1. Introduction

The objective of implementation theory is to study, in a rigorous manner, the relationship between outcomes in a society and the institutions under which those outcomes arise. The outcomes represent the production and allocation of public and private goods and services in a society where each agent has preferences over these outcomes. The institutions are the set of rules under which the allocation is decided and applied (property rights, voting laws and voting rules, constitutions, contract law, etc.). The relationship between institutions and outcomes can be viewed from a perspective of design, and, in this form, is called the theory of mechanism design. The “planner” or the mechanism designer (representative of state, a local collectivity, a region, manager of a firm, etc.) has a goal in mind—to maximize an objective function called social choice correspondence (or rule). This correspondence represents the social objectives that the society or its representatives want to achieve. A difficulty arises in the asymmetry of information between planner and agents. This asymmetric information results because the planner does not know the exact preferences of agents. If, for example, the “options” or outcomes are public goods, the agents will state false preferences in order to participate with lower costs, and once the public property is constructed, they can use it like everyone. In order for the agents to reveal their true preferences, the planner will implement a mechanism (non-cooperative game). It is a way of collecting messages and making a decision; it represents the communication and decision aspects of the organization. This mechanism is a list of messages or “strategy” spaces, and an outcome function mapping messages into allocations, where the strategies of players depend essentially on the preference profiles and the options (or alternatives) set. A social choice correspondence (SCC) is implementable in a given solution concept if the payment with this solution of the game corresponds to the socially desired alternative and vice versa. The planner, thus, hopes to, via this game, get the agents to reveal their sincere preferences.

To characterize the class of the SCCs which are implementable, some conditions on these correspondences should be imposed. Thus, Maskin [

1], as the first to identify an important relationship between implementability and a condition known now as

Maskin monotonicity, demonstrated that any implementable SCC in Nash equilibria must satisfy this condition. However, this condition alone is not sufficient, and so Maskin [

1] gave an additional condition called

no-veto power, thus proving that in a society where at least three agents exist, an SCC is implementable if the conditions of monotonicity and no-veto power hold.

Nevertheless, the problem of implementation theory is that there are important correspondences in economic, social, and political sciences which do not satisfy no-veto power

1. Thus, many authors like Moore and Repullo [

10], Dutta and Sen [

11], Sjöström [

12], Danilov [

13], Yamato [

14], and Ziad [

15,

16], tried to address this problem by providing alternative conditions.

Thomson [

17,

18] applied a certain number of conditions for these previous theoretical results to implement solutions of the problem of fair allocation with

single-peaked preferences. He showed that Maskin’s theorem is silent about the implementability of many solutions which can be implemented by the Yamato’s condition of strong monotonicity. However, he found that this latter condition is not stable under intersection and so he appealed to the algorithm of Sjöm [

12]. More recently, Doghmi and Ziad [

19,

20] provided new sufficient conditions and showed that many solutions can be implemented on the single-peaked preferences domain in an easier way compared to that of the previous conditions in the literature.

This domain of single-peaked preferences has been explored in social choice theory since the work of Black [

21]. In parallel, an inverse configuration to this domain, called

single-dipped preferences, has also been explored in this theory and in many economic applications, but it has never been explored in relation to the problem of implementation theory.

