Effect of Promoters on Co/Al2O3 Catalysts for Partial Oxidation of Methane: Structure–Activity Correlations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Catalysts

2.1.1. FT-IR Analysis

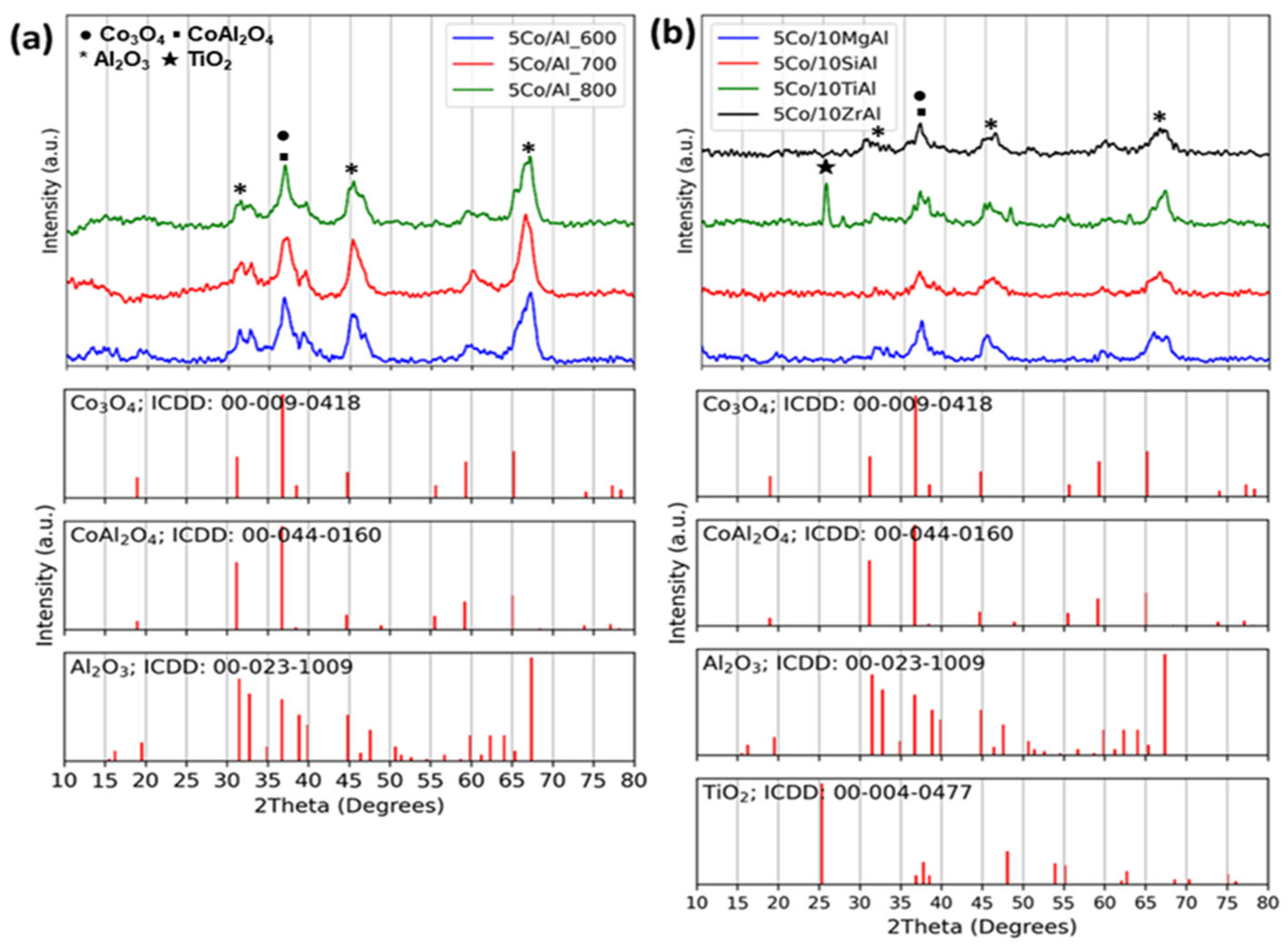

