LiCl@C-BMZIF Porous Composites: Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and the Effects of Carbonization Temperature and Salt Loading on Thermochemical Energy Storage

Abstract

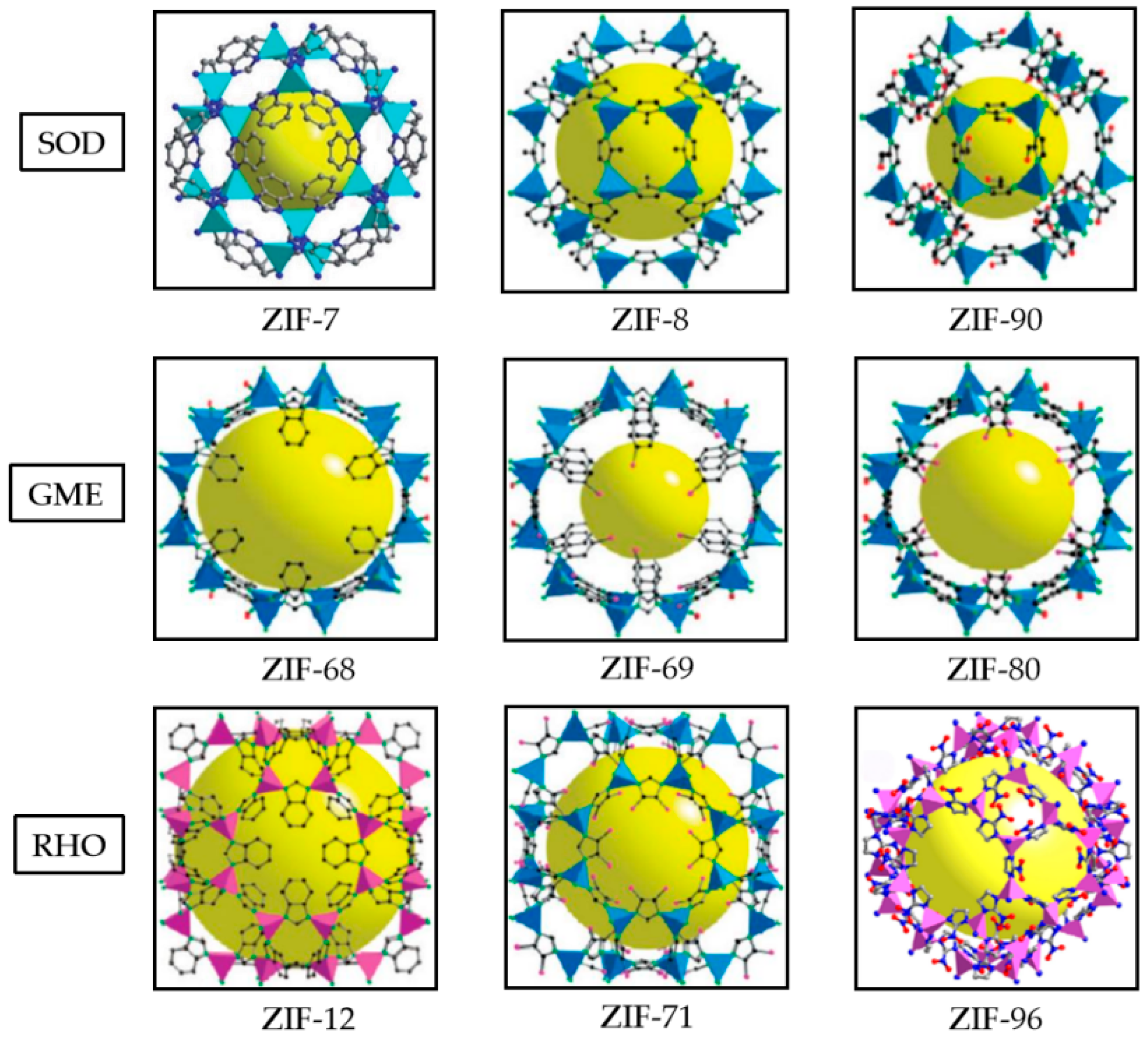

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Experimental Reagents and Experimental Equipment

