End-Functionalization in Coordination Chain Transfer Polymerization of Conjugated Dienes

Abstract

1. Introduction

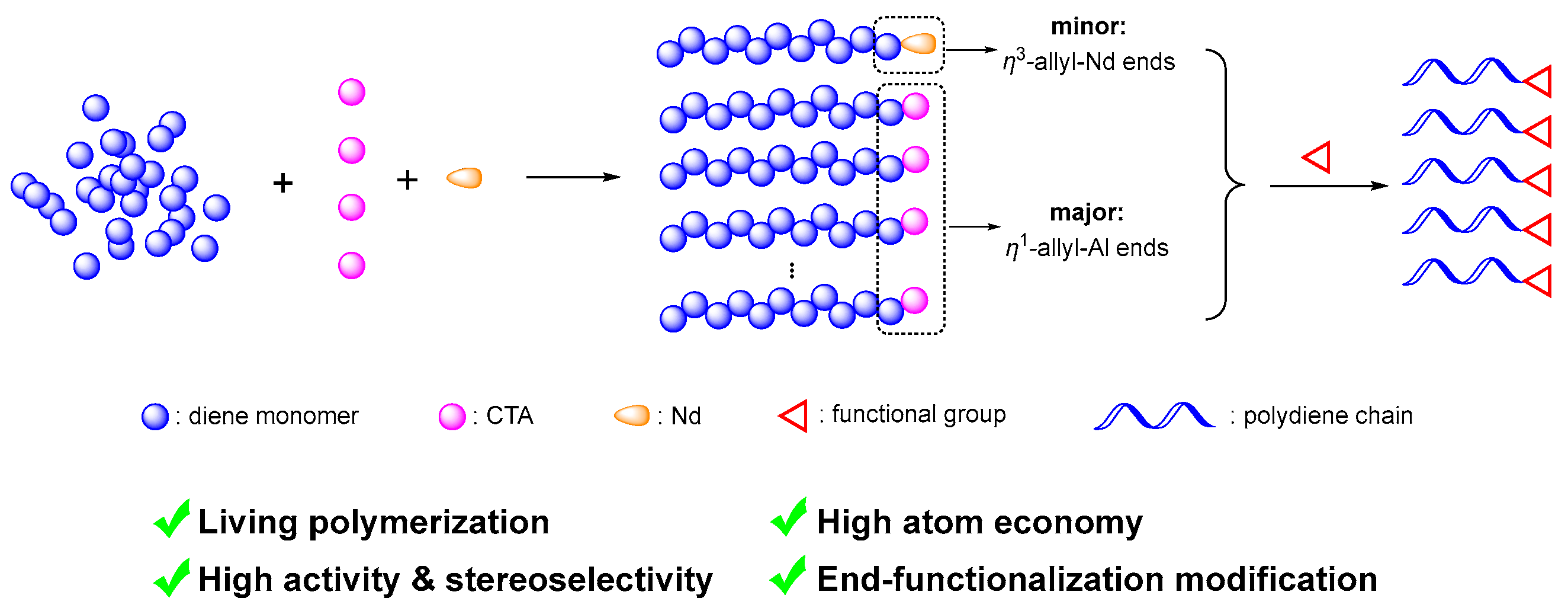

2. Coordination Chain Transfer Polymerization

2.1. Principle of Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerization

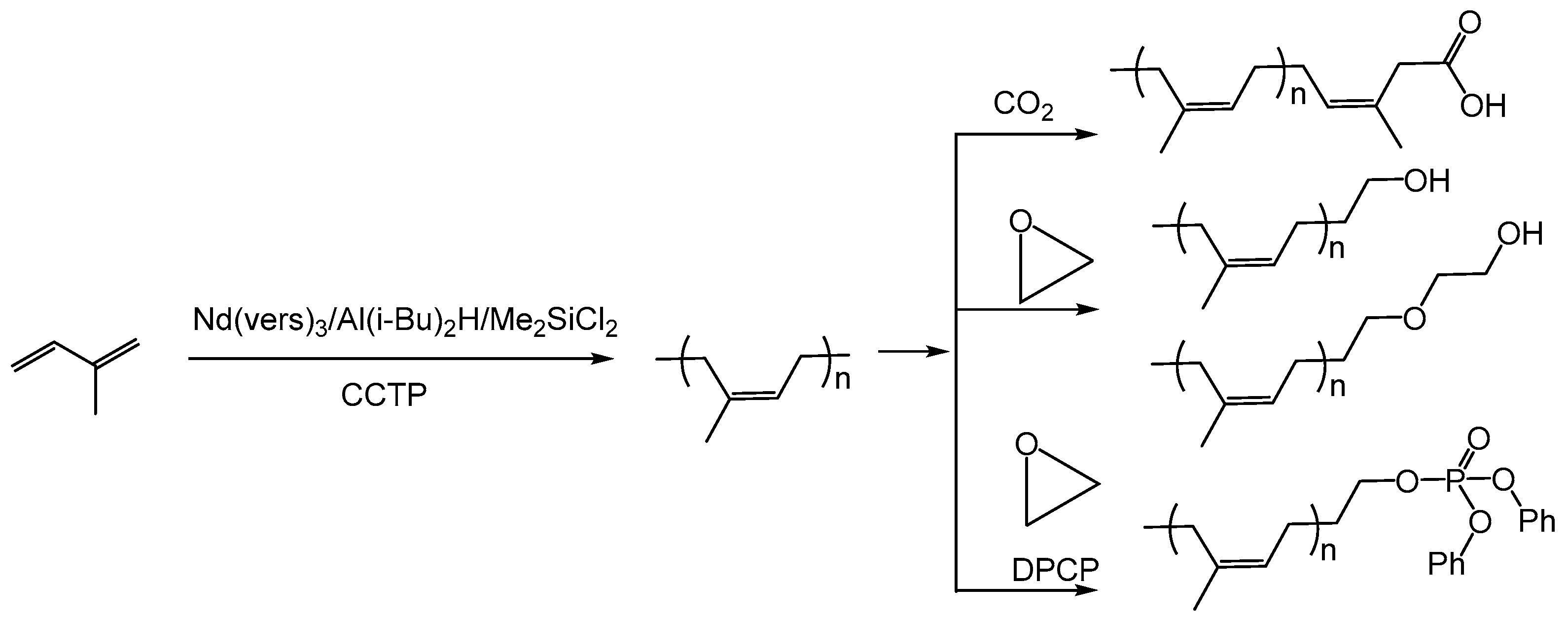

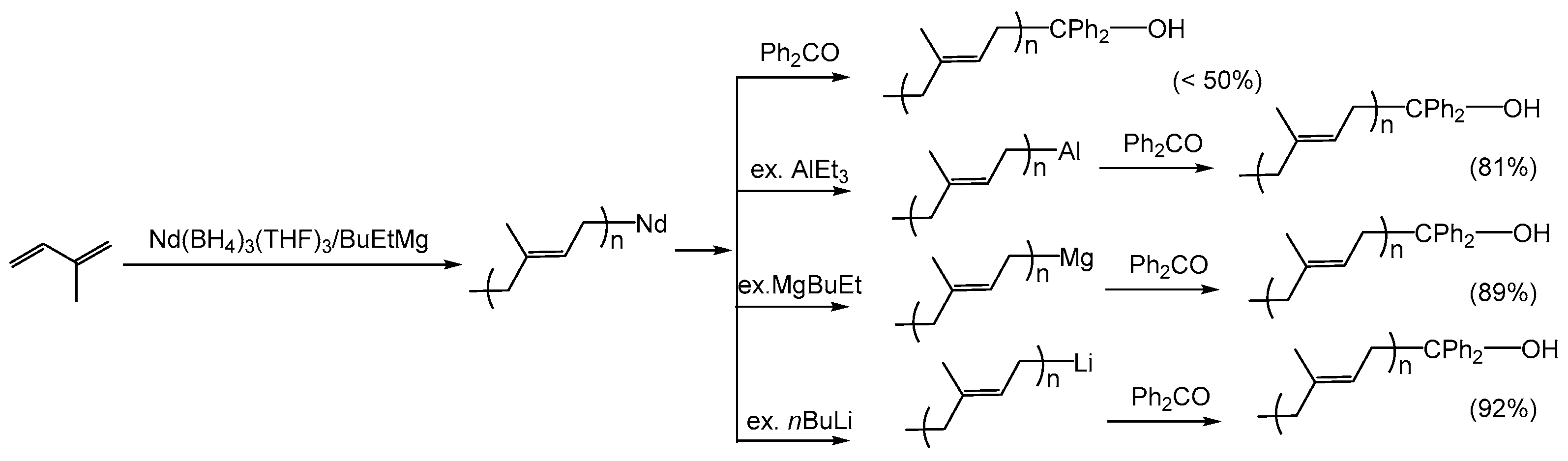

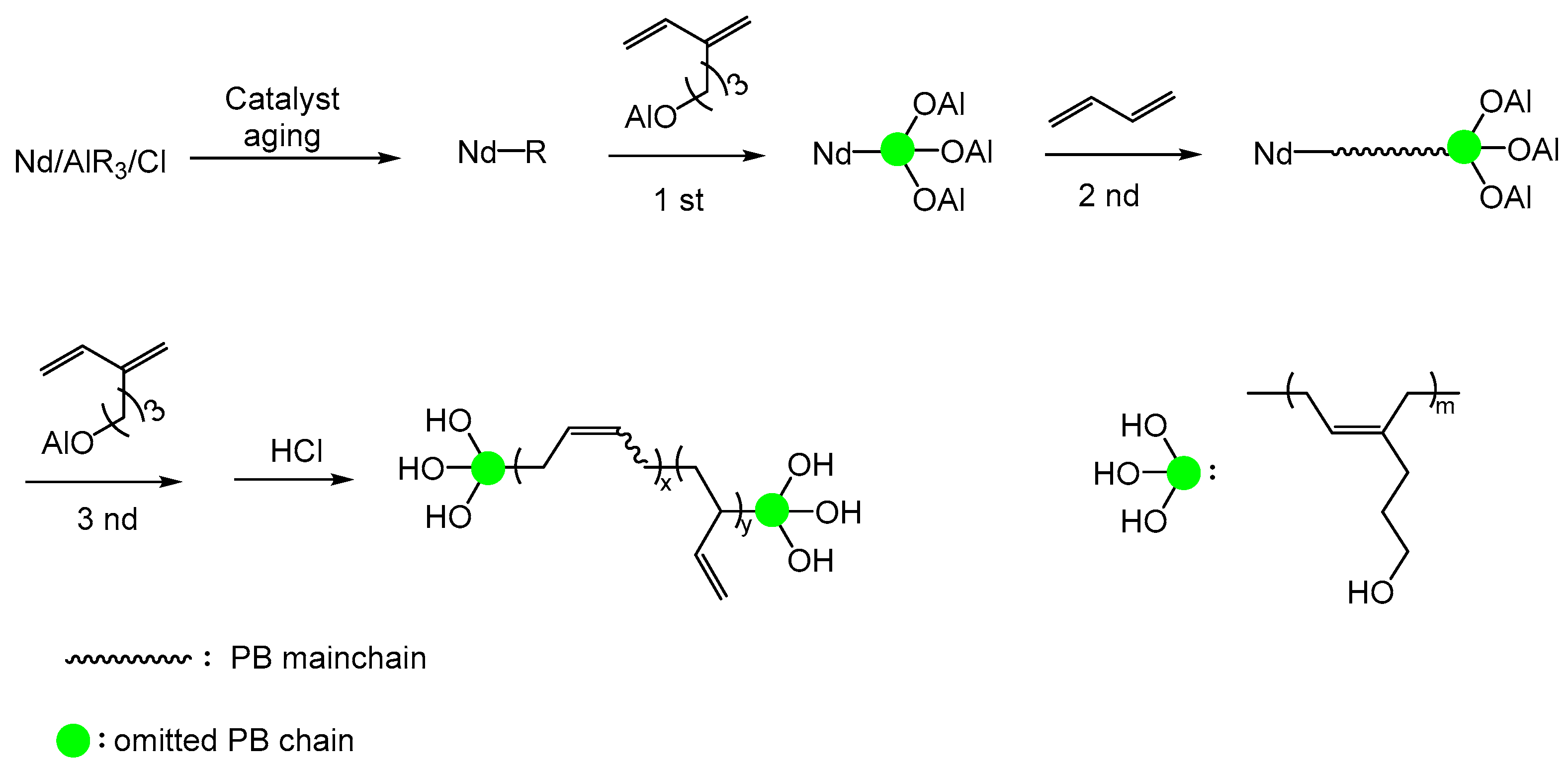

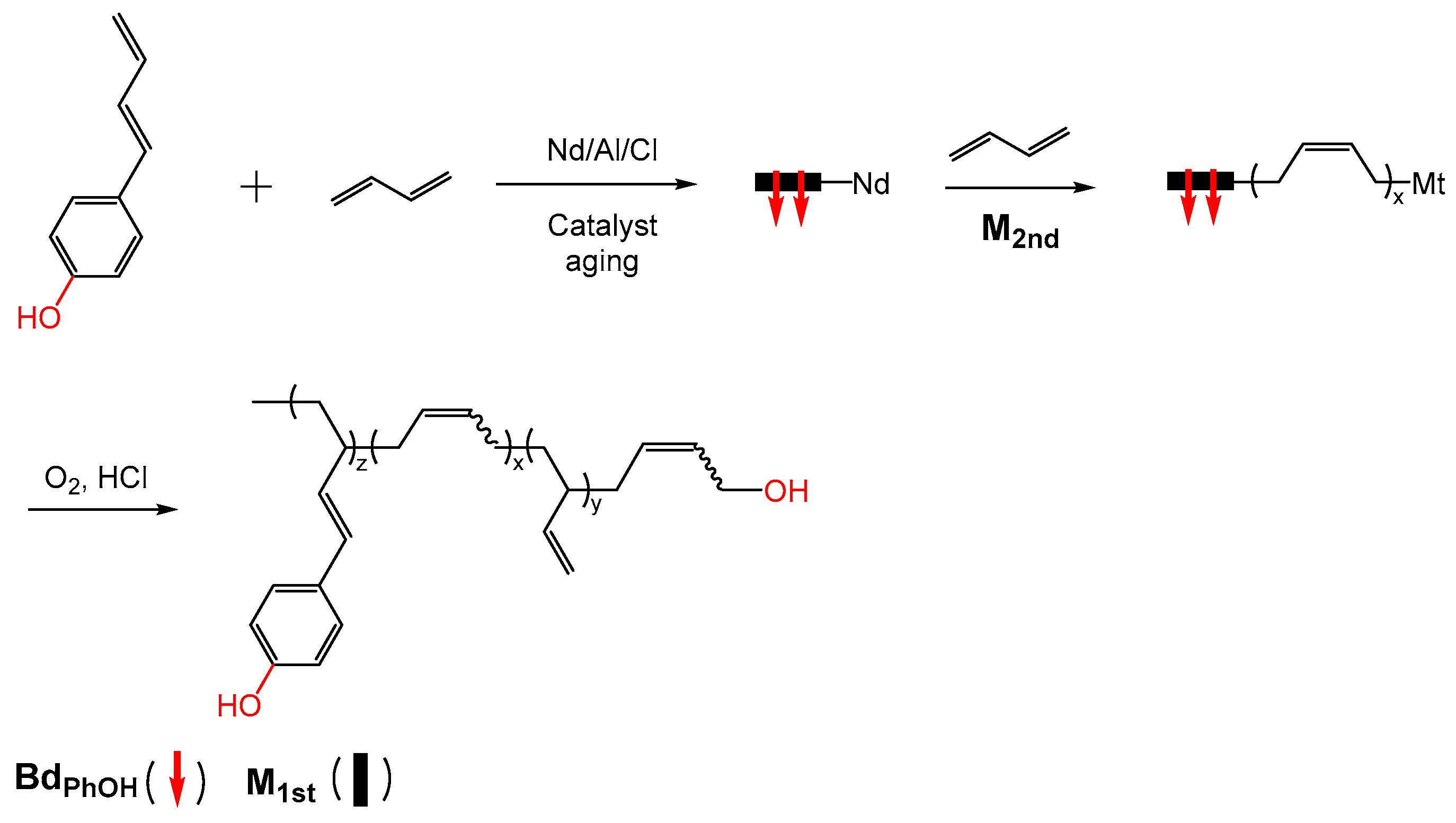

2.2. End-Functionalization Modification of Dienes via CCTP

2.2.1. Polyisoprene

2.2.2. Polybutadiene

2.2.3. Other Polydienes

3. Conclusions and Outlooks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PB | Polybutadiene rubber |

| PI | Polyisoprene rubber |

| SBR | Styrene-butadiene rubber |

| CCTP | Coordination chain transfer polymerization |

| CTA | Chain transfer agent |

| PDI | Molecular weight distribution |

| CCTcoP | Coordination chain transfer copolymerization |

| DPCP | Diphenyl chlorophosphite |

| UPy | 2-Ureido-4[H]-pyrimidinone |

| CB | Carbon black |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| DIC | N,N-diisopropylcarbodiimide |

