An Equilibrium Analysis of Knaster’s Fair Division Procedure

Abstract

:1. Introduction

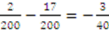

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . The heirs have an equal clam to the objects and are looking to “ fairly” divide these items using Knaster’s procedure. In particular, each heir submits a bid for each item. In the table below, we display bid vectors for the three heirs, the sum of these bids (or total reported value), and each bidder’s initial fair share—i.e.,

. The heirs have an equal clam to the objects and are looking to “ fairly” divide these items using Knaster’s procedure. In particular, each heir submits a bid for each item. In the table below, we display bid vectors for the three heirs, the sum of these bids (or total reported value), and each bidder’s initial fair share—i.e.,  of their total reported value.

of their total reported value.

receives

receives  , heir

, heir  receives

receives  , and heir

, and heir  receives items

receives items  and

and  . These items received create value for the recipient. The amount of value created above the initial fair share for the recipient is the bidder’s initial excess valuation. If we add up the initial excess values for the three heirs we get surplus. In this example, the surplus is 6000.

. These items received create value for the recipient. The amount of value created above the initial fair share for the recipient is the bidder’s initial excess valuation. If we add up the initial excess values for the three heirs we get surplus. In this example, the surplus is 6000.

ends up with item 1 and pays $3700 to compensate the other two heirs,

ends up with item 1 and pays $3700 to compensate the other two heirs,  gets item 4 and receives $2700,

gets item 4 and receives $2700,  receives items

receives items  and

and  and receives $1000. By construction, the side payment made by

and receives $1000. By construction, the side payment made by  balances with the amounts paid to

balances with the amounts paid to  and

and  .

. ’s side payment (compensation) increases from to $2700 to $3900, which is a clear improvement for

’s side payment (compensation) increases from to $2700 to $3900, which is a clear improvement for  . Kuhn (1967) provides a similar example in his analysis of Knaster’s procedure and concludes by saying,

. Kuhn (1967) provides a similar example in his analysis of Knaster’s procedure and concludes by saying,

“ The numbers in this example have been chosen only to exhibit the advantages that can accrue to a player who falsely portrays his own valuations with a knowledge of the other player’s true valuations. It points up a clear need for an analysis of the strategic opportunities of this situation.”

2. Knaster’s Fair Division Procedure

be a set of

be a set of  unrelated items to be allocated among

unrelated items to be allocated among  heirs, whom we shall henceforth refer to as players. Each player

heirs, whom we shall henceforth refer to as players. Each player  assigns the value

assigns the value  to item

to item  , for

, for  . The

. The  private values for each item

private values for each item  are independently distributed according to cumulative distribution function

are independently distributed according to cumulative distribution function  with support

with support  , where the probability density function of

, where the probability density function of  by

by  Individual values are private, but the distribution function for each item is known to all players. Last, since objects are unrelated, the value to a player of receiving multiple items is simply the sum of each item’s value.

Individual values are private, but the distribution function for each item is known to all players. Last, since objects are unrelated, the value to a player of receiving multiple items is simply the sum of each item’s value. to a mediator who awards each item to the high bidder. Thus, player

to a mediator who awards each item to the high bidder. Thus, player  is awarded item

is awarded item  if

if  .7 Next, side payments are computed for each item

.7 Next, side payments are computed for each item  as follows:

as follows:

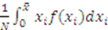

- First, each player

’s initial fair share of item

(defined as

-th of their reported value) is computed—i.e.,

- Second, surplus value for unit

(defined as the difference between the high bid and the average bid) is computed—i.e.,

- Third, a player

’s adjusted fair share is computed from the bids. This is the player’s initial fair share of item

plus an even share of the surplus—i.e.,

- Last, player

’s side payment for item

is their reported value received (if they win the item) minus their adjusted fair share—i.e.,

It is easy to verify that.8

’s payoff for the

’s payoff for the  -th item as a function of submitted bids

-th item as a function of submitted bids  is therefore

is therefore

.

