Metalloporphyrin-Based Covalent Organic Frameworks: Design, Construction, and Photocatalytic Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Strategies for the Design of MPor-COFs

2.1. Selection of the Metal Center

2.2. Design of the Linkage

3. Construction of MPor-COFs

3.1. Post-Synthesis Metallization

3.2. Pre-Metallization Followed by Synthesis

3.3. One-Pot Metallization Method

4. Photocatalytic Applications

4.1. Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production

4.2. Photocatalytic Carbon Dioxide Reduction

4.3. Photocatalytic Synthesis of Organics

4.4. Photocatalytic Degradation of Pollutants

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGlade, C.; Ekins, P. The geographical distribution of fossil fuels is unused when limiting global warming to 2 °C. Nature 2015, 517, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Ruan, Y.; Sun, J.; Yang, Q. India’s coal mining plan undermines climate goals. Science 2024, 383, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Tanaka, K.; Ciais, P.; Penuelas, J.; Balkanski, Y.; Sardans, J.; Hauglustaine, D.; Liu, W.; Xing, X.; et al. Accelerating the energy transition towards photovoltaic and wind in China. Nature 2023, 619, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, C.; Lu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Davidson, M.R. Spatially resolved land and grid model of carbon neutrality in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2306517121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzani, V.; Bergamini, G.; Ceroni, P. Photochemistry and photocatalysis. Rend. Lincei 2017, 28, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Domen, K. Particulate photocatalysts for light-driven water splitting: Mechanisms, challenges, and design strategies. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 919–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Cao, H.; Gao, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, R.; Chen, B.; Si, Q.; Xia, Y.; Wang, S. Electron donor-acceptor metal-organic frameworks for efficient photocatalytic reduction and oxidation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 692, 137561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Liu, F.; Tai, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Zhao, H.; Xia, Y.; Wang, S. Promoting photocatalytic performance of TiO2 nanomaterials by structural and electronic modulation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, L.; Crisenza, G.E.M.; Melchiorre, P. Mechanistic studies in photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3730–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ma, D. Recent advances in white organic light-emitting diodes. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2016, 107, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, V.W.-h.; Moudrakovski, I.; Botari, T.; Weinberger, S.; Mesch, M.B.; Duppel, V.; Senker, J.; Blum, V.; Lotsch, B.V. Rational design of carbon nitride photocatalysts by identification of cyanamide defects as catalytically relevant sites. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Cao, H.; Xu, L.; Fu, H.; Sun, S.; Xiao, Z.; Sun, C.; Long, X.; Xia, Y.; Wang, S. Design and preparation of highly active TiO(2) photocatalysts by modulating their band structure. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 629, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, Y.; Yang, B.; Li, J.; Meng, L.; Xing, P.; Wang, S. Design and preparation of heterostructured Cu2O/TiO2 materials for photocatalytic applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomić, J.; Malinović, N. Titanium dioxide photocatalyst: Present situation and future approaches. Aidasco Rev. 2023, 1, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokona, B.; Kim, A.M.; Roden, R.C.; Daniels, J.P.; Pepe-Mooney, B.J.; Kovaric, B.C.; de Paula, J.C.; Johnson, K.A.; Fairman, R. Self assembly of coiled-coil peptide−porphyrin complexes. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 1454–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, M.K.; Ladomenou, K.; Coutsolelos, A.G. Porphyrins in bio-inspired transformations: Light-harvesting to solar cell. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 2601–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, M.; Patil, A.J.; Sun, S.; Tian, L.; Zhang, D.; Cao, M.; Mann, S. Design and construction of artificial photoresponsive protocells capable of converting day light to chemical energy. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 24612–24616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Wei, R.; Wang, S.; Xia, Y.; Cao, M.; Wang, S. Peptide-mediated porphyrin based hierarchical complexes for light-to-chemical conversion. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 15201–15208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Yu, D.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Z.; Cao, M.; Xia, Y.; Liu, H. Short peptide-regulated aggregation of porphyrins for photoelectric conversion. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2019, 3, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Peng, J.; Liu, R.; Gao, J.; Hua, G.; Fan, X.; Wang, S. Porphyrin-based supramolecular self-assemblies: Construction, charge separation and transfer, stability, and application in photocatalysis. Molecules 2024, 29, 6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Du, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, B.; Wang, S. Porphyrin-based metal-organic framework materials: Design, construction, and application in the field of photocatalysis. Molecules 2024, 29, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gui, B.; Wang, W.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Sun, J.; Wang, C. Ultrahigh–surface area covalent organic frameworks for methane adsorption. Science 2024, 386, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, T.; Ji, S.; Shao, H.; Lin, M.; Seki, S.; Yan, N.; Jiang, D. Covalent organic framework photocatalysts for green and efficient photochemical transformations. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Shang, S.; Du, C.; Hong, J.; Gao, W.; Hua, C.; Xu, H.; You, Z.; et al. Topology-selective manipulation of two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 26900–26907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, L.; Dai, S.; Zhao, C.; Ma, C.; Wei, L.; Zhu, M.; Chong, S.Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, L.; et al. Reconstructed covalent organic frameworks. Nature 2022, 604, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tang, C.; Zhang, L.; Song, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. Porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks: Design, synthesis, photoelectric conversion mechanism, and applications. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auras, F.; Ascherl, L.; Bon, V.; Vornholt, S.M.; Krause, S.; Döblinger, M.; Bessinger, D.; Reuter, S.; Chapman, K.W.; Kaskel, S.; et al. Dynamic two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Lang, X. Imine-linked 2D covalent organic frameworks based on benzotrithiophene for visible-light-driven selective aerobic sulfoxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 7036–7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ge, F.; Yang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Shen, J. 1D covalent organic frameworks triggering highly efficient photosynthesis of H2O2 via controllable modular design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Diercks, C.S.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Kornienko, N.; Nichols, E.M.; Zhao, Y.; Paris, A.R.; Kim, D.; Yang, P.; Yaghi, O.M.; et al. Covalent organic frameworks comprising cobalt porphyrins for catalytic CO2 reduction in water. Science 2015, 349, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Gu, Y.-Y.; Ning, J.; Yan, Y.; Shi, L.; Zhou, M.; Wei, H.; Ren, X.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Boosting photocatalysis of hydrazone-linked covalent organic frameworks through introducing electron-rich conjugated aldehyde. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Chen, M.H.; Xu, Y.H.; Feng, Y.Q.; Song, J.; Zhang, B. Trans-A2B2-type metalloporphyrin-based donor-acceptor covalent organic frameworks for efficient photocatalytic CO2 cycloaddition to aziridines. Adv. Sci. 2025, e13754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Xu, J.; Liu, L.Z.H.; Sun, Q.Z.; Li, S.X.; Pan, Q.Y.; Zhao, Y.J. Metalloporphyrin-based highly conjugated three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks for the electrochemical hydrogen evolution reaction. Mater. Chem. Front. 2024, 8, 3186–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.L.; Su, Q.; Ding, W.L.; Liu, S.F.; Li, Z.X.; Cheng, W.G. Anions mediated electron-rich metalloporphyrin ionic framework as recyclable catalyst for conversion of urea into cyclic carbonates. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 399, 124468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzuan, N.H.M.; Ghazali, Z.; Hassan, N.I.; Bakar, M.B.; Hasbullah, S.A.; Abu Bakar, M. Synthesis and Characterization of 5,15 A2-Type porphyrin, metalloporphyrin and preliminary study on carbon dioxide adsorption. Sains Malays. 2025, 54, 1535–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; AlMasoud, N.; Alomar, T.S.; Nadeem, M.; Bhatti, M.H.; Munawar, K.S.; Tariq, M.; Asif, H.M.; Sohail, M. Synthesis of heterogeneous mesoporous tetrafunctionalalized porphyrin-aliphatic diamine based framework encapsulated vanadium containing POM as electrocatalyst for hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2024, 967, 118445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Jia, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wu, L.; Liu, J. π-Stacking-resistant cationic metalloporphyrin cof with dual-enzyme mimetics for infected wound therapy. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 14082–14095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Lis, T.; Bury, W.; Chmielewski, P.J.; Garbicz, M.; Stepien, M. Hierarchical self-assembly of curved aromatics: From donor-acceptor porphyrins to triply periodic minimal surfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202316243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Hou, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, M.J.; Wang, C.S.; Li, H.Y.; Kong, F.Y.; Wang, W. Photoelectrochemical detection of copper ions based on a covalent organic framework with tunable properties. Analyst 2024, 149, 2045–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.F.; Liu, T.C.; Wang, Z.Z.; Wang, Y.X.; Steven, M.; Luo, Y.H.; Luo, X.P.; Wang, Y. Regulating the spin-state of cobalt in three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks for high-performance sodium-iodine rechargeable batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202415759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, Y.D.; Feng, Q.; Tan, Y.X.; Xiao, Z.W.; Wang, Z.D.; Wu, H.Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.B. Engineering electron- and ion-transporting active pore channels in ultrathin covalent organic framework nanosheets for enhanced photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, L.; Zhang, L.; Du, X.; Cao, H.; Wang, D.; Hu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wang, S. Design and construction of noble-metal-free porphyrin-based light-harvesting antennas for efficient NADH generation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 2656–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Wang, Q.; Bian, Z.; Wang, G.; Xu, Y. supramolecular modulation of molecular conformation of metal porphyrins toward remarkably enhanced multipurpose electrocatalysis and ultrahigh-performance Zinc–Air batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2102062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.-J.; Si, D.-H.; Ye, S.; Dong, Y.-L.; Cao, R.; Huang, Y.