2.1.1. Experimental Material

2.1.2. Instrumentation

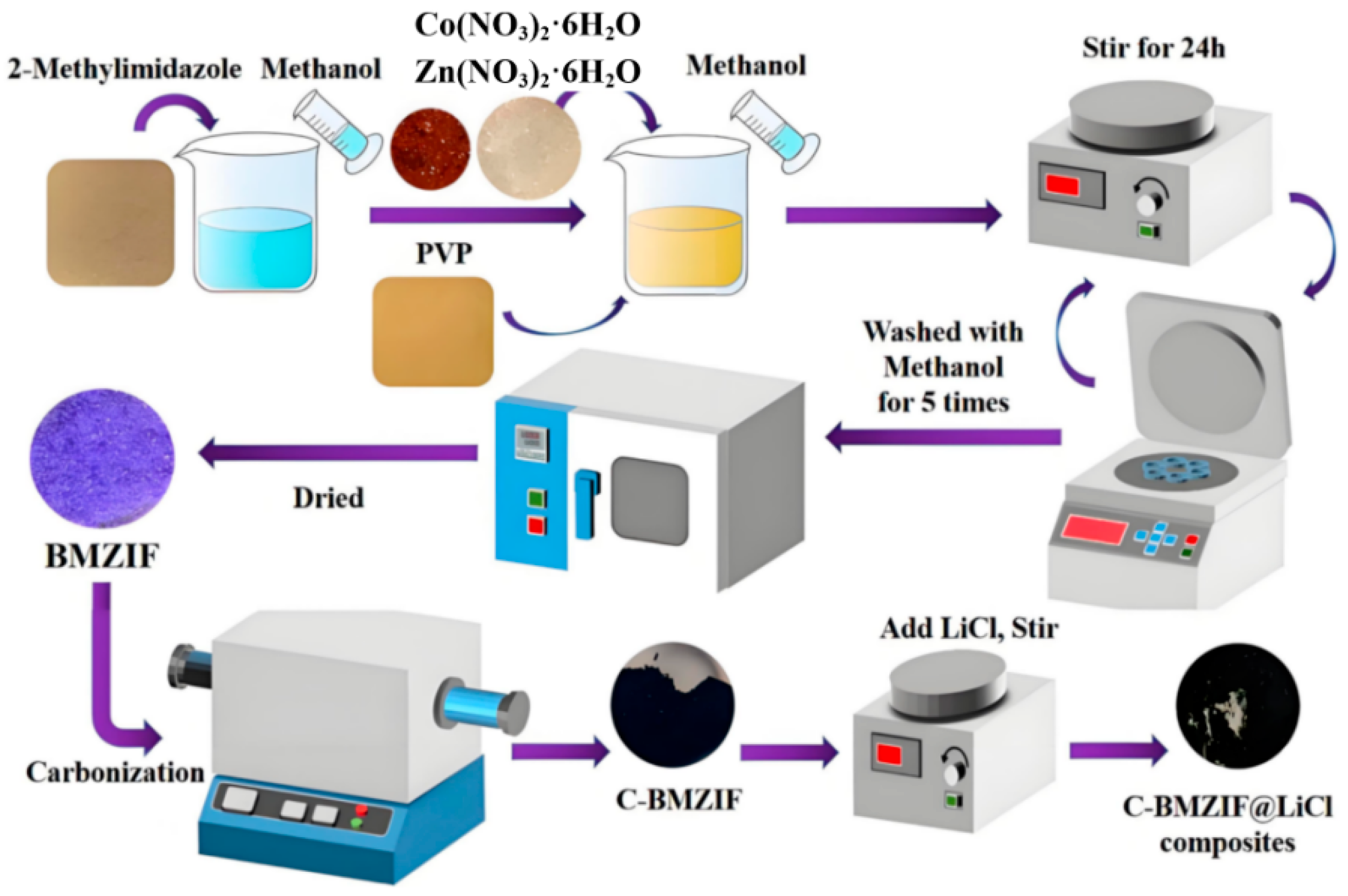

2.2. Synthesis of Porous Matrix “In-Salt” Composite Material

2.2.1. Synthetic Method

2.2.2. Synthetic Procedure

2.3. Characterization Methods

2.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

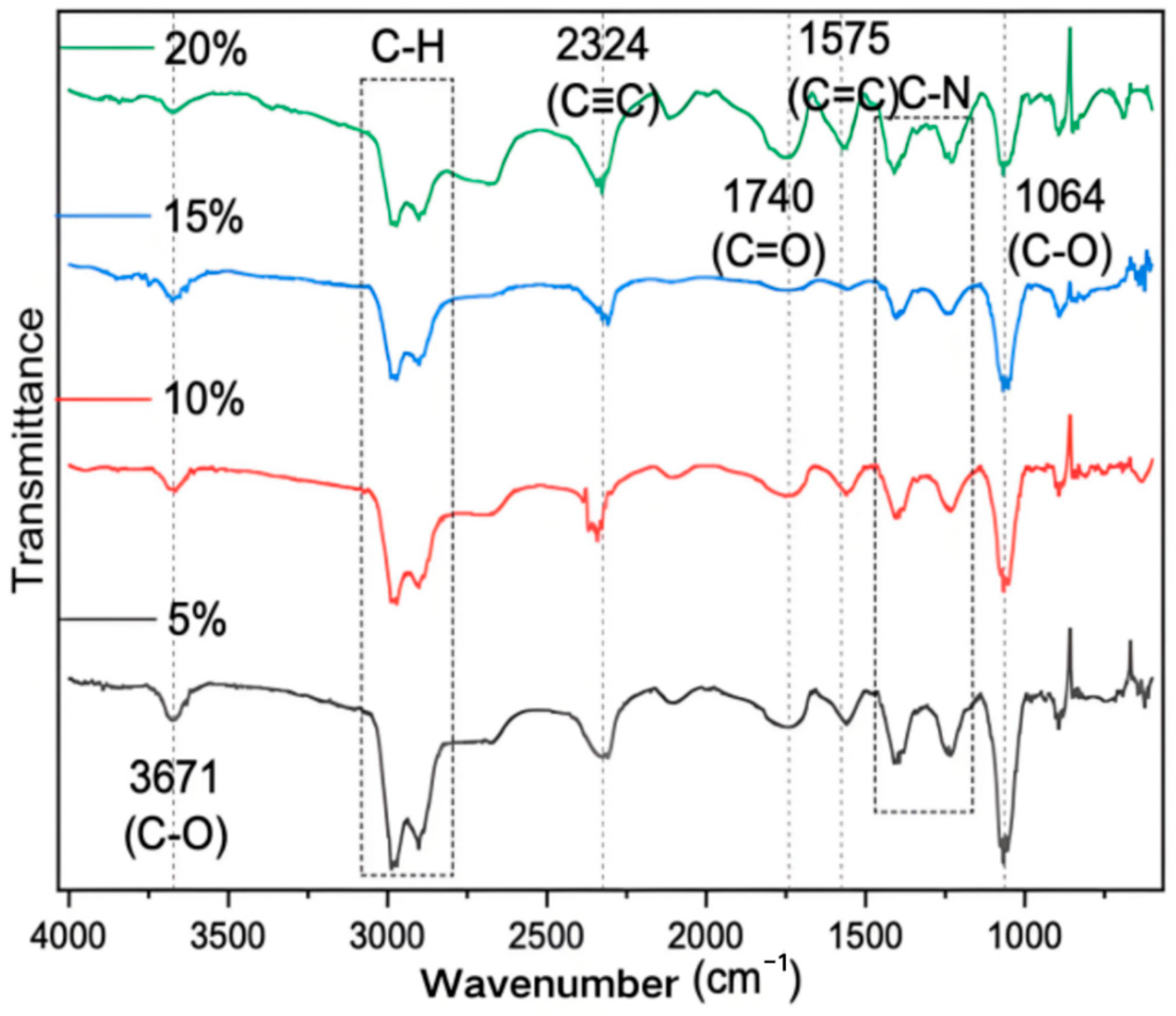

2.3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3.4. Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP)

