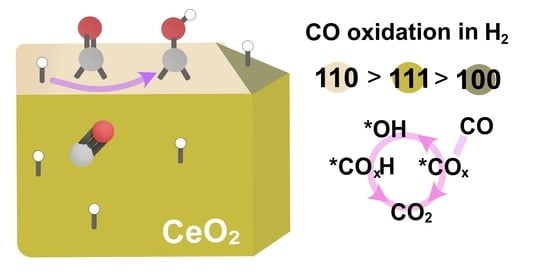

Investigations of the Effect of H2 in CO Oxidation over Ceria Catalysts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of Ceria Surfaces

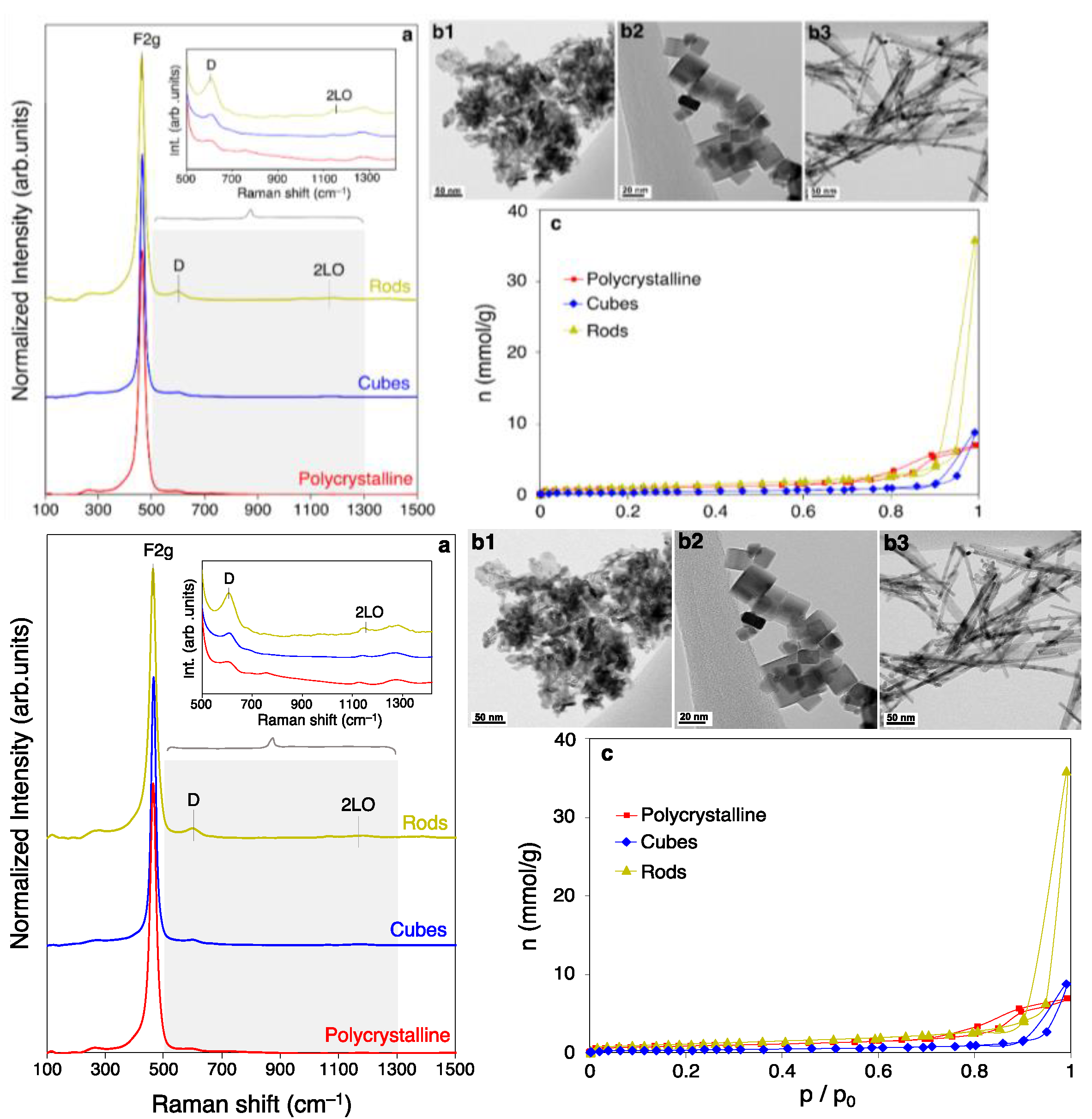

2.1.1. Physicochemical Features of Nano-Shaped Ceria Samples

