Selective Production of Hydrogen and Lactate from Glycerol Dehydrogenation Catalyzed by a Ruthenium PN3P Pincer Complex

Abstract

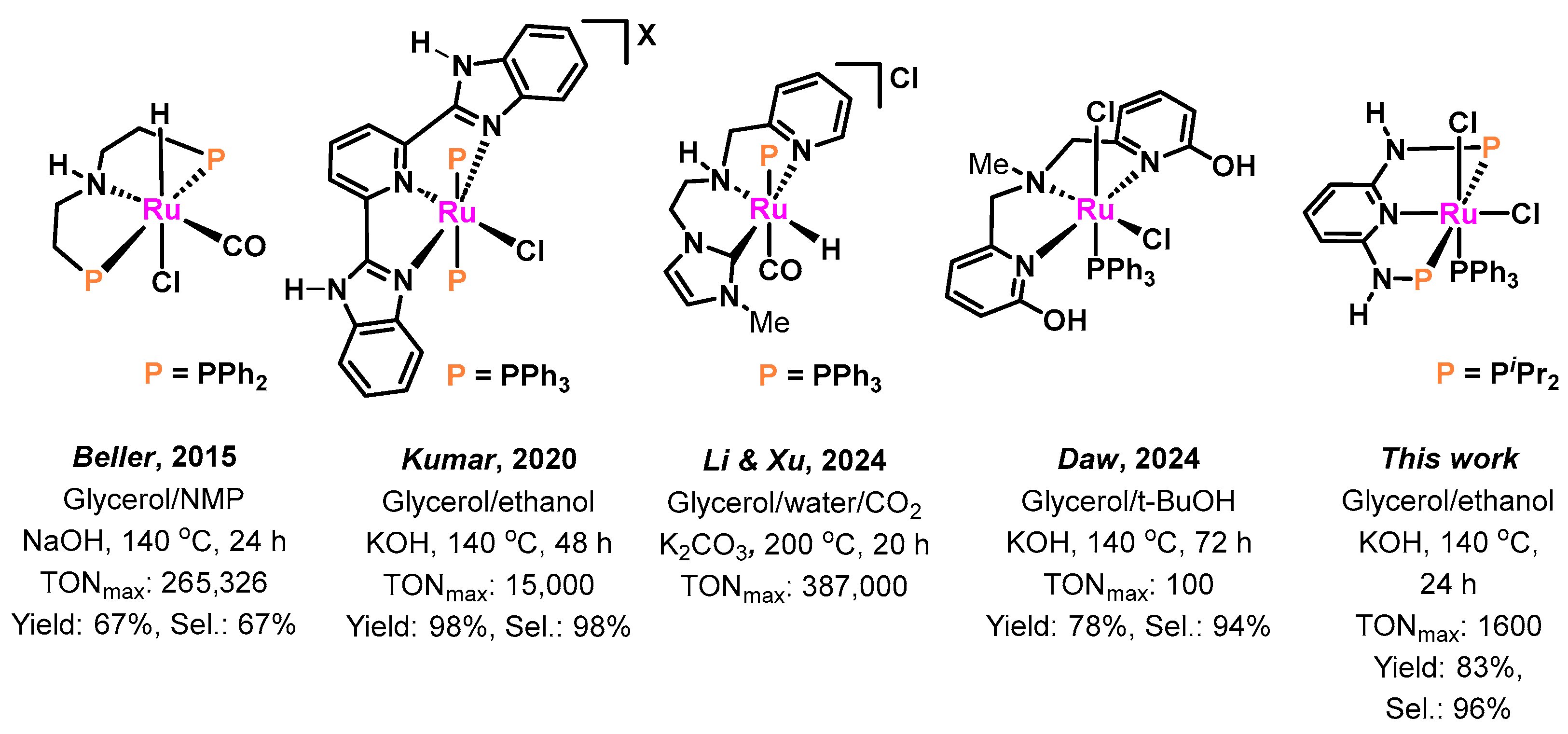

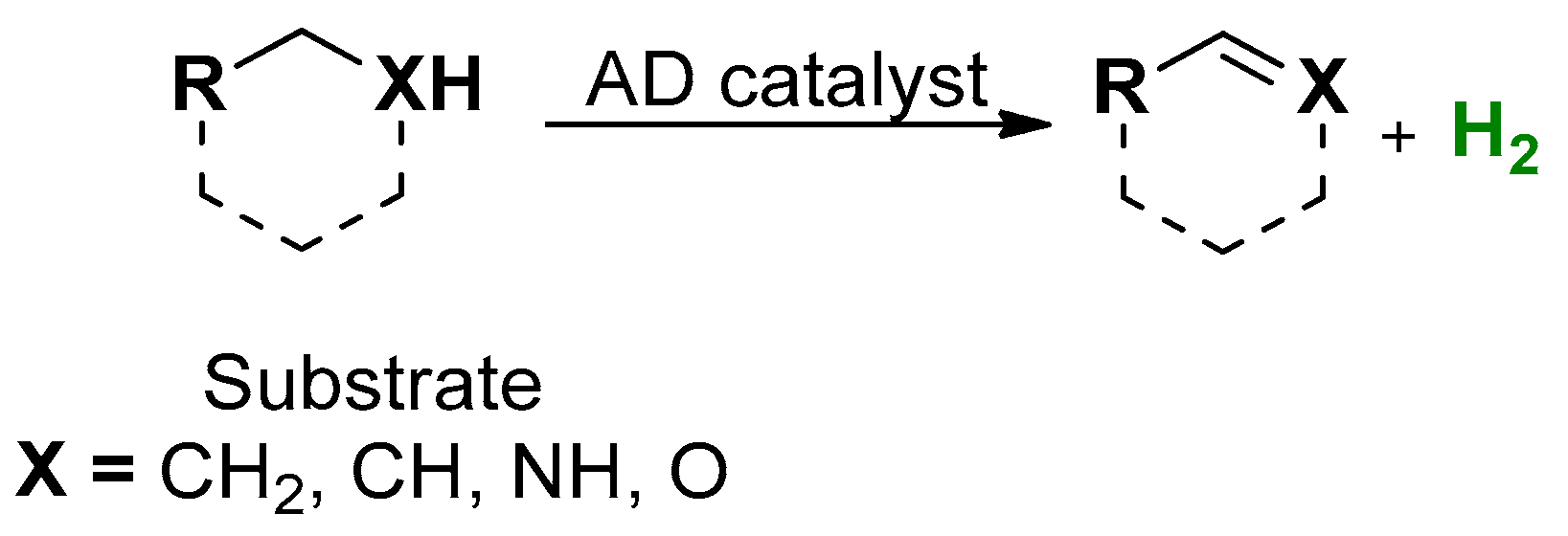

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Catalytic Tests

2.2. Mechanistic Studies

3. Experimental Section

General Procedure for Glycerol Catalytic Dehydrogenation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christopher, K.; Dimitrios, R. A review on exergy comparison of hydrogen production methods from renewable energy sources. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6640–6651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaroli, N.; Balzani, V. The hydrogen issue. ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shen, S.; Guo, L.; Mao, S.S. Semiconductor-based photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6503–6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maschmeyer, T.; Che, M. Catalytic Aspects of Light-Induced Hydrogen Generation in Water with TiO2 and Other Photocatalysts: A Simple and Practical Way Towards a Normalization? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1536–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artero, V.; Chavarot-Kerlidou, M.; Fontecave, M. Splitting water with cobalt. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 7238–7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortright, R.D.; Davda, R.R.; Dumesic, J.A. Hydrogen from catalytic reforming of biomass-derived hydrocarbons in liquid water. Nature 2002, 418, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azadi, P.; Farnood, R. Review of heterogeneous catalysts for sub-and supercritical water gasification of biomass and wastes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 9529–9541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.F.; Anshika Sortais, J.B.; Elangovan, S. Transition-Metal-Catalysed Transfer Hydrogenation Reactions with Glycerol and Carbohydrates as Hydrogen Donors. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, 202301278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendisch, V.F.; Lindner, S.N.; Meiswinkel, T.M. Use of Glycerol in Biotechnological Applications. In Biodiesel-Quality, Emissions and By-Products; Montero, G., Stoytcheva, M., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011; pp. 305–340. [Google Scholar]