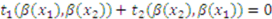

.3. Equilibrium

players. In this section, we find the Bayes–Nash equilibrium for this induced game in symmetric and increasing bidding strategies.

players. In this section, we find the Bayes–Nash equilibrium for this induced game in symmetric and increasing bidding strategies.3.1. Knaster’s Procedure with a Single Object

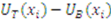

follow the symmetric and increasing strategy

follow the symmetric and increasing strategy  . We consider player 1’s best response problem. Player 1 wins the object if he has the high bid—i.e.,

. We consider player 1’s best response problem. Player 1 wins the object if he has the high bid—i.e.,

. He receives compensation if one of the other players is the high bidder. For instance, Player 2 wins if

. He receives compensation if one of the other players is the high bidder. For instance, Player 2 wins if  ,

,  ,

,  , ...., and

, ...., and  . It is convenient to define the following functions:

. It is convenient to define the following functions:

to maximize his expected payoff—i.e., to solve:

to maximize his expected payoff—i.e., to solve:

is symmetric in its last

is symmetric in its last  arguments and the partial derivative of

arguments and the partial derivative of  is

is

, which, after inputting into (1), combining terms and simplifying, yields:

, which, after inputting into (1), combining terms and simplifying, yields:

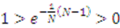

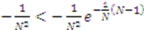

is used to solve the differential equation. However, in Knaster’s auction, this condition is not optimal. Fortunately, there is a unique value

is used to solve the differential equation. However, in Knaster’s auction, this condition is not optimal. Fortunately, there is a unique value  such that

such that  . At this value, the differential equation reduces to the expression

. At this value, the differential equation reduces to the expression  . This is our boundary condition. The solution to Equation (2) is found to be

. This is our boundary condition. The solution to Equation (2) is found to be

is defined such that

is defined such that  .9 It remains to show that strategy profile where every player follows (3) forms a Bayes–Nash equilibrium.

.9 It remains to show that strategy profile where every player follows (3) forms a Bayes–Nash equilibrium. players and one object are given by (3).

players and one object are given by (3).  is an equilibrium. First, it is easily checked that the bidding strategy

is an equilibrium. First, it is easily checked that the bidding strategy  is increasing and continuous. Second, a bidder will never want to bid above

is increasing and continuous. Second, a bidder will never want to bid above  or below

or below  . Bidder 1, for instance, should not submit a bid

. Bidder 1, for instance, should not submit a bid

. A bid equal to

. A bid equal to  wins the item with probability one, thus increasing one’s bid only decreases bidder 1’s expected payoff. Similarly, Bidder 1 should not submit a bid

wins the item with probability one, thus increasing one’s bid only decreases bidder 1’s expected payoff. Similarly, Bidder 1 should not submit a bid

. A bid equal to

. A bid equal to  is guaranteed to lose the item with probability one (but win the compensation), so decreasing one’s bid only decreases 1’s expected payoff since it lowers the compensation. Finally, the expected payoff of bidder 1 whose type is

is guaranteed to lose the item with probability one (but win the compensation), so decreasing one’s bid only decreases 1’s expected payoff since it lowers the compensation. Finally, the expected payoff of bidder 1 whose type is  but bids as if his type were

but bids as if his type were  is

is

and simplifying the resulting expression yields:

and simplifying the resulting expression yields:

we have

we have

, then

, then  . If

. If  , then

, then  . Hence,

. Hence,  is maximized at

is maximized at  . Therefore bidding truthfully according to

. Therefore bidding truthfully according to  is a best response.

