Gender Differences in the Response to Decision Power and Responsibility—Framing Effects in a Dictator Game

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

3. Experimental Design and Procedures

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Supplementary Tables and Figures

| Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Responsibility | DecisionPower | |

| male | 0.42 (a) | 0.55 | 0.49 |

| age | 21.79 | 21.55 | 20.88 |

| N | 56 | 77 | 74 |

| Variables | Give |

|---|---|

| Responsibility | −0.004 |

| (0.041) | |

| DecisionPower | 0.066 |

| (0.041) | |

| Responsibility × male | 0.128 ** |

| (0.061) | |

| DecisionPower × male | −0.066 |

| (0.061) | |

| male | −0.050 |

| (0.047) | |

| age | −0.002 |

| (0.004) | |

| Constant | 0.419 *** |

| (0.098) | |

| Observations | 205 |

| R-squared | 0.155 |

Appendix B. Instructions for Participants of the Experiment

- the instructions.

- a small envelope with the number 1 on it.

- a small envelope with the number 2 on it.

- Please do not open the two small envelopes yet.

- Please read the instructions carefully and follow the instructions.

- Please stay quietly in your seat for the entire duration of the experiment and do not talk to other participants.

- Please refrain from using your cell phone during the experiment.

- Please do not look at other participants’ sheets and do not let other participants look at yours.

- Please keep your place card until the end of the lecture. Only with this place card, you are able to receive a payment.

- After this lecture, the participants who have been chosen by the throw of the die for payment will receive their payment. The amount paid out depends on the individual decisions by the participants.

- Please keep your place card until the end of the lecture because only with the place card, you are able to receive a payment.

- You are a participant A. The participants B are in another room in this building at this very moment.

- You decide on how much of your endowment of 30 Euros you want to give to the participant B you are matched to (if your payoff-number should be chosen by the throw of the die).

- You will receive your payment at the end of the lecture for handing in your place card (if your payoff-number should be chosen by the throw of the die).

- Open the envelope with the number 1 and note your decision on the inlying decision sheet.

- Fold the decision sheet and put it back into the envelope number 1.

- Open the envelope with the number 2 and fill in the inlying questionnaire.

- Fold the questionnaire and put it back into the envelope number 2.

- Put envelope number 1, envelope number 2 and the instructions into the large envelope and seal it.

- Please wait quietly until all other participants are finished and all envelopes have been collected.

Appendix C. Pictures of the Material Used for the Experiment

References

- Kahneman, D.; Knetsch, J.L.; Thaler, R.H. Fairness and the Assumptions of Economics. J. Bus. 1986, 59, S285–S300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, R.; Horowitz, J.L.; Savin, N.E.; Sefton, M. Fairness in Simple Bargaining Experiments. Games Econ. Behav. 1994, 6, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C. Dictator games: A meta study. Exp. Econ. 2011, 14, 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. Chapter 8: The Economics of Fairness, Reciprocity and Altruism—Experimental Evidence and New Theories. In Handbook of the Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity: Foundations; Kolm, S.C., Ythier, J.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 615–691. [Google Scholar]

- Krupka, E.L.; Weber, R.A. Identifying Social Norms Using Coordination Games: Why Does Dictator Game Sharing Vary? J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2013, 11, 495–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, J.A. On the Interpretation of Giving in Dictator Games. J. Polit. Econ. 2007, 115, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, S.D.; List, J.A. What Do Laboratory Experiments Measuring Social Preferences Reveal About the Real World? J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizzo, D.J. Experimenter demand effects in economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 2010, 13, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, P.; Jaeger, B. Another frame, another game? Explaining framing effects in economic games. In Proceedings of the Second International Workshop on Norms, Actions, Games, Toulouse, France, 20–21 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brañas-Garza, P.; Durán, M.A.; Paz Espinosa, M. The Role of Personal Involvement and Responsibility in Unfair Outcomes: A Classroom Investigation. Ration. Soc. 2009, 21, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, J.; Weber, R.A.; Kuang, J.X. Exploiting moral wiggle room: experiments demonstrating an illusory preference for fairness. Econ. Theory 2007, 33, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etang, A.; Fielding, D.; Knowles, S. Who votes expressively, and why? Experimental evidence. Bull. Econ. Res. 2016, 68, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazar, N.; Amir, O.; Ariely, D. The Dishonesty of Honest People: A Theory of Self-Concept Maintenance. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, T.; Johannesson, M. Anticipated verbal feedback induces altruistic behavior. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2008, 29, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, E.; Houser, D. Avoiding the sharp tongue: Anticipated written messages promote fair economic exchange. J. Econ. Psychol. 2009, 30, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, E.; Tcherkassof, A.; Gassmann, X. Sincere Giving and Shame in a Dictator Game; Groupe de Recherche en Economie Théorique et Appliquée: Bordeaux, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Croson, R.; Gneezy, U. Gender Differences in Preferences. J. Econ. Lit. 2009, 47, 448–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, T.; Johannesson, M.; Mollerstrom, J.; Munkhammar, S. Gender differences in social framing effects. Econ. Lett. 2013, 118, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, A.; Hottes, J.; Davis, W.L. Cooperation and optimal responding in the Prisoner’s Dilemma game: Effects of sex and physical attractiveness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 17, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H. Gender and social influence: A social psychological analysis. Am. Psychol. 1983, 38, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaux, K.; Major, B. Putting gender into context: An interactive model of gender-related behavior. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcock, L.; Laschever, S. Women Don’t Ask: Negotiation and the Gender Divide; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H. The His and Hers of Prosocial Behavior: An Examination of the Social Psychology of Gender. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilman, M.E.; Chen, J.J. Same behavior, different consequences: Reactions to men’s and women’s altruistic citizenship behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, F.; Brañas-Garza, P.; Cobo-Reyes, R.; Jimenez, N.; Miller, L.M. Are women expected to be more generous? Exp. Econ. 2009, 12, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brañas-Garza, P.; Capraro, V.; Rascon, E. Gender Differences in Altruism on Mechanical Turk: Expectations and Actual Behaviour. 2018. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2796221 (accessed on 12 April 2018).