-B. Photocoupled electroreduction of CO2 over photosensitizer-decorated covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 19856–19865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Han, X.; Bu, X.; Huang, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Song, W.-L. d-Orbital induced electronic structure reconfiguration toward manipulating electron transfer pathways of metallo-porphyrin for enhanced AlCl2+ storage. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2409904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.-Z.; Wu, J.-H.; Wang, B.-W.; Gao, S.; Zhang, J.-L. Coordination induced spin state transition switches the reactivity of Nickel (II) porphyrin in hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202413042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Huang, X.; Liu, M.; Gui, B.; Lang, X.; Wang, C. Promoting energy transfer pathway in porphyrin-based sp2 carbon-conjugated covalent organic frameworks for selective photocatalytic oxidation of sulfide. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2024, 43, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.G.; Yao, B.J.; Wu, W.X.; Yu, Z.G.; Wang, X.Y.; Kan, J.L.; Dong, Y.B. Metalloporphyrin and ionic liquid-functionalized covalent organic frameworks for catalytic co2 cycloaddition via visible-light-induced photothermal conversion. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 12591–12601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.J.; Liu, F.; Yan, L.S.; Suo, H.B.; Qian, J.Y.; Zou, B. Simultaneous determination of tert-butylhydroquinone, butylated hydroxyanisole and phenol in plant oil by metalloporphyrin-based covalent organic framework electrochemical sensor. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 122, 105486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisnabarreta, N.; Hao, Y.S.; Jin, E.Q.; Salamé, A.; Muellen, K.; Robert, M.; Lazzaroni, R.; Van Aert, S.; Mali, K.S.; De Feyter, S. Single-layered imine-linked porphyrin-based two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks targeting CO2 reduction. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2304371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borse, R.A.; Tan, Y.X.; Lin, J.; Zhou, E.B.; Hui, Y.D.; Yuan, D.Q.; Wang, Y.B. Coupling electron transfer and redox site in boranil covalent organic framework toward boosting photocatalytic water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202318136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Z.; Metin, Ö.; Meng, Z.; Jiang, H.L. Turning on singlet oxygen generation by outer-sphere microenvironment modulation in porphyrinic covalent organic frameworks for photocatalytic oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 63, e202314988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.W.; Ding, X.; Liu, Z.X.; Xu, Q.M.; Wang, H.L.; Xie, Y.S.; Jiang, J.Z. Two-dimensional copper-porphyrin covalent triazine framework for lithium-ion batteries. Nano Res. 2025, 18, 94908091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Zuo, K.M.; Li, Z.P.; Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Zeng, C.Y.; Xu, H.J.; Wang, B.S.; Gao, Y.A. Covalent organic frameworks for simultaneous CO2 capture and selective catalytic transformation. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, S.; Guan, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Waseem, A.; Metin, O.; Meng, Z.; Jiang, H.L. Regulating the generation of reactive oxygen species for photocatalytic oxidation by metalloporphyrinic covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.N.; He, L.L.; Huang, Q.; Liu, J.; Lan, Y.Q. Ferrocene-modified covalent organic framework for efficient oxygen evolution reaction and CO2 electroreduction. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 7922–7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.W.; Wu, H.Y.; Jiao, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.B. A dual-functional metalloporphyrin-fluorenone covalent organic framework for solar hydrogen and oxygen production. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 7515–7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Feng, X.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, H.; Liu, X.; Mu, Y. A 2D azine-linked covalent organic framework for gas storage applications. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 13825–13828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Mandal, S.K. In-depth experimental and computational investigations for remarkable gas/vapor sorption, selectivity, and affinity by a porous nitrogen-rich covalent organic framework. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chen, Y.-J.; Huang, X.; Dong, L.-Z.; Lu, M.; Guo, C.; Yuan, D.; Chen, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, S.-L.; et al. Porphyrin-Based COF 2D materials: Variable modification of sensing performances by post-metallization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202115308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, N.; Sun, X.; Chu, H.C.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.Y. Triple-signaling amplification strategy based electrochemical sensor design: Boosting synergistic catalysis in metal-metalloporphyrin-covalent organic frameworks for sensitive bisphenol A detection. Analyst 2021, 146, 4585–4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Tian, Y.; Wei, H.; Bai, Y.; Wu, F.; Yu, F.; Yu, P.; Mao, L. Tailoring the electrocatalytic properties of porphyrin covalent organic frameworks for highly selective oxygen sensing in vivo. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 3418–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.-W.; Li, W.; Gu, Y.; Su, J.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, S.; Zuo, J.-L.; Ma, J.; He, P. Covalent organic frameworks with Ni-Bis(dithiolene) and Co-porphyrin units as bifunctional catalysts for Li-O2 batteries. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadf2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhong, R.L.; Lu, M.; Wang, J.H.; Jiang, C.; Gao, G.K.; Dong, L.Z.; Chen, Y.F.; Li, S.L.; Lan, Y.Q. Single metal site and versatile transfer channel merged into covalent organic frameworks facilitate high-performance Li-CO2 batteries. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, S.; Peña-Duarte, A.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Noufal, M.; Saha, P.; Addicoat, M.A.; Sasaki, K.; Strom, T.A.; Yacamán, M.J.; et al. [2,1,3]-Benzothiadiazole-spaced co-porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks for O2 reduction. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 3492–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Duan, W.; Wang, J.; Sun, P.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, Z. A novel fully conjugated COF adorned on 3D-G to boost the “D–π–A” electron regulation in oxygen catalysis performance. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 9951–9965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soroushmanesh, M.; Dinari, M.; Farrokhpour, H. Comprehensive computational investigation of the porphyrin-based COF as a nanocarrier for delivering anti-cancer drugs: A combined MD simulation and DFT calculation. Langmuir 2024, 40, 19073–19085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, X.; Liao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Xi, K.; Huang, W.; Jia, X. Water-dispersible PEG-curcumin/amine-functionalized covalent organic framework nanocomposites as smart carriers for in vivo drug delivery. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, L.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Li, Y.; Tian, H.; Chen, X. Porphyrin-based covalent organic framework nanoparticles for photoacoustic imaging-guided photodynamic and photothermal combination cancer therapy. Biomaterials 2019, 223, 119459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, W.; Kang, D.W.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Germanas, T.; Nash, G.T.; Shen, Q.; Leech, R.; Li, J.; Engel, G.S.; et al. Simultaneous protonation and metalation of a porphyrin covalent organic framework enhance photodynamic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 16609–16618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.-K.; Jin, Y.-N.; Zhang, L.-J.; Wang, C.; Sun, J.-P.; Tung, C.-H.; Wu, L.-Z. Topology-optimized 3D metalloporphyrin covalent organic framework for photocatalytic CO2 fixation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 33060–33070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Liang, Z.; Qin, H.; Liu, X.; Zhai, B.; Su, Z.; Liu, Q.; Lei, H.; Liu, K.; Zhao, C.; et al. Large-area free-standing metalloporphyrin-based covalent organic framework films by liquid-air interfacial polymerization for oxygen electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202214449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Tan, Y.-X.; Lin, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, E.; Yuan, D.; Wang, Y. Coupling electrocatalytic redox-active sites in a three-dimensional bimetalloporphyrin-based covalent organic framework for enhancing carbon dioxide reduction and oxygen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 9478–9485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Kang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhou, T.; Wang, J.; Zhu, W.; et al. Enhanced photo-Fenton catalysis via bandgap engineering of metalloporphyrin-based covalent organic framework shells on bimetallic metal–organic frameworks: Accelerating Fe(iii)/Fe(ii) loop activation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 9952–9962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.C.; Sun, X.; Zha, X.Q.; Khan, S.U.; Wang, Y. Ultrasensitive electrochemical detection of butylated hydroxy anisole via metalloporphyrin covalent organic frameworks possessing variable catalytic active sites. Biosensors 2022, 12, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, L.; Chen, B.T.; Gao, Y.; Yu, B.Q.; Wang, Y.H.; Han, B.; Lin, C.X.; Bian, Y.Z.; Qi, D.D.; Jiang, J.Z. Covalent organic frameworks based on tetraphenyl-p-phenylenediamine and metalloporphyrin for electrochemical conversion of CO2 to CO. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 3217–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhang, S.B.; Yang, M.Y.; Liu, Y.F.; Liao, J.P.; Huang, P.; Zhang, M.; Li, S.L.; Su, Z.M.; Lan, Y.Q. Dual Photosensitizer coupled three-dimensional metal-covalent organic frameworks for efficient photocatalytic reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202307632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.M.; Zhou, C.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Xia, L.; Xue, D.; Li, J.; Wang, N. Construction of hydrophilic-and-cationic metalloporphyrin-based polymers for electrocatalytic small molecule activation. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 7385–7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Kong, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, S.; Li, P.-Z.; Zhao, Y. Integrating multifunctionalities into a 3D covalent organic framework for efficient CO2 photoreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202504772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. A full-spectrum metal-free porphyrin supramolecular photocatalyst for dual functions of highly efficient hydrogen and oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuki, J. Supramolecular approach towards light-harvesting materials based on porphyrins and chlorophylls. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 6710–6753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladomenou, K.; Natali, M.; Iengo, E.; Charalampidis, G.; Scandola, F.; Coutsolelos, A.G. Photochemical hydrogen generation with porphyrin-based systems. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 304–305, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenish Bashir, A.Z.C. Modulating the electronic structure of diphenyl metalloporphyrins. Chemrxiv 2025. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

