Effects of Reaction Atmospheres on Hydrogenation Selectivity of Bicyclic Aromatics on NiMoS Active Sites—Combining DFT Calculation and Experiments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Hydrogenation of 1-MN on Ni-Mo-S Active Sites

2.2. Effects of Additives in Atmosphere on 1-MN Conversion

2.3. Effects of Additive in Atmosphere on RRMA

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Section

3.2. Computational Section

3.2.1. Modeling

3.2.2. Calculation Method

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BTX | Benzene–Toluene–Xylene |

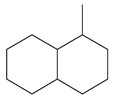

| 1-MN | 1-Methylnaphthalene |

| MTHN | Methyl-tetrahydronaphthalene |

| MDHN | Methyl-decahydronaphthalene |

| 5-MTHN | 5-Methyltetrahydronaphthalene |

| 1-MTHN | 1-Methyltetrahydronaphthalene |

| 1-MDHN | 1-Methyldecahydronaphthalene |

| IBAs | Isomeric bicyclic alkanes |

| CUSs | Coordination-unsaturated sites |

| WHSV | Weight hourly space velocity |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

References

- Skeer, J.; Boshell, F.; Ayuso, M. Technology Innovation Outlook for Advanced Liquid Biofuels in Transport. Acs Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 724–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, E.; Thorkelsson, H.; Asgeirsson, E.I.; Davidsdottir, B.; Raberto, M.; Stefansson, H. An agent-based modeling approach to predict the evolution of market share of electric vehicles: A case study from Iceland. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2024, 79, 1638–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giechaskiel, B.; Joshi, A.; Ntziachristos, L.; Dilara, P. European Regulatory Framework and Particulate Matter Emissions of Gasoline Light-Duty Vehicles: A Review. Catalysts 2019, 9, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. Crucial technologies supporting future development of petroleum refining industry. Chin. J. Catal. 2013, 34, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wei, X.; Shou, S.; Gong, J. Dealkylation in Fluid Catalytic Cracking Condition for Efficient Conversion of Heavy Aromatics to Benzene–Toluene–Xylene. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 10789–10795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wu, X.; Yu, G.; Xi, L.; Zou, H.; Wu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, Z. Study of aromatic extraction from light cycle oil from the viewpoint of industrial applications. Fuel 2024, 357, 130023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Mei, J.; Guo, R.; Wu, Z.; Hou, S.; Peng, S.; Fan, S.; Peng, C.; Duan, A. Hydrocracking Straight-Run Diesel into High-Value Chemical Materials: The Effect of Acidity and Kinetic Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 8685–8697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Yan, S.; He, N.; Nie, H.; Guo, L.; Xiong, G.; Wang, N.; Liu, J.; Li, M. The effect of accessibility to acid sites in Y zeolites on ring opening reaction in light cycle oil hydrocracking. Chem. Synth. 2025, 5, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, G.; Weng, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X. High value utilization of inferior diesel for BTX production: Mechanisms, Catalysts, Conditions and Challenges. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2021, 616, 118095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laredo, G.C.; Pérez-Romo, P.; Escobar, J.; Garcia-Gutierrez, J.L.; Vega-Merino, P.M. Light cycle oil upgrading to benzene, toluene, and xylenes by hydrocracking: Studies using model mixtures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 10939–10948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngseok, O.; Jaeuk, S.; Haeseong, N.; Chanwoo, K.; Yong, S.K.; Yong, K.L.; Jung, K.L. Selective hydrotreating and hydrocracking of FCC light cycle oil into high-value light aromatic hydrocarbons. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2020, 577, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramone, A.R.; Resasco, D.E.; Alvarez, W.E.; Choudhary, T.V. Simultaneous Hydrogenation of Multiring Aromatic Compounds over NiMo Catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 7161–7166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulhoat, H. A perspective on the catalytic hydrogenation of aromatics by Co(Ni)MoS phases. J. Catal. 2021, 403, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yuan, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, X.; Peng, J.; Pan, Y. Rational design principles of single-atom catalysts for hydrogen production and hydrogenation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 8019–8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Peng, S.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, L. Development and application of FF-46 catalyst for hydrocracking feedstocks pretreatment. Pet. Process. Petrochem. 2012, 43, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Guan, M. Research Progress in Hydrocracking Pretreatment Catalysts at Home and Abroad. Contem. Chem. Ind. 2012, 41, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, Z.; Eller, Z.; Hancsok, J. Techno-economic evaluation of quality improvement of heavy gas oil with different processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulshin, P.; Salnikov, V.; Mozhaev, A.; Minaev, P.; Kogan, V.; Pimerzin, A. Relationship between active phase morphology and catalytic properties of the carbon–alumina-supported Co (Ni) Mo catalysts in HDS and HYD reactions. J. Catal. 