Abstract

Photo(electro)-catalysis has increasingly attracted attention from researchers due to its wide applications in green chemical transformation, including organic synthesis and environmental remediation. As a promising candidate, the n-type semiconductor WO3 possesses a suitable bandgap (~2.6 eV), good visible-light response, high chemical stability, and multi-electron transfer capability, thus endowing it with enormous potential in heterogeneous photocatalysis (PC) and photoelectrocatalysis (PEC) to address environment and energy issues. In this review, the recent research progress of WO3-based photo(electro)-catalysts is examined and systematically summarized with regard to construction strategies and various application scenarios. To start with, the research background, functionalization methods and possible reaction mechanisms for WO3 are introduced in depth. Key influencing factors, including light absorption capacity, charge carrier separation, and reusability, are also analyzed. Then, diverse applications of WO3 for the elimination of organic pollutants (e.g., persistent organic pollutants and polymeric wastes) and green organic synthesis (i.e., oxidation, reduction, and other reactions) are intentionally discussed to underscore their vast potential in photo(electro)-catalytic performance. Finally, future challenges and insightful perspectives are proposed to explore effective WO3-based materials. This comprehensive review aims to offer profound insights into innovative exploration of high-performance WO3 semiconductor catalysts and guide new researchers in this field to better understand their vital roles in green organic synthesis and hazardous pollutants removal.

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of the global population, energy demands and environmental pollution have gradually emerged as two critical issues worldwide, given their inevitable adverse effects on human quality of life, health damage, and ecosystem destruction [1]. One of the most effective approaches to address these problems is to optimize energy mixes and improve utilization efficiency. However, traditional fossil fuels (e.g., coal, oil, and natural gas) face the issues of finite availability, low energy conversion efficiency, and discharge of massive wastes, so a transition to sustainable and clean energy sources is urgently needed [2]. Solar energy, as an emerging green renewable resource, displays substantial potential for tackling these challenges. In recent years, the utilization of solar energy has continuously attracted the attention of chemists; it is usually converted into storable chemical energy or applied to trigger unfeasible chemical reactions. To effectively realize these conversion processes, the design and fabrication of appropriate catalysts are crucial. A collection of photo(electro)-catalysts has been successively developed, which exhibit good light response and reasonable energy bands, including metal oxides (e.g., TiO2, α-Fe2O3, WO3), metal sulfides and selenides (e.g., CdS, MoS2, CdSe), bismuth-based compounds (e.g., BiVO4, Bi2WO6), and organic polymer semiconductors (e.g., g-C3N4, COFs, MOFs) [3,4,5]. Of these, WO3 serves as a pivotal bridge linking conventional metal oxides and advanced materials with the merits of high chemical stability and adjustable electronic structures for further functionalization [6]. On the basis of existing industrial foundations and their ability to overcome the limitation of low visible-light utilization via engineering modification, WO3-based materials have great potential as a class of cornerstone catalysts within green chemical transformation (Figure 1).

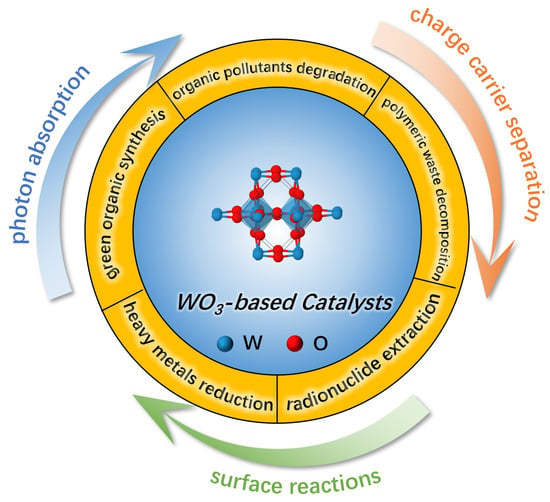

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of chemical conversion applications and key factors for WO3-based photo(electro)-catalysis.

As a representative n-type semiconductor, WO3 is regarded as a promising candidate for heterogeneous photo(electro)-catalysis systems owing to its outstanding advantages, such as low cost, easy preparation, strong corrosion resistance, good visible-light response, and narrow bandgap (2.5–2.8 eV). Benefiting from its unique intrinsic properties, the absorption edge of WO3 is extended to around 500 nm and can absorb approximately 12% of solar energy, and it possesses the remarkable electron mobility (10–12 cm2·V−1·s−1), facilitating the utilization of photoinduced charge carriers. Previous reports have proven that WO3 boasts a robust oxidation capacity and chemical stability under acidic or basic conditions (pH 2–7) [7,8]. However, single WO3 suffers from several inherent deficiencies, like poor harvesting of long-wavelength light, high charge transfer resistance, large hole diffusion length (~150 nm), severe carrier recombination, and sluggish surface-reaction kinetics, consequently restraining redox efficiencies. To overcome these limitations, researchers have been devoted to exploring novel modification strategies for intrinsic WO3 semiconductors so as to improve their catalytic performance. Multiple efficient approaches have been collectively developed to modulate their energy level structure and alter surface properties, including heterojunction construction, element doping, vacancy engineering, etc. [9,10].

2. Reaction Mechanisms, Influencing Factors, and Functionalization of WO3-Based Photo(electro)-Catalysts

2.1. Fundamental Reaction Mechanism of WO3 Photo(electro)-Catalysis

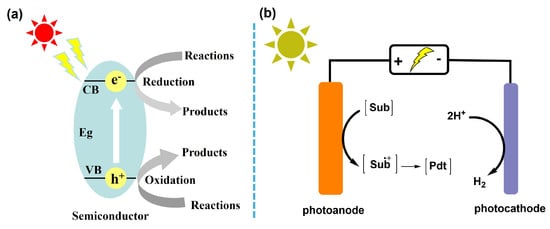

Generally speaking, heterogeneous photocatalysis (PC) mainly involves three key steps [11], namely photon harvesting, charge separation and migration, and surface reactions, as depicted in Figure 2a. Firstly, photocatalysts should absorb light irradiation, whose energy must be greater than or equal to the bandgaps of semiconductors, and thus photocatalysts are excited to yield photoinduced electron–hole (e-h+) pairs. Then, photoelectrons transition from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), while h+ remains on the VB of semiconductors, resulting in efficient separation and further transfer from the bulk to the catalyst surface. Meanwhile, reactants diffuse from a solution to catalysts and adsorb onto the surface, and are reduced by e− or oxidized by h+ to form target products and active species. Eventually, the formed substrates are desorbed from the catalyst surface and diffuse into the bulk solution with re-exposure of active centers. As for advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), reactive species are generated from the reduction of electron donors (e.g., O2, PMS, and H2O2), which oxidize and mineralize organic pollutants into CO2. Simultaneously, h+ with strong oxidizing abilities can directly decompose contaminant molecules. Any step during the photocatalysis process that is too slow will become the rate-determining step [12]. To optimize the reaction process, in 2020, König et al. [13] explored a synergistic catalytic system combining mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (mpg-CN) with a nickel-based cocatalyst to effectively yield active species under visible-light irradiation. Through a photogenerated hole-triggered single-electron-transfer route, the C(sp2)-C(sp3) cross-coupling reaction was efficiently achieved.

Figure 2.

(a) Mechanism of heterogeneous photocatalysis. (b) Mechanism of heterogeneous photoelectrocatalysis.

Analogous to the traditional PC process, photoelectrocatalysis (PEC) is also based on band structure theory and requires semiconductors as electrode materials. PEC systems represent a more intricate coupling of electrochemical and photochemical processes, centering on the introduction of an external circuit and an applied bias. In general, a three-electrode system, including working, counter, and reference electrodes, is required, which continuously works with the application of external voltage and light irradiation (Figure 2b). Powder photocatalysts are immobilized as a thin film on transparent single-side-conductive glass, like fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO), indium tin oxide (ITO), and aluminum-doped zinc oxide (AZO), to serve as the working photoelectrode. This system physically separates the catalyst from the reaction medium for better recycling utilization of the target catalyst, and easily realizes the precise control of reaction pathways. Noticeably, as an advantage over PC, an external bias can induce directional band bending at the semiconductor/electrolyte interface and create a powerful driving force for charge migration, which results in effective charge carrier separation for further redox reactions. Concurrently, the controllability and selectivity of conversion processes are also enhanced in suitable PEC systems [13,14,15,16]. For example, Liu et al. [17] anchored WO3 nanosheets onto vertically aligned TiO2 nanorod arrays via a two-step hydrolysis route to construct a heterojunction catalyst for photoelectro-oxidation of glycerol. The WO3/TiO2 interface efficiently boosted the separation of photogenerated charges and achieved efficient conversion of glycerol with high selectivity under illumination. Also, Wu et al. [18] employed an m-BiVO4 photoanode to build a self-biased system for C-H activation/cyclization with low energy cost and high selectivity. Driven solely by visible light, the overpotential was lowered and over-oxidation was prevented, enabling efficient and atom-economical reactions. This further underscores the unique advantages and potential of PEC technology for redox conversion reactions. In summary, the electrode material itself governs the intrinsic activity for light absorption, charge separation, and surface reaction. Concurrently, external operating parameters, such as applied potential, light intensity, and the distance between the electrode and light source, jointly modulate the driving force for charge separation and reaction kinetics. The synergistic interplay of these factors ultimately dictates the overall energy consumption and reaction efficiency of the system [19].

