Balancing Photocatalytic and Photothermal Elements for Enhanced Solar Evaporation—A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Photothermal Materials: Working Principles and Examples

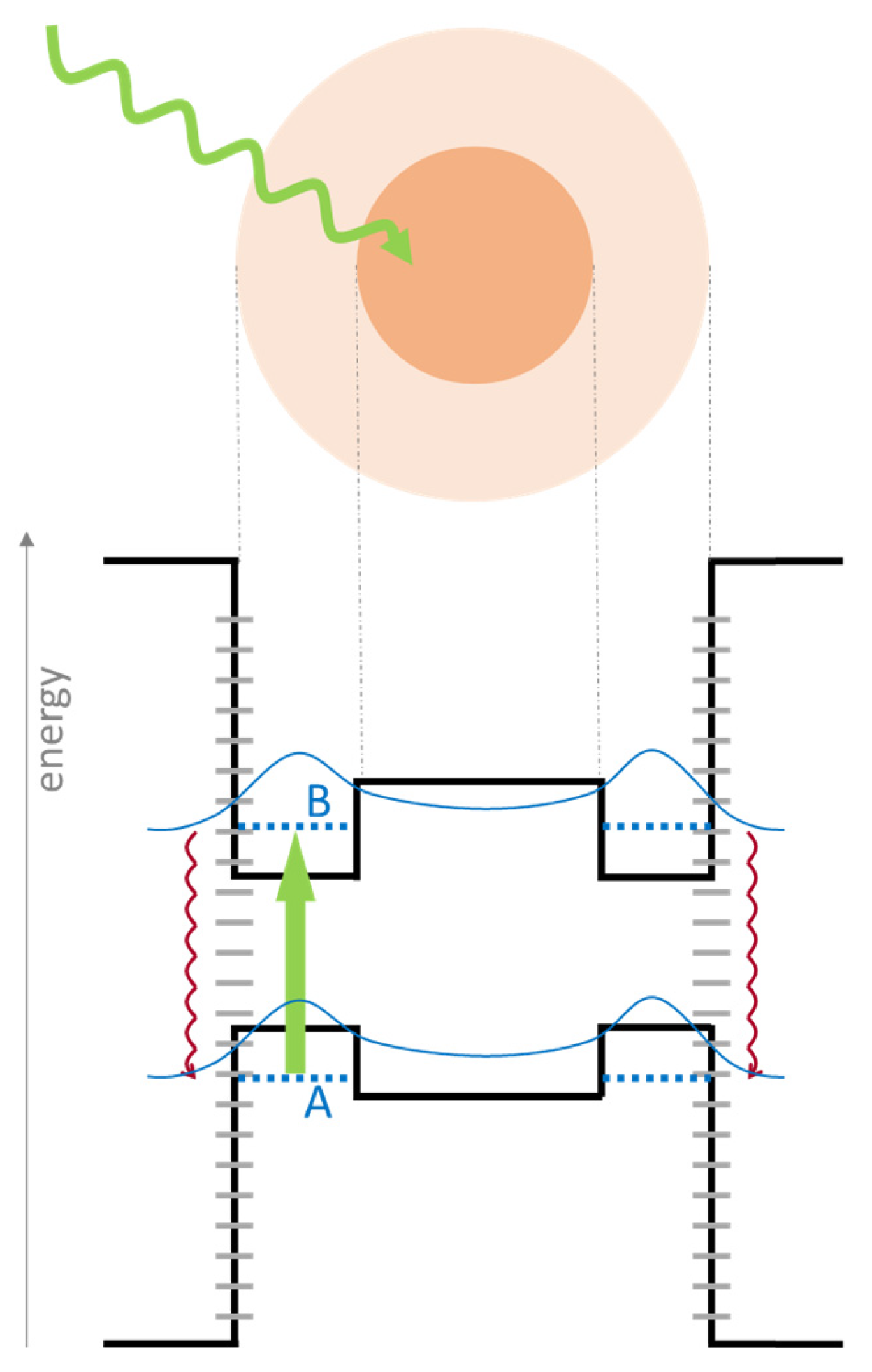

- Light absorption associated with electron excitation: Materials with a broadband absorption spectrum throughout the UV-VIS-NIR range as well as high absorption coefficients are desirable for this stage [29]. However, if a photocatalytic element is to be added, its light absorption properties should be considered, as more extensively discussed in Section 6.

- Energy relaxation via thermalization: Excited electrons rapidly return to lower (ground) energy states. For photothermal applications, materials where such relaxation occurs through non-radiative decay pathways are required [30]. Here, the relaxation energy is transferred to lattice vibrations (phonons), leading to a temperature increase in the material (thermalization).

- Heat localization and transfer: For solar-driven evaporation applications, the heat generated via light absorption and subsequent thermalization must be precisely localized at the water–air interface to maximize evaporation efficiency. Ideal photothermal materials should have an appropriate morphology to achieve this localization, such as a porous or cellular architectures at the micro- and nanoscale, designed to facilitate water transport to the evaporation surface while simultaneously providing thermal insulation to the underlying water body. The objective is to maximize evaporation rates while minimizing the energy lost by heating the bulk water [31,32].

