Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of 1,4-Dihydropyridines via the Hantzsch Reaction Using a Recyclable HPW/PEG-400 Catalytic System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

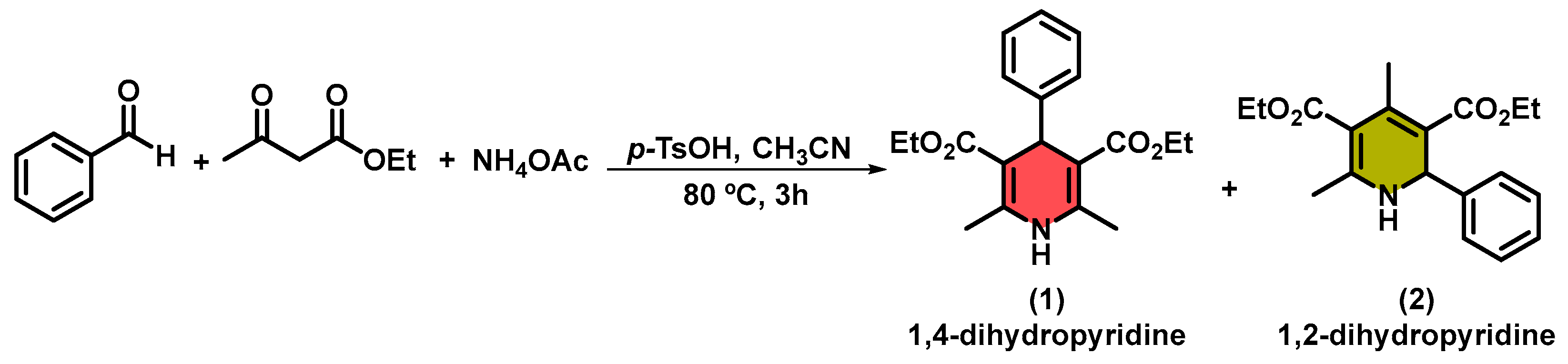

3.1. General Synthesis of 1,4-Dihydropyridines in Acetonitrile Using TsOH

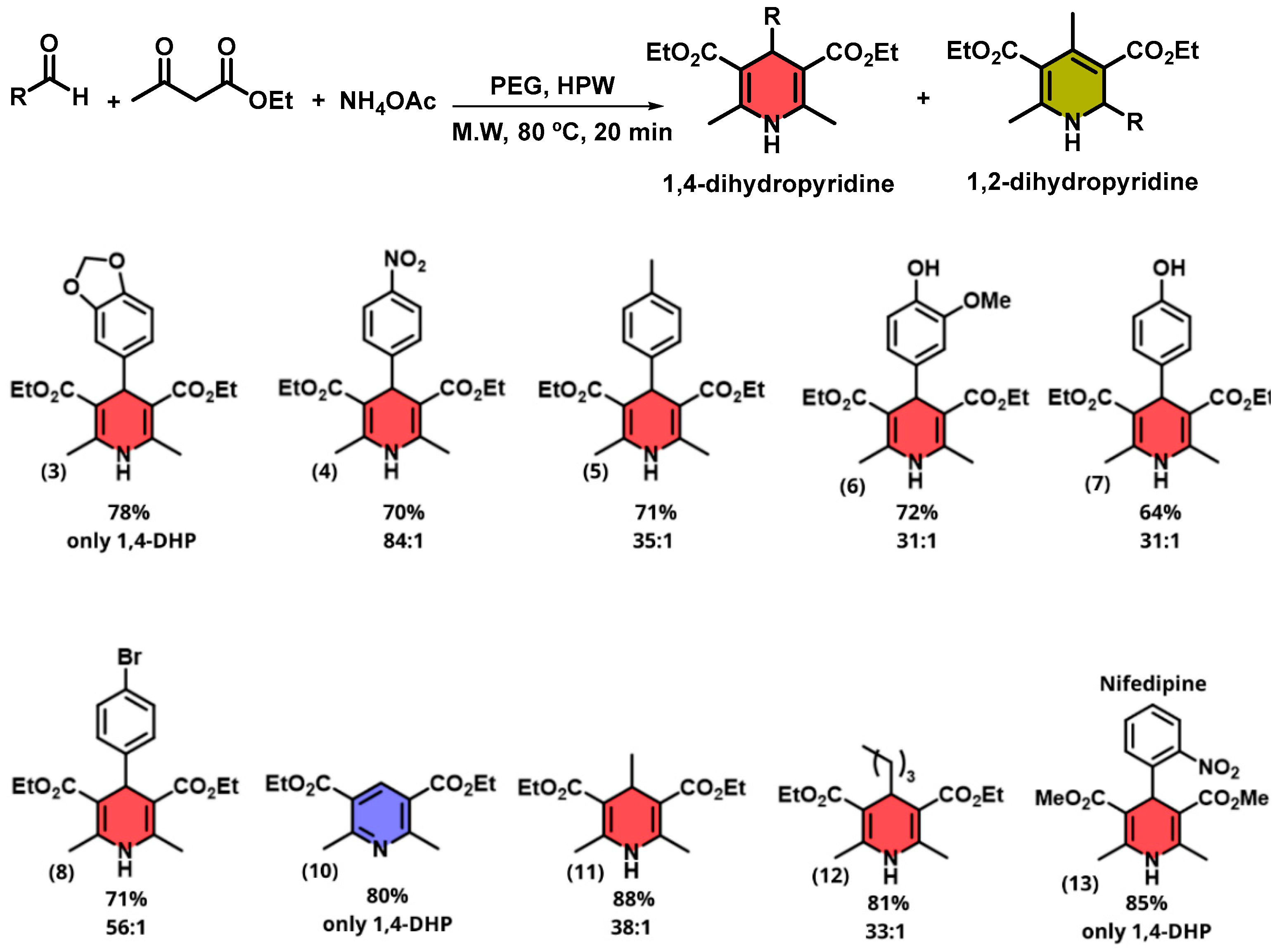

3.2. General Synthesis of 1,4-Synthesis in PEG-400 Using HPW

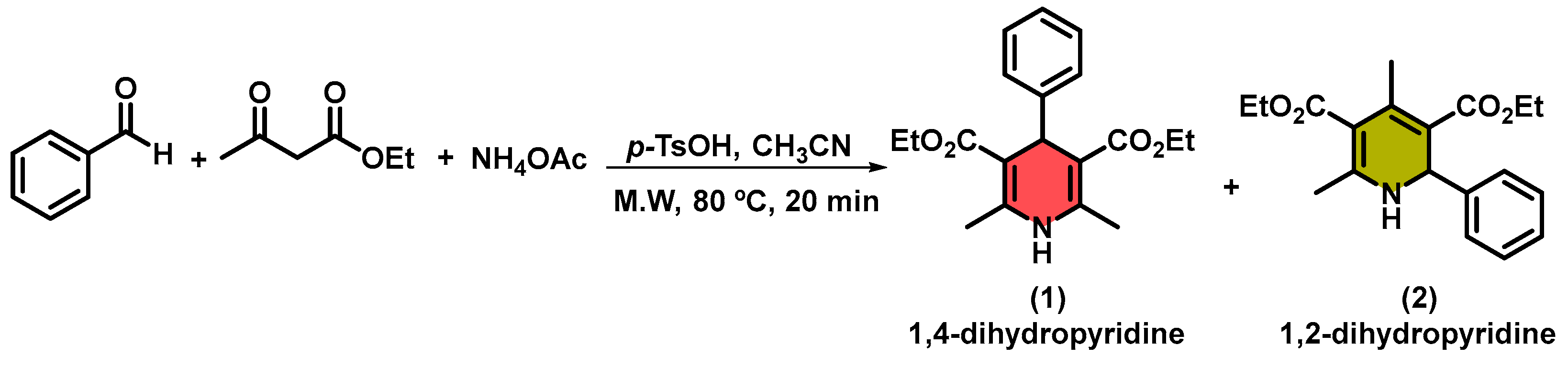

3.3. General Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of 1,4-Dihydropyridines in Acetonitrile Using TsOH

3.4. General Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of 1,4-Dihydropyridines in PEG-400 Using HPW

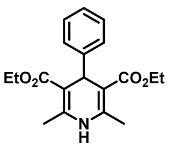

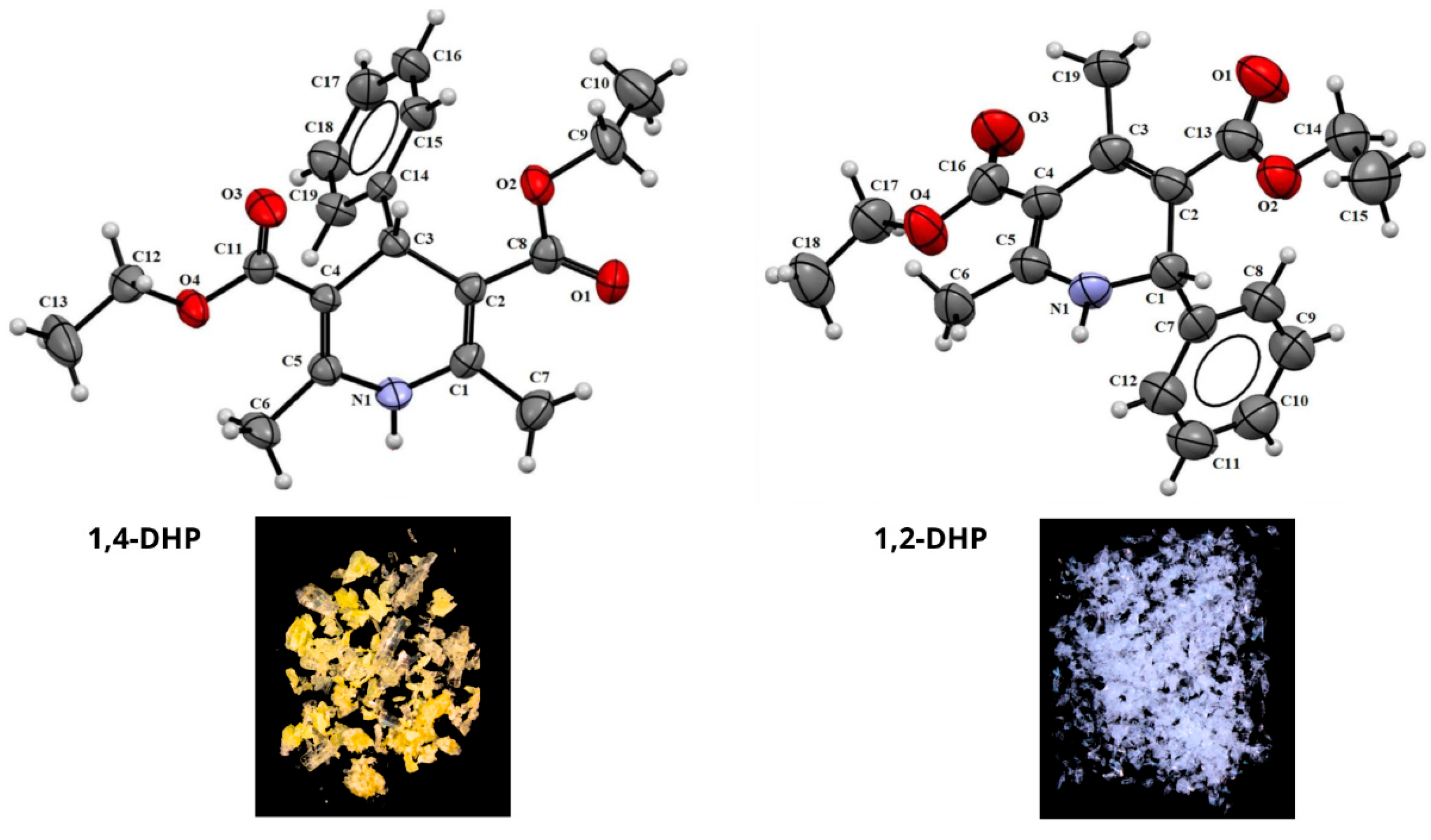

| Diethyl 2,6-dimethyl-4-phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (1) [38]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.27 (d, J = 7.70 Hz, 2H), 7.20 (t, J = 7.66 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (t, J = 7.50 Hz, 1H), 5.78 (s, 1H), 4.99 (s, 1H), 4.04–4.13 (m, 4H), 2.31 (s, 6H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.11 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.7, 147.8, 143.9, 128.0, 127.8, 126.1, 104.1, 59.7, 39.6, 19.5, 14.2. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z calculated for C19H24NO4+ [M + H]+: 330.1627; found [M + H]+: 330.1626. mp: 155–157 °C (yellow solid). |

| Diethyl 2,4-dimethyl-6-phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (2) [35]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.24–7.30 (m, 5H), 5.61 (d, J = 4.05 Hz, 1H), 5.41 (d, J = 4.05 Hz, 1H), 4.08–4.25 (m, 2H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 