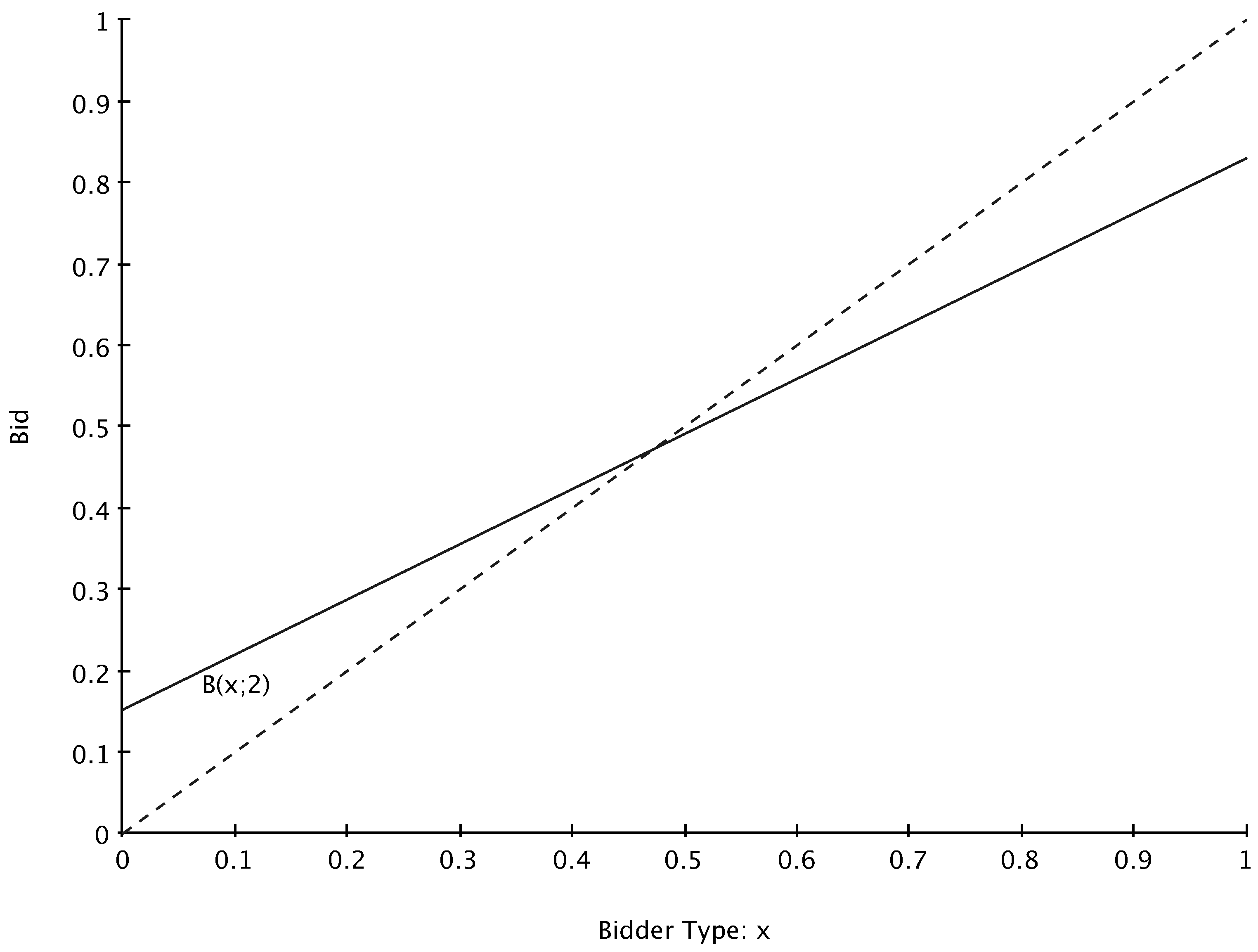

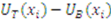

is a best response. and each player

and each player  ’s private value is distributed according to the uniform distribution—i.e.,

’s private value is distributed according to the uniform distribution—i.e.,  for

for  and

and  , then the equilibrium bidding strategy for each player is given by

, then the equilibrium bidding strategy for each player is given by  .10

.10 ), truth telling at

), truth telling at  , and for a player to shade his bid when more likely to win the item and less likely to earn compensation (i.e.,

, and for a player to shade his bid when more likely to win the item and less likely to earn compensation (i.e.,  ).

).

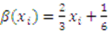

3.2. Multiple Objects

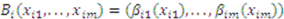

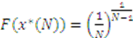

players and multiple objects are given by the vector valued bid function

players and multiple objects are given by the vector valued bid function  , where for

, where for  ,

,  is defined as

is defined as

is defined as the

is defined as the  such that

such that  .

. 4. Welfare and Comparative Statics

-th of the item’s value. However, in equilibrium, bidders typically do not report truthfully. We now check to see if this behavior has welfare consequences.11

-th of the item’s value. However, in equilibrium, bidders typically do not report truthfully. We now check to see if this behavior has welfare consequences.11 be an allocation rule—i.e., a function that assigns to each realization of types a specific allocation, then the following properties are of interest:

be an allocation rule—i.e., a function that assigns to each realization of types a specific allocation, then the following properties are of interest: is ex-post efficient if, for each realization of types, the object in the allocation prescribed is assigned to the player with the highest realized type for that object.

is ex-post efficient if, for each realization of types, the object in the allocation prescribed is assigned to the player with the highest realized type for that object.  is ex-post proportional if, for each realization of types, after the allocation rule has been applied, each player

is ex-post proportional if, for each realization of types, after the allocation rule has been applied, each player  with realized type

with realized type  gets a utility of at least

gets a utility of at least  .