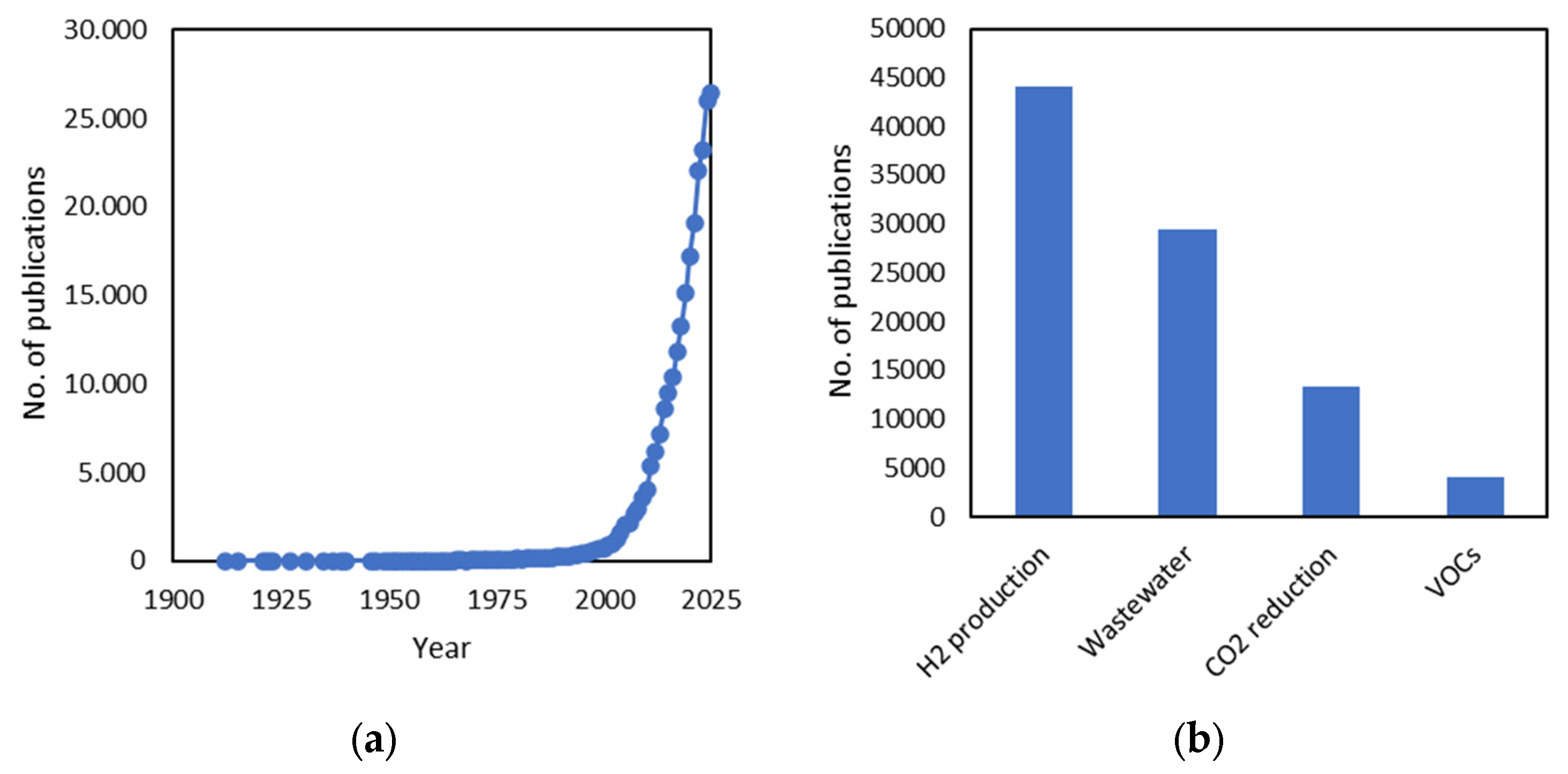

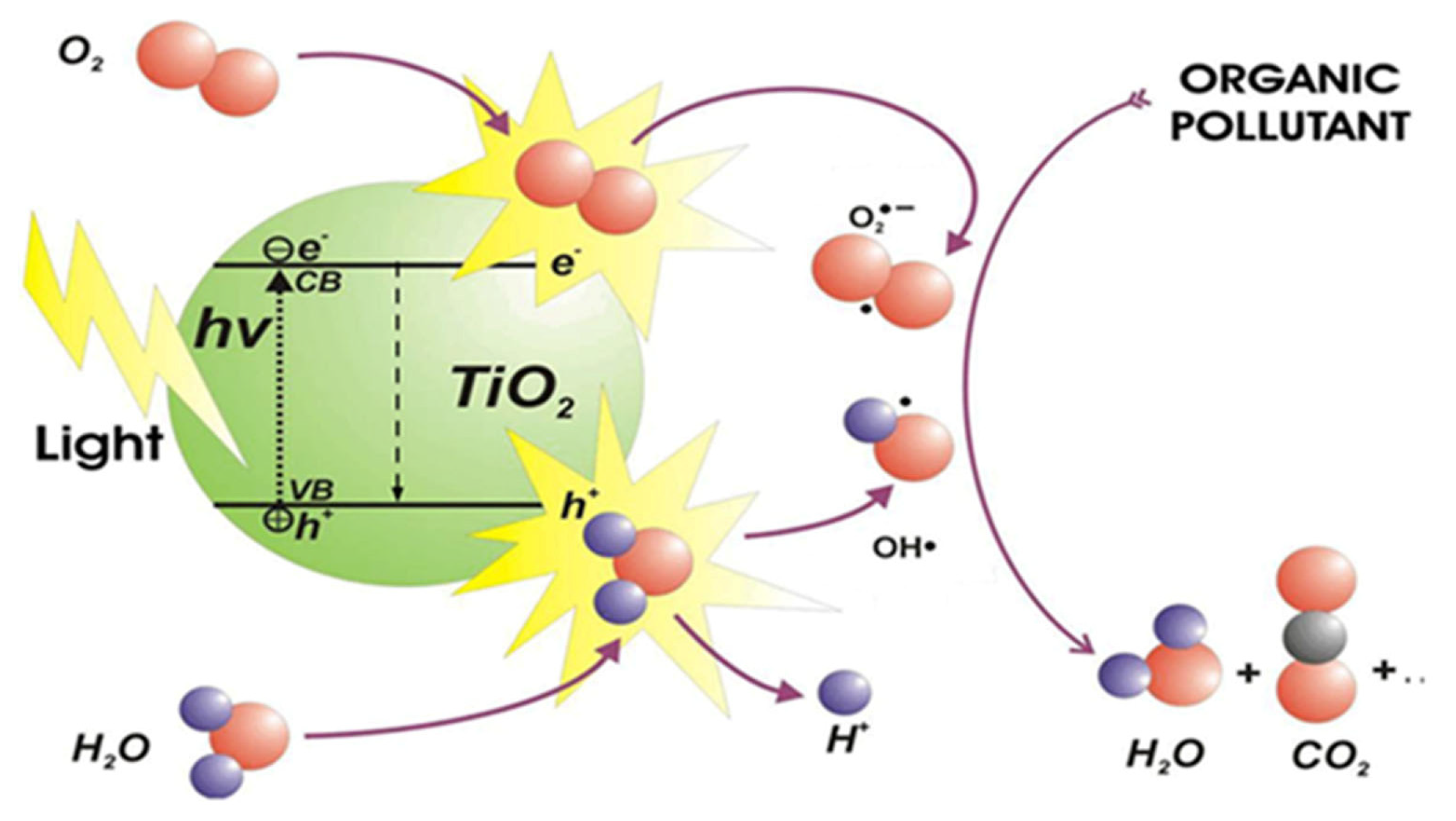

3. Photocatalytic Materials: Working Principles and Examples

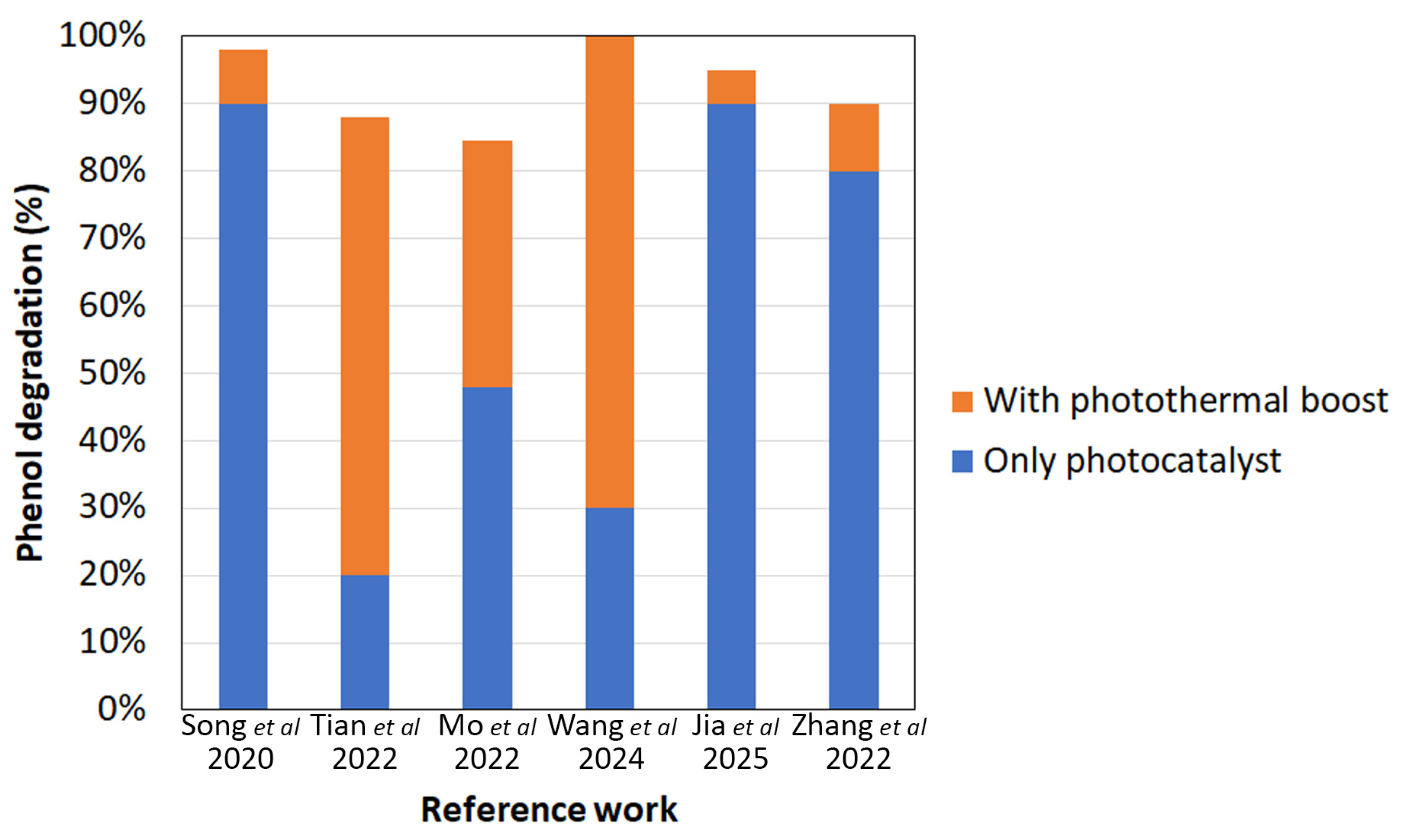

4. Benefits of Coupling Photothermal and Photocatalytic Materials

5. Trends in Literature Studies on Photocatalytic-Photothermal Evaporators

5.1. Materials

5.2. Testing Conditions

5.3. LCA

6. Limitations of Combined Photocatalytic-Photothermal Evaporators

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

- The analysis of the current literature indicates that the combination of photothermal and photocatalytic functionalities is indeed a potential benefit for interfacial solar evaporators. While the photocatalyst is not expected to have a negative impact on the photothermal agent, and vice versa, the added thermal stimulus can support the pollutants degradation action of the photocatalyst thanks to a variety of mechanisms. While the potential synergisms between photocatalysis and thermal catalysis have been investigated in the literature, the interplay between the photocatalyst and the photothermal element in photothermal evaporators has been scarcely explored. The combination of pollutant degradation and rejection by evaporation, the potential occurrence of gas-phase reaction pathways alongside liquid-phase ones, and the possible competition for light absorption between the photocatalyst and the photothermal element all add complexity to the system and require dedicated investigation.

- The analysis of the literature also highlighted a dire need for greater standardization of testing conditions to improve the comparability of results. Moreover, the geometry and materials of the solar still, as well as the testing parameters for photocatalytic and pollutant-rejection experiments, should always be reported. Unfortunately, these aspects are often missing in the literature studies, limiting comparability between different setups.

- Limits to such beneficial interplay mostly come from the materials selection and device configuration, as the choice of where to collocate the two active elements should ensure intimate contact between the two as well as the possibility to effectively convey irradiation at both of their surfaces. In this respect, competition for light absorption should be considered, focusing on strategies to promote charge separation by the formation of Schottky junctions between the photocatalyst and the photothermal material. Along with more commonly employed materials, QDs can represent highly tunable and versatile photothermal materials, allowing them to overcome the risk of light absorption competition.