2.22 (s, 3H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.13 Hz, 3H), 1.21 (t, J = 7.13 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3). HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z calculated for C19H24NO4+ [M + H]+: 330.1627; found [M + H]+: 330.1626. mp: 145–146 °C (white solid). |

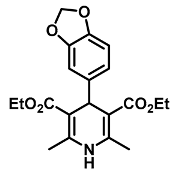

| Diethyl 4-(benzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2,6-dimethyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (3) [47]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.78 (d, J = 1.65 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (dd, J = 8.00, 1.65 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 7.99 Hz, 1H), 5.87 (s, 2H), 5.73 (s, 1H), 4.92 (s, 1H), 4.06–4.15 (m, 4H), 2.31 (s, 6H), 1.24 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.6, 147.2, 145.7, 143.7, 142.0, 120.9, 108.6, 107.5, 104.3, 100.6, 59.7, 39.3, 19.6, 14.3. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z calculated for C20H24NO6+ [M + H]+: 374.1525; found [M + H]+: 374.1526. mp: 198–200 °C (yellow solid). |

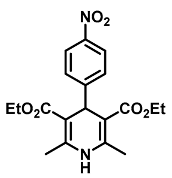

| Diethyl 2,6-dimethyl-4-(4-nitrophenyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (4) [38]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.10 (d, J = 8.80 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.90 Hz, 2H), 5.78 (s, 1H), 5.11 (s, 1H), 4.07–4.15 (m, 4H), 2.38 (s, 6H), 1.24 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.0, 155.1, 146.4, 144.6, 128.9, 123.3, 103.2, 60.0, 40.1, 19.7, 14.3. HRMS (ESI-QTOF) m/z calculated for C19H23N2O6+ [M + H]+: 375.1478; found [M + H]+: 375.1477. mp: 194–196 °C (yellow solid). |