.  is ex-ante proportional if, prior to observing types, each player

is ex-ante proportional if, prior to observing types, each player  ’s expected utility from his part of the allocation rule is greater than

’s expected utility from his part of the allocation rule is greater than  .

.  , where the

, where the  type always prefers the truth telling outcome. The reason is intuitive. This player’s bid in equilibrium is his true value—i.e.,

type always prefers the truth telling outcome. The reason is intuitive. This player’s bid in equilibrium is his true value—i.e.,  . At the Bayes–Nash equilibrium, relative to the truth telling outcome, the

. At the Bayes–Nash equilibrium, relative to the truth telling outcome, the  player wins the object with the same probability, has to pay more in compensation if he wins (since types lower than

player wins the object with the same probability, has to pay more in compensation if he wins (since types lower than  bid above their value), and receives less in compensation if he loses (since types above

bid above their value), and receives less in compensation if he loses (since types above  bid below their value).13 In contrast, low and high types, relative to the truth telling outcome, are better off at the equilibrium outcome.

bid below their value).13 In contrast, low and high types, relative to the truth telling outcome, are better off at the equilibrium outcome. in the truth telling and equilibrium outcomes by

in the truth telling and equilibrium outcomes by  and

and  respectively. Specifically, we show that, on average, there is no difference in the truth telling outcome and the equilibrium outcome. Since the truth telling outcome is known to be proportional, the expectation is that the equilibrium allocation must also be proportional.

respectively. Specifically, we show that, on average, there is no difference in the truth telling outcome and the equilibrium outcome. Since the truth telling outcome is known to be proportional, the expectation is that the equilibrium allocation must also be proportional.

, the general case is similar and is left to the reader. Since the probability of winning the item is the same in equilibrium as in truth telling, the expected difference in

, the general case is similar and is left to the reader. Since the probability of winning the item is the same in equilibrium as in truth telling, the expected difference in  is just the expected difference in the side payments. By design, the transfers always sum to zero regardless of whether we are at the Bayes–Nash equilibrium or the truth telling outcome—i.e.,

is just the expected difference in the side payments. By design, the transfers always sum to zero regardless of whether we are at the Bayes–Nash equilibrium or the truth telling outcome—i.e.,  and

and  . Thus,

. Thus,

is symmetric—i.e.,

is symmetric—i.e.,  . So, the above equality can be re-written as:

. So, the above equality can be re-written as:

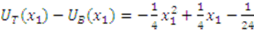

when types are uniformly distributed over the interval

when types are uniformly distributed over the interval  and there are only two bidders. Using the bidding strategies computed in Example 1, this difference simplifies to

and there are only two bidders. Using the bidding strategies computed in Example 1, this difference simplifies to  . From this expression we can see that high types and low types both prefer the outcome under strategic behavior whereas middle types prefer the outcome under truth telling. The expression is maximized at

. From this expression we can see that high types and low types both prefer the outcome under strategic behavior whereas middle types prefer the outcome under truth telling. The expression is maximized at  . In addition, the expected difference is

. In addition, the expected difference is

and there are only two bidders. Specifically, let Player 1 have the type

and there are only two bidders. Specifically, let Player 1 have the type  and Player 2 have the type

and Player 2 have the type  . The symmetric equilibrium bid function, as given in Example 1, for each player

. The symmetric equilibrium bid function, as given in Example 1, for each player  is

is  . So, Player 1’s bid is

. So, Player 1’s bid is  and Player 2’s bid is

and Player 2’s bid is  . Therefore, Player 1 wins the object and pays Player 2 a compensation of

. Therefore, Player 1 wins the object and pays Player 2 a compensation of  . The outcome results in a profit of

. The outcome results in a profit of  , which is worse than the ex-post proportional outcome for Player 1 of

, which is worse than the ex-post proportional outcome for Player 1 of

line as

line as  increases. To establish this claim, we demonstrate that the bid of the lowest type player is diverging from the truth as the number of players increases. First, however, we need the following lemma concerning the threshold type.