2.1.2. XRD Analysis of Catalysts

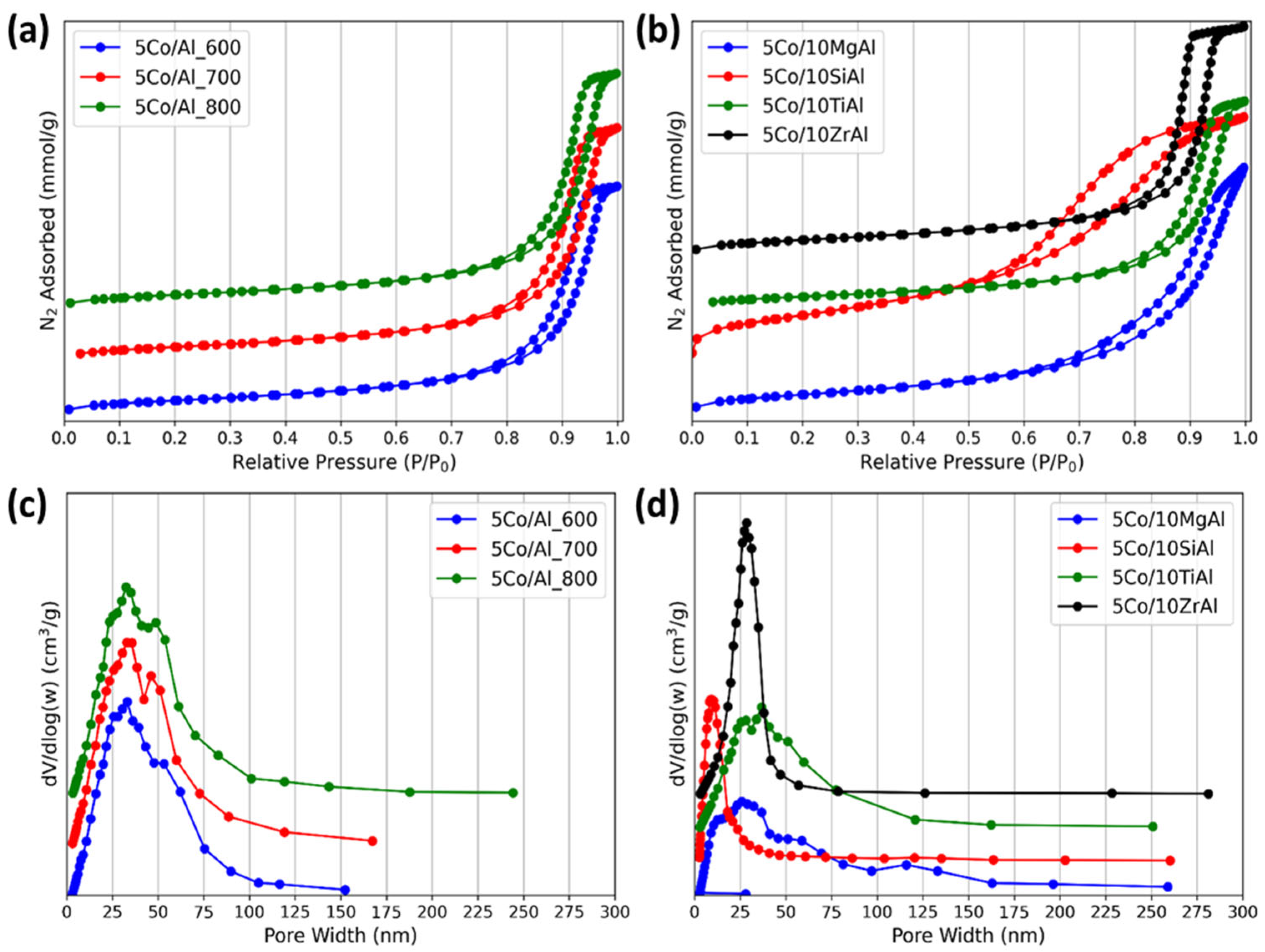

2.1.3. N2 Adsorption–Desorption Studies of Catalysts

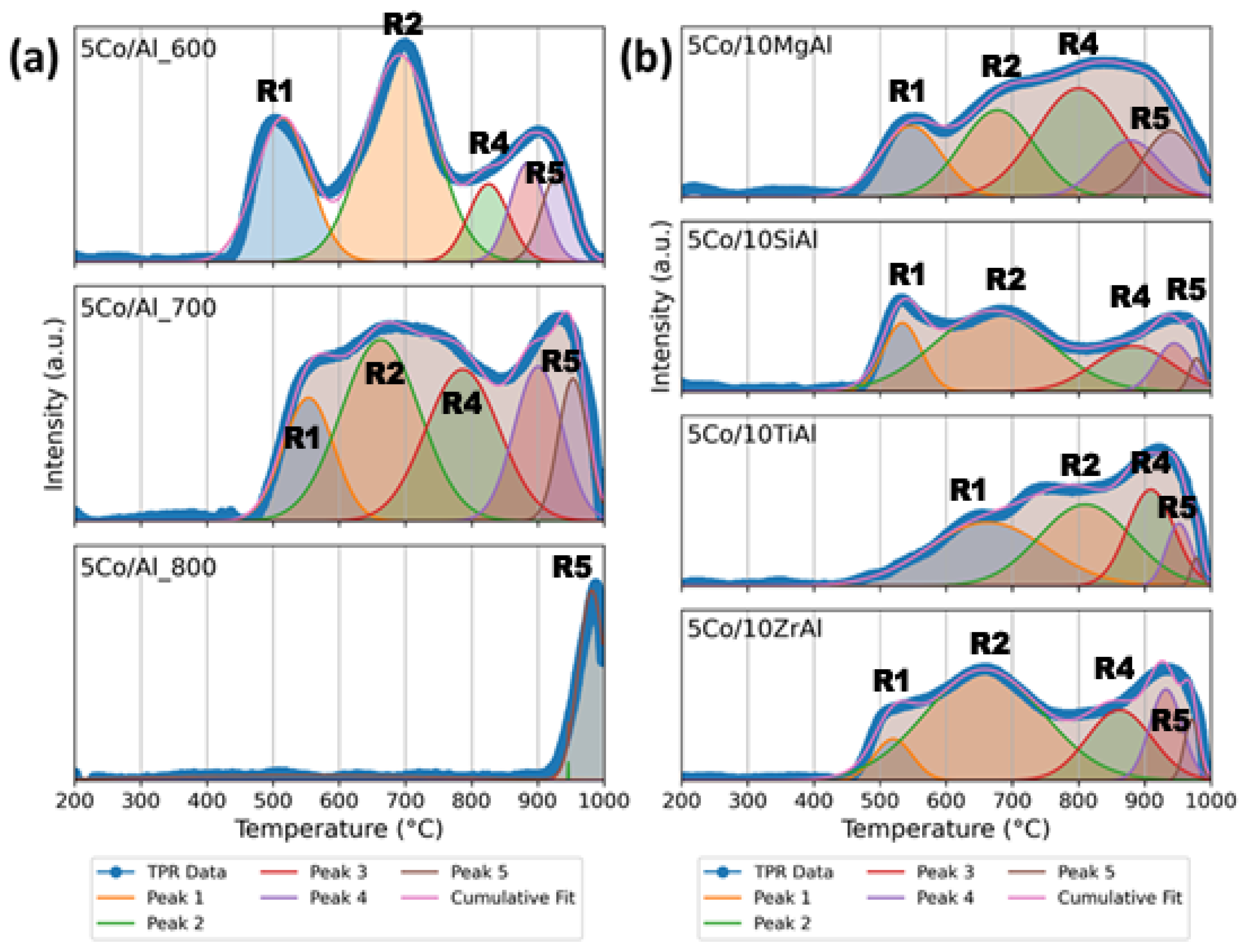

2.1.4. H2 Temperature Programmed Reduction (H2-TPR) Analysis of Catalysts

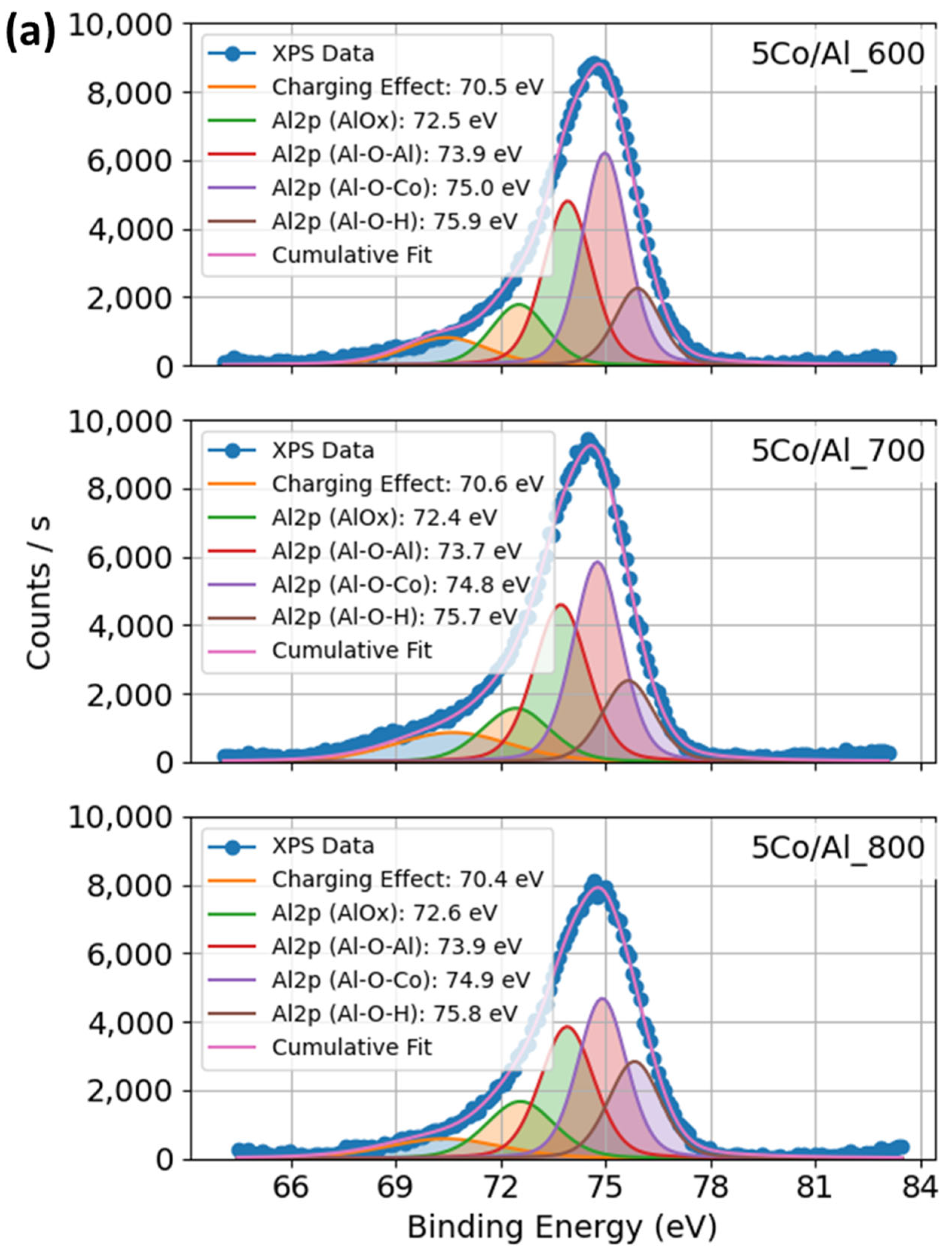