- Rubianto, L.; Sudarminto, H.P.; Udjiana, S. Combination of biodiesel, glycerol, and methanol as liquid fuel. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1073, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attarbachi, T.; Kingsley, M.D.; Spallina, V. New trends on crude glycerol purification: A review. Fuel 2023, 340, 127485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, P.D.; Rodrigues, A.E. Glycerol reforming for hydrogen production: A review. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2009, 32, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.H.; Bloomfield, A.J.; Anastas, P.T. A switchable route to valuable commodity chemicals from glycerol via electrocatalytic oxidation with an earth abundant metal oxidation catalyst. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1958–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainembabazi, D.; Wang, K.; Finn, M.; Ridenour, J.; Voutchkova-Kostal, A. Efficient transfer hydrogenation of carbonate salts from glycerol using water-soluble iridium N-heterocyclic carbene catalysts. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 6093–6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, T.; Zhang, P.; Song, J.; Xie, C.; Han, B. Efficient Generation of Lactic Acid from Glycerol over a Ru-Zn-CuI/Hydroxyapatite Catalyst. Chem. Asian J. 2017, 12, 1598–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Daw, P.; Milstein, D. Homogeneous Catalysis for Sustainable Energy: Hydrogen and Methanol Economies, Fuels from Biomass, and Related Topics. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 385–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Sivakumar, G.; Gupta, V.; Balaraman, E. Recent Advances in Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers: An Alcohol-Based Hydrogen Economy. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 14712–14726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisarya, A.; Karim, S.; Narjinari, H.; Banerjee, A.; Arora, V.; Dhole, S.; Dutta, A.; Kumar, A. Production of hydrogen from alcohols via homogeneous catalytic transformations mediated by molecular transition-metal complexes. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 4148–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusselier, M.; Van Wouwe, P.; Dewaele, A.; Makshina, E.; Sels, B.F. Lactic acid as a platform chemical in the biobased economy: The role of chemocatalysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1415–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komesu, A.; de Oliveira, J.A.R.; da Silva Martins, L.H.; Maciel, M.R.W.; Filho, R.M. Lactic Acid Production to Purification: A Review. BioResources 2017, 12, 4364–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, M.A.; Sonomoto, K. Opportunities to overcome the current limitations and challenges for efficient microbial production of optically pure lactic acid. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 236, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, S.J.; Brar, S.K.; Sydney, E.B.; Le Bihan, Y.; Buelna, G.; Soccol, C.R. Microbial hydrogen production by bioconversion of crude glycerol: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 6473–6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, A.C.C.; Silveira, J.L. Hydrogen production utilizing glycerol from renewable feedstocks—The case of Brazil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1835–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.W.; Shabaker, J.W.; Dumesic, J.A. Raney Ni-Sn Catalyst for H2 Production from Biomass-Derived Hydrocarbons. Science 2003, 300, 2075–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.H.; Moon, D.J. Aqueous phase reforming of glycerol over Ni-based catalysts for hydrogen production. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011, 11, 7311–7314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Yi, X.; Delidovich, I.; Palkovits, R.; Shi, J.; Wang, X. Hetropolyacid-Catalyzed Oxidation of Glycerol into Lactic Acid under Mild Base-Free Conditions. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 4195–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Liu, P.; Cao, H.; Bals, S.; Heeres, H.J.; Pescarmona, P.P. Pt/ZrO2 Prepared by Atomic Trapping: An Efficient Catalyst for the Conversion of Glycerol to Lactic Acid with Concomitant Transfer Hydrogenation of Cyclohexene. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 9953–9963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, H.; Ren, Y.; Liu, H. Efficient synthesis of lactic acid by aerobic oxidation of glycerol on Au-Pt/TiO2 catalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 7368–7371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastalir, M.; Glatz, M.; Pittenauer, E.; Allmaier, G.; Kirchner, K. Sustainable Synthesis of Quinolines and Pyrimidines Catalyzed by Manganese PNP Pincer Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15543–15546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filonenko, G.A.; Van Putten, R.; Hensen, E.J.M.; Pidko, E.A. Catalytic (de)hydrogenation promoted by non-precious metals-Co, Fe and Mn: Recent advances in an emerging field. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 1459–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasolini, A.; Martelli, G.; Piazzi, A.; Curcio, M.; De Maron, J.; Basile, F.; Mazzoni, R. Advances in the Homogeneously Catalyzed Hydrogen Production from Biomass Derived Feedstocks: A Review. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202400393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostera, S.; Gonsalvi, L. Sustainable Hydrogen Production by Glycerol and Monosaccharides Catalytic Acceptorless Dehydrogenation (AD) in Homogeneous Phase. ChemSusChem 2024, 18, e202400639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Nielsen, M.; Li, B.; Dixneuf, P.H.; Junge, H.; Beller, M. Ruthenium-catalyzed hydrogen generation from glycerol and selective synthesis of lactic acid. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.; Das, K.; Prathapa, S.J.; Srivastava, H.K.; Kumar, A. Selective and high yield transformation of glycerol to lactic acid using NNN pincer ruthenium catalysts. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 9886–9889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, T.; Gong, H.; Ji, L.; Mao, J.; Xue, W.; Zheng, X.; Fu, H.; Chen, H.; Li, R.; Xu, J. Efficient co-upcycling of glycerol and CO2 into valuable products enabled by a bifunctional Ru-complex catalyst. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 12221–12224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.T.; Sinku, A.; Daw, P. A catalytic approach for the dehydrogenative upgradation of crude glycerol to lactate and hydrogen generation. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 37082–37086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, F.; Tung, N.T.; Fan, Y.; Li, F. Selective conversion of glycerol to potassium lactate and hydrogen gas in water catalyzed by a ruthenium complex bearing a functional ligand [(p-cymene)Ru(2-OH-6-BzlmHpy)Cl][Cl]. J. Catal. 2026, 453, 116442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccalon, E.; Menendez Rodriguez, G.; Trotta, C.; Ruffo, F.; Zuccaccia, C.; Macchioni, A. Acceptorless Dehydrogenation of Glycerol Catalysed by Ir(III) Complexes with Carbohydrate-Functionalised Ligands: A Sweet Pathway to Produce Hydrogen and Lactic Acid. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 27, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikas, N.; Kathuria, L.; Brodie, C.N.; Cross, M.J.; Pasha, F.A.; Weller, A.S.; Kumar, A. Selective PNP Pincer-Ir-Promoted Acceptorless Transformation of Glycerol to Lactic Acid and Hydrogen. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 3760–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisarya, A.; Dhole, S.; Kumar, A. Efficient net transfer-dehydrogenation of glycerol: NNN pincer-Mn and manganese chloride as a catalyst unlocks the effortless production of lactic acid and isopropanol. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 12698–12709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateshappa, B.; Bisarya, A.; Nandi, P.G.; Dhole, S.; Kumar, A. Production of Lactic Acid via Catalytic Transfer Dehydrogenation of Glycerol Catalyzed by Base Metal Salt Ferrous Chloride and Its NNN Pincer-Iron Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 15294–15310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharninghausen, L.S.; Mercado, B.Q.; Crabtree, R.H.; Hazari, N. Selective conversion of glycerol to lactic acid with iron pincer precatalysts. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 16201–16204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.Q.; Deng, J.; Fu, Y. Manganese-catalysed dehydrogenative oxidation of glycerol to lactic acid. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 8477–8483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, M.; Stöger, B.; Himmelbauer, D.; Veiros, L.F.; Kirchner, K. Chemoselective Hydrogenation of Aldehydes under Mild, Base-Free Conditions: Manganese Outperforms Rhenium. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4009–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgas, N.; Kirchner, K. Isoelectronic Manganese and Iron Hydrogenation/Dehydrogenation Catalysts: Similarities and Divergences. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 1558–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertini, F.; Gorgas, N.; Stöger, B.; Peruzzini, M.; Veiros, L.F.; Kirchner, K.; Gonsalvi, L. Efficient and Mild Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation to Formate Catalyzed by Fe(II) Hydrido Carbonyl Complexes Bearing 2,6-(Diaminopyridyl)diphosphine Pincer Ligands. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 2889–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertini, F.; Glatz, M.; Gorgas, N.; Stöger, B.; Peruzzini, M.; Veiros, L.F.; Kirchner, K.; Gonsalvi, L. Carbon dioxide hydrogenation catalysed by well-defined Mn(I) PNP pincer hydride complexes. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 5024–5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertini, F.; Glatz, M.; Stöger, B.; Peruzzini, M.; Veiros, L.F.; Kirchner, K.; Gonsalvi, L. Carbon Dioxide Reduction to Methanol Catalyzed by Mn(I) PNP Pincer Complexes under Mild Reaction Conditions. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostera, S.; Peruzzini, M.; Kirchner, K.; Gonsalvi, L. Mild and Selective Carbon Dioxide Hydroboration to Methoxyboranes Catalyzed by Mn(I) PNP Pincer Complexes. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 4625–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajitha, M.J.; Huang, K.-W. The Role of Substrate Acidity in PN3P–Ru Pincer Complex Catalyzed Formic Acid Dehydrogenation: Pseudo-Dearomatization vs Non-Dearomatization Pathways. Organometallics 2025, 44, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellone, I.; Gorgas, N.; Bertini, F.; Peruzzini, M.; Kirchner, K.; Gonsalvi, L. Selective Formic Acid Dehydrogenation Catalyzed by Fe-PNP Pincer Complexes Based on the 2,6-Diaminopyridine Scaffold. Organometallics 2016, 35, 3344–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, I.; Alobaid, N.A.; Menicucci, F.L.; Chakraborty, P.; Guan, C.; Han, D.; Huang, K.-W. Dehydrogenation of formic acid mediated by a Phosphorus–Nitrogen PN3P-manganese pincer complex: Catalytic performance and mechanistic insights. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 26559–26567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-Garagorri, D.; Becker, E.; Wiedermann, J.; Lackner, W.; Pollak, M.; Mereiter, K.; Kisala, J.; Kirchner, K. Achiral and chiral transition metal complexes with modularly designed tridentate PNP pincer-type ligands based on N-heterocyclic diamines. Organometallics 2006, 25, 1900–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parameterization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, V.; Cossi, M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossi, M.; Rega, N.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V. Energies, structures, and electronic properties of molecules in solution with the C-PCM solvation model. J. Comp. Chem. 2003, 24, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolg, M.; Stoll, H.; Preuss, H.; Pitzer, R.M. Relativistic and correlation-effects for element 105 (Hahnium, Ha): A comparative-study of M and MO (M = Nb, Ta, Ha) using energy-adjusted ab initio pseudopotentials. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 5852–5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | Cat. | Conv. b (%) | KLA b (%) | EG + FA b (%) | H2 c (ml) | TON d (KLA) | TON e (H2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | <1 | 10 | 10 |