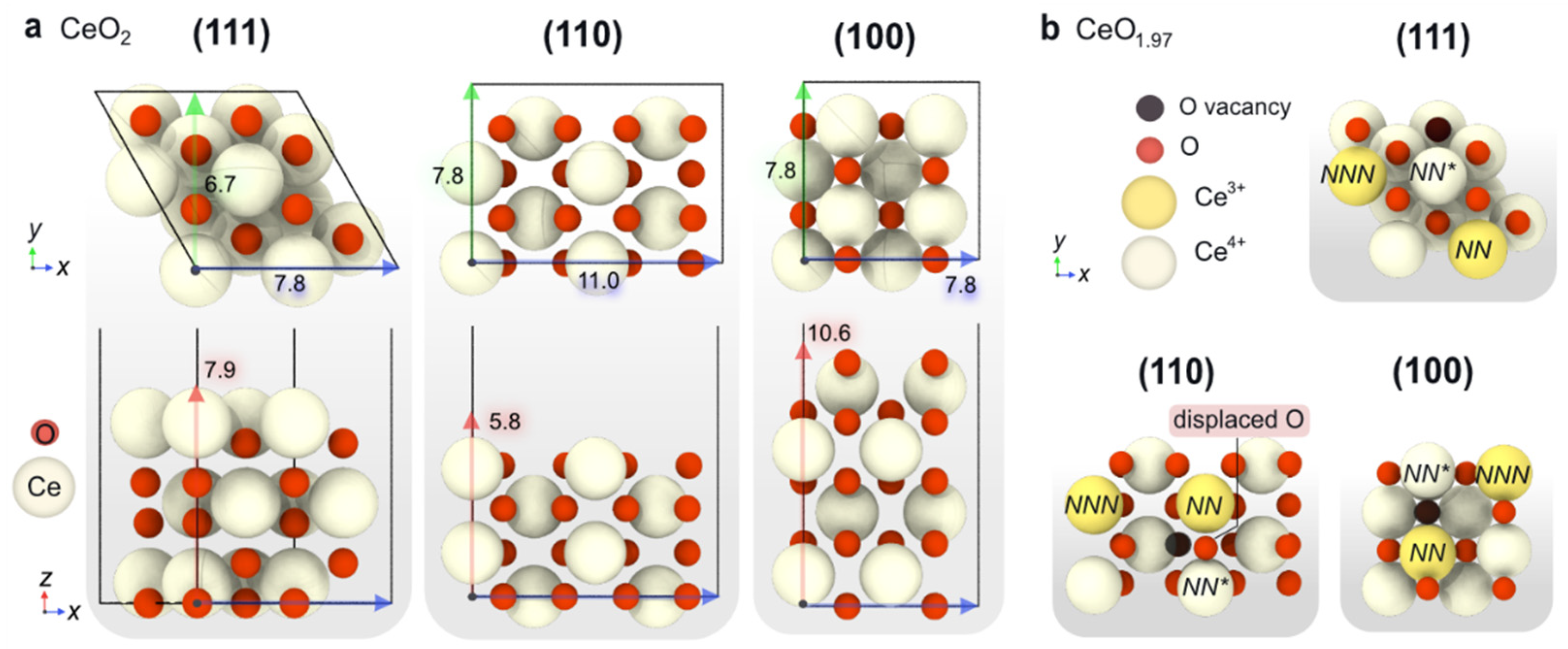

2.1.2. Computational Simulation of Low-Index Ceria Surfaces

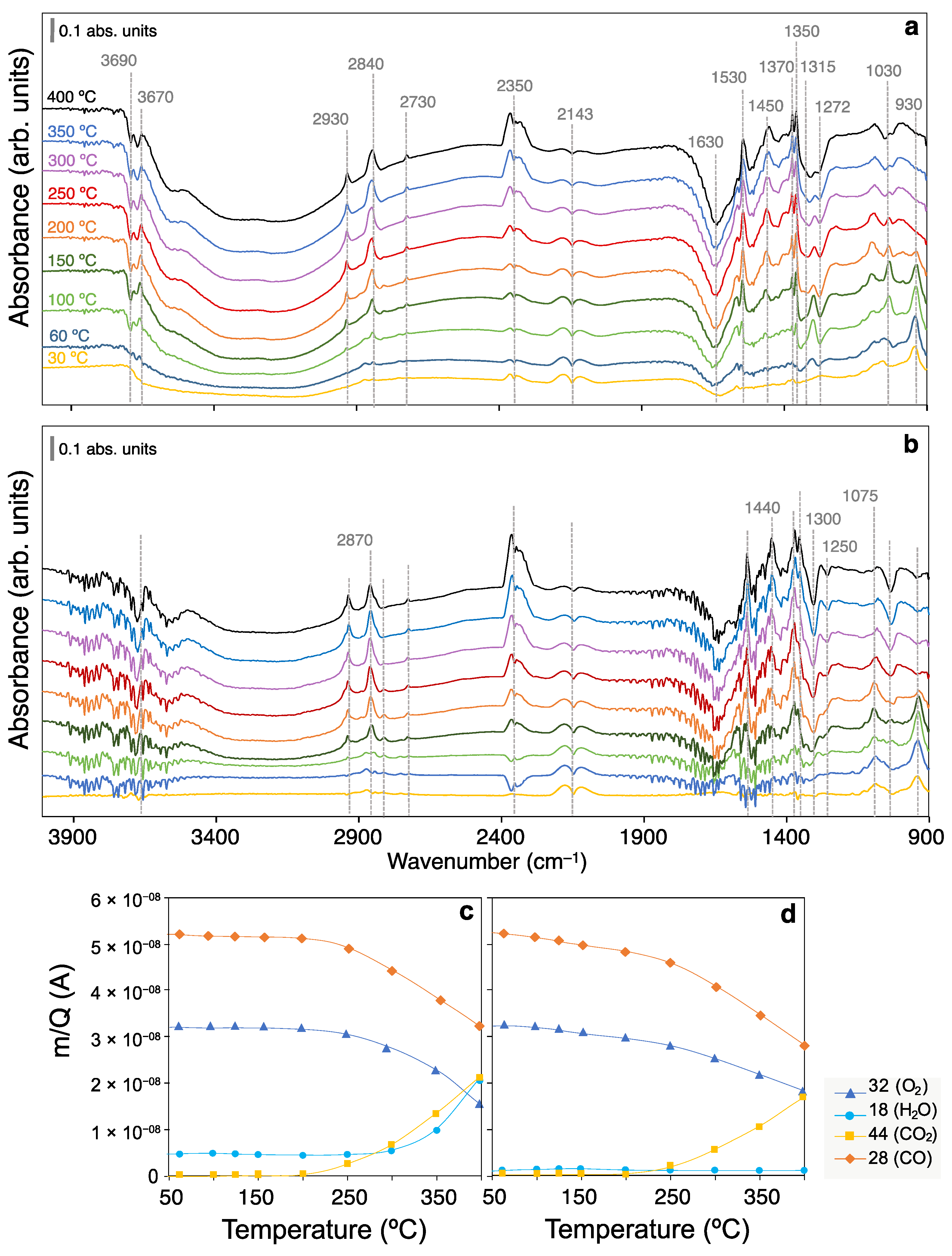

2.2. CO Oxidation Operando DRIFTS Experiments

2.3. DFT Simulation of CO-PROX Reaction in Ceria Catalysts

2.3.1. Surface Coverage Studies in CO-PROX Conditions

2.3.2. CO Oxidation on CeO2 in CO-PROX Atmosphere

- CeO2(111) clean surface

- 2 OH-covered CeO2(111) surface

- CeO2(110) surface

- CeO2(100) surface

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis of Nano-Shaped Ceria Samples