2.2. Influencing Factors for Photo(electro)-Catalysis Performance of WO3-Based Catalysts

2.2.1. Photon-Harvesting Capacity

Photon harvesting is fundamental to photo(electro)-catalytic systems. As mentioned above, the number of photoinduced charge carriers directly relies on the capacity of light absorption, which eventually triggers redox conversion and affects catalytic efficiency on the basis of the Grotthuss–Draper law [20]. Moreover, light absorption ability is mostly dependent on the bandgap of the semiconductor catalyst and thus influences the formation of photoinduced charge carriers [21,22]. For example, pure TiO2 can only absorb high-energy ultraviolet light, whereas the effective regulation of its bandgap extends the light absorption range to visible and near-infrared light, which can be achieved using S-TiO2−x, black TiO2, Er-Yb-co-doped TiO2, Yb3+/Tm3+ co-doping TiO2, and so on [23,24,25,26]. These modified TiO2 materials exhibit near-infrared-light-responsive capability, thus enabling them to efficiently absorb infrared light and realize the corresponding catalytic reactions [23,24,25,26]. Stronger light absorption commonly leads to an increasing amount of photogenerated charge carriers, thereby promoting catalytic activity [27]. As previously reported, Lee et al. [28] successfully utilized NiMoO4 (NMO) and BiVO4 to modify Sn-doped WO3 (Sn:WO3) by fabricating a novel NMO/BVO/Sn:WO3 double-heterojunction photoanode via a combined hydrothermal and spin-coating method. The process resulted in a thin-film-coated, vertically aligned nanosheet morphology. This structure significantly enhanced the material’s light absorption properties and greatly improved its photoelectrochemical (PEC) water-splitting performance. Zhou et al. [29] have successfully synthesized C-doped, oxygen-vacant WO3/Cu3SnS4 S-scheme heterojunction materials. Non-metal doping induced surface defects in the WO3/Cu3SnS4 heterostructure, which enhanced light absorption and facilitated dopant diffusion from the surface to the lattice. These modifications improved charge transfer and boosted photocatalytic performance. This work offers new strategies for designing photocatalytic systems and shows great potential for environmental and energy applications.

2.2.2. Charge Carrier Transfer and Separation Efficiency

The transfer and separation efficiency of photogenerated charge carriers directly impact the PC and PEC performances. Inefficient separation of charge carriers often leads to rapid recombination, with reduced carrier utilization and catalytic activity, resulting in heat release and fluorescence radiation [30]. The structure and composition of materials directly influence the behaviors of charge carriers, which in turn affect the catalyst lifespan and stability [31]. Efficient carrier separation significantly enhances catalytic efficiency, prolongs the lifetime of photoinduced charge carriers and reduces energy loss. For example, Li et al. [32] successfully fabricated an Auδ+-Ov-W5+ interfacial space charge layer in Au-WO3−x/TiO2. After introducing oxygen vacancies (Ov), the carrier separation efficiency was enhanced, thus improving the catalytic activity of the targeted material in photocatalytic oxidation of methane (POM). In addition, Wu et al. [33] and co-workers loaded Ov-modified WO3 nanosheets onto Ti3C2 MXene via a simple precipitation method, which was assessed by degradation of trimethylamine (TMA) under visible-light irradiation. Obviously, the adsorption of TMA on WO3 was enhanced with the Ov engineered, deriving from the strong nucleophilicity of N atoms in TMA to Ov. The construction of a 2D-2D structure led to a pronounced increase in photogenerated carrier concentration at the interface, and the formation of a Schottky heterojunction controlled the dynamic migration of charge carriers in composites. Consequently, the lifetime of the photogenerated carriers increased nearly fivefold with h+ in a dominant role, thereby improving the photocatalytic performance [34].

2.2.3. Surface Adsorption/Desorption and Photocarrier Utilization

Surface adsorption/desorption is the initial and crucial step during catalytic reactions. In most cases, reactant substrates need to adsorb on the catalyst surface and react with e− or h+. Correspondingly, the products and intermediates are desorbed into bulk solution to release active sites for continuous reactions [35]. The surface properties, such as chemical composition, crystallographic orientation, electronic structure, specific surface area, and surface charge, greatly affect reactant adsorption and molecular desorption. During reactions, surface adsorption/desorption indirectly influences carrier separation and transfer [36]. That is, the adsorbed molecules on the catalyst surface can trap electrons or holes to trigger redox reductions, thus promoting photocarrier utilization and reducing the recombination probability. As for PC and PEC, the recombination of photogenerated e− and h+ is unavoidable, causing the loss of catalytic ability [37]. Thereby, enhancing carrier utilization efficiency is pivotal for boosting photo(electro)-catalytic behaviors. Key strategies include the improvement of light absorption properties and optimization of the catalyst structure to increase the density of photogenerated charge carriers. Additionally, promoting carrier separation to increase their utilization can further elevate photocatalytic efficiency [38,39]. The improvement of PC and PEC activities hinges on maximizing the utilization of charge carriers, which is affected by enhanced light harvesting, engineered structures with high carrier density, and effective inhibition of carrier recombination. Strong surface adsorption synergistically amplifies this by supplying active sites that trap carriers and accelerate surface reactions; co-optimizing surface and bulk properties simultaneously advances both adsorption and utilization for high-efficiency catalysis [40,41,42].

For example, Wu and co-workers [43] successfully synthesized WO3-U through a direct annealing route with the addition of urea, which was a methodology conducive to large-scale production. Characterization results verified the presence of abundant oxygen vacancies in WO3-U. These oxygen vacancies played a pivotal role in facilitating photogenerated charge separation and activating H2O/O2 to form active species, thereby improving the utilization of photogenerated charge carriers for better oxidation activity. As a result, 50 mg/L of acetaldehyde was completely removed by WO3-U within 20 min, whose degradation efficiency was almost three times that of pristine WO3. Tang et al. [44] designed and fabricated photocatalysts using first-principles calculations as a comprehensive guiding tool. By precisely controlling the O2 activation process on noble-metal cocatalysts and adsorption strength of carbon-containing intermediates on metal-oxide supports, the selectivity of methane photooxidation products was precisely tuned. The bifunctional catalyst, featuring Pd nanoparticles and monoclinic WO3 (Pd/WO3), showed optimal O2 activation kinetics and moderate oxidation/desorption barriers, thus promoting HCOOH formation.

2.3. Synthesis and Modification Strategies for WO3-Based Materials

2.3.1. Synthesis Approaches for WO3-Based Materials

The catalytic performance of WO3 closely relies on its microstructure and surface properties, which are directly dictated by the synthetic route, including hydrothermal synthesis, sol–gel process, precipitation, electrodeposition, and so on. As a conventional synthesis approach, the hydrothermal process requires tungstate salts as precursors, which undergo dissolution, nucleation and growth to yield well-crystallized WO3 materials in a sealed autoclave at 120–200 °C and high autogenous pressure [45]. By controlling reaction temperature, reaction time, pH and surfactants, the unique morphologies (e.g., nanosheets, nanowires, nanorods or 3D hierarchical architectures) are precisely regulated. During preparation, the elevated temperature and pressure promote the formation of high crystallinity and surface defects, which facilitate photogenerated charge carrier transfer, and in situ doping is easily induced by the co-dissolution of external dopants. As for the sol–gel route [46], metal alkoxides or inorganic salts are first hydrolyzed and condensed to form a uniform sol solution, which is subsequently polymerized into a gel. Through dehydration and calcination, the target WO3 powders or films with high purity and atomic-scale homogeneity are easily obtained, which contributes to subsequent modification via element doping and heterostructure construction. In addition, uniform films can also be achieved by the deposition of WO3 powders onto substrates by spin- or dip-coating. However, alkoxide precursors are expensive and moisture-sensitive, and meanwhile, the gel phase undergoes considerable shrinkage to a reduced surface area during drying or annealing processes, directly affecting the final crystallinity. Especially for photocatalysis, the sol–gel route is favorable for preparing porous WO3-based catalysts with high specific surface area, whose abundant porosity supplies rich active sites for reactants, resulting in an improvement in catalytic activity.

Apart from these, precipitation is another effective route to obtain WO3-based catalysts. During synthesis, precipitation agents are first mixed into tungstate solution, and amorphous tungstic acid is yielded [47]. By high-temperature heat treatment, amorphous tungstic acid is easily transformed into WO3 with good crystallinity, and its particle size can be tuned to some extent by varying pH, concentration and stirring rate during precipitation. This synthesis procedure is simple, inexpensive and easily scaled from bench to plant. Yet, the product catalyst often suffers from irregular morphologies, uneven size distributions and severe agglomeration with loss of specific surface area. The lack of morphological control and surface area of WO3-based catalysts derived from precipitation usually cause a decrease in active sites and an increase in inter-particle resistance, hindering photogenerated charge transport and separation during photo(electro)-catalysis processes. Furthermore, electrochemical deposition [48] has been developed to prepare well-distributed WO3 with an electrolyte containing a tungsten source (e.g., [WO4]2−). By applying a suitable cathodic potential, a change in local pH is induced and triggers the formation of WO3 precipitation on conductive substrates, which is converted into well-crystallized WO3 after mild annealing. High-quality thin films are easily grown on conductive substrates via electrochemical deposition, making them exceptionally well-suited for photo(electro)-catalysis. Notably, the thickness, morphologies, and crystal phase of the WO3 film can be finely adjusted by varying the deposition potential, current density, electrolyte composition, and reaction temperature. Moreover, the process enables uniform coating over large areas or substrates with complex geometries. However, conductive substrates are needed for the growth of WO3 materials, and powder catalysts are difficult to obtain for PC reactions. From another perspective, electrochemical deposition is a promising candidate for fabricating WO3 photoelectrodes, in which vertically aligned nano-arrays are in situ-grown with the enlargement of the reactive surface and then provide directional pathways for photogenerated carriers, remarkably improving charge transfer and utilization for overall photo(electro)-catalytic activity. Among various synthesis techniques for WO3, the precipitation method is widely employed to prepare oxide nano-films with controllable nanostructures and tunable physical properties. Recognized as an environmentally friendly and cost-effective approach, it typically yields WO3-based photocatalysts with high particle purity, good dispersion, and high crystallinity. In contrast, other methods such as hydrothermal and calcination often lead to an orthorhombic structure that compromises the stability of the WO3 nanostructure. Moreover, the hydrothermal method is time-consuming and less suitable for large-scale production. As shown in Table 1, we systematically summarize the advantages and limitations of various synthesis methods.

