Optimization of the Acid Value Reduction in High Free Fatty Acid Crude Palm Oil via Esterification with Different Grades of Ethanol for Batch and Circulation Processes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Batch Esterification Process with Different Ethanol Types

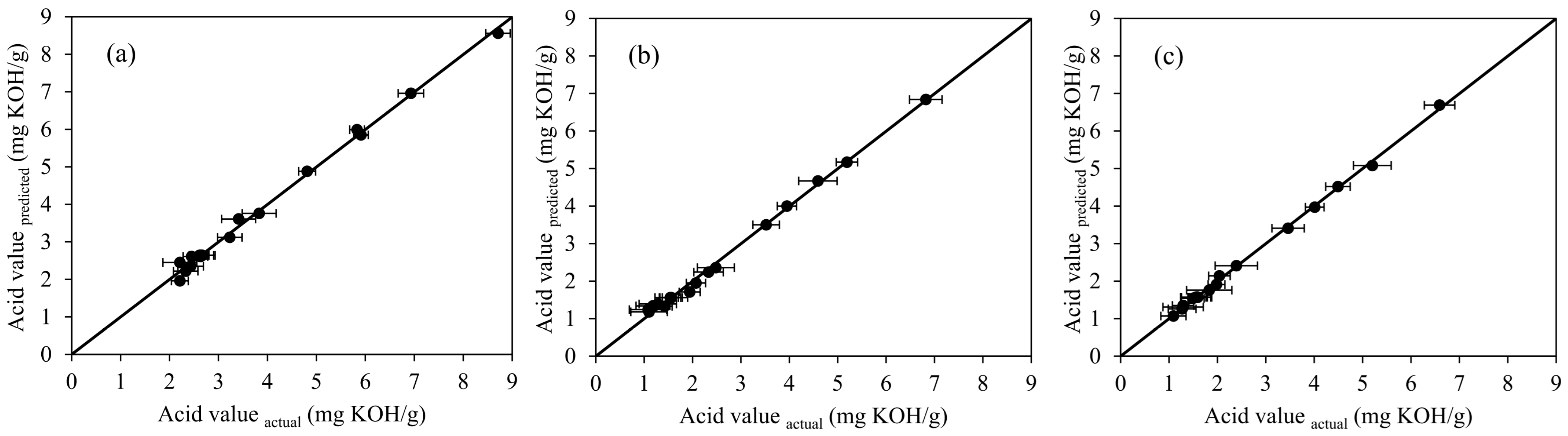

2.1.1. Experimental Results and Statistical Analysis for Batch Process

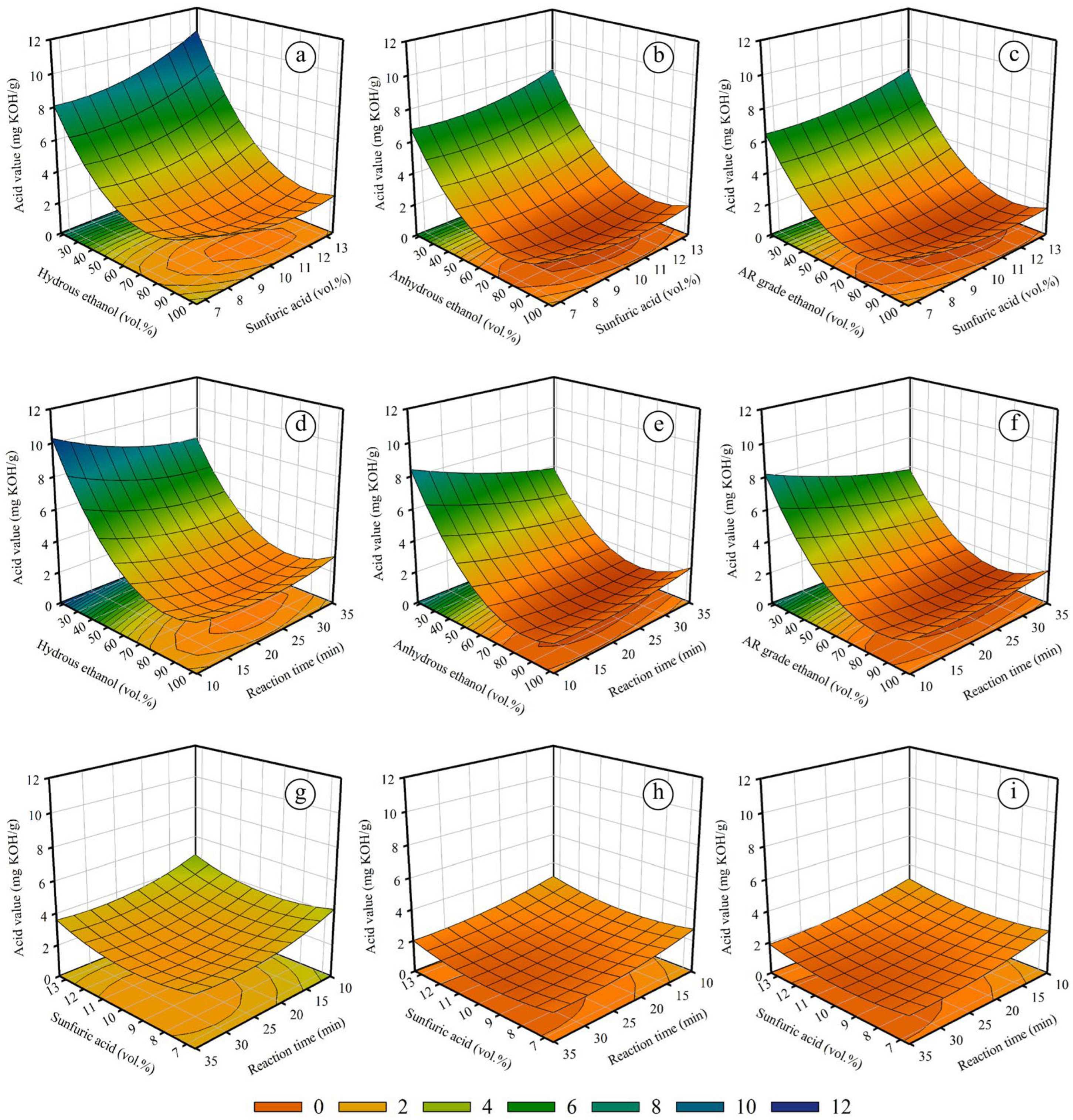

2.1.2. The Effect of Variables on Acid Value Reduction for Batch Process

