Selective Catalytic Oxidation of Lean-H2S Gas Stream to Elemental Sulfur at Lower Temperature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

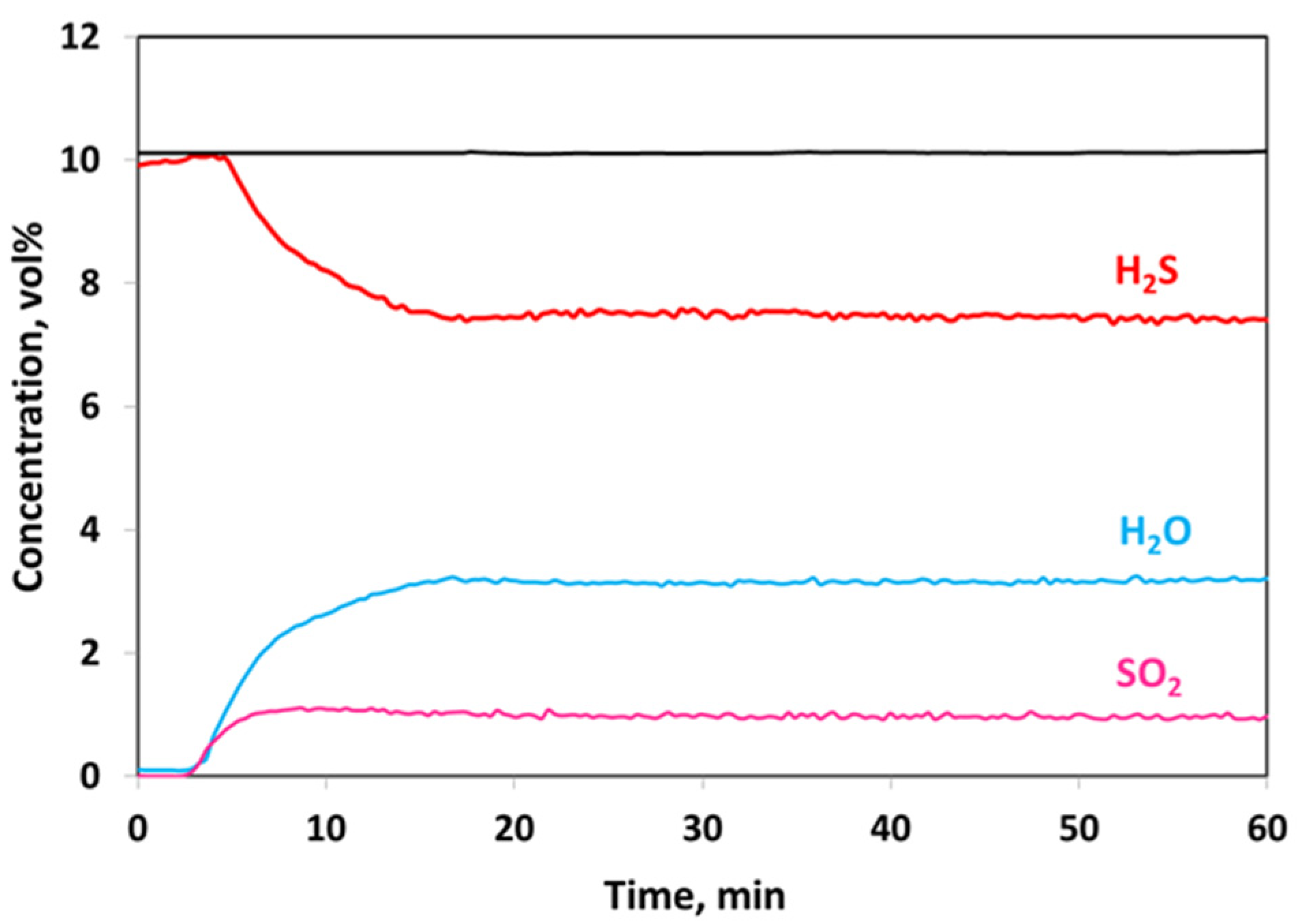

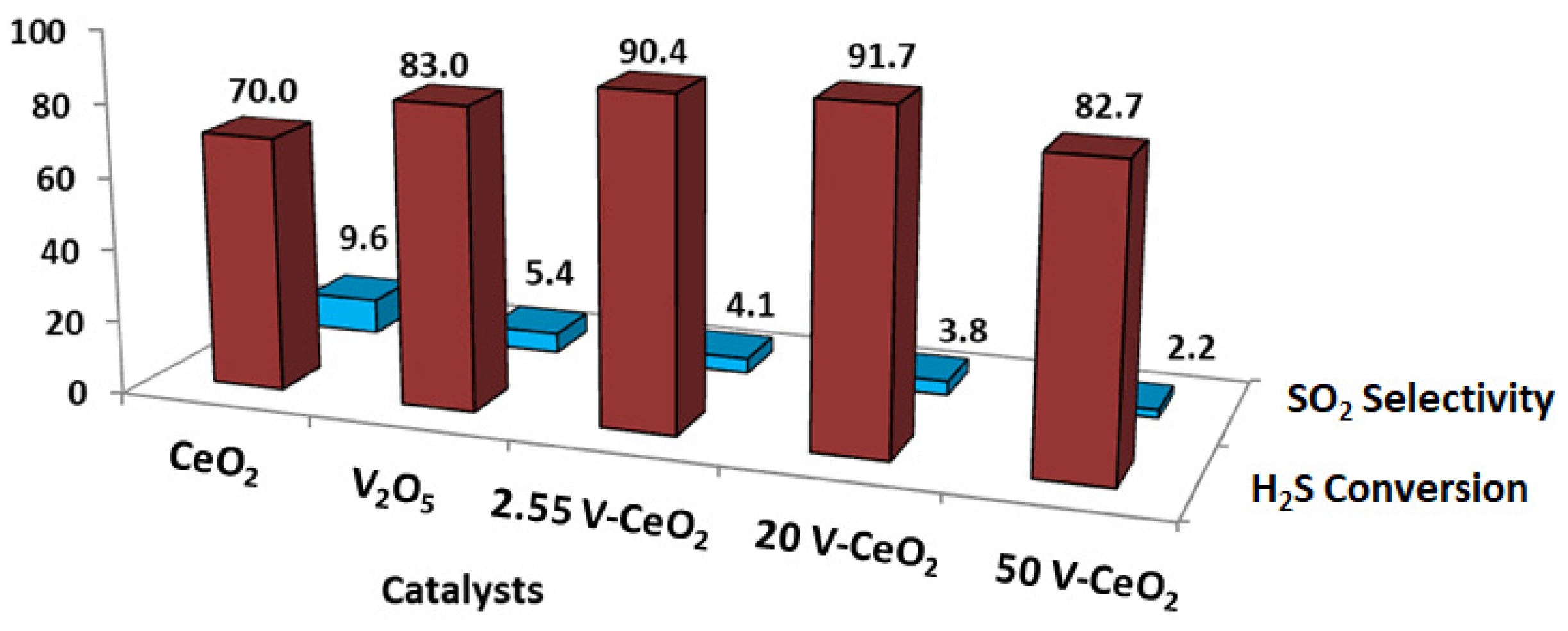

