Abstract

Many people implicitly sell or give away their data when using online services and participating in loyalty programmes—despite growing concerns about company’s use of private data. Our paper studies potential reasons and co-variates that contribute to resolving this apparent paradox, which has not been studied previously. We ask customers of a bakery delivery service for their consent to disclose their personal data to a third party in exchange for a monetary rebate on their past orders. We study the role of implicitly and explicitly stated prices and add new determinants such as political orientation, income proxies and membership in loyalty programmes to the analysis of privacy decision. We document large heterogeneity in privacy valuations, and that the offered monetary benefits have less predictive power for data-disclosure decisions than expected. However, we find significant predictors of such decisions, such as political orientation towards liberal democrats (FDP) and membership in loyalty programmes. We also find suggestive evidence that loyalty programmes are successful in disguising their “money for data” exchange mechanism.

Keywords:

data protection; data privacy; explicit prices; information economics; consumer behaviour; personal data; field experiment JEL:

C93; D19; D91

1. Introduction

Companies are gathering more and more detailed data about individuals’ preferences and behaviour. Data has even been termed the “new oil” (Rotella [1]). At the same time, people seem to be more and more concerned about companies gathering and using their private data (e.g., Madden et al. [2]). However, many people implicitly sell or give away their data when using online services and participating in loyalty programmes. In the literature, this seeming paradox behaviour has been related to a lack of clarity of data-involving transactions. In particular, scholars have argued that often, the costs of such transactions in terms of a privacy loss are hidden or unclear (e.g., Tsai et al. [3]). We would claim that very often, the benefits are not very clear either. In standard loyalty programmes, customers are promised a certain percentage of their future purchases; however, we posit that few customers have a good estimate of what this means in monetary terms. Also, according to a study in which the most popular loyalty programme in Germany commissioned, customers overestimate the benefits: in the eyes of the customers, the “points” they earn when making their purchases are up to 2.6 times as valuable as their real value in money.1

In this paper, we conduct a field experiment with customers of a delivery service for bakery products, to answer whether people take into account the (often low) level of benefits that come with loyalty programmes. Surprisingly, making them aware of the exact level of benefits does not clearly change people’s data-disclosure choices in our experiment. Rather, the data suggest a threshold effect: apart from the 25% of people who always consent to their data being transferred, more customers agree to give consent only when the offer exceeds 5–6 Euros. In addition, for those high offers, our hypotheses seem to bear out: there is a weak correlation between offered benefit and consent if the price is only implicitly given, while the correlation is stronger when the price is made explicit.

We further find suggestive evidence that the determinants of the data-disclosure decisions differ from the determinants of the decision to participate in loyalty programmes. This would lend support to the idea that loyalty programmes successfully disguise the fact that their customers effectively trade data for the offered rebates. Thus, it seems that it is both the masking of costs and uncertainty about the benefits that ultimately provide an answer for why so many people join the loyalty programmes.

Finally, we are interested in additional determinants of data-disclosure decisions. This is useful, for example, to make the above-mentioned comparisons of whether different data-privacy related decisions are driven by the same factors, or whether they are qualitatively different. Here, we only find that individual’s political and privacy-related inclinations play a role, while their age or the length of the business relationship with the company do not seem to play a role.

Research on data privacy in economics has been extensive. Acquisti, Curtis, and Wagman [4] provide an extensive review of the vast field of theoretical and empirical economic literature investigating individual and societal trade-offs associated with sharing and protecting personal data. In the following, we focus on a review of recent experimental studies that are relevant to our research.

Our approach of measuring the value of privacy in a field experiment of different pricing set-ups rest upon a study by Acquisti, John, and Loewenstein [5] who established that differences in the framing of a data transfer would result in different elicited valuations. A transfer of personal data framed in an endowment-effect setting (an individual having to give up some of the money she or he had previously received unconditionally) would result in significantly lower “willingness to pay” for privacy, while a transfer which would result in an additional amount of money being transferred in return for private information exhibited a higher “willingness to accept”. Hence, Acquisti et al. [5] concluded that there is no one price of privacy and questions the individual’s ability in navigating privacy issues.