2.1.3. Optimal Conditions and Production Costs for Batch Process

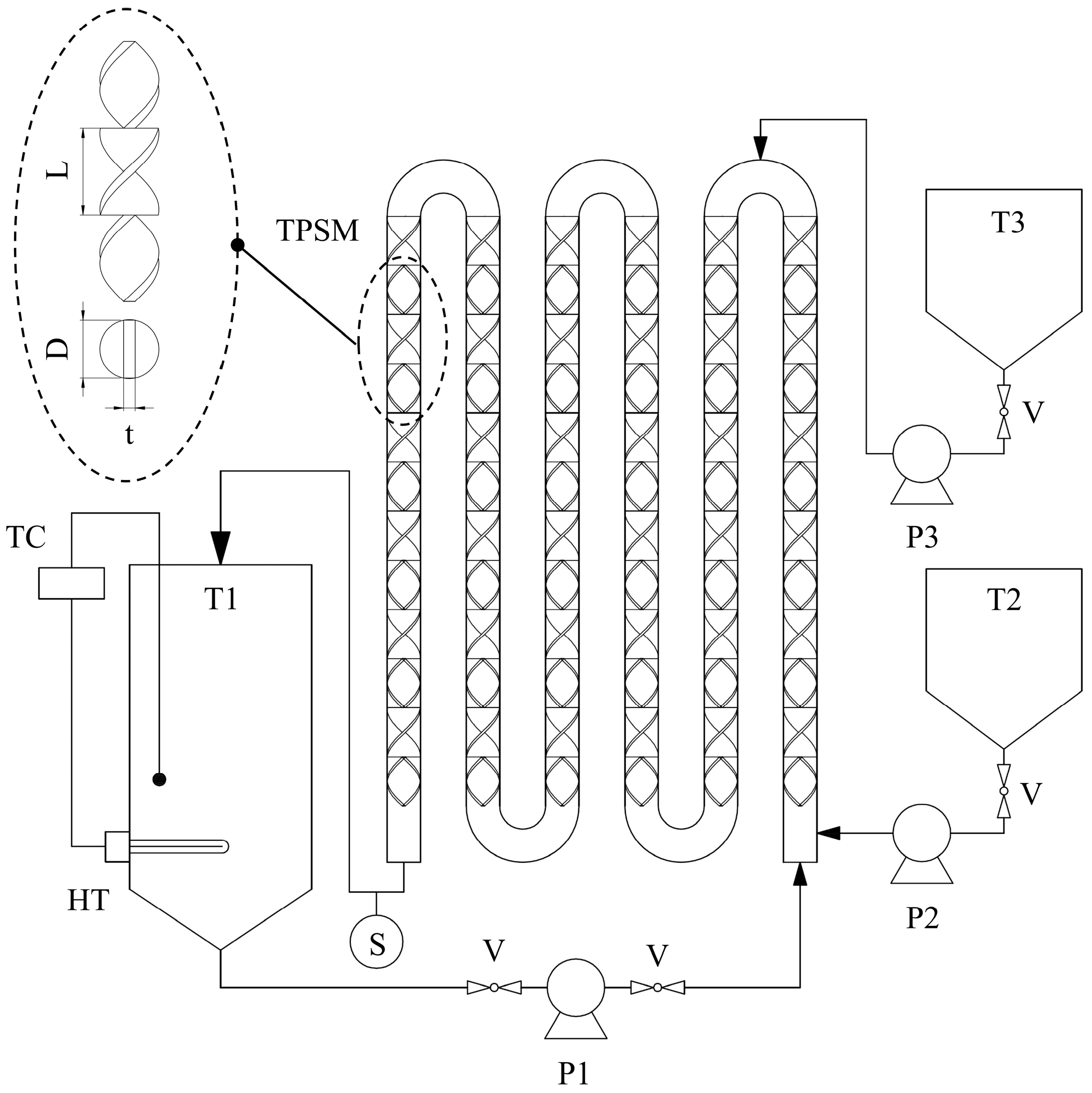

2.2. Circulation Esterification Process with Anhydrous Ethanol

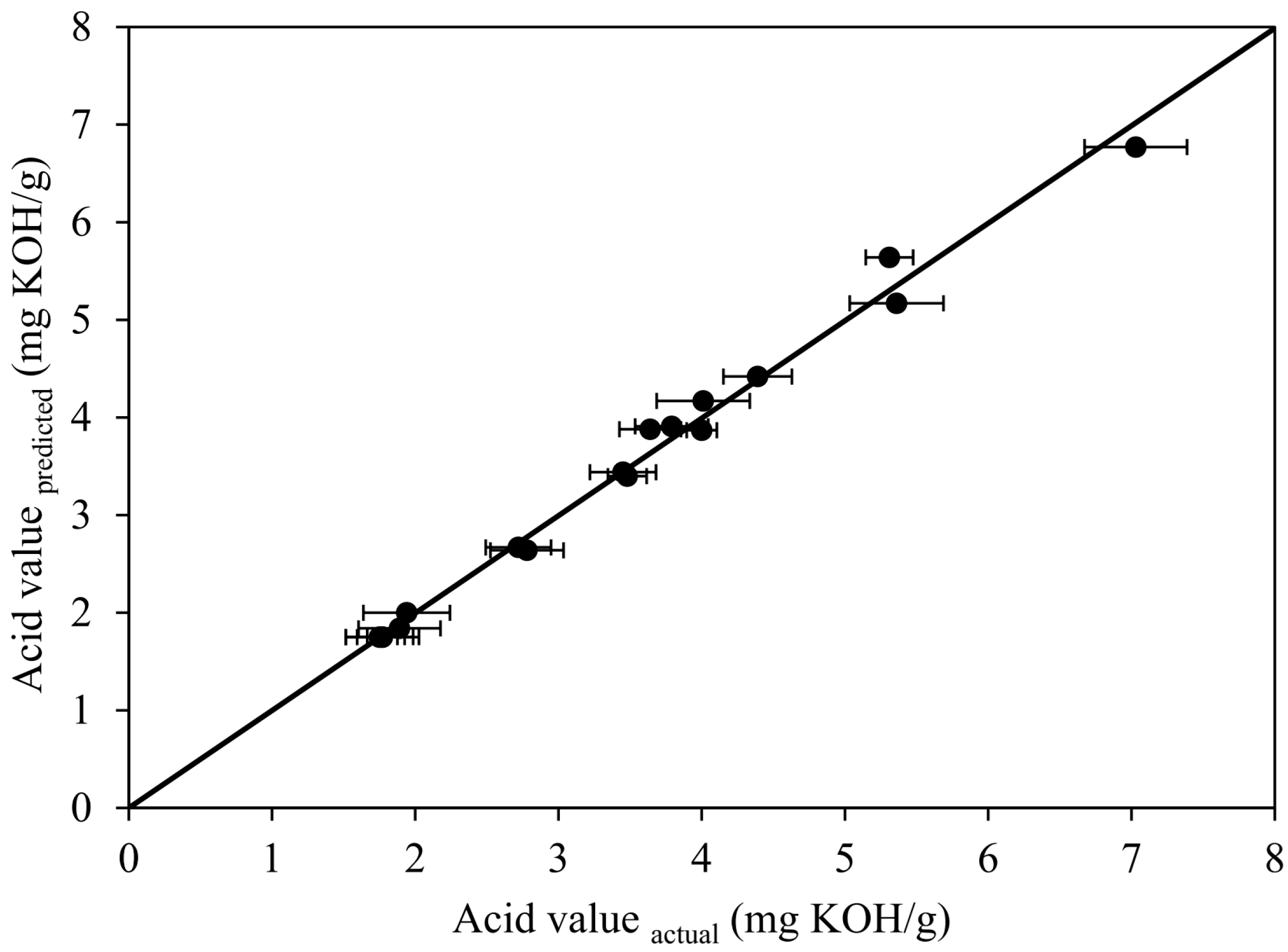

2.2.1. Experimental Results and Statistical Analysis for Circulation Process

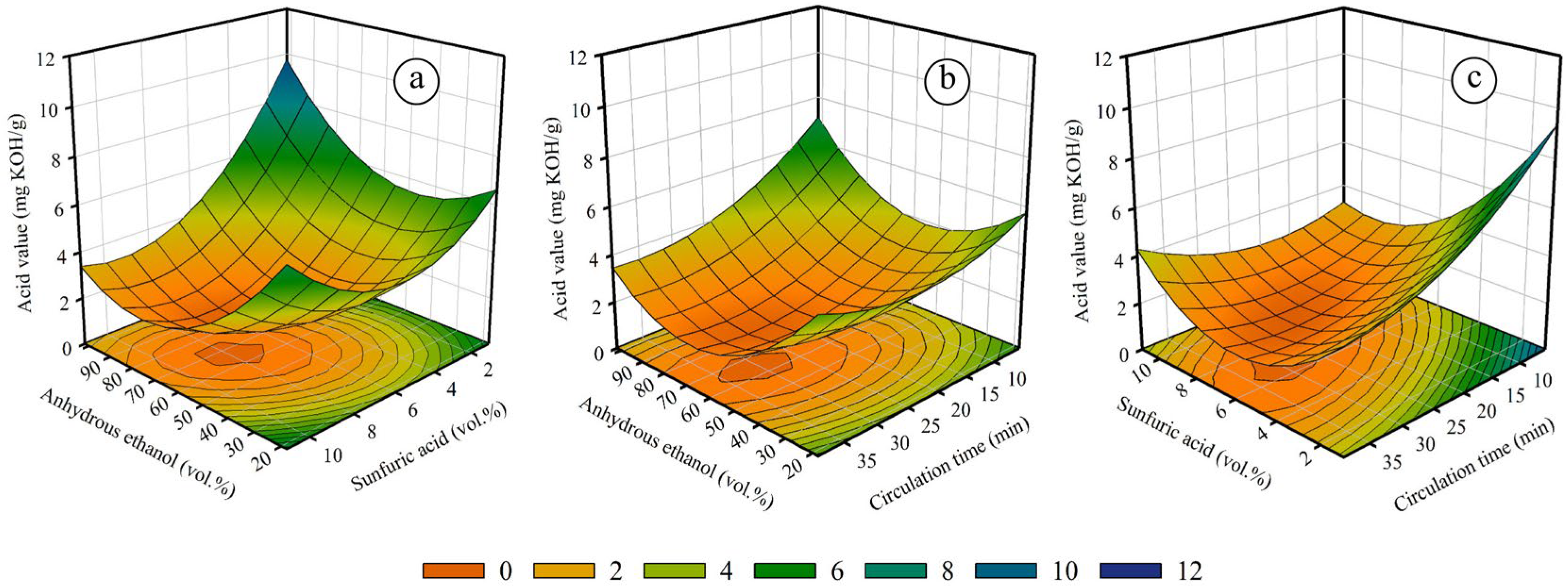

2.2.2. The Effect of Variables on Acid Value Reduction for Circulation Process

2.2.3. Optimal Conditions and Production Costs for Circulation Process

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Design of the Experiment for FFA Reduction in CPO

3.3. Experimental Procedure for the Batch Esterification Process

3.4. Experimental Procedure for the Circulation Esterification Process

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arshad, K.; Hussain, N.; Ashraf, M.H.; Saleem, M.Z. Air pollution and climate change as grand challenges to sustainability. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 928, 172370. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Azam, W. Natural resource scarcity, fossil fuel energy consumption, and total greenhouse gas emissions in top emitting countries. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Osman, W.N.A.; Rosli, M.H.; Mazli, W.N.A.; Samsuri, S. Comparative review of biodiesel production and purification. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banga, S.; Pathak, V.V. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil: A comprehensive review on the application of heterogenous catalysts. Energy Nexus. 2023, 10, 100209. [Google Scholar]