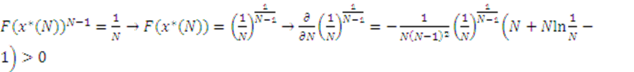

increases. To establish this claim, we demonstrate that the bid of the lowest type player is diverging from the truth as the number of players increases. First, however, we need the following lemma concerning the threshold type. is strictly increasing in

is strictly increasing in  for

for  .

.  if and only if

if and only if  . At

. At  ,

,  . Taking the derivative of the left hand side and right hand side yields

. Taking the derivative of the left hand side and right hand side yields  and

and  respectively. Now

respectively. Now  for

for  , which implies

, which implies  . Thus, the right hand side is decreasing at a slower rate than the left hand side for all

. Thus, the right hand side is decreasing at a slower rate than the left hand side for all  . So,

. So,  for

for  . Hence,

. Hence,  is increasing in

is increasing in  . Now

. Now  is a cdf that , by assumption, is differentiable and strictly increasing. Thus,

is a cdf that , by assumption, is differentiable and strictly increasing. Thus,  has an inverse

has an inverse  that is strictly increasing. Thus,

that is strictly increasing. Thus,  is also increasing in

is also increasing in  .

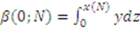

.  line by demonstrating that the bid of the lowest type bidder is moving in the wrong direction.

line by demonstrating that the bid of the lowest type bidder is moving in the wrong direction. , is strictly increasing in

, is strictly increasing in  for

for  .

.  , where

, where  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

by definition of

by definition of  . Now from the chain rule:

. Now from the chain rule:

we have

we have  . Thus, a sufficient condition for

. Thus, a sufficient condition for  to be positive is for

to be positive is for

is less than or equal to

is less than or equal to  we can form a bound on

we can form a bound on  . In particular, the largest

. In particular, the largest  can get is

can get is

.

.