2014, 309, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Fang, X.; Zeng, R. Research and development of hydrocracking catalysts and technology. In Catalysis; Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC): London, UK, 2016; Volume 28, pp. 86–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Q.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, P. Substitution of Sulfur Atoms on Ni-Mo-S by Ammonia—A DFT Study. Catal. Today 2020, 353, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.T.; Park, D.R.; Yoo, S.J.; Kim, J.D.; Park, H.S. Characterization of the active phase of NiMo/Al2O3 hydrodesulfurization catalysts. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2006, 32, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, H.; Raybaud, P.; Toulhoat, H. Promoter sensitive shapes of Co (Ni) MoS nanocatalysts in sulfo-reductive conditions. J. Catal. 2002, 212, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, E.; Silvi, B.; Daudin, A.; Raybaud, P. A DFT study of the origin of the HDS/HydO selectivity on Co(Ni)MoS active phases. J. Catal. 2008, 260, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, E.; Daudin, A.; Raybaud, P. A DFT Study of CoMoS and NiMoS Catalysts: From Nano-Crystallite Morphology to Selective Hydrodesulfurization. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. 2009, 64, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahadriansya, T.; Oemry, F.; Adilina, I.B.; Effendi, M.; Cahyanto, W.T. Oxygen-induced SO2 formation and desorption on NiMoS (1010) edge surface on NiMoS2 catalyst. AIP Confer. Proceed. 2024, 3003, 020017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.K.; Zhao, X.G.; Wang, L.X.; Li, H.F. Study on Adsorption of Diesel Molecules on MoS2 and NiMoS Catalysts. Mater. Sci. Forum 2024, 1112, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.J.; Peng, S.Z.; Yan, Z.J.; Wang, J.F.; Jiang, S.J.; Yang, Z.L. Charge effects on quinoline hydrodenitrogenation catalyzed by Ni-Mo-S active sites-A theoretical study by DFT calculation. Petrol. Sci. 2022, 19, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, S.; Peng, S.; Yang, Z.; Du, Y. Competitive and sequence reactions of typical hydrocarbon molecules in diesel fraction hydrocracking—A theoretical study by DFT calculations. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 19537–19547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Q.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, W. Substituent effects of 4,6-DMDBT on direct hydrodesulfurization routes catalyzed by Ni-Mo-S active nanocluster-A theoretical study. Catal. Today 2017, 305, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Jiang, S.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Yang, Z. Effects of the Ni-Mo ratio on olefin selective hydrogenation catalyzed on Ni-Mo-S active sites: A theoretical study by DFT calculation. Fuel 2020, 277, 118136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Ding, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, S.; Geng, X.; Cao, Z. Substituent Effects of the Nitrogen Heterocycle on Indole and Quinoline HDN Performance: A Combination of Experiments and Theoretical Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs, E.; Silvi, B.; Raybaud, P. Mixed sites and promoter segregation: A DFT study of the manifestation of Le Chatelier’s principle for the Co(Ni)MoS active phase in reaction conditions. Catal. Today 2008, 130, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, E.; Constantin, L.A.; Della Sala, F. Erratum: Testing the broad applicability of the PBEint GGA functional and its one-parameter hybrid form. Int. J. Quantum. Chem. 2013, 113, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, Y.; Orita, H. Efficiency of numerical basis sets for predicting the binding energies of hydrogen bonded complexes: Evidence of small basis set superposition error compared to Gaussian basis sets. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 29, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delley, B. Efficient and accurate expansion methods for molecules in local density models. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 76, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigo Anota, E.; Cocoletzi, G.H. GGA-based analysis of the metformin adsorption on BN nanotubes. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostructures 2014, 56, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S. Density functional theory with London dispersion correction. WIREs Comput. Moleclul. Sci. 2011, 1, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Nelson, A.E.; Adjaye, J. Ab initio DFT study of hydrogen dissociation on MoS 2, NiMoS, and CoMoS: Mechanism, kinetics, and vibrational frequencies. J. Catal. 2005, 233, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.; Xiao, P.; Chemelewski, W.; Johnson, D.D.; Henkelman, G. A generalized solid-state nudged elastic band method. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 074103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.W.; Trout, B.L.; Brooks, B.R. A super-linear minimization scheme for the nudged elastic band method. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 12708–12717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Products | 1−MN | 5−MTHN | 1−MTHN | IBAs | 1−MDHN | Liquid Yield wt% | RRMA % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Formula |  |  |  |  |  | ||