Table 1.

Summary of preparation methods for WO3-based photo(electro)-catalysts.

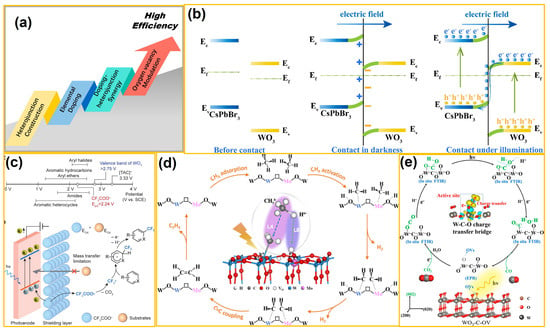

2.3.2. Heterojunction Construction

To improve the PC and PEC activity of WO3-based catalysts, various modification strategies have been developed. As shown in Figure 3a, common modification methods include heterojunction construction, element doping, vacancy engineering, etc. Typically, heterojunction photo(electro)-catalysts are constructed by coupling two semiconductor catalysts. Thermodynamically, the driving force of PC and PEC comes from the potential difference between the CB and VB and redox potentials of reactants. To achieve strong solar light harvesting, narrow bandgaps with suitable CB and VB positions are required. To realize this purpose, the construction of heterostructures is superior to photo(electro)-catalysts and is gradually becoming a key research hotspot for heterogeneous photo(electro)-catalysis [49]. For instance, Lee et al. [50] have introduced a novel CAU-17, originating from BiVO4 nano leaves synthesized on WO3 layers through hydrothermal reactions, which is simple, uniform, stable, scalable, and cost-effective. These MOF-derived ternary oxides, inheriting the features of MOFs with unique morphology and uniform cation composition, shed new light on designing high-performance photoanodes. In addition, as shown in Figure 3b, Shi et al. [51] prepared an S-scheme WO3/CsPbBr3 heterostructure using melamine foam as a support through the electrostatic self-assembly route. The suitable energy level alignment between CsPbBr3 and WO3 facilitates charge carrier migration in the system via an S-scheme path. Under sunlight irradiation, the optimal WO3/CsPbBr3 photocatalyst exhibited a remarkably enhanced CO2 reduction performance in aqueous solution, and high stability was also proved by cycling tests.

Figure 3.

(a) Common methods for modifying WO3. (b) Before contact, contact in darkness, and contact under illumination and corresponding S-scheme charge transfer route in heterojunction (from ref. [51], with permission). (c) Ion shield–hPEC strategy for prioritizing electron transfer from CF3COO− anions in the presence of easier-to-oxidize substrates (from ref. [52], with permission). (d) Schematic illustration of photocatalytic nonoxidative conversion of CH4 to C2H4 over Mo-WO3−x (from ref. [53], with permission). (e) C-doping induces oxygen vacancies in WO3 nanosheets for CO2 activation and photoreduction (from ref. [54], with permission).

2.3.3. Element Doping

Element doping is a highly effective approach to regulate the electronic energy level structure of WO3 to enhance its light response and optoelectronic properties. By altering different dopants, the bandgap of WO3 is rationally narrowed or widened with an increase in carrier density and appropriate band edge positions [55]. Isovalent dopants avoid charge mismatch after doping modification, whereas non-isovalent ones usually compensate for electrical neutrality by creating or increasing oxygen vacancies. Hence, the effects of metal and non-metal element doping on the photo(electro)-catalytic performances of WO3 have been investigated in depth and turned into a critical research focus [56]. For example, as displayed in Figure 3c, Mo and co-workers [52] developed an ion-shielding-selective oxidative decarboxylative trifluoromethylation method using 1% Mo-doped WO3 as the photoelectrocatalyst. This innovative result addressed the challenge of selectively oxidizing inert substances within a single system. By employing trifluoroacetate as the trifluoromethyl source, the trifluoromethylation of substrates was realized at a low oxidation potential. This work also broadened the application of photoelectrocatalytic technology in green organic synthesis. Moreover, as shown in Figure 3d, Xue et al. [53] designed and synthesized a Mo-WO3−x photocatalyst by isotypically substituting W atoms with Mo6+ ions. The unsaturated Mo sites and frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs) were synchronously introduced onto the surface of a composite. Characterization analysis revealed that the formation energy of oxygen vacancies was lowered after Mo doping, which was precisely positioned between Mo and W atoms, thereby facilitating the formation of FLPs. These obtained FLPs, composed of unsaturated W atoms and lattice O atoms, effectively activated CH4 and promoted C-H bond cleavage.

In addition, the synergy effects of element doping and heterojunctions have also been employed to alter the surface charge and enhance adsorption of target molecules on catalyst surfaces [57]. For example, an effective BiVO4/P-g-C3N4 heterojunction with its modified surface charge was fabricated by Li et al., which exhibited improved adsorption and catalytic oxidation of anionic dyes due to plentiful positively charged sites. Clearly, element doping introduces additional active centers, while heterojunction construction favorably optimizes charge distribution for better catalytic activity [58]. Furthermore, a Zn-doped SnO2/ZnO heterojunction not only increased the number of active sites but also boosted their catalytic activity through interfacial heterojunction interactions. Similarly, Lin and colleagues [59] fabricated Pt WO3@W/GNs composites, which featured a core–shell structure with intimate ohmic contact, using a facile solid-phase method. These composites exhibited exceptional bifunctional electrocatalytic performance for methanol oxidation reactions (MORs) and oxygen reduction reactions (ORRs) in acidic conditions. Upon being irradiated, a significant enhancement was observed in the catalytic activity for both the MOR and organic conversion. In addition, Li and co-workers [60] successfully constructed Co-doped WO3/TiO2 nanorod arrays to enhance PEC performance. Benefiting from Co doping, the band structure of a WO3 shell was rationally adjusted, eventually improving charge separation between the WO3 shell and TiO2 core. Specifically, Co doping increased W5+ ions and oxygen-vacancy defects in the WO3 lattice, which also facilitated water-splitting reactions. Also, Yan et al. [61] designed and prepared porous Mo-doped WO3@CdS hollow microspheres with unique hierarchical heterostructures. The obtained catalysts effectively reduced gaseous N2 to NH3 under mild conditions. The Mo doping and interconnected porous heterostructure acted jointly to provide enough active sites for catalytic conversion, making PEC reduction of N2 more efficient.

2.3.4. Vacancy Engineering

Introducing oxygen vacancies can also precisely modulate the electronic structure and adjust the electron distribution of metal oxides. This functionalization modification narrows the bandgap of the semiconductor, enhances light absorption, alters the oxidation state of metal sites, and promotes electron transfer [62]. Additionally, oxygen vacancies supply active sites that lower activation energy and thus boost chemical reaction rates [63]. For example, Wang et al. [64] doped Mo into a WO3 lattice, reducing the energy barrier for oxygen-vacancy (Ov) formation. This strategy dynamically allowed in situ generation of more photoinduced oxygen vacancies on the surface during photocatalysis. Most importantly, the dynamic formation and stability of oxygen vacancies were ensured under light irradiation, and the deactivation issue of traditional Ov photocatalysts was addressed. And then, a photochemical method was also used by Wang et al. to create rich OV sites on WO3. The introduced Ov sites could activate O2 and were aligned with photogenerated carrier dynamics, thus boosting photocatalytic benzene’s oxidation to phenol. Under visible-light illumination, photoinduced OV sites prevented irreversible WO3 structural changes and over-reduction of metals, retaining the inherent photocatalytic traits of WO3-based materials. Furthermore, as displayed in Figure 3e, Dong and colleagues [54] demonstrated a simple and controllable strategy to prepare WO3 nanosheets by surface structure reconstruction process. Using 2D WO3 nanosheets as a template, surface carbon doping induced the formation of Ov and created abundant unsaturated sites via C-Ov coordination. With W-O-C covalent bonds as bridges, photogenerated charge carriers were easily transferred to surface-adsorbed species. Also, CO2 chemisorption was enhanced owing to C-Ov coordination, and the activation energy barrier of CO2 was lowered on WO3 atomic layers, greatly improving CO2 photoreduction activity and selectivity.