| HDI | Hexamethylene diisocyanate |

| HTPB | Hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene |

| BOMAG | n-Butyl-n-octyl magnesium |

| EBR | Ethylene-butadiene rubber |

| PDITC | 1,4-Phenylene diisothiocyanate |

| Nd(vers)3 | Neodymium versatate |

| DIEA | N,N-Diisopropylethylamine |

| HCl | Hydrochloric acid |

| DMAP | 4-(Dimethylamino) pyridine |

References

- Xia, Z.; Feng, Z.; Wu, R.; Niu, Z.; He, J.; Bai, C. Tough, Hydrophobic, Pressure-Resistant, and Self-Cleaning Underwater Engineering Materials Based on Copolymerization of Butadiene and Trifluoroethyl Methacrylate. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 8241–8249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Hernandez, B.; Patelis, N.; Arbe, A.; Ntetsikas, K.; Bhaumik, S.; Hadjichristidis, N.; Alegria, A.; Colmenero, J. Chain dynamics in polyisoprene stars with arms linked by dynamic covalent bonds to the central core. Soft Matter 2025, 21, 3347–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosse, J.C.; Campistron, I.; Derouet, D.; El Hamdaoui, A.; Houdayer, S.; Reyx, D.; Ritoit-Gillier, S. Chemical modifications of polydiene elastomers: A survey and some recent results. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000, 78, 1461–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, A.Z.; Stellbrink, J.; Allgaier, J.; Willner, L.; Richter, D.; Koenig, B.W.; Gondorf, M.; Willbold, S.; Fetters, L.J.; May, R.P. A New View of the Anionic Diene Polymerization Mechanism. Macromol. Symp. 2004, 215, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatzel, J.; Noack, S.; Schanzenbach, D.; Schlaad, H. Anionic polymerization of dienes in ‘green’ solvents. Polym. Int. 2020, 70, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundil, R.; Bravo, C.; Merle, N.; Zinck, P. Coordinative Chain Transfer and Chain Shuttling Polymerization. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 210–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Dong, W.; Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, L. Living polymerization of 1,3-butadiene by a Ziegler–Natta type catalyst composed of iron(III) 2-ethylhexanoate, triisobutylaluminum and diethyl phosphite. Polymer 2009, 50, 2826–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Cui, D.; Lv, K. Highly 3,4-Selective Living Polymerization of Isoprene with Rare Earth Metal Fluorenyl N-Heterocyclic Carbene Precursors. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 1983–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, G.W.; Hustad, P.D.; Reinartz, S. Catalysts for the Living Insertion Polymerization of Alkenes: Access to New Polyolefin Architectures Using Ziegler–Natta Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2236–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.; Mortreux, A.; Visseaux, M.; Zinck, P. Coordinative chain transfer polymerization. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 3836–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempe, R. How to polymerize ethylene in a highly controlled fashion? Chemistry 2007, 13, 2764–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X. Lanthanide complexes mediated coordinative chain transfer polymerization of conjugated dienes. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2018, 61, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dong, B.; Liu, H.; Guo, J.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, L.; Bai, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X. Synthesis of Block Copolymers Containing Polybutadiene Segments by Combination of Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerization, Ring-Opening Polymerization, and Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2014, 216, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, W.; Sita, L.R. Aufbaureaktion redux: Scalable production of precision hydrocarbons from AlR3 (R = Et or iBu) by dialkyl zinc mediated ternary living coordinative chain-transfer polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010, 49, 1768–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.; Zinck, P.; Mortreux, A.; Bria, M.; Visseaux, M. Half-lanthanocene/dialkylmagnesium-mediated coordinative chain transfer copolymerization of styrene and hexene. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2011, 49, 3778–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Duman, L.M.; Redman, D.W.; Yonke, B.L.; Zavalij, P.Y.; Sita, L.R. N-Substituted Iminocaprolactams as Versatile and Low Cost Ligands in Group 4 Metal Initiators for the Living Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerization of α-Olefins. Organometallics 2017, 36, 4202–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meurs, G.J.P.B.M.; Gibson, V.C.; Cohe, S.A. Polyethylene Chain Growth on Zinc Catalyzed by Olefin Polymerization Catalysts: A Comparative Investigation of Highly Active Catalyst Systems across the Transition Series. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 9913–9923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Yan, N.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Bai, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X. Highly trans-1,4-stereoselective coordination chain transfer polymerization of 1,3-butadiene and copolymerization with cyclic esters by a neodymium-based catalyst system. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 6088–6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sita, L.R. Highly Efficient, Living Coordinative Chain-Transfer Polymerization of Propene with ZnEt2: Practical Production of Ultra high to Very Low Molecular Weight Amorphous Atactic Polypropenes of Extremely Narrow Polydispersity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 442–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinck, P.; Visseaux, M.; Mortreux, A. Borohydrido Rare Earth Complexes as Precatalysts for the Polymerisation of Styrene. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2006, 632, 1943–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Dong, J.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F. Facile and efficient in-situ end-functionalization of neodymium-based polybutadiene by isocyanate via a coordinative chain transfer polymerization strategy. Polymer 2024, 305, 127166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.D.X.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Synthesis and Performance Study of High-molecular-weight Amide End-functionalized cis-Polybutadiene Rubber. Acta Polym. Sin. 2025, 56, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar]