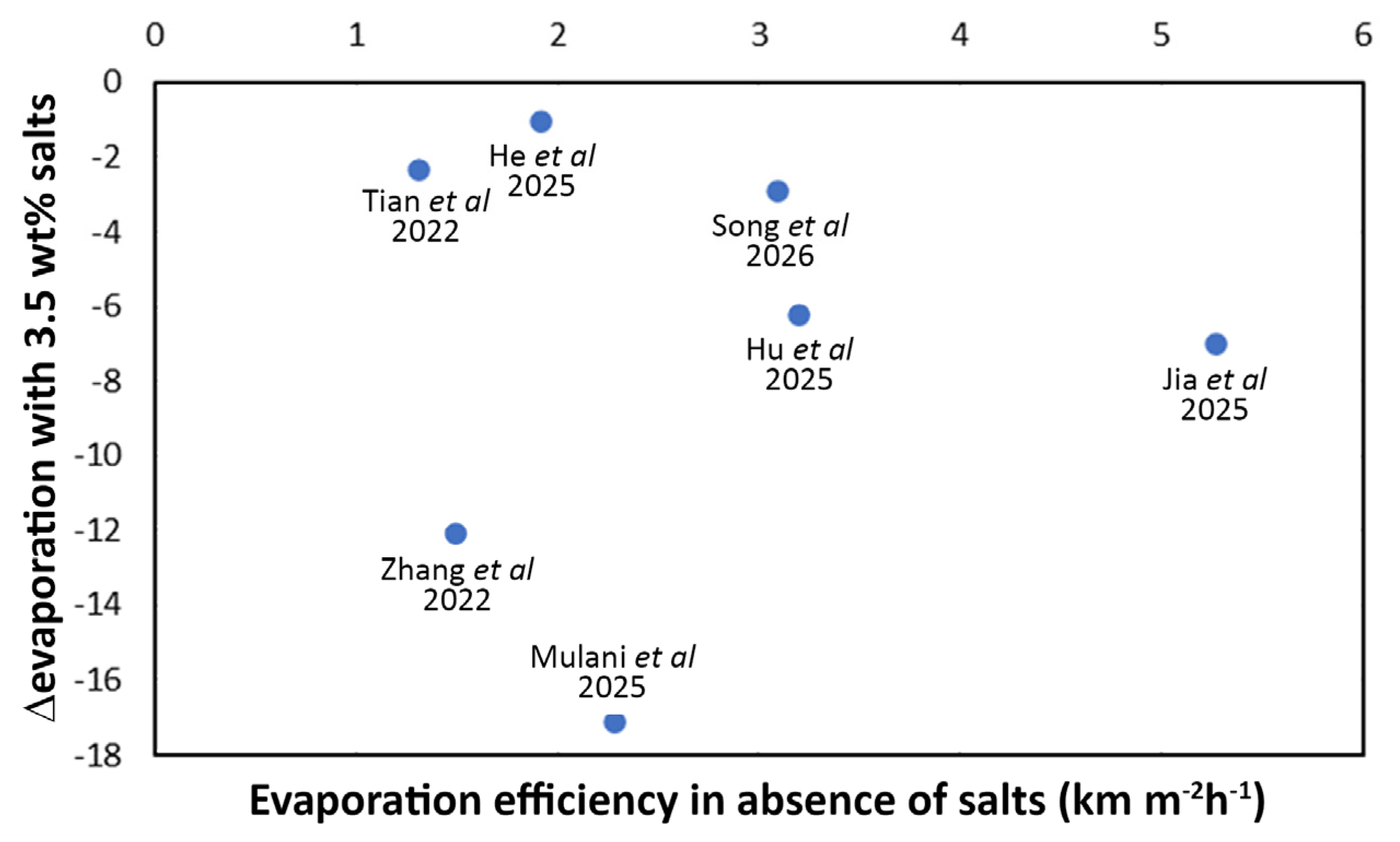

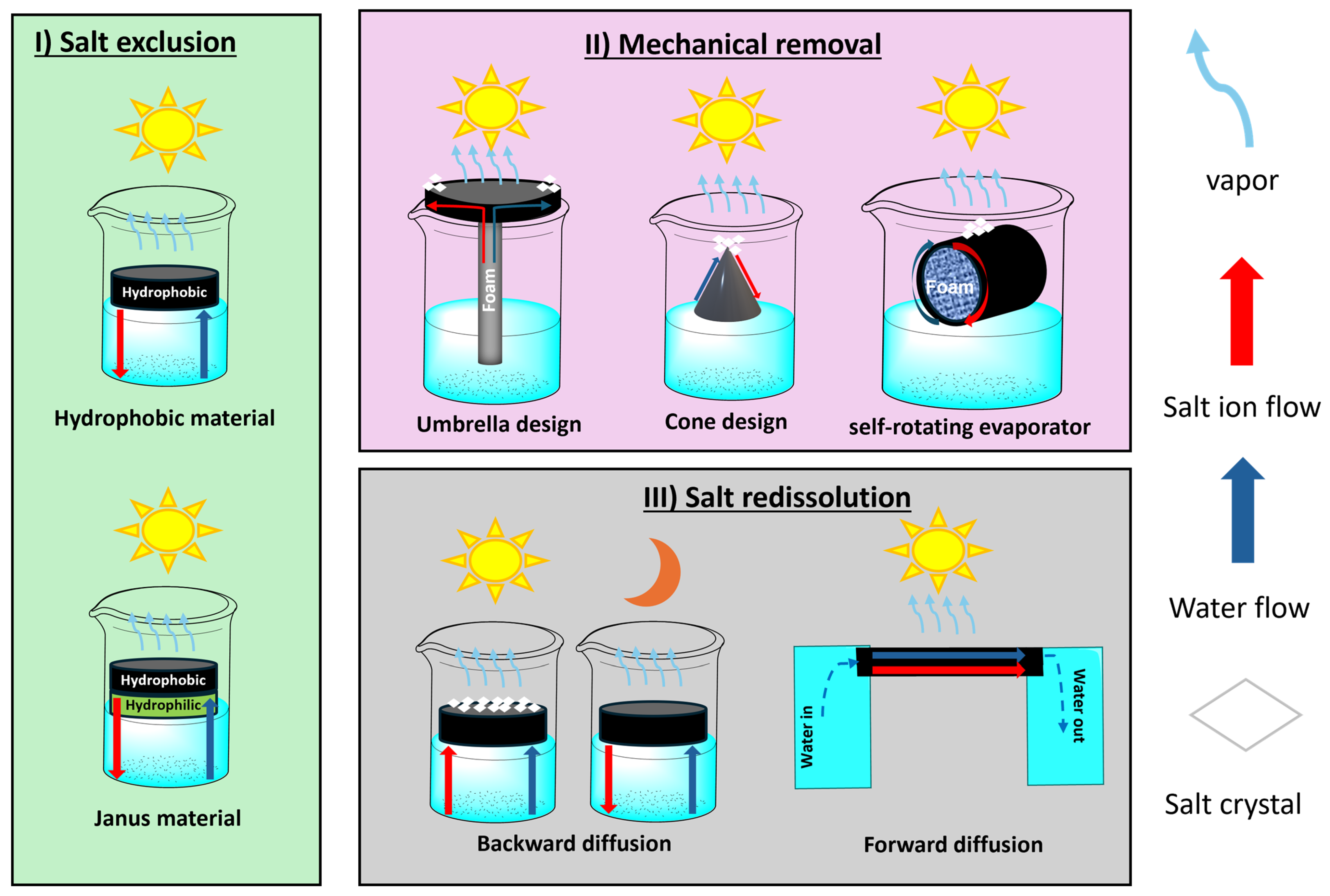

- Even in the presence of high-quality and highly efficient materials, a non-ideal device configuration can still hamper the overall functionality and its duration over time. The contact time between photocatalyst and pollutant should not be too short (depending on the reaction rate) to guarantee that the process is able to degrade the VOCs contained in water, thus contributing to improvement of the condensed water quality. A higher tortuosity of the porous network containing the photoactive elements can promote reaction rates. In this frame, salt management also plays a vital role: on the one hand, it can negatively affect the photocatalytic performance; on the other, an excess of rejected salts accumulating on the device surface will deactivate both photoactive elements, thus reducing the device lifetime significantly. While possible design strategy and materials choice were discussed here as a function of the type of water effluent to be treated, the literature reports on this topic remain scarce, and further research is urgently needed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tao, P.; Ni, G.; Song, C.; Shang, W.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J.; Chen, G.; Deng, T. Solar-Driven Interfacial Evaporation. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yao, D.; Gao, X.; Lu, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, W.; Pang, X. Modified PET Fiber Sponge with Synergistic Photothermal Conversion Function for Efficient Solar Interfacial Evaporation. Desalination 2026, 618, 119502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Sun, C.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Tan, H.; Li, Y. Titanium Suboxide-Heteropoly Blue Self-Assembled Superlattices for Solar Photothermal High-Efficiency Water Evaporation. Desalination 2026, 617, 119415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, J.; Tang, W.; Gao, W.; Li, Y.; Shang, Y. Design of Morphology and Light-Absorbing Tunable FexOy@SiO2@C Nanoparticles for Solar-Driven Water Evaporation and Purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 380, 135449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, H.; Shen, J.; Wen, C.; Luo, L.; Wang, X.; Zheng, R.; Huang, S.; Lin, C.; Sa, B. Self-Assembly Hierarchical MXene/Bacterial Cellulose Composite Films with Accelerated Surface Charge Transfer for Highly Efficient Solar-Driven Water Evaporation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 382, 135886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Shi, R.; Ahmed, I.; Howells, C.T.; Al Huwayz, M.; Alomar, M.; Shakoor, B.; Shah, M.; Arshad, N.; Ha, V.T.H.; et al. Engineering Interfacial Thermal Energy Management via Grooved B4C-Polyurethane Architectures for High-Efficiency Solar-Thermal Desalination. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 382, 135933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.-F.; Liu, W.-X.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Ma, L.; Ding, S.-J.; Wang, Q.-Q. Plasmon-Enhanced Light Absorption and Photothermal Conversion in ReS2/CoS2/Cu2-xS Hollow Nanostructures for Efficient Solar Water Evaporation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2026, 704, 139327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Sun, F.; Yang, L.; Zhou, C.; Liu, C.; Yu, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q. Recent Advanced Optical Adsorption Regulation Strategies in Solar-Driven Evaporation for Efficient Clean Water Production: A Review. Mater. Res. Bull. 2024, 174, 112730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Zhou, W.; Yu, F.; Wang, J.; Xiong, X.; Liu, G.; Xia, Y.; Wang, X. Materials Design and System Structures of Solar Steam Evaporators. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2023, 42, e13944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djellabi, R.; Noureen, L.; Dao, V.-D.; Meroni, D.; Falletta, E.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Bianchi, C.L. Recent Advances and Challenges of Emerging Solar-Driven Steam and the Contribution of Photocatalytic Effect. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 134024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoodi, K.A.; Dhahad, H.A.; Alawee, W.H.; Omara, Z.M.; Yusaf, T. Pyramid Solar Distillers: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Techniques. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, H.; Shuwanto, H.; Astarini, N.A.; Lie, J.; Ginting, R.T.; Tsai, M.-L.; Shih, S.-J.; Sillanpää, M. A Brief Review of Emerging Strategies in Designing Interfacial Solar Steam Generation for Desalination, Water Purification, Power Generation, and Sea Farming. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 2663–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, S.C. Functionalizing Solar-Driven Steam Generation towards Water and Energy Sustainability. Nat. Water 2025, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yin, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Design and Optimization of Solar Steam Generation System for Water Purification and Energy Utilization: A Review. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2019, 58, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, G.W.; Yamauchi, Y.; Hu, L.; Mi, B.; Xu, N.; Zhu, J.; Wang, P. Solar Evaporation and Clean Water. Nat. Water 2025, 3, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Qi, D.; Han, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xu, H.; You, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Wei, Y.; Ma, J. Volatile-Organic-Compound-Intercepting Solar Distillation Enabled by a Photothermal/Photocatalytic Nanofibrous Membrane with Dual-Scale Pores. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 9025–9033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Xu, Y.; Sun, F.; Chen, X.; Wang, W. Perspective for Removing Volatile Organic Compounds during Solar-Driven Water Evaporation toward Water Production. EcoMat 2021, 3, e12147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iervolino, G.; Zammit, I.; Vaiano, V.; Rizzo, L. Limitations and Prospects for Wastewater Treatment by UV and Visible-Light-Active Heterogeneous Photocatalysis: A Critical Review. In Heterogeneous Photocatalysis: Recent Advances; Muñoz-Batista, M.J., Navarrete Muñoz, A., Luque, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 225–264. [Google Scholar]

