Security Investment, Hacking, and Information Sharing between Firms and between Hackers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Early and General Literature

1.3. Information Sharing among Firms

1.4. Information Sharing among Hackers

1.5. This Paper’s Contribution

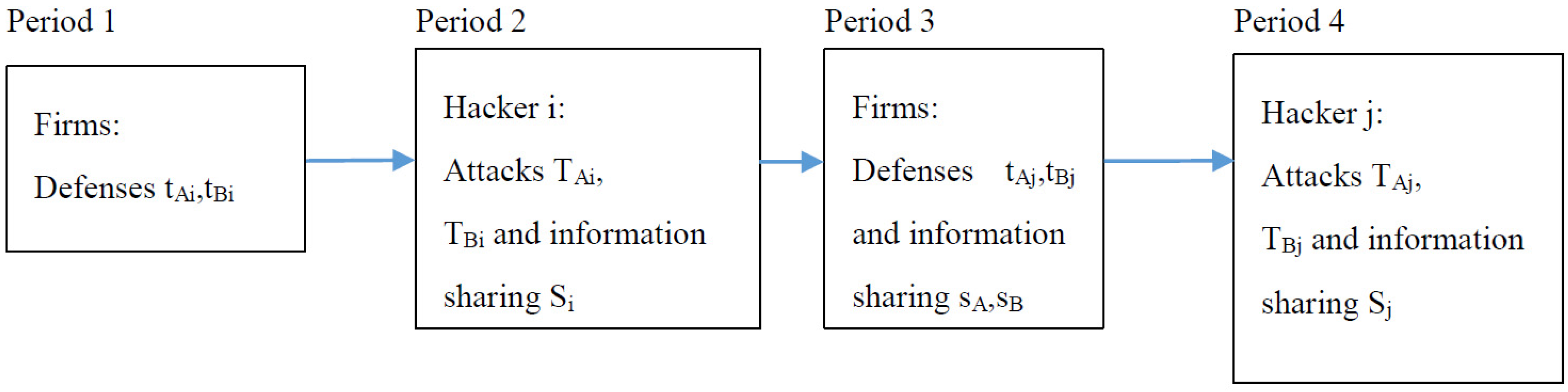

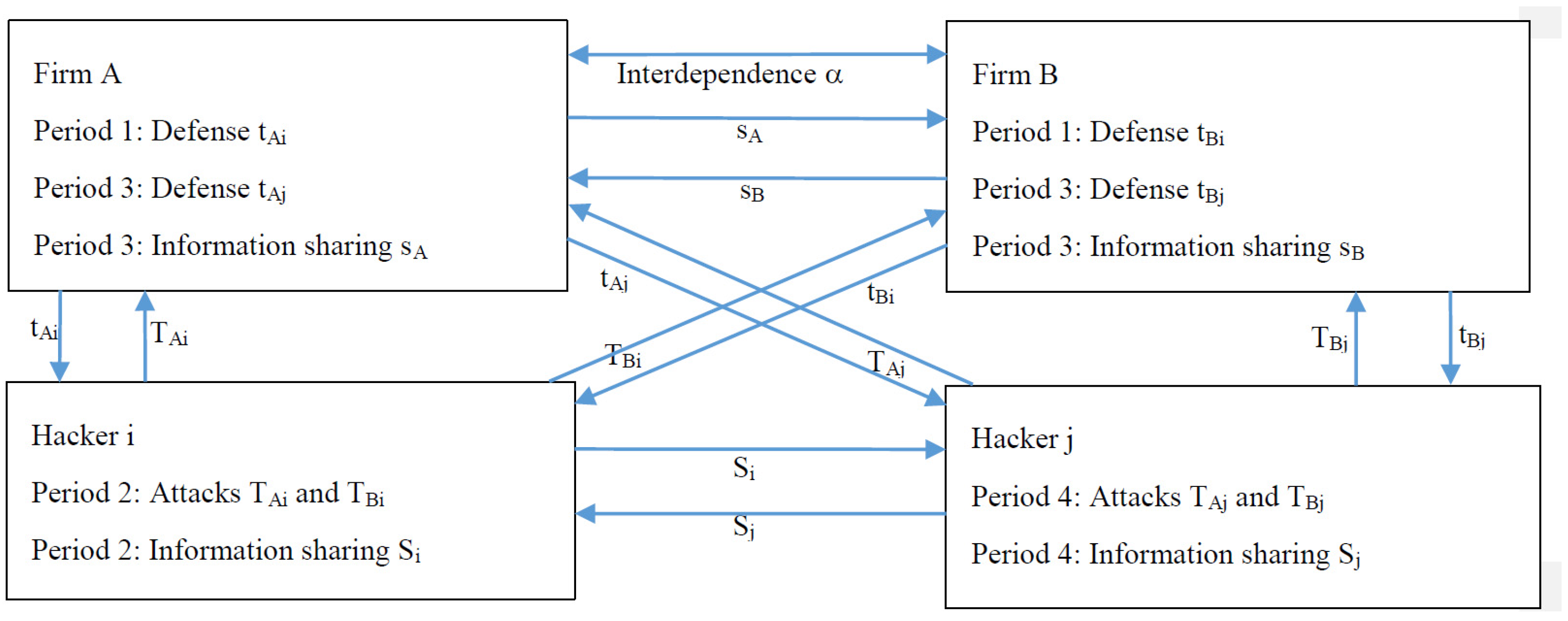

2. Model

3. Analysis

3.1. Interior Solution

3.2. Corner Solution When Hacker i Is Deterred

3.3. Corner Solution When Hacker j Is Deterred

3.4. Corner Solution When Hacker i Shares a Maximum Amount of Information

3.5. Some Special Cases of Advantage for Hackers i and j

4. Policy and Managerial Implications

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Interior Solution

Appendix A.2. Mutual Reaction between Hacker i and Each Firm in the First Attack

Appendix A.3. Corner Solution When Hacker i Is Deterred

Appendix A.4. Corner Solution When Hacker j Is Deterred

References

- Kampanakis, P. Security automation and threat information-sharing options. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2014, 12, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novshek, W.; Sonnenschein, H. Fulfilled expectations cournot duopoly with information acquisition and release. Bell J. Econ. 1982, 13, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal-Or, E. Information sharing in oligopoly. Econometrica 1985, 53, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, C. Exchange of cost information in oligopoly. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1986, 53, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A.J. Trade associations as information exchange mechanisms. RAND J. Econ. 1988, 19, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, X. Trade association disclosure rules, incentives to share information, and welfare. RAND J. Econ. 1990, 21, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremonini, M.; Nizovtsev, D. Risks and benefits of signaling information system characteristics to strategic attackers. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 26, 241–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fultz, N.; Grossklags, J. Blue versus red: Towards a model of distributed security attacks. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Accra Beach, Barbados, 23–26 February 2009; Springer: Christ Church, Barbados, 2009; pp. 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Herley, C. Small world: Collisions among attackers in a finite population. In Proceedings of the 12th Workshop on the Economics of Information Security (WEIS), Washington, DC, USA, 11–12 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y. The institutionalization of hacking practices. Ubiquity 2003, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvari, H.; Abozinadah, E.; Mbaziira, A.; Mccoy, D. Constructing and analyzing criminal networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), San Jose, CA, USA, 17–18 May 2014; pp. 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- August, T.; Niculescu, M.F.; Shin, H. Cloud implications on software network structure and security risks. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Lahiri, A.; Zhang, G. Quality competition and market segmentation in the security software market. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 589–606. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, D.; Lahiri, A.; Zhang, G. Hacker behavior, network effects, and the security software market. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreth, M.; Shor, M. The impact of malicious agents on the enterprise software industry. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 595–612. [Google Scholar]

