Theory of Mind and General Intelligence in Dictator and Ultimatum Games

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

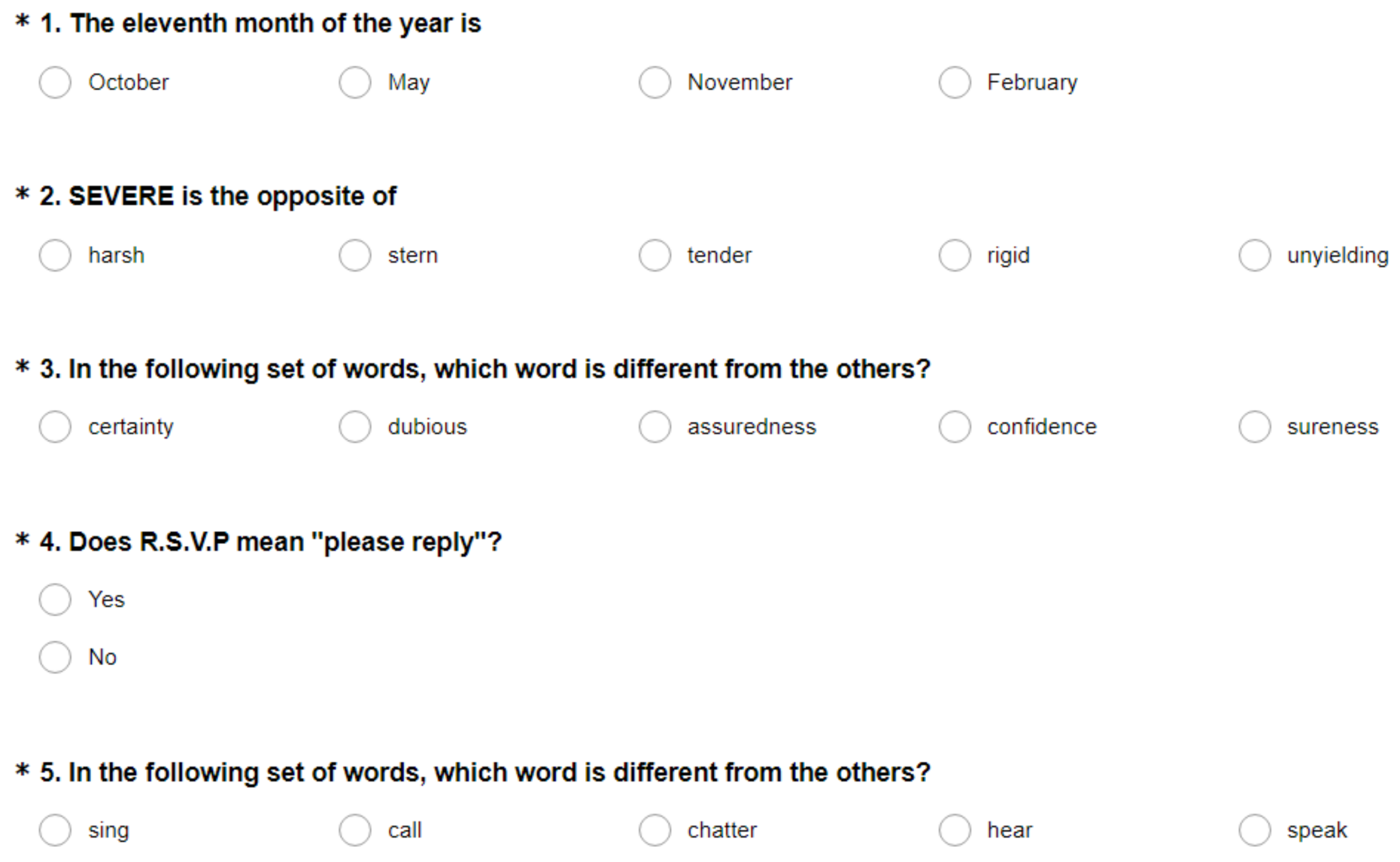

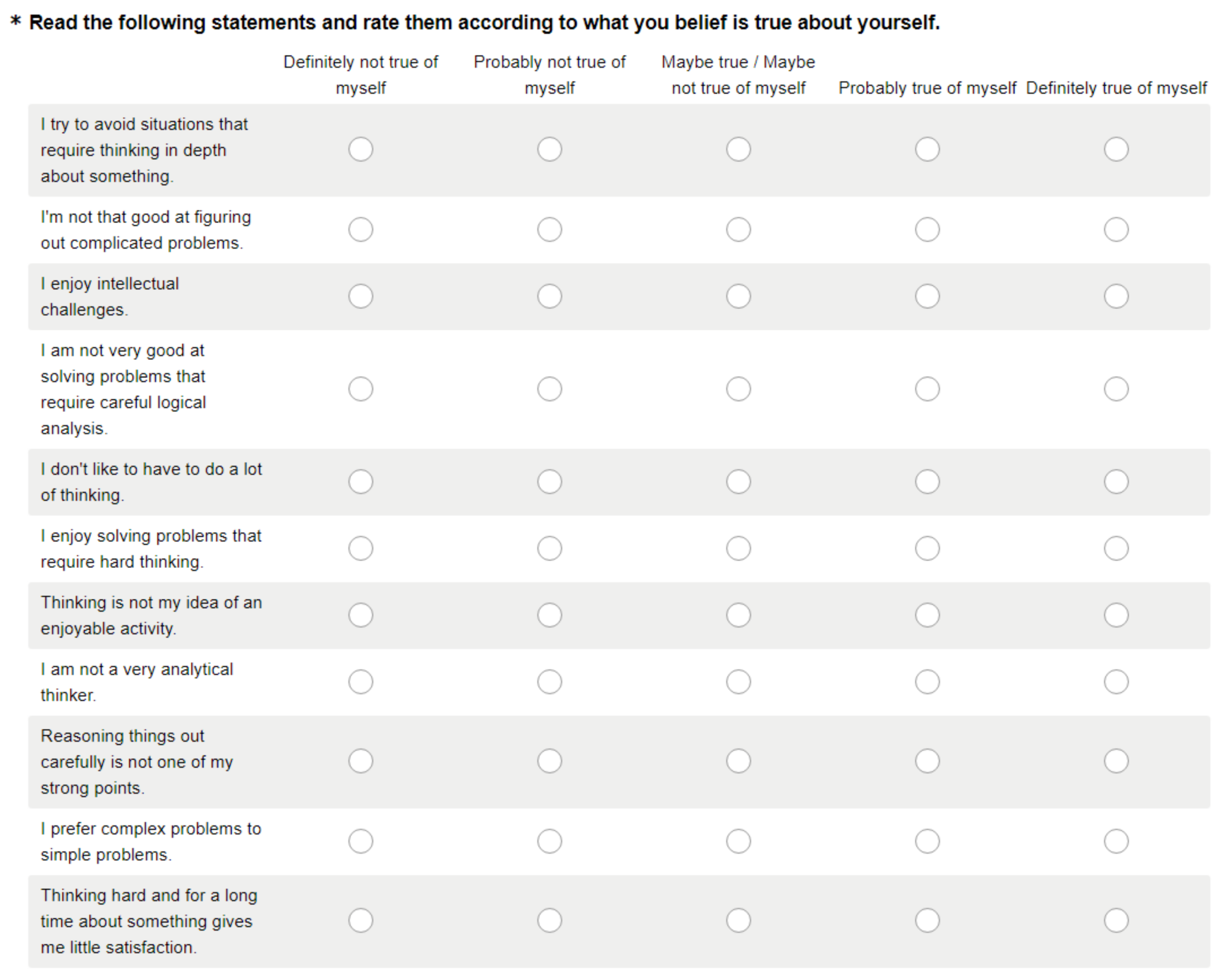

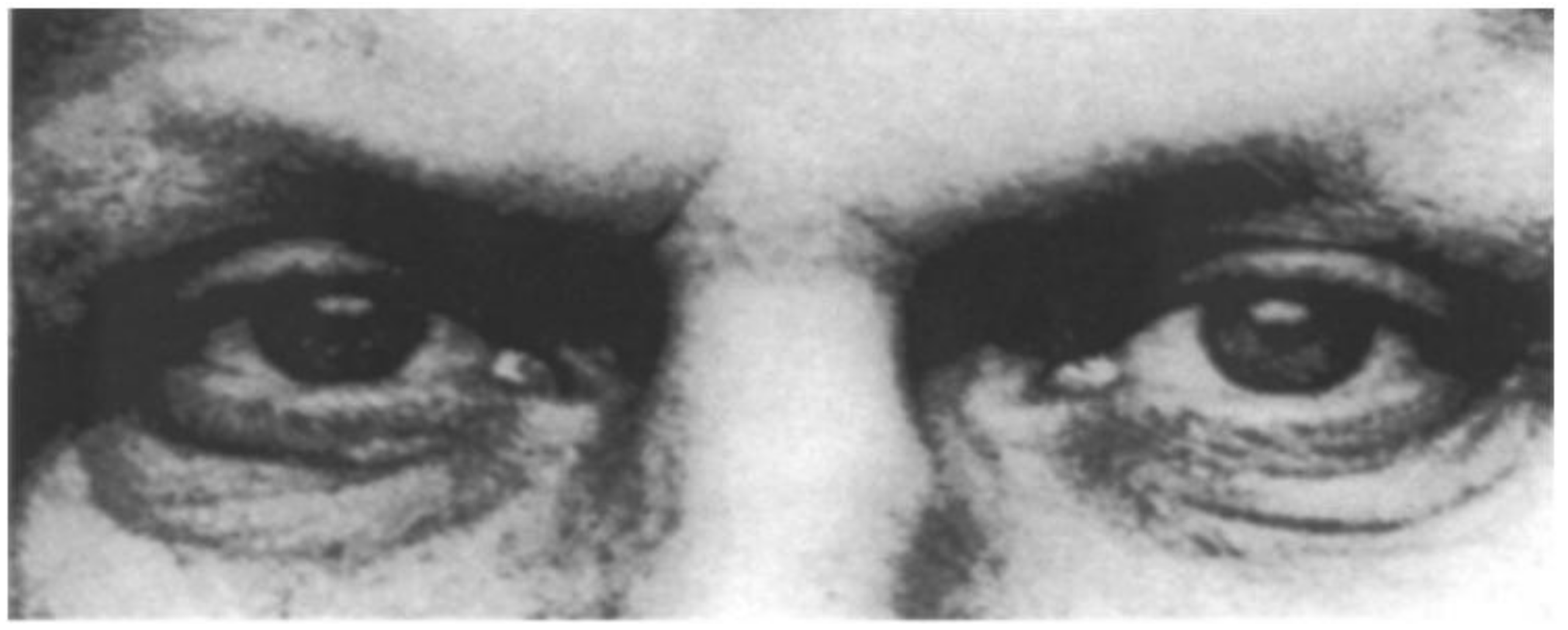

2.1. Survey

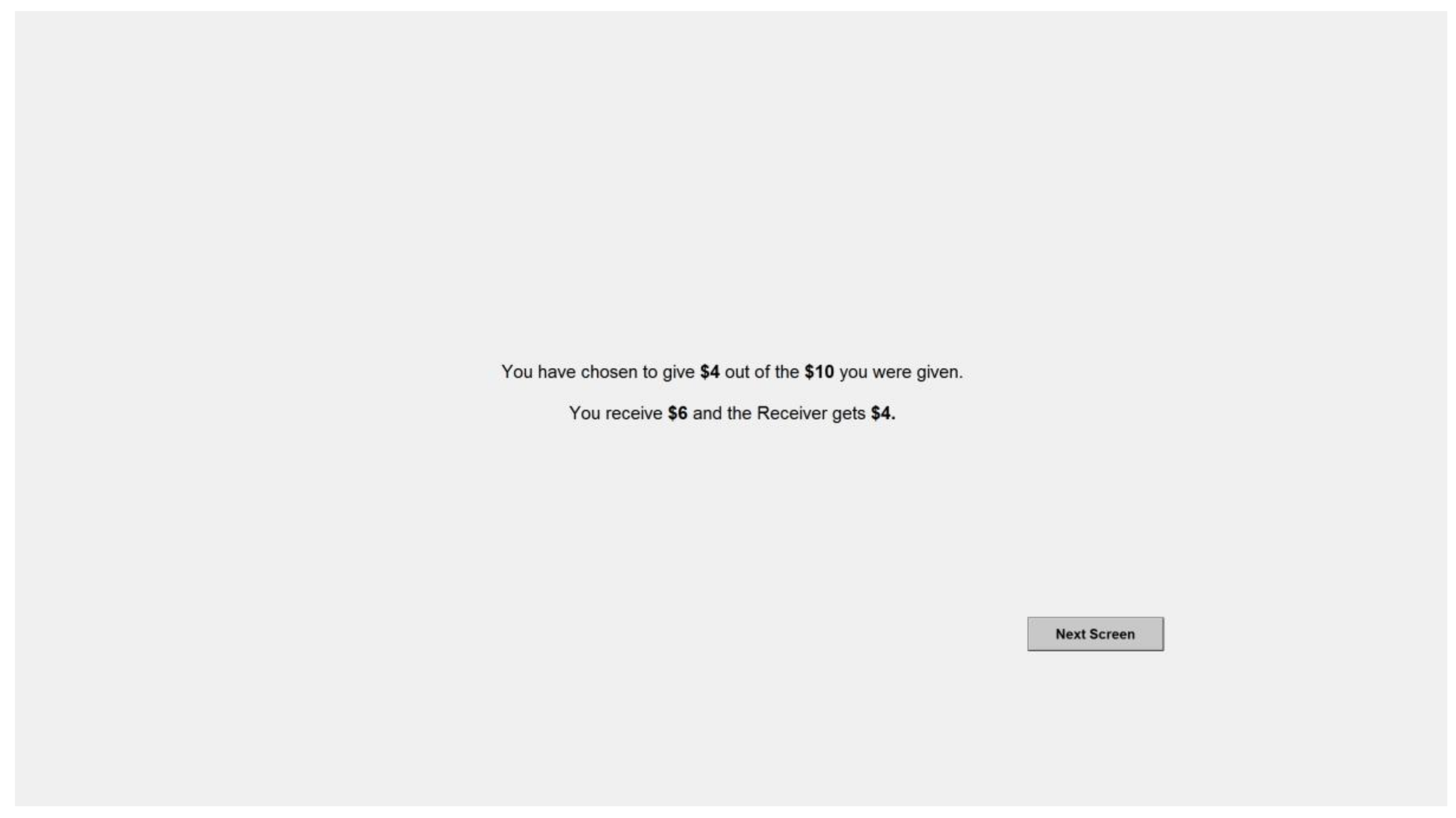

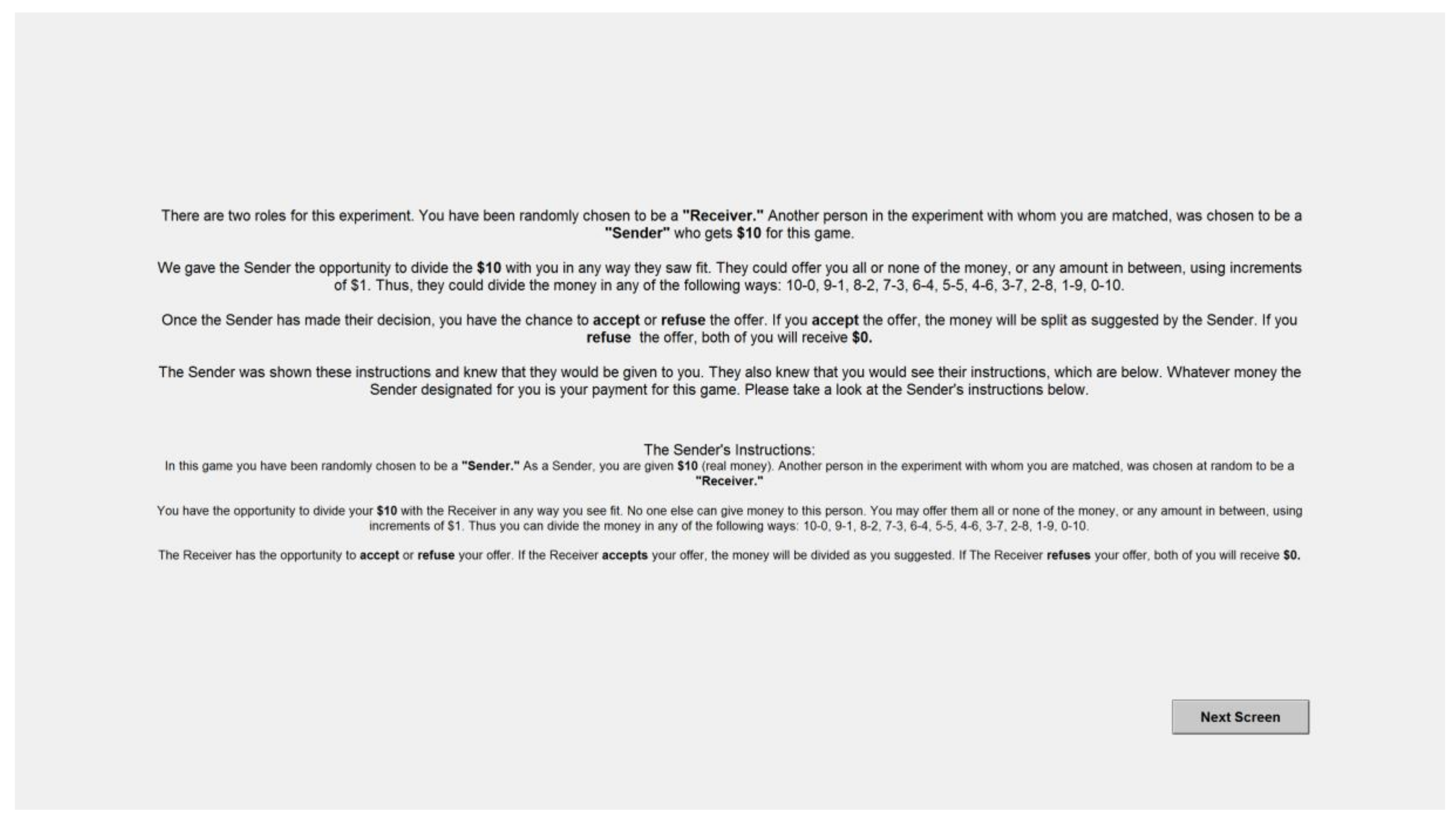

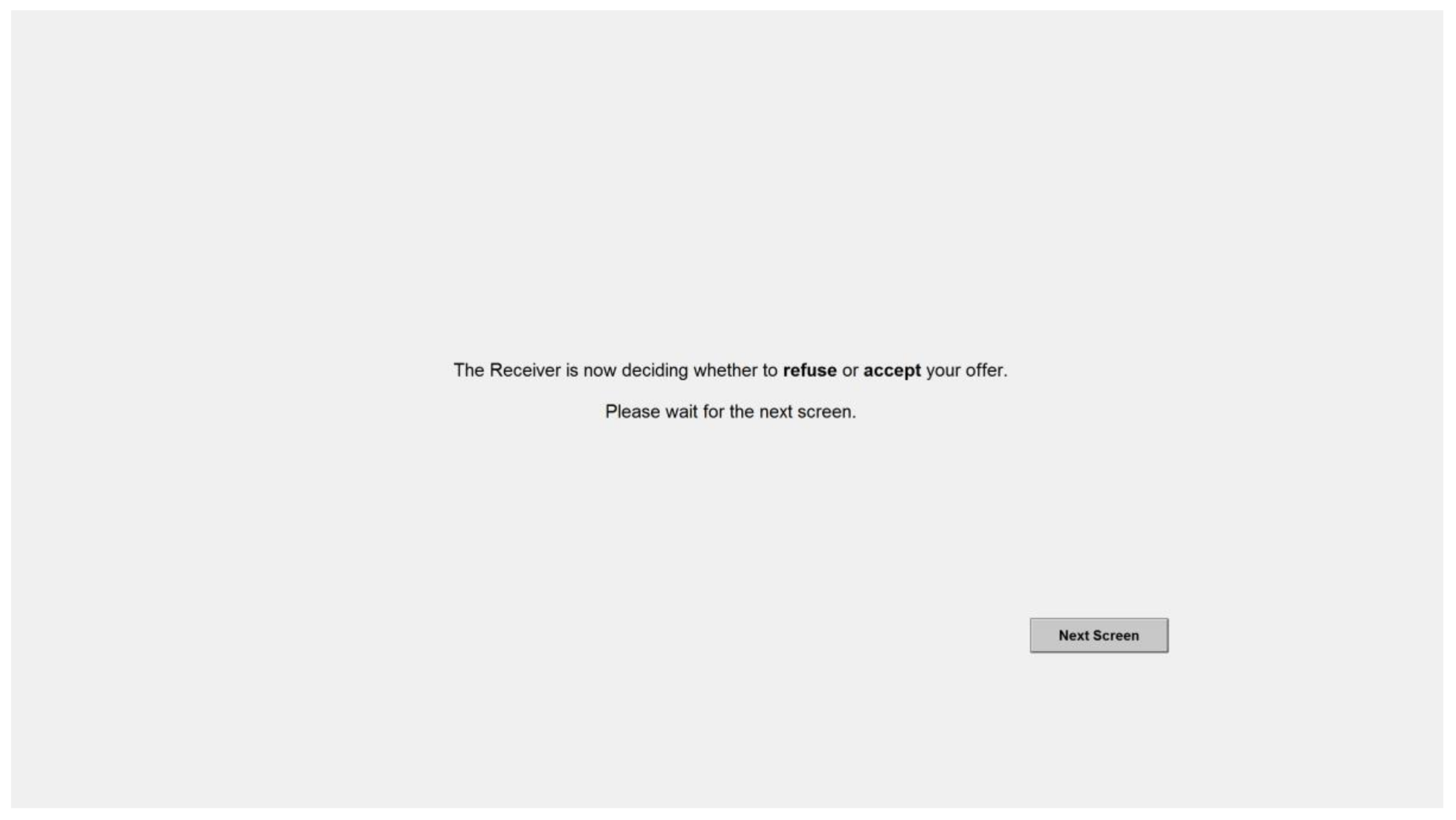

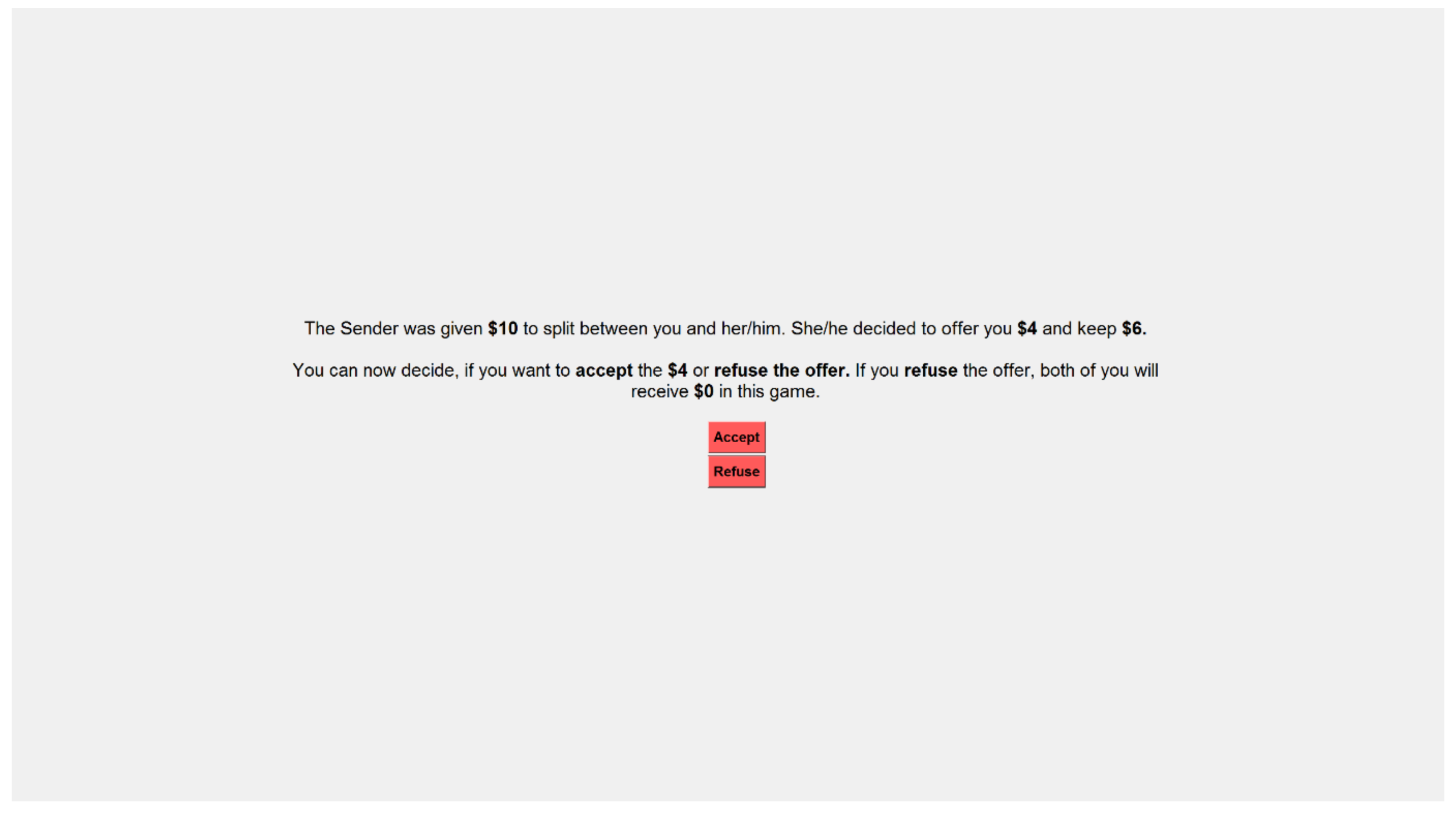