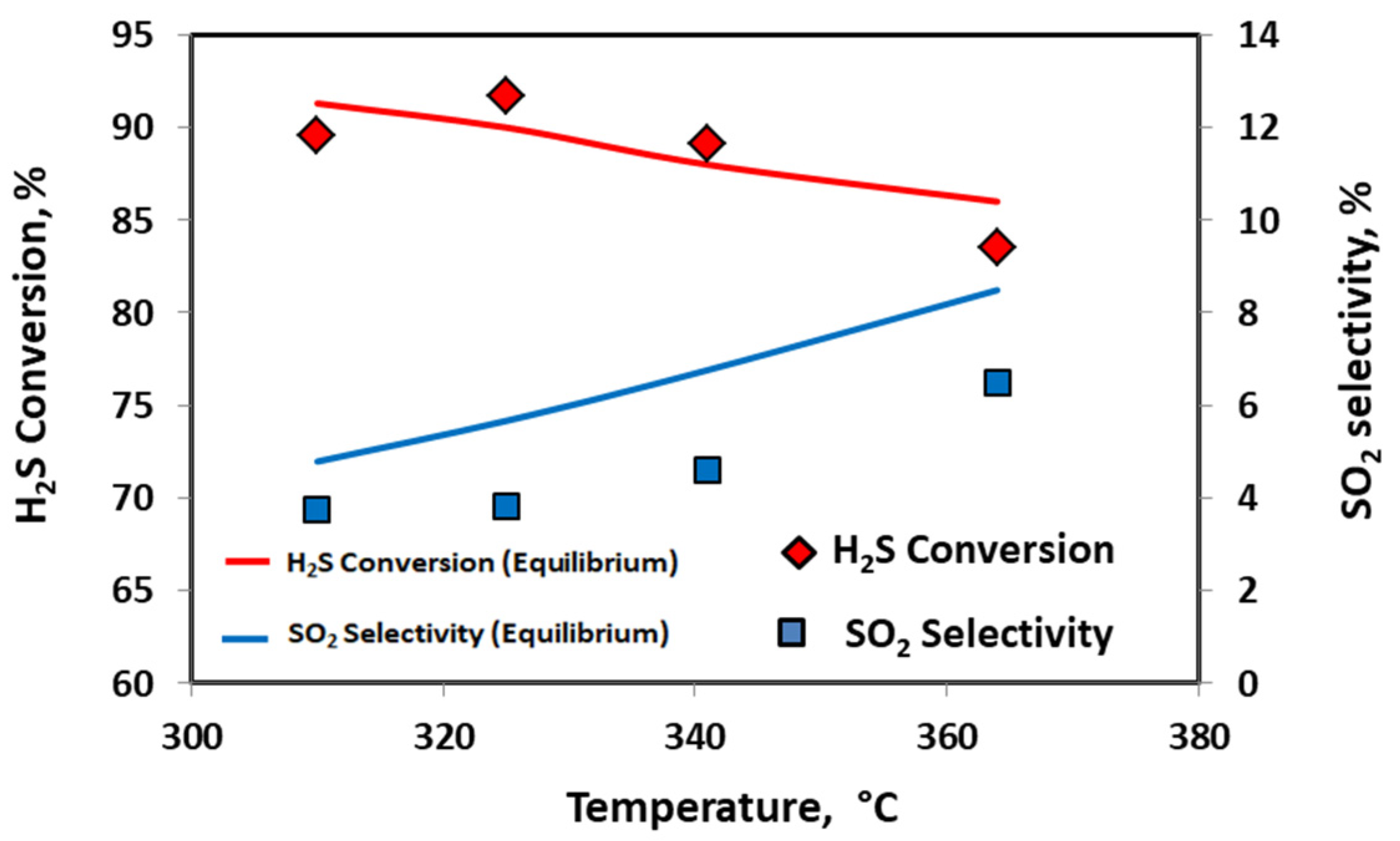

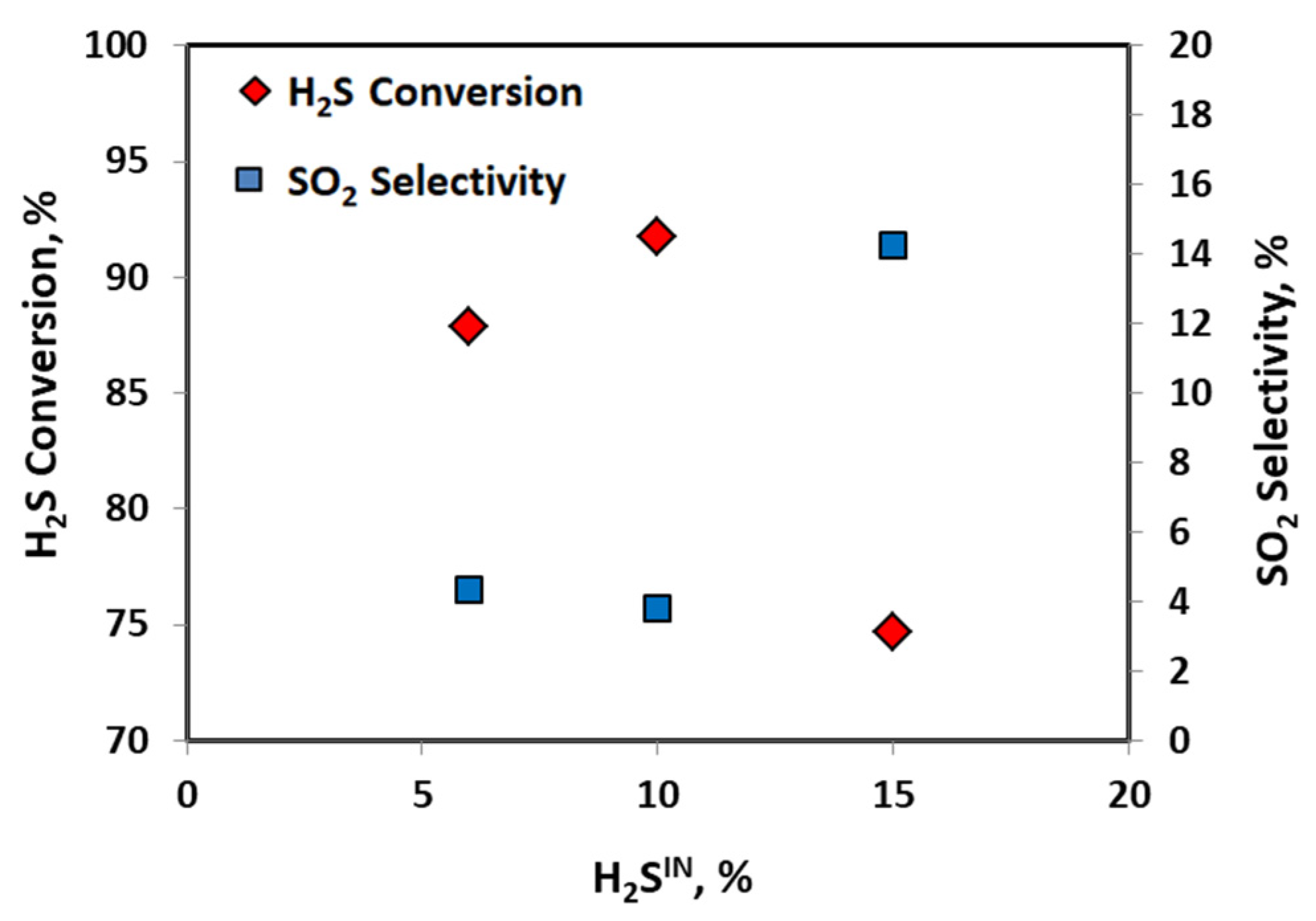

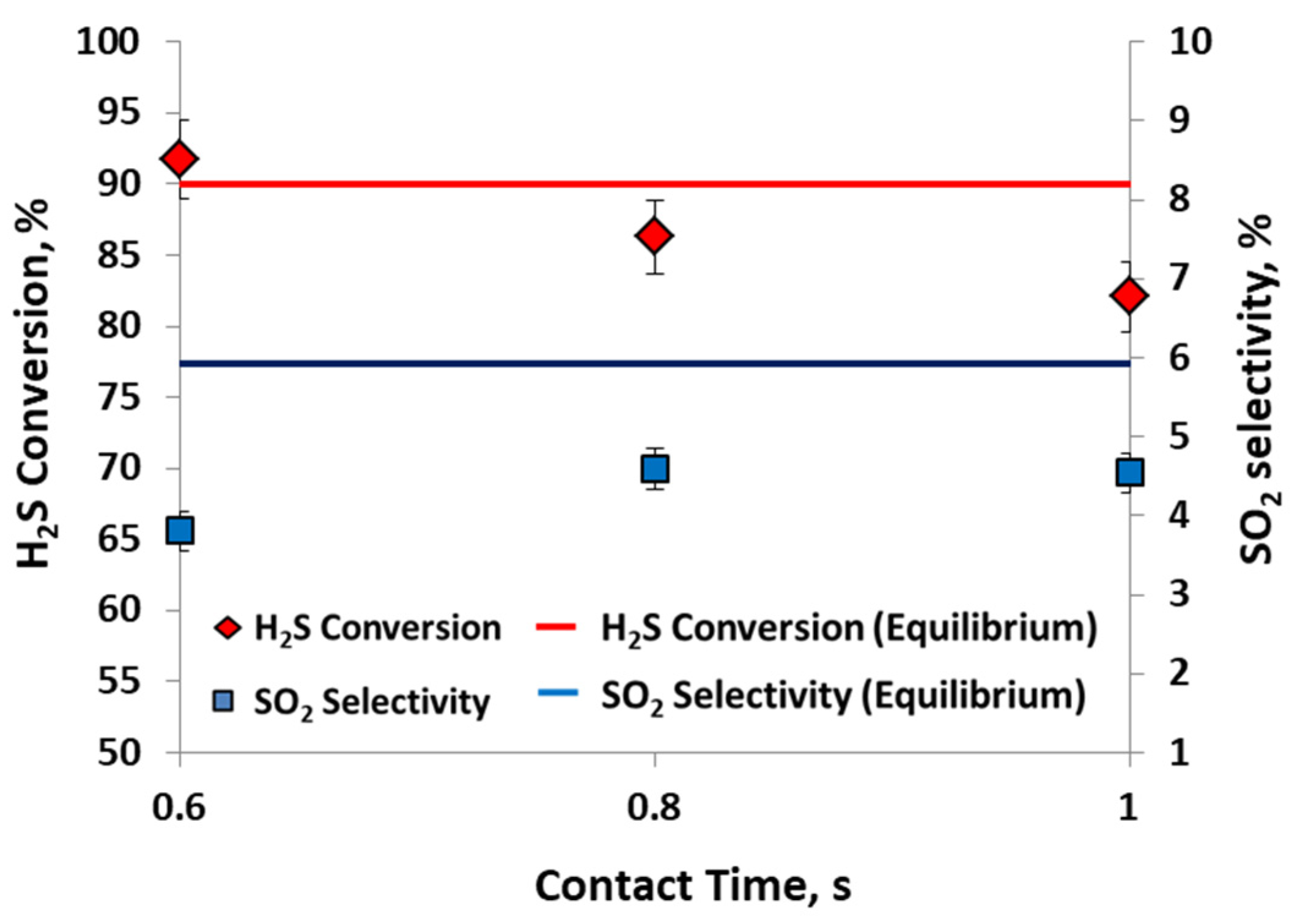