- Tucci, A.P.; Murgolo, S.; De Ceglie, C.; Mascolo, G.; Carmagnani, M.; Ronco, P.; Bestetti, M.; Franz, S. Photoelectrocatalytic Advanced Oxidation of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Groundwaters of the Veneto Region, Italy. Catal. Today 2025, 450, 115205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Poyatos, L.T.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M.; Morales-Torres, S.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J. Novel Strategies to Develop Efficient Carbon/TiO2 Photocatalysts for the Total Mineralization of VOCs in Air Flows: Improved Synergism between Phases by Mobile N-, O- and S-Functional Groups. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 508, 160986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Wei, J.; Han, Z.; Tian, Q.; Xiao, C.; Hasi, Q.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L. An Integrated Solar Absorber with Salt-Resistant and Oleophobic Based on PVDF Composite Membrane for Solar Steam Generation. Mater. Today Energy 2022, 25, 100959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Liu, Z.; Tan, S.H.; Low, S.C. Addressing Critical Challenges of Biofouling in Solar Evaporation: Advanced Strategies for Anti-Biofouling Performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 367, 132874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijing, L.D.; Woo, Y.C.; Choi, J.-S.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.-H.; Shon, H.K. Fouling and Its Control in Membrane Distillation—A Review. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 475, 215–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Yadav, S.; Ibrar, I.; Al Juboori, R.A.; Razzak, S.A.; Deka, P.; Subbiah, S.; Shah, S. Fouling and Performance Investigation of Membrane Distillation at Elevated Recoveries for Seawater Desalination and Wastewater Reclamation. Membranes 2022, 12, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, N.; Ivanez, J.; Highfield, J.; Ruppert, A.M. Photo-/Thermal Synergies in Heterogeneous Catalysis: Towards Low-Temperature (Solar-Driven) Processing for Sustainable Energy and Chemicals. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 296, 120320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti, M.V.; Shinnur, M.V.; Pedeferri, M.; Ferrari, A.M.; Rosa, R.; Meroni, D. Toward Sustainable Photocatalysis: Addressing Deactivation and Environmental Impact of Anodized and Sol–Gel Photocatalysts. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, 2401017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimoldi, L.; Meroni, D.; Falletta, E.; Pifferi, V.; Falciola, L.; Cappelletti, G.; Ardizzone, S. Emerging Pollutant Mixture Mineralization by TiO2 Photocatalysts. The Role of the Water Medium. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioja, N.; Zorita, S.; Peñas, F.J. Effect of Water Matrix on Photocatalytic Degradation and General Kinetic Modeling. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 180, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Guo, Y.; Yu, G. Carbon Materials for Solar Water Evaporation and Desalination. Small 2021, 17, 2007176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, V.-D.; Choi, H.-S. Carbon-Based Sunlight Absorbers in Solar-Driven Steam Generation Devices. Glob. Chall. 2018, 2, 1700094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Li, Z.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Shi, K.; Bu, X.; Alshehri, S.M.; Bando, Y.; Yamauchi, Y.; et al. MOF-Derived Nanoarchitectured Carbons in Wood Sponge Enable Solar-Driven Pumping for High-Efficiency Soil Water Extraction. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Asakura, Y.; Eguchi, M.; Xu, X.; Yamauchi, Y. Water Activation in Solar-Powered Vapor Generation. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2212100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seh, Z.W.; Liu, S.; Low, M.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Liu, Z.; Mlayah, A.; Han, M.-Y. Janus Au-TiO2 Photocatalysts with Strong Localization of Plasmonic Near-Fields for Efficient Visible-Light Hydrogen Generation. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 2310–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Astruc, D. Nanogold Plasmonic Photocatalysis for Organic Synthesis and Clean Energy Conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 7188–7216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; He, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, B. Bifunctional Au@TiO2 Core–Shell Nanoparticle Films for Clean Water Generation by Photocatalysis and Solar Evaporation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 132, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucchi, M.; Meroni, D.; Safran, G.; Villa, A.; Bianchi, C.L.; Prati, L. Noble Metal Promoted TiO2 from Silver-Waste Valorisation: Synergism between Ag and Au. Catalysts 2022, 12, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marelli, M.; Evangelisti, C.; Diamanti, M.V.; Dal Santo, V.; Pedeferri, M.P.; Bianchi, C.L.; Schiavi, L.; Strini, A. TiO2 Nanotubes Arrays Loaded with Ligand-Free Au Nanoparticles: Enhancement in Photocatalytic Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 31051–31058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirjani, A.; Amlashi, N.B.; Ahmadiani, Z.S. Plasmon-Enhanced Photocatalysis Based on Plasmonic Nanoparticles for Energy and Environmental Solutions: A Review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 9085–9123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeksha, B.; Sadanand, V.; Hariram, N.; Rajulu, A.V. Preparation and Properties of Cellulose Nanocomposite Fabrics with in Situ Generated Silver Nanoparticles by Bioreduction Method. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2021, 6, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage McEvoy, J.; Zhang, Z. Antimicrobial and Photocatalytic Disinfection Mechanisms in Silver-Modified Photocatalysts under Dark and Light Conditions. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2014, 19, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Xu, L.; Sun, M.; Pan, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhao, Y. Fabrication, Photocatalysis and Desalination Properties of 3D MOF/PVDF/MF Evaporator Based on Ag-MOFs. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Tian, X.; Wang, Z.; Cao, R.; Ma, P.; Ma, S.; Lu, X. Heterogeneous Structure Based on MXene-TiO2-Ag with Biomass Hydrogel for Solar Desalination and Photocatalytic Removal of VOCs. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 523, 168554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Jin, X.; Niu, X.; Guo, T.; Zeng, X.; Long, J.; Cheng, G. Enhanced Photothermal Catalytic NO + CO Reaction via Cu/Ce-TiO2 with Oxygen Vacancies. Mol. Catal. 2026, 588, 115554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hou, J.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wan, Y.; Lu, T.; Ding, W. Rational Construction of “All-in-One” Vertically Aligned Copper Single-Atomic Graphene Oxide Based Evaporators for Integrated Solar Steam Generation and Sulfate Radical-Advanced Oxidation Process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 368, 132960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wong, K.H.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, M. Copper-Doped PDA Nanoparticles with Self-Enhanced ROS Generation for Boosting Photothermal/Chemodynamic Combination Therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2025, 13, 3903–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.; Seo, D.H.; McDonagh, A.M.; Shon, H.K.; Tijing, L. Semiconductor Photothermal Materials Enabling Efficient Solar Steam Generation toward Desalination and Wastewater Treatment. Desalination 2021, 500, 114853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, S.; Yin, K.; Chang, X.; Lei, Y.; Fan, R.; Dong, L.; Yin, Y.; Chen, X. CuS Nanoflowers/Semipermeable Collodion Membrane Composite for High-Efficiency Solar Vapor Generation. Mater. Today Energy 2018, 9, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Pan, H.; Lou, Y.; Qiu, X.; Zhu, J.; Burda, C. Plasmonic Cu2-xS Nanocrystals: Optical and Structural Properties of Copper-Deficient Copper(I) Sulfides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4253–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, C.; Ibáñez, M.; Dobrozhan, O.; Singh, A.; Cabot, A.; Ryan, K.M. Compound Copper Chalcogenide Nanocrystals. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 5865–6109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifikar, F.; Habibi-Yangjeh, A.; Jahed-Jaafargolikhanlo, M. A Critical Review on Emerging Photothermal-Photocatalytic Materials Composed of g-C3N4 for Energy Production and Environmental Remediation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanderi, D.; Lakhani, P.; Modi, C.K. Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4) as an Emerging Photocatalyst for Sustainable Environmental Applications: A Comprehensive Review. RSC Sustain. 2024, 2, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rosa Cunha, G.; Guaglianoni, W.C.; Bergmann, C.P. CNT/TiO2 Hybrid Nanostructured Materials: Synthesis, Properties and Applications. In Environmental Applications of Nanomaterials; Kopp Alves, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan, B.K.; Dimitrijevic, N.M.; Finkelstein-Shapiro, D.; Wu, J.; Gray, K.A. Coupling Titania Nanotubes and Carbon Nanotubes to Create Photocatalytic Nanocomposites. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, W.; Xiao, H.; Kong, X.-Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Niu, B.; Qian, Y.; Teng, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wen, L. Biomimetic Nacre-Like Silk-Crosslinked Membranes for Osmotic Energy Harvesting. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 9701–9710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Dong, X.; Qi, H.; Tao, R.; Zhang, P. Carbon Quantum Dots with High Photothermal Conversion Efficiency and Their Application in Photothermal Modulated Reversible Deformation of Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Hydrogel. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 3395–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.; Guo, C.; Qian, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, K.; Xue, H.; Tian, J. Self-Assembly of Graphene Quantum Dots into High-Aspect-Ratio Carbon Fibers for Effective Solar Water Desalination. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 371, 133378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slejko, E.A.; Sayevich, V.; Cai, B.; Gaponik, N.; Lughi, V.; Lesnyak, V.; Eychmu, A. Precise Engineering of Nanocrystal Shells via Colloidal Atomic Layer Deposition. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 8111–8118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, L.; Kozak, J. Zur Kenntnis Der Photokatalyse. I. Die Lichtreaktion in Gemischen: Uransalz + Oxalsäure. Z. Elektrochem. Angew. Phys. Chem. 1911, 17, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibner, A. Action of Light on Pigments. Chemiker-Zeitung 1911, 35, 753–755. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, K.; Irie, H.; Fujishima, A. TiO2 Photocatalysis: A Historical Overview and Future Prospects. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 44, 8269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, C.; Robert, D. Fifty Years of Research in Environmental Photocatalysis: Scientific Advances, Discoveries, and New Perspectives. Catalysts 2024, 14, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordello, F.; Calza, P.; Minero, C.; Malato, S.; Minella, M. More than One Century of History for Photocatalysis, from Past, Present and Future Perspectives. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodeve, C.F.; Kitchener, J.A. Photosensitisation by Titanium Dioxide. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1938, 34, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrino, F.; D’Arienzo, M.; Mostoni, S.; Dirè, S.; Ceccato, R.; Bellardita, M.; Palmisano, L. Electron and Energy Transfer Mechanisms: The Double Nature of TiO2 Heterogeneous Photocatalysis. Top. Curr. Chem. 2021, 380, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carp, O.; Huisman, C.L.; Reller, A. Photoinduced Reactivity of Titanium Dioxide. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2004, 32, 33–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, A.; Roy, S. A Review of Photocatalysis, Basic Principles, Processes, and Materials. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2024, 8, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augugliaro, V.; Bellardita, M.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, G.; Palmisano, L.; Yurdakal, S. Overview on Oxidation Mechanisms of Organic Compounds by TiO2 in Heterogeneous Photocatalysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2012, 13, 224–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, D. Photocatalysis: Basic Principles, Diverse Forms of Implementations and Emerging Scientific Opportunities. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Le Hunte, S. An Overview of Semiconductor Photocatalysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 1997, 108, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafi, A.; Aji, D.; Khan, M.M. Recent Advances in Photocatalysis: From Laboratory to Market. Results Chem. 2025, 18, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti, M.V.; Pedeferri, M. Concrete, Mortar and Plaster Using Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: Applications in Pollution Control, Self-Cleaning and Photo Sterilization. In Nanotechnology in Eco-Efficient Construction; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 299–326. [Google Scholar]