2.1.5. XPS Profiles of Co–Al–O System Under Calcination and Promoter Effects of Catalysts

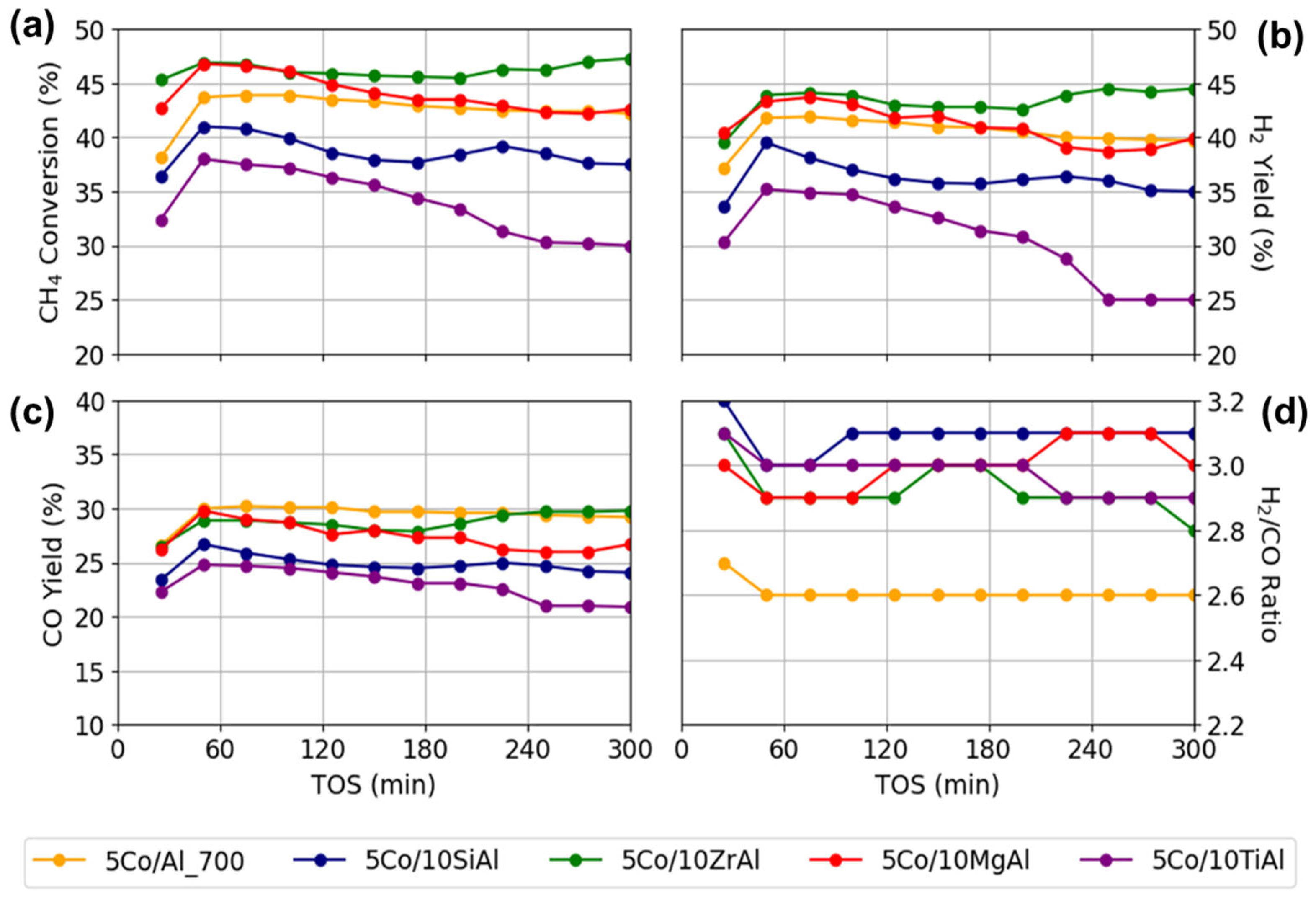

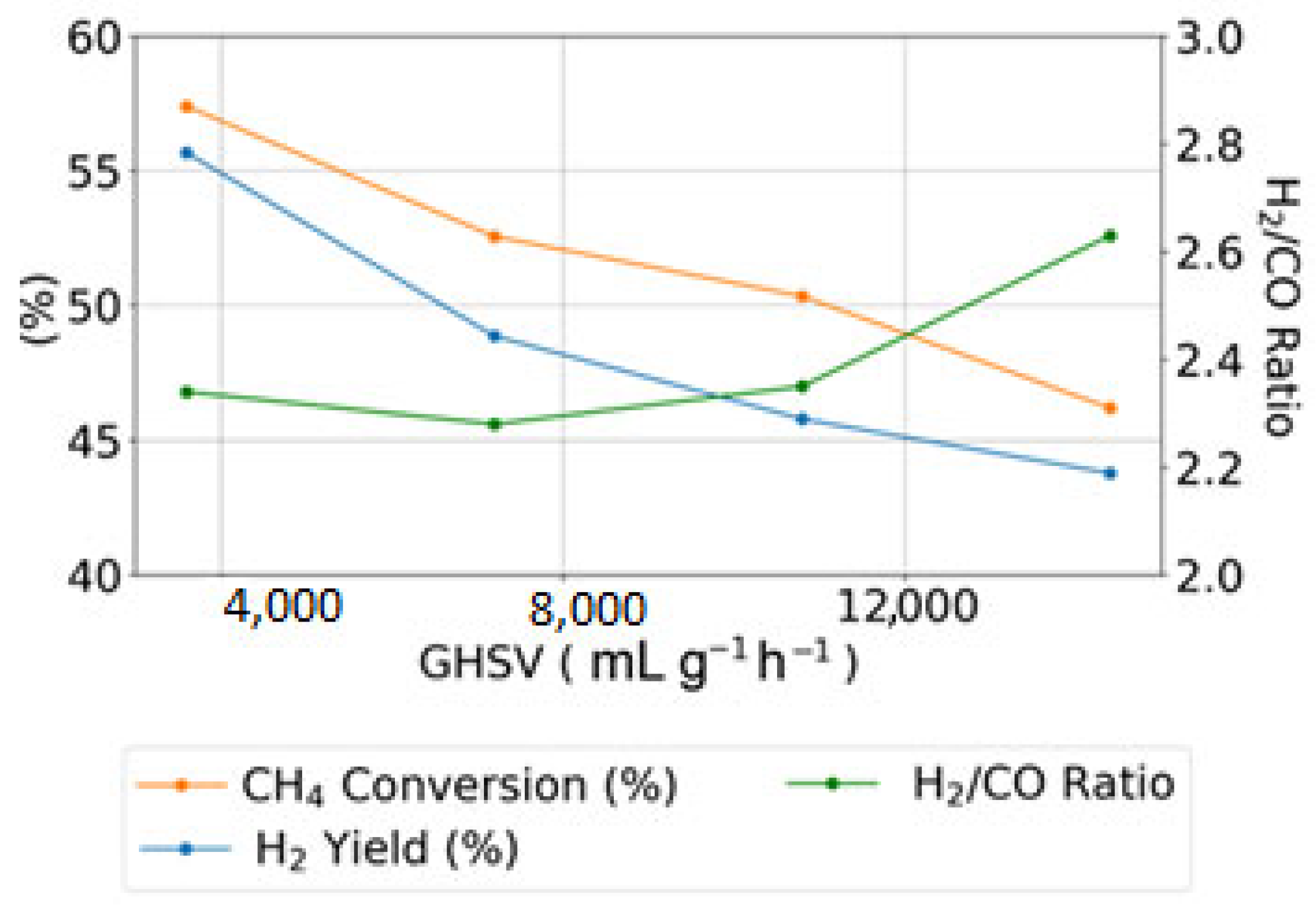

2.2. Catalyst Performance

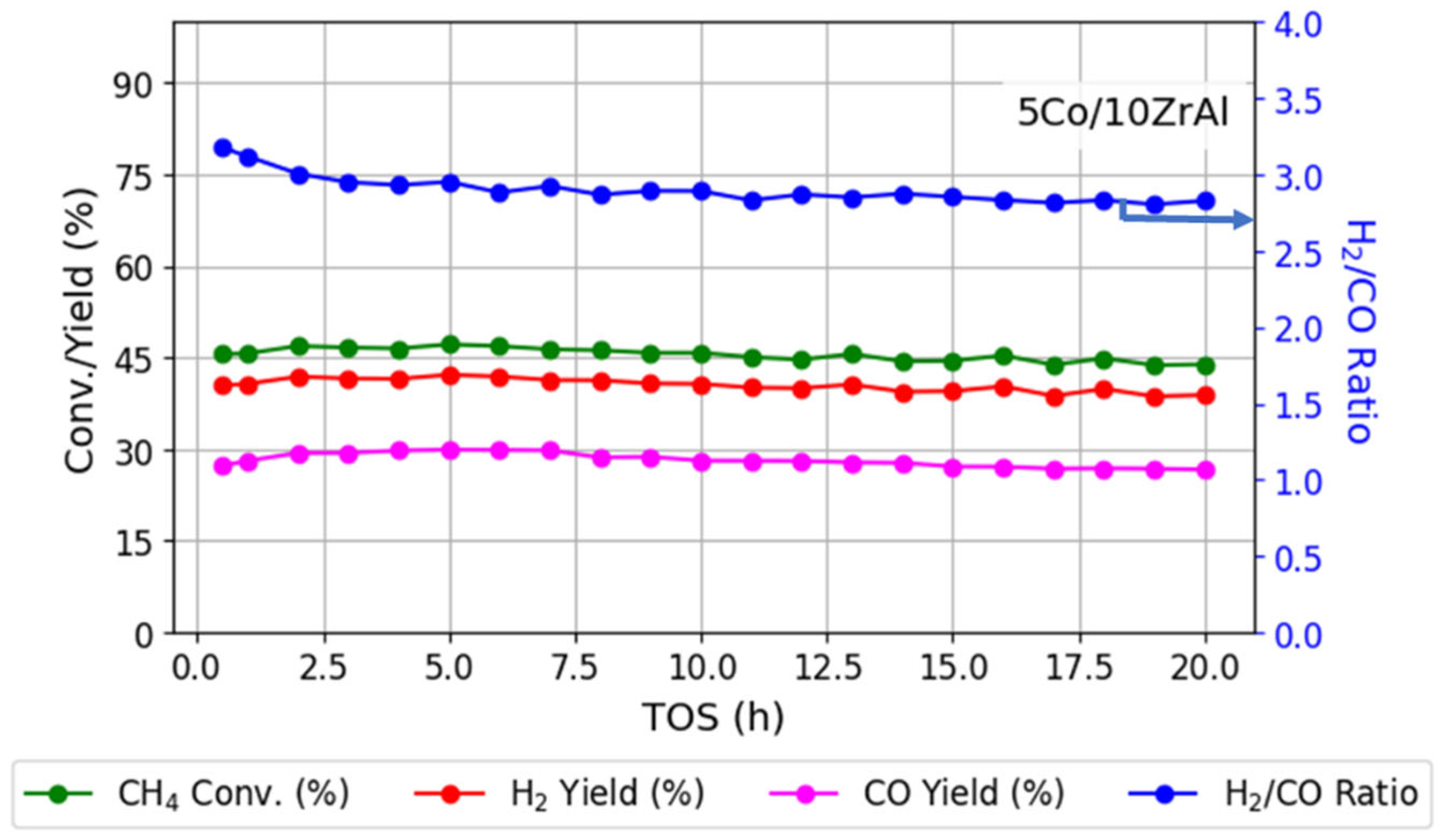