- Ebadian, M.; van Dyk, S.; McMillan, J.D.; Saddler, J. Biofuels policies that have encouraged their production and use: An international perspective. Energy Policy 2020, 147, 111906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, J.; Searle, S. Air Quality Impacts of Biodiesel in the United States; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunkunle, O.; Ahmed, N.A. Overview of biodiesel combustion in mitigating the adverse impacts of engine emissions on the sustainable human–environment scenario. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.N.K.; Wani, M.M. A comprehensive review on effects of nanoparticles–antioxidant additives–biodiesel blends on performance and emissions of diesel engine. Appl. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2020, 13, 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Naseef, H.H.; Tulaimat, R.H. Transesterification and esterification for biodiesel production: A comprehensive review of catalysts and palm oil feedstocks. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, A.; Dumas, S.; Mai, C.T.Q.; Ng, F.T.T. A kinetic model for a single step biodiesel production from a high free fatty acid (FFA) biodiesel feedstock over a solid heteropolyacid catalyst. Green Energy Environ. 2019, 4, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, S.; Hanif, M.A.; Rashid, U.; Hanif, A.; Akhtar, M.N.; Ngamcharussrivichai, C. Trends in widely used catalysts for fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) production: A review. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgharbawy, A.S.; Sadik, W.A.; Sadek, O.M.; Kasaby, M.A. A review on biodiesel feedstocks and production technologies. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2021, 66, 5098–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchero, M.; Gozzelino, G. A simple pseudo-homogeneous reversible kinetic model for the esterification of different fatty acids with methanol in the presence of amberlyst-15. Energies 2018, 11, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandari, V.; Devarai, S.K. Biodiesel production using homogeneous, heterogeneous, and enzyme catalysts via transesterification and esterification reactions: A critical review. BioEnergy Res. 2022, 15, 935–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litinas, A.; Geivanidis, S.; Faliakis, A.; Courouclis, Y.; Samaras, Z.; Keder, A.; Krasnoholovets, A.; Gandzha, I.; Zabulonov, Y.; Puhach, O.; et al. Biodiesel production from high FFA feedstocks with a novel chemical multifunctional process intensifier. Biofuel Res. J. 2020, 26, 1170–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasirajan, R. Biodiesel production by two step process from an energy source of Chrysophyllum albidum oil using homogeneous catalyst. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 37, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Javed, F.; Shamair, Z.; Hafeez, A.; Fazal, T.; Aslam, A.; Zimmerman, W.B.; Rehman, F. Current developments in esterification reaction: A review on process and parameters. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 103, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, R.; Taddeo, F.; Russo, V.; Turco, R.; Buonerba, A.; Grassi, A.; Di Serio, M.; Tesser, R. Production of sustainable biochemicals by means of esterification reaction and heterogeneous acid catalysts. ChemEngineering 2021, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, B.; Shukla, S.K.; Wang, R. Enabling catalysts for biodiesel production via transesterification. Catalysts 2023, 13, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, S.N.; Marchetti, J.M. Biodiesel production through sulfuric acid catalyzed transesterification of acidic oil Techno economic feasibility of different process alternatives. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 174, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estiasih, T.; Ahmadi, K. Bioactive compounds from palm fatty acid distillate and crude palm oil. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 65, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahma, S.; Nath, B.; Basumatary, B.; Das, B.; Saikia, P.; Patir, K.; Basumatary, S. Biodiesel production from mixed oils: A sustainable approach towards industrial biofuel production. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 10, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erchamo, Y.S.; Mamo, T.T.; Workneh, G.A.; Mekonnen, Y.S. Improved biodiesel production from waste cooking oil with mixed methanol–ethanol using enhanced eggshell-derived CaO nano-catalyst. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olukoya, I.A.; Bellmer, D.; Whiteley, J.R.; Aichele, C.P. Evaluation of the environmental impacts of ethanol production from sweet sorghum. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2015, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Araby, R. Biofuel production: Exploring renewable energy solutions for a greener future. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2024, 17, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larimi, A.; Harvey, A.P.; Phan, A.N.; Beshtar, M.; Wilson, K.; Lee, A.F. Aspects of reaction engineering for biodiesel production. Catalysts 2024, 14, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirappapa, N.; Thanachanan, N.; Assarat, R. Thailand’s Fuel Ethanol Industry Outlook. KResearch. Home Page. Available online: https://media.settrade.com/settrade/Documents/2025/Feb/20250218-K-Research-Ethanol-Industry.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency. Promotion and Status of Ethanol and Biodiesel Use. Home Page. Available online: https://www.dede.go.th/sections?section_id=103 (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Deus, M.S.; Deus, K.C.O.; Lira, D.S.; Oliveira, J.A.; Padilha, C.E.A.; Souza, D.F.S. Esterification of oleic acid for biodiesel production using a semibatch atomization apparatus. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 2023, 6957812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, N.; Theochari, G.; Emmanouilidou, E.; Angelova, D.; Toteva, V.; Lazaridou, A.; Mitkidou, S. Biodiesel production from high free fatty acid by-product of bioethanol production process. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1123, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, G.; Keshav, A.; Anandkumar, J. Experimental and kinetic study of esterification of acrylic acid with ethanol using homogeneous catalyst. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2016, 14, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, P.C.; Hamerski, F.; Corazza, M.L.; Luz, L.F.L., Jr.; Voll, F.A.P. Acid-catalyzed esterification of free fatty acids with ethanol: An assessment of acid oil pretreatment, kinetic modeling and simulation. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2018, 123, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chueluecha, N.; Kaewchada, A.; Jaree, A. Biodiesel synthesis using heterogeneous catalyst in a packed-microchannel. Energy Conv. Manag. 2017, 141, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hykkerud, A.; Marchetti, J.M. Esterification of oleic acid with ethanol in the presence of Amberlyst-15. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 95, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Guo, M.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Cui, P.; Zhou, S.; Yu, M. Synthesis of CaO/ZrO2 based catalyst by using UiO–66(Zr) and calcium acetate for biodiesel production. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnal, P.; Amruth, A.; Basawaraj, M.P.; Chethan, T.S.; Murthy, K.R.S.; Rajashekhara, S. Microwave-assisted esterification and transesterification of dairy scum oil for biodiesel production: Kinetics and optimisation studies. Indian Chem. Eng. 2021, 63, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, M.J.; Das, A.; Das, V.; Bhuyan, N.; Deka, D. Transesterification of waste cooking oil for biodiesel production catalyzed by Zn substituted waste egg shell derived CaO nanocatalyst. Fuel 2019, 242, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridwan, I.; Ghazali, M.; Kusmayadi, A.; Putra, R.D.; Marlina, N.; Andrijanto, E. The effect of co-solvent on esterification of oleic acid using Amberlyst 15 as solid acid catalyst in biodiesel production. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 156, 03002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Grains & BioProducts Council. Ethanol Market and Pricing Data—December 17, 2025. Home Page. Available online: https://grains.org/ethanol_report/ethanol-market-and-pricing-data-december-17-2025/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Global Scientific Co., Ltd. Ethanol Absolute AR 4L., RCI-Labscan. Home Page. Available online: https://www.glabbioresearch.com/product/83/ethanol-absolute-เอทานอล-4l-rci-labscan?utm.com (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Pavlović, S.; Šelo, G.; Marinković, D.; Planinić, M.; Tišma, M.; Stanković, M. Transesterification of sunflower oil over waste chicken eggshell-based catalyst in a microreactor: An optimization study. Micromachines 2021, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, M.; Ren, F.; Knothe, G.; Tu, Q. A greener alternative titration method for measuring acid values of fats, oils, and grease. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2019, 96, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.C.; Nguyen, M.-L.; Su, C.-H.; Ong, H.C.; Juan, H.-Y.; Wu, S.-J. Bio-derived catalysts: A current trend of catalysts used in biodiesel production. Catalysts 2021, 11, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, G.; Keshav, A.; Anandkumar, J. Review on pervaporation: Theory, membrane performance, and application to intensification of esterification reaction. J. Eng. 2015, 2015, 927068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Run | Ethanol (vol.%) | H2SO4 (vol.%) | Reaction Time (min) | Acid Value (mg KOH/g) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrous Ethanol | Anhydrous Ethanol | AR-Grade Ethanol | ||||||||||