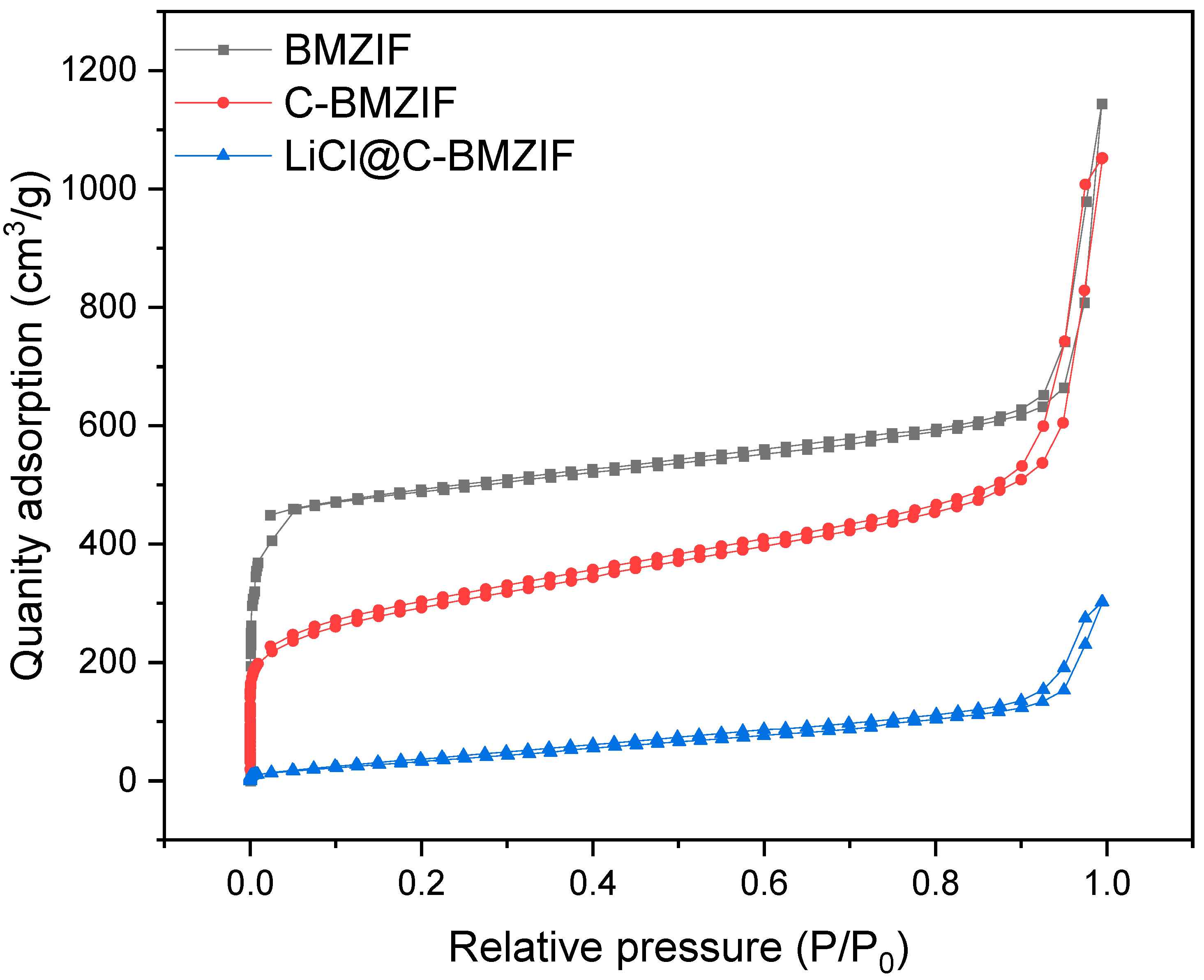

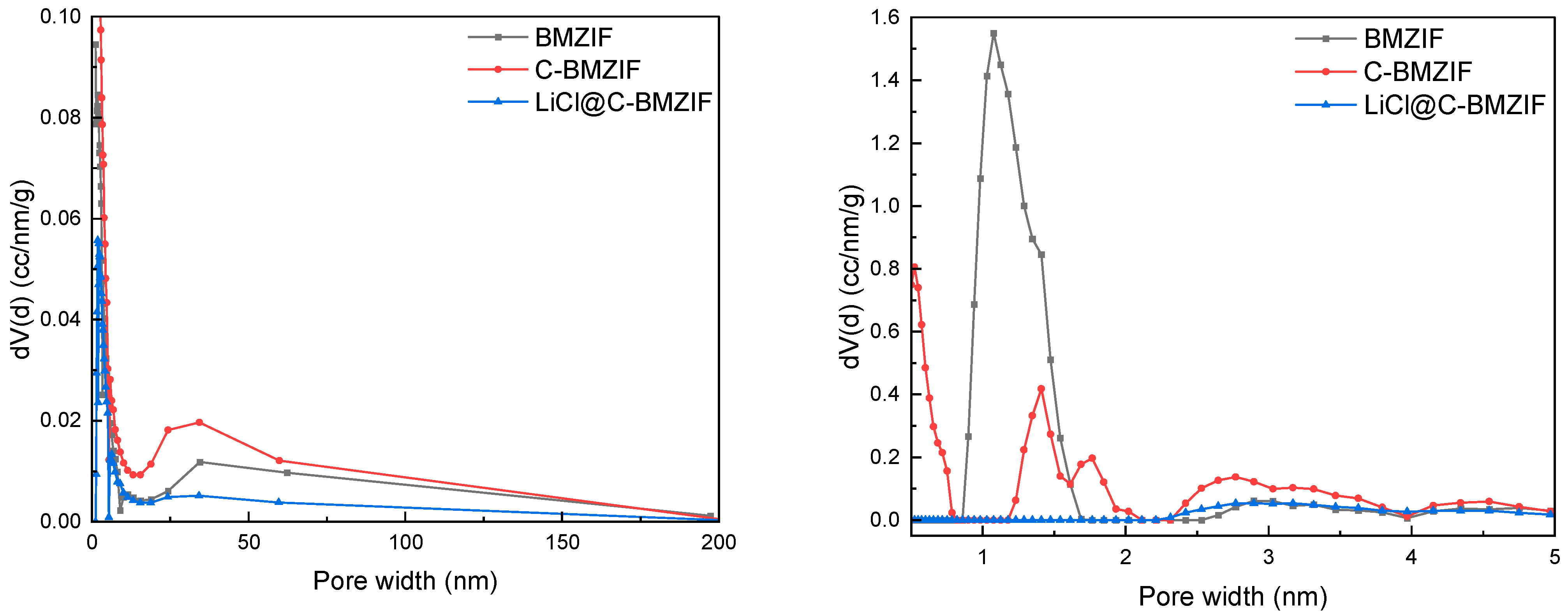

2.3.5. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET)

- represents the saturation vapor pressure of the adsorbing gas;

- denotes the volume of gas adsorbed at pressure P;

- signifies the volume of gas for monolayer adsorption;

- is a constant in the BET equation, related to the adsorption energy.

2.4. Test Methods

2.4.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

- (1)

- Temperature ramp from 25 to 250 °C at 5 °C·min−1.

