–O distances are shorter and the Ti–Ti distances are longer in the anatase phase.

Table 3.

Physical properties of Titanium oxide (TiO2).

Figure 9.

Illustration of unit cells of anatase TiO2 (a) and rutile TiO2 (b). Large light-blue and small red spheres are Ti4+ and O2− ions, respectively [68].

Ten neighboring octahedrons (eight sharing corner oxygen atoms and two sharing edge oxygen pairs) encircle each octahedron for rutile structure, whereas all octahedrons are surrounded by eight neighbors (four sharing a corner and four sharing an edge) in the form of anatase phase.

The two forms of TiO2 are different in electronic band configurations and mass densities because of the lattice structure differences. The instability of anatase with pressure depends on the dimension of the nanomaterials, whereas some researchers indicate for minor crystallites the structure is sustained under higher pressures [69].

For anatase’s pressure-induced phase shift at room temperature, there are three regimes established corresponding to the size: medium crystallite sizes, and in the case of the lowest crystallite proportions, an anatase-amorphous transition regime. A transition regime between anatase and baddeleyite developed, while for big nanocrystals towards macroscopic single crystals, the anatase-α-PbO2 transition regime was revealed [70].

Several theoretical investigations were conducted on the phase durability of TiO2 NPs. Applying a thermodynamic model under different environments [69,71]. They confirmed the crucial impact on phase stability and the geomorphology of nanocrystals by surface passivation. Surface hydrogenation revealed major changes in the rutile nanocrystals’ form; instead, in the anatase phase, this change does not occur. For spherical particles, the crossover point was around 2.6 nm.

For anatase nanocrystals, a phase transition was seen at a diameter of 9.3–9.4 nm for a smooth and faceted surface at low temperatures. Once the surface connecting oxygens was H-terminated, the transition size slightly decreased to 8.9 nm, while the size augmented pointedly to 23.1 nm when equally the under-coordinated titanium atoms and associating oxygens of the trilayered surface were H-terminated. Below the cross point, it is seen that the anatase phase was more stable than the rutile phase [72]. For TiO2 NPs studies in vacuum or water conditions, the vacuum phase transition magnitude (9.6 nm) is found to be smaller than the water phase transition size (15.1 nm) [73].

They discovered that the thermo-chemical effects can vary for various faceted or spherical NPs depending on their size, shape, and level of surface passivation when predicting the transition enthalpy of anatase and rutile nanocrystalline phases [74].

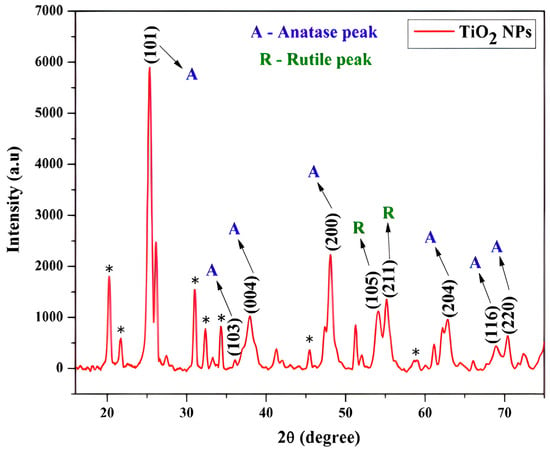

Figure 10 displays the rutile TiO2 and anatase particle X-ray diffraction patterns, the X-ray source used is Cu radiation (λ = 1.540 Å). Nanoparticle samples were obtained by sol-gel technique with heat processes at 450 °C and 750 °C, respectively. The XRD patterning in Figure 10(A) displays the reflections that correspond to the anatase phase (JCPDS: 21-1272) [75].

Figure 10.

Illustration of XRD analysis of TiO2 nanoparticles (Anatase, Rutile peaks and unidentified crystalline phases marked with an asterisk may be present due to a crystalline impurity phase) [75].

This indicates that around 450 °C, the anatase phase produced the amorphous TiO2. Other investigators reported that the conversion of the anatase to the rutile phase in the annealing route does not happen at temperatures lower than 600 °C [38]. The proportional intensity of the anatase concerning rutile peaks disappeared after the annealing process concluded at 750 °C (refer to Figure 10). As a result, nearly only the rutile phase’s peaks were visible, which at this temperature exhibits a complete phase modification from the anatase to the rutile phase. According to previous research, the generated TiO2 powder was found to be amorphous [76]. Every peak in Figure 10(R) was classified as a rutile phase tetragonal structure, with corner-bonded (TiO6) octahedra establishing the crystal structure (JCPDS:21-1276). But anatase peaks were broader in contrast with the intensity of rutile peaks appearing as sharp peaks in the XRD pattern. In Figure 10 some unidentified crystalline phases marked with an asterisk, not attributable to TiO2, may be present due to a crystalline impurity phase.

By using Scherrer’s calculation, the full width at half maximum peak (FWHM) of the (h k l) and 2θ have been employed to determine the crystallite dimensions [32]

The typical crystallite size is represented by D in Å, with K denoting the shape factor (0.9). The wavelength of the X-ray used is λ, specifically 1.5406 Å for CuKα radiation. Bragg’s angle is indicated by θ, while β refers to the adjusted line broadening of the NPs.

From Scherrer’s formulas calculation, the typical crystallite sizes were estimated to be 15.31 nm for the anatase phase and 70.96 nm for the rutile phase. Where excessive annealing temperature increased the TiO2 crystallite size. Lattice constants ‘a’ and ‘c’ for the tetragonal configuration (where a = b ≠ c, and α = β = γ = 90.0°) can be determined using the following formula [77]:

where h, k, and l stand for the peak’s Miller indices. The volume of the unit cell (V = a2c) may be computed using the values of “a” and “c”. So, XRD patterns demonstrate a strong level of agreement with the standard JCPDS of rutile (21-1276) and anatase (21-1272) TiO2. We use the following equations to estimate the structural parameters [78]:

Structural parameters such as dislocation density, crystallite size, stacking fault, texture coefficient (TC), and microstrain of rutile and anatase TiO2 NPs are presented in previous work [78]. The decreasing tendency for lattice defects such as stacking fault (SF), micro strain (ε), and dislocation density (δ), while the temperature rises from 450 to 750 °C, which may be due to the great orientation along the (110) direction and enhancement of crystallinity. The straightforward carrier mobility in the lattice was attributable to the lowest values of micro strain (ε) and dislocation density (δ) [79]. It was commonly noticed that decreasing values of ε and δ in the TiO2 NPs are caused by the well-known process of crystallite size growth [80]. The texture of a specific plane is represented by the texture coefficient (TC). From TC(hkl), numerical data on the preferred crystallite orientation was obtained. Where I(hkl) is the computed qualified intensity of a plane (hkl) acquired from the JCPDS data, and I0 (hkl) is the plane’s standard intensity. TC reveals that the anatase phase is extremely oriented in (101) and the rutile phase is particularly oriented in the (110) direction.

The primary particle (single TiO2 unit) creation occurs because of the agglomeration effect, where the agglomeration number indicates how many primary molecules or particles make up a precise NP of a specific size [38].

4. Optical Properties of TiO2 Nanomaterials

The prepared titania in both phases, rutile, and anatase, have a large refractive index of about 2.7 and 2.5, respectively [81,82]. These values of refractive index are used to evaluate the metal oxide’s capability to disperse photons. Rutile is considered an ideal pigment because it has a higher efficiency of light reflection than brookite and anatase [83]. The interesting duality of light behavior for the metal oxide by absorbing and scattering ultraviolet radiation makes it a very interesting candidate for photocatalysis application [84].