- Baulu, N.; Langlais, M.; Ngo, R.; Thuilliez, J.; Jean-Baptiste-Dit-Dominique, F.; D’Agosto, F.; Boisson, C. Switch from Anionic Polymerization to Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerization: A Valuable Strategy to Make Olefin Block Copolymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2022, 61, e202204249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, W.; Dong, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Synthesis of Multi-hydroxyl Terminated Polybutadiene Liquid Rubber Featuring High 1,4-Content. Acta Polym. Sin. 2025, 56, 457–464. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, W.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Controllable Preparation of Hydroxyl-Terminated Liquid Polydiene Rubber Featuring High 1,4-Content by Neodymium-Mediated Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerizations Strategy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e57602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Cui, D.; Hou, Z.; Li, X. Living catalyzed-chain-growth polymerization and block copolymerization of isoprene by rare-earth metal allyl precursors bearing a constrained-geometry-conformation ligand. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 3022–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Neodymium-Mediated Coordinative Chain Transfer Homopolymerization of Bio-Based Myrcene and Copolymerization With Butadiene and Isoprene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 142, e56557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Zhang, K.; Nishiura, M.; Hou, Z. Chain-shuttling polymerization at two different scandium sites: Regio- and stereospecific “one-pot” block copolymerization of styrene, isoprene, and butadiene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 12012–12015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Yang, Q.; Dong, J.; Wang, F.; Luo, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Neodymium-based one-precatalyst/dual-cocatalyst system for chain shuttling polymerization to access cis-1,4/trans-1,4 multiblock polybutadienes. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 27, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, C.; Merle, N.; Sauthier, M.; Bria, M.; De Winter, J.; Zinck, P. Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerization of Butadiene Using Nickel(II) Allyl Systems: A Straightforward Route to Branched Polybutadiene. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 8106–8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, M.; Liu, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X. Randomly Coordinative Chain Transfer Copolymerization of 1,3-Butadiene and Isoprene: A Highly Atom-Economic Way for Accessing Butadiene/Isoprene Rubber. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 10754–10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, C.; Hu, Y.; Jia, X.; Bai, C.; Zhang, X. Reversible coordinative chain transfer polymerization of isoprene and copolymerization with ε-caprolactone by neodymium-based catalyst. Polymer 2012, 53, 6027–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Zheng, W.; Guo, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y.; Bai, C.; Zhang, X. Fully-reversible and semi-reversible coordinative chain transfer polymerizations of 1,3-butadiene with neodymium-based catalytic systems. Polymer 2013, 54, 6716–6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, L.; Cong, R.; Dong, J.; Wu, G.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. In-situ block copolymerization of 1,3-butadiene with cyclohexene oxide and trimethylene carbonate via combination of coordinative chain transfer polymerization and ring opening polymerization by neodymium-based catalyst system. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 148, 110355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natta, G. Properties of isotactic; atactic; stereoblock homopolymers, random and block copolymers of α-olefins. J. Polym. Sci. 2003, 34, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulu, N.; Poradowski, M.-N.; Verrieux, L.; Thuilliez, J.; Jean-Baptiste-Dit-Dominique, F.; Perrin, L.; D’AGosto, F.; Boisson, C. Design of selective divalent chain transfer agents for coordinative chain transfer polymerization of ethylene and its copolymerization with butadiene. Polym. Chem. 2022, 13, 1970–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alioui, S.; Langlais, M.; Ngo, R.; Habhab, K.; Dronet, S.; Jean-Baptiste-Dit-Dominique, F.; Albertini, D.; D’AGosto, F.; Boisson, C.; Montarnal, D. New Thermoplastic Elastomers based on Ethylene-Butadiene-Rubber (EBR) by Switching from Anionic to Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202420946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaid, I.; Macqueron, B.; Poradowski, M.