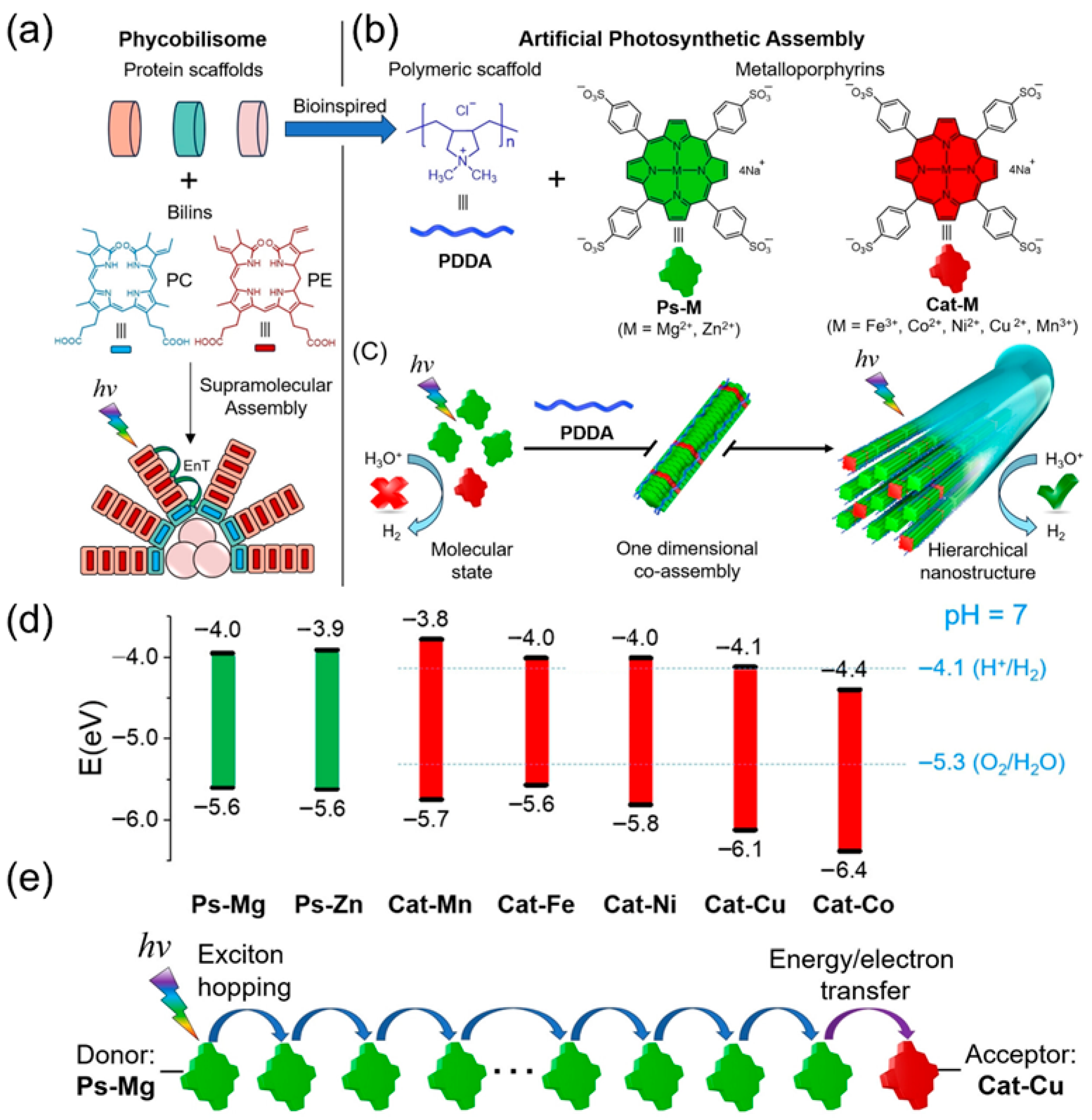

- Tang, Q.; Han, Y.; Chen, L.; Qi, Q.; Yu, J.; Yu, S.-B.; Yang, B.; Wang, H.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Xie, S.-H.; et al. Bioinspired self-assembly of metalloporphyrins and polyelectrolytes into hierarchical supramolecular nanostructures for enhanced photocatalytic H2 production in water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202315599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, B.; Liu, S.; Lü, X.; Cheng, X. Mechanism of optical limiting in metalloporphyrins under visible continuous radiation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 28213–28219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Ma, J.; Tan, Y.; Yu, G.; Qin, H.; Zheng, L.; Liu, H.; Li, R. Construction of porphyrin porous organic cage as a support for single cobalt atoms for photocatalytic oxidation in visible light. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 5827–5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-W.; Hu, K.-Q.; Li, X.-B.; Bin, Z.-N.; Wu, Q.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Guo, Z.-J.; Wu, W.-S.; Chai, Z.-F.; Mei, L.; et al. Thermally induced orderly alignment of porphyrin photoactive motifs in metal–organic frameworks for boosting photocatalytic CO2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 18148–18159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Feng, Y.; Wee, A.G.H.; Zhang, B. Porphyrin- and porphyrinoid-based covalent organic frameworks (COFs): From design, synthesis to applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 435, 213778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Feng, Y.; Wen, F.; Xu, X.; Wang, H.; Shui, Q.-J.; Huang, N. Topological control over porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks for elucidating electron transfer characteristics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202506977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhou, M.; Fan, F.; Wu, X.; Xu, H. Fully Conjugated 2D sp2 carbon-linked covalent organic frameworks for photocatalytic overall water splitting. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2305313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.-B.; Cheng, K.; Li, H.; Niu, K.; Luan, T.-X.; Kong, S.; Yu, W.W.; Li, P.-Z.; Zhao, Y. Integrating two photochromics into one three-dimensional covalent organic framework for synergistically enhancing multiple photocatalytic oxidations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202425668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Yang, X.; Hu, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shu, C.; Yang, X.; Gao, H.; Wang, X.; Hussain, I.; et al. Unprecedented photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production via covalent triazine frameworks constructed from fused building blocks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202416350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Yu, X.; Qin, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ren, S.; Li, L. Synergistic enhancement of photocatalytic hydrogen evolution in covalent organic frameworks via isoreticular design, isomerism, and protonation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202511200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yang, S.; Liu, M.; Yang, X.; Xu, Q.; Zeng, G.; Jiang, Z. Catalytic linkage engineering of covalent organic frameworks for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202304356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Gándara, F.; Asano, A.; Furukawa, H.; Saeki, A.; Dey, S.K.; Liao, L.; Ambrogio, M.W.; Botros, Y.Y.; Duan, X.; et al. Covalent organic frameworks with high charge carrier mobility. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 4094–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, K.; Li, T.-T. Porphyrin and phthalocyanine based covalent organic frameworks for electrocatalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 464, 214563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Sa, R.; Li, P.; Yuan, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, R. Metalloporphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks composed of the electron donor-acceptor dyads for visible-light-driven selective CO2 reduction. Sci. China Chem. 2020, 63, 1289–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Mal, A.; Gao, X.-Y.; Gao, L.; Qiao, L.; Li, X.-B.; Wu, L.-Z.; Wang, C. Rational design of isostructural 2D porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks for tunable photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Hao, H.; Huang, F.; Lang, X.; Wang, C. A 2D porphyrin-based covalent organic framework with TEMPO for cooperative photocatalysis in selective aerobic oxidation of sulfides. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 2255–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Chen, X.; Krishna, R.; Jiang, D. Two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks for carbon dioxide capture through channel-wall functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2986–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.F.; Ding, H.; Li, X.; Lang, X. Hydrazone-linked 2D porphyrinic covalent organic framework photocatalysis for visible light-driven aerobic oxidation of amines to imines. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 610, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, H.; Guo, C.; Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, H.-N.; Chen, Y.; Lan, Y.-Q. Hydrazone-linked covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202404941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, H.; Ortega-Guerrero, A.; Wang, L.; Xu, K.; Wang, M.; Park, S.; Hennersdorf, F.; Dianat, A.; et al. On-water surface synthesis of charged two-dimensional polymer single crystals via the irreversible Katritzky reaction. Nat. Synth. 2022, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Asada, M.; Xu, Q.; Dalapati, S.; Addicoat, M.A.; Brady, M.A.; Xu, H.; Nakamura, T.; Heine, T.; Chen, Q.; et al. Two-dimensional sp2 carbon–conjugated covalent organic frameworks. Science 2017, 357, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Shi, J.-L.; Ma, Y.; Lin, G.; Lang, X.; Wang, C. Designed Synthesis of a 2D porphyrin-based sp2 carbon-conjugated covalent organic framework for heterogeneous photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6430–6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, T.