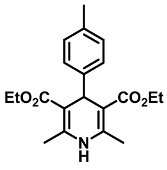

| Diethyl 2,6-dimethyl-4-(p-tolyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (5) [38]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.19 (d, J = 7.87 Hz, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 7.85 Hz, 2H), 5.78 (s, 1H), 4.97 (s, 1H), 4.08–4.15 (m, 4H), 2.34 (s, 6H), 2.29 (s, 3H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.14 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.7, 144.9, 143.8, 135.5, 128.6, 127.8, 127.7, 104.2, 60.4, 59.7, 39.1, 21.0, 19.6, 14.3. HRMS (ESI-QTOF) m/z calculated for C20H26NO4+ [M + H]+: 344.1784; found [M + H]+: 344.1784. (Yellow pasty solid). |

| Diethyl 4-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2,6-dimethyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (6) [48]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.95 (d, J = 8.31 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 1.72 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (dd, J = 8.30, 1.72 Hz, 1H), 5.69 (s, 1H), 5.50 (s, 1H), 4.94 (s, 1H), 4.09–4.16 (m, 4H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 2.35 (s, 6H), 1.26 (t, J = 7.11 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.7, 145.8, 143.9, 143.6, 140.1, 120.5, 113.9, 110.9, 104.3, 59.7, 55.8, 39.1, 19.6, 14.3. C20H26NO6+ [M + H]+: 376.1682; found [M + H]+: 376.1682. mp: 161–163 °C (yellow solid). |

| Diethyl 4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2,6-dimethyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (7) [38]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.15 (d, J = 8.39 Hz, 2H), 6.68 (d, J = 8.44 Hz, 2H), 5.62 (s, 1H), 4.94 (s, 1H), 4.08–4.17 (m, 4H), 2.34 (s, 6H), 1.24 (t, J = 7.11 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.9, 154.0, 143.6, 140.2, 129.2, 114.7, 104.5, 59.8, 38.8, 19.6, 14.3. C19H24NO5+ [M + H]+: 346.1576 found [M + H]+: 346.1576. mp: 238–240 °C (yellow solid). |

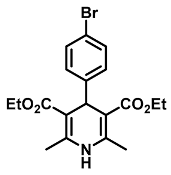

| Diethyl 4-(4-bromophenyl)-2,6-dimethyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (8) [38]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.34 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H), 7.18 (d, J = 8.42 Hz, 2H), 5.80 (s, 1H), 4.97 (s, 1H), 4.07–4.14 (m, 4H), 2.34 (s, 6H), 1.24 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.4, 146.9, 143.6, 144.1, 130.9, 129.9, 119.9, 103.8, 59.8, 39.3, 19.6, 14.3. HRMS (ESI-QTOF) m/z calculated for C19H23BrNO4+ [M + H]+: 408.0732; found [M + H]+: 408.0734. mp: 241–243 °C (orange solid). |

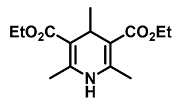

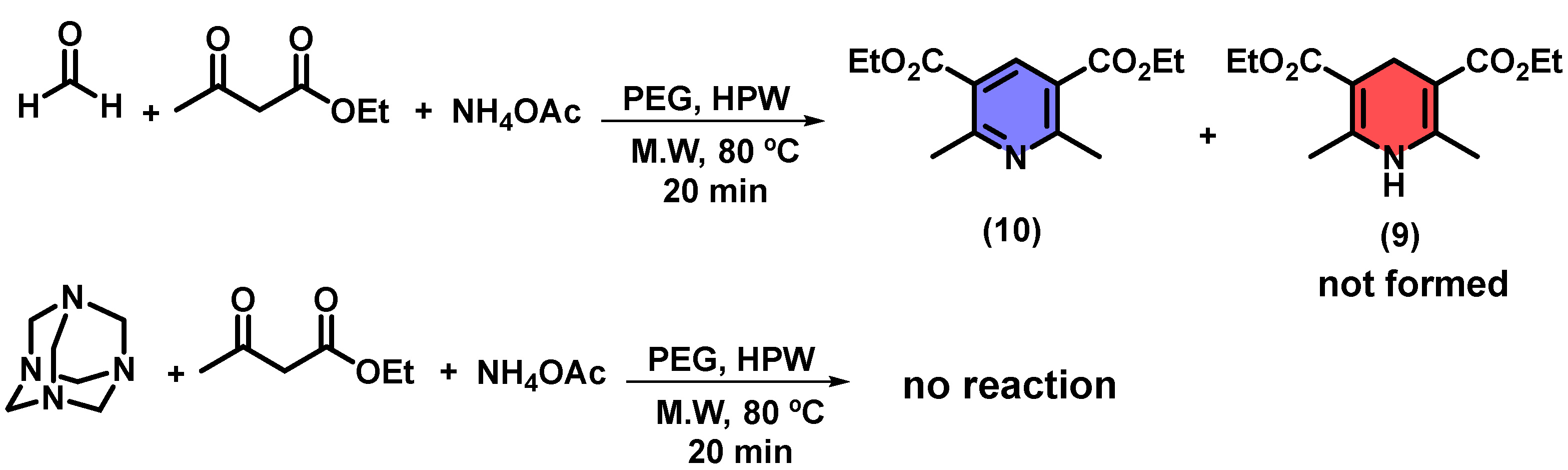

| Diethyl 2,6-dimethyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (9) [41]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.16 (q, J = 7.12 Hz, 4H), 3.26 (s, 2H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 1.28 (t, J = 7.14 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.1, 144.9, 99.5, 59.7, 24.8, 19.2, 14.5. HRMS (ESI-QTOF) m/z calculated for C13H20NO4+ [M + H]+: 254.1314; found [M + H]+: 254.1313. mp: 179–182 °C (yellow solid). |

| Diethyl 2,6-dimethylpyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (10) [41]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.70 (s, 1H), 4.41 (q, J = 7.14 Hz, 4H), 2.87 (s, 6H), 1.43 (t, J = 7.16 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.9, 162.2, 140.9, 123.1, 61.4, 24.9, 14.3. HRMS (ESI-QTOF) m/z calculated for C13H18NO4+ [M + H]+: 252.1158; found [M + H]+: 252.1159. mp: 70–73 °C (yellow solid). |

| Diethyl 2,4,6-trimethyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (11) [49]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.67 (m, 4H), 3.74 (q, J = 7.14 Hz, 1H), 2.08 (s, 6H), 1.57 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 6H), 0.91 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.6, 147.7, 104.1, 59.7, 27.6, 23.4, 19.5, 14.2. HRMS (ESI-QTOF) m/z calculated for C14H22NO4+ [M + H]+: 268.1471; found [M + H]+: 268.1470. mp: 131–132 °C (yellow solid). |

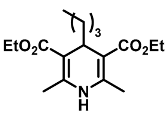

| Diethyl 4-isobutyl-2,6-dimethyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (12): | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.17 (q, J = 7.15 Hz, 4H), 3.24 (t, J = 7.11 Hz, 1H), 2.19 (s, 6H), 1.60-1.57 (m, 6H), 1.55-1.40 (m, 6H), 1.38 (t, J = 7.14 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.1, 144.9, 99.5, 59.7, 36.3,32.1, 27.3, 24.8, 19.2, 14.5. HRMS (ESI-QTOF) m/z calculated for C17H26NO4+ [M + H]+: 308.1784; found [M + H]+: 308.1783. mp: 155–157 °C (yellow solid). |

| Dimethyl 2,6-dimethyl-4-(2-nitrophenyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate-Nifedipine (13) [41]: | |

| 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.85 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.78-7.62 (m, 3H), 5.77 (s,1H), 5.09 (s, 1H), 3.69 (s, 6H); 2.35 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.1, 146.4, 144.6, 141.0, 133.4, 130.1, 128.9, 123.3, 103.2, 60.0, 40.1, 19.70 HRMS (ESI-QTOF) m/z calculated for C13H18NO4+ [M + H]+: 347.1165; found [M + H]+: 347.1165. mp: 171–173 °C (yellow solid). |