| Actual | Predicted | Actual | Predicted | Actual | Predicted | |||||||

| 1 | 18 | (−1.682) | 10 | (0) | 22.5 | (0) | 8.71 | 8.56 | 6.82 | 6.84 | 6.59 | 6.69 |

| 2 | 35 | (−1) | 8 | (−1) | 15 | (−1) | 5.83 | 5.99 | 4.59 | 4.67 | 4.49 | 4.52 |

| 3 | 35 | (−1) | 8 | (−1) | 30 | (+1) | 4.81 | 4.88 | 3.52 | 3.50 | 3.46 | 3.41 |

| 4 | 35 | (−1) | 12 | (+1) | 15 | (−1) | 6.93 | 6.96 | 5.19 | 5.17 | 5.20 | 5.08 |

| 5 | 35 | (−1) | 12 | (+1) | 30 | (+1) | 5.91 | 5.85 | 3.95 | 4.00 | 4.01 | 3.97 |

| 6 | 60 | (0) | 6.6 | (−1.682) | 22.5 | (0) | 3.23 | 3.12 | 2.07 | 1.95 | 1.98 | 1.91 |

| 7 | 60 | (0) | 10 | (0) | 9.9 | (−1.682) | 3.83 | 3.76 | 2.48 | 2.36 | 2.39 | 2.41 |

| 8 | 60 | (0) | 10 | (0) | 22.5 | (0) | 2.63 | 2.64 | 1.54 | 1.56 | 1.59 | 1.57 |

| 9 | 60 | (0) | 10 | (0) | 22.5 | (0) | 2.61 | 2.64 | 1.54 | 1.56 | 1.55 | 1.57 |

| 10 | 60 | (0) | 10 | (0) | 22.5 | (0) | 2.67 | 2.64 | 1.56 | 1.56 | 1.59 | 1.57 |

| 11 | 60 | (0) | 10 | (0) | 22.5 | (0) | 2.65 | 2.64 | 1.55 | 1.56 | 1.57 | 1.57 |

| 12 | 60 | (0) | 10 | (0) | 35.1 | (+1.682) | 2.45 | 2.61 | 1.42 | 1.33 | 1.29 | 1.31 |

| 13 | 60 | (0) | 13.4 | (+1.682) | 22.5 | (0) | 3.41 | 3.61 | 2.33 | 2.24 | 2.04 | 2.14 |

| 14 | 85 | (+1) | 8 | (−1) | 15 | (−1) | 2.63 | 2.61 | 1.28 | 1.39 | 1.49 | 1.54 |

| 15 | 85 | (+1) | 8 | (−1) | 30 | (+1) | 2.43 | 2.35 | 1.18 | 1.34 | 1.29 | 1.35 |

| 16 | 85 | (+1) | 12 | (+1) | 15 | (−1) | 2.33 | 2.22 | 1.08 | 1.24 | 1.27 | 1.26 |

| 17 | 85 | (+1) | 12 | (+1) | 30 | (+1) | 2.21 | 1.96 | 1.10 | 1.18 | 1.09 | 1.07 |

