Alkylation of Benzene with Benzyl Chloride: Comparative Study Between Commercial MOFs and Metal Chloride Catalysts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Reaction Studies

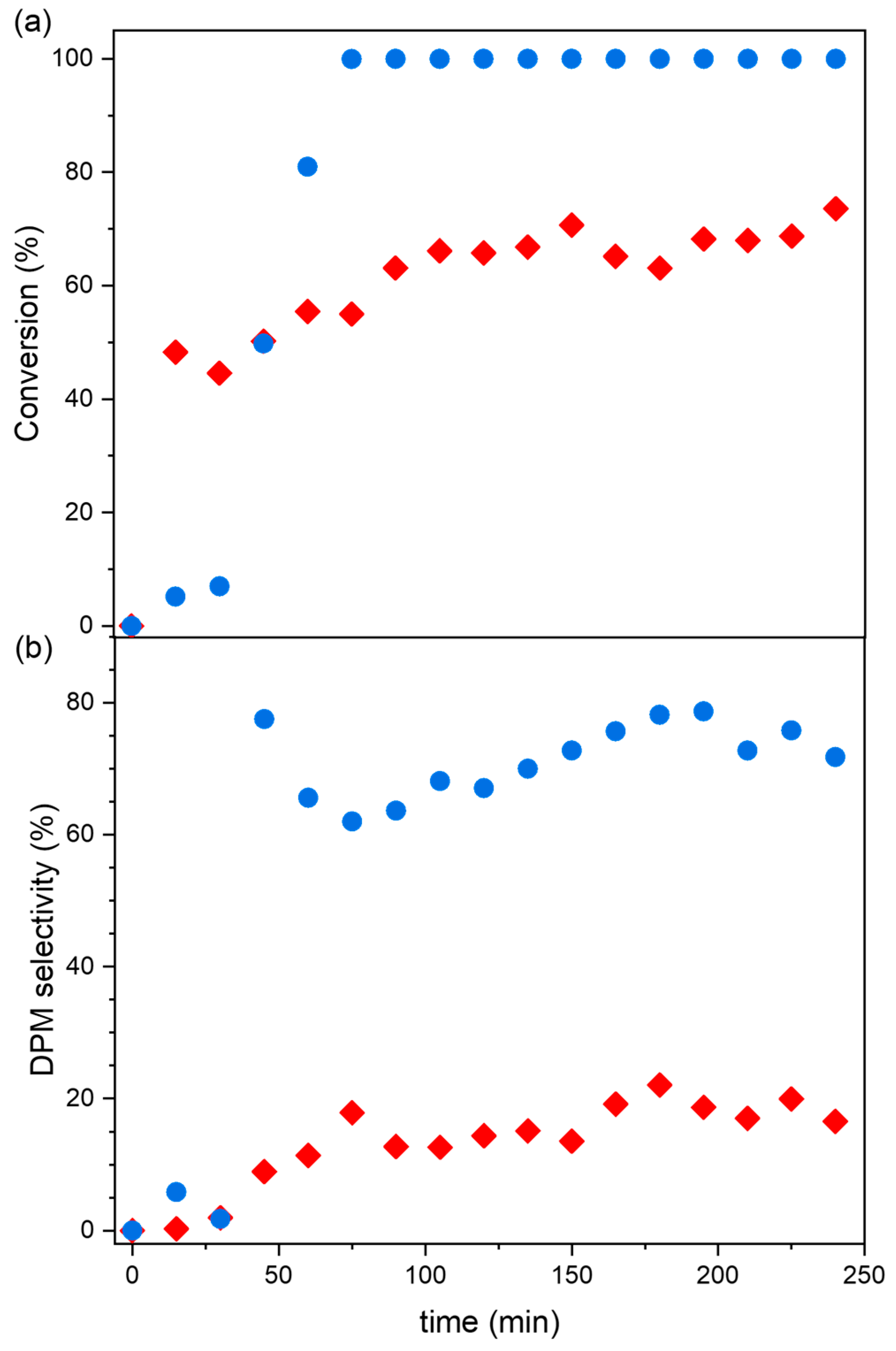

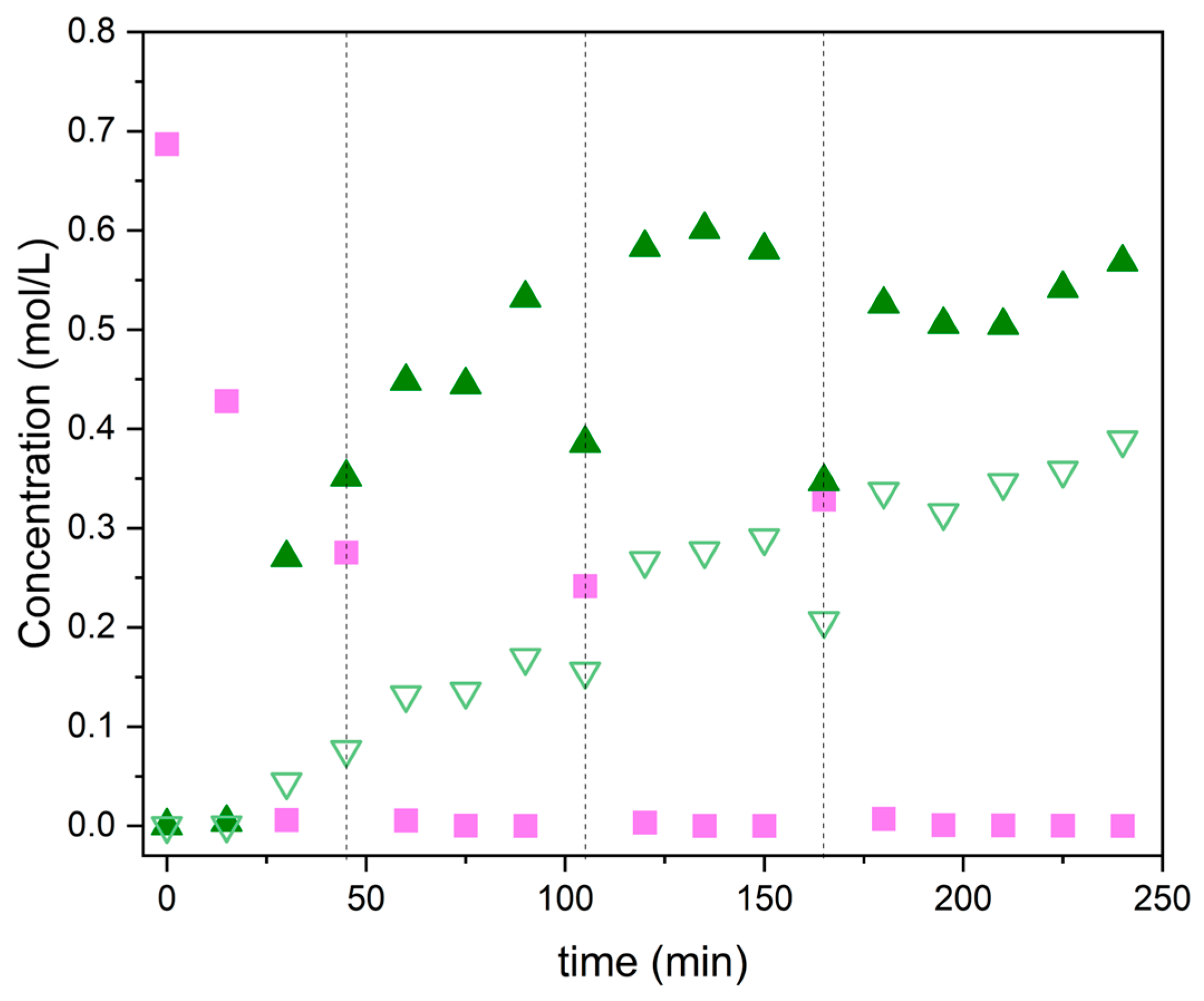