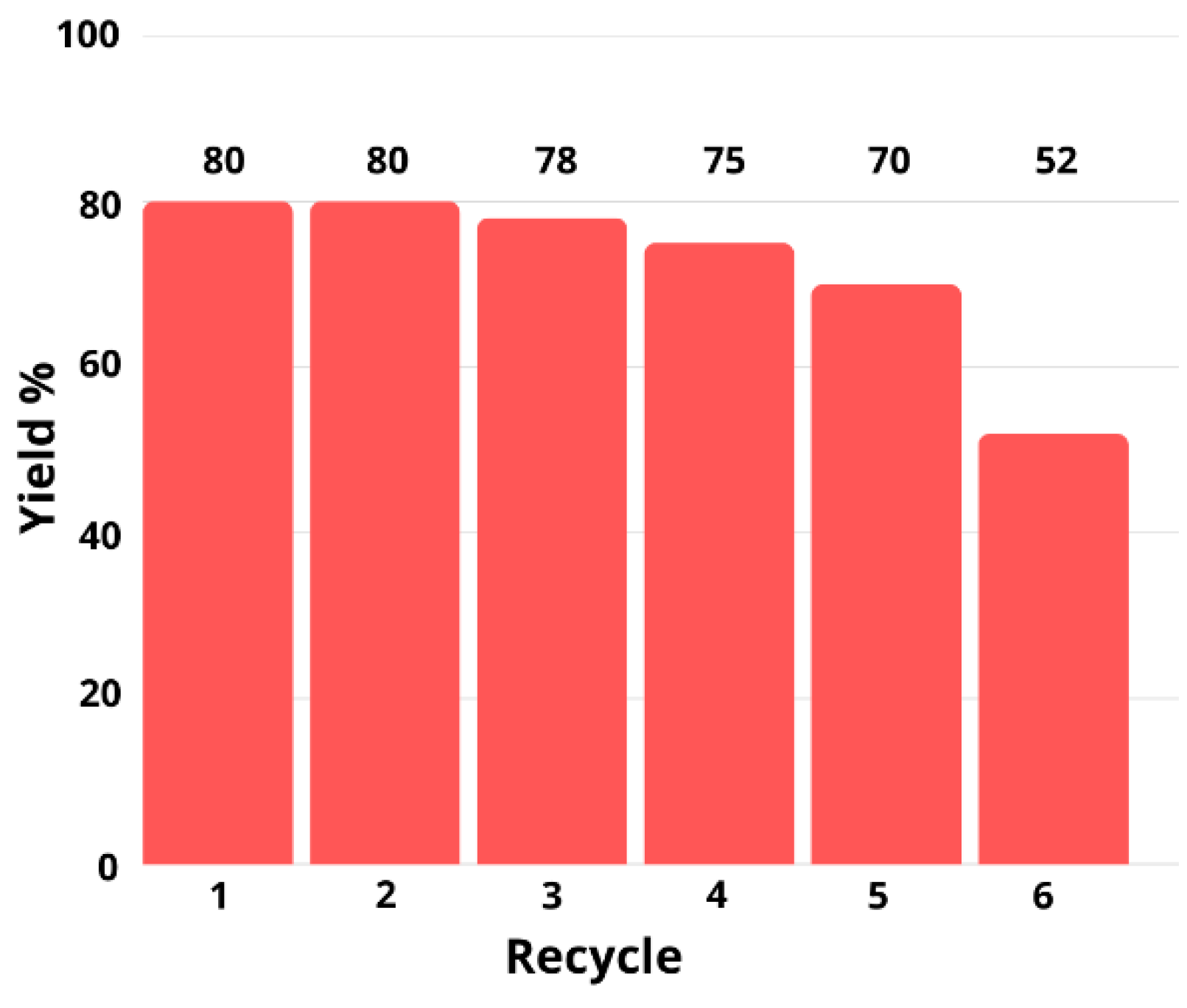

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DHP’s | Dihydropyridines |

| HPW | Phosphotungstic acid |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| p-TsOH | p-toluenesulfonic acid |

| NADH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| IUPAC | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry |

| CCBs | Calcium-channel blockers |

| MCR | Multicomponent reaction |

| ([Msim]Cl) | 3-methyl-1-sulfonic acid imidazolium chloride |

| MW | Microwave |

| 1HNMR | proton nuclear magnetic resonance |

| 13CNMR | Carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance |

| MAOS | microwave-assisted organic synthesis |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| ORTEP | Oak Ridge Thermal Ellipsoid Plot |

| TLC | Thin-layer chromatography |

| HRMS (ESI-QTOF) | high-resolution mass spectrometry performed using electrospray ionization–quadrupole time-of-flight |

References

- Khan, E. Pyridine derivatives as biologically active precursors: Organics and selected coordination complexes. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 3041–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, D.; Sreekanth, P.S.R.; Behera, P.K.; Pradhan, M.K.; Patnaik, A.; Salunkhe, S.; Cep, R. Advances in synthesis, medicinal properties and biomedical applications of pyridine derivatives: A comprehensive review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2024, 12, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Kumari, A.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, S.; Singh, R.K. Progress in nitrogen and oxygen-based heterocyclic compounds for their anticancer activity: An update (2017–2020). In Key Heterocyclic Cores for Smart Anticancer Drug-Design Part I; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2022; pp. 232–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerru, N.; Gummidi, L.; Maddila, S.; Gangu, K.K.; Jonnalagadda, S.B. A review on recent advances in nitrogen-containing molecules and their biological applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R.; Negi, K.S.; Shrivastava, R.; Nair, R. Recent developments in the nanomaterial-catalyzed green synthesis of structurally diverse 1,4-dihydropyridines. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 1376–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samrat, A.K.; Pratibha, B.A. 1,4-Dihydropyridines: A class of pharmacologically important molecules. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, A.R. An alkaloid of Dioscorea hispida, Dennst. Nature 1951, 168, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

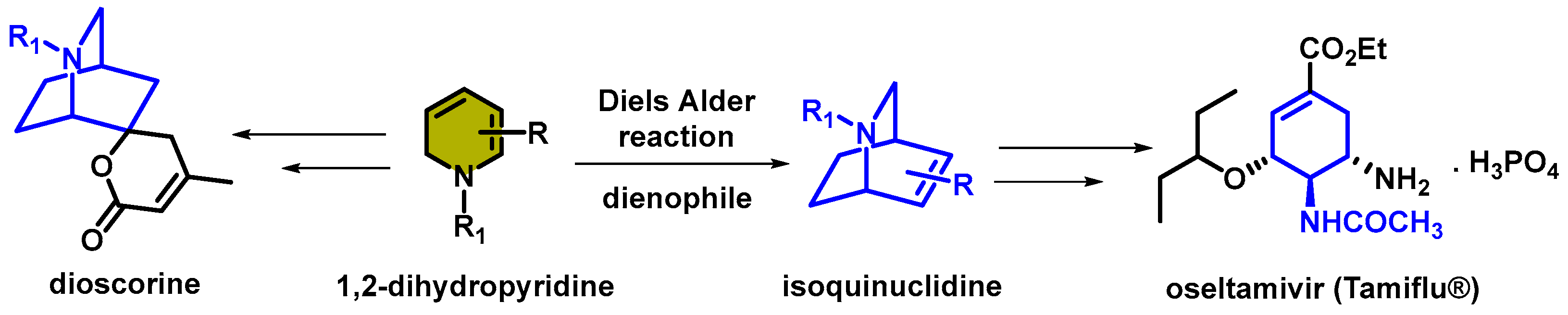

- Lavilla, R. Recent developments in the chemistry of dihydropyridines. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 2002, 9, 1141–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, H.; Osone, K.; Takeshita, M.; Kwon, E.; Seki, C.; Matsuyama, H.; Takano, N.; Kohari, Y. A novel chiral oxazolidine organocatalyst for the synthesis of an oseltamivir intermediate using a highly enantioselective Diels–Alder reaction of 1,2-dihydropyridine. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 4827–4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