Beresford, Kübler, and Preibusch [6] conducted an experiment using an online DVD shop to determine customers’ willingness to pay for privacy. They compared two online shops with differing requests for private information from their customers. Customers consistently bought the cheaper product regardless of the privacy implications.

Both Acquisti et al. [5] and Beresford et al. [6] focus on situations in which the privacy costs are not particularly salient. Tsai et al. [3] point out that privacy policies are not easily understood and use a laboratory experiment to show that participants are willing to pay a premium for privacy if privacy protection is clear and easily distinguishable between online shops. Other determinants of the privacy valuation such as too much transparency can reduce drastically the willingness to disclose data or even to participate (Regner and Riener, [7]). In a natural field experiment, the number of sales at a ‘pay-what-you-want’ music shop declined drastically after the introduction of a new privacy policy revealing the names of the buyers. This would hint at quite a high value of privacy and, of course, a high degree of salience in this natural experiment. Marreiros et al. [8] also found that participants in their experiment adopted a more reluctant approach towards information disclosure once privacy handling practices of companies were made more salient. Similarly, Benndorf, Kübler, and Normann [9] documented that in their experiment, informational unravelling occurred less often when the private information was framed as “worker’s health status” compared to a neutral frame.

Benndorf and Normann [10] argued that there are three significant issues for the differences in results between the different studies regarding the value of privacy: incentives, salience, and transparency. They designed a controlled laboratory experiment that catered to all three of the issues and found heterogeneity between participants as one of the six participants did not give up their data, while the remainders’ valuations differed substantially. Schudy and Utikal [11] also found a large degree of heterogeneity in privacy valuation depending on the recipients and the content of information that was disclosed. Increasing the number of recipients of the personal data provided decreasing utility to the participants of their experiments.

In our field experiment, customers know exactly that they are making a direct decision on exchanging their personal data for a fixed amount of money: they would receive the money only if their personal data can be passed on for marketing uses by the company’s business partners. Thus, there is an obvious trade-off between privacy and money, which means incentivization, salience, and transparency are all given. Our data set is quite rich, so that we can control for membership in loyalty programmes, income, and political inclination. Hence, we add to the existing literature by considering additional determinants of data-disclosure decisions that have not been investigated so far. In fact, some of the factors we consider can only be included in a field setting, such as age (which does not vary much within the laboratory) or the level of trust (which we proxy by the length of the relationship).

2. Experimental Setting

For our field experiment, we partnered up with a delivery service of bakery products operating in southern Baden-Württemberg, a German Land (federal state) bordering with France and Switzerland. At the time, the delivery service covered 183 customers in and around five small cities (Gottmadingen, Hilzingen, Radolfzell, Singen, and Konstanz). Customers could order different bakery products from a menu, at the same time specifying how often, how regularly, and on what dates they wanted the ordered food. Virtually all customers paid their orders by direct debit at the end of the month (the remaining 7 being invoiced).

In general, customers would not interact with the drivers delivering the products. Rather, drivers would place the delivery in some pre-agreed area. The majority of the customers would place their orders through the company website while a small number of older customers would call in. Whenever the delivery service had to get in touch with its customers, they would have a telephone agent (always the same agent) call them. This would happen about once every two or three months, usually before the major holidays.

As we wanted to use a setting that would feel as natural as possible to the customers, we also had the known telephone agent call on our behalf. We scripted a guided interview for our experiment.2 In the phone conversation, the telephone agent would refer to past marketing campaigns that the delivery service had operated in collaboration with other companies. Then, the telephone agent would ask the customers if their personal contact data could be passed on to such business partners. As a bonus for their consent, customers were offered five percent of their orders of the past three months, which would be deducted from their current month’s bill. In a baseline treatment, the phone agent would not offer the exact amount of money and was never asked to do so. In the price treatment, in contrast, the phone agent would also state the exact amount of money customers would receive in exchange for their consent. This way, we were able to investigate the differences between implicit and explicit prices in data-disclosure decisions. After the customers made their decision on whether to trade their data or not, we elicited in a final question of whether they were already participating in a loyalty programme.