- Jenima, J.; Priya Dharshini, M.; Ajin, M.L.; Jebeen Moses, J.; Retnam, K.P.; Arunachalam, K.P.; Avudaiappan, S.; Arrue Munoz, R.F. A Comprehensive Review of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Cementitious Composites. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, A.J.; Goswami, A.D.; Trivedi, D.H.; Chavan, P.V.; Jadhav, N.L.; Pinjari, D.V. A Comprehensive Review on Pure and Doped Titanium Oxide Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 181, 115206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.M.; Tripathi, M. A Review of TiO2 Nanoparticles. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2011, 56, 1639–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, F.; Assadi, A.A.; Nguyen-Tri, P.; Ali, I.; Rtimi, S. Titanium-Based Photocatalytic Coatings for Bacterial Disinfection: The Shift from Suspended Powders to Catalytic Interfaces. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 32, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregón, S.; Rodríguez-González, V. Photocatalytic TiO2 Thin Films and Coatings Prepared by Sol–Gel Processing: A Brief Review. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2022, 102, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulus, D.A.S.; Permana, M.D.; Deawati, Y.; Eddy, D.R. A Current Review of TiO2 Thin Films: Synthesis and Modification Effect to the Mechanism and Photocatalytic Activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2025, 27, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chiam, S.L.; Leo, C.P.; Hu, Z. Recent Advances in Photocatalytic TiO2-Based Membranes for Eliminating Water Pollutants. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covaliu-Mierlă, C.I.; Matei, E.; Stoian, O.; Covaliu, L.; Constandache, A.-C.; Iovu, H.; Paraschiv, G. TiO2–Based Nanofibrous Membranes for Environmental Protection. Membranes 2022, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaniawska-Białas, E.; Brudzisz, A.; Nasir, A.; Wierzbicka, E. Recent Advances in Preparation, Modification, and Application of Free-Standing and Flow-Through Anodic TiO2 Nanotube Membranes. Molecules 2024, 29, 5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, M.; Orsi, D.; Cristofolini, L. Tailoring Solid Foam Structures for High-Efficiency Photocatalytic Filtration of Air and Water. Mater. Des. 2025, 260, 114980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isley, S.L.; Penn, R.L. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: Effect of Sol-Gel pH on Phase Composition, Particle Size, and Particle Growth Mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 4469–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-W.; Hou, Y.; Madhan, K.; Senthilkumar, K.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, W.-J. Sol-Gel Nano TiO2 Synthesis Using TTIP: Latest Trends, a Comprehensive Review of Attribute Optimization and Various Applications. Mater. Today 2025, 88, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, D.; Gaishun, V.; Vaskevich, V.; Semchenko, A.; Ruzimuradov, O. TiO2 Sol–Gel Nanomaterials: Synthesis, Properties and Applications. In Titanium Dioxide-Based Multifunctional Hybrid Nanomaterials: Application on Health, Energy and Environment; Prakash, J., Cho, J., Ruzimuradov, O., Fang, D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Rahman, K.H.; Wu, C.-C.; Chen, K.-C. A Review on the Pathways of the Improved Structural Characteristics and Photocatalytic Performance of Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) Thin Films Fabricated by the Magnetron-Sputtering Technique. Catalysts 2020, 10, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahl, A.; Veziroglu, S.; Henkel, B.; Strunskus, T.; Polonskyi, O.; Aktas, O.C.; Faupel, F. Pathways to Tailor Photocatalytic Performance of TiO2 Thin Films Deposited by Reactive Magnetron Sputtering. Materials 2019, 12, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.S.; Sikora, M.S.; Trivinho-Strixino, F.; Praserthdam, S.; Praserthdam, P. A Comprehensive Review of Anodic TiO2 Films as Heterogeneous Catalysts for Photocatalytic and Photoelectrocatalytic Water Disinfection. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykobilov, D.; Thakur, S.; Samiev, A.; Nasimov, A.; Turaev, K.; Nurmanov, S.; Prakash, J.; Ruzimuradov, O. Electrochemical Synthesis and Modification of Novel TiO2 Nanotubes: Chemistry and Role of Key Synthesis Parameters for Photocatalytic Applications in Energy and Environment. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 170, 113419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, D.; Kim, D.; Schmuki, P. TiO2 Nanotubes, Nanochannels and Mesosponge: Self-Organized Formation and Applications. Nano Today 2013, 8, 235–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinnur, M.V.; Pedeferri, M.; Diamanti, M.V. Properties and Photocatalytic Applications of Black TiO2 Produced by Thermal or Plasma Hydrogenation. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 8, 100415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slapničar, Š.; Caf, M.; Kralj, S.; Žerjav, G.; Pintar, A. Revealing the Dual Role of Nanoparticle Size and Surface Ligands in Plasmon-Enhanced Photocatalysis of Au/TiO2 Nanorods. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2026, 720, 165300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selishchev, D.; Lyulyukin, M.; Polskikh, D.; Kovalevskaya, K.; Selishcheva, S.; Cherepanova, S.; Gerasimov, E.; Bukhtiyarov, A.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G. Fe-Decorated Bi2WO6/TiO2-N Heterostructure Photocatalyst for Enhanced Visible Light-Driven Degradation of Organic Micropollutants in Air. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 380, 135146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Poyatos, L.T.; Morales-Torres, S.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J. Sulfur-Doped Carbon/TiO2 Composites for Ethylene Photo-Oxidation. Enhanced Performance by Doping TiO2 Phases with Sulfur by Mobile Species Inserted on the Carbon Support. Catal. Today 2025, 446, 115115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Yu, P.Y.; Mao, S.S. Increasing Solar Absorption for Photocatalysis with Black Hydrogenated Titanium Dioxide Nanocrystals. Science 2011, 331, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanlalhmingmawia, C.; Lee, S.M.; Tiwari, D. Plasmonic Noble Metal Doped Titanium Dioxide Nanocomposites: Newer and Exciting Materials in the Remediation of Water Contaminated with Micropollutants. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 51, 103360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Choudhary, H.; Chauhan, P.; Chaliha, J. Nanomaterials for the Remediation of Microplastics in Wastewater. Nano Trends 2025, 12, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Castillo, A.L.; Hinojosa-Reyes, M.; Camposeco, R.; Hinojosa-Reyes, L. Advances in Bi2O3-Based Photocatalysts: A Review on Synergistic Modifications and Wastewater Treatment Applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2026, 183, 115730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, A.; Siddique, M.; Panchal, S. A Review of Visible-Light-Active Zinc Oxide Photocatalysts for Environmental Application. Catalysts 2025, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiam, S.-L.; Pung, S.-Y.; Yeoh, F.-Y. Recent Developments in MnO2-Based Photocatalysts for Organic Dye Removal: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 5759–5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirkunova, N.; Azaizia, A.; Domarev, S.; Dorogov, M. Nanostructured Copper Oxide Materials for Photocatalysis and Sensors. Eng. Proc. 2025, 118, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zindrou, A.; Belles, L.; Deligiannakis, Y. Cu-Based Materials as Photocatalysts for Solar Light Artificial Photosynthesis: Aspects of Engineering Performance, Stability, Selectivity. Solar 2023, 3, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Si, J.; Cui, Z.; Yuan, Z. Metal-Organic Framework-Based Materials for Solar-Driven Interfacial Evaporation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 502, 158111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Huang, J.; Jiang, H.; Li, H.; Yang, S. Metal–Organic Framework-Based Materials: Emerging High-Efficiency Catalysts for the Heterogeneous Photocatalytic Degradation of Pollutants in Water. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2023, 9, 669–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Messaoudi, N.; Ciğeroğlu, Z.; Şenol, Z.M.; Elhajam, M.; Noureen, L. A Comparative Review of the Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline in Aquatic Environment by G-C3N4-Based Materials. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 55, 104150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, D.R.; Jena, H.M.; Kumar, A.; Baigenzhenov, O.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. Graphene-, GO-, and rGO-Supported Photocatalysts for Degradation of Organic Pollutants: A Comprehensive Review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 40, 104560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondag, S.D.A.; Mazzarella, D.; Noël, T. Scale-Up of Photochemical Reactions: Transitioning from Lab Scale to Industrial Production. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2023, 14, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alalm, M.G.; Djellabi, R.; Meroni, D.; Pirola, C.; Bianchi, C.L.; Boffito, D.C. Toward Scaling-Up Photocatalytic Process for Multiphase Environmental Applications. Catalysts 2021, 11, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samer, M. Biological and Chemical Wastewater Treatment Processes. In Wastewater Treatment Engineering; Samer, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino, V.; Coppola, G.; Calabrò, V.; Chakraborty, S.; Candamano, S.; Algieri, C. Heterogeneous TiO2 Photocatalysis Coupled with Membrane Technology for Persistent Contaminant Degradation: A Critical Review. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayahan, E.; Jacobs, M.; Braeken, L.; Thomassen, L.C.; Kuhn, S.; van Gerven, T.; Leblebici, M.E. Dawn of a New Era in Industrial Photochemistry: The Scale-up of Micro- and Mesostructured Photoreactors. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020, 16, 2484–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buglioni, L.; Raymenants, F.; Slattery, A.; Zondag, S.D.A.; Noël, T. Technological Innovations in Photochemistry for Organic Synthesis: Flow Chemistry, High-Throughput Experimentation, Scale-up, and Photoelectrochemistry. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2752–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Pintossi, D.; Nuño, M.; Noël, T. Membrane-Based TBADT Recovery as a Strategy to Increase the Sustainability of Continuous-Flow Photocatalytic HAT Transformations. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, A.; Otter, P.; Röher, D.; Bhatnagar, A.; Khalil, N.; Gupta, A.K.; Bresciani, R.; Arias, C.A. Combination of Advanced Biological Systems and Photocatalysis for the Treatment of Real Hospital Wastewater Spiked with Carbamazepine: A Pilot-Scale Study. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, M.; Joshi, N.; Verma, A. Scaled-Up Sustainable Wastewater Treatment of Tertiary Effluent for the Removal of Chromophores Using Dual Advanced Oxidation Processes. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2025, 35, e70204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, A. A Scalable IoT-Controlled Photocatalytic System for Pharmaceutical Removal in Real Wastewater Treatment Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 518, 164709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, I.-W.; Huang, F. Toward Large-Scale Water Treatment Using Nanomaterials. Nano Today 2019, 27, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioulas, S.; Rapti, I.; Kosma, C.; Konstantinou, I.; Albanis, T. Photocatalytic Degradation of the Antidepressant Drug Paroxetine Using TiO2 P-25 under Lab and Pilot Scales in Aqueous Substrates. Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplast. 2025, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Rojas, J.; Rao, M.A.; Berruti, I.; Mora, M.L.; Garrido-Ramírez, E.; Polo-López, M.I. Assessment of Solar Photocatalytic Wastewater Disinfection and Microcontaminants Removal by Modified-Allophane Nanoclays Based on TiO2, Fe and ZnO at Laboratory and Pilot Scale. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 157894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapti, I.; Kosma, C.; Albanis, T.; Konstantinou, I. Solar Photocatalytic Degradation of Inherent Pharmaceutical Residues in Real Hospital WWTP Effluents Using Titanium Dioxide on a CPC Pilot Scale Reactor. Catal. Today 2023, 423, 113884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Everitt, H.O.; Liu, J. Synergy between Thermal and Nonthermal Effects in Plasmonic Photocatalysis. Nano Res. 2020, 13, 1268–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhao, B.; Chen, F.; Liu, C.; Lu, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, B. Thermally-Assisted Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction to Fuels. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 408, 127280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Dong, F.; Zhang, Z.; Han, L.; Luo, X.; Huang, J.; Feng, Z.; Chen, Z.; Jia, G.; et al. Recent Advances in Noncontact External-Field-Assisted Photocatalysis: From Fundamentals to Applications. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4739–4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zeng, W.; Guan, X.; Zhang, T.; Guo, L. Green Energy and Chemicals from Biomass via Thermo-Photo Catalysis: Fundamentals, Progress, and Opportunities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2026, 546, 217041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Sun, Z.; Hu, Y.H. Insights into the Thermo-Photo Catalytic Production of Hydrogen from Water on a Low-Cost NiOx-Loaded TiO2 Catalyst. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 5047–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castedo, A.; Casanovas, A.; Angurell, I.; Soler, L.; Llorca, J. Effect of Temperature on the Gas-Phase Photocatalytic H2 Generation Using Microreactors under UVA and Sunlight Irradiation. Fuel 2018, 222, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highfield, J.G.; Chen, M.H.; Nguyen, P.T.; Chen, Z. Mechanistic Investigations of Photo-Driven Processes over TiO2 by in-Situ DRIFTS-MS: Part 1. Platinization and Methanol Reforming. Energy Environ. Sci. 2009, 2, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitenko, S.I.; Chave, T.; Cau, C.; Brau, H.-P.; Flaud, V. Photothermal Hydrogen Production Using Noble-Metal-Free Ti@TiO2 Core–Shell Nanoparticles under Visible–NIR Light Irradiation. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 4790–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Chu, K.H.; Wang, B.; Wu, D.; Xie, H.; Huang, G.; Yip, H.Y.; Wong, P.K. Noble-Metal Loading Reverses Temperature Dependent Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation in Methanol–Water Solutions. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 11657–11660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Song, L.; Xu, H.; Ouyang, S. Light-Driven Low-Temperature Syngas Production from CH3OH and H2O over a Pt@SrTiO3 Photothermal Catalyst. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 2515–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhu, W.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Pyro-Photocatalytic Coupled Effect in Ferroelectric Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3 Nanoparticles for Enhanced Dye Degradation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 1276–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, V.; Choi, M.-J. Recent Progress in Pyro-Phototronic Effect-Based Photodetectors: A Path Toward Next-Generation Optoelectronics. Materials 2025, 18, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Gao, C.; Guo, J.; Ding, M.; Xu, Q.; He, S.; Mou, Y.; Dong, H.; Hu, M.; Dai, Z.; et al. A Robust Pyro-Phototronic Route to Markedly Enhanced Photocatalytic Disinfection. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 4816–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djellabi, R.; Rtimi, S. Unleashing Photothermocatalysis Potential for Enhanced Pathogenic Bacteria Inactivation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 159976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lv, G.; Liu, M.; Zhao, F.; Shuai, P.; Feng, Y.; Chen, D.; Liao, L. Photothermal-Driven Enhancing Photocatalysis and Photoelectrocatalysis: Advances and Perspectives. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 108, 332–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Chavero, M.M.; Domínguez, J.C.; Alonso, M.V.; Oliet, M.; Rodriguez, F. Thermal and Kinetics of the Degradation of Chitosan with Different Deacetylation Degrees under Oxidizing Atmosphere. Thermochim. Acta 2018, 670, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Kuate, L.J.N.; Zhang, H.; Hou, J.; Wen, H.; Lu, C.; Li, C.; Shi, W. Photothermally Enabled Black G-C3N4 Hydrogel with Integrated Solar-Driven Evaporation and Photo-Degradation for Efficient Water Purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 355, 129751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yuan, Q. Synergistic Experimental Study by a Solar Pilot Evaporation System for the Volume Reduction and Antibiotics Photocatalytic Degradation of Liquid Digestate. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 59, 105023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadizadeh, H.-S.; Goharshadi, E.K.; Karimi-Nazarabad, M. An Efficient Monolithic Green Reactor for Photo(Electro)Catalysis: Hybridizing g-C3N4 with Fe/Ni Nanoparticles on Wood Sponge for Water Oxidation, N2 and CO2 Photofixation, and Interfacial Solar Steam Generation. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, Y.; Leung, M.K.H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, K. Carbon Nitride Gels: Synthesis, Modification, and Water Decontamination Applications. Gels 2025, 11, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Yang, W.; Su, Z. Mof-Based Hydrogels with Photothermal and Photocatalytic Activity for Efficient Solar Water Evaporation and Purification. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2026, 320, 122491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Ma, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q. Biomass Hydrogel Solar-Driven Multifunctional Evaporator for Desalination, VOC Removal, and Sterilization. ACS EST Eng. 2025, 5, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, M.; Zhao, D.; Wang, Q.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Xiong, X.; Jiang, R. Multifunctional and Sustainable Chitosan-Based Interfacial Materials for Effective Water Evaporation, Desalination, and Wastewater Purification: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 321, 145973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Xing, H.; You, Y.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chu, W.; Zhang, A.; Lin, X.; Xue, J.; Lu, Y. Bioinspired Unidirectional 3D Scaffold for Synergistic Enhanced Solar Evaporation and Efficient VOCs Degradation. Small 2025, 21, 2501729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lou, J.; Ni, M.; Song, C.; Wu, J.; Dasgupta, N.P.; Tao, P.; Shang, W.; Deng, T. Bioinspired Bifunctional Membrane for Efficient Clean Water Generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Y.; Liu, X. Synchronous Steam Generation and Photodegradation for Clean Water Generation Based on Localized Solar Energy Harvesting. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 173, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, H.; Wu, S.; Gong, B.; Xu, C.; Yan, J.; Cen, K.; Bo, Z.; Ostrikov, K. High-performance Water Purification and Desalination by Solar-driven Interfacial Evaporation and Photocatalytic VOC Decomposition Enabled by Hierarchical TiO2–CuO Nanoarchitecture. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 1313–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yao, D.; Gao, X.; Lu, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Pang, X. Bio-Based Sponge-like Porous Hydrogels via Cryo-Polymerization for Efficient Solar Interfacial Evaporation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Shu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, L.; Bai, Z.; Ye, D.; Xu, J. Cellulose Nanofiber-Based Aerogel with Janus Wettability for Superior Evaporation Performance and Synergistic Photocatalytic Activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 368, 124166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, W.; Yin, G.; Gong, X. A Multifunctional Synergistic Solar-Driven Interfacial Evaporator for Desalination and Photocatalytic Degradation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 6948–6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Xiao, S.; Wang, B.; Li, Q.; Li, G.; Zhang, D.; Li, H. Self-Suspended Photothermal Microreactor for Water Desalination and Integrated Volatile Organic Compound Removal. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 51537–51545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Yang, X.; Sun, X.; Yuan, Y. Synchronizing Efficient Purification of VOCs in Durable Solar Water Evaporation over a Highly Stable Cu/W18O49@Graphene Material. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; An, X.; Guo, M. A Wood-Based Evaporator with Robust Photothermal Layer Enabling Efficient Solar Evaporation and Antibiotic Photodegradation. Water Res. 2025, 285, 124129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, J.; Wu, P.; Xia, M.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Owens, G.; Pi, K. An Integrated Photothermal–Photocatalytic Strategy for in Situ Treatment and Water Reuse of Landfill Leachate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 498, 139914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, J.; Gao, B.; Li, Q. A Self-Floating Photothermal/Photocatalytic Evaporator for Simultaneous High-Efficiency Evaporation and Purification of Volatile Organic Wastewater. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2500777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ya, Y.; Li, J.; Lai, J.; Liu, C. Plant Stem-Inspired Biomimetic Design of Hydrogel Skin-Fiber Bundle Evaporator for Dynamic Solar Treatment and Resource Re-Utilization of High-Salinity Dye Wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Qiu, J.; Li, Z.; Fu, A.; Yuan, S.; Li, H.; Lu, B. A Bifunctional Polyacrylamide-Alginate-TiO2 Hydrogel Solar Evaporator for Integrated High-Efficiency Desalination and Photocatalytic Degradation. Desalination 2025, 611, 118920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Xiao, X.; Wang, X.; Ma, Z.; Han, Y. Sodium Alginate/TiO2 Bilayer Material Multiphase Photocatalytic Degradation of Seawater Pollutants and Synergistic Seawater Evaporation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 27287–27298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, Q.; Qiu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Yuan, S.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Fu, A.; Xu, J.; Lu, B. Photothermal-Photocatalytic Bifunctional Highly Porous Hydrogel for Efficient Coherent Sewage Purification-Clean Water Generation. Desalination 2025, 597, 118364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, W.; Long, Y. Bifunctional N-TiO2/C/PU Foam for Interfacial Water Evaporation and Sewage Purification. Materials 2025, 18, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Yan, C.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y. N-Doped Fe3O4 Nanoparticles Loaded-Carbon Foam for a Highly Efficient and Recyclable Desalination-Photocatalysis Solar Evaporator. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 361, 131425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yang, X.; Wu, T.; Chen, Y.; Xie, H.; Wang, S.; Chang, Z. Antibacterial and Photocatalytic PVDF Foam for Simultaneous Interface Evaporation and Water Purification. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2026, 248, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, W.; Yang, H.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, C.; Han, Y.; Yu, Z.-Z.; Li, X. One-Step In Situ Synthesis of a Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based Hybrid Hydrogel for Highly Efficient Water Evaporation and Comprehensive Wastewater Treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 46046–46058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Kang, L.