for all

for all  . It follows

. It follows

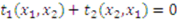

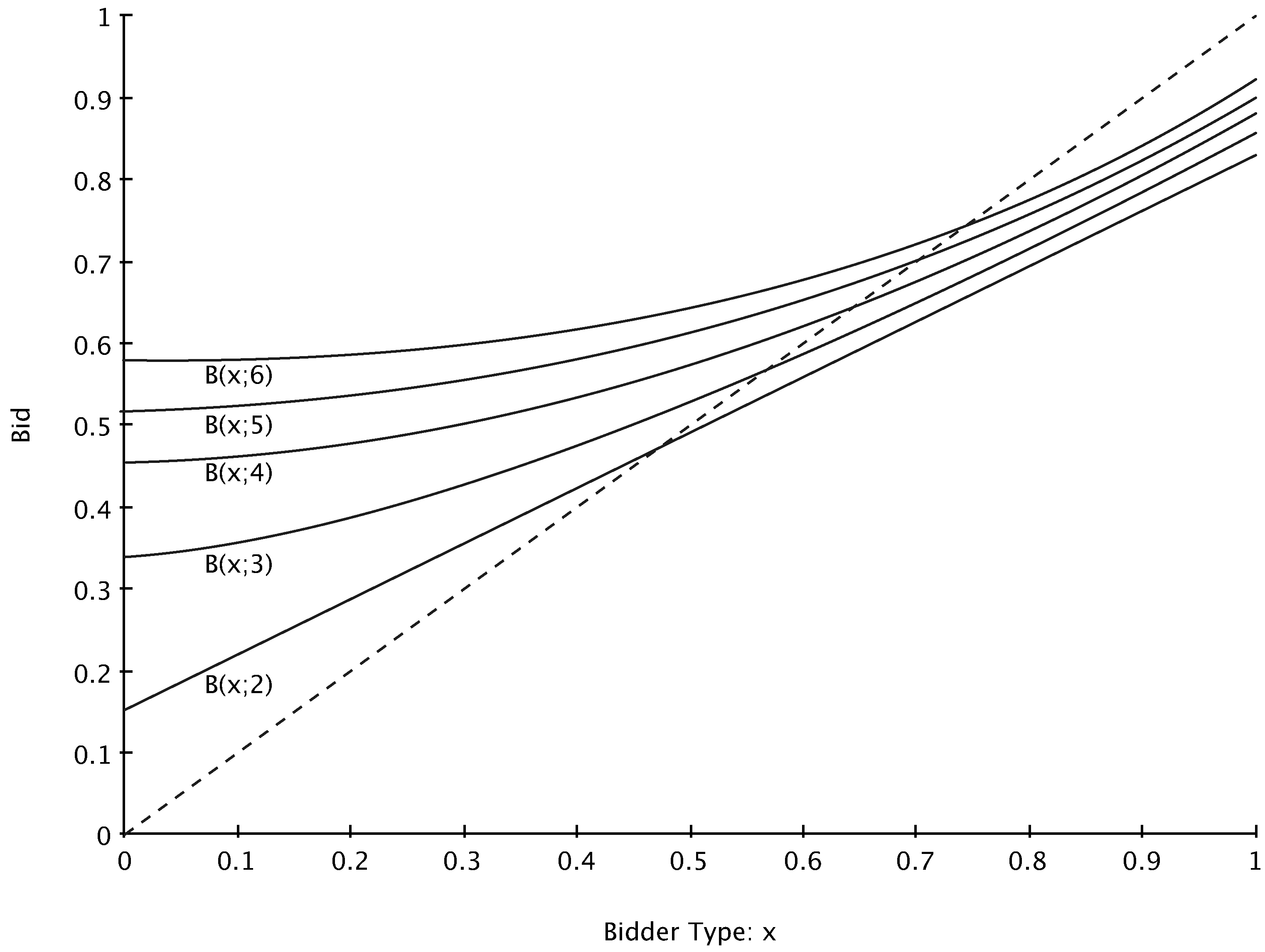

for the uniform distribution case when

for the uniform distribution case when  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . The bid functions displayed are each increasing in

. The bid functions displayed are each increasing in  .

.

5. Discussion

6. Appendix

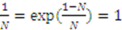

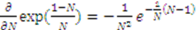

.19 Multiplying both sides of equation (4) by the integrating factor, we have:

.19 Multiplying both sides of equation (4) by the integrating factor, we have:

and

and  .

. , then by definition of absolute value

, then by definition of absolute value  . So, if

. So, if  , then

, then

, then

, then

defines the constant of integration to be

defines the constant of integration to be  for both functions. The equilibrium bid function (3) is found by combining (5) and (9) and inserting the value of

for both functions. The equilibrium bid function (3) is found by combining (5) and (9) and inserting the value of  .

.- 1 This auction first appeared in Steinhaus’s now classic 1948 article on fair division. Steinhaus credits the auction to Knaster. Subsequently, descriptions of the procedure have appeared in Luce and Raiffa (1957), Raiffa (1982), Young (1994), and Brams and Taylor (1996) among others. Kuhn (1967) demoststrates how Knanster’s procedure could be “ discovered” using linear programming.

- 2 Several such auctions are studied in Morgan (2004). In this paper, Morgan analyzes auctions that could be used to “ fairly” dissolve a partnership. He does not consider Knaster’s auction.

- 3 An outcome is proportional if each of the

participating players receive at least

-th of their value for the whole collection of items.

- 4 The following is adopted from Luce and Raiffa (1957). The numbers have been adapted to ease some of the calculations.

- 5 In addition, when

the procedure generates an envy-free allocation.

- 6 See Krishna (2010) for an introduction to auction theory.

- 7 Ties are broken via random assignment.

- 8 Written out, the side payment rule is:

- 9 The steps used to solve equation (2) are provided in the Appendix.

- 10 This is easy to check using equation (2).

- 11 For notational simplicity, our results will be for the one item case. The generalization is straightforward and left to the reader.

- 12 There is also a case where players evaluate the outcome when they know their type, but not the types of the other players (i.e., interim).

- 13 It straightforward to verify that, when

, the difference

is maximized at

.

- 14 For

, when values are uniformly distributed over the interval

, it is straightforward to verify that Knaster’s procedure is interim proportional. However, it is unknown whether this is true in general.

- 15 Proportional allocations satisfy a basic notion of fairness, but stronger concepts have been developed since Steinhaus’s paper. Concepts such as envy-freeness, egalitarian, consistency, population monotonicity, and transparent inequity have all been studied in the fair division literature. See, for instance, Varian (1974), Crawford (1977), Crawford and Heller (1979), Crawford (1980), Demange (1984), Takenuma and Thomson (1993), Moulin (1990b), and Alkan, Demange, and Gale (1991). Young (1994) and Moulin (1988, 1990a, and 2003) survey this large literature.

