Incentive Magnitude Effects in Experimental Games: Bigger is not Necessarily Better

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

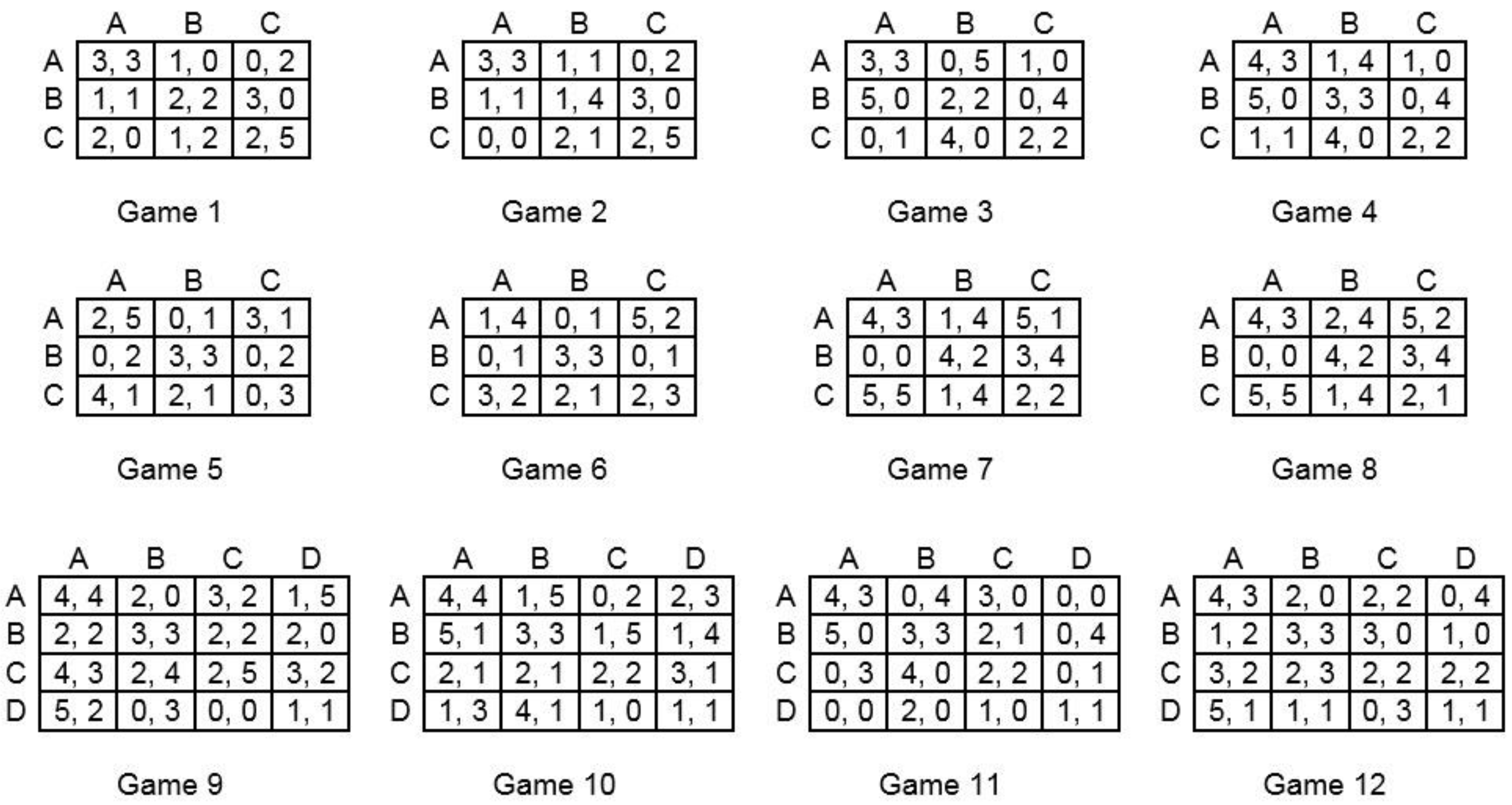

2.2. Design

2.3. Materials

2.4. Procedure

- If you choose A, then:

- If Red chooses A, you will get 3, and Red will get 3

- If Red chooses B, you will get 1, and Red will get 0

- If Red chooses C, you will get 0, and Red will get 2

- (and so on …)

3. Results

3.1. Strategy Choices

3.2. Multiplying Payoffs by 5

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flood, M.M. Some Experimental Games: Research Memorandum RM-789-1; The Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1952; Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_memoranda/2008/RM789-1.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2017).