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Guo, S. Simultaneous Evaporation and Decontamination of Water on a Novel Membrane under Simulated Solar Light Irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 267, 118695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; An, L.; Liu, D.; Yao, J.; Qi, D.; Xu, H.; Song, C.; Cui, F.; Chen, X.; Ma, J.; et al. A Light-Permeable Solar Evaporator with Three-Dimensional Photocatalytic Sites to Boost Volatile-Organic-Compound Rejection for Water Purification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 9797–9805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Song, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Jia, X.; Wang, S.; Yang, X. Integrated Reduced Graphene Oxide/Polypyrrole Hybrid Aerogels for Simultaneous Photocatalytic Decontamination and Water Evaporation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 301, 120820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Yang, Y.; Xu, B.; Cai, Z. Bifunctional Fabric with Photothermal Effect and Photocatalysis for Highly Efficient Clean Water Generation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 10789–10797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liang, Q.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Ya, Y.; Li, J.; Tang, W.; Liu, C. Tilted Evaporator with “1 + 1 + 1 > 3” Synergistic Strengthening in Photothermal, Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Performance for Enhanced Treatment of High-Salinity Dye Wastewater. Desalination 2025, 615, 119270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gong, X. Hybrid Hydrogel Evaporators Integrated with the BiOI/Bi2S3 Heterojunctions for Enhanced Solar Desalination and Photocatalytic Reduction. Small 2025, 21, e03889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, T.; Ren, S.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, S.; Tang, W.; Yin, X.; Wu, T.; Gao, S. Construction of Evaporator Based on the Principle of Three Primary Colors to Achieve Synchronous Photothermal Conversion Water Evaporation and Photocatalytic Degradation. Desalination 2025, 606, 118758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Xiao, C.; Jin, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L. Bionic Solar-Driven Interfacial Evaporator for Synergistic Photothermal-Photocatalytic Activities and Salt Collection during Desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Qiu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Liu, X. Solar-Driven Ti3O5/PVA/PAM Frustum-Array Hydrogel Evaporator for Synergistic Water Purification and Photocatalytic Dye Degradation. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 74, 107654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, G.; Li, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Sui, W.; Xu, T.; Si, C. All-in-One Self-Cleaning Lignin-Derived Spherical Solar Evaporator for Continuous Desalination and Synergic Water Purification. Water Res. 2025, 282, 123932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yu, D.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yu, M. SnSe@SnO2 Core–Shell Nanocomposite for Synchronous Photothermal–Photocatalytic Production of Clean Water. Environ. Sci. Nano 2019, 6, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, H.; Wang, Y. A Bionic Solar-Driven Interfacial Evaporation System with a Photothermal-Photocatalytic Hydrogel for VOC Removal during Solar Distillation. Water Res. 2022, 226, 119276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, C.-H.; Han, S.-J.; Fu, M.-L.; Yuan, B. MXene/CdS Photothermal–Photocatalytic Hydrogels for Efficient Solar Water Evaporation and Synergistic Degradation of VOC. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 10991–11003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulani, S.R.; Bimli, S.; Patil, A.; Jadhav, H.; Miglani, A.; Ma, Y.-R.; Shaikh, P.A.; Devan, R.S. Tri-Functional MFO Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Complex Dye Removal, Salt-Resistive ISSG Membrane, and Hydrovoltaic Electricity Generation. Desalination 2025, 613, 119030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Dong, R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, F.; Tang, Y. Rationally Constructing Yolk-Shell Photothermal Material for High-Performance Water Evaporation Coupled with Volatile Organic Compound Degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Ya, Y.; Deng, D.; Liu, C. Slide-Shaped Cotton-Based Photocatalytic Solar Evaporator with Dual Mutually Strengthening Functions for Simultaneous Desalination and Dynamic Fast Dye Removal. Desalination 2024, 592, 118055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Ma, Z.; Ge, B.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, T.; Ren, G.; Zhang, Z. Interfacial Modification Strategies Enhance the Non-Wettability of Bismuth Molybdate and Its Application in Solar Evaporation and Environmental Governance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 360, 131202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, H.; Diamanti, M.V.; Lughi, V.; Rossi, S.; Meroni, D. Design Efficiency: A Critical Perspective on Testing Methods for Solar-Driven Photothermal Evaporation and Photocatalysis. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Yang, J.; Xiao, J.; Bai, B.; Wang, Q. A Janus Solar Evaporator with Photocatalysis and Salt Resistance for Water Purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 298, 121643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranova, A.; Moretti, E.; Akbar, K.; Dastgeer, G.; Vomiero, A. Emerging Strategies to Achieve Interfacial Solar Water Evaporation Rate Greater than 3 Kg·m−2·h−1 under One Sun Irradiation. Nano Energy 2024, 128, 109872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, Q.; Li, S.; Lin, M. A Comprehensive Review of Salt Rejection and Mitigation Strategies in Solar Interfacial Evaporation Systems. Desalination 2025, 600, 118507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.; Yang, Y.; Bin, X.; Zhao, S.; Pan, C.; Nawaz, F.; Que, W. Recent Advanced Self-Propelling Salt-Blocking Technologies for Passive Solar-Driven Interfacial Evaporation Desalination Systems. Nano Energy 2021, 89, 106468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, L.; Finnerty, C.; Zheng, S.; Conway, K.; Sun, L.; Ma, J.; Mi, B. Interfacial Solar Vapor Generation for Desalination and Brine Treatment: Evaluating Current Strategies of Solving Scaling. Water Res. 2021, 198, 117135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Wu, P.; Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Owens, G.; Pi, K. Tailored Iron–Polyphenol Interfacial Networks in Bio-Based Aerogels for Solar-Driven Desalination with Life Cycle Assessment Insights. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 135118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Yang, S.; Du, X.; Liu, S.; Shao, C.; Kong, H.; Wang, B.; Wu, T.; et al. Solid Waste-Derived Solar Desalination Devices: Enhanced Efficiency in Water Vapor Generation and Diffusion. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Ju, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, C.; Lu, X.; Chen, C.; et al. All-in-One Solar-Driven Evaporator for High-Performance Water Desalination and Synchronous Volatile Organic Compound Degradation. Desalination 2023, 555, 116536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jia, S.; Wu, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, F.; Liu, W. Investigation on Rapid Solar Evaporation, over 100% Evaporation Efficiency, and LCA of a Lotus-like Multi-Layer PVA-Based Aerogel. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, F.; Liu, W.; Li, F.; Hao, W.; Wang, L. Life Cycle Assessment and Energy-Exergy-Economic Performance of Solar Photovoltaic/Thermal Desalination System Integrated with Copper Coils Condensation. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siefan, A.; Rachid, E.; Elashwah, N.; AlMarzooqi, F.; Banat, F.; Van Der Merwe, R. Desalination via Solar Membrane Distillation and Conventional Membrane Distillation: Life Cycle Assessment Case Study in Jordan. Desalination 2022, 522, 115383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahramei, R.; Samimi-Akhijahani, H.; Salami, P.; Behroozi-Khazei, N. Life Cycle Assessment and CFD Evaluation of an Innovative Solar Desalination System with PCM and Geothermal System. J. Energy Storage 2025, 120, 116116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuse, C.; Tarpani, R.R.Z.; Gorgojo, P.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Azapagic, A. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Seawater Desalination Technologies Enhanced by Graphene Membranes. Desalination 2023, 551, 116418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jijakli, K.; Arafat, H.; Kennedy, S.; Mande, P.; Theeyattuparampil, V.V. How Green Solar Desalination Really Is? Environmental Assessment Using Life-Cycle Analysis (LCA) Approach. Desalination 2012, 287, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, M.F.; Fong, K.C.; Ghafoor, F.; Azhar, U.; Rabani, I. Solar Vapor Generation: Advances in Materials Engineering and Structural Design for Efficient Water Evaporation. Mater. Today Phys. 2025, 59, 101938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, R.; Zhuo, S.; Jin, Y.; Shi, L.; Hong, S.; Chang, J.; Ong, C.; Wang, P. Solar Evaporator with Controlled Salt Precipitation for Zero Liquid Discharge Desalination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 11822–11830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.-J.; Liu, Y.-D.; Wu, S.-M.; Tian, G.; Yang, X.-Y. Towards Durable Photocatalytic Seawater Splitting: Design Strategies and Challenges. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 15087–15103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entezami, N.; Farhadian, M.; Davari, N. Removal of Metronidazole Antibiotic Pharmaceutical from Aqueous Solution Using TiO2/Fe2O3/GO Photocatalyst: Experimental Study on the Effects of Mineral Salts. Adv. Environ. Technol. 2019, 5, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yin, J.L.; Li, B.; Ye, Z.; Liu, D.; Ding, D.; Qian, F.; Myung, N.V.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, Y. Janus Evaporators with Self-Recovering Hydrophobicity for Salt-Rejecting Interfacial Solar Desalination. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 17419–17427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Shi, W.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Tong, X.; Wang, Z. Janus Membranes at the Water-Energy Nexus: A Critical Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 318, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, D.; Xu, F.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, J. Bioinspired Photothermal Conversion Coatings with Self-Healing Superhydrophobicity for Efficient Solar Steam Generation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 24441–24451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Zhong, Y.; Leroy, A.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wang, E.N. Highly Efficient and Salt Rejecting Solar Evaporation via a Wick-Free Confined Water Layer. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Y.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, J. A 3D Conical Solar Evaporator with Vertically Aligned Microchannels and Diatomite Synergy for High-Efficiency Salt-Resistant Desalination. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 15208–15225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Zhan, F.; Liang, H.; Chen, L.; Lan, D. Chemical Grafting of Nano-TiO2 onto Carbon Fiber via Thiol–Ene Click Chemistry and Its Effect on the Interfacial and Mechanical Properties of Carbon Fiber/Epoxy Composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 2594–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.-Q.; Tan, C.F.; Lu, W.; Zeng, K.; Ho, G.W. Spectrum Tailored Defective 2D Semiconductor Nanosheets Aerogel for Full-Spectrum-Driven Photothermal Water Evaporation and Photochemical Degradation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2004460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PT Class | Active Material(s) Proposed | PT Material | PC Material | PT + PC Enhancement | Evaporation Rate (kg·m−2·h−1) | Target PC Molecule | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noble metal based | Silk fibroin/Ag2S/Ag3PO4 | Ag2S | Ag3PO4 | - | 2.86 @1 sun | Phenol | [144] |