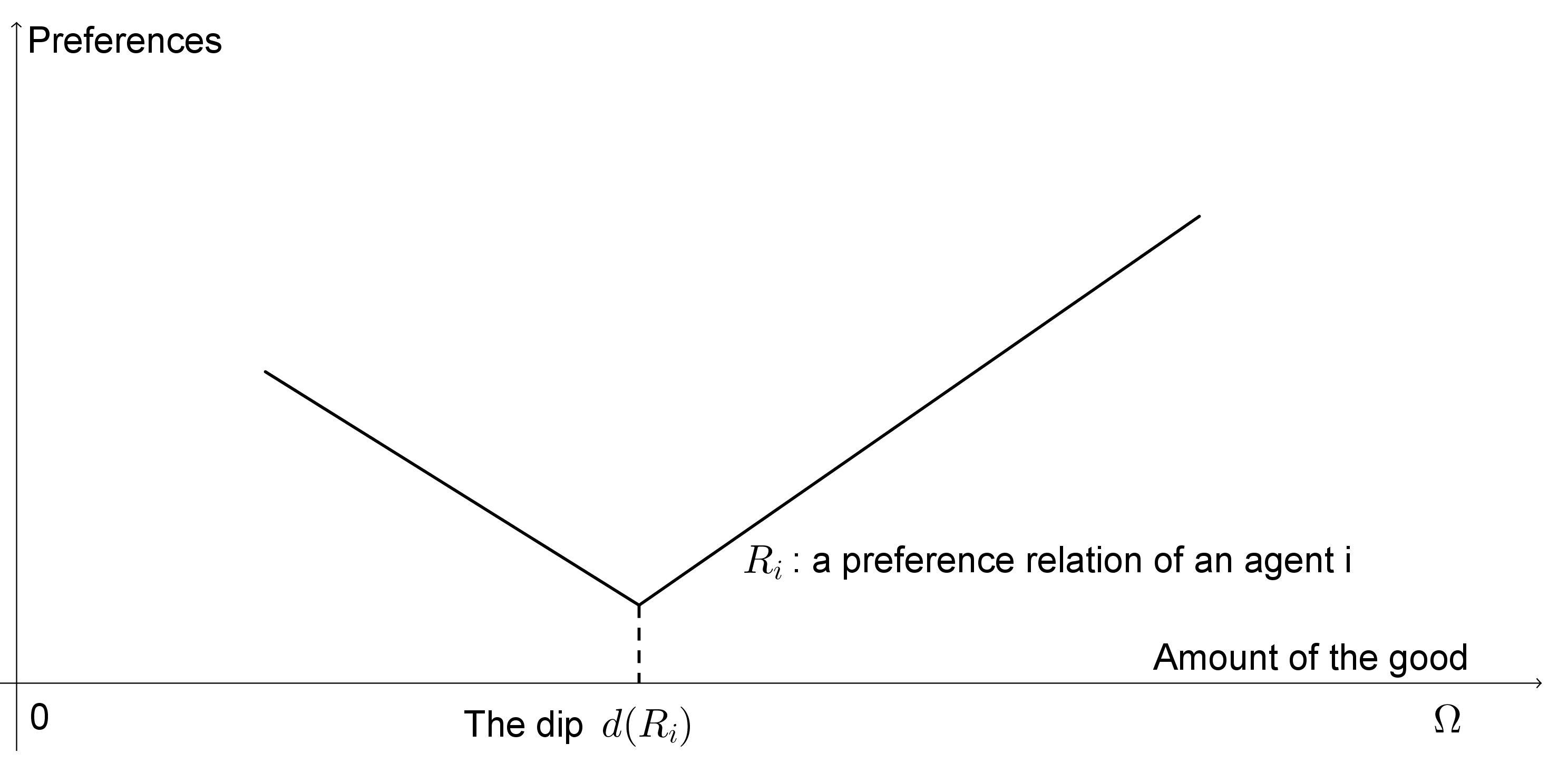

Thus, in this paper, we examine the implementability of solution to the fair division problems when agents have single-dipped preferences. This type of preference requires that each agent has a unique bad alternative. Assuming that there is an amount Ω ∈ ℝ

++ of a certain infinitely divisible good that is to be allocated among a set of

n agents. The preference of each agent

i is represented by a continuous and single-dipped preference relation

Ri over [0, Ω] as illustrated in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Single-dipped preferences.

Figure 1.

Single-dipped preferences.

This type of preference has been introduced by Inada [

22] to study public good situations. It is also explored for private goods areas by Klaus

et al. [

23] to characterize two classes of division rules that satisfy Pareto optimality, strategy-proofness, and replacement-domination proprieties. Klaus [

24,

25] provided two allocation models with single-dipped preferences. In the first model, she considered the problem of allocating an infinitely divisible commodity among agents. She characterized the class of rules that satisfy a whole selection of proprieties. In the second model, she studied the allocation of an indivisible object to a group of agents. Similar to the first model, she characterized the class of rules that satisfy some conditions. Ehlers [

26] studied the problem of allocating an infinitely divisible endowment among a group of agents; he characterized a class of Pareto optimal and coalitionally strategy-proof allocation rules and studied some proprieties of fairness. Manjunath [

27] explored the problem of locating a single public good when preferences of agents are single-dipped, thus providing a characterization of all rules satisfying unanimity and strategy-proofness properties. More recently, Barberà

et al. [

28] were interested in the characterization of the family of all individual and group strategy-proof rules on the domain of single-dipped preferences. They examined the implications of these strategy-proofness requirements on the maximum size of the rules’ range.