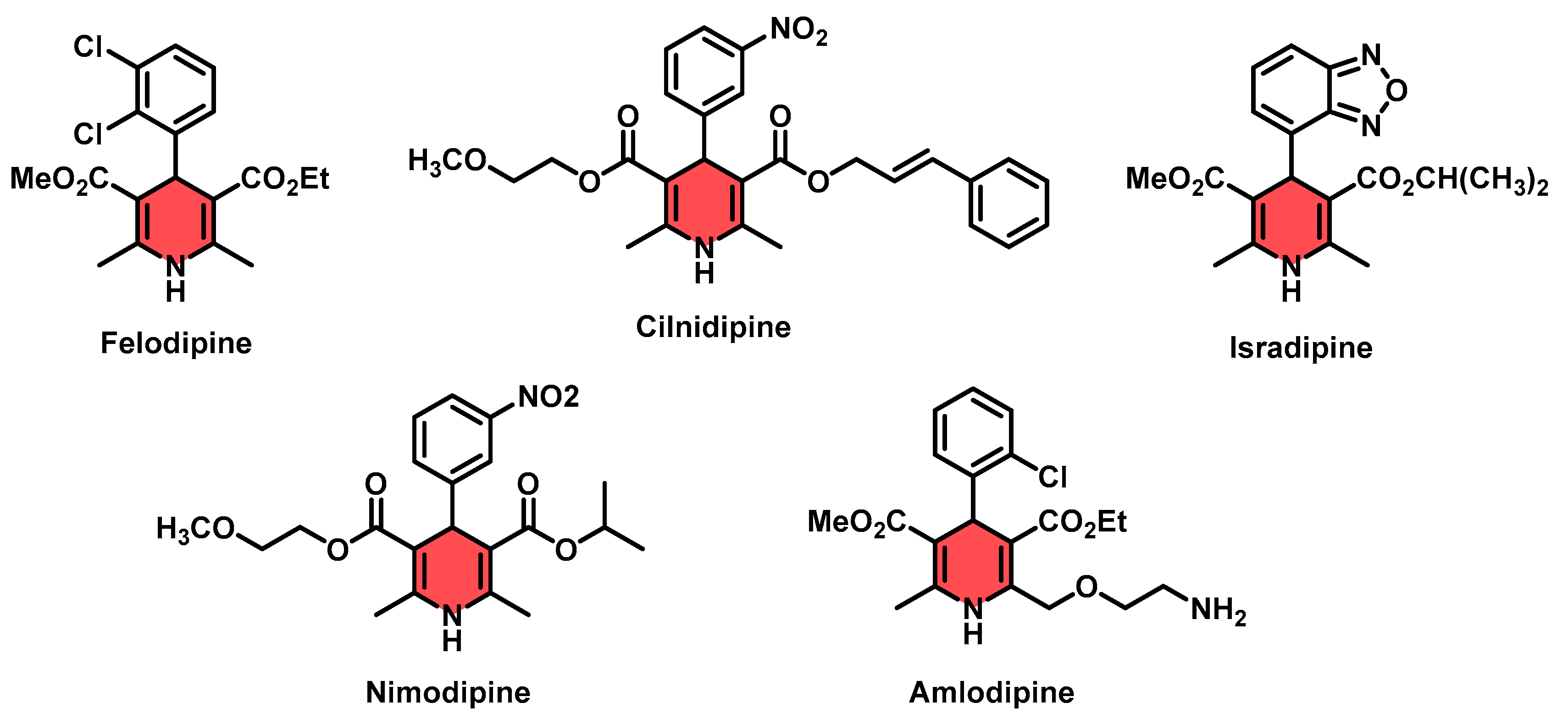

- Triggle, D.J. Calcium channel antagonists: Clinical uses—Past, present and future. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007, 74, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, D.S.; Kaur, N.; Kaur, M.; Han, H.; Bhowmik, P.K.; Husain, F.M.; Sohal, H.S.; Verma, M. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of chalcone-derived 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives using magnetic Fe2O3@SiO2 as highly efficient nanocatalyst. Catalysts 2025, 15, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brūvere, I.; Bisenieks, E.; Poikans, J.; Uldrikis, J.; Plotniece, A.; Pajuste, K.; Rucins, M.; Vīģante, B.; Kalme, Z.; Gosteva, M.; et al. Dihydropyridine derivatives as cell growth modulators in vitro. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 4069839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, H.; Kanaoka, Y. Chemical identification of binding sites for calcium channel antagonists. Heterocycles 1996, 42, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambongi, Y.; Nitta, H.; Ichihashi, K.; Futai, M.; Ueda, I. A novel water-soluble Hantzsch 1,4-dihydropyridine compound that functions in biological processes through NADH regeneration. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 3499–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, N.; Dölle, C.; Ziegler, M. The power to reduce: Pyridine nucleotides—Small molecules with a multitude of functions. Biochem. J. 2007, 402, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsch, M.E.; Snyder, S.A.; Stockwell, B.R. Privileged scaffolds for library design and drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, S.; Jain, S.; Pratap, A. A review on synthesis and biological potential of dihydropyridines. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2024, 21, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedinak, K.C.; Lopez, L.M. Felodipine: A new dihydropyridine calcium-channel antagonist. Ann. Pharmacother. 1991, 25, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, G.S.; Ahn, H.S.; Preziosi, T.J.; Battye, R.; Boone, S.C.; Chou, S.N.; Kelly, D.L.; Weir, B.K.; Crabbe, R.A.; Lavik, P.J.; et al. Cerebral Arterial Spasm—A Controlled Trial of Nimodipine in Patients with Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983, 308, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzar, A.; Sic, A.; Banh, C.; Knezevic, N.N. Therapeutic potential of calcium channel blockers in neuropsychiatric, endocrine and pain disorders. Cells 2025, 14, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, D.R.; Schwartz, J.B. Calcium-antagonist drugs. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, H.; Nakagami, H.; Yasumasa, N.; Osako, K.M.; Kyutoku, M.; Koriyama, H.; Nakagami, F.; Shimamura, M.; Rakugi, H.; Morishita, R. Cilnidipine, but not amlodipine, ameliorates osteoporosis in ovariectomized hypertensive rats through inhibition of the N-type calcium channel. Hypertens. Res. 2012, 35, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

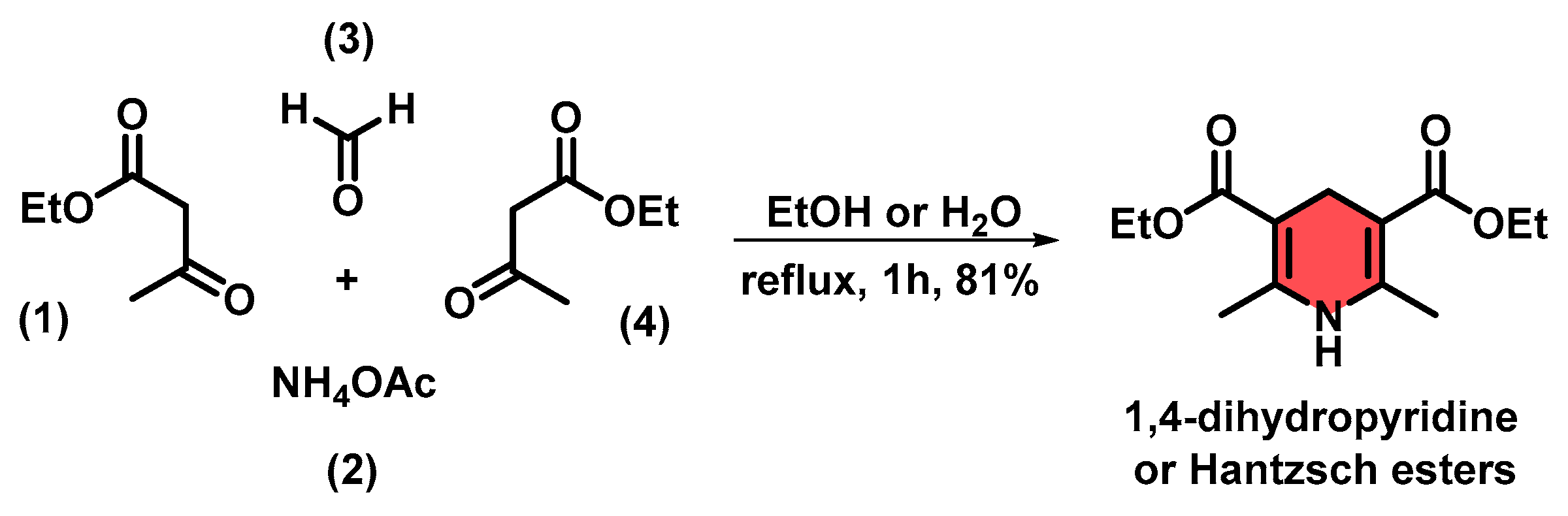

- Hantzsch, A. Condensation produkte aus Aldehydammoniak und ketonartigen Verbindungen. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1882, 215, 1–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