- 16 Also related is Segal and Whinston (2011) who provide general conditions under which efficient bargaining is possible.

- 17 See Krishna, Chapter 5, for a streamlined discussion of this result.

- 18 There is a large body of work on fair division mechanisms presented throughout the mathematics, economics, and political science literature. For instance, the problem of how to fairly divide a cake has generated a significant body of interest and can be applied to both divisible good and indivisible good allocation problems. Introductions to this cake cutting literature can be found in Brams and Taylor (1996), Robertson and Webb (1998), or Su (1999).

- 19 In particular, our integrating factor

is found by solving the differential equation

We do not need the most general solution to this differential equation. Hence, we dispense with the arbitrary constant.

References

- Alkan, A.; Demange, G.; Gale, D. Fair allocation of indivisible goods and criteria of justice. Econometrica 1991, 59, 1023–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brams, S.; Taylor, A. Fair Division. From Cake Cutting to Dispute Resolution; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brams, S.; Taylor, A. The Win-Win Solution: Guaranteeing Fair Shares to Everybody; W.W. Norton and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Crampton, P.; Gibbons, R.; Klemperer, P. Dissolving a partnership efficiently. Econometrica 1987, 55, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, V. A game of fair division. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1977, 44, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, V.; Heller, P. Fair division with indivisible commodities. J. Econ. Theory 1979, 21, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, V. A self-administered solution of the bargaining problem. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1980, 47, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demange, G. Implementing efficient egalitarian equivalent allocations. Econometrica 1984, 52, 1167–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubins, E.; Spaniers, E. How to cut a cake fairly. Am. Math. Mon. 1961, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, W.; van Damme, E. A comparison of pricing rules for auctions and fair division games. Soc. Choice Welfare 1986, 3, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, V. Auction Theory, 2nd ed; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, H. On games of fair division. In Essays in Mathematical Economics in Honor of Oskar Morgenstern; Shubik, M., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1967; pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Luce, D.; Raiffa, H. Games and Decisions: Introduction and Critical Survey; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- McAfee, R.P. Amicable divorce: Dissolving a Partnership with Simple Mechanisms. J. Econ. Theory 1992, 56, 266–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovanu, B. How to Dissolve a Partnership. J. Inst. Theor. Econ. 2002, 158, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J. Dissolving a partnership (un)fairly. Econ.Theory bf 2004, 24, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, H. Axioms of Cooperative Decision Making; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Moulin, H. Fair Division under joint ownership: Recent results and open problems. Soc. Choice Welfare 1990a, 7, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, H. Uniform externalities: Two axioms for fair allocation. J. Public Econ. 1990b, 43, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, H. Fair Division and Collective Welfare; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Raiffa, H. The Art and Science of Negotiation; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, J.; Webb, W. Cake-Cutting Algorithms: Be Fair if You Can; AK Peters: Natick, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, I.; Whinston, M.D. A simple status quo that assures participation (with application to efficient bargaining). Theor. Econ. 2011, 6, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F. Rental harmony: Sperner’s lemma in fair division. Am. Math. Mon. 1999, 106, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhaus, H. The problem of fair division. Econometrica 1948, 16, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Takenuma, K.; Thomson, W. The fair allocation of an indivisible good when monetary compensations are possible. Math.Soc. Sci. 1993, 25, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varian, H. Equity, envy, and efficiency. J. Econ. Theor. 1974, 9, 63–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, H.P. Equity: In Theory and in Practice; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Essen, M. An Equilibrium Analysis of Knaster’s Fair Division Procedure. Games 2013, 4, 21-37. https://doi.org/10.3390/g4010021

Van Essen M. An Equilibrium Analysis of Knaster’s Fair Division Procedure. Games. 2013; 4(1):21-37. https://doi.org/10.3390/g4010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Essen, Matt. 2013. "An Equilibrium Analysis of Knaster’s Fair Division Procedure" Games 4, no. 1: 21-37. https://doi.org/10.3390/g4010021

APA StyleVan Essen, M. (2013). An Equilibrium Analysis of Knaster’s Fair Division Procedure. Games, 4(1), 21-37. https://doi.org/10.3390/g4010021