2.3. Stability Test of Catalyst

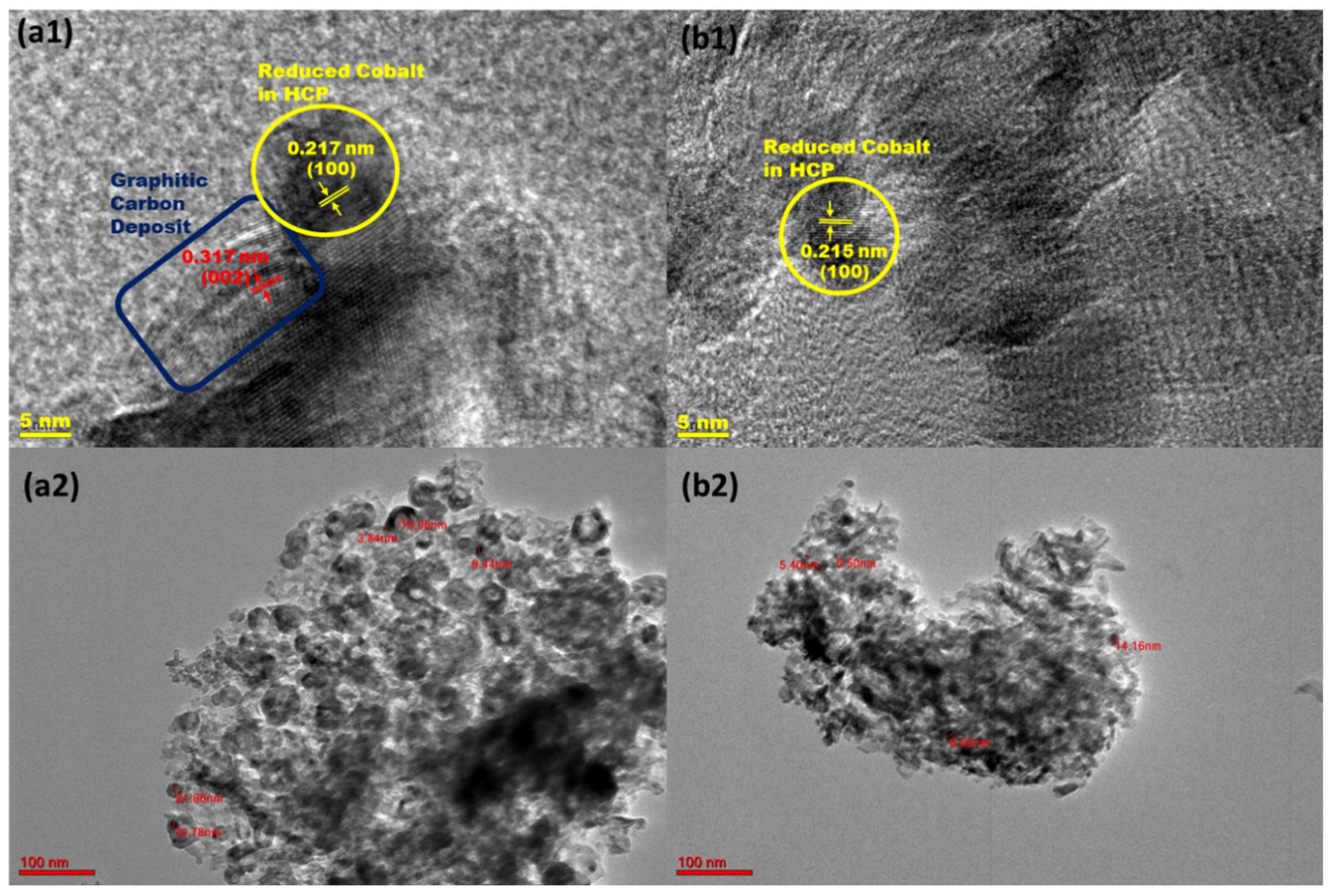

2.4. Analysis of Spent Catalysts

2.4.1. N2 Sorption Analysis of Spent Catalysts

2.4.2. TEM Analysis of Spent Catalysts

2.4.3. Raman Spectra of Spent Catalysts

2.4.4. Temperature Programmed Oxidation (O2-TPO) Analysis

2.4.5. TGA/DTG Characterization

2.5. Correlation of Physicochemical Properties with Catalytic Performance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of Unpromoted and Promoted Catalysts