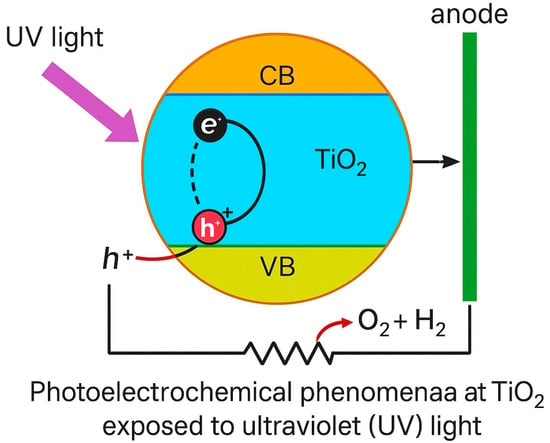

Metal oxide is an impressive semiconductor under ultraviolet (UV) light, and due to its photoelectric properties, it is capable of catalyzing redox reactions [85,86]. This corresponds to Titania’s band configuration as represented in Figure 11 [87]. The area between the valence band, where valence electrons occupy the conduction band at lower energy levels, and where additional electrons are replenished at higher energy levels is known as the energy gap (EG) [88]. There are no energy levels to accommodate electrons on the inside of a band gap [89]. EG is also equivalent to or lesser than ultraviolet photon energy [89].

Figure 11.

Illustration of photoelectrochemical phenomena at TiO2 exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light.

For greater EG values, the region can be related to an obstacle for electron transmission; in the valence band, intense UV light should be absorbed by electrons to guarantee their excitement to energy levels inside the conduction band [89,90]. Titania energy gap (EG) reveals anatase values of 3.3 eV, rutile values of 3.1 eV, and brookite values of 3.1–3.4 eV [90,91,92].

Lighting up TiO2 with UV light, electrons in the fundamental state (valence band) create positive holes in the valence band (h+ VB) by moving to the excited state (conduction band) (e− CB). Subsequently, adsorbed molecules upon the catalyst’s surface, such as oxygen and water, can suffer redox reactions. Reduction occurs at the conduction band, with the help of higher photoelectrons, e− CB; however, oxidation happens at the valence band, within h+ VB electron acceptors [93,94].

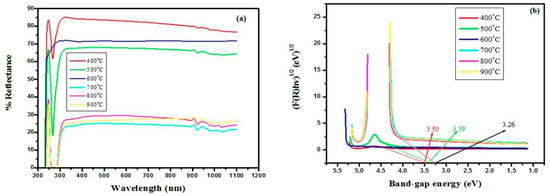

Reflectance spectra of annealed NP at various temperatures are displayed in Figure 12a in the 200–1100 nm range [95]. For NPs treated at 400 °C, the maximum reflectance of 85.26% was observed; however, the minimum reflectance of 23.38% corresponds to a 700 °C annealing temperature. By using the Kubelka–Munk formula Equation (7), the band gap energy (Eg) for TiO2 NPs was approximated [96] where the value ∞ indicates that the sample layer is thick enough to hide the support for which the required material is employed and deposited, and the Kubelka–Munk function is represented by (F(R)).

where (s) in (m−1) signifies the scattering coefficient and (k) in (m−1) is the absorption constant. The graph of (F(R)hv)1/2 with photon energy (hv), from which the band gap was computed, is displayed in Figure 12b utilizing Tauc equation Equation (8) [95].

where ∝ is the linear absorption factor and hv is the photon energy value, The separation gap amid the valence and conduction bands is denoted by Eg, and the constant γ is a constant on the likelihood of a transition; it accepts values like 2 for direct permitted transitions, 3 for direct banned transitions, and 1/2 for indirect allowed and 3/2 for indirect forbidden ones [97]. Substituting ∝ with Kubelka equation F(R∞) (Equation (7))

Figure 12.

Graph showing (a) reflectance spectra and (b) band gap plot for TiO2 prepared at different annealing temperatures [95].

In this study, the (γ) value of indirect transition = 1/2 was chosen for the optical analysis because of its high accuracy. When the quasi line is derived to zero absorption constant (∝≡ F(R∞)≡ 0), the x-intercept provides an estimated value of the band gap (Eg). Equation (9) almost relates to a linear equation y = mx + c. It was noticed that increasing crystal size delivers a lesser band gap value, thus the crystal size results in a reduced band gap as the annealing temperature increases [98]. Several articles have proven that the anatase phase has a larger optical band gap than the rutile shape, even if the predicted band gap fluctuates from 3.26 to 3.5 eV [99].

4.1. FTIR Analysis

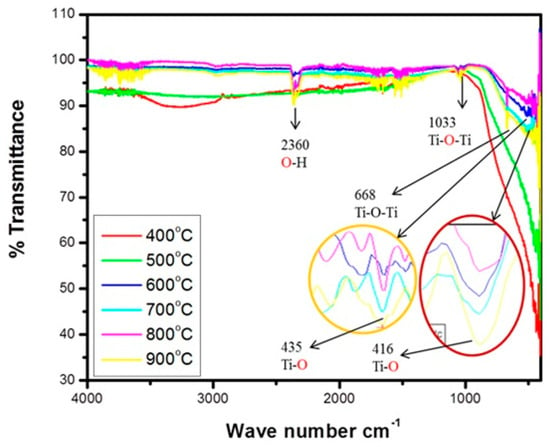

Examining the expanding and bending vibrations of the current functional bands in TiO2 nanoparticles using infrared spectroscopy realized in the range of 400–4000 cm−1 was represented in Figure 13 [95]. The primary bands at the fingerprint and functional group regions (1033, 2360, 416, 435, and 668 cm−1) are depicted by infrared spectroscopy. Ti-O-Ti expanding vibrations of TiO6 are responsible for the stated stretching vibrations at 668 and 1033 cm−1, which grew as the annealing temperature rose [95], whereas 416 cm−1 and 435 cm−1 were both associated with Ti-O vibration [95]. The 2360 cm−1 stretching seen in the efficient group band was attributed to the stretched vibration of the Ti-OH absorption band that contains –OH [95]. FTIR spectra in both anatase and rutile structures affirm the existence of vital functional groups Ti-O and Ti-O-Ti of TiO2 nanoparticles that are associated with bending from the tetrahedral structure. Ti-OH stretching was formed from the coupling of the –OH at the 2360 cm−1 peak using ethanol diethanolamine as the solvent, precursor, and titania orthotitanate. The angular vibrations observed between 400–500 cm−1, 1300–2100 cm−1, and 3450–4000 cm−1 challenge Diethanolamine (DEA) is the source of many peaks that are more difficult to identify, such as the bending and stretching vibrations of -CH2 and -NH, which exist but have less distinct bands. For -CH2 and -NH, the stretching vibration is found between 2800 and 3000 cm−1 and 300 and 3500 cm−1, respectively [95]. A broader band between 400 and 1000 cm−1 was observed and is advocated for the Ti-O and Ti-O-Ti bridging stretching modes [95]. Thus, Ti-O-OC bonding is observed around the 1100 cm−1 peak [95]. Wave number 1627 cm−1 has a similar relationship to a peak associated with the efficient group of O-H vibration linked to the absorbed water [100]. The hydrogen bonding that is correlated with the oxygen-containing groupings is responsible for the 2342 cm−1 peak [101]. The last two peaks were linked to the water and surface-adsorbed hydroxyl groups that were physically and chemically adsorbed on the surface of the TiO2 particles. Nonetheless, the spectra show a decrease in the equivalent stretching vibration, which may be related to the gel glowing during the annealing process.