- De Wit, A.; Bekkers, R. Exploring Gender Differences in Charitable Giving: The Dutch Case. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2016, 45, 741–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brañas-Garza, P. Promoting helping behavior with framing in dictator games. J. Econ. Psychol. 2007, 28, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, V.; Jagfeld, G.; Klein, R.; Mul, M.; van de Pol, I. What’s the Right Thing to Do? Increasing Pro-Sociality with Simple Moral Nudges. 2017. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3064004 (accessed on 12 April 2018).

- Haley, K.J.; Fessler, D.M. Nobody’s watching? Subtle cues affect generosity in an anonymous economic game. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2005, 26, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, M.; Ishii, K.; Watabe, M.; Kitayama, S. Minimal social cues in the dictator game. J. Econ. Psychol. 2009, 30, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J.; Rao, J.M. The power of asking: How communication affects selfishness, empathy, and altruism. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruttel, L.; Stolley, F.; Utikal, V. Getting a Yes. An Experiment on the Power of Asking; The Munich Personal RePEc Archive (MPRA): Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Charness, G.; Rabin, M. Expressed preferences and behavior in experimental games. Games Econ. Behav. 2005, 53, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohlin, E.; Johannesson, M. Communication: Content or relationship? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 65, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bó, E.; Dal Bó, P. ’Do the right thing:’ The effects of moral suasion on cooperation. J. Public Econ. 2014, 117, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E.; McCabe, K.; Shachat, K.; Smith, V. Preferences, Property Rights, and Anonymity in Bargaining Games. Games Econ. Behav. 1994, 7, 346–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E.; McCabe, K.; Smith, V.L. Social Distance and Other-Regarding Behavior in Dictator Games. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 653–660. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, T.L.; Frykblom, P.; Shogren, J.F. Hardnose the Dictator. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1218–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, A.; Pointner, S. Anonymity in the dictator game revisited. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 81, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufwenberg, M.; Muren, A. Generosity, anonymity, gender. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2006, 61, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnet, I.; Frey, B.S. The sound of silence in prisoner’s dilemma and dictator games. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1999, 38, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, D.A.; Loewenstein, G. Helping a Victim or Helping the Victim: Altruism and Identifiability. J. Risk Uncertain. 2003, 26, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeree, J.K.; McConnell, M.A.; Mitchell, T.; Tromp, T.; Yariv, L. The 1/d Law of Giving. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2010, 2, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Gneezy, U. What’s in a name? Anonymity and social distance in dictator and ultimatum games. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 68, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, C.C.; Grossman, P.J. Altruism in Anonymous Dictator Games. Games Econ. Behav. 1996, 16, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.M. Evidence from an Experiment on Charity to Welfare Recipients: Reciprocity, Altruism and the Empathic Responsiveness Hypothesis. Econ. J. 2007, 117, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardsley, N. Dictator game giving: Altruism or artefact? Exp. Econ. 2008, 11, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Chakravarty, S. The effect of minimal group framing in a dictator game experiment. 2012. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2071006 (accessed on 12 April 2018).