3.3. Catalyst Activity Test

3.4. Catalyst Characterization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babakouhi, R.; Alavi, S.M.; Rezaei, M.; Akbari, E.; Varbar, M. Combined CO2 Reforming and Partial Oxidation of Methane over Mesoporous Nanostructured Ni/M-Al2O3 Catalyst: Effect of Various Support Promoters and Nickel Loadings. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 70, 102427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilicak Bayraktar, I.; Figen, H.E. Investigation of Partial Oxidation of Methane at Different Reaction Parameters by Adding Ni to CeO2 and ZrO2 Supported Cordierite Monolith Catalyst. Processes 2024, 12, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, A.P.E.; Xiao, T.; Green, M.L.H. Brief Overview of the Partial Oxidation of Methane to Synthesis Gas. Top. Catal. 2003, 22, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lu, Y.; Hong, Q.; Lin, J.; Dautzenberg, F.M. Catalytic Partial Oxidation of Methane to Syngas over Ca-Decorated-Al2O3-Supported Ni and NiB Catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2005, 292, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yang, M.; Huang, C.; Weng, W.; Wan, H. Partial Oxidation of Methane to Syngas over Mesoporous Co–Al2O3 Catalysts. Chin. J. Catal. 2013, 34, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, S.A.; Al-Abdrabalnabi, M.A.; Alanazi, A.A.; Al-Fatesh, A.S.; Fakeeha, A.H.; Awadallah, A.; Shaikh, H.M.; Kirchen, P. Hydrogen-Rich Syngas Production through Partial Oxidation of Methane over Ni-Promoted Molecular Sieves: Impact of Reducibility and Surface Area. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagaynov, I.V.; Loktev, A.S.; Arashanova, A.L.; Ivanov, V.K.; Dedov, A.G.; Moiseev, I.I. Ni(Co)–Gd0.1Ti0.1Zr0.1Ce0.7O2 Mesoporous Materials in Partial Oxidation and Dry Reforming of Methane into Synthesis Gas. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 290, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreshaidan, S.B.; Alanazi, R.S.A.; Odhah, O.H.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Ali, F.A.A.; Alarifi, N.; Banabdwin, K.M.; Ramesh, S.; Al-Fatesh, A.S. The Impact of Sm Promoter on the Catalytic Performance of Ni/Al2O3–SiO2 in Methane Partial Oxidation for Enhanced H2 Production. Catalysts 2025, 15, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ge, Z.; Zhu, G.; Wang, Z.; Ashok, J.; Kawi, S. Anti-Coking and Anti-Sintering Ni/Al2O3 Catalysts in the Dry Reforming of Methane: Recent Progress and Prospects. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Huang, C.; Zhu, X.; Xu, J.; Weng, W.; Wan, H. Effect of Calcination Temperature and Pretreatment with Reaction Gas on Properties of Co/γ-Al2O3 Catalysts for Partial Oxidation of Methane. Chem. Asian J. 2012, 7, 1895–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbadawi, A.H.; Ge, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Z. Catalytic Partial Oxidation of Methane to Syngas: Review of Perovskite Catalysts and Membrane Reactors. Catal. Rev. 2021, 63, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Sengupta, S.; Deo, G. Effect of Calcination Temperature during the Synthesis of Co/Al2O3 Catalyst Used for the Hydrogenation of CO2. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2013, 110, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadodaria, D.M.; Al-Fatesh, A.S.; Alrashed, M.M.; Alhoshan, M.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Kumar, N.S.; Kumar, R. A comprehensive review on catalytic oxidation of methane in the presence of molecular oxygen: Total oxidation, partial oxidation and selective oxidation. Catal. Rev. 2025, 67, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, G.; Ma, W.; Davis, B. Influence of Reduction Promoters on Stability of Cobalt/γ-Alumina Fischer–Tropsch Synthesis Catalysts. Catalysts 2014, 4, 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.X.; Huang, C.J.; Zhang, N.W.; Li, J.H.; Weng, W.Z.; Wan, H.L. Partial Oxidation of Methane to Synthesis Gas over Co/Ca/Al2O3 Catalysts. Catal. Today 2008, 131, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choya, A.; De Rivas, B.; González-Velasco, J.R.; Gutiérrez-Ortiz, J.I.; López-Fonseca, R. On the Beneficial Effect of MgO Promoter on the Performance of Co3O4/Al2O3 Catalysts for Combustion of Dilute Methane. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2019, 582, 117099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, J.; Garcilaso, V.; Venezia, B.; Aho, A.; Odriozola, J.A.; Boutonnet, M.; Järås, S. Fischer–Tropsch Synthesis over Zr-Promoted Co/γ-Al2O3 Catalysts. Top. Catal. 2017, 60, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, R.S.A.; Alreshaidan, S.B.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Wazeer, I.; Alarifi, N.; Bellahwel, O.A.; Abasaeed, A.E.; Al-Fatesh, A.S. Influence of alumina and silica supports on the performance of nickel catalysts for methane partial oxidation. Catalysts 2025, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Marie, A.; Griboval-Constant, A.; Khodakov, A.Y.; Diehl, F. Cobalt supported on alumina and silica-doped alumina: Catalyst structure and catalytic performance in Fischer–Tropsch synthesis. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2009, 12, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enger, B.C.; Lødeng, R.; Holmen, A. Modified Cobalt Catalysts in the Partial Oxidation of Methane at Moderate Temperatures. J. Catal. 