Figure 13.

FTIR spectra showing the effects of annealing temperature on the functional groups of TiO2 NPs [95].

4.2. Absorption

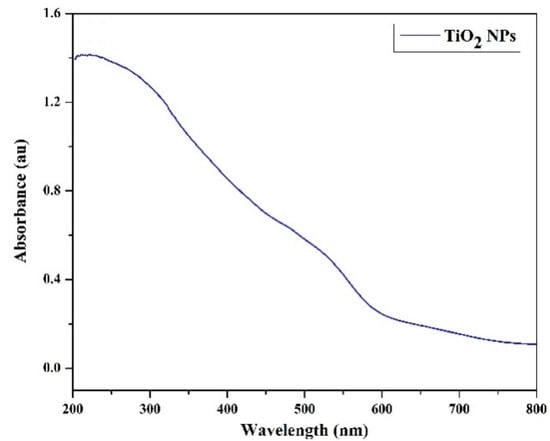

Using UV-visible spectra, the optical investigations of the produced nanoparticles were examined. The absorbance of the produced nanomaterials at room temperature in the nanoscale range is displayed in Figure 14 [75]. The UV spectra in the 200–1250 nm range were examined. Good absorbance in the UV zone is explained by the absorbance peak that appears at 323 nm.

Figure 14.

UV spectrum for TiO2 [75].

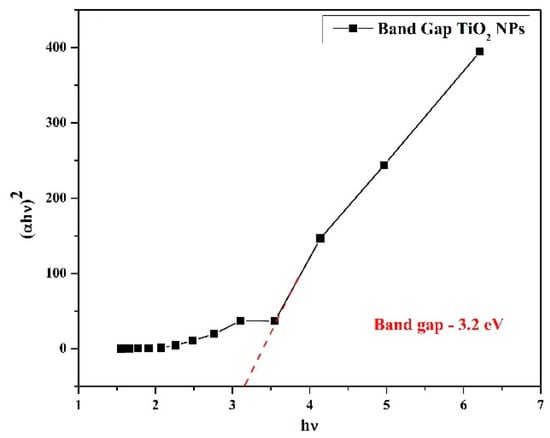

The energy bandgap (Eg) is measured from the basic absorption to determine its value. One way to express the relationship between α and hν explained in Equation (9). Accurate bandgap energy may be determined by plotting hv versus (αhν)2. The plot’s straight-line segment (hv versus (αhν)2 to α = 0) may be found using bandgap energy [102]. Using Figure 15 [103], the Eg value of TiO2 nanoparticles is 3.2 eV. Due to their high bandgap energy, TiO2 nanoparticles can be employed in other processes, such as photocatalysis [104].

Figure 15.

Band gap of TiO2 nanoparticles [75].

A particle size analyzer was utilized to estimate the particle size distribution of TiO2 NPs, where the average width of the particles was between 1 to 460 nm. Furthermore, the highest particle size value is 131 nm [105].

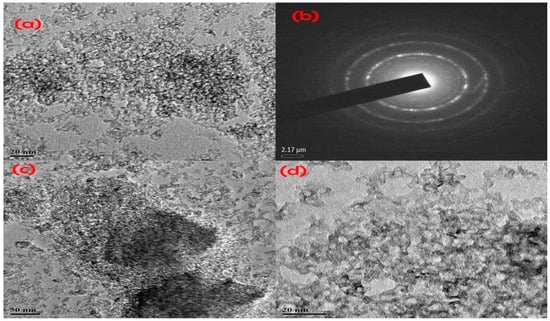

Figure 16 illustrates a typical TEM image of TiO2 NPs. Agglomerated nanoparticles with an exceptionally high surface area-to-volume ratio were found for a variety of environmental factors, including temperature, solvent, and local forces (physical, chemical, and Van der Waals, among others) [103].

Figure 16.

Illustration of (a,c,d) HRTEM image of TiO2 nanoparticles and (b) SAED pattern [103].

The crystallite nature, particle size, and shape are further explained by the use of a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM). In Figure 16, a HRTEM picture clearly shows that the obtained TiO2 nanoparticles have a crystalline, spherical shape and form were confirmed by [106]. HRTEM pictures (Figure 16a,c,d) show that the TiO2 nanoparticle was fairly small, at about 12 nm. The pictures in Figure 16c,d nearly match those in Figure 16a. According to the illustration, the spherical form of the TiO2 nanoparticles has been proven. The SAED (selected area electron diffraction) pattern of TiO2 nanoparticles is seen in HRTEM pictures (Figure 16b) [103].

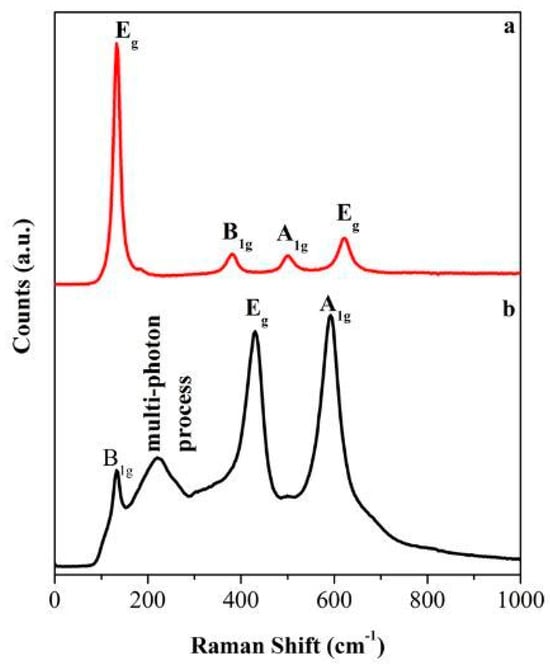

4.3. Raman Spectroscopy

One effective analytical method for describing materials at the molecular level is Raman spectroscopy, particularly effective for studying TiO2 (titanium dioxide) nanomaterials. This method uses the inelastic scattering of the monochromatic beam, frequently from a laser, to reveal details about a material’s vibrational modes, which can be correlated to its molecular structure, phase, and interactions. This technique is extensively used in the field of nanotechnology for TiO2 materials. It aids in understanding the interactions of TiO2 nanoparticles with biological systems, such as their effects on red blood cells, which is crucial for biomedical applications [107]. The method is also used to investigate TiO2’s surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) characteristics, which improve organic molecule identification [108]. Since Raman spectroscopy is regarded as a non-destructive method, materials may be analyzed without having their structural integrity changed. It requires little to no sample preparation, making it suitable for in situ studies. Also, the technique can detect low concentrations of materials, which is beneficial for studying doped or modified TiO2 NPs [109]. Despite its advantages, Raman spectroscopy has limitations, such as fluorescence interference from certain materials, which can obscure the Raman signals. Additionally, the technique may require complementary methods, such as FTIR (Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy), for comprehensive characterization. The distinctive Raman peaks of TiO2 phases allow for their identification. For instance, anatase shows prominent peaks at approximately 144 cm−1, 197 cm−1, 399 cm−1, and 640 cm−1, while rutile exhibits peaks at around 143 cm−1, 447 cm−1, and 612 cm−1 see Figure 17 [110]. Table 4 shows the characteristics of Raman peaks for anatase and rutile structures.