In this paper, we study the Nash implementation in an allocation problem with single-dipped preferences. We prove that, with at least three agents, any solution of the problem of fair division can be implemented in Nash equilibria if—and only if—it satisfies Maskin monotonicity. Thus, via this result, the no-veto power condition is dispensed of in this area, and so we implement some well-known correspondences which satisfy Maskin monotonicity but violate the condition of no-veto power.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we introduce notations and definitions. In

Section 3, we state and prove our main result in a domain of the allocation problem with single-dipped preferences, and we justify this result providing some well-known correspondences which satisfy Maskin monotonicity and violate the no-veto power condition.

Section 4 provides our concluding remarks.

2. General Notations and Definitions

Before defining our domain of applications in

Section 3, we provide in this section general notations and definitions in order to present the key concepts of implementation theory. Let

A be a setof alternatives, and let

N = {1, ...,

n} be a set of individuals, with generic element

i. Each individual

i is characterized by a preference relation

Ri defined over

A, which is a complete, transitive, and reflexive relation in some class

ℜi of admissible preference relations. Let

ℜ =

ℜ1 × ... ×

ℜn. An element

R = (

R1, ...,

Rn) ∈ ℜ is a preference profile. The relation

Ri indicates the individual’s

i preference. For

a,

b ∈

A, the notation

aRib means that the individual

i weakly prefers

a to

b. The asymmetrical and symmetrical parts of

Ri are noted respectively by

Pi and ∼

i.

A social choice correspondence (SCC) F is a mapping from ℜ into 2A \{∅}, that associates with every R a non-empty subset of A. For all ℜi ∈ Ri and all a ∈ A, the lower contour set for agent i at alternative a is noted by: L(a, Ri) = {b ∈ A | aRib}. The strict lower contour set and the indifference lower contour set are noted respectively by LS(a, Ri) = {b ∈ A | aPib} and LI(a, Ri) = {b ∈ A | a ∼i b}.

A mechanism (or form game) is given by Γ = (S, g) where S = Πi∈N Si; Si denotes the strategy set of the agent i and g is a function from S to A. The elements of S are denoted by s = (s1,s2, ..., sn) = (si, s−i), where s−i = (s1, ..., si−1, si+1, ..., sn). When s ∈ S and bi ∈ Si, (bi, s−i) = (s1, ..., si−i,bi, si+1, ..., sn) is obtained after replacing si by bi, and g(Si, s−i) is the set of results which agent i can obtain when the other agents choose s−i from S−i = Πj ∈ N, j ≠ iSj.

A Nash equilibrium of the game (Γ,R) is a vector of strategies s ∈ S such that for any i, g(s)Rig(bi, s−i) for all bi ∈ Si, i.e. when the other players choose s−i, the player i cannot deviate from si. Given N(g, R, S) the set of Nash equilibria of the game (Γ,R), a mechanism Γ = (S, g) implements an SCC F in Nash equilibria if for all R ∈ ℜ,F (R) = g(N(g, R, S)).

We say that an SCC F is implementable in Nash equilibria if there is a mechanism which implements it in these equilibria.

A SCC F satisfies unanimity if for any a ∈ A and any R ∈ ℜ, if for any i ∈ N, L(a, Ri) = A, then a ∈ F (R).

Maskin [

1] introduced the following conditions on

F to characterize the SCCs that are implementable in Nash equilibria.

Monotonicity: This condition stipulates that if an alternative a is socially chosen in a profile R, and if the alternatives ranked below a for all agents remain ranked below it (in the large sense) in a new profile R′, then the alternative a must be socially chosen in R′.

A SCC F satisfies monotonicity if for all R, R′ ∈ ℜ, for any a ∈ F (R), if for any i ∈ N, L(a, Ri) ⊆ L(a, R′i), then a ∈ F (R′).

Maskin [

1] proved that any Nash implementable correspondence must satisfy Maskin monotonicity. However, this condition alone is not sufficient. For this, Maskin [

1] gave the following additional condition.

No-veto power: This condition requires that if an alternative is ranked at the top for all agents except one, then this alternative must be socially chosen.

A SCC F satisfies no-veto power if for i, R ∈ ℜ, and a ∈ A, if L(a, Rj) = A for all j ∈ N\{i}, then a ∈ F (R).

Maskin [

1] showed that, with at least three players, any social choice correspondence satisfies Maskin monotonicity, and the no-veto power is thus Nash implementable.

Doghmi and Ziad [

19] reexamined this result by introducing the following new sufficient conditions.