- Dreber, A.; Ellingsen, T.; Johannesson, M.; Rand, D.G. Do people care about social context? Framing effects in dictator games. Exp. Econ. 2013, 16, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvoy, R. The Effects of Give and Take Framing in a Dictator Game. Honors Thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, P.J.; Eckel, C.C. Giving versus taking for a cause. Econ. Lett. 2015, 132, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.C.; List, J.A.; Price, M.; Sadiraj, V.; Samek, A. Moral Costs and Rational Choice: Theory and Experimental Evidence; The National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenok, O.; Millner, E.L.; Razzolini, L. Taking, giving, and impure altruism in dictator games. Exp. Econ. 2014, 17, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenok, O.; Millner, E.; Razzolini, L. Feelings of ownership in dictator games. J. Econ. Psychol. 2017, 61, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J.; Vesterlund, L. Which is the Fair Sex? Gender Differences in Altruism. Q. J. Econ. 2001, 116, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ner, A.; Kong, F.; Putterman, L. Share and share alike? Gender-pairing, personality, and cognitive ability as determinants of giving. J. Econ. Psychol. 2004, 25, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erat, S.; Gneezy, U. White Lies. Manag. Sci. 2011, 58, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exadaktylos, F.; Espín, A.M.; Brañas-Garza, P. Experimental subjects are not different. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brañas-Garza, P.; Rodríguez-Lara, I.; Sánchez, A. Humans expect generosity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | The exact wording was: “You alone decide about the payoffs, and you are completely free in your decision”. |

| 2 | The exact wording was: “You bear the responsibility for both payoffs, your own and the one of participant B”. |

| 3 | See the theory of self-concept maintenance by Mazar et al. [13]. |

| 4 | These messages either reminded participants “that moral actions are those that treat others as you would like to be treated” or “that actions are moral to the extent that they contribute to maximizing collective payoffs”. |

| 5 | However, also paying the dictator in public can lead to lower generosity [41]. |

| 6 | 30 Euros ≈ 35 Dollars at the time of the experiment. |

| 7 | Only 10% of the participants were paid after the experiment took place as is explained in detail in the end of this Section. The instructions, however, stress that dictators should think carefully about their decision as it has real consequences if they are drawn for payment. Paying only a fraction of participants is not uncommon in experimental economics, especially in classroom settings [58] or in survey experiments [59]. |

| 8 | The original text in German was: “Sie tragen die Verantwortung für beide Auszahlungen, Ihre eigene und die von Teilnehmer/-in B”. |

| 9 | The original text in German was: “Sie allein entscheiden über die Auszahlungen, und Sie sind völlig frei in Ihrer Entscheidung”. |

| 10 | Prior to the experiment, we did a power calculation in which we estimated effect sizes by using the results from Brañas-Garza [28]. We concluded that we would need around 25 observations for each gender for each treatment to find significant effects. Thus, we intended to conduct the experiment with a minimum number of 150 dictators. |

| 11 | While it may potentially affect dictators’ decisions that receivers are not in the same room, we do not see a reason why such an effect should differ between the treatments. |

| 12 | Pictures of the material used for the experiment can be found in the Appendix C. |

| 13 | An English translation of the originally German verbal instructions, general instructions and specific instructions can be found in the Appendix B. |

| 14 | There were fewer participants in the second room than in the first room. Participants in the role of the dictator who sat in the first room received no information about the number of participants present in the second room. |

| 15 | For example, there are more men in the treatment Responsibility than in the treatment Control, who, on average, give slightly less than women. Hence, simply comparing the means may understate a potential effect. |

| 16 | A Tobit model may be more appropriate for the analysis of the dictators’ decision if left-censoring in the dependent variable is a concern. (See [60] or [3] for good discussions of the appropriateness of different models to analyze dictator game decisions.) However, only 7% of the dictators decided to give 0 Euro in our study, which is a very low fraction compared to other studies (A meta-analysis found 36% of dictators to give nothing to the recipient [3], while in a survey-experiment, which also paid only 1 in 10 participants, around 17% of dictators decided to give 0 Euro [59]). Therefore, we do not believe that censoring from below is an issue here and decided to use an OLS model due to the slightly easier interpretation of coefficients. Nevertheless, all of the results in Table 1 and Table A2 are robust to using a Tobit model. |

| 17 | Table A2 in the Appendix A additionally shows the results of an OLS regression including interaction effects of gender with the treatment variables. |