- Chul Ho, L.; Xianjun, G.; Raghunathan, S. Contracting information security in the presence of double moral hazard. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 295–311. [Google Scholar]

- Ransbotham, S.; Mitra, S. Choice and chance: A conceptual model of paths to information security compromise. Inf. Syst. Res. 2009, 20, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.A.; Loeb, M.P.; Lucyshyn, W. Sharing information on computer systems security: An economic analysis. J. Account. Public Policy 2003, 22, 461–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal-Or, E.; Ghose, A. The economic incentives for sharing security information. Inf. Syst. Res. 2005, 16, 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausken, K. Security investment and information sharing for defenders and attackers of information assets and networks. In Information Assurance, Security and Privacy Services, Handbooks in Information Systems; Rao, H.R., Upadhyaya, S.J., Eds.; Emerald Group Pub Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 4, pp. 503–534. [Google Scholar]

- Hausken, K. Information sharing among firms and cyber attacks. J. Account. Public Policy 2007, 26, 639–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhong, W.; Mei, S. A game-theoretic analysis of information sharing and security investment for complementary firms. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2014, 65, 1682–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ji, Y.; Mookerjee, V. Knowledge sharing and investment decisions in information security. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 52, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinder, J.; Drabwell, P. Cyber security: A critical examination of information sharing versus data sensitivity issues for organisations at risk of cyber attack. J. Bus. Contin. Emerg. Plan. 2013, 7, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Choras, M. Comprehensive approach to information sharing for increased network security and survivability. Cybern. Syst. 2013, 44, 550–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamjidyamcholo, A.; Bin Baba, M.S.; Tamjid, H.; Gholipour, R. Information security—Professional perceptions of knowledge-sharing intention under self-efficacy, trust, reciprocity, and shared-language. Comput. Educ. 2013, 68, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha Flores, W.; Antonsen, E.; Ekstedt, M. Information security knowledge sharing in organizations: Investigating the effect of behavioral information security governance and national culture. Comput. Secur. 2014, 43, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamjidyamcholo, A.; Bin Baba, M.S.; Shuib, N.L.M.; Rohani, V.A. Evaluation model for knowledge sharing in information security professional virtual community. Comput. Secur. 2014, 43, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Png, I.P.L.; Wang, Q.-H. Information security: Facilitating user precautions vis-à-vis enforcement against attackers. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 26, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.P.; Fershtman, C.; Gandal, N. Network security: Vulnerabilities and disclosure policy. J. Ind. Econ. 2010, 58, 868–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizovtsev, D.; Thursby, M. To disclose or not? An analysis of software user behavior. Inf. Econ. Policy 2007, 19, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Krishnan, R.; Telang, R.; Yang, Y. An empirical analysis of software vendors’ patch release behavior: Impact of vulnerability disclosure. Inf. Syst. Res. 2010, 21, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temizkan, O.; Kumar, R.L.; Park, S.; Subramaniam, C. Patch release behaviors of software vendors in response to vulnerabilities: An empirical analysis. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 28, 305–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusoglu, H.; Mishra, B.; Raghunathan, S. The value of intrusion detection systems in information technology security architecture. Inf. Syst. Res. 2005, 16, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; Clayton, R.; Anderson, R. The economics of online crime. J. Econ. Perspect. 2009, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skopik, F.; Settanni, G.; Fiedler, R. A problem shared is a problem halved: A survey on the dimensions of collective cyber defense through security information sharing. Comput. Secur. 2016, 60, 154–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausken, K. A strategic analysis of information sharing among cyber attackers. J. Inf. Syst. Technol. Manag. 2015, 12, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausken, K. Information sharing among cyber hackers in successive attacks. Int. Game Theory Rev. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, E.S. The Cathedral & the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, C. A Look at the Security of the Open Source Development Model; Technical Report; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brunker, M. Hackers: Knights-Errant or Knaves? NBCNews. 1998. Available online: http://msnbc.msn.com/id/3078783 (accessed on 24 May 2017).