In total, we have 177 households in our sample, randomly split into 88 households in the baseline condition and 89 in the price condition. We did not reach 3 households, and 3 people refused to talk to our assistant altogether after being asked for their birth dates (at the very beginning of the call, “for [the company’s] internal statistics”). The telephone calls took place in January and early February 2014.

3. Hypotheses

3.1. Main Hypotheses

Our initial conjecture was that many of those who participate in bonus-card programmes would fail to estimate the actual monetary benefits of participating, by rather focusing on some (categorical) notion of a “bonus to be had”. Thus, under typical conditions, participants would give their consent to a data transfer or not, irrespective of the monetary benefit. Hence, our first main hypothesis was:

H1.

In our baseline condition, there is no correlation between the monetary benefit offered to customers and the customers’ decision to consent to a data transfer.

In contrast, our treatment intervention made the exact monetary benefits explicit. Because of that, we posited that in our price condition, customers would perceive the situation more like a typical market transaction, in which the question is whether the price offered for the data is higher than their willingness to accept. Thus, we posited:

H2.

In our price condition, customers condition their consent to a data transfer on the monetary benefit they would get out of the trade.

Judging by the success of bonus programmes (in Germany, about 30 million customers participate in the most popular “payback” programme alone (according to https://www.payback.net/de/ueber-payback/, accessed on 4 October 2017)), people often consent to give away their data under rather low-powered incentives. In prior studies that specified monetary benefits, however, a vast majority of participants usually specify a non-negligible acceptance threshold (e.g., Benndorf and Normann [10]). In combination, we expect the coefficient of the treatment dummy in our regressions to be significantly negative.

Finally, we expected customers to consent more readily if they are reportedly having participated in a bonus programme previously, for two reasons. First, by entering a bonus programme, they have revealed to have low concern for data privacy; and second, given their data is “out there” already, the expected privacy costs are likely to be smaller than the customers who do not participate in any bonus programmes.

H3.

Customers who report participating in a bonus programme will consent to a data transfer more (and at lower monetary benefits) than the customers who report not having participated in any such programmes.

3.2. Secondary Hypotheses

For a customer to refuse a data-for-money trade, the person has to value data privacy. A person who values data privacy, in turn, will be more sensitive to what data is to be transferred, and to why we would elicit data in the first place. As we posit that the more sensitive people are more likely to ask about the data being transferred, and about the reasons for our elicitation of their year of birth, we predict that we can use the questions as a measure of people’s sensitivity with respect to privacy issues. Hence, we expected:

S1.

Those customers who ask back about data-related issues will be less likely to consent.

Given that the consent decision may also be a question of trust in the company—in that the company would not give away data to others who would misuse the data—and that long-term clients are more likely to have built trust towards the company, we also expected that:

S2.

Long-term clients consent more often.

One could also think about why customers’ age may play a role. However, it was not clear to us which way this should go, so we did not have a clear preconception about the role of customers’ age.

Finally, we elicited a proxy for participants’ political inclinations. To do so, we obtained data on the voting outcomes from the last election of the German Bundestag (i.e., parliament) prior to our experiment (the 2013 election) for each customer’s electoral sub-district (each sub-district in our sample was made up of between 125 and 1377 voters). To obtain a plausible hypothesis relating parties’ voting outcomes in an electoral sub-district and the decision to consent to a transfer for one’s data, we did two things: (i) we assumed that a higher percentage of votes for a party X within a sub-district is associated with a higher probability of a customer living in that district to vote for party X, and hence, with a higher probability of sharing that party’s ideas about data privacy. And (ii), we studied the different parties’ policy proposals with respect to data privacy as portrayed in the media before the election. In particular, we focused on the portrait of one of the central news broadcasts in German television (the “Tagesschau”, also available online).3 The resulting hypothesis is:

S3.