| Temperature/°C | Content/wt.% | ||||||

| 260 | 91.5 | 6.2 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 100.4 | 100.0 |

| 270 | 55.6 | 32.5 | 11.9 | 0 | 0 | 100.6 | 100.0 |

| 280 | 31.9 | 47.6 | 16.8 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 100.3 | 94.6 |

| 290 | 5.5 | 56.7 | 23.8 | 2.5 | 11.5 | 100.4 | 85.2 |

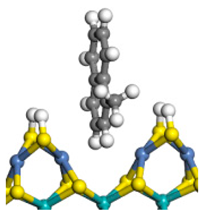

| Adsorption Location | Morphology | Adsorption Enthalpy/kJ·mol−1 | Charge Transfer/e |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-S-edge |  | −84.68 | 0.092 |

| −73.48 | 0.075 | |

| −54.52 | 0.061 | |

| Ni-Mo-edge |  | −146.36 | 0.167 |

| −81.05 | 0.081 |

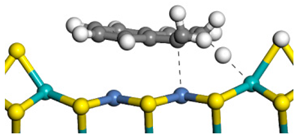

| Adsorption Location | S-Edge | |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen transfer position | Ring without methyl groups | Ring with methyl groups |

| Reaction |  |  |

| Pre-hydrogen transfer |  |  |

| Transition state |  |  |

| Post-hydrogen transfer |  |  |

| Reaction energy kJ/mol | +56.26 | +103.09 |

| Activation energy kJ/mol | +116.98 | +158.32 |

| Adsorption Location | Mo-Edge | |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen transfer position | Ring without methyl groups | Ring with methyl groups |

| Reaction |  |  |

| Pre-hydrogen transfer |  |  |

| Transition state |  |  |

| Post-hydrogen transfer |  |  |

| Reaction energy kJ/mol | +57.90 | +68.54 |

| Activation energy kJ/mol | +113.09 | +129.48 |

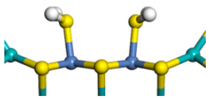

| HOMO of H2S | Location | Number of Adsorption Molecules | Adsorption Morphology | Adsorption Enthalpy kJ/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-edge | 1 |  | −78.85 |

| Mo-edge | 1 |  | −54.68 | |

| Mo-edge | 2 |  | −89.14 |

| Products | 1-MN | 5-MTHN | 1-MTHN | IBAs | 1-MDHN | Liquid Yield wt% | RRMA % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Formula |  |  |  |  |  | |||

| Reaction Temperature/°C | H2S Partial Pressure/MPa | Content/wt.% | ||||||

| 270 | 0 | 55.6 | 32.5 | 11.9 | - | - | 100.5 | 100.0 |

| 0.1 | 71.8 | 16.9 | 11.3 | - | - | 100.5 | 100.0 | |

| 0.2 | 77.7 | 12.6 | 9.7 | - | - | 100.6 | 100.0 | |

| 280 | 0 | 31.9 | 47.6 | 16.8 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 100.3 | 94.6 |

| 0.1 | 38.2 | 34.8 | 25.2 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 100.2 | 97.1 | |

| 0.2 | 48.5 | 27.4 | 23.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 100.4 | 98.8 | |

| 290 | 0 | 7.5 | 55.7 | 22.8 | 2.5 | 11.5 | 100.4 | 84.9 |

| 0.1 | 14.6 | 41.1 | 36.4 | 1.1 | 6.8 | 100.1 | 90.7 | |

| 0.2 | 20.3 | 38.9 | 35.7 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 100.2 | 93.6 | |