4.2. Physicochemical Characterization of the Materials

4.3. CO oxidation Operando DRIFTS Experiments

4.4. DFT Calculations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dey, S.; Dhal, G.C. Cerium catalysts applications in carbon monoxide oxidations. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2020, 3, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Grinter, D.C.; Liu, Z.; Palomino, R.M.; Senanayake, S.D. Ceria-based model catalysts: Fundamental studies on the importance of the metal–ceria interface in CO oxidation, the water–gas shift, CO2 hydrogenation, and methane and alcohol reforming. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1824–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Rothenberg, G. Sustainable selective oxidations using ceria-based materials. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Başar, M.S.; Çağlayan, B.S.; Aksoylu, A.E. A study on catalytic hydrogen production: Thermodynamic and experimental analysis of serial OSR-PROX system. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 178, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio-Fraccari, E.; Abele, A.; Zitta, N.; Francesconi, J.; Mariño, F. CO removal for hydrogen purification via Water Gas Shift and COPROX reactions with monolithic catalysts. Fuel 2021, 122419, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrauto, R.; Hwang, S.; Shore, L.; Ruettinger, W.; Lampert, J.; Giroux, T.; Liu, Y.; Ilinich, O. Generating Hydrogen for the PEM Fuel Cell. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2003, 33, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, B.; Hafttananian, M.; Khamani, S.; Ramiar, A.; Ranjbar, A.A. Poisoning of proton exchange membrane fuel cells by contaminants and impurities: Review of mechanisms, effects, and mitigation strategies. J. Power Source 2019, 427, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molochas, C.; Tsiakaras, P. Carbon Monoxide Tolerant Pt-Based Electrocatalysts for H2-PEMFC Applications: Current Progress and Challenges. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Izumi, Y. Recent Advances in the Preferential Thermal-/Photo-Oxidation of Carbon Monoxide: Noble Versus Inexpensive Metals and Their Reaction Mechanisms. Catal. Surv. Asia 2016, 20, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarra, D.; Cámara, A.L.; Monte, M.; Rasmussen, S.B.; Chinchilla, L.E.; Hungría, A.B.; Munuera, G.; Gyorffy, N.; Schay, Z.; Corberán, V.C.; et al. Preferential oxidation of CO in excess H2 over CuO/CeO2 catalysts: Characterization and performance as a function of the exposed face present in the CeO2 support. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 130–131, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polster, C.S.; Nair, H.; Baertsch, C.D. Study of active sites and mechanism responsible for highly selective CO oxidation in H2 rich atmospheres on a mixed Cu and Ce oxide catalyst. J. Catal. 2009, 266, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Miller, J.T.; Baertsch, C.D. Identifying the active redox oxygen sites in a mixed Cu and Ce oxide catalyst by in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy and anaerobic reactions with CO in concentrated H2. J. Catal. 2012, 294, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Arias, A.; Gamarra, D.; Fernández-García, M.; Hornés, A.; Belver, C. Spectroscopic Study on the Nature of Active Entities in Copper–Ceria CO-PROX Catalysts. Top. Catal. 2009, 52, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Deo, S.; Dooley, K.; Janik, M.J.; Rioux, R.M. Influence of metal nuclearity and physicochemical properties of ceria on the oxidation of carbon monoxide. Chin. J. Catal. 2020, 41, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konsolakis, M.; Lykaki, M. Recent Advances on the Rational Design of Non-Precious Metal Oxide Catalysts Exemplified by CuOx/CeO2 Binary System: Implications of Size, Shape and Electronic Effects on Intrinsic Reactivity and Metal-Support Interactions. Catalysts 2020, 10, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qiu, Z.; Guo, X.; Mao, J.; Zhou, R. New Design and Construction of Abundant Active Surface Interfacial Copper Entities in CuxCe1–xO2 Nanorod Catalysts for CO-PROX. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 9178–9189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, M.J. Removal of Trace Contaminants from Fuel Processing Reformate: Preferential Oxidation (Prox). In Hydrogen and Syngas Production and Purification Technologies; Liu, K., Song, C., Subramani, V., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 329–356. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Haddadin, T.; Rubiano, D.P.; Nair, H.; Polster, C.S.; Baertsch, C.D. Quantification of Reactive CO and H2 on CuOx-CeO2 during CO Preferential Oxidation by Reactive Titration and Steady State Isotopic Transient Kinetic Analysis. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Arias, A.; Hungría, A.B.; Munuera, G.; Gamarra, D. Preferential oxidation of CO in rich H2 over CuO/CeO2: Details of selectivity and deactivation under the reactant stream. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2006, 65, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedmak, G.; Hočevar, S.; Levec, J. Kinetics of selective CO oxidation in excess of H2 over the nanostructured Cu0.1Ce0.9O2−y catalyst. J. Catal. 2003, 213, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polster, C.S.; Baertsch, C.D. Application of CuOx–CeO2catalysts as selective sensor substrates for detection of CO in H2 fuel. Chem. Commun. 