| 2 | 2 | 77 | 77 | 0 | 18 | 385 | 385 |

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | <1 | 5 | 5 |

| 4 | PN3P-iPr | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | [RuCl2(PPh3)3] | 2 | 2 | 0 | <1 | 10 | 10 |

| 6 | None | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Entry | Solvent | Conv. b (%) | KLA (%) | EG + FA (%) | H2 c (ml) | TON d (KLA) | TON e (H2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NMP | 76 | 73 | 3 | 18 | 365 | 365 |

| 2 | NMP/H2O | 20 | 9 | 11 | 2 | 45 | 45 |

| 3 | Toluene | 23 | 20 | 3 | 5 | 100 | 100 |

| 4 | Dioxane | 27 | 13 | 14 | 3 | 65 | 65 |

| 5 | Neat | 23 | 20 | 3 | 5 | 100 | 115 |

| 6 | THF | 26 | 12 | 14 | 3 | 60 | 100 |

| 7 | EtOH | 77 | 77 | 0 | 18 | 385 | 374 |

| 8 | iPrOH | 17 | 17 | 0 | 4 | 85 | 85 |

| 9 | tBuOH | 60 | 57 | 3 | 14 | 285 | 285 |

| Entry | Base | Time (h) | Temp. (°C) | Conv. b (%) | KLA (%) | EG + FA (%) | H2 c (ml) | TON d (KLA) | TON e (H2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NaOMe | 24 | 140 | 37 | 31 | 6 | 7 | 155 | 155 |

| 2 | NaOH | 24 | 140 | 21 | 17 | 4 | 4 | 85 | 85 |

| 3 | NaOtBu | 24 | 140 | 18 | 18 | 0 | 4 | 90 | 90 |

| 4 | KOtBu | 24 | 140 | 85 | 80 | 5 | 19 | 400 | 400 |

| 5 | K2CO3 | 24 | 140 | 27 | 27 | 0 | 7 | 135 | 135 |

| 6 | DBU | 24 | 140 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | Et3N | 24 | 140 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | KOH | 48 | 140 | 82 | 80 | 2 | 18 | 400 | 374 |

| Entry | 2 (mol%) | Base | Conv. b (%) | KLA (%) | EG + FA (%) | H2 c (ml) | TON d (KLA) | TON e (H2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.2 | KOH | 77 | 77 | 0 | 18 | 385 | 385 |

| 2 | 0.05 | KOH | 86 | 80 | 6 | 19 | 1600 | 1600 |

| 3 | 0.2 | KOtBu | 85 | 80 | 5 | 19 | 400 | 400 |

| 4 | 0.02 | KOH | 18 | 18 | 0 | 4 | 900 | 900 |

| 5 | 0.05 | KOtBu | 9 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 180 | 180 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pal, S.; Kostera, S.; Manca, G.; Gonsalvi, L. Selective Production of Hydrogen and Lactate from Glycerol Dehydrogenation Catalyzed by a Ruthenium PN3P Pincer Complex. Catalysts 2026, 16, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010048

Pal S, Kostera S, Manca G, Gonsalvi L. Selective Production of Hydrogen and Lactate from Glycerol Dehydrogenation Catalyzed by a Ruthenium PN3P Pincer Complex. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010048

Chicago/Turabian StylePal, Saikat, Sylwia Kostera, Gabriele Manca, and Luca Gonsalvi. 2026. "Selective Production of Hydrogen and Lactate from Glycerol Dehydrogenation Catalyzed by a Ruthenium PN3P Pincer Complex" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010048

APA StylePal, S., Kostera, S., Manca, G., & Gonsalvi, L. (2026). Selective Production of Hydrogen and Lactate from Glycerol Dehydrogenation Catalyzed by a Ruthenium PN3P Pincer Complex. Catalysts, 16(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010048