Figure 17.

Raman spectra of (a) anatase, and (b) rutile TiO2. [111]. [Swapna Challagulla, Kartick Tarafder, Ramakrishnan Ganesan, Sounak Roy, Structure sensitive photocatalytic reduction of nitroarenes over TiO2. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7, 8783].

Additionally, Raman spectroscopy may reveal information about the thickness and particle size of TiO2 nanopowder films. The broadening of Raman peaks can indicate smaller grain sizes, which are essential for solar energy conversion and photocatalysis applications [107,112]. Advanced techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) can be applied to Raman spectra to quantitatively analyze mixtures of TiO2 polymorphs. This allows for the determination of the relative proportions of anatase and rutile in a sample, which is important for improving their performance in numerous applications [107,113].

A summary of Raman spectroscopy characteristics for TiO2 nanomaterials is illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Raman Peaks for TiO2 Phases.

Table 4.

Raman Peaks for TiO2 Phases.

| TiO2 Phase | Characteristic Raman Peaks (cm−1) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Anatase | 144, 197, 399, 640 | [114] |

| Rutile | 143, 447, 612 | [114] |

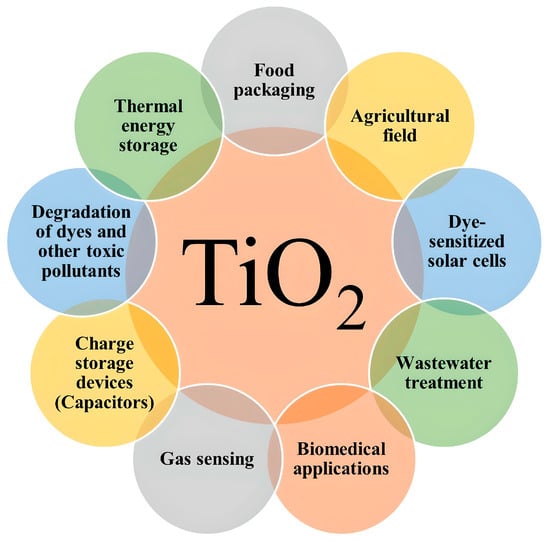

5. Applications of Titania

Because of its optical, electrical, and superior catalytic characteristics, titania is considered an exquisite nanomaterial with numerous applications like photocatalysis, fillers, water treatment, color pigmentation, UV absorbance, photosynthesis, and ceramic uses [14,113]. Titania NPs in the colloidal shape obtained by the hydro-thermal methodology have different applications in diverse fields [14]. Numerous morphologies of titanium dioxide nanoparticles show promise for use in photoelectrochemical (PEC) splitting, water purification, cosmetics, and solar energy conversion. Titania nanostructures can be prepared to report on pollution, environmental issues, and poisoned energy disasters [115]. Researchers from a wide range of fields are very interested in enhancing the photocatalytic and magnetic effects of produced nanocomposites because of their photocatalytic and magnetic qualities [116]. The specific characteristics of materials based on titania are detailed in [14]. Light energy-producing charge carriers in the process cause water and oxygen molecules to react, resulting in the production of hydroxyl and anionic oxygen radicals. Titania is also used for waste degradation, self-washing, and self-decontamination. The photocatalytic system explained in [14].

The optical characteristics of TiO2 nanoparticles are linked to a variety of applications. At the same time, the immensely effective application of TiO2 nanomaterials is occasionally avoided because of its large band gap. Bulk TiO2 nanoparticles in both phases, rutile, and anatase, have a band gap value in the UV region (3.0 eV and 3.2 eV, respectively), which represents a modest part of the sun’s energy (<10%) [99]. Therefore, increasing the optical activity of TiO2 nanoparticles by moving the reaction from the ultraviolet to the visible band is an exceptional achievement used to increase their quality [117]. This goal can be achieved in several ways. In the first place, doping TiO2 nanoparticles with other chemicals can alter their optical properties by decreasing their electrical properties. Second, TiO2’s optical activity in the V region is increased when it is exposed to other vibrant organic or inorganic composites. Third, combining collective oscillations of the electrons in the conduction band of metal nanoparticle surfaces with those in the conduction band of TiO2 nanoparticles can enhance the performance of metal-TiO2 nanocomposites. Additionally, by altering the titania nanomaterial surface with different semiconductors, the charge-transfer characteristics between TiO2 and the immediate environment may be changed, enhancing the functionality of devices based on TiO2 nanomaterials [118].

5.1. Potential Applications

TiO2 is a significant metal oxide with outstanding multifunctional qualities, including great stability in both chemical and photochemical processes, non-toxicity, inexpensiveness, good photocatalytic activity, and electrical, electronic, and optical characteristics employed in different applications for technology developments [14]. TiO2 has several promising uses, as seen in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Illustration of potential applications of TiO2.

5.1.1. Food Packaging

TiO2 NPs present good photocatalytic activity, chemical stability, antibacterial properties, biocompatibility, and UV-blocking properties. When Cs/PEO/Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite films were produced using the solution casting route, implanted Ag and TiO2 NPs in the Cs/PEO (polyethylene oxide) combination enhanced their antibacterial and mechanical qualities. As a result, they were used as a natural preservative in food packaging systems. Positive outcomes like antibacterial activity were noticed when we added Ag/TiO2 NPs to the polymer mixture, which makes it a good candidate for food packaging manufacturing [119].

In addition to those characteristics, new research indicates that coatings based on nano-TiO2 can greatly increase the shelf life of fresh meats and vegetables by photocatalytically generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) when exposed to UV or visible light. For instance, PLA/nano-TiO2 sheets decreased microbial counts, extending the shelf life of pork at ambient temperature and under refrigeration [120]. Furthermore, to its antibacterial properties, nano-TiO2 in packaging matrices is being developed for “smart packaging.” Under light exposure, TiO2 may also serve as an optical indicator and even a triggered reservoir for the controlled release of preservatives [121]. At the same time, there is a current regulatory issue with migration and safety. Although TiO2 is still commonly used in antimicrobial packaging systems, European regulatory bodies have prohibited its use as a direct food additive due to potential genotoxicity. Current research suggests immobilizing TiO2 within polymer matrices or surface-binding it to minimize the release of nanoparticles into food. TiO2 nanoparticles’ antimicrobial qualities and safety considerations in materials that come into contact with food [122].

5.1.2. Agricultural Field

Many applications, including the removal of pollutants, agrichemicals, and agricultural yield enhancement, make use of nano-sized TiO2. The effects on physiological indicators and plant biomass vary according to dosage and size. According to a study, nano-TiO2 reduces iron plaque levels and arsenic aggregation in rice seedlings, lowering the amount of arsenic that remains in the barrier and lowering root absorption [123]. At appropriate dosages, TiO2 nanoparticles can enhance plant physiological performance in addition to remediating pollutants and immobilizing heavy metals. Foliar-sprayed TiO2 NPs (~100 mg kg−1) enhanced net photosynthetic rate, electron transport rate, and ultimate fruit output in stressed tomato plants; however, greater doses started to impair performance [124]. Large-scale, multigenerational, long-season field experiments are still uncommon, nevertheless. Although nano-TiO2 and related metal-oxide nano fertilizers can boost yield and nutrient uptake in controlled environments, we warn that there are still unanswered questions regarding their long-term ecological effects, disruption of the soil microbiome, and accumulation of nanoparticles in edible tissues [125].