| 18 | Brañas-Garza [28] does not present results depending on gender. |

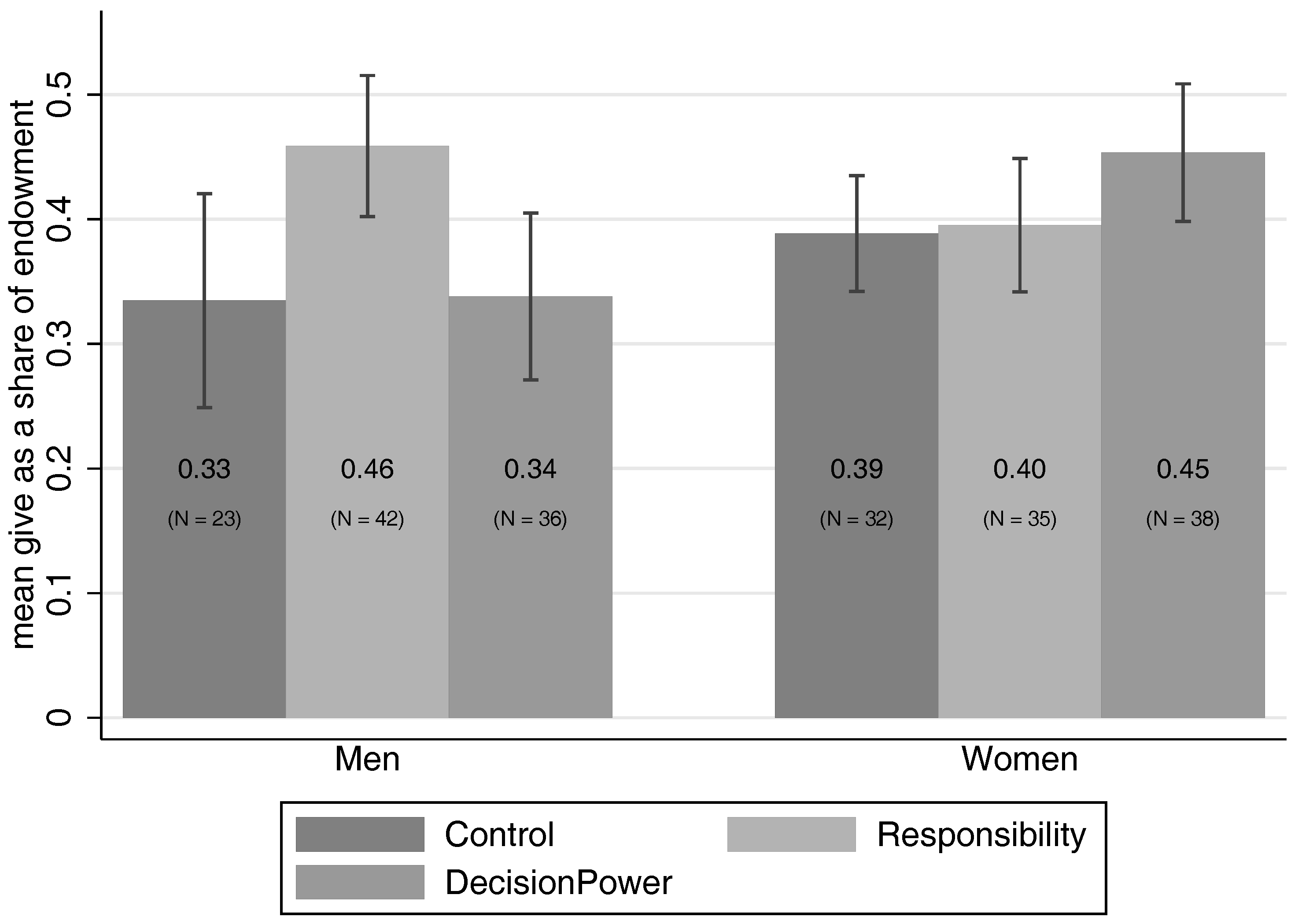

| Variables | (1) Full Sample | (2) Men | (3) Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responsibility | 0.063 ** | 0.125 ** | −0.002 |

| (0.031) | (0.050) | (0.037) | |

| DecisionPower | 0.030 | −0.003 | 0.068 * |

| (0.031) | (0.052) | (0.037) | |

| male | −0.028 | ||

| (0.025) | |||

| age | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.001 |

| (0.004) | (0.008) | (0.005) | |

| Constant | 0.429 *** | 0.418 ** | 0.402 *** |

| (0.099) | (0.189) | (0.106) | |

| Observations | 205 | 100 | 105 |

| R-squared | 0.100 | 0.171 | 0.136 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bruttel, L.; Stolley, F. Gender Differences in the Response to Decision Power and Responsibility—Framing Effects in a Dictator Game. Games 2018, 9, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020028

Bruttel L, Stolley F. Gender Differences in the Response to Decision Power and Responsibility—Framing Effects in a Dictator Game. Games. 2018; 9(2):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020028

Chicago/Turabian StyleBruttel, Lisa, and Florian Stolley. 2018. "Gender Differences in the Response to Decision Power and Responsibility—Framing Effects in a Dictator Game" Games 9, no. 2: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020028

APA StyleBruttel, L., & Stolley, F. (2018). Gender Differences in the Response to Decision Power and Responsibility—Framing Effects in a Dictator Game. Games, 9(2), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020028