| 18 | 102 | (+1.682) | 10 | (0) | 22.5 | (0) | 2.21 | 2.45 | 1.94 | 1.71 | 1.83 | 1.76 |

| Coefficient | Hydrous Ethanol, Equation (1) | Anhydrous Ethanol, Equation (2) | AR-Grade Ethanol, Equation (3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | p-Value | Value | p-Value | Value | p-Value | |

| β0 | 18.8014 | 1.5679 × 10−6 | 16.9510 | 5.2389 × 10−7 | 15.1988 | 1.2853 × 10−8 |

| β1 | −0.2256 | 4.1835 × 10−7 | −0.2466 | 2.5685 × 10−8 | −0.2248 | 5.0859 × 10−10 |

| β2 | −0.8064 | 1.2733 × 10−2 | −0.7101 | 7.3474 × 10−3 | −0.5164 | 2.0561 × 10−3 |

| β3 | −0.2695 | 2.0112 × 10−4 | −0.2112 | 2.1810 × 10−4 | −0.1974 | 5.5612 × 10−6 |

| β4 | −0.0068 | 4.0607 × 10−4 | −0.0033 | 9.0598 × 10−3 | −0.0042 | 4.7931 × 10−5 |

| β5 | 0.0011 | 7.3226 × 10−3 | 0.0015 | 3.1867 × 10−4 | 0.0012 | 2.3379 × 10−5 |

| β6 | 0.0016 | 7.4724 × 10−9 | 0.0015 | 1.5385 × 10−9 | 0.0015 | 1.5960 × 10−11 |

| β7 | 0.0644 | 5.7247 × 10−4 | 0.0475 | 9.2970 × 10−4 | 0.0401 | 6.4891 × 10−5 |

| β8 | 0.0034 | 3.5846 × 10−3 | 0.0018 | 2.9433 × 10−2 | 0.0018 | 1.8079 × 10−3 |

| R2 | 0.995 | 0.996 | 0.999 | |||

| R2adjiusted | 0.991 | 0.993 | 0.997 | |||

| Source | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F0 | Fcritical | Degrees of Freedom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrous ethanol, Equation (1) | |||||

| Regression | 61.3185 | 7.6648 | 246.11 | 3.23 | 8 |

| Residual | 0.2803 | 0.0311 | 9 | ||

| Total | 61.5988 | 17 | |||

| Anhydrous ethanol, Equation (2) | |||||

| Regression | 45.7631 | 5.7204 | 292.46 | 3.23 | 8 |

| Residual | 0.1760 | 0.0196 | 9 | ||

| Total | 45.9391 | 17 | |||

| AR-grade ethanol, Equation (3) | |||||

| Regression | 42.9311 | 5.3664 | 800.51 | 3.23 | 8 |

| Residual | 0.0603 | 0.0067 | 9 | ||

| Total | 42.9914 | 17 | |||

| Parameter | Unit | Hydrous Ethanol | Anhydrous Ethanol | AR-Grade Ethanol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethyl ester | wt.% | 11.14 | 15.26 | 15.96 |

| Free fatty acid | wt.% | 0.47 | 0.27 | 0.26 |

| Triglyceride | wt.% | 78.67 | 74.58 | 73.85 |

| Diglyceride | wt.% | 8.98 | 9.30 | 9.23 |

| Monoglyceride | wt.% | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.70 |

| Parameter | Unit | Condition | Volume (L/Batch) | Chemical Price (USD/L) 1 | Production Cost (USD/Batch) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrous ethanol | vol.% | 82.7 | 0.83 | 0.495 | 0.411 |

| H2SO4 | vol.% | 10.6 | 0.11 | 1.153 | 0.127 |

| Reaction time | min | 25.4 | 0.022 | ||

| Total cost | 0.560 | ||||

| Anhydrous ethanol | vol.% | 78.1 | 0.78 | 0.527 | 0.411 |

| H2SO4 | vol.% | 10.2 | 0.10 | 1.153 | 0.115 |

| Reaction time | min | 26.3 | 0.023 | ||

| Total cost | 0.549 | ||||

| AR-grade ethanol | vol.% | 77.7 | 0.78 | 11.480 | 8.954 |

| H2SO4 | vol.% | 10.5 | 0.11 | 1.153 | 0.127 |

| Reaction time | min | 28.6 | 0.025 | ||

| Total cost | 9.106 |

| Run | Anhydrous Ethanol (vol.%) | H2SO4 (vol.%) | Circulation Time (min) | Acid Value (mg KOH/g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual | Predicted | |||||||