2.1.1. Commercial Metal–Organic Frameworks for Benzene Benzylation with Benzyl Chloride

2.1.2. Catalytic Performance Comparison with Metal Chloride Catalysts and Reported Heterogeneous Catalysts

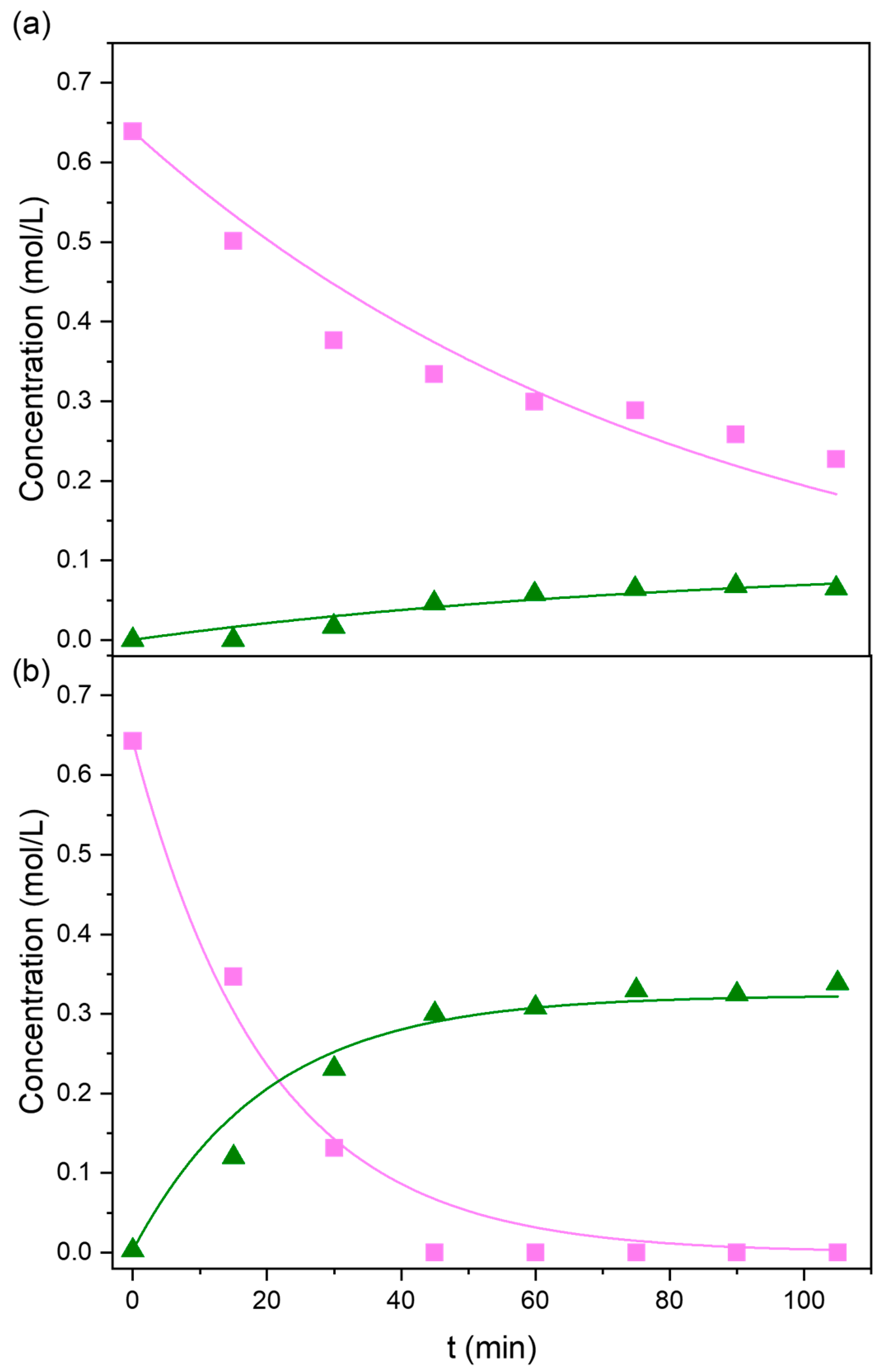

2.2. Kinetic Modeling

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Catalysts and Chemicals