2.1. Catalytic Activity Test

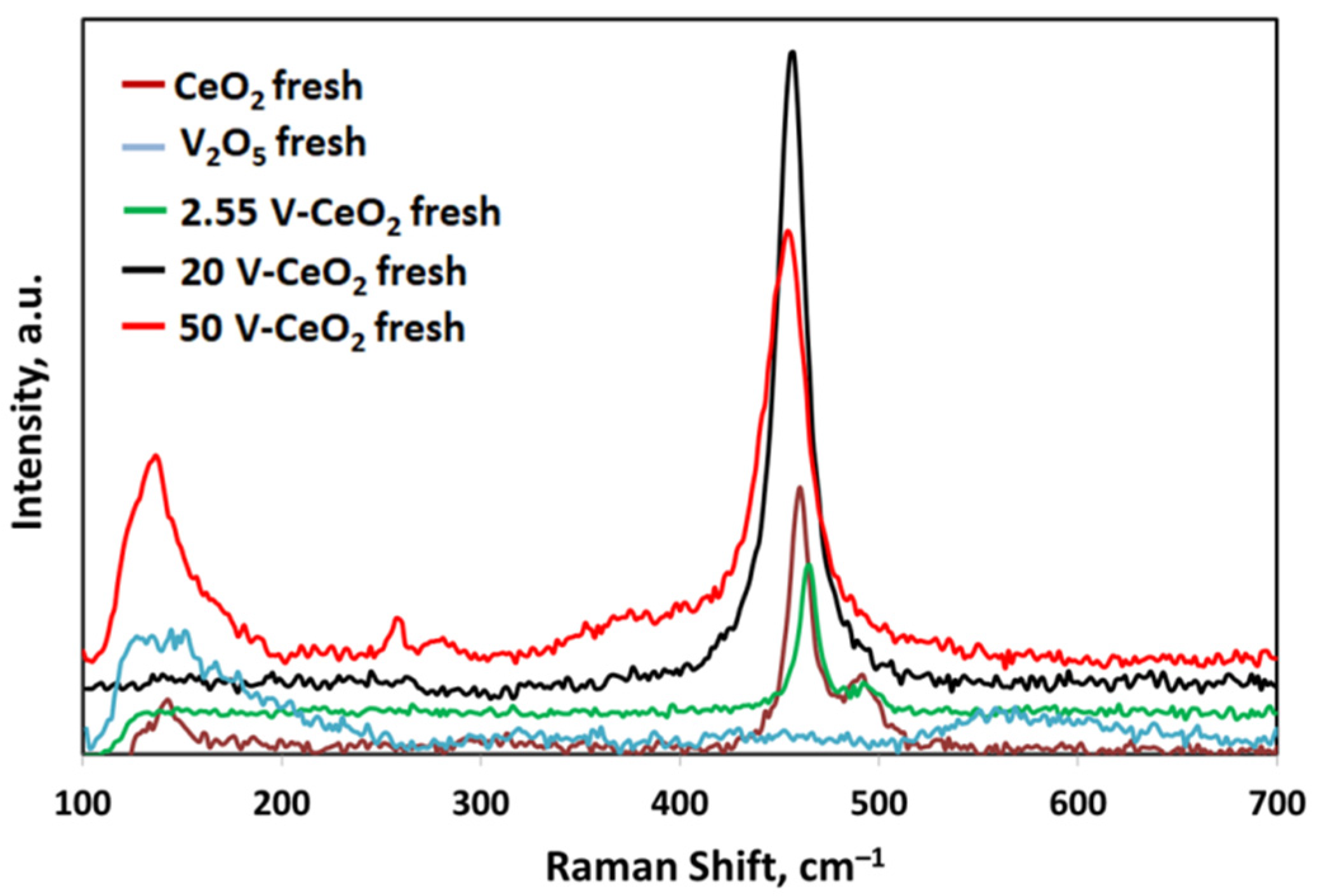

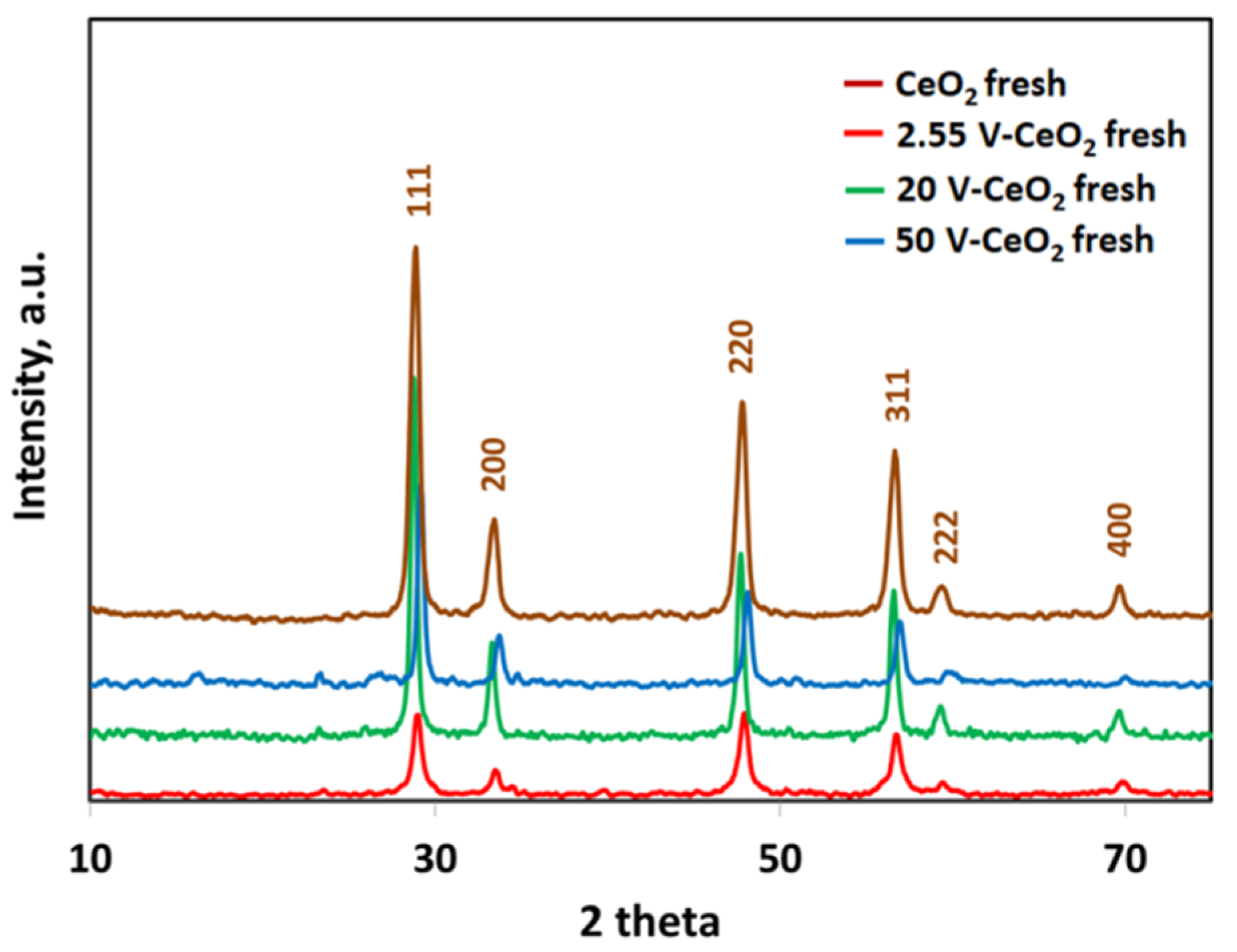