| Ag-MOF | Ag-MOF | Ag-MOF | - | 1.92 @1 sun | RhB | [41] | |

| AuNP@TiO2 | AuNP | TiO2 | Yes | 1.3 mg/s @5 sun | RhB | [35] | |

| AAO@AuNP@TiO2 | AuNP | TiO2 | No | 5 @6.7 sun | RhB | [145] | |

| AuNP@ZnO | AuNP | ZnO | - | 1 @1 sun | RhB | [146] | |

| TiO2/CuO/Cu | CuO | TiO2 | Yes | 1.28 @1 sun | Phenol | [147] | |

| Chitosan/PAA/CuS | CuS | Chitosan | - | 2.79 @1 sun | MB | [148] | |

| CuS@CNF/PVA | CNF | CuS | - | 3.2 @1 sun | Dyes | [149] | |

| PPy/CuO | CuO | PPy | - | 1.48 @1 sun | MB | [150] | |

| Carbon based | TiO2 on carbon | C | TiO2 | Yes | 1 @1 sun | Phenol | [151] |

| Cu/W18O49@Graphene | Graphene | W18O49 | Yes | 1.41 @1 sun | Phenol | [152] | |

| Fe3O4/CNT | CNT | Fe3O4 | Yes | 1.76 @1 sun | Tetracycline | [153] | |

| NiO-TiO2-CNT | CNT | NiO-TiO2 | - | 2.25 @1 sun | Phenol | [154] | |

| Mn@g-C3N4/PANI/carbon | g-C3N4/PANI/C | Mn@g-C3N4 | No | 2.99 @1 sun | Phenol | [155] | |

| rGO + g-C3N4 | rGO + g-C3N4 | g-C3N4 | - | 2.55 @1 sun | Dyes | [156] | |

| TiO2@C/PAM | C | TiO2 | No | 2.97 @1 sun | MB | [157] | |

| Carbonized sodium alginate/TiO2 | C | TiO2 | - | 2.11 @2.5 sun | RhB | [158] | |

| TiO2/SWCNTs/ Polyacrylamide | CNTs | TiO2 | - | 3.53 @1 sun | MB | [159] | |

| N-TiO2/C | C | TiO2 | - | 1.73 @1 sun | RhB | [160] | |

| N-Fe2O3/carbon | C | N-Fe2O3 | Yes | 1.53 @1 sun | MB | [161] | |

| PVDF/TiO2/GO | PVDF/GO | TiO2 | - | 1.48 @1 sun | RhB | [162] | |

| GO/TiO2/PANI | GO/PANI | TiO2 | Yes | 2.81 @1 sun | Dyes, antibiotics | [163] | |

| MoO3−x + BiOCl + CNTs | MoO3−x, CNTs | BiOCl | - | 7.75 @5 sun | Toluene | [164] | |

| BiOBrI on carbon | C | BiOBrI | - | 1.67 @1 sun | Phenol | [165] | |

| Graphene/PPY | Graphene, PPY | PPY | Yes | 2.08 @1 sun | Phenol | [166] | |

| Other | TiO2−PDA/PPy/cotton | PPY | TiO2 | Yes | 1.55 @1 sun | MO | [167] |

| Ag-PPy-TiO2 | PPy | TiO2 | Yes | 1.8 @1 sun | MO | [168] | |

| BiOI/Bi2S3/PVA | Bi2S3 | BiOI | - | 2.34 @1 sun | Cr (VI) | [169] | |

| TiO2−x/BiOI | BiOI | TiO2−x/BiOI | No | 2.5 @1 sun | RhB | [170] | |

| PPy/BiVO4-PI/MXene | PI/MXene | PPY/BiVO4 | - | 1.64 @1 sun | Dyes | [171] | |

| Ti3O5/PVA/PAM | Ti3O5 | Ti3O5 | - | 4.34 @1 sun | MB | [172] | |

| Carbon-doped g-C3N4 | g-C3N4 | g-C3N4 | - | 1.64 @1 sun | Tetracycline | [173] | |

| SnSe@SnO2 | SnSe | SnO2 | Yes | 1.19 @1 sun | RhB | [174] | |

| TiO2/Ti3C2/C3N4/PVA | Ti3C2/C3N4 | TiO2 | Yes | 1.54 @1 sun | Phenol | [175] | |

| Ti3C2 MXene + CdS | Ti3C2 | CdS | Yes | 1.8 @1 sun | RhB, phenol | [176] | |

| TiO2 on SiO2 | SiO2 | TiO2 | - | 1.71 @1 sun | Phenol | [16] | |

| MnFeO3 | MnFeO3 | MnFeO3 | - | 2.28 @1 sun | Dyes | [177] | |

| MXene-TiO2-Ag | MXene | TiO2 | Yes | 3.09 @1 sun | Phenol | [42] | |

| LaCoO3/MoS2 | MoS2 | LaCoO3 | Yes | 5.27 @1 sun | Dyes, phenol | [178] | |

| MnO2-TiO2 | MnO2 | TiO2 | Yes | 1.68 @1 sun | MB | [179] | |

| Bi2MoO6/polydopamine | Polydopamine | Bi2MoO6 | - | 2.1 @1 sun | RhB | [180] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meroni, D.; Hamza, H.; Lughi, V.; Diamanti, M.V. Balancing Photocatalytic and Photothermal Elements for Enhanced Solar Evaporation—A Review. Catalysts 2026, 16, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020157

Meroni D, Hamza H, Lughi V, Diamanti MV. Balancing Photocatalytic and Photothermal Elements for Enhanced Solar Evaporation—A Review. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020157

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeroni, Daniela, Hady Hamza, Vanni Lughi, and Maria Vittoria Diamanti. 2026. "Balancing Photocatalytic and Photothermal Elements for Enhanced Solar Evaporation—A Review" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020157

APA StyleMeroni, D., Hamza, H., Lughi, V., & Diamanti, M. V. (2026). Balancing Photocatalytic and Photothermal Elements for Enhanced Solar Evaporation—A Review. Catalysts, 16(2), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020157