5.1.3. Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells

TiO2 is frequently used in dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) as a photo-anode material because of the good positions of its energy band, resistance versus photo corrosion, low cost, excellent chemo-solubility, and strong light absorption principally in the UV region. Because of their capable photocatalytic activity, hydrogen-activated alterations are highly relevant in metal oxide semiconductor materials [12].

The photo-anode in DSSCs that relies on the H2 treatment in conjunction with thin films of TiO2 NPs that are 11.65 mm thick improves the power conversion efficiency (PCE) by 6.05% [126]. According to the study’s findings, titanium dioxide performance was improved by a Cu-doped TiO2 NPs/graphene complex made using the hydrothermal technique. Different characterization techniques like TEM, FE-SEM, and XRD were employed to analyze the mentioned compound; the final results showed that PCE was enhanced in DSSCs. Graphene doping significantly increased the composite dye loading capacity, which improved the cell’s JSC and PCE [127].

Reports confirm that dye adsorption capability is extremely altered by exposed TiO2 crystal facets. It was discovered that the responsiveness of these exposed facets to absorb dye molecules is further improved by raising their surface section. TiO2 NPs with a higher isoelectric point (IEP) and surface area were produced utilizing a straightforward solvothermal technique. Realistic light scattering enhanced dye loading and dye-sensitized solar cell (DSC) efficiency [128].

TiO2’s remarkable chemical and thermal stability, low cost, and adequate band gap make it a popular choice for DSSC photo-anode materials. To solve the problem of the deficient TiO2 electron mobility, various techniques, including doping and the use of nano-architectures and nanocomposites, were suggested. When compared to bare titania photo-anodes, a nanostructure with increased porosity considerably bettered DSSC performance, increasing efficiency by 18.2% while keeping cell firmness without halting current creation [129]. The target of current DSSC research is to move TiO2 activity from UV absorption alone to the visible spectrum. Non-metal doping (N, S), plasmonic coupling with Au or Ag nanoparticles, and the formation of type-II or Z-scheme heterojunctions with semiconductors that have a smaller band-gap are some strategies. These methods improve photocurrent and PCE directly by reducing electron-hole recombination and expanding the useful solar spectrum [14]. Morphological control is an additional strategy. Hierarchical TiO2 nano-architectures (nanotubes, nanorods, and three-dimensional porous “forest” structures) improve charge transfer and elevate Jsc by increasing dye loading, light scattering, and electrolyte contact area. According to [14], these structured scaffolds are also being included into flexible and tandem systems, such as hybrid and perovskite-sensitized solar cells, where TiO2 continues to function as a stable, inexpensive electron transport layer.

5.1.4. Wastewater Treatment

By employing a precipitation process to separate harmful organic molecules from air and water, photocatalysis—which mostly uses titania nanomaterials—is used for wastewater treatment and water purification. The photocatalyst Fe2O3-Ag2O-TiO2 NPs were produced through various procedures, using XRD, FWSEM, FTIR, TEM, and EDS to demonstrate remarkable efficacy in eliminating flumioxazin from water samples. Photocatalytic tests have demonstrated that Fe-Ag co-doped TiO2 nanoparticles significantly increased activity under acidic, basic, and neutral conditions when used for a consistent amount of time. However, even after several days of trials, no activity was seen without the addition of Fe-Ag co-doped TiO2 NPs [127,130].

An eco-friendly and green process to isolate water-soluble contaminants into non-toxic complexes was employed by manufacturing porous silica microspheres with trapped titania NPs for wastewater treatment utilizing heterogeneous photocatalysis. Results disclosed that the benefit of merely extracting the photocatalyst from the reaction solution was contemplated to enhance photocatalytic activity [131]. It was found that high concentrations of toxic substances include a considerable number of heavy metals stored in our living organisms. TiO2 NPs are utilized for the elimination of these metals.

By mixing TiO2 NPs in different concentrations into polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)-polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP) fiber membrane, the phase inversion approach was applied for copper removal. Techniques like SEM and EDX were applied to characterize the fabricated fibers, which demonstrate enhanced membrane permeability, antifouling properties, flux copper absorption and rejection, and hydrophilicity with mixed TiO2 NPs. A constructed hybrid PVDF-PVP layer containing 1.0 wt.% was effectively used for wastewater curation [132].

TiO2-based photocatalytic membranes, floating photocatalyst sheets, and magnetically retrievable TiO2 composites are examples of recent developments. According to [133], these designs allow the recovery and reuse of the catalyst following treatment, hence reducing secondary nanoparticle pollution and advancing the technique towards scalable water treatment, unlocking TiO2 nanoparticles’ potential for bioremediation and sustainable agriculture. Under visible light, modified TiO2 systems, such as TiO2/g-C3N4, N-doped TiO2, or TiO2 combined with noble metals, can function and have shown remarkable removal efficiency (typically >80–90%) for dyes, pharmaceuticals, persistent organic pollutants, and even endocrine disruptors in wastewater. Reactor design for large-scale solar photocatalysis, poor quantum yield in sunshine, and photocatalyst deactivation are the key engineering hurdles that still exist [134].

5.1.5. Biomedical Applications

TiO2 nanomaterials are employed as photocatalysts for self-cleaning and self-disinfection in a variety of surface coating applications. As a result of their photo-accelerated superhydrophobicity, anti-fogging effect, and non-toxicity, titanium dioxide is commonly utilized in cleaning ecosystems. The biomedical treatment using TiO2 NPs, a manufactured solution of leaf extract from Salvia spinosa, provides a stable, heat-resistant, and innocuous substance that is suitable for treating juvenile leukemia because of its anti-Molt-4 cell cytotoxicity [135].

Fibroblast union rose, and gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial biofilm decreased when TiO2 nanoparticles were added to hybrid diamond-like carbon (DLC) films. Due to its photocatalytic implementation, it has a self-cleaning result. Additionally, it was discovered that the incorporation of TiO2 into DLC films increased cell survival and the anti-inflammatory reaction, with no apparent cytotoxic activity. This demonstrates the potential of TiO2 DLC as a biocompatible coating material for biomedical composites [136].

TiO2 nanoparticles are being studied as photosensitizers in photodynamic treatment (PDT) for cancer in addition to antimicrobial coatings. TiO2 can produce reactive oxygen species that cause cancer cells to undergo apoptosis in vitro when activated by UV or visible light. Because of its optical/electrical characteristics and versatility in surface functionalization, TiO2 has also been used in targeted drug delivery and theranostic (therapy + diagnostic) platforms. TiO2 nanoparticles: Unlocking Their Potential for Bioremediation and Sustainable Agriculture [133]. Aggregation, protein corona formation, biodistribution, long-term clearance, and oxidative stress-mediated toxicity must all be carefully controlled for biological translation. To enhance in vivo compatibility and decrease off-target harm, surface modification (such as PEGylation or biomolecule coating) is frequently suggested [133].

5.1.6. Gas Sensing

Since SO2 is recognized as a toxic and dangerous gas, its high concentration increases the dangers to the environment and human health. Common sensors for SO2 gas employing pure TiO2 NPs have operational restrictions like low response, selectivity, high operating temperature, and stability. To overcome this issue, a new method is recommended utilizing a combination of TiO2 NPs with a polymer of non-conducting polyvinyl formal (PVF). Compared to conventional pure TiO2 sensors, the novel nanocomposite PVF/TiO2 sensor presents advanced choosiness, higher sensitivity at minimal temperatures, and quick reaction times. The effectiveness of this sensor is approved by different characterization techniques like XRD, SEM, FTIR, and TGA. The manufactured chemiresistive nanocomposite sensor reveals outstanding performance in identifying SO2 gas with quick reply and retrieval times, good selectivity, and durable solidity. Furthermore, it poses other benefits like simple synthesis, low power usage, portability, cost-effectiveness, and suitability for eco-friendly monitoring applications [137].