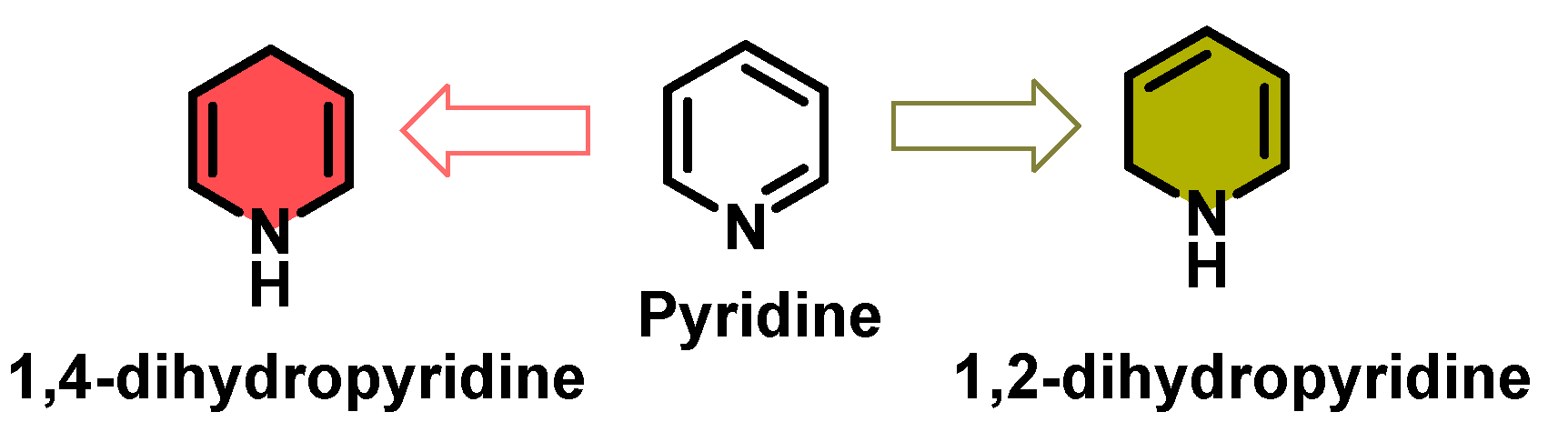

- Li, P.; Wang, S.; Tian, N.; Yan, H.; Wang, J.; Song, X. Studies on chemoselective synthesis of 1,4- and 1,2-dihydropyridine derivatives by a Hantzsch-like reaction: A combined experimental and DFT study. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 1059–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Cao, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Liu, N.; Qian, X. A revisit to the Hantzsch reaction: Unexpected products beyond 1,4-dihydropyridines. Green Chem. 2009, 11, 1414–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Siddiqui, Z.N. An efficient, green and solvent-free protocol for one-pot synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives using a new recyclable heterogeneous catalyst. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1288, 135758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A.; Kaur, N.; Kaur, M.; Singh, K.; Sohal, H.S.; Han, H.; Bhowmik, P.K. Facile one-pot synthesis and anti-microbial activity of novel 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives in aqueous micellar solution under microwave irradiation. Molecules 2024, 29, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safari, J.; Zarnegar, Z.; Mansouri-Kafroudi, Z. USY-zeolite catalyzed synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyridines under microwave irradiation: Structure and recycling of the catalyst. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1227, 129430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

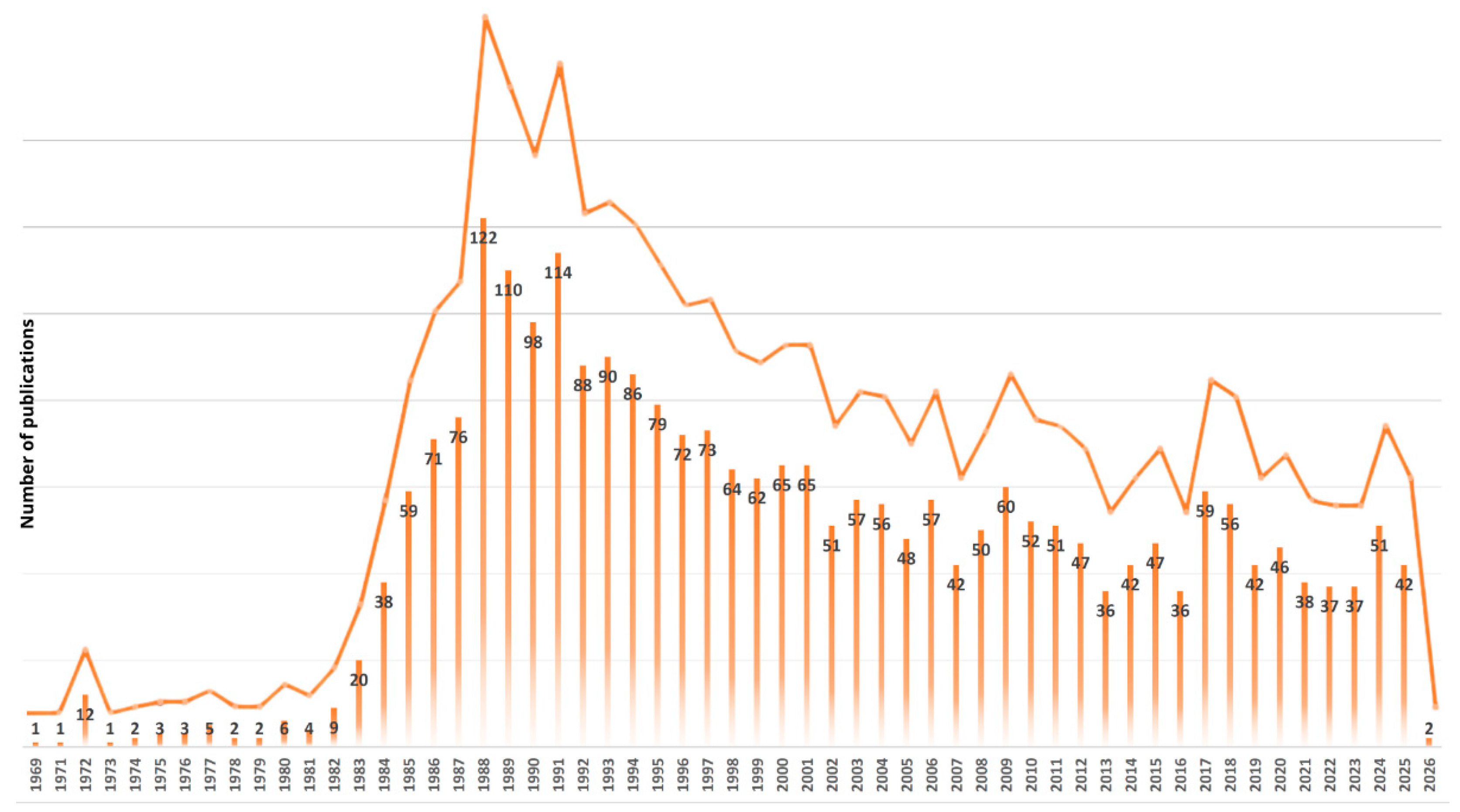

- Soni, A.; Sharma, M.; Singh, R.K. A Decade of Catalytic Progress in 1,4-Dihydropyridines (1,4-DHPs) Synthesis (2016–2024). Curr. Org. Synth. 2025, 22, 703–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Horn, A.; Khatri, H.; Sereda, G. The solvent-free synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyridines under ultrasound irradiation without catalyst. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008, 15, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Jain, S.; Pratap, A. 1,4-Dihydropyridine: Synthetic advances, medicinal and insecticidal properties. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 29253–29290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