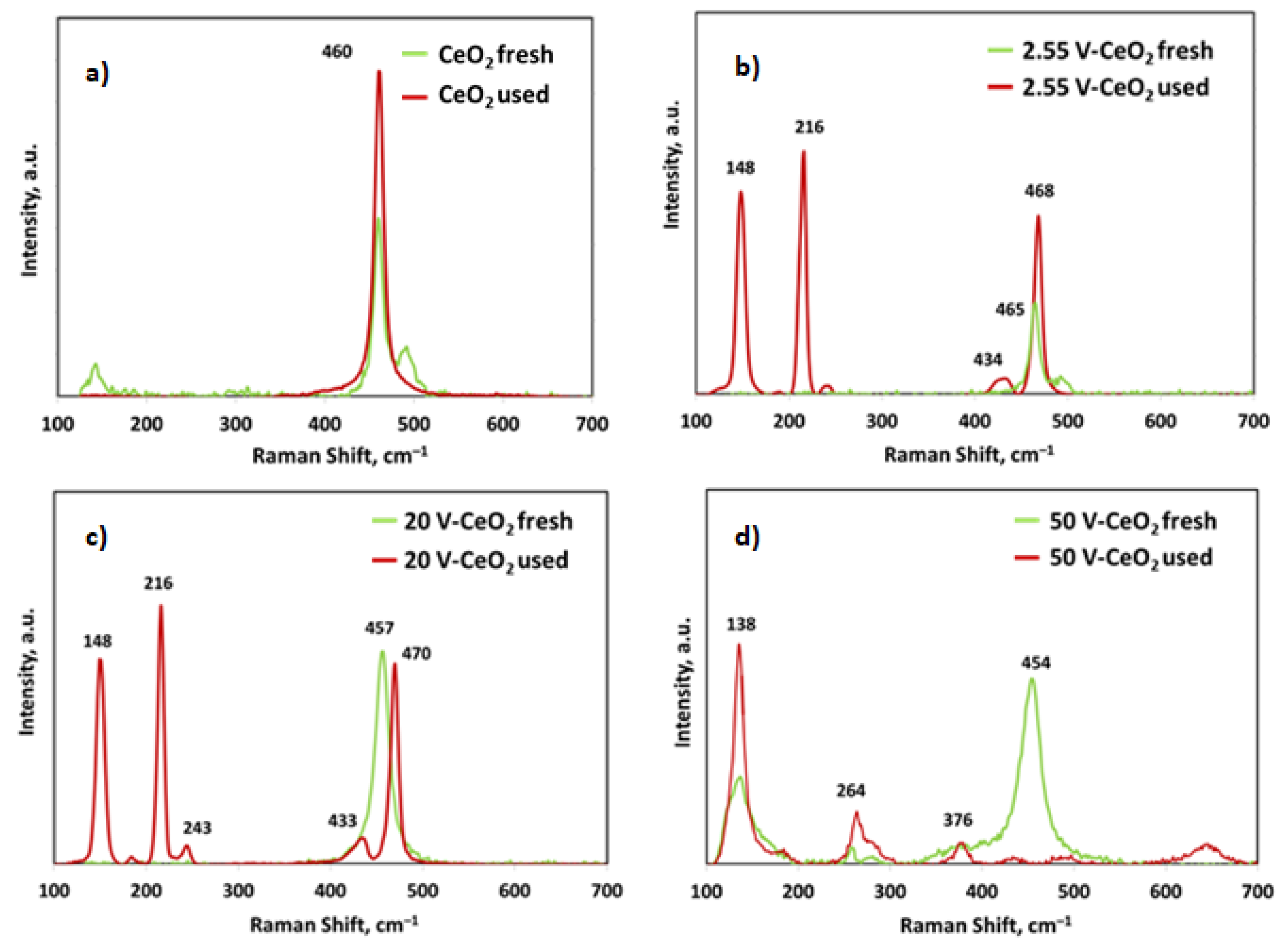

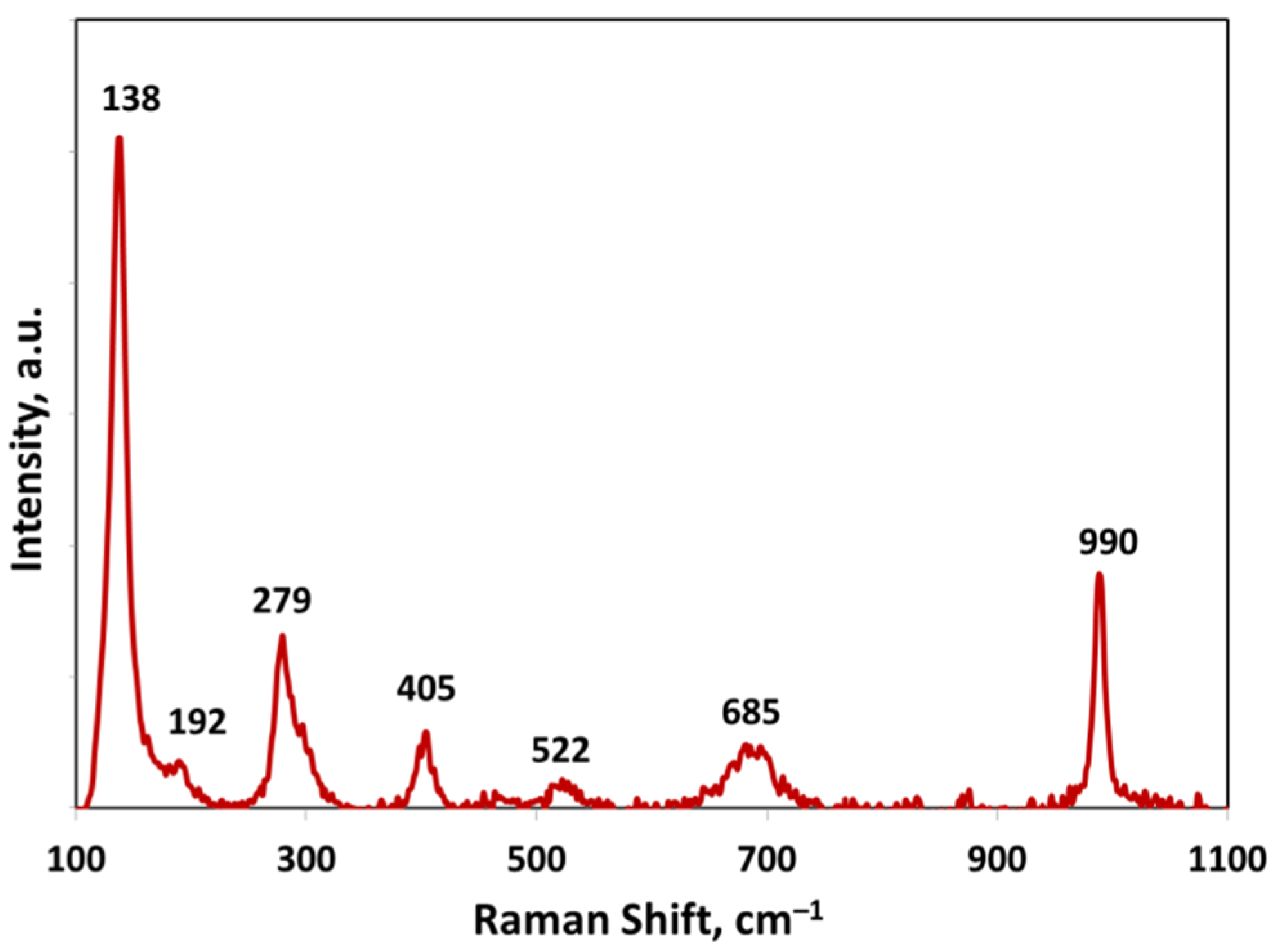

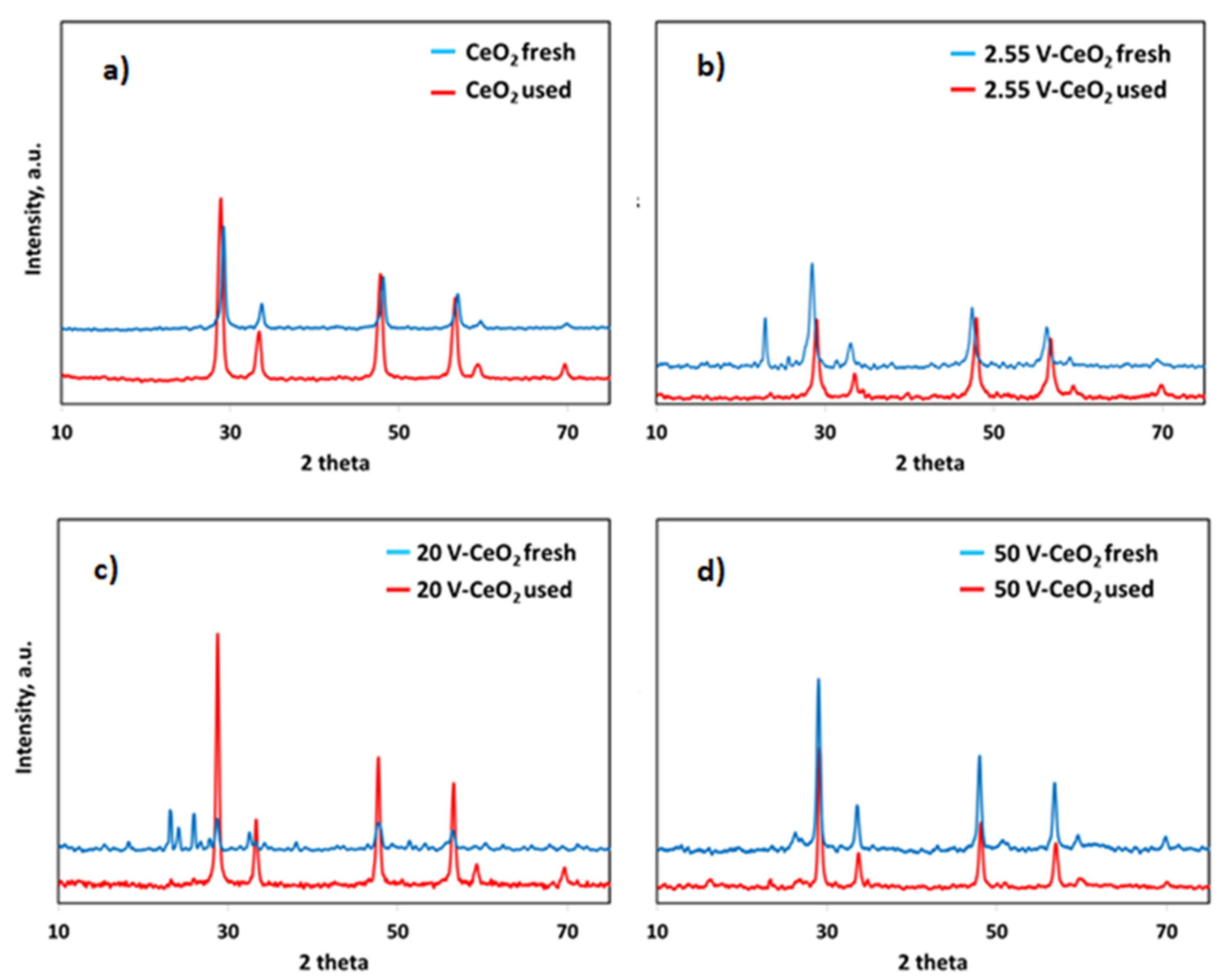

2.2. Catalyst Characterization

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Catalyst Preparation and Characterization