- Simon, H. The Sciences of the Artificial; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer, J. Anarchy and its breakdown. J. Political Econ. 1995, 103, 26–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullock, G. The welfare costs of tariffs, monopolies, and theft. West. Econ. J. 1967, 5, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salop, S.C.; Scheffman, D.T. Raising rivals’ costs. Am. Econ. Rev. 1983, 73, 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Hausken, K. Production and conflict models versus rent-seeking models. Public Choice 2005, 123, 59–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullock, G. Efficient rent-seeking. In Toward a Theory of the Rent-Seeking Society; Buchanan, J.M., Tollison, R.D., Tullock, G., Eds.; Texas A. & M. University Press: College Station, TX, USA, 1980; pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kunreuther, H.; Heal, G. Interdependent security. J. Risk Uncertain. 2003, 26, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausken, K. Income, interdependence, and substitution effects affecting incentives for security investment. J. Account. Public Policy 2006, 25, 629–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levins, R. The strategy of model building in population biology. Am. Sci. 1966, 54, 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Levins, R.; Lewontin, R. The Dialectical Biologist; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

| tQi | Firm Q’s defense against hacker i in period 1, Q = A,B | iv |

| tQj | Firm Q’s defense against hacker j in period 3, Q = A,B | iv |

| sQ | Firm Q’s information sharing with the other firm in period 3, Q = A,B | iv |

| TQi | Hacker i’s attack against firm Q in period 2, Q = A,B | iv |

| TQj | Hacker j’s attack against firm Q in period 4, Q = A,B | iv |

| Si | Hacker i’s information sharing with hacker j in period 2 | iv |

| uQ | Firm Q’s expected utility, Q = A,B | dv |

| Uk | Hacker k’s expected utility, k = i,j | dv |

| Sj | Hacker j’s information sharing with hacker i in period 4 | p |

| vk | Each firm’s asset value before hacker k’s attack, k = i,j | p |

| Vk | Hacker k’s valuation of each firm before its attack, k = i,j | p |

| ck | Each firm’s unit defense cost before hacker k’s attack, k = i,j | p |

| Ck | Hacker k’s unit attack cost, k = i,j | p |

| α | Interdependence between the firms | p |

| γ | Information sharing effectiveness between firms | p |

| ϕ1 | Each firm’s unit cost (inefficiency) of own information leakage | p |

| ϕ2 | Each firm’s unit benefit (efficiency) of the other firm’s information leakage | p |

| ϕ3 | Each firm’s unit benefit (efficiency) of joint information leakage | p |

| Гk | Hacker k’s information sharing effectiveness with the other hacker, k = i,j | p |

| Ʌk | Hacker k’s utilization of joint information sharing, k = i,j | p |

| Ωk | Hacker k’s reputation gain parameter, k = i,j | p |

| ti | Ti | Si | tj | s | Tj | Ui | Uj | Ui + Uj | u | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ci = Cj = 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.208 | 0.2 | 0.125 | 0.625 | 0.832 | 1.457 | 0.523 |

| Ci = 1, Cj = 3/2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.354 | 0.2 | 0.0625 | 0.531 | 0.349 | 0.881 | 0.603 |

| Ci = 3/2, Cj = 1 | 0.375 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.208 | 0.2 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.832 | 1.082 | 0.648 |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hausken, K. Security Investment, Hacking, and Information Sharing between Firms and between Hackers. Games 2017, 8, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/g8020023

Hausken K. Security Investment, Hacking, and Information Sharing between Firms and between Hackers. Games. 2017; 8(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/g8020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleHausken, Kjell. 2017. "Security Investment, Hacking, and Information Sharing between Firms and between Hackers" Games 8, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/g8020023

APA StyleHausken, K. (2017). Security Investment, Hacking, and Information Sharing between Firms and between Hackers. Games, 8(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/g8020023