| 1 | 18 | (−1.682) | 6 | (0) | 22 | (0) | 4.39 | 4.42 |

| 2 | 35 | (−1) | 3 | (−1) | 12 | (−1) | 5.36 | 5.17 |

| 3 | 35 | (−1) | 3 | (−1) | 32 | (+1) | 3.48 | 3.40 |

| 4 | 35 | (−1) | 9 | (+1) | 12 | (−1) | 3.45 | 3.44 |

| 5 | 35 | (−1) | 9 | (+1) | 32 | (+1) | 3.79 | 3.91 |

| 6 | 60 | (0) | 1 | (−1.682) | 22 | (0) | 5.31 | 5.64 |

| 7 | 60 | (0) | 6 | (0) | 5.2 | (−1.682) | 3.64 | 3.88 |

| 8 | 60 | (0) | 6 | (0) | 22 | (0) | 1.75 | 1.75 |

| 9 | 60 | (0) | 6 | (0) | 22 | (0) | 1.77 | 1.75 |

| 10 | 60 | (0) | 6 | (0) | 22 | (0) | 1.76 | 1.75 |

| 11 | 60 | (0) | 6 | (0) | 22 | (0) | 1.77 | 1.75 |

| 12 | 60 | (0) | 6 | (0) | 38.8 | (+1.682) | 1.89 | 1.84 |

| 13 | 60 | (0) | 11 | (+1.682) | 22 | (0) | 2.78 | 2.64 |

| 14 | 85 | (+1) | 3 | (−1) | 12 | (−1) | 7.03 | 6.77 |

| 15 | 85 | (+1) | 3 | (−1) | 32 | (+1) | 4.00 | 3.87 |

| 16 | 85 | (+1) | 9 | (+1) | 12 | (−1) | 2.72 | 2.67 |

| 17 | 85 | (+1) | 9 | (+1) | 32 | (+1) | 1.94 | 2.00 |

| 18 | 102 | (+1.682) | 6 | (0) | 22 | (0) | 4.01 | 4.17 |

| Coefficient | Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| β0 | 13.6864 | 2.0517 × 10−7 |

| β1 | −0.1032 | 1.1113 × 10−4 |

| β2 | −1.3783 | 2.3496 × 10−6 |

| β3 | −0.2768 | 5.4510 × 10−5 |

| β4 | −0.0079 | 4.5896 × 10−5 |

| β5 | −0.0011 | 5.3813 × 10−3 |

| β6 | 0.0186 | 7.2979 × 10−5 |

| β7 | 0.0014 | 3.7135 × 10−7 |

| β8 | 0.0955 | 5.8862 × 10−7 |

| β9 | 0.0039 | 1.7672 × 10−4 |

| R2 | 0.991 | |

| R2adjiusted | 0.980 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F0 | Fcritical | Degrees of Freedom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 38.2141 | 4.2460 | 94.23 | 3.39 | 9 |

| Residual | 0.3605 | 0.0451 | 8 | ||

| Total | 38.5746 | 17 |

| Parameter | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Ethyl ester | wt.% | 15.00 |

| Free fatty acid | wt.% | 0.38 |

| Triglyceride | wt.% | 77.46 |

| Diglyceride | wt.% | 6.11 |

| Monoglyceride | wt.% | 1.05 |

| Parameter | Unit | Condition | Volume (L/Batch) | Chemical Price (USD/L) 1 | Production Cost (USD/Batch) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anhydrous ethanol | vol.% | 66.9 | 0.67 | 0.527 | 0.353 |

| H2SO4 | vol.% | 7.3 | 0.07 | 1.153 | 0.081 |

| Circulation time | min | 27.7 | 0.026 | ||

| Total cost | 0.460 |

| Property | Hydrous Ethanol | Anhydrous Ethanol | AR-Grade Ethanol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol content (vol.%) | 95.0 | 99.9 | 99.9 |

| Density (kg/L) at 20 °C | 0.800 | 0.7892 | 0.790 |

| Water content (by Coulometry, wt.%) | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Alkalinity | Not available | Not detected | 0.0002 |

| Color (Pt-Co) | 15 | 10 | 10 |

| Methanol (%) | 0.01 | Not detected | 0.05 |

| Residue on evaporation (wt.%) | Not available | 0.002 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Thawornprasert, J.; Pongraktham, K.; Theppaya, T.; Somnuk, K. Optimization of the Acid Value Reduction in High Free Fatty Acid Crude Palm Oil via Esterification with Different Grades of Ethanol for Batch and Circulation Processes. Catalysts 2026, 16, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010050

Thawornprasert J, Pongraktham K, Theppaya T, Somnuk K. Optimization of the Acid Value Reduction in High Free Fatty Acid Crude Palm Oil via Esterification with Different Grades of Ethanol for Batch and Circulation Processes. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleThawornprasert, Jarernporn, Kritsakon Pongraktham, Thanansak Theppaya, and Krit Somnuk. 2026. "Optimization of the Acid Value Reduction in High Free Fatty Acid Crude Palm Oil via Esterification with Different Grades of Ethanol for Batch and Circulation Processes" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010050

APA StyleThawornprasert, J., Pongraktham, K., Theppaya, T., & Somnuk, K. (2026). Optimization of the Acid Value Reduction in High Free Fatty Acid Crude Palm Oil via Esterification with Different Grades of Ethanol for Batch and Circulation Processes. Catalysts, 16(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010050