Customers in districts with high votes for the “Pirate” party (Piratenpartei), the social democrats (SPD), the Greens (Die Grünen), and the socialists (Linke) are less likely to consent to a transfer of their data; customers in districts with high votes for the Christian democrats (CDU), the rightist AFD, and the liberal democrats (FDP) are more likely to consent to a transfer of their data.4

4. Results

Prior to testing the current hypotheses, a brief overview of the data is presented. In Table 1, we depict summary statistics of the main variables of interest, as well as some sociodemographic data of our sample. The randomisation of participants into two treatments led to an almost perfect split of the sample (the randomisation also worked with respect to the offered monetary benefits, cf. Figure A1 in the Appendix A). Out of 174 people whom we offered between 0.25 and 28.41 Euros, 30.5% consented to sharing of the data. 73% of our sample was female, with ages ranging from 25 to 87 years. Roughly half of our sample had already participated in another bonus programme, and the average customer had been a customer of the company for about 2.5 years.

Table 1.

Data overview.

4.1. Main Results

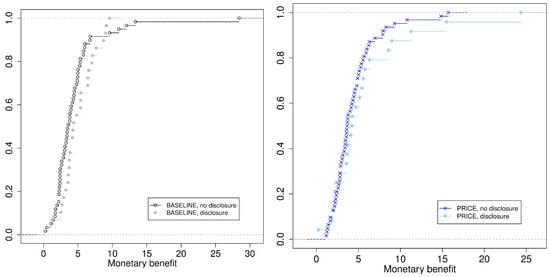

We first provide a graphical representation of the relationship between the amount offered and the decision to consent to a data transfer. Figure 1 shows the distributions of amounts offered before a consenting decision vs. before a declining decision, for treatments baseline and price, respectively. We see a slight trend towards consenting decisions being associated with higher offers that become pronounced only in the price treatment for offers of 6.30 € and above.

Figure 1.

Distributions of amounts offered before a consenting decision vs. before a declining decision, for treatments baseline (left) and price (right).

To test our main hypotheses, we rely on linear probability models.5 In Table 2, we regress the probability of consent to a data transfer on the main variables of interest in hypotheses H1, with and without additional control variables. In Model 1, the explanatory variables are the monetary benefit we offered for consent, the treatment condition, and the interaction effect between monetary benefit and condition. We expected the coefficient of the monetary benefit to be 0 (H1), the interaction effect to be positive (H2), and the treatment dummy to be negative. Our data do not provide evidence against hypothesis H1, but also no evidence for hypothesis H2: the coefficient of the monetary benefit is small and not significantly different from zero, and the same holds true for the additional effect of monetary benefit in the price condition. In Model 2, we test Hypothesis H3: the coefficient of participating in another bonus programme is substantial and positive. As observed from the second column in Table 2, hypothesis H3 is indeed supported by the data. Participating in another bonus programme is associated with a 16 percentage points higher probability of consent. Model 3 adds a number of control variables to the earlier regressions (none of which have coefficients that are significantly different from zero).6

Table 2.

Tests of H1 to H3 by regressions of linear probability models. The dependent variable is the probability of consent, the regressors are the main variables of interest in hypotheses H1 to H3, as well as a variety of controls in Models 3 and 6.

Models 4 to 6 explore the idea that higher offers increase the probability of consent only when they are above a certain threshold; when they are too low, consumers may simply not take them seriously.7 Here, we use the highest quartile of offers as ‘potentially large-enough offers’. The results suggest that in our sample, it is indeed the case that high-enough offers make consent more likely (“Benefit in 4th quartile” in Table 2). Surprisingly, this only holds for the baseline condition (“Benefit in 4th quartile x price trmt” offsets the above effect). At the same time, there is a slight indication that for high-enough offers, the probability of consent depends more strongly on the offered amount in our price condition than in our baseline condition (as suggested by Figure 1 and the triple interaction in the last row of Table 2)—which would have been in line with our initial conjecture.

So far, we have seen that the expected privacy costs seem to influence the consent decision (as proposed by H3). In terms of our H1, the picture is less clear: Models 4 to 6 suggest that high-enough offers lead to higher rates of consent in a step-level fashion (in contrast to H1), but only in the baseline condition. For the price condition, the absolute step-level effect is missing, but for high-enough offers, the association of offered amount and probability of consent seem to be stronger than in the baseline condition (which would be in line with H2).

To address our secondary hypotheses, we will focus on the marginal effects of probit regressions, as we do not mean to interpret any interaction effects here.8 We expected that those customers who ask back would be more reluctant to give away their data. Regressions of Models 7 and 8, reported in Table 3, show no conclusive evidence on this question: while the coefficients on our “questions” variable are in the expected direction, they remain insignificant, with or without the additional controls in place. Similarly, customers’ age and their status as a long-term client do not significantly affect the consent decision in any of our regressions.