- (2)

- Isothermal step at 250 °C for 20 min.

2.4.2. Water Adsorption Detection

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Series of Samples

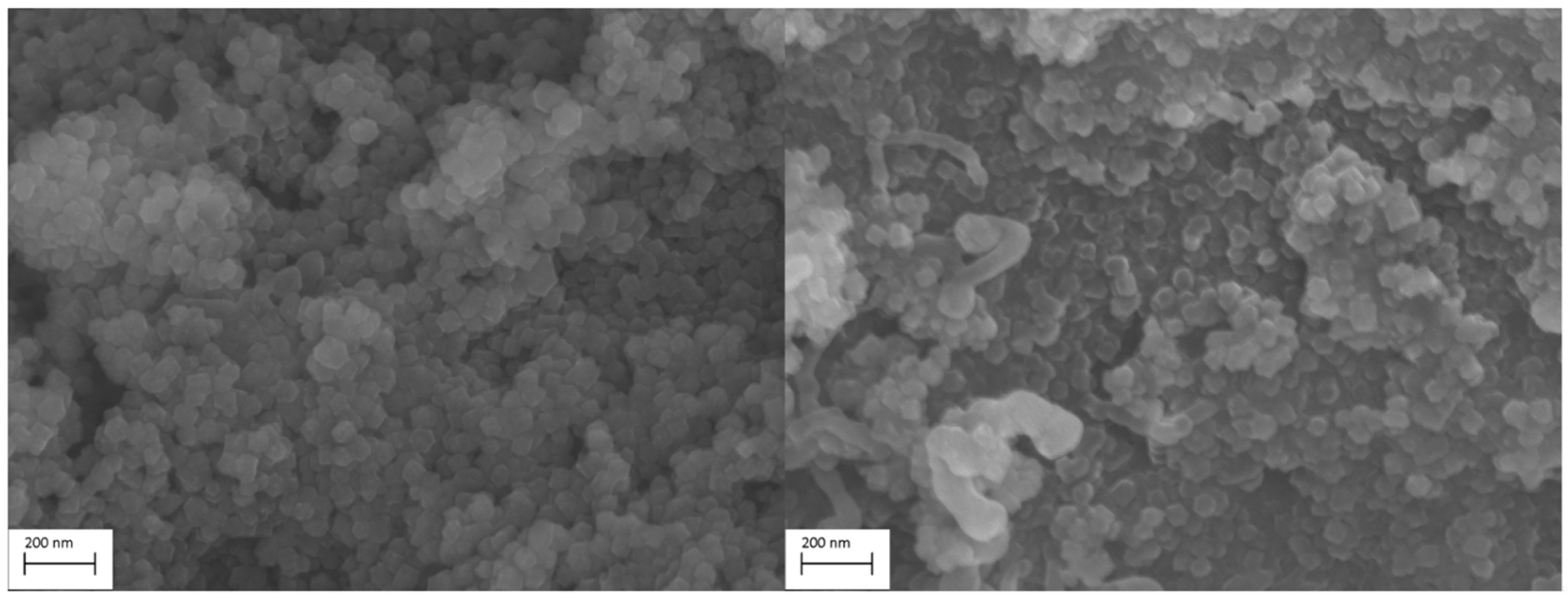

3.2. SEM Results of Different Samples

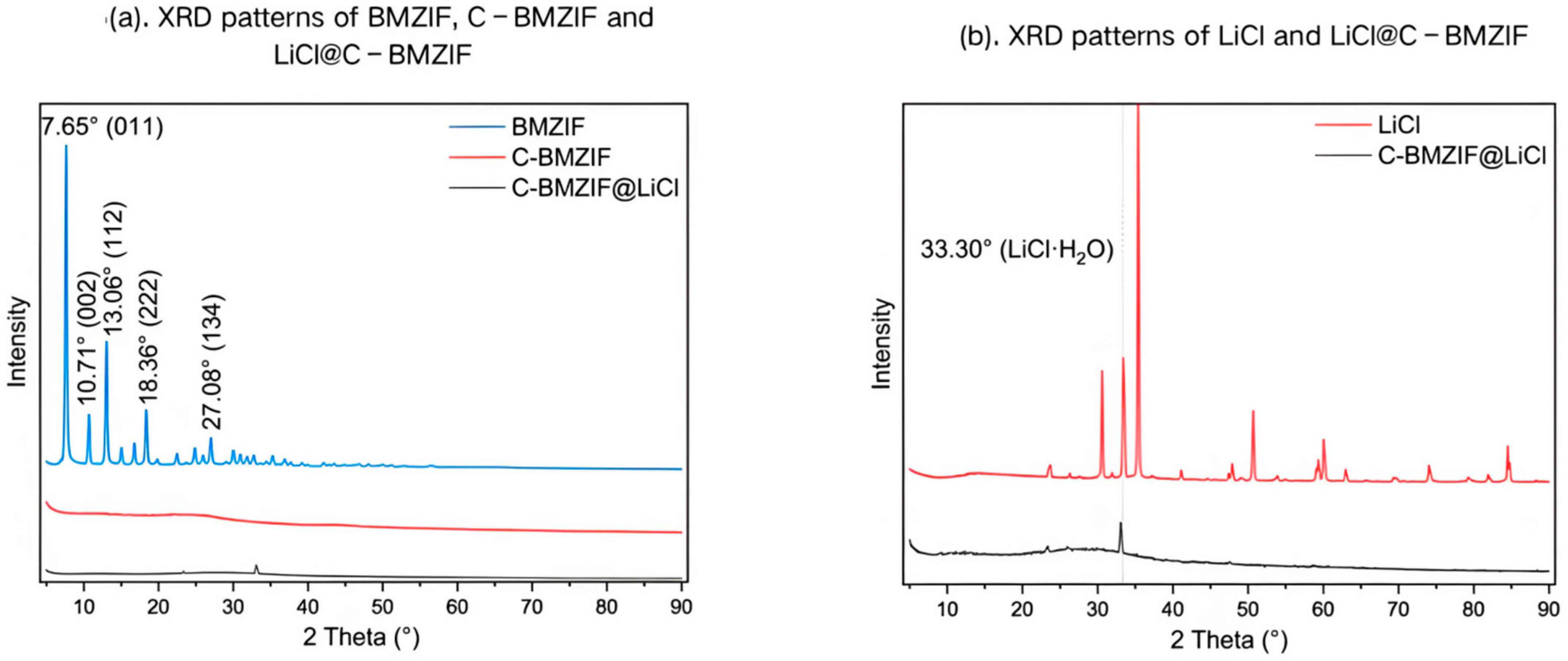

3.3. XRD Results of Different Samples

3.4. FTIR Results of Different Samples

3.5. ICP Results of BMZIF

3.6. BET Results of Different Samples

3.7. TGA Results of Different Samples