Strict monotonicity: It is a strong version of Maskin monotonicity. A SCC F satisfies strict monotonicity if for all R, R′ ∈ ℜ, for any a ∈ F (R), if for any i ∈ N, LS(a, Ri) ∪{a}⊆ L(a, Ri’), then a ∈ F (R’).

Strict weak no-veto power. It is a weak version of no-veto power. It lies between no-veto power and unanimity. A SCC F satisfies strict weak no-veto power if for i, R ∈ ℜ, and a ∈ F (R), if for R′ ∈ ℜ, b ∈ LS(a, Ri) ⊆ L(b, R′i) and L(b, R′j) = A for all j ∈ N\{i}, then b ∈ F (R′).

Doghmi and Ziad [

19] showed that, in addition to unanimity, strict monotonicity and strict weak no-veto power are sufficient for an SCC

F to be implementable.

3. Applications to Allocation Problem with Single-Dipped Preferences

There is an amount Ω ∈ ℝ

++ of a certain infinitely divisible good that is to be allocated among a set

N = {1, ...,

n} of

n agents. The preference of each agent

i ∈

N is represented by a continuous and single-dipped preference relation

Ri over [0, Ω] (the asymmetrical part is written

Pi and the symmetrical part ∼

i). For all

xi,

yi ∈ [0, Ω],

xiRiyi means that, for the agent

i, to consume a share

xi is as good as to consume the quantity

yi. A feasible allocation for the economy (

R, Ω) is a vector

x ≡ (

xi)

i ∈ N ∈ ℝ

+n such that Σ

i ∈ N xi = Ω and

X is the set of the feasible allocations. We note that the feasible allocations set is

X = [0, Ω] × ... × [0, Ω]. Thus,

L(

x,

Ri) =

X is equivalent to

L(

xi,

Ri) = [0, Ω]. For the set

L(

x,

Ri) =

X,

xRiy for all

y ∈

X implies that

xiRiyi. Thus, the agents’ preferences are defined over individual consumption spaces, not over allocation space. Then the proprieties of implementation theory, presented in general setup in

Section 2, become as follows: A SCC

F satisfies monotonicity if for all

R,

R′ ∈ ℜ, for any

x ∈

F (

R), if for any

i ∈

N,

L(

xi,

Ri) ⊆

L(

xi,

R′i), then

x ∈

F (

R′). A SCC

F satisfies strict monotonicity if for all

R,

R′ ∈ ℜ, for any

x ∈

F (

R), if for any

i ∈

N,

LS(

xi,

Ri) ∪{

xi}⊆

L(

xi,

R′i), then

x ∈

F (

R′). A SCC

F satisfies no-veto power if for

i,

R ∈ ℜ, and

x ∈

X, if

L(

xj,

Rj) = [0, Ω] for all

j ∈

N\{

i}, then

x ∈

F (

R). A SCC

F satisfies strict weak no-veto power if for

i,

R ∈ ℜ,

x,

y ∈

X, and

x ∈

F (

R), if for

R′ ∈ ℜ,

yi ∈

LS(

xi,

Ri) ⊆

L(

yi,

R′i) and

L(

yj,

R′) = [0, Ω] for all

j ∈

N\{

i}, then

y ∈

F (

R′). A SCC

F satisfies unanimity if for any

x ∈

X and any

R ∈ ℜ, if for any

i ∈

N,

L(

xi,

Ri) = [0, Ω], then

x ∈

F (

R). We note that the free disposability of the good is not assumed.

A preference relation Ri is single-dipped if there is a number d(Ri) ∈ [0, Ω] such that for all xi, yi ∈ [0, Ω] if xi < yi ≤ d(Ri) or d(Ri) ≤ yi < xi, then xiPiyi. We call d(Ri) the dip of Ri.

The class of all single-dipped preference relations is represented by ℜsd ⊆ℜ. For R ∈ ℜsd, let d(R) = (d(R1), ..., d(Rn)) be the profile of dips. A single-dipped preference relation Ri ∈ ℜsdi is described by the function ri : [0, Ω] → [0, Ω] which is defined as follows: ri(xi) is the consumption of the agent i on the other side of the dip which is indifferent to xi (if it exists); otherwise, it is 0 or Ω. Formally, if xi ≤ d(Ri), then, ri(xi) ≥ d(Ri) and xi ∼i ri(xi) if such a number exists or ri(xi) = Ω otherwise; if xi ≥ d(Ri), then, ri(xi) ≤ d(Ri) and xi ∼i ri(xi) if such a number exists or ri(xi) = 0 otherwise.