-N.; Bouaouli, S.; Thuilliez, J.; Cruz-Boisson, F.D.; Monteil, V.; D’Agosto, F.; Perrin, L.; Boisson, C. Identification of a Transient but Key Motif in the Living Coordinative Chain Transfer Cyclocopolymerization of Ethylene with Butadiene. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 9298–9309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgranges, A.; Jean-Baptiste-Dit-Dominique, F.; Ngo, R.; D’AGosto, F.; Boisson, C. Nitriles as Functionalization and Coupling Agents for Polyolefins Obtained by Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerization. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2024, 45, e2400226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resconi, L.; Piemontesi, F.; Camurati, I.; Balboni, D. Diastereoselective Synthesis, Molecular Structure, and Solution Dynamics of meso- and rac-[Ethylenebis(4,7-dimethyl-è5-1-indenyl)]zirconium Dichloride Isomers and Chain Transfer Reactions inPropene Polymerization with the rac Isomer. Organometallics 1996, 15, 5046–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alioui, S.; Montarnal, D.; D’AGosto, F.; Boisson, C. Block copolymers from coordinative chain transfer (co)polymerization (CCT(co)P) of olefins and 1,3-dienes and mechanical properties of the resulting thermoplastic elastomers. Polym. Chem. 2025, 16, 3761–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, T.; Enriquez-Medrano, F.J.; Cartagena, E.M.; Villanueva, A.B.; Valencia, L.; Alvarez, E.N.C.; Gonzalez, R.L.; Diaz-de-Leon, R. Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerization of Sustainable Terpene Monomers Using a Neodymium-Based Catalyst System. Polymers 2022, 14, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, F.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Liu, H. Synthesis and Characterization of Terpenoid-derived Poly(6,10-dimethyl-1,3,9-undecatriene): A Biobased and Sustainable Polymer from Renewable Citronellal. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2025, 43, 1825–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña, I.; González Zapata, J.L.; Saade, H.; Córdova, T.; Castañeda Facio, A.; Díaz Elizondo, J.A.; Valencia, L.; López-González, H.R.; Díaz de León, R. Terpene-Derived Bioelastomers for Advanced Vulcanized Rubbers and High-Impact Acrylonitrile–Butadiene–Styrene. Processes 2025, 13, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Bai, C.; Cai, H.; Dai, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F. Preparation of high cis-1,4 polyisoprene with narrow molecular weight distribution via coordinative chain transfer polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 4768–4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. In Situ Efficient End Functionalization of Polyisoprene by Epoxide Compounds via Neodymium-Mediated Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerization. Polymers 2024, 16, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Tang, M.; Li, S.; Xv, Y.; Huang, G. Effects of oligopeptides end-group on properties of polyisoprenewith different molecular weights. China Synth. Rubber Ind. 2018, 41, 266–270. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.; Li, S.; Huang, G.; Xu, Y. Synthesis, Characterization and Rheological Properties of Tetrapepetide-Terminated Polyisoprene. Polym. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 33, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.-K.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Zhang, R.; Yang, Y.; Cao, J.; Tang, M.-Z.; Huang, G.; Xu, Y.-X. Carbonate nanophase guided by terminally functionalized polyisoprene leading to a super tough, recyclable and transparent rubber. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Bai, S.-J.; Xu, R.; Zhang, R.; Li, S.-Q.; Xu, Y.-X. Oligopeptide binding guided by spacer length lead to remarkably strong and stable network of polyisoprene elastomers. Polymer 2021, 233, 124185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Zhang, R.; Li, S.; Zeng, J.; Luo, M.; Xu, Y.; Huang, G. Towards a Supertough Thermoplastic Polyisoprene Elastomer Based on a Biomimic Strategy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 15836–15840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tang, M.; Huang, C.; Zhang, R.; Wu, J.; Ling, F.; Xu, Y.