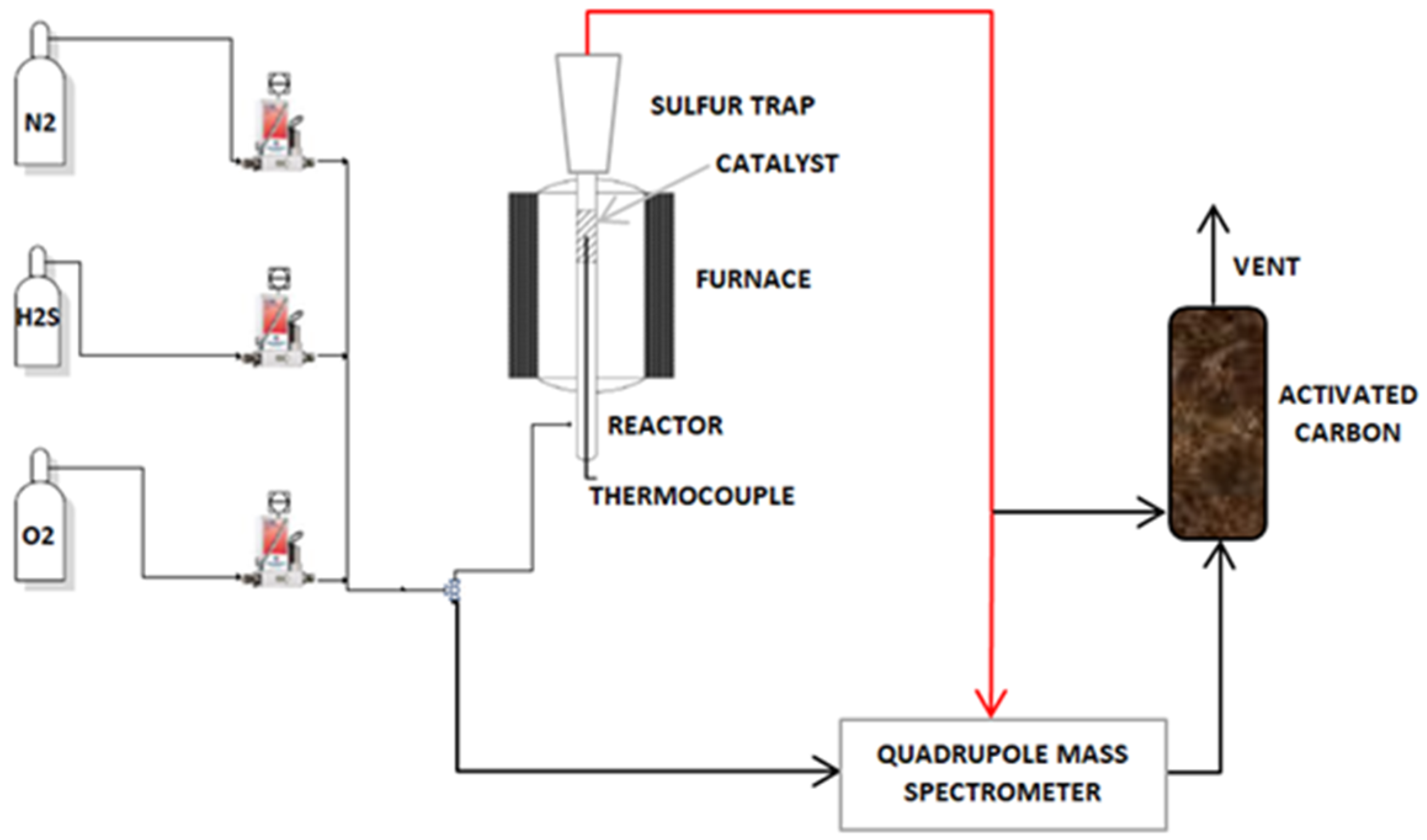

3.2. Experimental Apparatus

Calibration Procedure

- (1)

- Report in a table the partial pressure of the all-mass fragment for each concentration of the component to calibrate;

- (2)

- Construct the matrix of interference and the response factors table relatively for the component you are calibrating;

- (3)

- Calculate the concentrations of the component calibrated by considering the relative interference of other species on the component to calibrate and correcting the measure by its response factor.