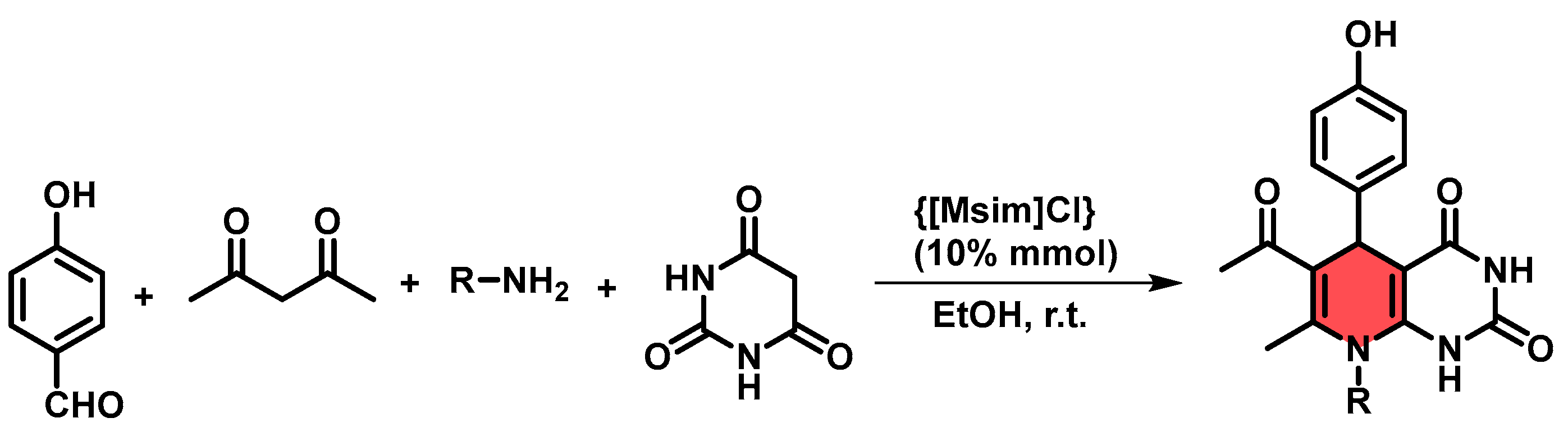

- Alvim, H.G.O.; Bataglion, G.A.; Ramos, L.M.; de Oliveira, A.L.; de Oliveira, H.C.B.; Eberlin, M.N.; de Macedo, J.L.; da Silva, W.A.; Neto, B.A.D. Task-specific ionic liquid incorporating anionic heteropolyacid-catalyzed Hantzsch and Mannich multicomponent reactions: Ionic liquid effect probed by ESI-MS(/MS). Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 3306–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez-Barbadillo, C.; González, J.F.; Porcheddu, A.; Virieux, D.; Menéndez, J.C.; Colacino, E. Benign synthesis of therapeutic agents: Domino synthesis of unsymmetrical 1,4-diaryl-1,4-dihydropyridines in the ball mill. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2022, 15, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

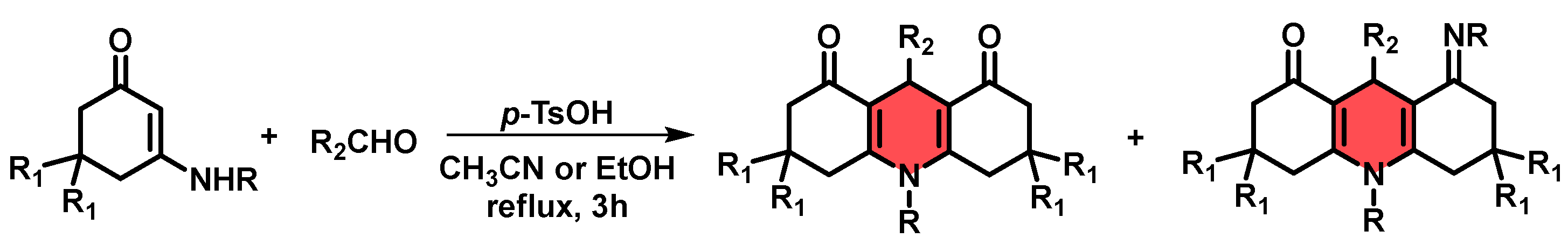

- Liu, F.-J.; Sun, T.-T.; Yang, Y.-G.; Huang, C.; Chen, X.-B. Divergent synthesis of dual 1,4-dihydropyridines with different substituted patterns from enaminones and aldehydes through domino reactions. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 12635–12643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosica, G.; Demanuele, K.; Padrón, J.M.; Puerta, A. One-pot multicomponent green Hantzsch synthesis of 1,2-dihydropyridine derivatives with antiproliferative activity. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020, 16, 2869–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, S.K.; Shivhare, K.N.; Patel, M.K.; Yadav, V.; Nazeef, M.; Siddiqui, I.R. A metal-free Hantzsch synthesis for the privileged scaffold 1,4-dihydropyridines: A glycerol-promoted sustainable protocol. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2020, 40, 1035–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassem, A.M.; Almashal, F.A.K.; Mohammed, M.Q.; Jabir, H.A.S. A catalytic and green method for one-pot synthesis of new Hantzsch 1,4-dihydropyridines. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

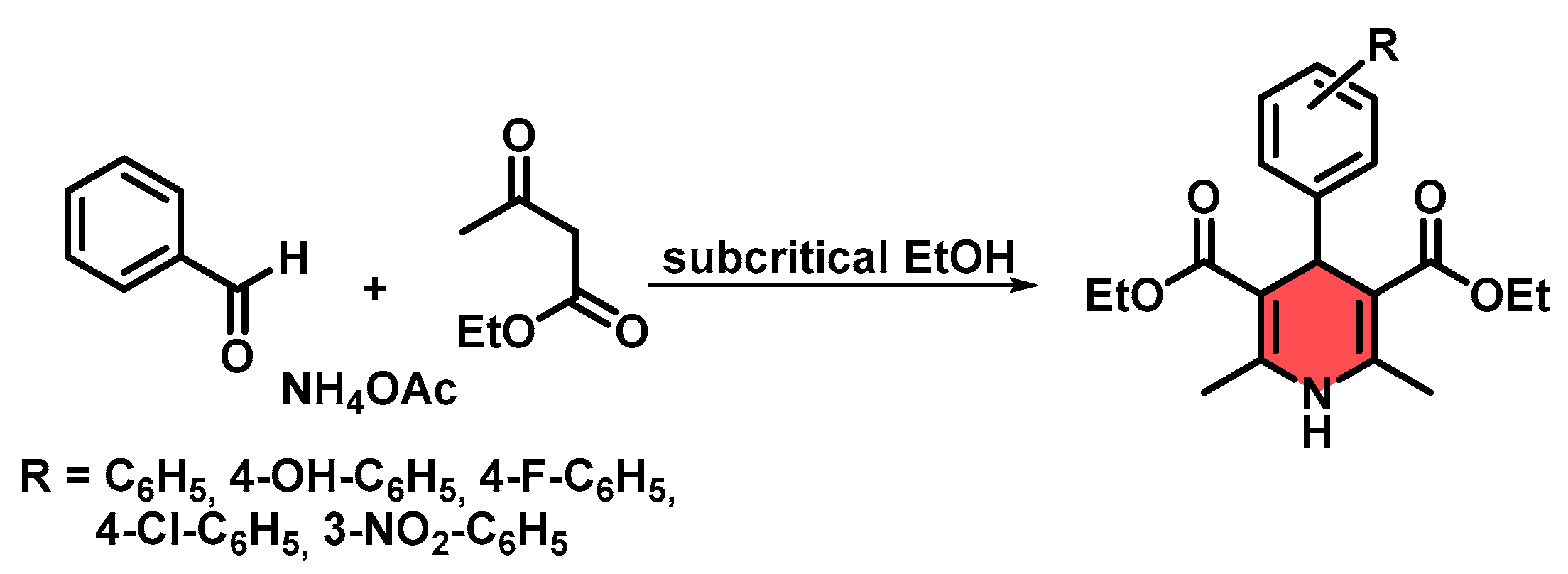

- Erşatır, M.; Türk, M.; Giray, E.S. An efficient and green synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives through multicomponent reaction in subcritical ethanol. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2021, 176, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