3. Applications of WO3-Based Materials in Green Photo(electro)-Catalysis

3.1. Photo(electro)-Catalytic Degradation for Organic Pollutants

A wide range of persistent organic pollutants (POPs), including pesticides, industrial chemicals, petroleum hydrocarbons, and fire retardants, present serious environmental challenges and must urgently be eliminated from environmental media [65]. These toxic compounds are inevitably discharged into natural water bodies along with industrial production, posing serious threats to ecological environmental security and human health. To effectively address these concerns, a comprehensive approach involving source control, stringent regulation, and the application of advanced technologies is essential [66]. Conventional terminal-managed methods (e.g., adsorption, flocculation, activated sludge, and membrane separation), though important, are constrained by inefficiency, high costs, and secondary pollution. Advanced oxidation processes, like heterogeneous PC and PEC techniques, directly improve biodegradability of POPs or mineralize residual COD, which have become a research hotspot as environmentally friendly and highly efficient routes. Integrating emerging technologies for cleaner degradation processes is vital, and in this context, WO3 stands out as a promising green catalyst [67]. Table 2 systematically summarizes and compares a series of WO3-based materials on photo(electro)-catalytic degradation of organic pollutants, offering valuable insights for the rational optimization of catalysts and reaction conditions.

Table 2.

Summary of WO3-based catalysts for PC or PEC degradation of organic pollutants.

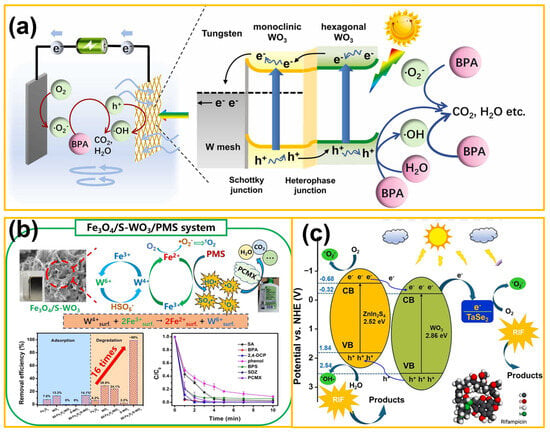

For instance, Wang et al. [68] fabricated a novel double-Z-scheme g-C3N4/WO3/AgI photocatalyst by combining electrostatic self-assembly and selective deposition routes. Compared with a single component, the photodegradation activity of neonicotinoid (NTP) over the composite was significantly enhanced upon illumination by visible light. Through various characterizations and theory calculations, possible reasons were proved to be the boosted charge transfer and separation efficiency after constructing a double-Z-scheme structure, which also resulted in high reduction and oxidation capabilities for photogenerated electrons and holes, respectively. Moreover, Guo et al. [69] successfully designed and prepared WO3/UiO-66 nanocomposites via a microwave hydrothermal approach, and used the target photocatalyst to degrade rhodamine B (RhB) under visible-light irradiation. By characterization tests, the optimized WO3/UiO-66 nanocomposite featured an SBET of 200.62 m2/g and a bandgap of 3.89 eV. Among all samples, the WO3/UiO-66–5 exhibited exceptional photocatalytic performance under simulated sunlight irradiation, and the degradation rate of RhB achieved 96.6% within 100 min, surpassing the individual WO3 and UiO-66. Apart from these, as given in Figure 4a, Li and co-workers [70] prepared an hm-m-WO3/W photocathode with a unique network structure via an in situ growth method, and used it for PEC degradation of bisphenol A (BPA). Superior degradation efficiency (~100%) was obtained for BPA with a TOC removal rate up to 84.5% under a bias of 1.2 V (vs. RHE). To improve PMS activation, as shown in Figure 4b, Zhou et al. [71] decorated S-WO3 onto Fe3O4 by forming an S-WO3/Fe3O4 heterostructure through a hydrothermal route, and utilized the composites as outstanding PMS activators for POP degradation. In comparison with Fe3O4, the incorporation of S-WO3 greatly enhanced the activation of PMS and catalytic activity. As a result, the degradation rate for RIF over S-WO3/Fe3O4 increased up to 0.3506 mmol·g−1·min−1, which was 4 and 4.5 times higher than single Fe3O4 and S-WO3, respectively. Also, a broad degradation spectrum of pollutants was obtained for target S-WO3/Fe3O4, including methylene blue, rhodamine B, phenol, 2,4-dichlorophenol, and tetracycline. In 2025, as displayed in Figure 4c, Joo et al. [72] fabricated TaSe2/WO3/ZnIn2S4 nanocomposites by a facile 3D-printed method with sodium tungstate, InCl3·4H2O, and ZnCl2 as original materials. These composites exhibited enhanced light absorption, improved charge carrier separation, and efficient charge transfer. Electron spin resonance (ESR) tests were also conducted using DMPO as a radical trapping agent to further investigate radical generation in the TaSe2/WO3/ZnIn2S4 photocatalytic system; the main reactive oxygen species were confirmed to be O2/•O2−, which were responsible for rifampicin antibiotic degradation. The material demonstrated structural stability and high degradation efficiency across various water environments, emphasizing its durability and adaptability for sustainable wastewater treatment.

Figure 4.

(a) Schematic mechanism of PEC degradation performance by hm-m-WO3/W mesh (from ref. [70], with permission). (b) Enhanced activation of PMS by a novel Fenton-like composite Fe3O4/S-WO3 for rapid chloroxylenol degradation (from ref. [71], with permission). (c) Photocatalytic mechanism proposed for TaSe2/WO3/ZnIn2S4 nanocomposites (from ref. [72], with permission).

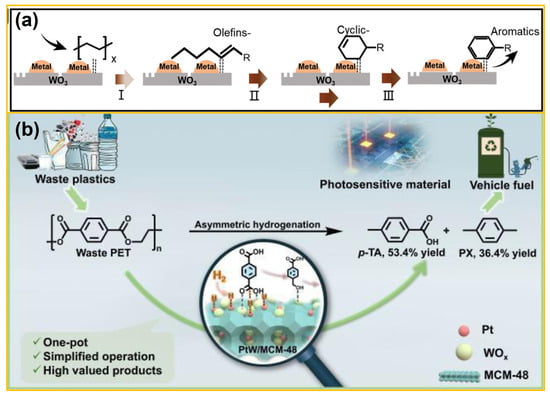

In recent years, plastic products have been regarded as one of the most important carbon resources worldwide, similar to fossil fuels, biomass, and CO2 [73]. Differing from POPs, plastic waste has emerged as a class of polymeric organic pollutants in natural environments, especially in water bodies, and has gained increasing attention over the past decades. Traditional disposal methods, like mechanical processing and incineration, are material-intensive and mainly produce low-value outputs [74]. Transforming polymeric waste into high-value-added compounds opens up the prospect of research on treatment and resource utilization of plastic waste, for which heterogeneous photo(electro)-catalysis techniques provide potential feasibility. A key priority in this special issue is the development of green and efficient catalysts. Considering the low cost and favorable physicochemical properties, WO3 is rapidly establishing itself as a highly promising candidate [75]. In 2023, Liu et al. [76] anchored noble metal Pt on defective 2D WO3 nanosheets through a space limitation strategy, and the optimal load amount of Pt was determined to be 0.2 wt.%. Obviously, high-density polyethylene (HDPE) waste decomposed at 200–250 °C, achieving a liquid fuel (C5–C18) production rate of 1456 gproduct · gmetal species−1·h−1. The mechanism analysis revealed that HDPE chains were adsorbed around 2D defective WO3, while the strong interactions between Pt and monolayer WO3 accelerated the cracking of HDPE, offering insights for future catalyst design for upcycling of polymer wastes. Subsequently, as shown in Figure 5a, Wang et al. [77] further utilized transition metals (e.g., Fe, Co, and Ni) to substitute expensive Pt noble metal, which was decorated on the surface of 2D WO3 nanosheets as cocatalysts for HDPE conversion. It could be observed that HDPE macromolecules were easily converted into alkanes and alkenes at low temperatures and ambient pressure. Notably, the usage of hydrogen (H2) was avoided, thus reducing the production costs and security risks. By comparison, 2D Ni/WO3 exhibited the best catalytic behavior due to the abundant surface acid sites, benefiting the triggering of HDPE cracking at 240 °C. In addition, as displayed in Figure 5b, Mei and co-workers [78] designed and engineered a highly efficient bifunctional catalyst, namely a PtW/MCM-48 composite, for selective hydrogenation of PET waste into high-value-added p-toluene (p-TA) and para-xylene (PX). Under the optimal conditions at pH = 2 and H2 pressure of 2 MPa, the desired PtW1.5/MCM-48 catalyst achieved complete PET conversion with a remarkable p-TA yield of 53.4% and a PX yield of 36.4%. Noticeably, the catalyst displayed robust performance in processing real PET waste, including colored and commingled plastic fibers, implying the potential of WO3-based materials in controlling and upgrading polymer organic wastes.

Figure 5.

(a) Proposed reaction pathways of catalytic cracking over Fe/WO3 (from ref. [77], with permission). (b) Selective asymmetric hydrogenation of waste polyethylene terephthalate via controlled sorption through precisely tuned moderate acid sites (from ref. [78], with permission).