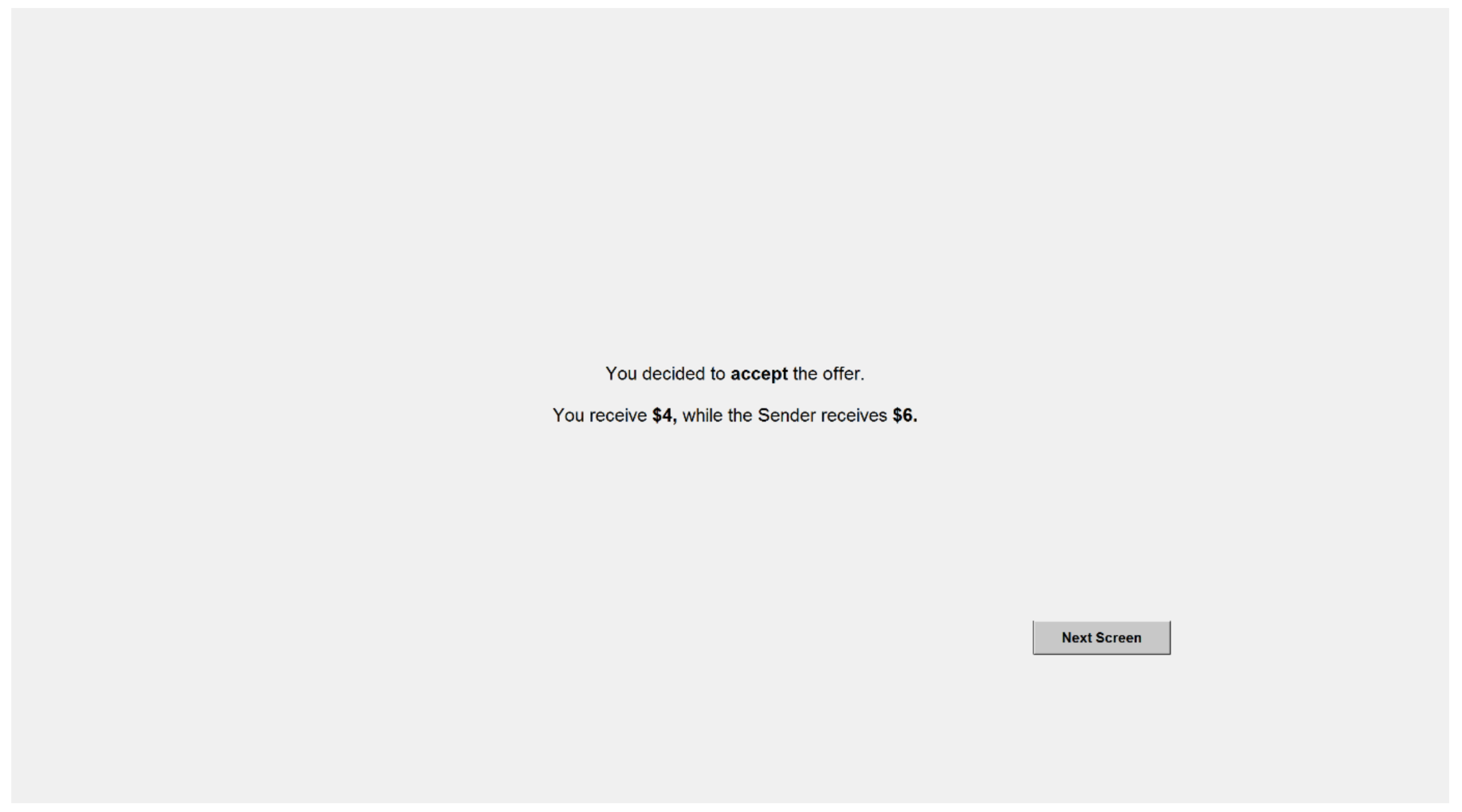

2.2. Experiments

2.3. Descriptive Statistics

3. Results

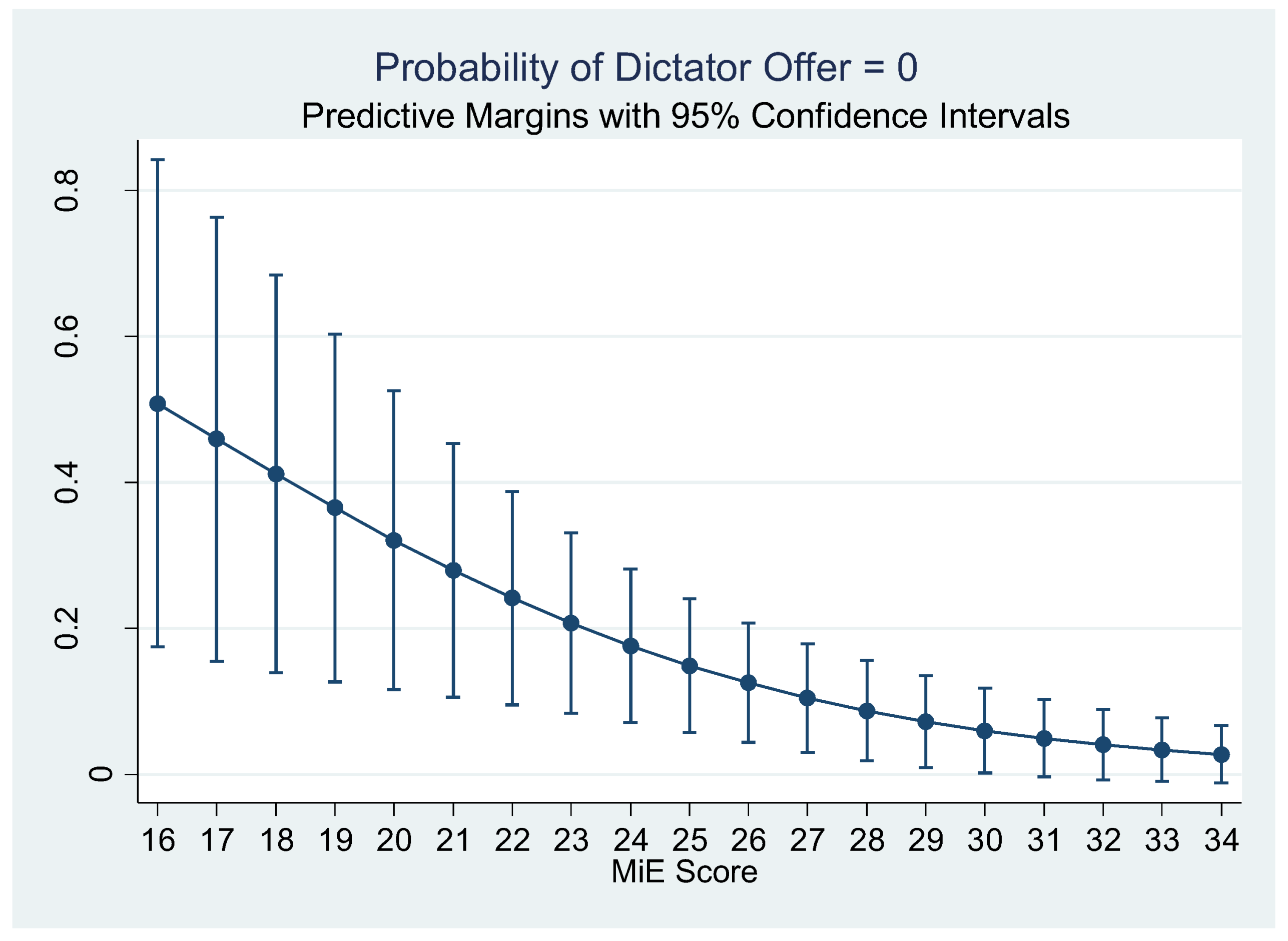

3.1. The Dictator Game

3.2. The Ultimatum Game

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Additional Models

| Variables | DG—Model 5 | DG—Model 6 | UG—Model 5 | UG—Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiE score | 0.235 ** | 0.224 ** | ||

| (0.088) | (0.075) | |||

| Wonderlic score | −0.178 * | −0.154 * | ||