- Flood, M.M. Some experimental games. Manag. Sci. 1958, 5, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, E.H. An experimental imperfect market. J. Polit. Econ. 1948, 56, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliet, D.; Mulder, L.B.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Reward, punishment, and cooperation: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruitt, D.G.; Kimmel, M.J. Twenty years of experimental gaming: Critique, synthesis, and suggestions for the future. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 1977, 28, 363–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.L. Experimental economics: Induced value theory. Am. Econ. Rev. 1976, 66, 274–279. [Google Scholar]

- Read, D. Monetary incentives, what are they good for? J. Econ. Methodol. 2005, 12, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, A.A. A theorist’s view of experiments. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2001, 45, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C.F.; Hogarth, R.M. The effects of financial incentives in economic experiments: A review and capital-labor-production framework. J. Risk Uncertain. 1999, 19, 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwig, R.; Ortmann, A. Experimental practices in economics: A methodological challenge for psychologists? Behav. Brain Sci. 2001, 24, 383–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardsley, N.; Cubitt, R.; Loomes, G.; Moffatt, P.; Starmer, C.; Sugden, R. Experimental Economics: Rethinking the Rules; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781400831432. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V.L.; Walker, J.M. Monetary rewards and decision costs in experimental economics. Econ. Inq. 1993, 31, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, R.; Lipe, M.G. Incentives, effort, and the cognitive processes involved in accounting-related judgments. J. Account. Res. 1992, 30, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellaoui, M.; Kemel, E. Eliciting prospect theory when consequences are measured in time units: “Time is not money”. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 1844–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, S.; Jowett, S. Hypothetical versus real preferences: Results from an opportunistic field experiment. Health Econ. 2010, 19, 1502–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemel, E.; Travers, M. Comparing attitudes towards time and money in experience-based decisions. Theory Decis. 2016, 80, 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühberger, A.; Schulte-Mecklenbeck, M.; Perner, J. Framing decisions: Hypothetical and real. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2002, 89, 1162–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagorio, C.H.; Madden, G.J. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards III: Steady-state assessments, forced-choice trials, and all real rewards. Behav. Process. 2005, 69, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noussair, C.N.; Trautmann, S.T.; van de Kuilen, G. Higher order risk attitudes, demographics, and financial decisions. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2014, 81, 325–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noussair, C.N.; Trautmann, S.T.; van de Kuilen, G.; Vellekoop, N. Risk aversion and religion. J. Risk Uncertain. 2013, 47, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, M.; Weizsäcker, G. Narrow bracketing and dominated choices. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009, 99, 1508–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.; Betsch, C. Explaining heterogeneity in utility functions by individual differences in decision modes. J. Econ. Psychol. 2006, 27, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Gaudecker, H.-M.; van Soest, A.; Wengström, E. Heterogeneity in risky choice behavior in a broad population. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 664–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gneezy, U.; Rustichini, A. Pay enough or don’t pay at all. Q. J. Econ. 2000, 115, 791–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L. Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 18, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Koestner, R.; Ryan, R.M. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 627–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bénabou, R.; Tirole, J. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2003, 70, 489–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, M.G.; Martinsson, P.; Visser, M. Does stake size matter for cooperation and punishment? Econ. Lett. 2008, 99, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, O.; Rand, D.G.; Gal, Y.G. Economic games on the internet: The effect of $1 stakes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagözoğlu, E.; Urhan, U.B. The effect of stake size in experimental bargaining and distribution games: A survey. Group Decis. Negot. 2017, 26, 285–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, A.M.; Pulford, B.D.; Lawrence, C.L. Explaining strategic coordination: Cognitive hierarchy theory, strong Stackelberg reasoning, and team reasoning. Decision 2014, 1, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C.F.; Ho, T.-H.; Chong, J.-K. A cognitive hierarchy model of games. Q. J. Econ. 2004, 119, 861–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacharach, M. Interactive team reasoning: A contribution to the theory of co-operation. Res. Econ. 1999, 53, 117–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, A.M.; Pulford, B.D.; Rose, J. Collective rationality in interactive decisions: Evidence for team reasoning. Acta Psychol. 2008, 128, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugden, R. Thinking as a team: Towards an explanation of nonselfish behaviour. Soc. Philos. Policy 1993, 10, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. The effect of the background risk in a simple chance improving decision model. J. Risk Uncertain. 2008, 36, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubitt, R.P.; Starmer, C.; Sugden, R. On the validity of the random lottery incentive system. Exp. Econ. 1998, 1, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starmer, C.; Sugden, R. Does the random-lottery system elicit true preferences? Am. Econ. Rev. 1991, 81, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Gneezy, U.; Halladay, B. Experimental methods: Pay one or pay all. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2016, 131, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, R.; Hennig-Schmidt, H.; van Winden, F. Emotion at stake—The role of stake size and emotions in a power-to-take game experiment in China with a comparison to Europe. Games 2017, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffatt, P.G. Stochastic choice and the allocation of cognitive effort. Exp. Econ. 2005, 8, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, J.D. Does repetition improve consistency? Exp. Econ. 2001, 4, 5–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control | ×5 | t | df | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||||

| 1 | I chose rows with the aim of avoiding zero payoffs. | 5.64 | 1.54 | 5.89 | 1.62 | −0.784 | 92 | 0.435 |

| 2 | I chose rows by trying to predict or anticipate the most likely choices of the other person and then choosing the rows that would give me the highest payoffs if my predictions were correct. | 4.85 | 2.01 | 4.66 | 2.05 | 0.458 | 92 | 0.648 |