2008, 34, 4046–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yan, L.; Song, W.; Xu, D. Kinetic interplay between hydrogen and carbon monoxide in syngas-fueled catalytic micro-combustors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 12681–12695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snytnikov, P.V.; Popova, M.M.; Men, Y.; Rebrov, E.V.; Kolb, G.; Hessel, V.; Schouten, J.C.; Sobyanin, V.A. Preferential CO oxidation over a copper–cerium oxide catalyst in a microchannel reactor. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2008, 350, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.; Kim, D.H. Kinetics of CO and H2 oxidation over CuO-CeO2 catalyst in H2 mixtures with CO2 and H2O. Catal. Today 2008, 132, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayastuy, J.L.; Gurbani, A.; González-Marcos, M.P.; Gutiérrez-Ortiz, M.A. Kinetics of Carbon Monoxide Oxidation over CuO Supported on Nanosized CeO2. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 5633–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, Z.; Lin, W. DRIFTS study of Cu–Zr–Ce–O catalysts for selective CO oxidation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 9324–9333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, N.; Meemken, F.; Baiker, A. Insight into the mechanism of the preferential oxidation of carbon monoxide by using isotope-modulated excitation IR spectroscopy. ChemCatChem 2013, 5, 2199–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, G.; Williams, L.; Graham, U.; Thomas, G.A.; Sparks, D.E.; Davis, B.H. Low temperature water–gas shift: In situ DRIFTS-reaction study of ceria surface area on the evolution of formates on Pt/CeO2 fuel processing catalysts for fuel cell applications. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2003, 252, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkwitz, Y.; Karpenko, A.; Plzak, V.; Leppelt, R.; Schumacher, B.; Behm, R.J. Influence of CO2 and H2 on the low-temperature water–gas shift reaction on Au/CeO2 catalysts in idealized and realistic reformate. J. Catal. 2007, 246, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davó-Quiñonero, A.; Navlani-García, M.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; Bueno-López, A.; Anderson, J.A. Role of Hydroxyl Groups in the Preferential Oxidation of CO over Copper Oxide-Cerium Oxide Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Benedetto, A.; Landi, G.; Lisi, L. CO reactive adsorption at low temperature over CuO/CeO2 structured catalytic monolith. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 12262–12275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornés, A.; Bera, P.; Cámara, A.L.; Gamarra, D.; Munuera, G.; Martínez-Arias, A. CO-TPR-DRIFTS-MS in situ study of CuO/Ce1−xTbxO2−y (x=0, 0.2 and 0.5) catalysts: Support effects on redox properties and CO oxidation catalysis. J. Catal. 2009, 268, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, T.; Lisi, L.; Pirone, R.; Russo, G. On the role of redox properties of CuO/CeO2 catalysts in the preferential oxidation of CO in H2-rich gases. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2008, 348, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkarev, V.V.; Kovalchuk, V.I.; d’Itri, J.L. Probing Defect Sites on the CeO2 Surface with Dioxygen. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 5341–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Lu, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Luo, M. UV and Visible Raman Studies of Oxygen Vacancies in Rare-Earth-Doped Ceria. Langmuir 2011, 27, 3872–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, W.H.; Hass, K.C.; McBride, J.R. Raman study of CeO2: Second-order scattering, lattice dynamics, and particle-size effects. Phys. Rev. B. Condens. Matter 1993, 48, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, C.; Hofmann, A.; Hess, C.; Ganduglia-Pirovano, M.V. Raman Spectra of Polycrystalline CeO2: A Density Functional Theory Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 20834–20849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainbayev, N.; Sriubas, M.; Virbukas, D.; Rutkuniene, Z.; Bockute, K.; Bolegenova, S.; Laukaitis, G. Raman study of nanocrystalline-doped ceria oxide thin films. Coatings 2020, 10, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Ferrer, C.; Parres-Esclapez, S.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; Bueno-López, A. Relationship between surface area and crystal size of pure and doped cerium oxides. J. Rare Earths 2010, 28, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, M.; Howe, J.; Meyer, H.M.; Overbury, S.H. Probing Defect Sites on CeO2 Nanocrystals with Well-Defined Surface Planes by Raman Spectroscopy and O2 Adsorption. Langmuir 2010, 26, 16595–16606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wen, J.; Poeppelmeier, K.R.; Marks, L.D. Imaging the Atomic Surface Structures of CeO2 Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.; Patil, S.; Kuchibhatla, S.V.N.T.; Seal, S. Size dependency variation in lattice parameter and valency states in nanocrystalline cerium oxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 87, 133113–133116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovarelli, A.; Llorca, J. Ceria Catalysts at Nanoscale: How Do Crystal Shapes Shape Catalysis? ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 4716–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Luo, T.; Meng, X.; Wu, H.