Let us introduce some well-known correspondences.

No-Envy correspondence,

NE, (Foley [

29]). This correspondence selects the feasible allocations for which each agent prefers his own share than the shares of the other agents. It is defined as follows: Let

R ∈ ℜ

sd,

NE(

R) = {

x ∈

X if

xiRixj for each pair {

i,

j}⊆

N}.

Individually Rational Correspondence from Equal Division, Ied: This correspondence selects the feasible allocations for which each agent prefers his own share rather than the average one. It is defined as follows: Let R ∈ ℜsd, Ied(R) = {x ∈ X : xiRi(Ω/n) for all i ∈ N}.

Pareto correspondence, P : This solution selects the feasible allocations which are not weakly dominated by another allocation for all agents and not strictly dominated for at least one agent. It is defined as follows: Let R ∈ ℜsd, P (R) = {x ∈ X : ∄x′ ∈ X such that for all i ∈ N, x′iRixi, and for some i ∈ N, x′iPixi}.

3.1. The Main Result: Robustness of Maskin Monotonicity

As mentioned in

Section 2, Maskin monotonicity is a necessary condition that an SCC must satisfy in order to be Nash implementable. However, Maskin monotonicity alone is not sufficient for implementation. In this subsection, we show that, in the domain of the allocation problem with single-dipped preferences, Maskin monotonicity becomes necessary and sufficient for implementation, and so the no-veto power condition is no longer required. To prove this result, we begin by introducing the following Lemmas.

Lemma 1 Let R, R′ ∈ ℜsd and x, y ∈ X. If the preferences are single-dipped, yi ∈ LS(xi, Ri), and LS(xi, Ri) ⊆ L(yi, R′i), then L(yi, R′i) = [0, Ω].

Proof. Let R, R′ ∈ ℜsd and x, y ∈ X. Since we have yi ∈ LS(xi, Ri), and LS(xi, Ri) ⊆ L(yi, R′i), it is clear from the single-dippedness and the continuity of the preferences that L(yi, R′i) = [0, Ω]. Q.E.D.

Lemma 2 On a single-dipped domain, any non-constant strict monotonic SCC satisfies unanimity.

Proof. We show that any non-constant strict monotonic SCC

F satisfies unanimity. Suppose not; i.e., for all

R,

R′ ∈ ℜ

sd, for any

x ∈

F (

R), if for any

i ∈

N,

LS(

xi,

Ri) ∪{

xi}⊆

L(

xi,

R′i), then

x ∈

F (

R′). But, for any

x ∈

X and any

![Games 04 00038 i001]()

∈ ℜ, for any

i ∈

N, [0, Ω] =

L(

xi,

![Games 04 00038 i001]()

), and

x ∉

F (

![Games 04 00038 i001]()

). We have for all

i ∈

N,

LS(

xi,

Ri) ∪{

xi}⊆ [0, Ω] =

L(

xi,

![Games 04 00038 i001]()

). By strict monotonicity,

x ∈

F (

![Games 04 00038 i001]()

),a contradiction. Q.E.D.

According to Lemmas 1 and 2, we have the following corollary:

Corollary 1 On a single-dipped domain, any non-constant strict monotonic SCC satisfies strict weak no-veto power.

In the following, we show that strict monotonicity, alone, is sufficient for Nash implementation when preferences are single-dipped.

Proposition 1 Let n ≥ 3. In the allocation problem with single-dipped preferences, any SCC satisfying strict monotonicity can be implemented in Nash equilibria.

Proof. By Lemma 2, Corollary 1 and Theorem 1 of Doghmi and Ziad [

19], the proof is completed as required. Q.E.D.

Now, we show that strict monotonicity is not only sufficient, but is also necessary, as long as it becomes equivalent to Maskin monotonicity.

Proposition 2 In the allocation problem with single-dipped preferences, the strict monotonicity condition becomes equivalent to Maskin monotonicity.