| 3 | I chose rows with the aim of maximizing the total payoff to both me and the other person. | 5.53 | 1.71 | 5.89 | 1.45 | −1.109 | 92 | 0.271 |

| 4 | I chose rows randomly, or with no particular reason in mind. | 1.32 | 0.81 | 1.45 | 1.04 | −0.664 | 92 | 0.508 |

| 5 | I chose rows by working out or estimating the average payoff that I could expect if the other person was equally likely to choose any column, and then choosing the best rows for me on that basis. | 3.94 | 2.03 | 4.49 | 2.14 | −1.288 | 92 | 0.201 |

| 6 | I chose rows with the aim of trying to get higher payoffs than the other person. | 2.98 | 1.99 | 2.79 | 1.93 | 0.473 | 92 | 0.638 |

| 7 | I chose rows with the aim of trying to ensure that the payoffs to me and the other person were the same or equal. | 4.85 | 1.77 | 5.45 | 1.67 | −1.681 | 92 | 0.096 |

| 8 | I chose rows by finding the highest possible payoff available to me in each grid and aiming for that payoff. | 3.91 | 2.02 | 2.74 | 1.85 | 2.931 | 92 | 0.004 |

| 9 | I chose as if the other person could anticipate my choices and they would always pick the best for them, and then I chose the best response for me. | 4.19 | 2.07 | 4.28 | 1.89 | −0.208 | 92 | 0.835 |

| 10 | I chose the best row for myself, pretending that, whatever row I chose, the other person would choose whatever column is best for them. | 3.79 | 1.90 | 4.02 | 2.03 | −0.578 | 92 | 0.565 |

| Games | Modal Choice Control | Modal Choice ×5 | CH Level-1 | CH Level-2 | Strong Stack. | Team Reas. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 × 3 games | ||||||

| 1 | B | A | B | B | A | C |

| 2 | A | A | B | B | A | C |

| 3 | B | B | B | C | C | A |

| 4 | B | B | B | C | C | A |

| 5 | C | B | C | C | B | A |

| 6 | C | C | C | C | B | A |

| 7 | C | C | A | B | C | C |

| 8 | C | C | A | B | C | C |

| 4 × 4 games | ||||||

| 9 | A | A | C | D | B | A |

| 10 | A | A | B | D | C | A |

| 11 | B | B | B | C | D | A |

| 12 | C | C | C | D | B | A |

| Games | A | B | C | D | χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 × 3 games | |||||||

| 1 (control) | 18 | 19 | 10 | 0.733 | 2 | 0.693 | |

| 1 (×5) | 22 | 17 | 8 | ||||

| 2 (control) | 23 | 19 | 5 | 0.048 | 2 | 0.976 | |

| 2 (×5) | 22 | 20 | 5 | ||||

| 3 (control) | 15 | 24 | 8 | 0.737 | 2 | 0.692 | |

| 3 (×5) | 19 | 21 | 7 | ||||

| 4 (control) | 10 | 23 | 14 | 0.173 | 2 | 0.917 | |

| 4 (×5) | 11 | 21 | 15 | ||||

| 5 (control) | 8 | 15 | 24 | 1.550 | 2 | 0.461 | |

| 5 (×5) | 10 | 19 | 18 | ||||

| 6 (control) | 4 | 13 | 30 | 0.412 | 2 | 0.814 | |

| 6 (×5) | 5 | 15 | 27 | ||||

| 7 (control) | 14 | 2 | 31 | 0.623 | 2 | 0.733 | |

| 7 (×5) | 11 | 3 | 33 | ||||

| 8 (control) | 20 | 2 | 25 | 0.520 | 2 | 0.771 | |

| 8 (×5) | 17 | 3 | 27 | ||||

| 4 × 4 games | |||||||

| 9 (control) | 22 | 2 | 17 | 6 | 4.206 | 3 | 0.240 |

| 9 (×5) | 20 | 6 | 19 | 2 | |||

| 10 (control) | 28 | 13 | 6 | 0 | 4.533 | 2 | 0.104 |

| 10 (×5) | 20 | 13 | 14 | 0 | |||

| 11 (control) | 4 | 36 | 0 | 7 | 0.938 | 2 | 0.626 |

| 11 (×5) | 4 | 39 | 0 | 4 | |||

| 12 (control) | 11 | 9 | 22 | 5 | 1.016 | 3 | 0.797 |

| 12 (×5) | 8 | 12 | 21 | 6 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pulford, B.D.; Colman, A.M.; Loomes, G. Incentive Magnitude Effects in Experimental Games: Bigger is not Necessarily Better. Games 2018, 9, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9010004

Pulford BD, Colman AM, Loomes G. Incentive Magnitude Effects in Experimental Games: Bigger is not Necessarily Better. Games. 2018; 9(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9010004

Chicago/Turabian StylePulford, Briony D., Andrew M. Colman, and Graham Loomes. 2018. "Incentive Magnitude Effects in Experimental Games: Bigger is not Necessarily Better" Games 9, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9010004

APA StylePulford, B. D., Colman, A. M., & Loomes, G. (2018). Incentive Magnitude Effects in Experimental Games: Bigger is not Necessarily Better. Games, 9(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9010004