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Ji, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, C.; Zhan, Z. Shape-Dependent Activity of Ceria for Hydrogen Electro-Oxidation in Reduced-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Small 2015, 11, 5581–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowell, S.; Shields, J.E.; Thomas, M.A.; Thommes, M. Characterization of Porous Solids and Powders: Surface Area, Pore Size and Density. In Particle Technology Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 16, ISSN 1567-827X. [Google Scholar]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Mayyas, M.; Koshy, P.; Hart, J.N.; Sorrell, C.C. Growth mechanism of ceria nanorods by precipitation at room temperature and morphology-dependent photocatalytic performance. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 4766–4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, M.; Grigoleit, S.; Sayle, D.C.; Parker, S.C.; Watson, G.W. Density functional theory studies of the structure and electronic structure of pure and defective low index surfaces of ceria. Surf. Sci. 2005, 576, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montini, T.; Melchionna, M.; Monai, M.; Fornasiero, P. Fundamentals and Catalytic Applications of CeO2-Based Materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5987–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doornkamp, C.; Ponec, V. The universal character of the Mars and Van Krevelen mechanism. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2000, 162, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdevila-Cortada, M.; Vilé, G.; Teschner, D.; Pérez-Ramírez, J.; López, N. Reactivity descriptors for ceria in catalysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 197, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, M.; Cai, L.; Bajdich, M.; García-Melchor, M.; Li, H.; He, J.; Wilcox, J.; Wu, W.; Vojvodic, A.; Zheng, X. Enhancing Catalytic CO Oxidation over Co3O4 Nanowires by Substituting Co2+ with Cu2+. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 4485–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farra, R.; García-Melchor, M.; Eichelbaum, M.; Hashagen, M.; Frandsen, W.; Allan, J.; Girgsdies, F.; Szentmiklósi, L.; López, N.; Teschner, D. Promoted Ceria: A Structural, Catalytic, and Computational Study. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 2256–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropp, T.; Mavrikakis, M. Brønsted–Evans–Polanyi relation for CO oxidation on metal oxides following the Mars–van Krevelen mechanism. J. Catal. 2019, 377, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganduglia-Pirovano, M.V.; Da Silva, J.L.F.; Sauer, J. Density-Functional Calculations of the Structure of Near-Surface Oxygen Vacancies and Electron Localization on CeO2(111). Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 26101–26105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Teng, B.-T.; Wen, X.-D.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q.-P.; Zhao, L.-H.; Luo, M.-F. Superoxide and Peroxide Species on CeO2(111), and Their Oxidation Roles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 15986–15991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Fabris, S. Role of surface peroxo and superoxo species in the low-temperature oxygen buffering of ceria: Density functional theory calculations. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 81404–81408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.M.; Abernathy, H.; Chen, H.-T.; Lin, M.C.; Liu, M. Characterization of O2–CeO2 Interactions Using In Situ Raman Spectroscopy and First-Principle Calculations. ChemPhysChem 2006, 7, 1957–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, M. Healing of oxygen vacancies on reduced surfaces of gold-doped ceria. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 144702–144711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ziemba, M.; Schilling, C.; Ganduglia-Pirovano, M.V.; Hess, C. Toward an Atomic-Level Understanding of Ceria-Based Catalysts: When Experiment and Theory Go Hand in Hand. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 2884–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Han, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, F.; Xue, W. Highly Reducible Nanostructured CeO2 for CO Oxidation. Catalysts 2018, 8, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Rovira, L.; Sánchez-Amaya, J.M.; López-Haro, M.; del Rio, E.; Hungría, A.B.; Midgley, P.; Calvino, J.J.; Bernal, S.; Botana, F.J. Single-Step Process To Prepare CeO2 Nanotubes with Improved Catalytic Activity. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hou, F.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Chen, D.; Yang, Y. A facile synthesis for cauliflower like CeO2 catalysts from Ce-BTC precursor and their catalytic performance for CO oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 423, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, R.; Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. Shape and crystal-plane effects of nanoscale ceria on the activity of Au-CeO2 catalysts for the water-gas shift reaction. Angew. Chemie-Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2884–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiivanov, K. Chapter Two—Identification and Characterization of Surface Hydroxyl Groups by Infrared Spectroscopy; Jentoft, F.C., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Volume 57, pp. 99–318. ISBN 0360-0564. [Google Scholar]