Table 3.

Models testing our secondary hypotheses (N.obs. = 172 for all models).

In line with hypothesis S3, the vote share of the liberal democrats (FDP, between 2.6% and 15.7%, with a mean of 7.0%) in the electoral sub-district (between 125 and 1377 voters in our sample) is one of the most robust predictors in our sample. This mirrors the party’s public image as an economy-oriented/business-friendly party. Surprisingly, in contrast to hypothesis S3, the vote shares of CDU and AFD did not help to predict data-transfer decisions.

4.2. Exploratory Analysis: Determinants of Consent vs. Bonus-Programme Participation

So far, our analysis seems to show that customers weigh the benefits and costs at least to some degree when making their decision on whether to consent to a data transfer. What seems different in our study compared to every-day-life situations in which data is transferred is that in our study, we openly ask for customers’ approval to pass their data onto some other company. In this final section, we perform an exploratory analysis that suggests that the two situations may, indeed, be different from the consumer perspective. For this purpose, we regress both the decision to consent to a data transfer and the—historical—decision to participate in a loyalty programme on all of our control variables that might influence the decision to participate in a loyalty programme. We omit the “benefit”, “another programme”, and “long-term clients” variables from our earlier models, to put the regressions on data-transfer consent and on loyalty-programme participation on equal footing. In Table 4, we present the results of a linear probability model and the marginal fixed effects of a probit regression for each of the two decisions. All models include random effects for the customers’ postal code.

Table 4.

Regression analyses of the decisions on data-transfer consent and bonus-programme participation using the same explanatory variables.

The models reported in Table 4 suggest that the decision to consent to a data transfer in our field experiment is a decision that is qualitatively different from the decision to participate in a loyalty programme. The main predictor for the decision to give consent to a data transfer (after removing the offered benefit and “another programme”) is still the probability of having voted for the liberal democrats (FPD). Note that the FDP variable affects the programme-participation decision negatively, if at all. The main predictor for participating in a loyalty programme is the customers’ preferred mode of interaction with our delivery-service company: if they are happy to share their e-mail address and use it for market interactions, they are also more likely to participate in a loyalty programme. There is no noticeable analogous effect on the consent decision. Note that this is not merely an age effect, as we are controlling for age in all models in Table 4. A second potential determinant of participating in loyalty programmes could be wealth, as measured by the standard land value. However, the reasons for such relationships are not immediately obvious. The relationship of wealth and the consent decision, in any case, is negative, if there was a relationship to exist at all.

5. Discussion

The high take-up rates of loyalty programmes seem to be in contradiction to many people’s growing concern about data privacy. In this paper, we investigate whether uncertainty about the monetary benefit of a data-involving trade contributes to the widespread participation in such programmes. We do not find evidence that it does; in fact, in our baseline condition, consent rates depend on whether the offer corresponds to a high (-enough) monetary value or not. The data for offers in the lower three quartiles of the offered-benefit distribution might suggest that there are approximately 25% of the people who consent for any benefit (we do not see statistical evidence that these people condition their consent decision on the benefit). Others seem to condition their choices on whether the offer is “high enough”, where the cut-off seems to be in the vicinity of 5–6 € for our sample. Our observations correspond roughly to the findings of [10], who found that 10–20% sell their data for even very low offers, and 30% are willing to sell their contact data when offered 5 € or more.

When we explicitly quote the monetary benefit of the data trade, the conditioning on the benefit seems to become stronger, albeit only when the benefit falls in the highest quartile of the offered-benefit distribution. Therefore, while uncertainty seems to be playing a role, it does so only when the benefit is large enough. Having said this, we should also note that the degree of uncertainty we induced is comparatively low, given that the monetary benefit is already fixed at the time of the offer. In the decision of whether to join a loyalty programme, the uncertainty about the monetary benefits will be certainly higher. For an experiment, however, offering a rebate on future earnings would be plagued with endogeneity concerns.