3.2. Applications in Organic Synthesis

Under the green chemistry concept, organic synthesis researchers focus on creating green, efficient, simple, low-cost, and high-chemical-selectivity methods. Heterogeneous semiconductors, which can capture photons, cause charge separation, and are easy to recover and synthesize, have drawn attention from organic chemists [79]. Their use in organic synthesis and transformation offers greener pathways. WO3 is a standout material in organic synthesis, particularly excelling in photo(electro)-catalysis and acid catalysis. It stands out for its multi-electron-transfer capability, adjustable valence states, visible-light responsiveness, and surface acidity, making it a standout green and efficient tool for synthesis [80]. As reported by Zhang et al., the effective oxidation of olefins over WO3 in the presence of peracetic acid was early discovered by Mugdan and Clark in 1949 [81]. This pioneering work unveiled the bifunctional acid catalysis mechanism of WO3 (synergistic Brønsted and Lewis acidity), established a foundation for designing heterogeneous WO3 catalysts, and set the stage for its photocatalytic and electrocatalytic applications in organic synthesis that emerged six decades later [81,82]. In recent years, there has been a surge in scientific interest in utilizing WO3 for organic synthesis. For example, He et al. [83] have developed a semi-heterogeneous photocatalytic strategy for the oxidative hydroxylation of alkyl and aryl boronic acids. By using cost-effective and commercially available WO3 as the photocatalyst, Triphenylamine (NPh3) as a single-electron donor, air as both a single-electron acceptor and oxygen source, and DMF as the solvent and hydrogen source, various hydroxylated compounds with excellent functional-group compatibility can be achieved in high yields. Moreover, the synergistic effect of air and NPh3 could significantly inhibit charge carrier recombination in WO3. Research has predominantly concentrated on employing PC or PEC conditions to oxidation reactions, reduction reactions, and other reactions in organic molecules, thereby enabling a variety of subsequent reactions.

3.2.1. Oxidation Reactions

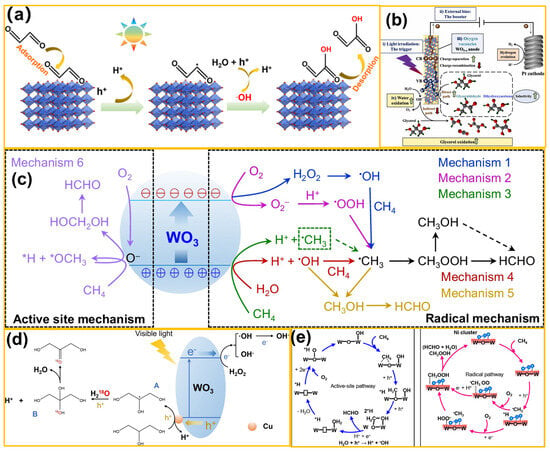

At the onset of photo(electro)-catalysis, when the energy of absorbed photons is equal to or exceeds the bandgap of the semiconductor catalyst, electrons of the semiconductor catalyst are excited from the VB to the CB, leaving behind holes in the VB [84]. During photo(electro)-catalysis, excited charge carriers can be captured within picoseconds (ps), while the recombination of holes and electrons occurs within tens of nanoseconds. The interface and surface properties significantly influence reaction mechanisms and timescales of photoinduced charge transfer [85]. So, interface charge transfer is critical for redox reactions, which could directly oxidize or reduce organic molecules and generate reactive species (e.g., hydroxyl and superoxide radicals). For example, Zhao et al. [86] regulated the (200) facet of WO3 (Figure 6a) to achieve high-selectivity semi-oxidation of ethylene glycol. By combining batch experiments and theoretical calculations, it was found that the (200) facet of WO3 exhibited strong adsorption toward ethylene glycol and possessed low formation energy for the ethylene glycol radical. Similarly to the prior study, as shown in Figure 6b, Xiao et al. [87] successfully fabricated a WO3 nanosheet photoanode exposing the (002) facet, termed as (002)-W, through using a capping agent. By tailoring the crystal facet of WO3, it was found that the (002) facet possessed an abundance of surface states, which enhanced charge separation and prolonged carrier lifetimes. Using the PEC oxidation route, glycerol was efficiently converted into glyceric acid, offering a novel strategy for upgrading biodiesel byproducts. In 2024, Tang et al. [88] employed WO3 with {001} and {110} facets as a model photocatalyst (Figure 6c), and evaluated the catalytic activity of CH4 oxidation to HCHO as well as unveiled the reaction pathway in depth. The {001} facet endowed WO3 with nearly 100% HCHO selectivity through an active center mechanism. Conversely, the {110} facet, which relied on a radical pathway, could not ensure high HCHO selectivity. These findings provide valuable insights into the reaction mechanisms and offer guidance for designing high-performance photocatalysts for selective CH4 oxidation. In addition, Xiong and co-workers [89] developed a novel Pt-nanoparticle-modified WO3 photocatalyst. The Pt nanoparticles, acting as electron acceptors and cocatalysts, promoted photogenerated charge carrier separation and boosted O2 adsorption and dissociation, thus improving photocatalytic performance. The electronic structure of WO3 was also adjusted, thereby strengthening the adsorption of *CHxO intermediates on its surface. This led to excellent performance in directly converting CH4 to HCOOH. Tang et al. [90] designed a Cuδ+-modified WO3 photocatalyst to efficiently convert glycerol into valuable products like triesters (Figure 6d), glycerol aldehyde, and dihydroxyacetone with the assistance of visible light and H2O2. Subsequently, Tang et al. [91] pioneered the construction of an efficient dual-active-site photocatalytic system (Figure 6e). By synergizing non-noble-metal nickel (Ni) clusters with lattice oxygen in WO3, high yield, high selectivity, and stable oxidation activity of CH4 to HCHO were achieved. This achievement offered a low-cost and high-selectivity solution for CH4 conversion under mild conditions.

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic illustration of selective PEC oxidation of glyoxal to GA on a WO3 nanoplate photoanode (from ref. [86], with permission). (b) Mechanism of photo(electro)-catalytic glycerol valorization to high-value-added chemicals and simultaneous hydrogen production using a WO3 catalyst under mild conditions (from ref. [87], with permission). (c) Multiple reaction pathways of photocatalytic CH4 oxidation to HCHO (from ref. [88], with permission). (d) Proposed reaction mechanism of glycerol oxidation on Cu-modified WO3 (from ref. [90], with permission). (e) Schematic illustration of the proposed mechanism for CH4 oxidation to HCHO based on active sites (from ref. [90], with permission).

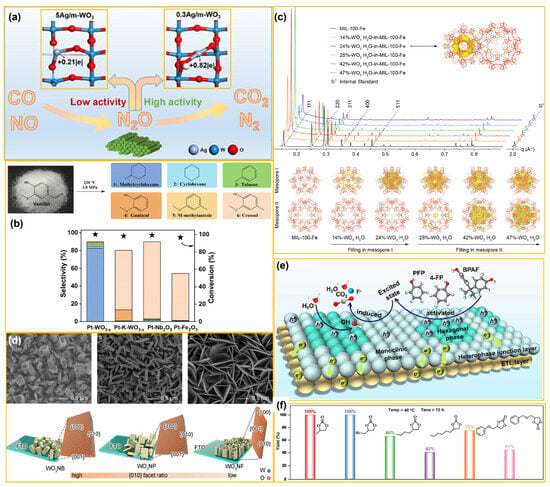

3.2.2. Reduction Conversion

Normally, the photo(electro)-catalytic reduction mechanism can be generalized into two key steps, i.e., surface adsorption/activation and reduction reaction. Firstly, organic substrates and reducing agents (e.g., hydrogen sources) must be adsorbed and activated on the catalyst surface. Active sites on the catalyst chemically bond with substrate molecules and thus lower the activation energy of target reactions. For example, in benzene hydroxylation via photocatalysis, benzene molecules are adsorbed onto the catalyst surface and react with photogenerated h+. Subsequently, photogenerated electrons drive reduction reactions, converting organic substrates into ideal products. As for PC or PEC water splitting, valence electrons directly reduce protons to generate H2 gas [92]. For example, Hou and co-workers [93] developed a Cu1/WO3 catalyst with single-atom Cu sites. The component WO3 dissociates water and supplies protons to the Cu1 sites. The electron-deficient Cu1 sites efficiently reduce NO3− to NH3. The desired catalyst achieved 99.2% ammonia selectivity and 93.7% Faraday efficiency, outperforming most reported catalysts. Furthermore, an integrated continuous-flow system combining a NO3RR electrolyzer with a vacuum-driven membrane separator was also designed for effective ammonia synthesis from nitrate-polluted water. Zhang and colleagues [94] constructed an S-scheme heterojunction of WO3/metal covalent organic frameworks (THFB-COF-M, M = Zn, Ni, Cu), which facilitated the efficient separation of photogenerated carriers. By refining carrier dynamics and reaction pathways, the unique structure advanced artificial photosynthesis technology and significantly enhanced the photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance, offering a viable material solution to help realize carbon neutrality. Su’s group [95] prepared a CO-SCR catalyst with high catalytic activity (Figure 7a) that worked well in O2-containing conditions. By tuning the amount of Ag precursor, the local Ag-O coordination environment was engineered, which promoted efficient and selective catalytic reduction of NOx by CO. Finally, a viable approach was offered to modulate the local environment of Ag single-atom catalysts with boosted CO-SCR performance. In addition, as displayed in Figure 7b, Kong et al. [96] reported a novel strategy to enhance the product selectivity of vanillin hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) by leveraging the synergy between Pt0 and oxygen vacancies. The Pt-WO3−x catalyst, synthesized via inert-gas calcination, exhibited high selectivity for methyl cyclohexane (MCH). This study demonstrated that Pt species and Ov sites on WO3−x are jointly responsible for hydrogen dissociation and enhancement of the catalytic activity for vanillin HDO, consequently achieving a toluene selectivity of 92.5% and conversion of 99.9%. In addition, the Pt-WO3−x catalyst exhibited a broad applicability in the hydrodeoxygenation of other lignin-derived phenols. As given in Figure 7c, Deng et al. [97] further employed a molecular compartment strategy in designing a visible-light-driven photocatalyst for full conversion of CO2. The WO3 and WO3·H2O nanoparticles were positioned in the mesopores of a metal–organic framework (MOF). This enabled the efficient overall conversion of CO2 and H2O into CO, CH4, and H2O2 under visible-light irradiation. The orderly arranged pores were neatly aligned with the narrow bandgap of semiconductor nanoparticles, consequently facilitating charge carrier separation and transfer as well as obtaining high CO2 conversion efficiency.