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forzatti, P.; Lietti, L. Catalyst deactivation. Catal. Today 1999, 52, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Investigation on a new liquid redox method for H2S removal and sulfur recovery with heteropoly compound. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2003, 31, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Yan, R.; Koe, L.C.; Wang, X. Combined effect of adsorption and biodegradation of biological activated carbon on H2S biotrickling filtration. Chemosphere 2007, 66, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seredych, M.; Bandosz, T.J. Sewage sludge as a single precursor for development of composite adsorbents/catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2007, 128, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasyerli, S.; Dogu, G.; Ar, I.; Dogu, T. Dynamic analysis of removal and selective oxidation of H2S to elemental sulfur over Cu–V and Cu–V–Mo mixed oxides in a fixed bed reactor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2004, 59, 4001–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmawgoud, H.A.; Elshiekh, M.; Abdelkreem, M.; Khalil, S.A.; Alsabagh, A.M. Optimization of petroleum crude oil treatment using hydrogen sulfide scavenger. Egypt. J. Pet. 2019, 28, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, J.H.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, J.D.; Jun, J.H.; Park, N.K.; Ryu, S.O.; Lee, T.J. The study on the selective oxidation of H2S over the mixture zeolite NaX-WO3 catalysts. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2004, 21, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.D.; Han, G.B.; Park, N.K.; Ryu, S.O.; Lee, T.J. The selective oxidation of H2S on V2O5/zeolite-X catalysts in an IGCC system. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2006, 12, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wiheeb, A.D.; Shamsudin, I.K.; Ahmad, M.A.; Murat, N.M.; Kim, J.; Othman, M.R. Present technologies for hydrogen sulfide removal from gaseous mixtures. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2013, 29, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, N.; Pham-Huu, C.; Crouzet, C.; Ledoux, M.J.; Savin-Poncet, S.; Nougayrede, J.B.; Bousquet, J. Direct oxidation of H2S into S: New catalysts and processes based on SiC support. Catal. Today 1999, 53, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, Y.; Qu, S.; Da, J.; Hao, Z. H2S-selective catalytic oxidation: Catalysts and processes. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 1053–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, A.A.; Marshneva, V.I.; Shepotko, M.L. The comparison study of the catalytic activity. Mechanism of the interactions between H2S and SO2 on some oxides. Appl. Catal. A 2003, 244, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.T.; Hyang, M.Y.; Cheng, W.D. Vanadium-based mixed-oxide catalysts for selective oxidation of hydrogen sulfide to sulfur. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1996, 35, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.W.; Byung, B.H.; Ju, W.D.; Kim, M.I.; Kim, K.H.; Woo, H.C. Selective oxidation of hydrogen sulfide containing excess water and ammonia over Bi-V-Sb-O catalysts. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2005, 22, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinkin, P.; Kovalenko, O.; Lapina, O.; Khabibulin, D.; Kundo, N. Kinetic peculiarities in the low-temperature oxidation of H2S over vanadium catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2002, 178, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, M.D.; Jimenez-Jimenez, J.; Concepcion, P.; Jimenez- Lopez, A.; Rodrıguez-Castellon, E.; Lopez Nieto, J.M. Selective oxidation of H2S to sulfur over vanadia supported on mesoporous zirconium phosphate heterostructure. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 92, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, V.; Barba, D.; Ciambelli, P. Screening of catalysts for H2S abatement from biogas to feed molten carbonate fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, V.; Barba, D. Low temperature catalytic oxidation of H2S over V2O5/CeO2 catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 21524–21530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, V.; Barba, D. Vanadium-ceria catalysts for H2S abatement from biogas to feed to MCFC. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, V.; Barba, D.; Gerardi, V. Honeycomb-structured catalysts for the selective partial oxidation of H2S. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 111, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, V.; Barba, D. Honeycomb V2O5-CeO2 catalysts for H2S abatement from biogas by direct selective oxidation to sulfur at low temperature. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2015, 43, 1957–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Ge, J. Structural, redox and acid–base properties of V2O5/CeO2 catalyst. Thermochim. Acta 2006, 451, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, V.S.; López, E.F.; Panizza, M.; Resini, C.; Amores, J.M.G.; Busca, G. Characterization of cubic ceria–zirconia powders by X-ray diffraction and vibrational and electronic spectroscopy. Solid State Sci. 2003, 5, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L. Controlled synthesis of CeO2 nanorods by a solvothermal method. Nanotechnology 2005, 16, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhika, T.; Sugunan, S. Structural and catalytic investigation of vanadia supported on ceria promoted with high surface area rice husk silica. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2006, 250, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Singh, B.; Gupta, M.K.; Mishra, S.K.; Mittal, R.; Sastry, P.U.; Rolsc, S.; Lal Chaplot, S. Anomalous lattice behavior of vanadium pentaoxide (V2O5): X-ray diffraction, inelastic neutron scattering and ab initio lattice dynamics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 17967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Xu, L.; Guo, X.T.; Lv, T.T.; Pang, H. Vanadium sulfide based materials: Synthesis, energy storage and conversion. J. Mater. Chem. 2020, 8, 20781–20802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgrado, J.P.; Soriano, M.D.; Jimenez, J. Operando XAS and Raman study on the structure of a supported vanadium 409 oxide catalyst during the oxidation of H2S to sulfur. Appl. Catal. B 2010, 92, 271–279, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, W.; Chen, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Yang, Q.; Hu, N.; Suo, Y.; Wang, J. Layered vanadium (IV) 414 disulfide nanosheets as a peroxidase-like nanozyme for colorimetric detection of glucose. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Shao, M.; Shao, Y.; Yang, M.; Xu, J.; Kwok, C.T.; Shi, X.; Lu, Z.; Pan, H. Ultra-high electrocatalytic activity of VS2 nanoflowers for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 15080–15086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.C. The vibrational spectra and structure of the vanadyl ion in aqueous solution. Inorg. Chem. 1963, 2, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Su, D.; Zhang, W.; Bao, W.; Wang, G. A nitrogen–sulfur co-doped porous graphene matrix as a sulfur immobilizer for high performance lithium–sulfur batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 17381–17393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, M.Y.; Kalinkin, A.V.; Pashis, A.V.; Sorokin, A.M. Interaction of Al2O3 and CeO2 Surfaces with SO2 and SO2 + O2 studied by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 11712–11719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, I.B.; Singh, V.; Lakhanpal, M. Study of thermal decomposition of ammonium cerium sulphate. J. Therm. 1992, 38, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No Catalyst | 20 V-CeO2 | Equilibrium | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2S Conversion, % | 26 (±1.5) | 92 (±1.5) | 90 |

| SO2 Selectivity, % | 38.5 (±2) | 4 (±2) | 6 |

| SO2, vol% | 1 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| H2SIN, vol% | xH2S, % | xH2S Eq., % | S SO2, % | sSO2 Eq., % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 88 (±1.5) | 89 | 4.4 (±2) | 4 |

| 10 | 92 (±1.5) | 90 | 4 (±2) | 6 |

| 15 | 75 (±1.5) | 90 | 14 (±2) | 9 |

| Sample | V2O5 Nominal wt% | % V2O5 Measured wt% |

|---|---|---|

| 2.55 V-CeO2 | 2.55 | 2.7 |

| 20 V-CeO2 | 20 | 22 |

| 50 V-CeO2 | 50 | 51 |

| Sample | CeO2 | V2O5 | 2.55 V-CeO2 | 20 V-CeO2 | 50 V-CeO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | 29 | 8 | 25 | 22 | 20 |

| Used | 17 | 2 | 17 | 4 | 14 |

| Sample | Fresh | Used |

|---|---|---|

| CeO2 | 13 | 21 |

| 2.55 V-CeO2 | 16 | 19 |

| 20 V-CeO2 | 18 | 19 |

| 50 V-CeO2 | 24 | 25 |

| Operating Conditions | |

|---|---|

| Temperature | 200–367 °C |

| Contact Time | 0.6–1 s |

| Catalyst Volume | 3 cm3 |

| Total Flow Rate | 180–300 Ncc·min−1 |

| GHSV | 3600–6000 h−1 |

| H2SIN concentration | 6–15 vol% |

| O2/H2S | 0.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barba, D.; Vaiano, V.; Palma, V. Selective Catalytic Oxidation of Lean-H2S Gas Stream to Elemental Sulfur at Lower Temperature. Catalysts 2021, 11, 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11060746

Barba D, Vaiano V, Palma V. Selective Catalytic Oxidation of Lean-H2S Gas Stream to Elemental Sulfur at Lower Temperature. Catalysts. 2021; 11(6):746. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11060746

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarba, Daniela, Vincenzo Vaiano, and Vincenzo Palma. 2021. "Selective Catalytic Oxidation of Lean-H2S Gas Stream to Elemental Sulfur at Lower Temperature" Catalysts 11, no. 6: 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11060746

APA StyleBarba, D., Vaiano, V., & Palma, V. (2021). Selective Catalytic Oxidation of Lean-H2S Gas Stream to Elemental Sulfur at Lower Temperature. Catalysts, 11(6), 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11060746