Proof. Let R, R′ ∈ ℜsd and x, y ∈ X. Suppose xi ≤ d(Ri) (similar statements can be proved for xi ≥ d(Ri)). i) ⇒, it is clear that LS(xi, Ri) ∪{xi}⊆ L(xi, Ri). Therefore, strict monotonicity implies Maskin monotonicity. ii) ⇐, in this case, suppose that LS(xi, Ri) ∪{xi}⊆ L(xi, R′) (1). It is clear that L(xi, Ri) = LS(xi, Ri) ∪{xi}∪{ri(xi)} if ri(xi) exists (2). From (1) and the continuity of preferences, it is necessary to have ri(xi) ≤ ri′ (xi) (3). Then, (1), (2) and (3) give L(xi, Ri) ⊆ L(xi, R′i) ∀i. Thus, we have the inclusion of Maskin monotonicity. Q.E.D.

Through propositions 1 and 2, we complete the proof of the following theorem which is the main result of the paper.

Theorem 1 : Let n ≥ 3. A SCC in the allocation problem with single-dipped preferences is Nash implementable if and only if it satisfies Maskin monotonicity.

To justify this result, we provide in the next subsection a list of solutions which satisfy Maskin monotonicity, and violate the condition of no-veto power.

3.2. Examples of SCCs satisfying/not satisfying Maskin’s proprieties

In this subsection, we check whether the no-envy correspondence, the individually rational correspondence from equal division, (NE∩Ied) correspondence, (NE∩P) correspondence, and (Ied∩P) correspondence satisfy Maskin’s conditions of monotonicity and no-veto power or not.

3.2.1. Maskin Monotonicity

In the considered examples of SCCs, we begin by examining the implementability of the no-envy correspondence. We provide the following proposition.

Proposition 3 The no-envy correspondence satisfies Maskin monotonicity.

As the no-envy correspondence, the individually rational correspondence from the equal division also satisfies Maskin monotonicity.

Proposition 4 The individually rational correspondence from equal division satisfies Maskin monotonicity.

The proofs of Propositions 3 and 4 are omitted. This is because the no-envy correspondence and the individually rational correspondence from equal division satisfy Maskin monotonicity in the general environment and so it is obvious that this condition is checked for the restricted domain of an allocation problem with single-dipped preferences.

By stability under the intersection of Maskin monotonicity, we give the next proposition.

Proposition 5 The intersection of the no-envy correspondence with the individually rational correspondence from equal division satisfies Maskin monotonicity.

According to Doghmi and Ziad [

5], the Pareto correspondence does not satisfy Maskin monotonicity in the domain of the allocation problem with single-dipped preferences, and is hence not Nash implementable

2. In the following, we examine whether or not some correspondences which intercept the Pareto correspondence satisfy Maskin monotonicity. We begin by studying the intersection of the Pareto correspondence with the no-envy correspondence. We give the following lemma.

Lemma 3 On a single-dipped domain, the intersection of the Pareto correspondence with the no-envy correspondence is not empty.

Proof. We show that for all R ∈ ℜsd, (P ∩ NE)(R) ≠ ∅; i.e., there exists x ∈ X such that x ∈ P (R) and x ∈ NE(R). Suppose not; there exists R ∈ ℜsd, for all x ∈ X, x ∉ P (R) or x ∉ NE(R). Suppose that x ∈ P (R) but x ∉ NE(R). This means that (a) ∄y ∈ X such that for all i ∈ N, yiRixi, and for some i ∈ N, yiPixi, but (b) there exists a pair {i, j}⊆ N such that xiPixi. Assume that for all i ∈ N, xi ≤ d(Ri) and yi ≤ d(Ri). For affirmation (a), assume that for some i, xiPiyi, for some j, xjPjyj, and for all k ∈ N \{i, j}, ykPkxk. Now, since we have by (b), xiPixi, we consider an allocation z ∈ X such that zi = xj, zj = rj(xj), and zk = yk. Thus we have ziPixi, zj ∼j xj, and zkPkxk, and so x ∉ P (R), a contradiction. Q.E.D.

Through Proposition 3 and Lemma 3, we complete the proof of the following proposition.

Proposition 6 The intersection of the Pareto correspondence with the no-envy correspondence satisfies Maskin monotonicity.

Now, we examine the intersection of the Pareto correspondence with the individually rational correspondence from equal division. We provide the following lemma.

Lemma 4 On a single-dipped domain, the intersection of the Pareto correspondence with the individually rational correspondence from equal division is not empty.