Figure 7.

(a) Tailoring the electronic structure of single Ag atoms in Ag/WO3 for efficient NO reduction by CO in the presence of O2 (from ref. [95], with permission). (b) Results of vanillin HDO over Pt catalysts with different supports (from ref. [96], with permission). (c) Location of WO3·H2O nanoparticles inside the mesopores of MOFs in the molecular compartments (from ref. [97], with permission). (d) SEM images and schematic illustration of monoclinic WO3 nanostructures with different {010} facet ratios on substrates (from ref. [98], with permission). (e) Schematic mechanism of PEC degradation of fluorinated compounds (from ref. [99], with permission). (f) CO2 cycloaddition of various epoxides using Ir1–WO3 reacting at 40 °C for 15 h (from ref. [100], with permission) over a double-WO3 photoelectrode.

3.2.3. Other Reactions

The realm of heterogeneous PC and PEC organic reactions is rapidly expanding beyond traditional redox processes. Through thoughtful catalyst design, leveraging photoinduced acid/base sites, energy transfer, surface adsorption/activation effects, radical chain reactions, and photothermal synergies, a broad range of organic transformations can be efficiently achieved [98], including acid- or base-catalyzed reactions, radical additions/polymerizations, cycloadditions, isomerizations, and photothermal catalysis. These non-redox pathways significantly enrich the potential applications of PC and PEC in green organic synthesis, material preparation, and the fine chemical industry [101].

As displayed in Figure 7d, Xiong and co-workers [102] have successfully realized the optimization of reaction activity by controlling hydroxyl radical (·OH) formation on WO3 through crystal facet engineering. This approach enabled efficient ethylene glycol production via a PEC CH4 conversion process. The findings indicated that surface-bound ·OH exhibited the highest reactivity on the {010} facet of WO3, providing valuable insights for the design of active and selective catalysts in PEC CH4 conversion. Li and co-workers [99] have designed and synthesized a stable Ir1-WO3 single-atom catalyst (Figure 7e), which was utilized for CO2 cycloaddition reactions between oxystyrene and styrene carbonate with high efficiency and stability. The Ir atoms were substituted for W atoms in the WO3 lattice to form well-dispersed single atoms. Compared to other oxide-supported Ir single atoms, this reported catalyst exhibited stronger electronic metal–support interactions (EMSIs), which enhanced CO2 cycloaddition activity and stability. As shown in Figure 7f, Li et al. [100] successfully fabricated a double-layer WO3 photoelectrode (termed double-WO3) on a tungsten mesh, integrating an electron transport layer (ETL) and a heterojunction. The built-in electric field of the outer layer enhanced charge separation, while the ETL in the inner layer accelerated electron extraction, effectively curbing electron–hole recombination. This innovative photoelectrode demonstrates exceptional efficiency in degrading fluorinated organic pollutants. In addition, Han et al. [103] developed an electrochemical approach for upgrading nitrate to hydrazine under ambient conditions. This process first electrochemically reduced nitrate to ammonia (NH3), which was then selectively coupled via ketone-mediated NH3 oxidation. Using diphenyl ketone (DPK) as a mediator, the WO3 catalyst achieved an overall selectivity of 88.7% for N2H4 production from NOx. Both the WO3 catalyst and DPK mediator showed remarkable reusability, highlighting their potential for green hydrazine synthesis.

3.3. Metal-Containing Wastewater Treatment

3.3.1. Reduction and Extraction of Radioactive Metallic Elements

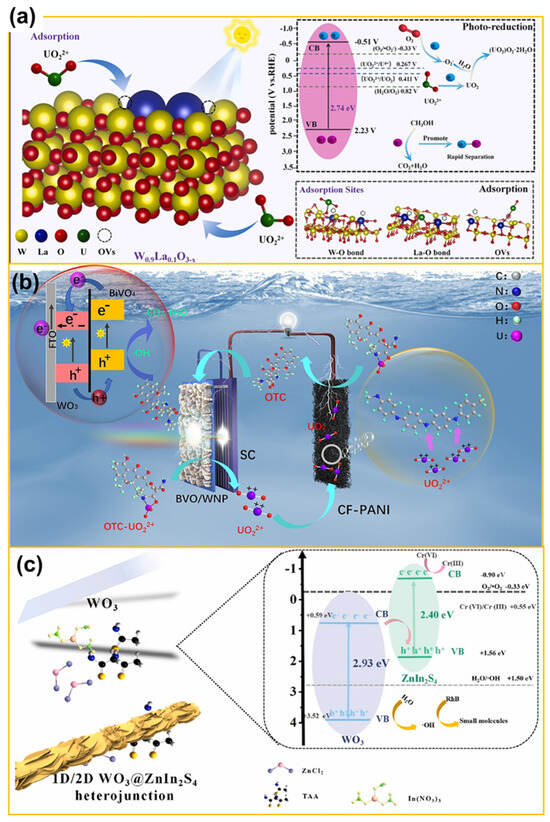

With the development of nuclear industries, vast quantities of radioactive wastewater containing soluble uranium are released into the environment from uranium mining, nuclear power plant operation, and potential nuclear accidents or conflicts. Given uranium’s intense radioactivity, prolonged half-life, and high toxicity, its extended mining inflicts severe harm on human health and ecosystems. Consequently, developing a low-cost method for uranium separation and extraction from mining wastewater is both urgent and significant. Conventional treatment methods for uranium-laden wastewater include adsorption, evaporation, membrane processes, and chemical precipitation [104]. Radioactive wastewater systems with uranium typically contain diverse soluble organics. Photocatalytic technology, capable of simultaneous organic degradation and U(VI) reduction, holds significant promise for application [105]. When semiconductor photocatalysts absorb light, photogenerated electrons can reduce soluble U(VI) to U(V) or insoluble U(IV), facilitating uranium reduction and immobilization [106]. On the other hand, U(VI) with high valence can be fixed and extracted from water bodies through direct reaction with reactive species, such as H2O2 and ·OH. For example, He et al. [107] proposed a novel method for treating uranium-containing wastewater by introducing oxygen vacancies into WO3 nanosheets. This extended the visible-light response range of WO3 and also enhanced U(VI) adsorption on WO3 nanosheets, thereby offering a successful example of improving U(VI) reduction via vacancy engineering in metal oxides to mitigate pollutants. Furthermore, as displayed in Figure 8a, Guo et al. [108] attained a performance breakthrough in WO3-based materials by cleverly coupling rare-earth doping with defect engineering. La incorporation not only formed a dynamic O-vacancy network but also activated the “self-evolution” ability of the photocatalyst. During photocatalysis, W6+ spontaneously reduces, continuously generating new active sites that enhance the material’s performance with each cycle. Similarly to the previous method, Sun et al. [109] used a simple solvothermal approach to synthesize oxygen-rich vanadium-doped tungsten oxide (WO3−x). The target sample showed high adsorption capacity and photocatalytic activity. Under simulated sunlight, it effectively removes U(VI) through initial adsorption and subsequent reduction. In addition, as given in Figure 8b, Wang and colleagues [110] developed a simple yet efficient PEC approach for effective U(VI) removal and recovery from wastewater. By introducing uranium substitution at iron sites in a hematite structure and utilizing it as a photoanode, the prepared uranium-doped hematite photoanode delivered a photocurrent of 51.21 mA/cm2 at 1.2 V (vs. SCE) and exhibited high stability during prolonged light exposure. Surprisingly, U(VI) was nearly completely removed from wastewater within 8 h (k = 0.182 h−1) and functioned effectively in complex matrices. Also, Zeng and co-workers [111] developed an SWRS system and used CF-PANI as the cathode and BVO/WNP-SC as the monolithic photoanode for uranyl extraction. Under sunlight illumination, the system efficiently recovered uranium, degraded organics, and generated electricity at the same time. Near-perfect removal rates of UO22+ and organic substances were achieved, thus providing valuable insights for designing high-activity cathode materials for uranium reduction. Furthermore, Wang et al. [112] prepared ZnS/WO3 composites via coprecipitation by forming a Z-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst. When applied to photoreduction of U(VI), the composite displayed a high charge separation efficiency and photoreduction activity was enhanced, achieving a U(VI) removal rate of 93.4%. In situ characterization tests and density functional theory calculations revealed that the desired composite provided an internal electric field that facilitated Z-scheme electron transfer, and a two-electron transfer pathway was discovered. To better compare and analyze the catalytic behaviors, a series of WO3-based materials for application in photo(electro)-catalytic reduction and extraction of toxic radionuclides and heavy metals were summarized and are given in Table 3, elucidating the underlying mechanisms and providing a theoretical basis for optimizing catalysts and reaction conditions.