| (0.072) | (0.067) | |||

| Gender | −0.233 | −0.661 | 0.268 | 0.186 |

| (0.555) | (0.498) | (0.551) | (0.605) | |

| Age | 0.129 | 0.133 | 0.138 | 0.188 |

| (0.142) | (0.165) | (0.142) | (0.143) | |

| Risk averse | 0.377 | 0.812 | 0.606 | 0.477 |

| (0.628) | (0.532) | (0.573) | (0.540) | |

| Rotation | 0.483 * | 0.294 | −0.298 | −0.164 |

| (0.243) | (0.249) | (0.226) | (0.262) | |

| Big Five—Extraversion | −0.144 | −0.017 | ||

| (0.600) | (0.356) | |||

| Big Five—Agreeableness | 0.321 | −0.408 | ||

| (0.552) | (0.478) | |||

| Big Five—Consciousness | −0.110 | −0.691 | ||

| (0.435) | (0.561) | |||

| Big Five—Neuroticism | −0.488 | 0.163 | ||

| (0.554) | (0.435) | |||

| Big Five—Openness | 0.781 | 0.562 | ||

| (0.612) | (0.447) | |||

| REI—40—Rational Ability | 0.343 | −0.379 | ||

| (0.547) | (0.435) | |||

| REI—40—Rational Engagement | 0.604 | 0.693 | ||

| (0.518) | (0.426) | |||

| REI—40—Experiential Ability | −0.543 | 0.162 | ||

| (0.728) | (0.602) | |||

| REI—40—Experiential Engagement | −0.284 | 0.126 | ||

| (0.817) | (0.556) | |||

| Control variables | None | None | None | None |

| Pseudo R² | 0.089 | 0.099 | 0.097 | 0.095 |

| BIC | 290.5 | 286.0 | 254.2 | 252.3 |

| AIC | 252.5 | 250.0 | 218.4 | 218.6 |

| N | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Wald-Chi² | 23.58 ** | 21.99 ** | 21.83 * | 24.74 ** |

Appendix B. Experimental Instructions—Online Survey

Appendix C. Experimental Instructions—Laboratory Experiment

References

- Gintis, H.; Bowles, S.; Boyd, R.; Fehr, E. Explaining altruistic behavior in humans. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2003, 24, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C.F. Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4008-4088-5. [Google Scholar]