Proof. By the same reasoning in the proof of Lemma 3, we show that for all

R ∈ ℜ

sd, (

P ∩

Ied)(

R) = ∅; i.e., there exists

x ∈

X such that

x ∈

P (

R) and

x ∈

Ied(

R). Suppose not; there exists

R ∈ ℜ

sd, for all

x ∈

X,

x ∈

P (

R) but

x ∉

Ied(

R). This means that (

a) ∄

y ∈

X such that for all

i ∈

N,

yiRixi, and for some

i ∈

N,

yiPixi, but (

b) there exists an agent

i such that

![Games 04 00038 i002]() Pixi

Pixi. Assume that for all

i ∈

N,

xi ≤

d(

Ri) and

yi ≤

d(

Ri), and for some

i,

j, and for all

k ∈

N \{

i,

j},

yk <

xj <

xi <

![Games 04 00038 i002]()

<

yi <

yj ≤

d(

Rj) <

xk ≤

di(

Ri) ≤

d(

Rk) (

c). Thus, for affirmation (

a), we have for some

i,

xiPiyi, for some

j,

xjPjyj, and for all

k ∈

N \{

i,

j},

ykPkxk. Now, since we have by (

b),

![Games 04 00038 i002]() Pixi

Pixi, we consider an allocation

z ∈

X such that

zi =

![Games 04 00038 i002]()

,

zj =

xj, and

zk =

yj. Thus we have

ziPixi,

zj ∼

j xj, and by (

c),

zk =

yj <

xk ≤

d(

Rk), and so

zkPkxk, and therefore

x ∉

P (

R), a contradiction. Q.E.D.

Through Proposition 4 and Lemma 4, we complete the proof of the following proposition.

Proposition 7 The intersection of the Pareto correspondence with the individually rational correspondence from equal division satisfies Maskin monotonicity.

3.2.2. No-Veto Power

We check whether the monotonic correspondences satisfy this additional condition for sufficiency or not. We provide the following proposition.

Proposition 8 The no-envy solution, the individually rational correspondence from equal division, (NE∩Ied) correspondence, as well as the intersections of these solutions with the Pareto correspondence all fail to satisfy no-veto power.