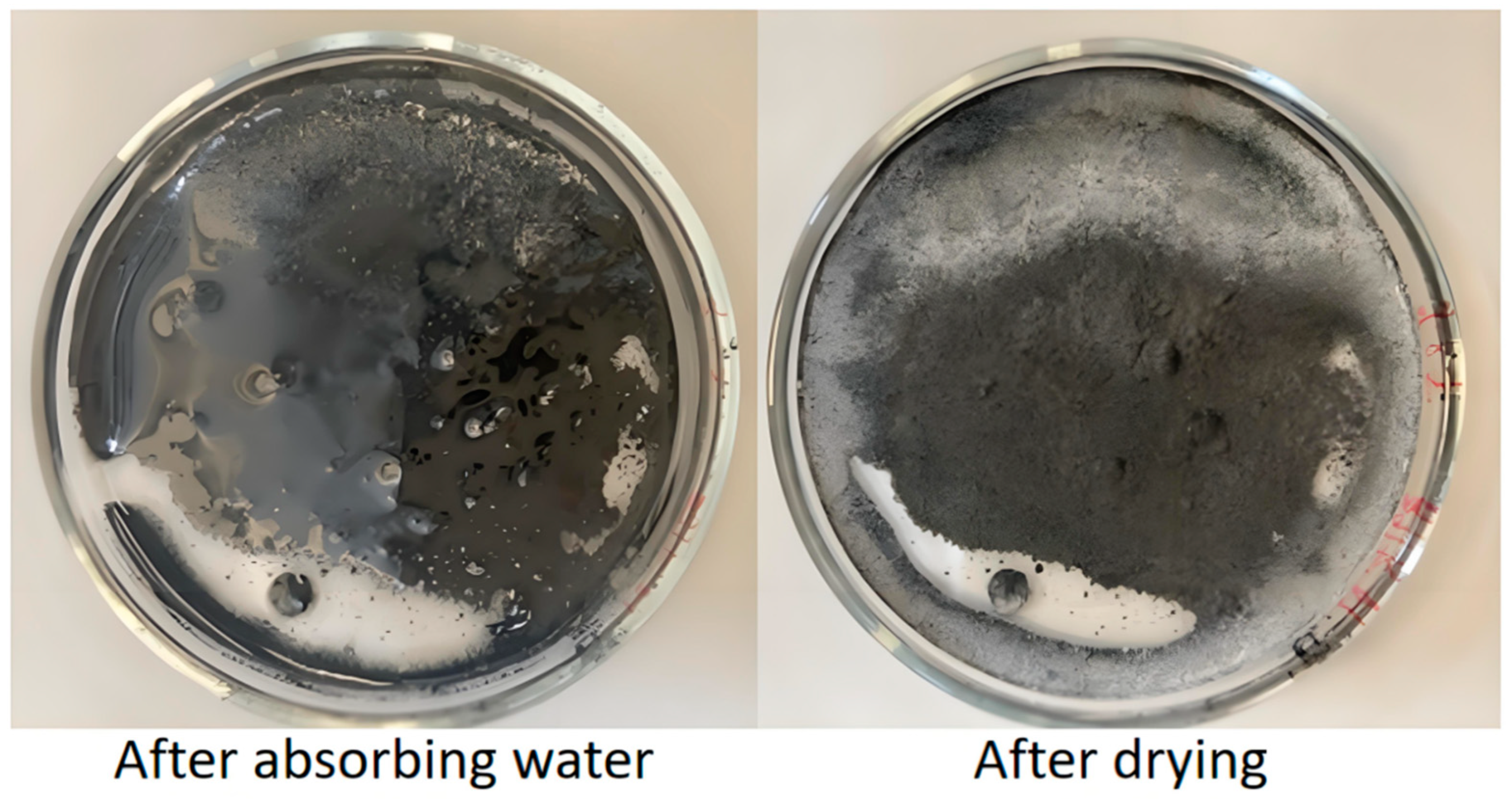

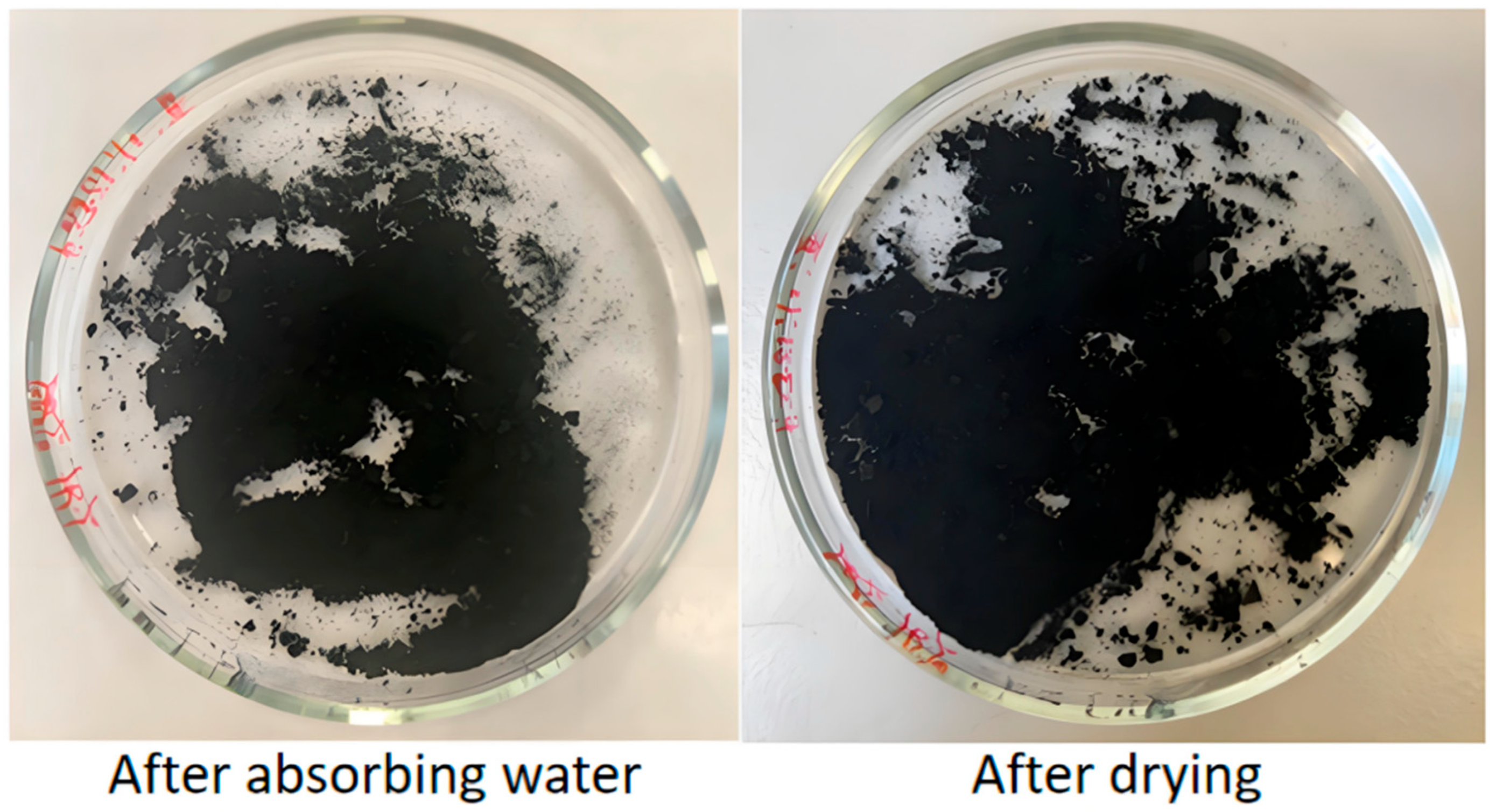

3.8. Water Sorption Analysis

3.8.1. The Influence of Carbonization Conditions

3.8.2. The Influence of Salt Content

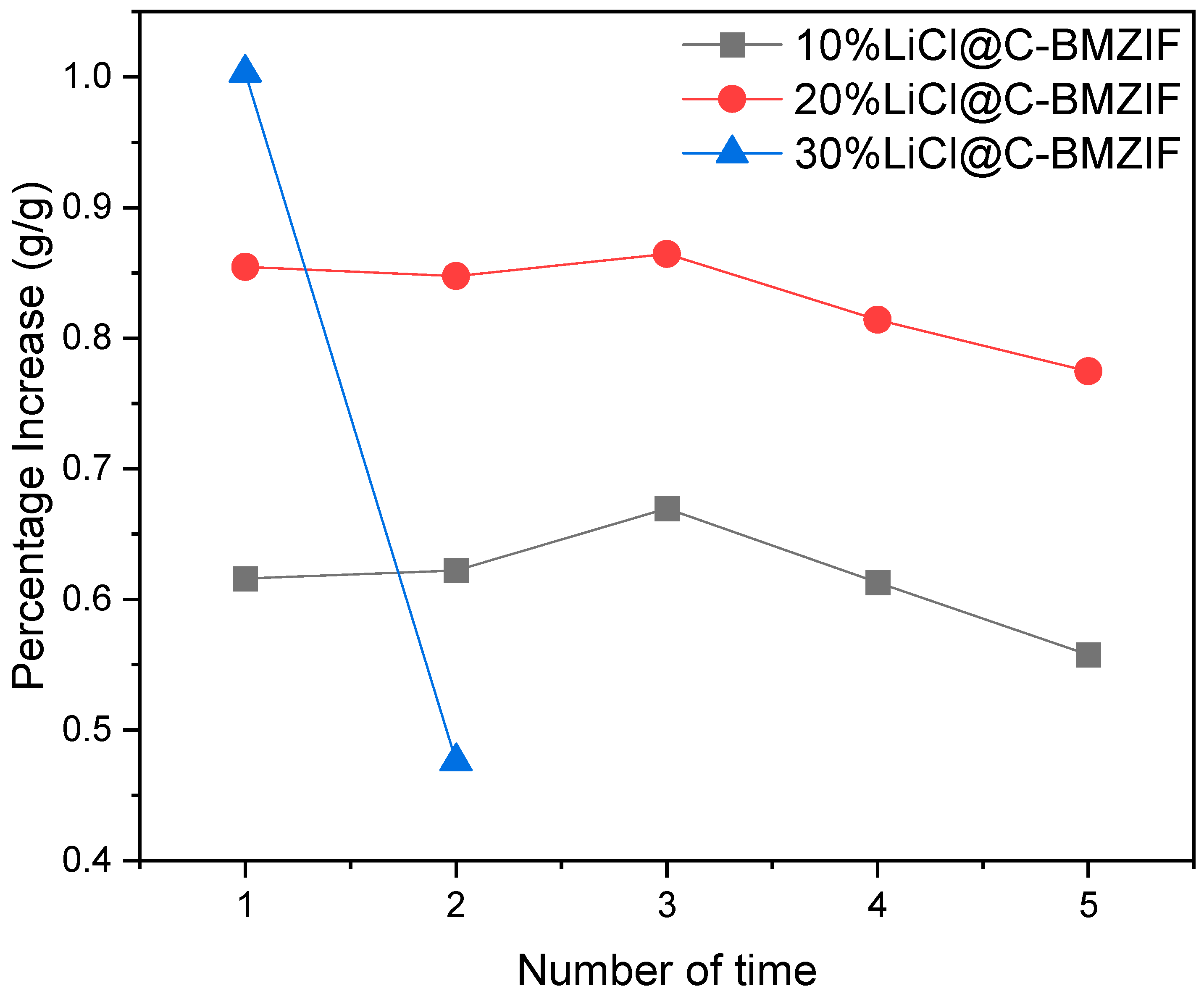

3.8.3. The Influence of Cycle Stability

4. Limitations and Outlook

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Outlook

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Bimetallic Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (BMZIFs) were successfully synthesized via liquid-phase precipitation, employing salts Co(NO3)2·6H2O and Zn(NO3)2·6H2O in conjunction with the organic linker 2-methylimidazole. The resulting BMZIF exhibited a rhombic dodecahedron structure with an average size of ~90 nm, and the ratio of Zn2+ to Co2+ was approximately 69:1. LiCl was subsequently incorporated by the impregnation method, yielding the composite material.