- Leimar, O.; Hammerstein, P. Evolution of cooperation through indirect reciprocity. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2001, 268, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, M.A.; Sigmund, K. The Dynamics of Indirect Reciprocity. J. Theor. Biol. 1998, 194, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchanathan, K.; Boyd, R. A tale of two defectors: The importance of standing for evolution of indirect reciprocity. J. Theor. Biol. 2003, 224, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchanathan, K.; Boyd, R. Indirect reciprocity can stabilize cooperation without the second-order free rider problem. Nature 2004, 432, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, G.E.; Katok, E.; Zwick, R. Dictator game giving: Rules of fairness versus acts of kindness. Int. J. Game Theory 1998, 27, 269–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U. Third-party punishment and social norms. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2004, 25, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. A Theory of Fairness, Competition, and Cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 817–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Gneezy, U. What’s in a name? Anonymity and social distance in dictator and ultimatum games. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 68, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, K.J.; Fessler, D.M.T. Nobody’s watching? Subtle cues affect generosity in an anonymous economic game. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2005, 26, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnet, I.; Frey, B.S. The sound of silence in prisoner’s dilemma and dictator games. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1999, 38, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, J.L.; Kirkwood, N. Group identity and gender in public goods experiments. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2002, 48, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E.; McCabe, K.; Smith, V.L. Social Distance and Other-Regarding Behavior in Dictator Games. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 653–660. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, J.; Weber, R.A.; Kuang, J.X. Exploiting moral wiggle room: Experiments demonstrating an illusory preference for fairness. Econ. Theory 2007, 33, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, J.; Cain, D.M.; Dawes, R.M. What you don’t know won’t hurt me: Costly (but quiet) exit in dictator games. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 2006, 100, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, Z.; Van der Weele, J.J. Dual-Process Reasoning in Charitable Giving: Learning from Non-Results. Games 2017, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, B.B. Children’s Social Sensitivity and the Relationship to Interpersonal Competence, Intrapersonal Comfort, and Intellectual Level. Dev. Psychol. 1970, 2, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C. Dictator games: A meta study. Exp. Econ. 2011, 14, 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Deckers, T.; Dohmen, T.; Falk, A.; Kosse, F. The Relationship Between Economic Preferences and Psychological Personality Measures. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2012, 4, 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Tan, J.H.; Zizzo, D.J. Which is the more predictable gender? Public good contribution and personality. Econ. Issues 2010, 15, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzban, R.; Houser, D. Individual differences in cooperation in a circular public goods game. Eur. J. Personal. 2001, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Argyle, M. Happiness and cooperation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1991, 12, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B.; Peterson, J.B. Extraversion, neuroticism, and the prisoner’s dilemma. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, T.; Falk, A.; Huffman, D.; Sunde, U. Are Risk Aversion and Impatience Related to Cognitive Ability? Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 1238–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghans, L.; Heckman, J.J.; Golsteyn, B.H.H.; Meijers, H. Gender Differences in Risk Aversion and Ambiguity Aversion. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2009, 7, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, T.; Falk, A.; Huffman, D.; Sunde, U. Representative Trust and Reciprocity: Prevalence and Determinants. Econ. Inq. 2008, 46, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Jolliffe, T.; Mortimore, C.; Robertson, M. Another advanced test of theory of mind: Evidence from very high functioning adults with autism or Asperger syndrome. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Hill, J.; Raste, Y.; Plumb, I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test Revised Version: A Study with Normal Adults, and Adults with Asperger Syndrome or High-functioning Autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, O.P.; Donahue, E.M.; Kentle, R.L. The Big Five Inventory—Versions 4a and 54; University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- John, O.P.; Naumann, L.P.; Soto, C.J. Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 114–158. ISBN 978-1-59385-836-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pacini, R.; Epstein, S. The relation of rational and experiential information processing styles to personality, basic beliefs, and the ratio-bias phenomenon. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wonderlic, E.F. Wonderlic Personnel Test and Scholastic Level Exam: User’s Manual; Wonderlic and Associates: Northfield, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrough, E.O.; Robalino, N.; Robson, A.J. The Evolution of “Theory of Mind”: Theory and Experiments; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterbeek, H.; Sloof, R.; Kuilen, G. Van de Cultural Differences in Ultimatum Game Experiments: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. Exp. Econ. 2004, 7, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.R.; Mellor, J.M. Predicting health behaviors with an experimental measure of risk preference. J. Health Econ. 2008, 27, 1260–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, C.A.; Laury, S.K. Risk aversion and incentive effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, J.B.; Meier, S. Learning from (failed) replications: Cognitive load manipulations and charitable giving. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2014, 102, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsberg, D. Risk, Ambiguity, and the Savage Axioms. Q. J. Econ. 1961, 75, 643–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brañas-Garza, P.; Meloso, D.; Miller, L. Strategic risk and response time across games. Int. J. Game Theory 2017, 46, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamay-Tsoory, S.G.; Aharon-Peretz, J.; Perry, D. Two systems for empathy: A double dissociation between emotional and cognitive empathy in inferior frontal gyrus versus ventromedial prefrontal lesions. Brain 2009, 132, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wai, M.; Tiliopoulos, N. The affective and cognitive empathic nature of the dark triad of personality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | For the risk aversion parameter, we followed the set-up and pay-off structure of Anderson and Mellor [36]. Calculation of the risk aversion parameter followed Holt and Laury’s procedure of calculating the interval of the coefficient of relative risk aversion (CRRA). We then took the mean of the interval and classified participants into risk averse if the mean was above 0 and risk loving if the mean was below 0. |

| 2 | Participants played the one-urn Ellsberg paradox, where they were asked about their choice in two situations. The first situation was:

The second situation was:

If participants chose (A) and then (B), they were classified as ambiguity averse, and as “else” for all other choice combinations. Out of the 140 participants, 81 were classified as ambiguity averse, while 59 were classified as “else”. |

| 3 | Interactions between MiE scores and Wonderlic scores, as well as non-linear MiE and Wonderlic scores were examined, but showed no statistical significance. |

| 4 | Separate regressions for rotation showed a slightly smaller coefficient of the MiE score variable when the DG was played after the UG (0.18 compared to 0.22). The difference between the coefficients was not statistically significant, hence further interpretation would only be speculation. |

| Variable | Median/Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 22/21.54 | 2.07 |

| 22/21.47 | 1.96 |

| 22/21.57 | 2.00 |

| Gender (male = 1) | ||

| 1/0.607 | 0.49 |

| 1/0.600 | 0.49 |

| 1/0.657 | 0.48 |

| Risk averse (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | ||

| 1/0.779 | 0.42 |

| 1/0.800 | 0.40 |

| 1/0.771 | 0.42 |

| MiE score | ||

| 27/27.24 | 3.43 |

| 27.5/27.49 | 3.34 |

| 27/26.99 | 3.11 |

| Wonderlic score | ||

| 36/35.29 | 4.67 |

| 36/35.27 | 5.15 |

| 35/35.00 | 4.73 |

| Dictator giving | 4/3.40 | 2.03 |

| Ultimators’ Offer (83% accepted) | 4/3.89 | 1.35 |

| Dictators’ Giving Amount | USD 0 | USD 1 | USD 2 | USD 3 | USD 4 | USD 5 | USD > 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Dictators | 8 | 9 | 3 | 12 | 11 | 25 | 2 |

| MiE score | |||||||

| 25.25 | 25.44 | 29.33 | 26.58 | 28.91 | 28.36 | 29.5 |

| (4.59) | (4.36) | (4.04) | (2.68) | (2.51) | (2.40) | (3.54) |

| 17/29 | 18/34 | 25/33 | 22/30 | 26/33 | 23/32 | 27/32 |

| Wonderlic score | |||||||

| 38.38 | 32.56 | 36.67 | 36.17 | 33.64 | 35.68 | 31.5 |

| 3.85 | 7.00 | 5.51 | 4.30 | 5.68 | 4.51 | 6.36 |

| 33/45 | 19/42 | 31/42 | 29/43 | 25/42 | 27/43 | 27/36 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiE score | 0.207 ** | 0.198 * | 0.243 * | 0.243 * |

| (0.071) | (0.087) | (0.102) | (0.105) | |

| Gender | −0.599 | −0.492 | −0.699 | −0.698 |

| (0.423) | (0.431) | (0.531) | (0.545) | |

| Age | 0.139 | 0.077 | 0.062 | 0.063 |

| (0.116) | (0.154) | (0.180) | (0.197) | |

| Risk averse | 0.517 | 0.631 | 0.500 | 0.502 |

| (0.505) | (0.525) | |||

| Rotation | 0.477 * | 0.566 * | 0.563 * | |

| (0.231) | (0.241) | (0.284) | ||

| Wonderlic score | −0.047 | −0.046 | ||

| (0.056) | (0.055) | |||

| Ellsberg paradox | −0.024 | |||

| (0.643) | ||||

| Control variables | University | University, field of study | University, field of study | |

| Pseudo R² | 0.0591 | 0.1091 | 0.1642 | 0.1642 |

| BIC | 274.5 | 275.1 | 278.8 | 283.0 |

| AIC | 249.7 | 243.6 | 238.3 | 240.3 |

| N | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Wald-chi² | 11.03 * | 23.79 ** | 49.06 *** | 49.22 *** |

| Ultimators’ Offer Amount | USD 0 | USD 1 | USD 2 | USD 3 | USD 4 | USD 5 | USD > 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of ultimators | 2 | 4 | 3 | 13 | 18 | 29 | 1 |

| Acceptance rate | 0% | 50% | 33.3% | 53.85% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Final amount received | $0 | $4.5 | $2.67 | $3.77 | $6 | $5 | $4 |

| Wonderlic score | |||||||

| Mean | 35.5 | 36.25 | 39.33 | 37.92 | 35.39 | 32.79 | 35 |

| SD | (6.36) | (5.62) | (4.73) | (3.61) | (3.90) | (4.75) | (.) |

| Min/Max | 31/40 | 29/42 | 34/43 | 32/45 | 27/43 | 19/40 | 35/35 |

| MiE score | |||||||

| 28.5 | 27.25 | 27.67 | 26.77 | 27.00 | 26.76 | 30 |

| 2.12 | 2.75 | 1.53 | 2.49 | 3.99 | 3.14 | . |

| 27/30 | 24/30 | 26/29 | 22/32 | 19/32 | 18/33 | 30/30 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wonderlic score | −0.167 ** | −0.131 * | −0.115 ° | −0.103 |

| (0.057) | (0.064) | (0.068) | (0.075) | |

| Gender | 0.166 | 0.554 | 0.348 | 0.354 |

| (0.498) | (0.622) | (0.655) | (0.662) | |

| Age | 0.140 | 0.070 | 0.066 | 0.071 |

| (0.157) | (0.105) | (0.105) | (0.106) | |

| Risk averse | 0.539 | 0.371 | 0.354 | 0.374 |

| (0.522) | (0.563) | (0.577) | (0.581) | |

| Rotation | −0.050 | −0.071 | −0.049 | |

| (0.238) | (0.257) | (0.262) | ||

| MiE score | −0.059 | −0.068 | ||

| (0.066) | (0.068) | |||

| Ellsberg paradox | −0.405 | |||

| (0.599) | ||||

| Control variables | University | University, field of study | University, field of study | |

| Pseudo R² | 0.0724 | 0.129 | 0.143 | 0.146 |

| BIC | 235.7 | 236.7 | 250.7 | 254.4 |

| AIC | 213.2 | 207.5 | 212.5 | 213.9 |

| N | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Wald-Chi² | 16.48 ** | 27.59 *** | 30.22 ** | 30.82 ** |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lang, H.; DeAngelo, G.; Bongard, M. Theory of Mind and General Intelligence in Dictator and Ultimatum Games. Games 2018, 9, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020016

Lang H, DeAngelo G, Bongard M. Theory of Mind and General Intelligence in Dictator and Ultimatum Games. Games. 2018; 9(2):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020016

Chicago/Turabian StyleLang, Hannes, Gregory DeAngelo, and Michelle Bongard. 2018. "Theory of Mind and General Intelligence in Dictator and Ultimatum Games" Games 9, no. 2: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020016

APA StyleLang, H., DeAngelo, G., & Bongard, M. (2018). Theory of Mind and General Intelligence in Dictator and Ultimatum Games. Games, 9(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020016