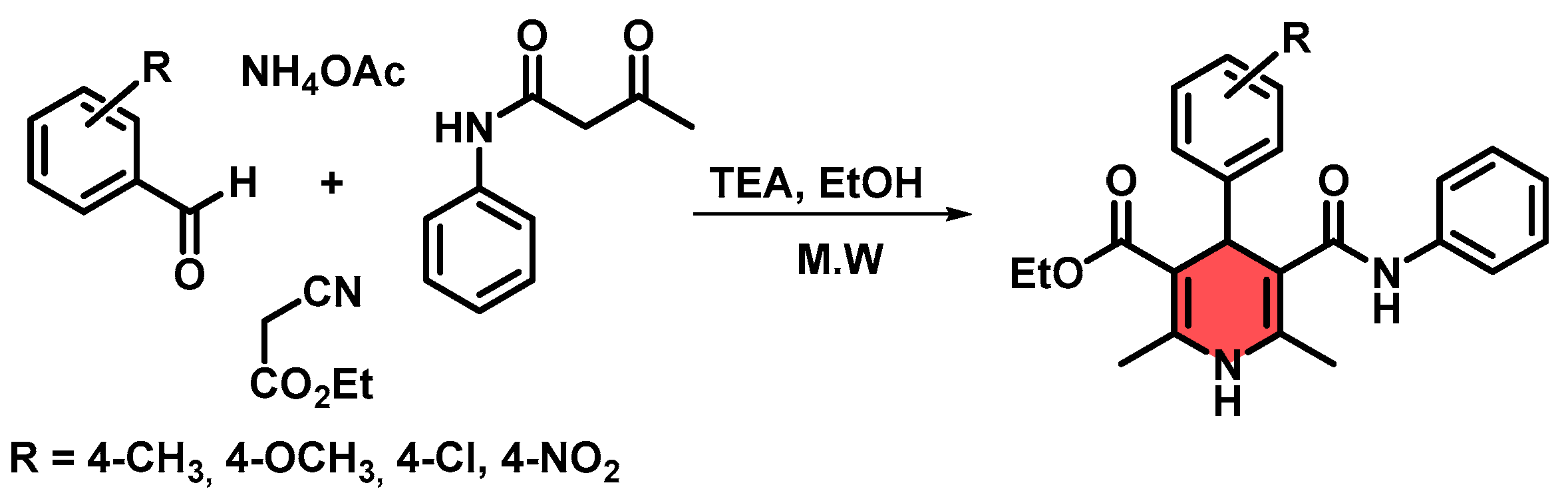

- Pachipulusu, S.; Merugu, K.S.; Bhonsle, R.R.; Kurnool, A.A. A facile microwave-mediated method of 1,4-dihydropyridine carboxylates synthesis by multicomponent reaction. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2024, 61, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.A.; Takada, S.C.S.; Nogueira, F.M.; Almeida, L.A.R. Microwave-assisted catalytic transfer hydrogenation of chalcones: A green, fast, and efficient one-step reduction using ammonium formate and Pd/C. Organics 2025, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.E.T.; Villavicencio, C.B.; Cervantes, X.L.G.; Canchingre, M.E.; Pedroso, M.T.C. Oxidative aromatization of some 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives using pyritic ash in eco-sustainable conditions. Chem. Proc. 2023, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SADABS: Program for Empirical Absorption Correction of Area Detector Data; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: From visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanthi, G.; Prasad, K.V.S.R.G.; Bharathi, K. Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of Dialkyl 4-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-6-yl)-1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-1-substituted Pyridine-3,5-dicarboxylates as Potential Anticonvulsants and Their Molecular Properties Prediction. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 66, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, R.; Navarrete-Encina, P.A.; Camargo, C.; Squella, J.A.; Núñez-Vergara, L.J. Electrochemical Oxidation of C4-Vanillin- and C4-Isovanillin-1,4-dihydropyridines in Aprotic Medium: Reactivity towards Free Radicals. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2008, 622, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loev, B.; Snader, K.M. The Hantzsch Reaction. I. Oxidative Dealkylation of Certain Dihydropyridines. J. Org. Chem. 1965, 30, 1914–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | R | Ratio 1,4-DHP:1,2-DHP a | Yield% b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | 1.1:1 | 9 |

| 2 |  | 2:1 | 15 |

| 3 |  | 2:1 | 11 |

| 4 |  | 1.2:1 | 13 |

| 5 |  | 2:1 | 10 |

| 6 |  | 4:1 | 21 |

| 7 | H | 2:1 | 30 |

| Entry | mol% Catalyst | Ratio (1,4-DHP:1,2-DHP) a | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 35:1 | 72 |

| 2 | 20 | 35:1 | 74 |

| 3 | 10 | 38:1 | 75 |

| 4 | 5 | 38:1 | 75 |

| 5 | 1 | 8:1 | 47 |

| Entry | Time (min.) | Solvent | Catalyst | Temp. (°C) | Ratio (1,4-DHP:1,2-DHP) a | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | PEG-400 | HPW | 80 | 33:1 | 71 |

| 2 | 20 | PEG-400 | HPW | 80 | 38:1 | 80 |

| 3 | 30 | PEG-400 | HPW | 80 | 33:1 | 75 |

| 4 | 40 | PEG-400 | HPW | 80 | 33:1 | 53 |

| 5 | 60 | PEG-400 | HPW | 80 | 33:1 | 51 |

| 6 | 20 | Solvent-free | HPW | 80 | - | - |

| 7 | 20 | PEG-400 | Catalyst-free | 80 | - | - |

| 8 | 20 | PEG-400 | HPW | 60 | 20:1 | 60 |

| 9 | 20 | PEG-400 | HPW | 100 | 55:1 | 52 |

| 10 | 10 | PEG-400 | HPW | 150 | 40:1 | 45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Silva, W.A.; Takada, S.C.S.; Gatto, C.C.; Maravalho, I.V. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of 1,4-Dihydropyridines via the Hantzsch Reaction Using a Recyclable HPW/PEG-400 Catalytic System. Catalysts 2026, 16, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010096

Silva WA, Takada SCS, Gatto CC, Maravalho IV. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of 1,4-Dihydropyridines via the Hantzsch Reaction Using a Recyclable HPW/PEG-400 Catalytic System. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010096

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Wender Alves, Sayuri Cristina Santos Takada, Claudia Cristina Gatto, and Izabella Vitoria Maravalho. 2026. "Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of 1,4-Dihydropyridines via the Hantzsch Reaction Using a Recyclable HPW/PEG-400 Catalytic System" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010096

APA StyleSilva, W. A., Takada, S. C. S., Gatto, C. C., & Maravalho, I. V. (2026). Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of 1,4-Dihydropyridines via the Hantzsch Reaction Using a Recyclable HPW/PEG-400 Catalytic System. Catalysts, 16(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010096