- (2)

- Carbonization at 1000 °C produced C-BMZIF (1000C-BMZIF), which exhibited the most pronounced reactivity with water among the tested samples. Consequently, it demonstrated the optimal thermal energy storage performance, with a final weight loss of ~19.7% due to dehydration and a measured water adsorption capacity of 0.24 g·g−1.

- (3)

- Based on the present results, the composite material with a 20 wt% LiCl loading (20%LiCl@C-BMZIF) showed the highest thermal storage capacity, with a final weight loss of 53.6%. Moreover, it retained structural stability and exhibited excellent water adsorption performance, achieving a capacity of 0.84 g·g−1 and an adsorption rate of 0.01 s−1.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| BJH | Barrett–Joyner–Halenda |

| BMZIF | Bimetallic Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (Specifically Refers to Zn2+ and Co2+) |

| C-BMZIF | Carbonized BMZIF |

| 600C-BMZIF | BMZIF after Carbonization up to 600 °C |

| 800C-BMZIF | BMZIF after Carbonization up to 800 °C |

| 1000C-BMZIF | BMZIF after Carbonization up to 1000 °C |

| CAS | Chemical Abstracts Service |

| C=C | Carbon-Carbon double bond |

| C≡C | Carbon-Carbon triple bond |

| C-H | Carbon-Hydrogen bond |

| C-N | Carbon-Nitrogen bond |

| C-O | Carbon-Oxygen single bond |

| Co-O | Cobalt-Oxygen bond |

| DES | Deep Eutectic Solvents |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| ICP | Inductively Coupled Plasma |

| LiCl@C-BMZIF | Porous Matrix “In-salt” Composite Material formed by compounding Lithium Chloride into C-BMZIF |

| MOFs | Metal–Organic Frameworks |

| N % LiCl@C-BMZIF | N % mass fraction concentration of Porous Matrix “In-salt” Composite Material |

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

References

- Milov, V. European gas price crisis: Is Gazprom responsible? Eur. View 2022, 21, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, A.D. Progress and recent trends in wind energy. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2004, 30, 501–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akorede, M.F.; Hizam, H.; Pouresmaeil, E. Distributed energy resources and benefits to the environment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, L.; Gasia, J.; Cabeza, L.F. Thermal energy storage (TES) for industrial waste heat (IWH) recovery: A review. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I. Thermal energy storage systems as a key technology in energy conservation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2002, 26, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, S.; Yu, Z.G.; Qu, H.; Sun, W.; Yang, J.; Suresh, L.; Zhang, X.; Koh, J.J.; Tan, S.C. An Asymmetric Hygroscopic Structure for Moisture-Driven Hygro-Ionic Electricity Generation and Storage. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2201228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, R. Sorption thermal energy storage: Concept, process, applications and perspectives. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 27, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, G.; Lin, Y.; Fang, G. An overview of thermal energy storage systems. Energy 2018, 144, 341–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Lin, K.; Zhang, Q.; Di, H. Application of latent heat thermal energy storage in buildings: State-of-the-art and outlook. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 2197–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, C.; Cooper, P.; Fernández, A.I.; Cabeza, L.F. Review of technology: Thermochemical energy storage for concentrated solar power plants. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 909–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Lin, J.; Huang, H.; Wu, Q.; Shen, Y.; Xiao, Y. Optimization of thermochemical energy storage systems based on hydrated salts: A review. Energy Build. 2021, 244, 111035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlia, T.M.I.; Saktisahdan, T.J.; Jannifar, A.; Hasan, M.H.; Matseelar, H.S.C. A review of available methods and development on energy storage; technology update. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 33, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbari-Hichri, A.; Bennici, S.; Auroux, A. Enhancing the heat storage density of silica–alumina by addition of hygroscopic salts (CaCl2, Ba (OH)2, and LiNO3). Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2015, 140, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.J. Salt Hydrates for Thermochemical Energy Storage. Ph.D. Dissertation, ResearchSpace@Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbu, I.; Sebarchievici, C. A comprehensive review of thermal energy storage. Sustainability 2018, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Gao, Z.; Lin, N. Self-assembly of metal–organic coordination structures on surfaces. Prog. Surf. Sci. 2016, 91, 101–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, U. Cluster-based inorganic–organic hybrid materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Ren, L.; Xu, X.; Du, Y.; Dou, S.X. Recent development of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) derived porous carbon based materials as electrocatalysts. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1801257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.C.; Bennett, T.D.; Cheetham, A.K. Chemical structure, network topology, and porosity effects on the mechanical properties of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9938–9943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswal, B.P.; Panda, T.; Banerjee, R. Solution mediated phase transformation (RHO to SOD) in porous Co-imidazolate based zeolitic frameworks with high water stability. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 11868–11870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.H.; Fow, K.L.; Chen, G.Z. Synthesis and applications of MOF-derived porous nanostructures. Green Energy Environ. 2017, 2, 218–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, V.F.; Malek, N.I.; Kailasa, S.K. Review on Metal–Organic Framework Classification, Synthetic Approaches, and Influencing Factors: Applications in Energy, Drug Delivery, and Wastewater Treatment. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 44507–44531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, A.N.H.; Doonan, C.J.; Uribe-Romo, F.J.; Knobler, C.B.; O’keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Synthesis, structure, and carbon dioxide capture properties of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 43, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, J.; Guo, X.; Huang, H.; Yang, Q.; Liu, D.; Zhong, C. Recovery of acetone from aqueous solution by ZIF-7/PDMS mixed matrix membranes. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 28394–28400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakzeski, J.; Dębczak, A.; Bruijnincx, P.C.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Catalytic oxidation of aromatic oxygenates by the heterogeneous catalyst Co-ZIF-9. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2011, 394, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhanya, N.; Oboirien, B.; Ren, J.; Musyoka, N.; Sciacovelli, A. Recent advances on thermal energy storage using metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). J. Energy Storage 2021, 34, 102179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Huang, H.; Deng, L. Development of covalent-organic frameworks derived hierarchical porous hollow carbon spheres based LiOH composites for thermochemical heat storage. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 73, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Spieß, A.; Jansen, C.; Nuhnen, A.; Gökpinar, S.; Wiedey, R.; Ernst, S.J.; Janiak, C. Tunable LiCl@ UiO-66 composites for water sorption-based heat transformation applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 13364–13375. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Gao, H.; Tang, Z.; Wang, G. Metal-organic framework-based phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2020, 1, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Shalini, S.; Ahmed, A.; Vaid, T.P.; Kim, K.; Matzger, A.J.; Siegel, D.J. Calculation and Measurement of Salt Loading in Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 16090–16099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Yan, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.C.; Jiang, H.L. Metal–Organic framework-based hierarchically porous materials: Synthesis and applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12278–12326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, H.; Zhang, J. Hygroscopic salt-modulated UiO-66: Synthesis and its open adsorption performance. J. Solid State Chem. 2021, 301, 122304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, E.V.; Karunaweera, C.; Musselman, I.H.; Balkus, K.J., Jr.; Ferraris, J.P. Origins and evolution of inorganic-based and MOF-based mixed-matrix membranes for gas separations. Processes 2016, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Zhai, F.; Su, H.; Sridhar, D.; Algadi, H.; Bin Xu, B.; Pashameah, R.A.; Alzahrani, E.; Abo-Dief, H.M.; Ma, Y.; et al. Progress of metal organic frameworks-based composites in electromagnetic wave absorption. Mater. Today Phys. 2023, 30, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Wang, N.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y. Towards High-Performance Zinc-Based Hybrid Supercapacitors via Macropores-Based Charge Storage in Organic Electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 9610–9617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Khan, U.A.; Iqbal, N.; Noor, T. Zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF)-derived porous carbon materials for supercapacitors: An overview. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 43733–43750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Hu, X.; Fang, Z.; Sun, L.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, S.; Hong, W.; Chen, X.; Yu, D. Bifunctional MOF-derived carbon photonic crystal architectures for advanced Zn–air and Li–S batteries: Highly exposed graphitic nitrogen matters. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1701971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaldivar, R.; Nokes, J.; Steckel, G.; Kim, H.; Morgan, B. The effect of atmospheric plasma treatment on the chemistry, morphology and resultant bonding behavior of a pan-based carbon fiber-reinforced epoxy composite. J. Compos. Mater. 2010, 44, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gour, S. Manufacturing Nano-Sized Powders Using Salt-and Sugar-Assisted Milling. Ph.D. Dissertation, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fassel, V.A. Quantitative Elemental Analyses by Plasma Emission Spectroscopy: Atomic spectra excited in inductively coupled plasmas are used for simultaneous multielement analyses. Science 1978, 202, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.J.; Liu, Y.F.; Zhang, W.F.; Zhang, C.; Chai, G.B.; Zhang, Q.D.; Mao, J.; Ahmad, I.; Zhang, S.S.; Xie, J.P. Encapsulation and controlled release of fragrances from MIL-101 (Fe)-based recyclable magnetic nanoporous carbon. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 640, 128453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime, R.B.; Bair, H.E.; Vyazovkin, S.; Gallagher, P.K.; Riga, A. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA). In Thermal Analysis of Polymers: Fundamentals and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 241–317. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Shioyama, H.; Akita, T.; Xu, Q. Metal–Organic framework as a template for porous carbon synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 5390–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanta, S.R.; Muralidharan, K. Solution phase chemical synthesis of nano aluminium particles stabilized in poly(vinylpyrrolidone) and poly(methylmethacrylate) matrices. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruk, M.; Antochshuk, V.; Jaroniec, M.; Sayari, A. New approach to evaluate pore size distributions and surface areas for hydrophobic mesoporous solids. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 10670–10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagiello, J.; Thommes, M. Comparison of DFT characterization methods based on N2, Ar, CO2, and H2 adsorption applied to carbons with various pore size distributions. Carbon 2004, 42, 1227–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemicals | Manufacturer | CAS | Purity/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Methylimidazole | Acros | 693-98-1 | 99% |