- Saw, E.T.; Oemar, U.; Ang, M.L.; Kus, H.; Kawi, S. High-temperature water gas shift reaction on Ni-Cu/CeO2 catalysts: Effect of ceria nanocrystal size on carboxylate formation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 5336–5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kottwitz, M.; Vincent, J.L.; Enright, M.J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Senanayake, S.D.; Yang, W.-C.D.; Crozier, P.A.; et al. Dynamic structure of active sites in ceria-supported Pt catalysts for the water gas shift reaction. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Ma, Y.; Ding, L.; Xu, L.; Wu, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Huang, W. Reactivity of Hydroxyls and Water on a CeO2(111) Thin Film Surface: The Role of Oxygen Vacancy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 5800–5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammert, J.; Moon, J.; Wu, Z. A review of the interactions between ceria and H2 and the applications to selective hydrogenation of alkynes. Chin. J. Catal. 2020, 41, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Melchor, M.; López, N. Homolytic Products from Heterolytic Paths in H2 Dissociation on Metal Oxides: The Example of CeO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 10921–10926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández-Torre, D.; Carrasco, J.; Ganduglia-Pirovano, M.V.; Pérez, R. Hydrogen activation, diffusion, and clustering on CeO2(111): A DFT+U study. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 141, 14703–14712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Z.; Woo, T.K.; Hermansson, K. Strong and weak adsorption of CO on CeO2 surfaces from first principles calculations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 396, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, M.; Watson, G.W. The Surface Dependence of CO Adsorption on Ceria. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 16600–16606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudiyanselage, K.; Kim, H.Y.; Senanayake, S.D.; Baber, A.E.; Liu, P.; Stacchiola, D. Probing adsorption sites for CO on ceria. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 15856–15862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Fabris, S. CO Adsorption and Oxidation on Ceria Surfaces from DFT+U Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 8643–8648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, M.; Wu, Z. In situ spectroscopic insights into the redox and acid-base properties of ceria catalysts. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 2122–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Mann, A.K.P.; Li, M.; Overbury, S.H. Spectroscopic Investigation of Surface-Dependent Acid–Base Property of Ceria Nanoshapes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 7340–7350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; Hu, P.; Gong, X.Q.; Lu, G. A DFT+U study of the lattice oxygen reactivity toward direct CO oxidation on the CeO2(111) and (110) surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 16573–16580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Cao, T.; Gao, Y.; Li, D.; Xiong, F.; Huang, W. Probing Surface Structures of CeO2, TiO2, and Cu2O Nanocrystals with CO and CO2 Chemisorption. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 21472–21485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rodríguez, S.; Davó-Quiñonero, A.; Bailón-García, E.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; Herrera, F.C.; Pellegrin, E.; Escudero, C.; García-Melchor, M.; Bueno-López, A. Elucidating the Role of the Metal Catalyst and Oxide Support in the Ru/CeO2-Catalyzed CO2 Methanation Mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 25533–25544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneggi, E.; Wiater, D.; de Leitenburg, C.; Llorca, J.; Trovarelli, A. Shape-Dependent Activity of Ceria in Soot Combustion. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, H.-X.; Sun, L.-D.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Si, R.; Feng, W.; Zhang, H.-P.; Liu, H.-C.; Yan, C.-H. Shape-Selective Synthesis and Oxygen Storage Behavior of Ceria Nanopolyhedra, Nanorods, and Nanocubes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 24380–24385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dudarev, S.L.; Botton, G.A.; Savrasov, S.Y.; Humphreys, C.J.; Sutton, A.P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 57, 1505–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | F2g (cm−1) | D/F2g Band Ratio | SBET (m2/g) | Vmicro (cc/g) | a (nm) | D (nm) | Surface Ce3+ (%) | Olab/Olat (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polycrystalline | 462.6 | 0.05 | 71 | 0.04 | 5.411 | 9.5 | 21 | 30 |