| HOMO of NH3 | Location | Number of Adsorption Molecules | Adsorption Morphology | Adsorption Enthalpy kJ/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-edge | 1 |  | −90.35 |

| Mo-edge | 1 |  | −114.42 | |

| Mo-edge | 2 |  | −205.37 |

| Products | 1-MN | 5-MTHN | 1-MTHN | IBAs | 1-MDHN | Liquid Yield wt% | RRMA % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Formula |  |  |  |  |  | |||

| Reaction Temperature/°C | NH3 Partial Pressure/MPa | Content/wt.% | ||||||

| 270 | 0 | 55.6 | 32.5 | 11.9 | 0 | 0 | 100.6 | 100.0 |

| 0.02 | 68.4 | 25.1 | 6.5 | 0 | 0 | 100.4 | 100.0 | |

| 0.04 | 76.0 | 20.6 | 3.4 | 0 | 0 | 100.9 | 100.0 | |

| 0.1 | 88.3 | 8.6 | 3.1 | 0 | 0 | 101.1 | 100.0 | |

| 280 | 0 | 31.9 | 47.6 | 16.8 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 100.3 | 94.6 |

| 0.02 | 45.4 | 40.3 | 11.9 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 100.6 | 95.6 | |

| 0.04 | 55.3 | 36.0 | 6.9 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 100.8 | 96.0 | |

| 0.1 | 68.4 | 28.2 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 101.4 | 96.9 | |

| 290 | 0 | 7.5 | 55.7 | 22.8 | 2.5 | 11.5 | 100.4 | 84.9 |

| 0.02 | 21.5 | 50.4 | 17.5 | 2 | 8.6 | 100.5 | 86.5 | |

| 0.04 | 34.8 | 44.2 | 12.5 | 1.4 | 6.1 | 100.7 | 88.3 | |

| 0.1 | 52.2 | 37.1 | 6.2 | 0.8 | 3.7 | 101.2 | 90.6 | |

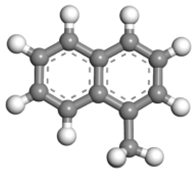

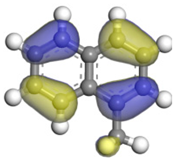

| Hydrocarbons | 1-MN | 1-MTHN | 5-MTHN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural formula |  |  |  |

| HOMO |  |  |  |

| Eigenvalues/eV | −5.34 | −5.55 | −5.43 |

| Adsorption morphology on S-edge |  |  |  |

| Adsorption enthalpy/kJ·mol−1 | −84.68 | −79.51 | −88.75 |

| Charge transfer/e | 0.092 | 0.128 | 0.142 |

| Adsorption morphology on Mo-edge |  |  |  |

| Adsorption enthalpy/kJ·mol−1 | −146.36 | −78.10 | −68.20 |

| Charge transfer/e | 0.167 | 0.086 | 0.061 |

| Products | 1-MN | 5-MTHN | 1-MTHN | IBAs | 1-MDHN | Liquid Yield % | RRMA % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Formula |  |  |  |  |  | ||||

| Reaction Temperature/°C | Additive | Partial Pressure/MPa | Content/wt.% | ||||||

| 290 | / | 0 | 7.5 | 55.7 | 22.8 | 2.5 | 11.5 | 100.4 | 84.9 |

| H2S | 0.1 | 14.6 | 41.1 | 36.4 | 1.1 | 6.8 | 100.1 | 90.7 | |

| H2S | 0.2 | 20.3 | 38.9 | 35.7 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 100.2 | 93.6 | |