3.3.2. Reduction of Heavy Metals

Heavy metal-containing wastewater is non-degradable, highly toxic, hard to metabolize, and often hidden, posing severe risks to ecological systems and human health. Current treatment methods like dilution, chemical precipitation, coagulation–flocculation, and adsorption have drawbacks such as high costs, incomplete treatment, and possible secondary pollution [113]. Photo(electro)-catalytic technology offers several key advantages for purifying metal-containing wastewater. Utilizing solar energy as the driving force, the stable metal complexes can be efficiently disrupted, allowing this technology to be used in the advanced treatment of low-concentration wastewater. The eco-friendly nature is highlighted by minimal sludge production and reduced chemical usage, and great potential has also been shown for selective reduction and recycling of valuable metals [114]. Despite challenges in catalyst performance and engineering applications, as a green and sustainable technology, it demonstrates unique competitiveness and broad prospects in treating hard-to-degrade organometallic compounds and recovering precious metals [115].

Table 3.

Summary and comparison of various WO3-based catalysts for efficient removal of toxic radionuclides and heavy metals by PC and PEC routes under different conditions.

Table 3.

Summary and comparison of various WO3-based catalysts for efficient removal of toxic radionuclides and heavy metals by PC and PEC routes under different conditions.

| Catalysts | Pollutant Type | Initial Concentration | Contact Time | Removal Efficiency | Light Source/Intensity | pH | Temperature | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WO3 nanosheets | U(VI) | 200 mg/L | 2 h | >95.6% | Xenon lamp/300 W | 4.8 | 293 K | [107] |

| La-doped WO3 | U(VI) | 40 mg/L | 1 h | 92.9 % | LED | 6.0 | 298 K | [108] |

| WO3−x | U(VI) | 100 mg/L | 4 h | 95.1% | AM 1.5 | 5 ± 0.1 | r.t. a | [109] |

| BVO/WNP-SC | U(VI) | 10 mg/L | 1.5 h | 99.5% | AM 1.5/100 mW/cm2 | 4.8 | r.t. a | [111] |

| ZnS/WO3 | U(VI) | 500 mg/L | 2 h | 93.4% | Xenon lamp/250 mW/cm2 | 6.0 | r.t. a | [112] |

| WO3/Ag | Hg(II) | 2 μm | 20 min | 97 ± 2% | Xenon lamp/100 mW/cm2 | 7.0 | r.t. a | [116] |

| Pd/WO3 (WP) | Cr(VI) | 0.4 mg/L | 1 h | >95% | n.a. b | n.a. b | 413 K | [117] |

| WO3@PVP | Cr(VI) | 10 mg/L | 4 h | >95% | Xenon lamp 400 nm/250 mW/cm2 | 2.5 | r.t. a | [118] |

| Z-scheme WO3/MIL- 100(Fe) | Cr(VI) | 5 mg/L | 100 min | 100% | LED/25 W | 2.0 | r.t. a | [119] |

| WO3-ZnIn2S | Cr(VI) | 25 mg/L | 0.5 h | 100% | Xenon lamp | 2.0 | r.t. a | [120] |

(a) r.t. refers to room temperature; (b) n.a. refers to not available.

For example, Zhai et al. [116] constructed a plasmonic Schottky heterojunction from WO3 nanosheets and well-dispersed Ag nanoparticles, forming an innovative “all-in-one” photoelectrochemical system. The efficient detection, removal, and recovery of Hg2+ cations from industrial wastewater could be achieved by the designed PC system, offering distinct advantages over traditional single-function approaches. This is especially useful for water-soluble hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)), which has been regarded as a Group 1 carcinogen per the IARC. The Cr(VI)-containing pollutants can cause respiratory and skin irritation and aquatic ecosystem destruction. Due to these environmental and health risks, the extraction and immobilization of Cr(VI) have become major focuses of scientific research. As previously reported, Liu [117] designed a Pd/WO3(WP) catalyst by supporting Pd nanoparticles on WO3 electrospun nanofibers. The optimized catalyst exhibited superior catalytic reduction activity for toxic Cr(VI) in the presence of formic acid (FA), which offered a novel insight for exploring diverse catalysts and facilitated the development of efficient catalysts for environmental Cr(VI) remediation. Chen et al. [118] synthesized PVP-coated WO3/PVP composites using hydrothermal synthesis. Owing to their good crystallinity, high CV potential, and abundant W5O2 surface defects, a superior photoreduction activity was obtained. The interaction between PVP and WO3 enhances their photocatalytic Cr(VI) reduction performance, offering a new way to improve WO3-based photocatalytic reduction. In addition, Wang et al. [119] developed a novel, efficient catalyst for pollutant removal and environmental sustainability. Using ball-milling, a series of Z-scheme WO3/MIL-100(Fe) (MxWy) composites were prepared. These composites exhibited high photocatalytic activity in reducing Cr(VI) and degrading bisphenol A (BPA) via photo-Fenton reactions under visible-light irradiation. Furthermore, as given in Figure 8c, Xu et al. [120] investigated a WO3 core–shell heterojunction decorated with ZnIn2S4 (ZIS) nanosheets. The systematic analysis revealed that the 1D/2D WO3@ZIS heterojunction achieved the highest removal efficiency for 25 mg/L Cr (VI) within 30 min, and 40 mg/L RhB was eliminated within 50 min, demonstrating outstanding redox capacities.

Figure 8.

(a) The mechanism for U(VI) adsorption and photoreduction by W0.9La0.1O3−x (from ref. [107], with permission). (b) Illustration of the possible mechanism of SWRS in treating complex wastewater with OTC and UO22+, pH = 4.8, and simultaneous electricity production under sunlight illumination (from ref. [109], with permission). (c) Illustration of the charge transfer process of the photogenerated electrons (e−) and holes (h+) in the WO3 @ZIS (S-WO3-2 h) heterostructure and the photocatalytic mechanism for Cr (VI) reduction under visible-light irradiation (from ref. [118], with permission).

4. Further Perspectives and Challenges

Despite these promising demonstrations, the practical implementation of WO3 in these diverse fields faces several persistent challenges:

First, the recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs remains a major bottleneck, limiting the quantum efficiency and reaction rates. Although common modification strategies, such as heterostructure construction, doping, and morphology control, have been employed to enhance charge separation, the design of highly efficient WO3-based systems with spatially directed charge flow for specific reactions (e.g., in situ redox reaction, separate oxidation–reduction reactions at different sites, and selective yield of target products) is still in its infancy. The synchronous modification of heterostructure construction and heteroatom doping, as discussed in this review, can introduce polarization-driven band bending with specific active site exposure to suppress charge carrier recombination and accelerate direct charge transfer toward targeted reactions.

Second, the selectivity and stability of WO3 in complex reaction conditions need to be improved. Especially in organic synthesis, severe challenges still exist in achieving high product selectivity without over-oxidation or undesired side reactions. For environmental pollution purification, the presence of competing ions or organic matter can poison the active sites on the catalyst surface or scavenge reactive species. Developing effective catalysts or modification strategies (e.g., molecular cocatalysts, selective adsorbates, or defect engineering) may offer pathways to enhance both activity and selectivity in green chemical conversion.

Third, the scalability and long-term durability of WO3-based photo(electro)-catalytic systems under operational conditions, including extreme pH, high ion strength, and continuous illumination, are not yet fully established. Corrosion and surface fouling can lead to performance decay over long-term usage. Inspired by previous studies, developing protective layers or hybrid structures with conductive and chemically stable scaffolds (e.g., carbon materials and conductive polymers) can effectively improve the operational longevity.

Fourth, the response and utilization of solar energy, especially for visible light, remain suboptimal. Although WO3 absorbs visible light, the potential of its CB edge cannot meet the demand for reduction reactions without external bias or sensitization. Coupling WO3 with narrow-bandgap semiconductors or plasmonic metals can significantly extend light absorption and enhance redox capability, thereby enabling more efficient solar-driven reactions.

In our opinion, a future research hotspot will be tailoring the microstructure of WO3 at an atomic level. Multiple strategies, including morphology control, defect engineering, heterostructure fabrication, and so on, will be combined synergistically to tune energy levels and accelerate interfacial charge separation. In terms of actual applications, WO3 catalysts are expected to move beyond traditional pollutant degradation into solar fuel generation, including CO2 reduction, N2 fixation, H2 evolution, and organic synthesis. Interdisciplinary integration, like in situ characterization, theoretical simulations, and artificial intelligence, will be harnessed to decode structure–property relationships and expedite the discovery of novel, efficient catalysts. Ultimately, translating powder systems into robust thin-film electrodes or monolithic reactors will constitute the decisive leap from material development to practical devices. To sum up, by integrating materials science, chemistry, and engineering with deeper mechanistic insights to drive rational design, WO3-based catalysts play an ever-more-critical role in the future energy transition and environmental remediation.