We find suggestive evidence that the determinants of decisions on data disclosure are different when the trade involves a transfer of data—as in our experiment—than when this transfer of data is not made clear—as in the usual loyalty programme. Overall, it seems that both the masking of costs and uncertainty about the benefits ultimately provide an answer to why so many people join loyalty programmes, most likely in conjunction with the trick of showing the benefits in terms of “points” rather than actual Euro cents.9

The second topic of our study is about other factors influencing people’s decisions to consent to a transparent data transfer. The two variables that robustly contributed to explaining consent decisions were whether the customers already participated in another loyalty programme, and their support for the most business-friendly political party, as proxied by its vote share in the customer’s electoral sub-district at the most recent election. Variables such as age or the length of the business relationship with the delivery service did not play any significant roles.

We can only speculate about why participating in a loyalty programme predicts the data-disclosure decisions in our data set, as there are clearly two possible reasons: on the one hand, participating in a loyalty programme means that one’s data is available to many firms already, so the costs of revealing it to additional firms will be lower. On the other hand, participation in a loyalty programme simply may reveal the corresponding customer’s lack of privacy concerns.

With respect to the effect of political orientation on whether customers consented to a data transfer, what is surprising is how political orientation and decisions are weakly correlated, but the fact that the effect seems to be so strong that we were able to find it in our data. Judging by our estimates, going from the electoral sub-district with the fewest votes for the liberal democrats (FDP) to the sub-district with the most FDP-votes increases the chances of obtaining consent by roughly 1.5 percentage points.10 This seems very small; however, if we could extrapolate directly from our regressions, this would mean that a FDP-voter is about 11 percentage points more likely to give consent to a data transfer than a non-FDP-voter. Of course, this effect needs to be replicated in future studies before it should be considered for the public debate. However, it is the first piece of evidence that political convictions may play an important role in customers’ decisions on whether to maintain data privacy.

Author Contributions

Both authors conceived and designed the experiment; J.P. took the lead in the preparation of the data, as well as in obtaining and matching the complementary data (e.g., standard land value, political-attitude proxy); I.W. analyzed the data; both authors wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

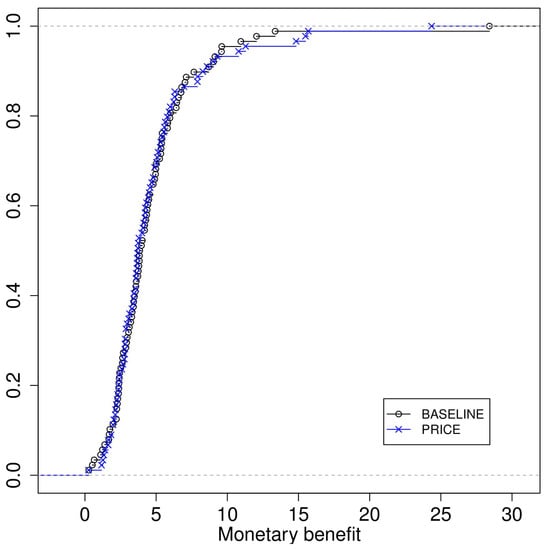

Appendix A. Supplementary Figure: Offered Benefits by Treatment

Figure A1.

Offered monetary benefits by treatment.

Appendix B. Script for the Guided Interview (Translated from German)

[Name of the company, name of the call agent], a very good day to you. Am I talking to [name of the customer]?

Today, we would like to inform you about some new developments at our company. Before that, though, I would briefly need your year of birth for our internal statistics…

Potential inquiries:

In the past, we already have conducted some sales campaigns for new customers with [well-known brand for juice] and [well-known brand for butter]. In the future, we are planning additional campaigns and we would want you as a regular customer also to benefit from them.

Potential inquiries:

For this purpose, we would like to share your contact data with our partners, and as a little bonus, we would like to offer you a credit note over 5% of your orders of the past three months. [price condition: We just calculated this for you, in your case, this would be X EUR.] Would you be fine with that?

Potential inquiries:

- → if yes: Thank you very much, we will subtract the corresponding amount from your invoice for January.

- → if no: What a pity, but we, of course, respect that.