2009, 262, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enger, B.C.; Lødeng, R.; Holmen, A. A Review of Catalytic Partial Oxidation of Methane to Synthesis Gas with Emphasis on Reaction Mechanisms over Transition Metal Catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2008, 346, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.A.; Khan, W.U.; Al-Mubaddel, F.; Al-Fatesh, A.S.; Kasim, S.O.; Mahmud, S.L.; Al-Zahrani, A.A.; Siddiqui, M.R.H.; Fakeeha, A.H. Study of Partial Oxidation of Methane by Ni/Al2O3 Catalyst: Effect of Support Oxides of Mg, Mo, Ti and Y as Promoters. Molecules 2020, 25, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Ponnada, S.; Enjamuri, N.; Pandey, J.K.; Chowdhury, B. Synthesis, Characterization and Correlation with the Catalytic Activity of Efficient Mesoporous Niobia and Mesoporous Niobia–Zirconia Mixed Oxide Catalyst System. Catal. Commun. 2016, 77, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damyanova, S.; Grange, P.; Delmon, B. Surface Characterization of Zirconia-Coated Alumina and Silica Carriers. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 1996, 101, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sako, E.Y.; Braulio, M.A.L.; Zinngrebe, E.; Van Der Laan, S.R.; Pandolfelli, V.C. Fundamentals and Applications on In Situ Spinel Formation Mechanisms in Al2O3–MgO Refractory Castables. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 2243–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardkhe, M.K.; Huang, B.; Bartholomew, C.H.; Alam, T.M.; Woodfield, B.F. Synthesis and Characterization of Silica Doped Alumina Catalyst Support with Superior Thermal Stability and Unique Pore Properties. J. Porous Mater. 2016, 23, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-W. The Mechanism of Reduction of Cobalt by Hydrogen. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2004, 85, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Duan, A.; Jiang, G.; Liu, J. Comparative Study on the Formation and Reduction of Bulk and Al2O3-Supported Cobalt Oxides by H2-TPR Technique. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 7186–7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirijaruphan, A.; Horváth, A.; Goodwin, J.G.; Oukaci, R. Cobalt Aluminate Formation in Alumina-Supported Cobalt Catalysts: Effects of Cobalt Reduction State and Water Vapor. Catal. Lett. 2003, 91, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeberle, J.; Henkel, K.; Gargouri, H.; Naumann, F.; Gruska, B.; Arens, M.; Tallarida, M.; Schmeißer, D. Ellipsometry and XPS Comparative Studies of Thermal and Plasma Enhanced Atomic Layer Deposited Al2O3-Films. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2013, 4, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, J.R.; Rose, H.J.; Swartz, W.E.; Watts, P.H.; Rayburn, K.A. X-ray Photoelectron Spectra of Aluminum Oxides: Structural Effects on the “Chemical Shift”. Appl. Spectrosc. 1973, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wong, L.; Tang, L.; Scarlett, N.V.; Chiang, K.; Patel, J.; Burke, N.; Sage, V. Kinetic Modelling of Temperature-Programmed Reduction of Cobalt Oxide by Hydrogen. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2017, 537, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, A.; Penki, T.R.; Munichandraiah, N.; Shivashankar, S.A. Flower-Like Porous Cobalt (II) Monoxide Nanostructures as Anode Material for Li-Ion Batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 761, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitten, A.; Guo, D.; Tezel, E.; Denecke, R.; Nikolla, E.; McEwen, J.-S. Deconvoluting XPS Spectra of La-Containing Perovskites from First-Principles. JACS Au 2024, 4, 3104–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, R.; Huo, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, L. Formation, Detection, and Function of Oxygen Vacancy in Metal Oxides for Solar Energy Conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2109503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supat, K.; Chavadej, S.; Lobban, L.L.; Mallinson, R.G. Combined Steam Reforming and Partial Oxidation of Methane to Synthesis Gas under Electrical Discharge. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 1654–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepamatr, P.; Rungsri, P.; Daorattanachai, P.; Laosiripojana, N. Maximizing H2 Production from a Combination of Catalytic Partial Oxidation of CH4 and Water Gas Shift Reaction. Molecules 2025, 30, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittich, K.; Krämer, M.; Bottke, N.; Schunk, S.A. Catalytic Dry Reforming of Methane: Insights from Model Systems. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 2130–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, D.A.; Schmidt, L.D. Production of Syngas by Direct Catalytic Oxidation of Methane. Science 1993, 259, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khader, M.M. Effects of Support on Ni-Based Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane. Catal. Lett. 2025, 11, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeeha, A.H.; Osman, A.I.; Al-Fatesh, A.S.; Al-Awadi, A.S.; Alrasheed, R.A.; Al-Ayed, O.S.; Al-Faifi, N.H.; Kumar, R. Highly Selective Syngas/H2 Production via Partial Oxidation of CH4 Using (Ni, Co and Ni–Co)/ZrO2–Al2O3 Catalysts: Influence of Calcination Temperature. Processes 2019, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Minh, C.; Li, C.; Brown, T. Kinetics of coke combustion during temperature-programmed oxidation of deactivated cracking catalysts. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 1997, 111, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cui, Y.; Si-Ma, W.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Q. Advances and Challenges in Oxygen Carriers for Chemical Looping Partial Oxidation of Methane. Catalysts 2024, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalysts | BET Surface Area (m2 g−1) | Pore Volume (cm3 g−1) | Average Pore Diameter (nm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Desorption | Adsorption | Desorption | ||