| Nanocubes | 464.6 | 0.05 | 30 | 0.00 | 5.414 | 22.5 | 26 | 35 |

| Nanorods | 462.6 | 0.06 | 93 | 0.06 | 5.411 | 9.0 | 21 | 19 |

| Surface | Formula | γ (eV/Å2) | Evac (eV/O Atom) | e– Distr. | Eads O2 (eV) | Type *O2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CeO2(111) | Ce12O24 | 0.044 | 2.22 | NN/NNN | 0.79 | O2− |

| 2.71 | NN/NN | 0.36 | O22− | |||

| CeO2(110) | Ce16O32 | 0.075 | 1.32 | NN/NNN | 0.72 | O2– |

| 1.80 | NN/NN | 0.17 | O22– | |||

| CeO2(100) | Ce16O32 | 0.113 | 1.68 | NN/NNN | 0.26 | O2– |

| 1.76 | NN/NN | −0.34 | O22– |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davó-Quiñonero, A.; López-Rodríguez, S.; Chaparro-Garnica, C.; Martín-García, I.; Bailón-García, E.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; Bueno-López, A.; García-Melchor, M. Investigations of the Effect of H2 in CO Oxidation over Ceria Catalysts. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1556. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11121556

Davó-Quiñonero A, López-Rodríguez S, Chaparro-Garnica C, Martín-García I, Bailón-García E, Lozano-Castelló D, Bueno-López A, García-Melchor M. Investigations of the Effect of H2 in CO Oxidation over Ceria Catalysts. Catalysts. 2021; 11(12):1556. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11121556

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavó-Quiñonero, Arantxa, Sergio López-Rodríguez, Cristian Chaparro-Garnica, Iris Martín-García, Esther Bailón-García, Dolores Lozano-Castelló, Agustín Bueno-López, and Max García-Melchor. 2021. "Investigations of the Effect of H2 in CO Oxidation over Ceria Catalysts" Catalysts 11, no. 12: 1556. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11121556

APA StyleDavó-Quiñonero, A., López-Rodríguez, S., Chaparro-Garnica, C., Martín-García, I., Bailón-García, E., Lozano-Castelló, D., Bueno-López, A., & García-Melchor, M. (2021). Investigations of the Effect of H2 in CO Oxidation over Ceria Catalysts. Catalysts, 11(12), 1556. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11121556