| NH3 | 0.04 | 34.8 | 44.2 | 12.5 | 1.4 | 6.1 | 100.7 | 88.3 | |

| NH3 | 0.1 | 52.2 | 37.1 | 6.2 | 0.8 | 3.7 | 101.2 | 90.6 | |

| 300 | / | 0 | 0.8 | 40.1 | 17.3 | 5.1 | 36.7 | 99.7 | 58.8 |

| H2S | 0.1 | 3.5 | 52.9 | 20.6 | 3.9 | 21.1 | 99.9 | 74.6 | |

| H2S | 0.2 | 6.2 | 64.0 | 23.1 | 0.3 | 6.4 | 100.2 | 92.9 | |

| NH3 | 0.04 | 10.2 | 45.4 | 20.5 | 3.3 | 20.6 | 100.5 | 73.4 | |

| NH3 | 0.1 | 18.6 | 50.7 | 22.5 | 1.4 | 6.8 | 100.9 | 89.9 | |

| Item | Parameter |

|---|---|

| MoO3 wt.% | 13–18 |

| NiO wt.% | 3.0–5.0 |

| Supports | γ-Al2O3 |

| Specific surface area/m2·g−1 | 160–200 |

| Pore volume/cm3·g−1 | 0.4–0.6 |

| Length/nm | Proportion/% | Stack Layer | Proportion/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| <5 | 14.2 | 1 | 70.5 |

| 5–8 | 76.4 | 2 | 21.1 |

| >8 | 9.4 | ≥3 | 8.4 |

| Average Length/nm | 6.6 | Average Stack Layer | 1.4 |

| Items | Parameter | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functions | General gradient approximation–Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof function (GGA-PBE) [33] | |||

| Basis set | Double numerical plus polarization basis (DNP) [34,35] | |||

| Electron spin | Open shell | |||

| Symmetry | Asymmetry | |||

| Self-consistent field density convergence (SCF) | 1 × 10−5 | |||

| Thermal smearing | 2 × 10−4 Hartree (Ha) | |||

| Orbital cut-off | 4.9 angstroms (Å) | |||

| Core treatment | Effective core potentials (ECPs) | |||

| Dispersion correction | Grimme 06 [36,37] | |||

| Exchange–correlation Dependent factor, s6 | 0.75 | |||

| Damping coefficient, d | 20.0 | |||

| Grimme 6.0 atomic dispersion parameters [38,39] | Element | Interaction distance R0 | Dispersion coefficient C6 | |

| H | 1.001 | 1.451 | ||

| C | 1.452 | 18.134 | ||

| N | 1.397 | 12.748 | ||

| S | 1.683 | 57.729 | ||

| Ni | 1.562 | 111.943 | ||

| Mo | 1.639 | 255.686 | ||

| Geometry optimization | Energy tolerance | 1 × 10−5 Hartree (Ha) | ||

| Force tolerance | 3 × 10−3 Ha/Å | |||

| Transition state | Transition state search | Complete linear synchronous transit (LST) and quadratic synchronous transit (QST) methods [40] | ||

| RMS force | 0.003 Ha/Å | |||

| Transition state confirmation | Nudged elastic band (NEB) method [41,42] | |||

| Transition state optimization | Eliminating redundant imaginary frequencies | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ding, S.; Wang, T.; Gao, H.; Jiang, Q.; Ma, J.; Lu, W.; Jia, Z.; Yang, Z.; Peng, S.; Wang, J. Effects of Reaction Atmospheres on Hydrogenation Selectivity of Bicyclic Aromatics on NiMoS Active Sites—Combining DFT Calculation and Experiments. Catalysts 2026, 16, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020122

Ding S, Wang T, Gao H, Jiang Q, Ma J, Lu W, Jia Z, Yang Z, Peng S, Wang J. Effects of Reaction Atmospheres on Hydrogenation Selectivity of Bicyclic Aromatics on NiMoS Active Sites—Combining DFT Calculation and Experiments. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020122

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Sijia, Tao Wang, Hang Gao, Qianmin Jiang, Jun Ma, Wenduo Lu, Zixian Jia, Zhanlin Yang, Shaozhong Peng, and Jifeng Wang. 2026. "Effects of Reaction Atmospheres on Hydrogenation Selectivity of Bicyclic Aromatics on NiMoS Active Sites—Combining DFT Calculation and Experiments" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020122

APA StyleDing, S., Wang, T., Gao, H., Jiang, Q., Ma, J., Lu, W., Jia, Z., Yang, Z., Peng, S., & Wang, J. (2026). Effects of Reaction Atmospheres on Hydrogenation Selectivity of Bicyclic Aromatics on NiMoS Active Sites—Combining DFT Calculation and Experiments. Catalysts, 16(2), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020122