| Methanol | Acros | 67-56-1 | 98% |

| Cobalt(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O) | Acros | 10026-22-9 | 98% |

| Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O) | Acros | 10196-18-6 | 98% |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Sigma | 9003-39-8 | 98% |

| Element | Concentration/mg·L−1 | Molar Mass/g·mol−1 | Amount of Substance/mol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zn | 0.76 | 65.38 | 0.0116 |

| Co | 0.01 | 58.93 | 1.70 × 10−4 |

| BMZIF | C-BMZIF | LiCl@C-BMZIF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface area with MBET/m2·g−1 | 1945.82 | 1044.74 | 162.83 |

| Pore volume with DFT/cm3·g−1 | 1.21 | 1.29 | 0.35 |

| Sample | 1000C-BMZIF | 5%LiCl@C-BMZIF | 10%LiCl@C-BMZIF | 20%LiCl@C-BMZIF | 30%LiCl@C-BMZIF | LiCl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dehydration final weight/% | 80.30 | 68.30 | 60.35 | 46.44 | 49.42 | 44.53 |

| Final weight for water lost/% | 19.70 | 31.70 | 39.65 | 53.56 | 50.58 | 55.47 |

| 600C-BMZIF | 800C-BMZIF | 1000C-BMZIF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Water Adsorption Capacity /g·g−1 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.24 |

| Calculated Water Adsorption Capacity a/g·g−1 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| Calculated Rate of Water Adsorption b/s−1 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| R2 | 0.996 | 0.999 | 0.997 |

| 5% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 50% | LiCl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Water Adsorption Capacity/g·g−1 | 0.36 | 0.66 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.85 |

| Calculated Water Adsorption Capacity a/g·g−1 | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.98 | 1.84 | 1.05 | 4.10 |

| Calculated Rate of Water Adsorption b/s−1 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| R2 | 0.99978 | 0.99976 | 0.99968 | 0.99661 | 0.99969 | 0.99985 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, F.; Wei, W.; Fang, Q.; Fan, X. LiCl@C-BMZIF Porous Composites: Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and the Effects of Carbonization Temperature and Salt Loading on Thermochemical Energy Storage. Crystals 2025, 15, 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100889

Zhang F, Wei W, Fang Q, Fan X. LiCl@C-BMZIF Porous Composites: Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and the Effects of Carbonization Temperature and Salt Loading on Thermochemical Energy Storage. Crystals. 2025; 15(10):889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100889

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Fuyao, Wenjing Wei, Quanrong Fang, and Xianfeng Fan. 2025. "LiCl@C-BMZIF Porous Composites: Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and the Effects of Carbonization Temperature and Salt Loading on Thermochemical Energy Storage" Crystals 15, no. 10: 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100889

APA StyleZhang, F., Wei, W., Fang, Q., & Fan, X. (2025). LiCl@C-BMZIF Porous Composites: Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and the Effects of Carbonization Temperature and Salt Loading on Thermochemical Energy Storage. Crystals, 15(10), 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100889