We are also considering joining a loyalty programme such as Payback or the “Deutschland-Card” or creating one ourselves. Are you already participating in such a programme?

References

- Rotella, P. Is Data the New Oil? Forbes Magazine. 2012. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/perryrotella/2012/04/02/is-data-the-new-oil/#59a92a517db3 (accessed on 28 January 2018).

- Madden, M.; Rainie, L.; Zickuhr, K.; Duggan, M.; Smith, A. Public Perceptions of Privacy and Security in the Post-Snowden Era. Pew Research Center, 2014. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/11/12/public-privacy-perceptions (accessed on 19 March 2018).

- Tsai, J.Y.; Egelman, S.; Cranor, L.; Acquisti, A. The Effect of Online Privacy Information on Purchasing behaviour: An Experimental Study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2011, 22, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquisti, A.; Taylor, C.; Wagman, L. The Economics of Privacy. J. Econ. Lit. 2016, 54, 442–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquisti, A.; John, L.K.; Loewenstein, G. What Is Privacy Worth? J. Leg. Stud. 2013, 42, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresford, A.R.; Kübler, D.; Preibusch, S. Unwillingness to pay for privacy: A field experiment. Econ. Lett. 2012, 117, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regner, T.; Riener, G. Privacy Is Precious: On the Attempt to Lift Anonymity on the Internet to Increase Revenue. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2017, 26, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marreiros, H.; Tonin, M.; Vlassopoulos, M.; Schraefel, M.C. Now that you mention it’: A survey experiment on information, inattention and online privacy. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2017, 140, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benndorf, V.; Kübler, D.; Normann, H.-T. Privacy concerns, voluntary disclosure of information, and unraveling: An experiment. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2015, 75, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benndorf, V.; Normann, H.-T. The Willingness to Sell Personal Data. Scand. J. Econ. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schudy, S.; Verena, U. You must not know about me’—On the willingness to share personal data. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2017, 141, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | https://www.payback.net/en/press/press-releases/detail/studie-zeigt-punkte-schlagen-geld/, last accessed on 4 October 2017. |

| 2 | A translated version of the script can be found in the Appendix B. |

| 3 | https://www.tagesschau.de/wahl/parteien_und_programme/programmvergleich datenschutz100.html, latest update: 22 August 2013; latest access on 6 October 2017. |

| 4 | While the CDU and AFD did not seem to address the issue of data privacy in their programmes at all, the FDP mainly focused on protection of citizen data against governmental intrusion. |

| 5 | Looking at marginal effects of probit regressions yields the same conclusions, but given we want to interpret interaction effects, we rather stick to a linear probability model. Using a linear probability model does not seem to be too troublesome, either. The a-priori probability of giving consent is nowhere close to the boundaries, and predicted values are rarely outside of [0, 1] for most of the models reported in the following (cf. the corresponding row in Table 2). |

| 6 | In particular, we control for the main customer’s age; for whether the customer is a long-term client (>365 days); for whether the customer asked back about data-related aspects; for whether the customer’s home is located in a development area, interacted with the standard land value and a standard land value normalised by the standard land value of the (nearby) town; and for additional area-specific characteristics by including random effects for the postal code. |

| 7 | We are grateful to an anonymous referee who suggested this approach. |

| 8 | None of the qualitative statements changes if we stick to linear probability models also in this part. However, we would have up to 9 predicted probabilities outside of [0, 1] for some of these models, which is another argument in favour of using the probit regressions reported in the text. |

| 9 | Note, however, that some of the findings of Benndorf and Normann [10] seem to contradict this conclusion. In particular, their take-it-or-leave-it treatments shows high consent rates under an offer of 5 € even though both costs and benefits are made salient (in their willingness-to-accept treatments, costs are also salient, but requested benefits are much higher). Similarly, in Acquisti et al. [5], many customers sell their data, being identifiable for as little as USD 2, but there, the costs are somewhat limited: the data are sold to the researchers only, not to a company as a third party. |

| 10 | Of course, we are not claiming that voting for the FDP causally leads to consenting to a data transfer. Our working hypothesis that would have to be substantiated in future work is that the same attitude that makes people vote for the FDP also makes them trust firms not to use people’s data to their disadvantage. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).