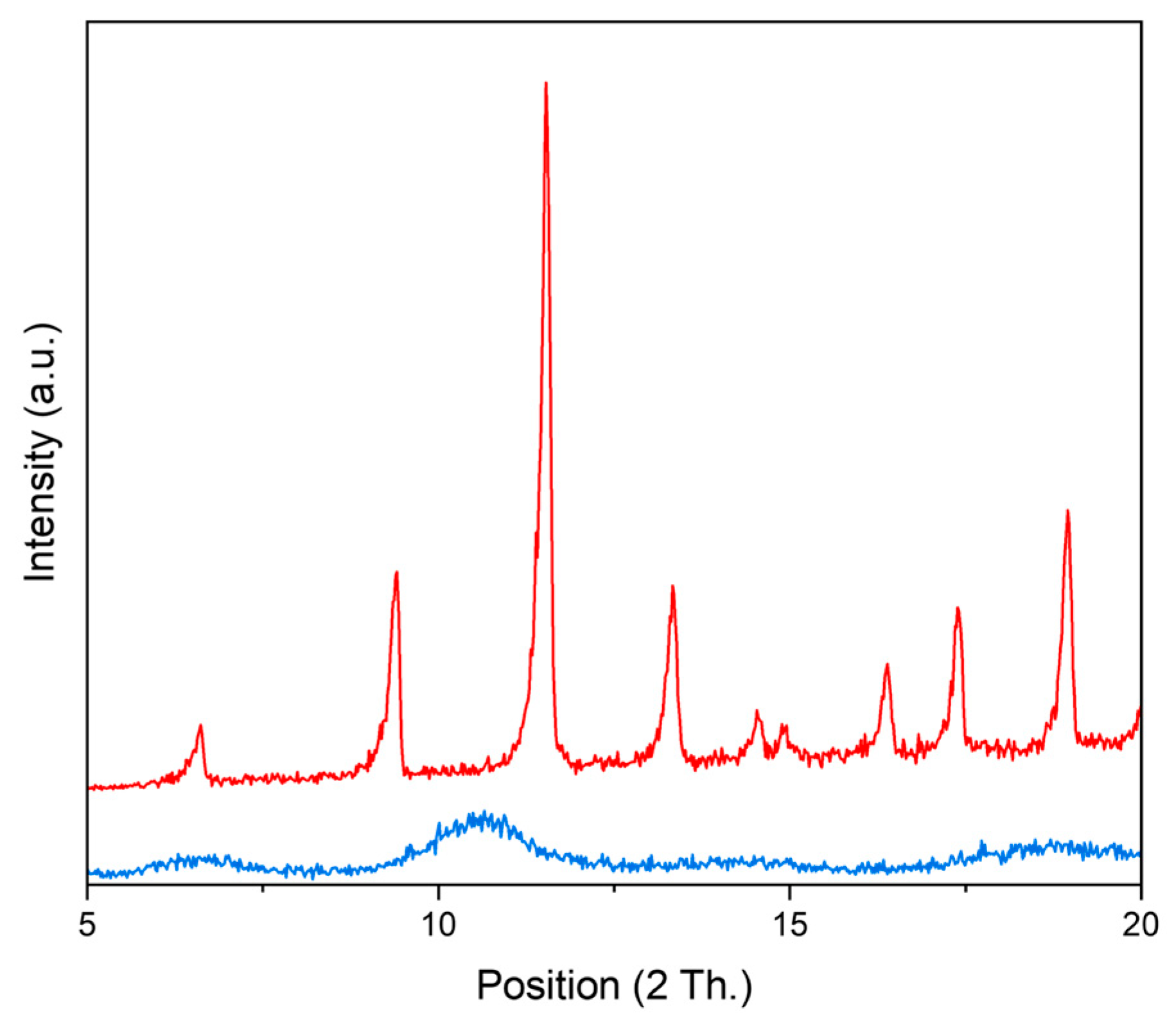

3.2. Catalysts Characterization

3.3. Reaction Analysis

3.4. Analytical and Characterization Techniques

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B | Benzene |

| BC | Benzyl chloride |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| BJH | Barrett–Joyner–Halenda |

| BTC | 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid |

| DPM | Diphenylmethane |

| DTG | Derivative thermogravimetric |

| FID | Flame ionization detector |

| GC | Gas chromatograph |

| ICP-MS | Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| LOHC | Liquid organic hydrogen carrier |