Titanium-based mechanisms are advocated for gas detection because of their capability to react to hydrogen and organic gases, and since they simply change resistance when detecting various gas species. Graphene oxide (GO-TiO2) nanostructures were investigated for photocatalytic accomplishment enhancement and gas sensor development. Excellent sensitivity and preference for oxygen and hydrogen concentrations were improved by loading TiO2 to reduced graphene oxide (rGO) sheets [138].

In addition to SO2 and H2, modern TiO2-based gas sensors can detect NO2, CO, humidity, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Nanostructuring (nanotubes, nanorods) and catalytic doping with Pd, Pt, or Au can significantly increase sensitivity and lower the operating temperature toward room temperature. Gas adsorption on TiO2 surfaces changes the density of chemisorbed oxygen species, which in turn changes the film resistance [14]. Combining TiO2 with conductive 2D materials like WS2, MoS2, or reduced graphene oxide (rGO) creates heterojunctions that speed up electron transmission and charge separation. TiO2/rGO hybrids, for instance, have shown quick response/recovery (seconds) for hydrogen at or close to room temperature, indicating great promise for low-power, portable environmental and industrial monitoring [14].

5.1.7. Charge Storage Devices (Capacitors)

To increase the mechanical strength and ionic conductivity of solid electrolytes, an accumulation of filling ceramics into electrolytes was employed. Nanocomposite Solid electrolytes (NCSEs) were manufactured from a combination of titanium and potassium iodo-plumbite. Different techniques like SEM, EDS, FTIR, and XRD were used, showing better ionic conductivity, high amorphous nature, and slight activation energy [139].

In electrochemical energy storage devices like lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitors, TiO2 nanoparticles are also crucial. Nanotubular TiO2 and anatase can function as stable anode or pseudocapacitive materials with high safety and cycle stability. Electronic conductivity, specific capacitance, and rate capability are greatly increased by doping TiO2 with aliovalent cations (e.g., Nb, V) or combining it with conductive carbons (graphene, carbon nanotubes [140]. Flexible and wearable energy systems are becoming more popular. For small, flexible power modules in sensors and portable electronics, hybrid solid-state electrolytes and printable TiO2-based electrodes are being investigated [140].

5.1.8. Degradation of Dyes and Other Toxic Pollutants

A noxious herbicide 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic (2,4-D), is applied for fighting wildflowers in the agronomy sector. TiO2 nanoparticles are frequently used for photocatalytic removal of contaminants due to their excellent photocatalytic capability, chemical constancy, affordability, and non-harmfulness [141]. Fe-doped TiO2 NPs were created and exploited to photocatalytically break down 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) from water when exposed to UV and sunshine. FTIR and XRD procedures were utilized to characterize the generated photocatalyst. Results revealed that the highest elimination of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) was completed in pH levels that were both acidic and neutral. It was found that the removal efficiency was enhanced by raising the catalyst quantity [142]. With dye degradation of up to 88% in 10 min under xenon lamp irradiation, a synthetic TiO2 nanoparticle on polyethylene terephthalate (PET) nanofibers demonstrated increased photocatalytic activity, demonstrating the versatility of TiO2/PET nanofibers [143].

Because of their non-toxic, affordable, photo-stable, and reusable properties, TiO2 semiconductors are considered common photocatalysts. Minerals, CO2, and H2O are produced when chemical contaminants like colors and microbes are reduced. It showed that the photo-degradation activity of metal-doped titania was superior to that of undoped or pure titania. According to the findings, methylene blue and natural dyes were degraded by 95% and 90%, respectively, when metal-doped titania was used [144].

Emerging contaminants including hormones, antibiotics, microplastics, medicines, and persistent organic pollutants are also the focus of recent research. Using simulated solar light, visible-light-responsive TiO2 composites (such as N-doped TiO2 and TiO2/g-C3N4) degrade these compounds by >80–90%, which is crucial for actual environmental conditions [134]. TiO2 photocatalysts are being immobilized on supports such glass beads, polymer fibers, floating foams, or magnetic carriers in order to increase reusability and prevent the release of secondary nanoparticles. Realistic wastewater treatment deployment is shown by the steady performance of pilot-scale solar reactors employing immobilized TiO2 across several cycles [133].

5.1.9. Thermal Energy Storage

The use of thermal energy storage materials with low-cost heat transmission and storage forms is necessary to meet the growing demand for thermal energy; graphene hybrid materials are essential for energy storage applications. A hybrid GO/TiO2 NPs were prepared and characterized by different techniques like TGA, FTIR, EDX, and ESEM. Findings showed that hybrid nanoparticles have a higher heat capacity than single nanoparticles. Results indicated that a new thermal energy storage (TES) compound was elaborated with enhanced specific heat, thermal solidity, and heat capacity, making hybrid nanofluid a suitable choice for thermal energy storage devices [145]. The best option for thermal energy is paraffin, and TiO2 NPs can enrich its thermal characteristics. This result was confirmed by employing different techniques: TGA, thermal properties analyzers, and FTIR without modifying its thermal decomposition and chemical structure [146].

In addition to paraffin/GO hybrids, TiO2 nanoparticles are added to solar-thermal heat transfer fluids, molten-salt nanofluids, and phase change materials (PCMs) to increase sun absorption, specific heat capacity, and thermal conductivity. as optimized TiO2 nanofluids are utilized in solar-thermal loops, experimental investigations show 10–20% increases in the heat transfer coefficient as compared to the base fluid [14]. The capacity of surface-modified TiO2 (such as silica-coated or surfactant-stabilized) to withstand agglomeration and sedimentation during several heating/cooling cycles is crucial for long-term stability. These PCM composites and tailored nanofluids are now being researched for hybrid photovoltaic-thermal (PVT) panels, HVAC buffering, and building-integrated thermal energy storage [140].

A summary of the nine applications of TiO2 nanoparticles, grouped according to their primary industrial or scientific sectors are detailed in the subsequent Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparative between the different applications of TiO2 applications.

6. Conclusions

Since titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles have special structural, optical, and photocatalytic qualities, they have become a key component of the rapidly developing area of nanotechnology. TiO2 particles’ surface area, reactivity, and energy band configurations have all been greatly improved by their transformation into nanoscale particles, opening up a variety of uses in the sectors of industry, biomedicine, energy, and the environment. Sol-gel, hydrothermal, solvothermal, microwave-assisted, and green synthesis are some of the synthesis techniques described in this study. Each offers unique benefits for regulating the size, shape, and crystalline phase of TiO2 nanoparticles.

The two main crystalline phases of TiO2, anatase and rutile, differ in their band gap energy, crystal structure, and photocatalytic efficacy, which makes them appropriate for particular applications. It was discussed that methods such as Raman analysis, FTIR, UV-vis spectroscopy, and XRD are essential for describing these characteristics. Notably, doping and surface changes have increased TiO2’s responsiveness to the visible spectrum, expanding its usefulness, while its optical band gap in the UV region increases its potential as a photocatalyst.