| 5Co/Al_600 | 125 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 19.79 | 17.27 |

| 5Co/Al_700 | 126 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 19.84 | 17.17 |

| 5Co/Al_800 | 118 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 21.20 | 18.15 |

| 5Co/10MgAl | 162 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 15.36 | 13.55 |

| 5Co/10SiAl | 322 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 7.89 | 6.94 |

| 5Co/10TiAl | 109 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 20.31 | 17.69 |

| 5Co/10ZrAl | 128 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 19.59 | 16.08 |

| Catalyst | Peak 1 | Peak 2 | Peak 3 | Peak 4 | Peak 5 | H2 Consumed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp (°C) | Area (%) | Temp (°C) | Area (%) | Temp (°C) | Area (%) | Temp (°C) | Area (%) | Temp (°C) | Area (%) | (µmol g−1) | |

| 5Co/Al_600 | 514.9 | 24.90 | 691.8 | 46.55 | 825.7 | 10.04 | 884.7 | 11.02 | 929.7 | 7.49 | 851 |

| 5Co/Al_700 | 553.7 | 14.47 | 662.5 | 33.08 | 786.5 | 25.86 | 900.8 | 17.14 | 953.3 | 9.45 | 944 |

| 5Co/Al_800 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 981.8 | 100 | 149 |

| 5Co/10MgAl | 547.1 | 16.19 | 677.8 | 23.79 | 800.6 | 34.98 | 878.0 | 12.94 | 938.8 | 12.10 | 831 |

| 5Co/10SiAl | 533.8 | 14.89 | 670.4 | 52.74 | 882.4 | 19.85 | 944.6 | 9.88 | 978.5 | 2.63 | 595 |

| 5Co/10TiAl | 662.5 | 35.04 | 810.3 | 35.24 | 909.3 | 21.00 | 951.8 | 7.42 | 977.8 | 1.29 | 556 |

| 5Co/10ZrAl | 520.1 | 6.84 | 657.5 | 56.74 | 861.9 | 19.77 | 932.3 | 12.78 | 969.8 | 3.87 | 892 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Banabdwin, K.M.; Abahussain, A.A.M.; BaQais, A.; Bhran, A.A.; Saeed, A.M.M.; Alotaibi, N.N.; Al Sudairi, M.A.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Singh, S.K.; Al-Fatesh, A.S. Effect of Promoters on Co/Al2O3 Catalysts for Partial Oxidation of Methane: Structure–Activity Correlations. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121176

Banabdwin KM, Abahussain AAM, BaQais A, Bhran AA, Saeed AMM, Alotaibi NN, Al Sudairi MA, Ibrahim AA, Singh SK, Al-Fatesh AS. Effect of Promoters on Co/Al2O3 Catalysts for Partial Oxidation of Methane: Structure–Activity Correlations. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121176

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanabdwin, Khaled M., Abdulaziz A. M. Abahussain, Amal BaQais, Ahmed A. Bhran, Alaaddin M. M. Saeed, Nawaf N. Alotaibi, Mohammed Abdullh Al Sudairi, Ahmed A. Ibrahim, Sunit Kumar Singh, and Ahmed S Al-Fatesh. 2025. "Effect of Promoters on Co/Al2O3 Catalysts for Partial Oxidation of Methane: Structure–Activity Correlations" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121176

APA StyleBanabdwin, K. M., Abahussain, A. A. M., BaQais, A., Bhran, A. A., Saeed, A. M. M., Alotaibi, N. N., Al Sudairi, M. A., Ibrahim, A. A., Singh, S. K., & Al-Fatesh, A. S. (2025). Effect of Promoters on Co/Al2O3 Catalysts for Partial Oxidation of Methane: Structure–Activity Correlations. Catalysts, 15(12), 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121176