-X.; Huang, G. Branching function of terminal phosphate groups of polyisoprene chain. Polymer 2019, 174, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, W.; Dong, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Polyisoprene Bearing Dual Functionalized Mini-Blocky Chain-Ends Prepared from Neodymium-mediated Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerizations. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 41, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.; Wang, F.; Wei, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Synthesis of α,ω-end hetero-functionalized polyisoprene via neodymium-mediated coordinative chain transfer polymerization. Polym. Chem. 2025, 16, 1556–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hadjichristidis, N. Synthesis of alpha, omega-End Functionalized Polydienes: Allylic-Bearing Heteroleptic Aluminums for Selective Alkylation and Transalkylation in Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202317494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Zhang, J.; He, A. Synthesis of amine-capped Trans-1,4-polyisoprene. Polymer 2021, 235, 124231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georges, S.; Hashmi, O.H.; Bria, M.; Zinck, P.; Champouret, Y.; Visseaux, M. Efficient One-Pot Synthesis of End-Functionalized trans-Stereoregular Polydiene Macromonomers. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leicht, H.; Bauer, J.; Göttker-Schnetmann, I.; Mecking, S. Heterotelechelic and In-Chain Polar Functionalized Stereoregular Poly(dienes). Macromolecules 2018, 51, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G. End-modification in course of Polymerization of Butadiene Intiated by Rare Earth Catalyst. Spec. Petrochem. 2012, 29, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Leicht, H.; Gottker-Schnetmann, I.; Mecking, S. Stereoselective Copolymerization of Butadiene and Functionalized 1,3-Dienes. ACS Macro Lett. 2016, 5, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottker-Schnetmann, I.; Kenyon, P.; Mecking, S. Coordinative Chain Transfer Polymerization of Butadiene with Functionalized Aluminum Reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 17777–17781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhu, H.; Huang, X.; Wu, Y. Amphiphilic Silicon Hydroxyl-Functionalized cis-Polybutadiene: Synthesis, Characterization, and Properties. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 2427–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, J.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Efficient in-situ end-functionalization of polydienes by isothiocyanate vianeodymium mediated coordinative chain transfer polymerization system. China Synth. Rubber Ind. 2024, 47, 347. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Xu, Y. New Insights into the Strengthening Mechanism of Nanofillers in Terminally Functionalized Polyisoprene Rubbers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 4073–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Run | [IP]/[Nd] | Mn(obs) g/mol | Mw/Mn | Mn (cal) a g/mol | Mn (cal) b g/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 1200 | 1.14 | 6800 | 900 |

| 2 | 200 | 2000 | 1.21 | 13,600 | 1800 |

| 3 | 300 | 3000 | 1.23 | 20,400 | 2700 |

| 4 | 400 | 4000 | 1.20 | 27,200 | 3600 |

| 5 | 800 | 7400 | 1.24 | 54,400 | 7100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Zhao, W.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. End-Functionalization in Coordination Chain Transfer Polymerization of Conjugated Dienes. Catalysts 2026, 16, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020121

Liu L, Zhao W, Wang F, Zhang X, Liu H. End-Functionalization in Coordination Chain Transfer Polymerization of Conjugated Dienes. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020121

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Lijia, Wenpeng Zhao, Feng Wang, Xuequan Zhang, and Heng Liu. 2026. "End-Functionalization in Coordination Chain Transfer Polymerization of Conjugated Dienes" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020121

APA StyleLiu, L., Zhao, W., Wang, F., Zhang, X., & Liu, H. (2026). End-Functionalization in Coordination Chain Transfer Polymerization of Conjugated Dienes. Catalysts, 16(2), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020121