TiO2 nanoparticles show great promise in gas sensing, dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs), thermal energy storage, food packaging, wastewater treatment, and photocatalysis. Their relevance in biological applications, including cancer therapy and antimicrobial coatings, is further cemented by their non-toxic and biocompatible nature. Even with limitations like broadband gaps and agglomeration tendencies, new developments—particularly in hybridization and composite formation—keep expanding the potential of TiO2 nanomaterials. In summary, the development of TiO2 nanostructures emphasizes the material’s flexibility and functional variety, highlighting its importance in advancing innovative material science and sustainable technologies.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU252128].

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. (please specify the reason for restriction, e.g., the data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU252128].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. This work is original and not submitted elsewhere. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Form/Explanation |

| 2,4-D | 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (an herbicide) |

| CVD | Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| Cs | Chitosan |

| DEA | Diethanolamine |

| DLC | Diamond-Like Carbon |

| DSSCs/DSCs | Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells |

| EDS/EDX | Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| Eg | Energy Band Gap |

| e− CB | Electron in the Conduction Band |

| ESEM | Environmental Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FE-SEM | Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| FWHM | Full Width at Half Maximum |

| GO | Graphene Oxide |

| h+ VB | Positive Hole in the Valence Band |

| HPEI | Hyperbranched Polyethyleneimine |

| HRTEM | High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning |

| hv | Photon Energy |

| IEP | Isoelectric Point |

| JCPDS | Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (now ICDD) |

| JSC | Short-Circuit Current Density |

| NCSEs | Nanocomposite Solid Electrolytes |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| PANI | Polyaniline |

| PCE | Power Conversion Efficiency |

| PCMs | Phase Change Materials |

| PEC | Photoelectrochemical |

| PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| PEO | Polyethylene Oxide |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| PDT | Photodynamic Therapy |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene Fluoride |

| PVF | Polyvinyl Formal |

| PVP | Polyvinyl Pyrrolidone |

| PVT | Photovoltaic-Thermal |

| rGO | Reduced Graphene Oxide |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SAED | Selected Area Electron Diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| SERS | Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering |

| SF | Stacking Fault |

| TC | Texture Coefficient |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| TES | Thermal Energy Storage |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| Ti(OBu)4 | Titanium(IV) n-butoxide |

| TTIP | Titanium Tetraisopropoxide |

| Polymorph | A substance that can crystallize into more than one structure. |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

References

- Aliofkhazraei, M. Handbook of Nanoparticles; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Macwan, D.P.; Dave, P.N.; Chaturvedi, S. A review on nano-TiO2 sol–gel type syntheses and its applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 3669–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, T.; Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Luo, W.; Wu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Layered deposited MoS2 nanosheets on acorn leaf like CdS as an efficient anti-photocorrosion photocatalyst for hydrogen production. Fuel 2024, 368, 131621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajareh Haghighi, F.; Mercurio, M.; Cerra, S.; Salamone, T.A.; Bianymotlagh, R.; Palocci, C.; Romano Spica, V.; Fratoddi, I. Surface modification of TiO2 nanoparticles with organic molecules and their biological applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 2334–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellami, H.; Akinyemi, M.O.; Gdoura-Ben Amor, M.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Mthiyane, D.M.N. Structural and optical characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles synthesized using Globularia alypum leaf extract and the antibacterial properties. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermakov, A.Y.; Uimin, M.A.; Boukhvalov, D.W.; Minin, A.S.; Kleinerman, N.M.; Naumov, S.P.; Volegov, A.S.; Starichenko, D.V.; Borodin, K.I.; Gaviko, V.S.; et al. Magnetism and Electronic State of Iron Ions on the Surface and in the Core of TiO2 Nanoparticles. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J. The synthesis and applications of TiO2 nanoparticles derived from phytochemical sources. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 106, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomen, S.; Asuliman, B.; Alsuwaidan, H.; Al-Madhi, F.; Hafiz, R. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) in herbal and health products registered by Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA): A descriptive study. Next Res. 2024, 1, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, J.; Cho, J.; Mishra, Y.K. Photocatalytic TiO2 nanomaterials as potential antimicrobial and antiviral agents: Scope against blocking the SARS-COV-2 spread. Micro Nano Eng. 2022, 14, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, T.; Rajendran, S.; Natarajan, S.; Vinayagam, S.; Rajamohan, R.; Lackner, M. Environmental fate and transformation of TiO2 nanoparticles: A comprehensive assessment. Alexandria Eng. J. 2025, 115, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T.-H.; Do, H.-B.; Pham, L.D.; Phan, T.X.; Chen, W.-Z.; Lan, L.-W.; Lin, H.-J.; Nguyen, V.-H.; Dong, C.-L.; Kumar, A.S.K.; et al. Efficient photoanode with a MoS2/TiO2/Au nanoparticle heterostructure for ultraviolet-visible photoelectrocatalysis. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 385703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, K.V.; Srivastava, P.; Srivastava, A.; Maurya, R.K.; Singh, Y.P.; Srivastava, A. 1D TiO2 photoanodes: A game-changer for high-efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 4789–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, C. Band gap energy and lattice distortion in anatase TiO2 thin films prepared by reactive sputtering with different thicknesses. Materials 2025, 18, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, N.; Kallem, P.; Rehman, Z.U.; Imran Khan, M.; Kumar Gupta, R.; Tahseen, T.; Mushtaq, Z.; Ejaz, N.; Shanableh, A. Recent trends of titania (TiO2) based materials: A review on synthetic approaches and potential applications. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2024, 36, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggerty, J.E.S.; Schelhas, L.T.; Kitchaev, D.A.; Mangum, J.S.; Garten, L.M.; Sun, W.; Stone, K.H.; Perkins, J.D.; Toney, M.F.; Ceder, G.; et al. High-fraction brookite films from amorphous precursors. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.F.; Zhang, Z.W.; Hu, F.C. Phase stabilities and photocatalytic activities of P/Zn-TiO2 nanoparticles able to operate under UV-vis light irradiation. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 465, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meacock, G.; Taylor, K.A.; Knowles, M.J.; Himonides, A. The improved whitening of minced cod flesh using dispersed titanium dioxide. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1997, 73, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reghunath, S.; Pinheiro, D.; Kr, S.D. A review of hierarchical nanostructures of TiO2: Advances and applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 3, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Saxena, K.; Goswami, L.P.; Gayathri, J.; Mehta, D.S. Mesoporous Ag–TiO2 based nanocage like structure as sensitive and recyclable low-cost SERS substrate for biosensing applications. Opt. Mater. 2022, 125, 111994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belew, A.A.; Assege, M.A. Solvothermal synthesis of metal oxide nanoparticles: A review of applications, challenges, and future perspectives. Results Chem. 2025, 16, 102438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Gázquez, P.J.; Muñoz-Portero, M.J.; Blasco-Tamarit, E.; Sánchez-Tovar, R.; García-Antón, J. Synthesis and applications of TiO2/ZnO hybrid nanostructures by ZnO deposition on TiO2 nanotubes using electrochemical processes. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2023, 39, 1153–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Hernández-Reséndiz, J.R.; Cruz-Ramírez, M.; Velázquez-Castillo, R.; Escobar-Alarcón, L.; Ortiz-Frade, L.; Esquivel, K. Au-TiO2 synthesized by a microwave-and sonochemistry-assisted sol-gel method: Characterization and application as photocatalyst. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seman, N.; Tarmizi, Z.I.; Ali, R.R.; Taib, S.H.M.; Salleh, M.S.N.; Zhe, J.C.; Sukri, S.N.A.M. Preparation Method of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles and Its Application: An Update. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1091, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathumba, P.; Kuvarega, A.T.; Dlamini, L.N.; Malinga, S.P. Synthesis and characterisation of titanium dioxide nanoparticles prepared within hyperbranched polyethylenimine polymer template using a modified sol–gel method. Mater. Lett. 2017, 195, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, B.K.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, D. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica leaf extract and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 124, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachit, W.; Ait Ahsaine, H.; Ramzi, Z.; Touhtouh, S.; Goncharova, I.; Benkhouja, K. Photocatalytic activity of anatase-brookite TiO2 nanoparticles synthesized by sol gel method at low temperature. Opt. Mater. 2022, 129, 112256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wach, A.; Zou, X.; Wojtaszek, K.; Kayser, Y.; Garlisi, C.; Palmisano, G.; Sá, J.; Szlachetko, J. Towards understanding the TiO2 doping at the surface and bulk. X-Ray Spectrom. 2023, 152, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarbrough, R.; Davis, K.; Dawood, S.; Rathnayake, H. A sol-gel synthesis to prepare size and shape-controlled mesoporous nanostructures of binary (II–VI) metal oxides. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 14134–14146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatou, M.A.; Syrrakou, A.; Lagopati, N.; Pavlatou, E.A. Photocatalytic TiO2-Based Nanostructures as a Promising Material for Diverse Environmental Applications: A Review. Reactions 2024, 5, 135–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokov, D.; Jalil, A.T.; Chupradit, S.; Suksatan, W.; Ansari, M.J.; Shewael, I.H.; Valiev, G.H.; Kianfar, E. Nanomaterial by Sol-Gel Method: Synthesis and Application. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 5, 135–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Preparation, Synthesis and Application of Sol-Gel Method. Vidyasirimedhi Inst. Sci. Technol. 2020, 1, 506–510. [Google Scholar]