-X.; Wang, J.-R.; Li, K.; Li, H.; Nan, F.; Yu, W.W.; Li, P.-Z. Highly enhancing CO2 photoreduction by metallization of an imidazole-linked robust covalent organic framework. Small 2023, 19, 2303324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.-Y.; Yan, F.-Q.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Feng, P.-F.; Zou, R.-Y.; Wang, S.; Zang, S.-Q. A benzimidazole-linked bimetallic phthalocyanine–porphyrin covalent organic framework synergistically promotes CO2 electroreduction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 15732–15738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Yang, R.; Ma, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Peng, Q.; Huang, X. Imidazole-rich covalent organic frameworks for efficient and selective thorium ion capture. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 368, 132986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liao, J.-P.; Li, R.-H.; Sun, S.-N.; Lu, M.; Dong, L.-Z.; Huang, P.; Li, S.-L.; Cai, Y.-P.; Lan, Y.-Q. Green synthesis of bifunctional phthalocyanine-porphyrin COFs in water for efficient electrocatalytic CO2 reduction coupled with methanol oxidation. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qi, R.; Li, S.; Liu, W.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.; Ding, K.; Yu, Y. Triazine–porphyrin-based hyperconjugated covalent organic framework for high-performance photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 23396–23404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Jia, J.; Ma, S.; Zhi, Y.; Xia, H.; Liu, X. Fully π-conjugated, diyne-linked covalent organic frameworks formed via alkyne–alkyne cross-coupling reaction. Mater. Chem. Front. 2022, 6, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, A.; Shigemitsu, H.; Li, X.X.; Fujitsuka, M.; Osakada, Y.; Kida, T. Near-infrared light-driven H2O2 generation via metalloporphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks and nanodisks. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 9084–9088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.A.; Xu, Z.J.; Li, J.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Fang, Z.B.; Zhang, T. Anchoring single-atomic metal sites in metalloporphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202400556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.J.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.L.; Wang, N.; Li, J. A benzimidazole-linked porphyrin covalent organic polymers as efficient heterogeneous catalyst/photocatalyst. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2022, 36, e6820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Huang, H.L.; Zhu, H.J.; Zhong, C.L. Design and synthesis of novel pyridine-rich cationic covalent triazine framework for CO2 capture and conversion. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 329, 111526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, Z.; Feng, L.; Ting, F.; Lishi, Y.; Hongbo, S. A novel sensor based on metalloporphyrins-embedded covalent organic frameworks for rapid detection of antioxidants in plant oil. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 379, 133227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, D.H.; Liu, J.W.; Li, G.; Zhao, J.X. Two-dimensional metalloporphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks as bifunctional electrocatalysts for OER and ORR: A computational study. Mol. Catal. 2024, 568, 114517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.P.; Ren, Z.X.; Zhao, B.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Xie, J.; Wang, B.; Feng, X. Theory-guided design of n-confused porphyrinic covalent organic frameworks for oxygen reduction reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 8769–8777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.X.; Gong, K.; Zhao, B.; Chen, S.L.; Xie, J. Boosting the catalytic performance of metalloporphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks via coordination engineering for CO2 and O2 reduction. Mater. Chem. Front. 2024, 8, 1958–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Behera, S.; Munjal, R.; Chakraborty, A.; Mondal, B.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Non-noble-metal-based porphyrin covalent organic polymers as additive-/annealing-free electrocatalysts for water splitting and biomass oxidation. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 5183–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.T.; Yang, X.Y.; Wei, X.F.; Dai, F.N.; Zhang, T.; Wang, D.F.; Li, M.Y.; Jia, J.H.; She, Y.B.; Xu, G.D.; et al. Three-dimensional porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks with stp topology for an efficient electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.C.; Sun, Y.N.; Chen, G.J.; Dong, Y.B. A BINOL-phosphoric acid and metalloporphyrin derived chiral covalent organic framework for enantioselective α-benzylation of aldehydes. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 1906–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamel, D.; Khan, A.U. Covalent organic frameworks: A green approach to environmental challenges. Mater. Today Sustain. 2025, 30, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, K.; He, T.; Liu, R.; Dalapati, S.; Tan, K.T.; Li, Z.; Tao, S.; Gong, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Jiang, D. Covalent organic frameworks: Design, synthesis, and functions. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 8814–8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diercks, C.S.; Yaghi, O.M. The atom, the molecule, and the covalent organic framework. Science 2017, 355, eaal1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.J.; Overholts, A.C.; Hwang, N.; Dichtel, W.R. Insight into the crystallization of amorphous imine-linked polymer networks to 2D covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 3690–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Chen, L.; Dong, Y.; Jiang, D. Porphyrin-based two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks: Synchronized synthetic control of macroscopic structures and pore parameters. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 1979–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz de Greñu, B.; Torres, J.; García-González, J.; Muñoz-Pina, S.; de los Reyes, R.; Costero, A.M.; Amorós, P.; Ros-Lis, J.V. Microwave-assisted synthesis of covalent organic frameworks: A review. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, P.; Antonietti, M.; Thomas, A. Porous, covalent triazine-based frameworks prepared by ionothermal synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3450–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esrafili, A.; Wagner, A.; Inamdar, S.; Acharya, A.P. Covalent organic frameworks for biomedical applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2002090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Dai, Y.; Ye, B.; Wang, H. Two dimensional covalent organic framework materials for chemical fixation of carbon dioxide: Excellent repeatability and high selectivity. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 10780–10785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Liu, L.; Honsho, Y.; Saeki, A.; Seki, S.; Irle, S.; Dong, Y.; Nagai, A.; Jiang, D. High-rate charge-carrier transport in porphyrin covalent organic frameworks: Switching from hole to electron to ambipolar conduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2618–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Li, D.; Han, Y.; Jiang, H.-L. Photocatalytic molecular oxygen activation by regulating excitonic effects in covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 20763–20771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Su, Q.; Luo, K.; Liu, S.; Ren, H.; Wu, Q. Photoactive donor–acceptor covalent organic framework material for synergistic cyclization approach to imidazole derivatives. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2024, 38, e7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourda, L.; Krishnaraj, C.; Van Der Voort, P.; Van Hecke, K. Conquering the crystallinity conundrum: Efforts to increase quality of covalent organic frameworks. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 2811–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, F.; Lotsch, B.V. Solving the COF trilemma: Towards crystalline, stable and functional covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 8469–8500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, G.-B.; Yu, Z.-F.; Cao, J.; Tang, Y. Encapsulation and regeneration of perovskite film by in situ forming cobalt porphyrin polymer for efficient photovoltaics. CCS Chem. 2020, 2, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-J. SMTP-1: The first functionalized metalloporphyrin molecular sieves with large channels. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2730–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, K.; Raza, A.; Yao, L.; Van Gele, S.; Rodríguez-Camargo, A.; Vignolo-González, H.A.; Grunenberg, L.; Lotsch, B.V. Downsizing porphyrin covalent organic framework particles using protected precursors for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2313197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P.; Anderson, H. Cooperative self-assembly of double-strand conjugated porphyrin ladders. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 11538–11545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelifa, A.B.; Ezzayani, K.; Guergueb, M.; Loiseau, F.; Saint-Aman, E.; Nasri, H. Synthesis, molecular structure, spectroscopic characterization and antibacterial activity of the pyrazine magnesium porphyrin coordination polymer. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1227, 129508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourda, L.; Dansette, I.; Jena, H.S.; Chen, H.; Raza, A.; Vrielinck, H.; Van Hecke, K.; Van Der Voort, P.; Krishnaraj, C. Controlled synthesis of crystalline metalated porphyrin covalent organic frameworks through an assembler approach. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 9526–9534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Liu, R.; Liu, N.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Jiang, D. Vertically expanded covalent organic frameworks for photocatalytic water oxidation into oxygen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202416771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Deng, W.-Q.; Lu, X. Metallosalen covalent organic frameworks for heterogeneous catalysis. Interdiscip. Mater. 2024, 3, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, C.G.; Frey, L.; Guntermann, R.; Medina, D.D.; Cortés, E. Early stages of covalent organic framework formation imaged in operando. Nature 2024, 630, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gropp, C.; Ma, T.; Hanikel, N.; Yaghi, O.M. Design of higher valency in covalent organic frameworks. Science 2020, 370, eabd6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Lan, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Geng, K.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Jiang, D. 2D sp2 carbon-conjugated covalent organic frameworks for photocatalytic hydrogen production from water. Chem 2019, 5, 1632–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-H.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wu, J.-R.; Yang, B.; Yang, Y.-W. Construction of hydrazone-linked macrocycle-enriched covalent organic frameworks for highly efficient photocatalysis. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 5726–5739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.L.; Li, L.L.; Jiang, W.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wan, L.J.; Hu, J.S. MoS2/CdS Nanosheets-on-nanorod heterostructure for highly efficient photocatalytic H2 generation under visible light irradiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 15258–15266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, H.; Xiao, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.; Lv, T.; Thangamuthu, M.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Y.; et al. Single-atom Cu anchored catalysts for photocatalytic renewable H2 production with a quantum efficiency of 56. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Nomura, K.; Zhu, M.; Li, X.; Xue, J.; Majima, T.; Osakada, Y. Synthesis and photocatalytic activity of ultrathin two-dimensional porphyrin nanodisks via covalent organic framework exfoliation. Commun. Chem. 2019, 2, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Nomura, K.; Guedes, A.; Goto, T.; Sekino, T.; Fujitsuka, M.; Osakada, Y. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of porphyrin nanodisks prepared by exfoliation of metalloporphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 7172–7178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Huang, F.; Hu, Q.; He, D.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Yan, W.; Hu, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, S.; et al. Regulated photocatalytic CO2-to-CH3OH pathway by synergetic dual active sites of interlayer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 26478–26484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Ge, Z.; Xu, E.; Wang, L.; Yin, B.; Dou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Coupling photocatalytic reduction and biosynthesis towards sustainable CO2 upcycling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202423995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Pan, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, K.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, R.; Jiang, J. A scalable general synthetic approach toward ultrathin imine-linked two-dimensional covalent organic framework nanosheets for photocatalytic CO2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 17431–17440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Diao, Y.; Qin, X.; Xu, Z.; Ke, H.; Zhu, X. Donor–acceptor covalent organic frameworks of nickel(ii) porphyrin for selective and efficient CO2 reduction into CO. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 15587–15591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Jeon, J.-P.; Kim, Y.; Noh, H.-J.; Seo, J.-M.; Kim, J.; Lee, G.; Baek, J.-B. Cobalt-porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks with donor-acceptor units as photocatalysts for carbon dioxide reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202307991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.-N.; Zhong, W.; Li, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zheng, L.; Jiang, J.; Jiang, H.-L. Regulating Photocatalysis by spin-state manipulation of cobalt in covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 16723–16731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratley, C.; Fenner, S.; Murphy, J.A. Nitrogen-centered radicals in functionalization of sp2 systems: Generation, reactivity, and applications in synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 8181–8260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.K.; Guin, S.; Maiti, S.; Biswas, J.P.; Porey, S.; Maiti, D. Toolbox for distal C-H bond functionalizations in organic molecules. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 5682–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.; Nguyen, T.; Foisal, A.R.M.; Phan, H.P.; Nguyen, T.K.; Nguyen, N.T.; Dao, D.V. Optothermotronic effect as an ultrasensitive thermal sensing technology for solid-state electronics. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, S.-N.; Chen, X.-H.; Chen, M.-L.; Lin, J.-M.; Niu, Q.; Li, S.-L.; Liu, J.; Lan, Y.-Q. Predesign of covalent-organic frameworks for efficient photocatalytic dehydrogenative cross-coupling reaction. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2413638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, R.; Qin, Y.; Wang, H.; He, X. Changes in water quality along the process of coal chemical reverse osmosis wastewater advanced treatment: Spectral analysis and molecular level exploration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 360, 131267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Skillen, N.; Gunaratne, N.; Rooney, D.W.; Robertson, P.K.J. Removal of phthalates from aqueous solution by semiconductor photocatalysis: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, C.; Wang, C.; Song, P.; Zeng, Y.; Liang, M.; Cui, B.; Ji, M.; Xia, H.; Lu, F.; Xia, H. Tailoring the surface and interface structures of carbon nitride for enhanced photocatalytic self-Fenton process in pollutant degradation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 684, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Lei, Y.; Pang, M.; Qiu, J.; Fan, C.; Feng, Y.; Wang, D. Construction of highly active Fe/N-CQDs/MCN1 photocatalytic self-Fenton system for degradation of ciprofloxacin. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, M.; Li, H.; Shi, Q.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, B. Crystalline covalent organic frameworks based on mixed metallo- and tetrahydroporphyrin monomers for use as efficient photocatalysts in dye pollutant removal. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 4745–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Duan, Q.; Cui, X. Copper-porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks for efficient water remediation: A synergistic strategy of adsorption and photo-self-Fenton degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 511, 162241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Pollutant | Degradation Efficiency (%) | Time (min) | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | Charge Carrier Lifetime (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COF-HTBD [168] | RhB | Negligible | 180 | 17.72 | 0.53 |

| COF-HFeTBD [168] | RhB | 100 | 180 | 32 | 2.76 |

| COF-HCuTBD [169] | RhB | 55 | 180 | 44 | 1.05 |

| COF-HCoTBD [169] | RhB | 47 | 180 | 776.98 | - |

| CuTB-COF [169] | RhB | 66.4 | 60 | 800 | 4.13 |

| CuTP-COF [169] | RhB | 98.7 | 60 | 1726 | 4.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, R.; Jia, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wang, S. Metalloporphyrin-Based Covalent Organic Frameworks: Design, Construction, and Photocatalytic Applications. Catalysts 2026, 16, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010076

Liu R, Jia Y, Xia Y, Wang S. Metalloporphyrin-Based Covalent Organic Frameworks: Design, Construction, and Photocatalytic Applications. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Rui, Yuting Jia, Yongqing Xia, and Shengjie Wang. 2026. "Metalloporphyrin-Based Covalent Organic Frameworks: Design, Construction, and Photocatalytic Applications" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010076

APA StyleLiu, R., Jia, Y., Xia, Y., & Wang, S. (2026). Metalloporphyrin-Based Covalent Organic Frameworks: Design, Construction, and Photocatalytic Applications. Catalysts, 16(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010076