5. Conclusions

Recently, advanced investigations into PC and PEC conversion have achieved notable success, particularly for the usage of WO3-based materials as a promising candidate. This review summarizes and offers an overview of advanced development and applications of WO3-based photo(electro)-catalysts in green organic synthesis and hazardous pollutant removal, including redox organic conversion, POP decomposition, and elimination of highly soluble toxic metal ions. The growing concern about carbon neutrality goals necessitates innovative green and efficient solutions, such as PC and PEC techniques. To provide better guidance for researchers, the advances in research on WO3-based photo(electro)-catalysts are systematically analyzed with regard to construction strategies and various application scenarios. Most importantly, common functionalization methods and possible reaction mechanisms for WO3 are introduced in depth, especially for the investigation of key influencing factors. Additionally, diverse applications of WO3 for the elimination of organic pollutants (e.g., tetracycline, phenol, and high-polymer wastes) and green organic synthesis (i.e., oxidation, reduction, and other reactions) are also intentionally discussed to underscore their vast potential in photo(electro)-catalytic performance. In conclusion, WO3-based materials offer potential possibilities for developing PC and PEC strategies for green chemical transformation. Collectively, these findings furnish a robust knowledge base for the deliberate engineering of next-generation WO3 catalysts and will stimulate future breakthroughs.

Author Contributions

L.B., S.Z. and L.T. conducted the information search and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and S.Z., K.X. and C.Z. discussed and revised parts of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 22106047).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Conk, R.J.; Stahler, J.F.; Shi, J.X.; Yang, J.; Lefton, N.G.; Brunn, J.N.; Bell, A.T.; Hartwig, J.F. Polyolefin waste to light olefins with ethylene and base-metal heterogeneous catalysts. Science 2024, 385, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.B.; Navale, Y.H.; Navale, S.T.; Stadler, F.J.; Ramgir, N.S.; Patil, V.B. Hybrid polyaniline-WO3 flexible sensor: A room temperature competence towards NH3 gas. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 288, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Deng, C.; Tang, D.; Ding, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sheng, H.; Ji, H.; Song, W.; Ma, W.; Chen, C.; et al. α-Fe2O3 as a versatile and efficient oxygen atom transfer catalyst in combination with H2O as the oxygen source. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zuo, L.; Guo, Z.; Yang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, X.; Wu, L.; Tang, Z. Al2O3-coated BiVO4 photoanodes for photoelectrocatalytic regioselective C-H activation of aromatic amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202315478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basak, A.; Karak, S.; Banerjee, R. Covalent organic frameworks as porous pigments for photocatalytic metal-Free C-H borylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 7592–7599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Einaga, H. WO3-based materials for photocatalytic and photoelectrocatalytic selective oxidation reactions. ChemCatChem 2023, 15, e202300723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; An, Z.; Li, M.; Guo, L.-H. Synthesis, functionalization and photoelectrochemical immunosensing application of WO3-based semiconductor materials. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 165, 117149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenderich, K.; Mul, G. Methods, mechanism, and applications of photodeposition in photocatalysis: A review. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14587–14619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Sun, Y.-D.; Ma, X.-J.; Jin, F.-X.; Zhang, F.-Y.; Han, W.-G.; Shen, B.-X.; Guo, S.-Q. A review on WO3-based composite photocatalysts: Synthesis, catalytic mechanism and diversified applications. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 3441–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, T. Oxygen vacant semiconductor photocatalysts. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelli, D.; Dondi, D.; Fagnoni, M.; Albini, A. Photocatalysis. A multi-faceted concept for green chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1999–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, M.D.; Lee, J.S. Recent theoretical progress in the development of photoanode materials for solar water splitting photoelectrochemical cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 10632–10659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamrai, J.; Ghosh, I.; Savateev, A.; Antonietti, M.; König, B. Photo-Ni-dual-catalytic C(sp2)-C(sp3) cross-coupling reactions with mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride as a heterogeneous organic semiconductor photocatalyst. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 3526–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, T.; Mushtaq, M.A.; Wu, S.; Xiang, X.; Yan, D. Research Progress in Organic Synthesis by Means of Photoelectrocatalysis. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Cui, W. Metal free and efficient photoelectrocatalytic removal of organic contaminants over g-C3N4nanosheet films decorated with carbon quantum dots. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 56335–56343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, C. Heterophase junction effect on photogenerated charge separation in photocatalysis and photoelectrocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2025, 58, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wei, A.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y. Achieving high selectivity in photoelectrochemical oxidation of glycerol on WO3 nanosheets coupled with TiO2 nanorods arrays. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 332, 125779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Huang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, J.S.; Wu, Y. Harnessing visible-light energy for unbiased organic photoelectrocatalysis: Synthesis of N-bearing fused rings. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Hassani, A.; Zhou, M. Non-TiO2-based photoanodes for photoelectrocatalytic wastewater treatment: Electrode synthesis, evaluation, and characterization. EES Catal. 2025, 3, 921–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noël, T.; Zysman-Colman, E. The promise and pitfalls of photocatalysis for organic synthesis. Chem Catal. 2022, 2, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Huang, N.; Guan, Y.; Yang, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, B.; Wang, H. A constructed 3D porous hierarchical micro-flower WO3/CdS S-scheme heterojunction for boosting photocatalytic H2O2 production and photoelectrochemical cell performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 14161–14171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerton, T.A. UV-Absorption-The primary process in photocatalysis and some practical consequences. Molecules 2014, 19, 18192–18214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, Z.; Lin, T.; Yin, H.; Lü, X.; Wan, D.; Xu, T.; Zheng, C.; Lin, J.; Huang, F.; et al. Core-shell nanostructured “black” rutile titania as excellent catalyst for hydrogen production enhanced by sulfur doping. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 17831–17838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Yu, P.Y.; Mao, S.S. Increasing solar absorption for photocatalysis with black hydrogenated titanium dioxide nanocrystals. Science 2011, 331, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhethanabotla, V.C.; Russell, D.R.; Kuhn, J.N. Assessment of mechanisms for enhanced performance of Yb/Er/titania photocatalysts for organic degradation: Role of rare earth elements in the titania phase. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 202, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-X.; Shi, F.-B.; Zhang, T.; Wu, H.-S.; Sun, L.-D.; Yan, C.-H. Ytterbium stabilized ordered mesoporous titania for near-infrared photocatalysis. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 8109–8111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, R.; Chen, L.; Li, K.; Dong, F. Advances and challenges of photocatalytic technology for air purification. Natl. Sci. Open 2022, 1, 20220025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htet, H.T.; Jung, Y.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S. Enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting using NiMoO4/BiVO4/Sn-Doped WO3 double heterojunction photoanodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 52383–52392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Xing, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhou, W. Carbon doping and oxygen vacancy-tungsten trioxide/Cu3SnS4 S-Scheme heterojunctions for boosting visible-light-driven photocatalytic performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 18296–18306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Jia, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, S.; Hao, D.; Ni, B. High carrier separation efficiency for a defective g-C3N4 with polarization effect and defect engineering: Mechanism, properties and prospects. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 5432–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Y.-L.; Liu, P.; Peng, X.; Pan, Y.-X. Efficient photocatalysis triggered by thin carbon layers coating on photocatalysts: Recent progress and future perspectives. Sci. China Chem. 2020, 63, 1416–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, F.; Wang, G.; Lv, M.; Bai, J.; Li, Y.; Hou, T.; Li, Y. Interfacial dual active centers bridged by oxygen vacancies promoting photocatalytic oxidation of methane. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2025, 365, 124934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Zhong, A.; Tang, Q.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z. Oxygen vacancies induce boosted photocarriers dynamics in WO3/Ti3C2 micro-nano structures with enriched 2D-2D interfaces for trimethylamine abatement. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sett, S.; Raychaudhuri, A.K. Effective separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs by radial field facilitates ultrahigh photoresponse in single semiconductor nanowire photodetectors. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 22808–22816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Mao, K.; Li, J.; Zhai, G.; Wu, D.; Liu, D.; Long, R.; Xiong, Y. Modulating chloride adsorption for efficient chloride-mediated methane conversion over tungsten oxide photoanode. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 6058–6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadpour, F.; Amani, A.M. Photocatalytic systems: Reactions, mechanism, and applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 20609–20645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Cui, L. Mg-Pd coexisted adsorption and activation tandem sites for methane photocoupling into ethane by oxygen medium. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, M.; Rane, S.; Jagtap, S. WO3: A review of synthesis techniques, nanocomposite materials and their morphological effects for gas sensing application. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2023, 46, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Xiang, W.; Shi, J.; Ji, Y. Recent advances in the heterogeneous photocatalytic hydroxylation of benzene to phenol. Molecules 2022, 27, 5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulebekov, Y.; Orazov, Z.; Satybaldiyev, B.; Snow, D.D.; Schneider, R.; Uralbekov, B. Reaction steps in heterogeneous photocatalytic oxidation of toluene in gas phase-A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayegan, Z.; Lee, C.-S.; Haghighat, F. TiO2 photocatalyst for removal of volatile organic compounds in gas phase—A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 2408–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, N.; Huang, J.-Y.; He, S.; Hanggai, W.; Chao, L.-M. Applications of optical control materials based on localized surface plasmon resonance effect in smart windows. Tungsten 2024, 6, 711–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z. Oxygen-deficient WO3 for stable visible-light photocatalytic degradation of acetaldehyde within a wide humidity range. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 491, 152193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Liu, X.; Xie, J.; Li, S.; Huang, K.; Fan, X.; Long, C.; Zuo, L.; Zhao, W.; et al. Steering photooxidation of methane to formic acid over a priori screened supported catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 16039–16051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Cui, J.; Sun, J. Hydrothermal synthesis of self-assembled hierarchical tungsten oxides hollow spheres and their gas sensing properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 10108–10114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]