| M | Metal |

| MOFs | Metal–organic frameworks |

| MS | Mass spectrometer |

| PCB | Polychlorinated biphenyls |

| Pair distribution function | |

| TG | Thermogravimetric |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| TOR | Turn-over rate |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Li, S.; Han, Q.; Ma, Y.-Y.; Zhang, S.-M.; Du, J.; Han, Z.-G. Polyoxometalate-encapsulated copper-organic complexes for efficient C-H bond oxidation of alkylbenzenes. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1342, 142686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Griesbaum, K.; Behr, A.; Biedenkapp, D.; Voges, H.-W.; Garbe, D.; Paetz, C.; Collin, G.; Mayer, D.; Höke, H.; et al. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, C.; Priya, S.V.; Lawrence, G.; Dhawale, D.S.; Varghese, S.; Wahab, M.A.; Prasad, K.S.; Vinu, A. Cage type mesoporous ferrosilicate catalysts with 3D structure for benzylation of aromatics. Catal. Today 2013, 204, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, E.; Ordóñez, S.; Vega, A.; Auroux, A.; Coca, J. Benzylation of benzene over Fe-modified ZSM-5 zeolites: Correlation between activity and adsorption properties. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2005, 295, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, A.; Alhamed, Y. Catalytic activity of mesoporous catalysts in Friedel–Crafts benzylation of benzene. J. Porous Mat. 2009, 16, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Diaz, E.; Rapado-Gallego, P.; Ordóñez, S. Systematic evaluation of physicochemical properties for the selection of alternative liquid organic hydrogen carriers. J. Energy Storage 2023, 59, 106511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhani, S.; Dao, Q.N.; Imanuel, Y.; Ridwan, M.; Sohn, H.; Jeong, H.; Kim, K.; Yoon, C.W.; Song, K.H.; Kim, Y. Advances in catalytic hydrogenation of liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs) using high-purity and low-purity hydrogen. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202401278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavati-Niasari, M.; Hasanalian, J.; Najafian, H. Alumina-supported FeCl3, MnCl2, CoCl2, NiCl2, CuCl2, and ZnCl2 as catalysts for the benzylation of benzene by benzyl chloride. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2004, 209, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, K.; Sun, S.; Wang, B.; Sun, L.; Xu, W.; Sun, Y. Benzylation of benzene with benzyl chloride on iron-containing mesoporous mordenite. Catal. Commun. 2012, 28, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.R.; Jana, S.K.; Kiran, B.P. Alkylation of benzene by benzyl chloride over H-ZSM-5 zeolite with its framework Al completely or partially substituted by Fe or Ga. Catal. Lett. 1999, 59, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.R.; Jana, S.K.; Mamman, A.S. Benzylation of benzene by benzyl chloride over Fe-modified ZSM-5 and H-β zeolites and Fe2O3 or FeCl3 deposited on micro-, meso- and macro-porous supports. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 2002, 56, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.R.; Jana, S.K. Benzylation of benzene by benzyl chloride over Fe-, Zn-, Ga- and In-modified ZSM-5 type zeolite catalysts. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2002, 224, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyande, S.N.; Jaiswal, R.G.; Jayaram, R.V. Reaction kinetics of benzylation of benzene with benzyl chloride on sulfate-treated metal oxide catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1998, 37, 908–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-S.; Ahn, W.-S. Diphenylmethane synthesis using ionic liquids as lewis acid catalyst. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2003, 20, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachari, K.; Millet, J.M.M.; Benaïchouba, B.; Cherifi, O.; Figueras, F. Benzylation of benzene by benzyl chloride over iron mesoporous molecular sieves materials. J. Catal. 2004, 221, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachter, E.R.; Pinto, M.M.; Marques, M.R.C. Alkylation of benzene with alcohols and benzyl chloride catalyzed by ion exchange resins. React. Polym. 1991, 15, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.R.; Jana, S.K. Benzylation of benzene and substituted benzenes by benzyl chloride over InCl3, GaCl3, FeCl3 and ZnCl2 supported on clays and Si-MCM-41. J. Mol. Catal. A-Chem. 2002, 180, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cseri, T.; Békássy, S.; Figueras, F.; Rizner, S. Benzylation of aromatics on ion-exchanged clays. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 1995, 98, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.T.; Narasimharao, K.; Ahmed, N.S.; Basahel, S.; Al-Thabaiti, S.; Mokhtar, M. Nanosized iron and nickel oxide zirconia supported catalysts for benzylation of benzene: Role of metal oxide support interaction. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2014, 486, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horcajada, P.; Surblé, S.; Serre, C.; Hong, D.-Y.; Seo, Y.-K.; Chang, J.-S.; Grenèche, J.-M.; Margiolaki, I.; Férey, G. Synthesis and catalytic properties of MIL-100(Fe), an iron(iii) carboxylate with large pores. Chem. Commun. 2007, 27, 2820–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentit, H.; Bachari, K.; Ouali, M.S.; Womes, M.; Benaichouba, B.; Jumas, J.C. Alkylation of benzene and other aromatics by benzyl chloride over iron-containing aluminophosphate molecular sieves. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2007, 275, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakshinamoorthy, A.; Li, Z.; Garcia, H. Catalysis and photocatalysis by metal organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 8134–8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ma, J.-G.; Cheng, P. Constructing high-performance heterogeneous catalysts through interface engineering on metal–organic framework platforms. Acc. Mater. Res. 2025, 6, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, N.T.S.; Le, K.K.A.; Phan, T.D. MOF-5 as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for Friedel–Crafts alkylation reactions. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2010, 382, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.L.; Nguyen, C.V.; Dang, G.H.; Le, K.K.A.; Phan, N.T.S. Towards applications of metal–organic frameworks in catalysis: Friedel–Crafts acylation reaction over IRMOF-8 as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2011, 349, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, E.; Rahmani, M. Al-based MIL-53 metal organic framework (MOF) as the new catalyst for Friedel–Crafts alkylation of benzene. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, E.; Rahmani, M. Alkylation of benzene over Fe-based metal organic frameworks (MOFs) at low temperature condition. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 2017, 249, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.S.; Sivakumar, B.; Rokhum, S.L.; Biswas, S.; Cirujano, F.G.; Dhakshinamoorthy, A. Engineering of active sites in Metal-Organic Frameworks for Friedel–Crafts alkylation. ChemCatChem 2025, 17, e202401477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-H.; Kong, F.; Liu, B.-F.; Ren, N.-Q.; Ren, H.-Y. Preparation strategies of waste-derived MOF and their applications in water remediation: A systematic review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 533, 216534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Tang, C.; Wang, C.-C.; Zhao, C. From ore to MOF: A case of MIL-100(Fe) production from iron ore concentrates. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2024, 34, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guesh, K.; Caiuby, C.A.D.; Mayoral, Á.; Díaz-García, M.; Díaz, I.; Sanchez-Sanchez, M. Sustainable preparation of MIL-100(Fe) and its photocatalytic behavior in the degradation of methyl orange in water. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 1806–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapnik, A.F.; Ashling, C.W.; Macreadie, L.K.; Lee, S.J.; Johnson, T.; Telfer, S.G.; Bennett, T.D. Gas adsorption in the topologically disordered Fe-BTC framework. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 27019–27027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursueguía, D.; Díaz, E.; Ordóñez, S. Densification-induced structure changes in Basolite MOFs: Effect on low-pressure CH4 adsorption. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdy, M.S.; Mul, G.; Jansen, J.C.; Ebaid, A.; Shan, Z.; Overweg, A.R.; Mashmeyer, T. Synthesis, characterization, an unique catalytic performance of mesoporous Fe-TUD1 in Friedel-Crafts benzylation of benzene. Catal. Today 2005, 100, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autié-Castro, G.; Reguera, E.; Cavalcante, C.L.; Araujo, A.S.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E. Surface acid-base properties of Cu-BTC and Fe-BTC MOFs. An inverse gas chromatography and n-butylamine thermo desorption study. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 507, 119590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, C.; Srinivasu, P.; Alam, S.; Balasubramanian, V.V.; Sawant, D.P.; Palanichamy, M.; Murugesan, V.; Vinu, A. Highly active three-dimensional cage type mesoporous ferrosilicate catalysts for the Friedel–Crafts alkylation. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 2008, 111, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autie-Castro, G.; Autie, M.A.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Aguirre, C.; Reguera, E. Cu-BTC and Fe-BTC metal-organic frameworks: Role of the materials structural features on their performance for volatile hydrocarbons separation. Colloid Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2015, 481, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachari, K.; Cherifi, O. Benzylation of benzene and other aromatics by benzyl chloride over copper-mesoporous molecular sieves materials. Catal. Commun. 2006, 7, 926–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaube, V.D. Benzylation of benzene to diphenylmethane using zeolite catalysts. Catal. Commun. 2004, 5, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachari, K.; Cherifi, O. Study of the benzylation of benzene and other aromatics by benzyl chloride over transition metal chloride supported mesoporous SBA-15 catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2006, 260, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, J.T.; Willis, D.E. Calculation of flame ionization detector relative response factors using the effective carbon number concept. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 1985, 23, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tradename | Framework | SBET (m2/g) | Microporosity (m2/g) | Vmicropores (cm3/g) | Vmesopores (cm3/g) | Dp (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basolite F300 | Fe(BTC) | 962 | 645 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 5.8 |