- Mariño-Gámez, A.E.; Acosta-González, G.E.; Pech-Canul, M.I.; Hernández, M.B.; García-Villarreal, S.; Zambrano-Robledo, P.; Vera Barrios, B.S.; Aguilar-Martínez, J.A. Influence of high energy ball milling on structural, microstructural and optical properties of TiO2 nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 3362–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, V.; Kurajica, S.; Očko, T. Development of phases in the sol-gel derived mixed-metal-oxide (Al2O3–TiO2–ZnO) functional sorbent material. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 29388–29401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Vega, A.; Agustín-Sáenz, C.; O’Dell, L.A.; Brusciotti, F.; Somers, A.; Forsyth, M. Properties of hybrid sol-gel coatings with the incorporation of lanthanum 4-hydroxy cinnamate as corrosion inhibitor on carbon steel with different surface finishes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 561, 149881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; He, P.; Wei, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, C.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, H.; Kowalska, E.; Dong, S. Three-dimensional monodispersed TiO2 microsphere network formed by a sub-zero sol-gel method. Mater. Lett. 2020, 268, 127592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambaza, S.S.; Maity, A.; Pillay, K. Polyaniline-Coated TiO2 Nanorods for Photocatalytic Degradation of Bisphenol A in Water. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 29642–29656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, M.; Ghosh, A.K. An investigation on optimization of instantaneous synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles and it’s thermal stability analysis in PP-TiO2 nanocomposite. Solid State Sci. 2021, 120, 106707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.Y.; Mahmoud, Z.H.; Abdullaev, S.; Ali, F.K.; Ali Naeem, Y.; Mzahim Mizher, R.; Morad Karim, M.; Abdulwahid, A.S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Habibzadeh, S.; et al. Nano titanium oxide (nano-TiO2): A review of synthesis methods, properties, and applications. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Attafi, K.; Mezher, H.A.; Hammadi, A.F.; Al-Keisy, A.; Hamzawy, S.; Qutaish, H.; Kim, J.H. Solvothermally Synthesized Hierarchical Aggregates of Anatase TiO2 Nanoribbons/Nanosheets and Their Photocatalytic–Photocurrent Activities. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astaraki, H.; Masoudpanah, S.M.; Alamolhoda, S. Effects of ethylene glycol contents on phase formation, magnetic properties and photocatalytic activity of CuFe2O4/Cu2O/Cu nanocomposite powders synthesized by solvothermal method. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostas, A.M.; Suciu, R.-C.; Roşu, M.-C.; Turza, A.; Cosma, D.-V.; Tripon, S.; Fort, C.I.; Danciu, V.; Baia, M.; Bocirnea, A.; et al. Annealing temperature, a key factor in shaping Ag-decorated TiO2 aerogels as efficient visible-light photocatalysts. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 337, 130557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, J.; Priyadarshini, A.; Panda, S.; Hajra, S.; Das, N.; Vivekananthan, V.; Mistewicz, K.; Samantray, R.; Joon Kim, H.; Sahu, R. Metal–Organic Frameworks: Synthesis Methods and Multifunctional Applications. Energy Technol. 2025, 13, 2402354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S.; Moon, B.; Park, J.-H.; Chung, S.; Son, S.-M. Synthesis of nanocrystalline TiO2 in toluene by a solvothermal route. J. Cryst. Growth 2003, 254, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Q.; Wu, J. Synthesis of Nanoparticles via Solvothermal and Hydrothermal Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 295–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uematsu, M.; Franck, E.U. Static Dielectric Constant of Water and Steam. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1981, 9, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payakgul, W.; Mekasuwandumrong, O.; Pavarajarn, V.; Praserthdam, P. Effects of reaction medium on the synthesis of TiO2 nanocrystals by thermal decomposition of titanium (IV) n-butoxide. Ceram. Int. 2005, 31, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Fujishiro, Y.; Wu, J.; Aki, M.; Sato, T. Synthesis and photocatalytic properties of fibrous titania by solvothermal reactions. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2003, 137, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M. Synthesis of Fe/TiO2 photocatalyst with nanometer size by solvothermal method and the effect of H2O addition on structural stability and photodecomposition of methanol. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2003, 197, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Conti, M.C.M.D.; Dey, S.; Pottker, W.E.; La Porta, F.A. An overview into advantages and applications of conventional and unconventional hydro(solvo)thermal approaches for novel advanced materials design. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 23, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, J.; Kroczewska, M.; Baluk, M.; Sowik, J.; Mazierski, P.; Zaleska-Medynska, A. Morphology control through the synthesis of metal-organic frameworks. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 314, 102864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazim, T.Q.; Kawsar, M.; Sahadat Hossain, M.; Bahadur, N.M.; Ahmed, S. Hydrothermal synthesis of nano-metal oxides for structural modification: A review. Next Nanotechnol. 2025, 7, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, C.F.; Braga, T.L.; Rossin, A.R.S.; Radovanovic, E.; Dragunski, D.C.; Caetano, W.; Muniz, E.C. Chapter 30—Functionalized Nanofibers for Protective Clothing Applications; Deshmukh, K., Pasha, S.K.K., Barhoum, A., Mustansar Hussain, C.B.T.-F.N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 867–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Mohanty, S. A comprehensive review on piezoelectric inks: From concept to application. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 2024, 366, 114939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, D.S.; Roy, A. Synthesis of Bimetallic Nanoparticles and Applications—An Updated Review. Crystals 2023, 13, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzzeka, C.; Goldoni, J.; Lenzi, G.G.; Bagatini, M.D.; Colpini, L.M. SPhotocatalytic action of Ag/TiO2 nanoparticles to emerging pollutants degradation: A comprehensive review. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2024, 8, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]