| Basolite C300 | Cu3(BTC)2 | 1514 | 1268 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 3.2 |

| Catalyst | B:BC mol | M:BC mol | T (K) | t (h) | (%) | (%) | TOR (mmolBC/molM·s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu-based catalysts | ||||||||

| Basolite C300 | 15 | 0.010 | 353 | 0.67 | 50.2 | 16.8 | 20.2 | This work |

| Cu-HMS-25 | 15 | 0.003 | 353 | 0.75 | 50.0 | 69.6 | 68.0 | [38] |

| CuCl2/Al2O3 | 17 | 0.055 | 353 | 3.00 | 87.6 | 91.4 | 1.5 | [8] |

| Basolite C300 | 15 | 0.010 | 353 | 3.00 | 76.2 | 16.5 | 6.8 | This work |

| Fe-based catalysts | ||||||||

| FeCl3/Al2O3 | 17 | 0.055 | 353 | 3.00 | 98.4 | 97.6 | 1.6 | [8] |

| Basolite F300 | 15 | 0.010 | 353 | 1.25 | 100.0 | 72.0 | 22.2 | This work |

| MIL-100(Fe) | 10 | 0.038 | 343 | 0.28 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 26.0 | [20] |

| FeKIT-5(12) | 15 | 0.016 | 353 | 0.58 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 29.4 | [3] |

| Fe-M-MOR | 17 | 0.012 | 343 | 0.50 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 44.5 | [9] |

| Fe-ZSM-5 | 15 | 0.002 | 353 | 1.48 | 100.0 | 45.0 | 78.5 | [4] |

| Fe-HMS-50 | 15 | 0.002 | 353 | 2.00 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 87.7 | [15] |

| Homogeneous catalysts | ||||||||

| AlCl3 | 3 | 0.094 | 358 | 0.50 | 100.0 | 58.0 | 5.9 | [39] |

| CuCl2 | 19 | 0.086 | 353 | 0.86 | 90.0 | 43.8 | 3.4 | [40] |

| FeCl3 | 19 | 0.071 | 353 | 0.51 | 90.0 | 52.3 | 6.9 | [40] |

| Catalyst | k1 103 (min−1) | k2 103 (min−1) | k3 105 (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basolite C300 | 1.84 | 10.0 | 0.64 |

| Basolite F300 | 25.0 | 25.1 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peláez, R.; Gutiérrez, I.; Díaz, E.; Ordóñez, S. Alkylation of Benzene with Benzyl Chloride: Comparative Study Between Commercial MOFs and Metal Chloride Catalysts. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111075

Peláez R, Gutiérrez I, Díaz E, Ordóñez S. Alkylation of Benzene with Benzyl Chloride: Comparative Study Between Commercial MOFs and Metal Chloride Catalysts. Catalysts. 2025; 15(11):1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111075

Chicago/Turabian StylePeláez, Raquel, Inés Gutiérrez, Eva Díaz, and Salvador Ordóñez. 2025. "Alkylation of Benzene with Benzyl Chloride: Comparative Study Between Commercial MOFs and Metal Chloride Catalysts" Catalysts 15, no. 11: 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111075

APA StylePeláez, R., Gutiérrez, I., Díaz, E., & Ordóñez, S. (2025). Alkylation of Benzene with Benzyl Chloride: Comparative Study Between Commercial MOFs and Metal Chloride Catalysts. Catalysts, 15(11), 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111075