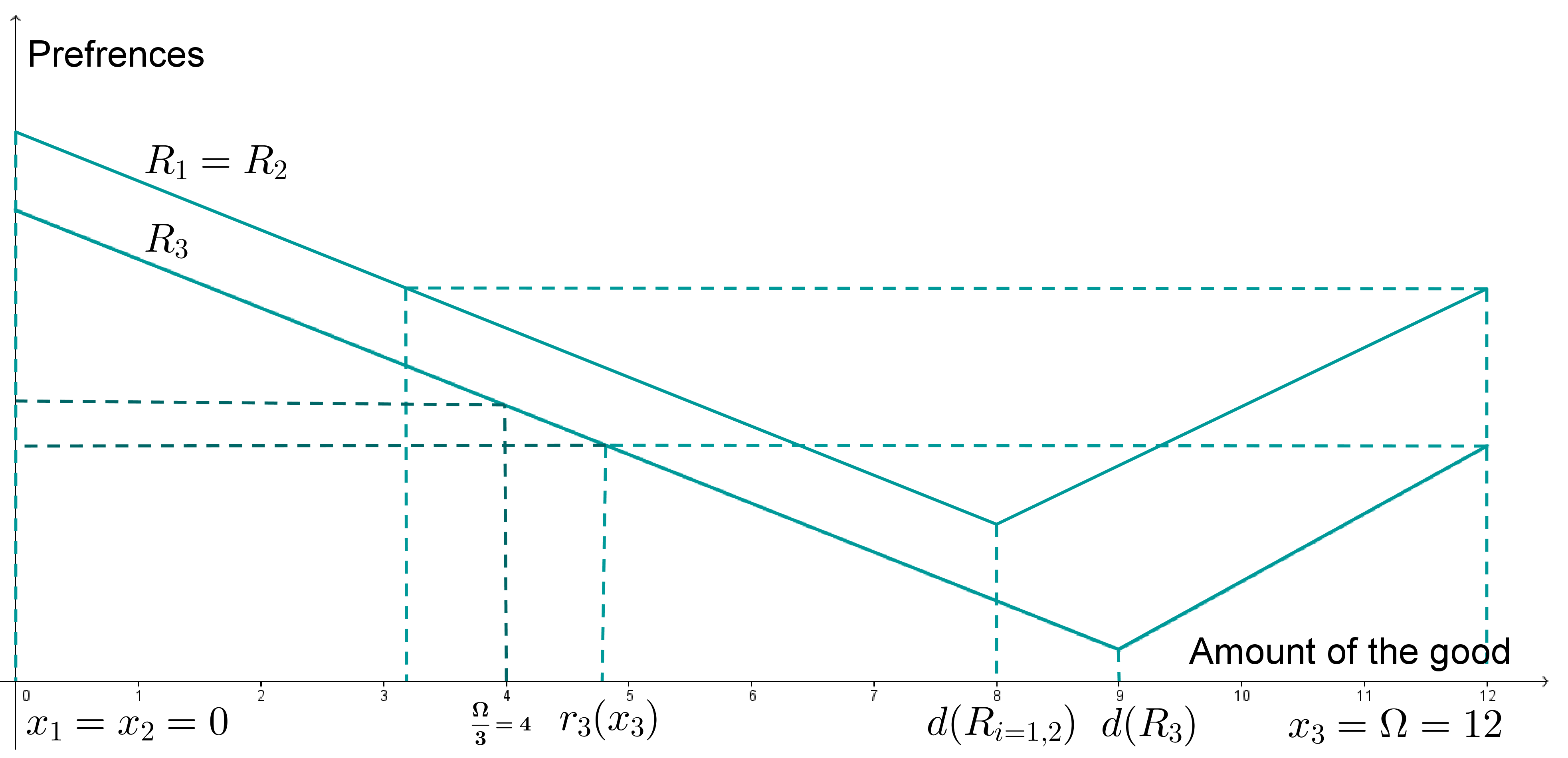

Proof. Let

R ∈ ℜ

sd, Ω = 12,

x = (0, 0, 12) ∈

X. Let

R1 =

R2, for these profile,

L(

xi = 1,2,

Ri = 1,2 = [0, Ω].

Figure 2 illustrates such representations. Also, we have

xi = 1,2P3x3, hence

x ∉

NE(

R).

For the individually rational correspondence from equal division, we have from

Figure 2,

L(

xi = 1,2,

Ri = 1,2 = [0, Ω], but

![Games 04 00038 i003]() P3x3

P3x3. Hence

x ∉

Ied(

R). Thus

x ∉ (

NE ∩

Ied)(

R). From Proposition 6 in Doghmi and Ziad [

5], the Pareto correspondence violates no-veto power and hence the intersections of these solutions with the Pareto correspondence all fail to satisfy no-veto power. Q.E.D.

We conclude that, in the domain of the allocation problem with single-dipped preferences, Maskin’s theorem is silent about the implementability of the monotonic correspondences under consideration. By Theorem 1, all these monotonic correspondences are Nash implementable.

∈ ℜ, for any i ∈ N, [0, Ω] = L(xi,

∈ ℜ, for any i ∈ N, [0, Ω] = L(xi,  ), and x ∉ F (

), and x ∉ F (  ). We have for all i ∈ N, LS(xi, Ri) ∪{xi}⊆ [0, Ω] = L(xi,

). We have for all i ∈ N, LS(xi, Ri) ∪{xi}⊆ [0, Ω] = L(xi,  ). By strict monotonicity, x ∈ F (

). By strict monotonicity, x ∈ F (  ),a contradiction. Q.E.D.

),a contradiction. Q.E.D.  Pixi. Assume that for all i ∈ N, xi ≤ d(Ri) and yi ≤ d(Ri), and for some i, j, and for all k ∈ N \{i, j}, yk < xj < xi <

Pixi. Assume that for all i ∈ N, xi ≤ d(Ri) and yi ≤ d(Ri), and for some i, j, and for all k ∈ N \{i, j}, yk < xj < xi <  < yi < yj ≤ d(Rj) < xk ≤ di(Ri) ≤ d(Rk) (c). Thus, for affirmation (a), we have for some i, xiPiyi, for some j, xjPjyj, and for all k ∈ N \{i, j}, ykPkxk. Now, since we have by (b),

< yi < yj ≤ d(Rj) < xk ≤ di(Ri) ≤ d(Rk) (c). Thus, for affirmation (a), we have for some i, xiPiyi, for some j, xjPjyj, and for all k ∈ N \{i, j}, ykPkxk. Now, since we have by (b),  Pixi, we consider an allocation z ∈ X such that zi =

Pixi, we consider an allocation z ∈ X such that zi =  , zj = xj, and zk = yj. Thus we have ziPixi, zj ∼j xj, and by (c), zk = yj < xk ≤ d(Rk), and so zkPkxk, and therefore x ∉ P (R), a contradiction. Q.E.D.

, zj = xj, and zk = yj. Thus we have ziPixi, zj ∼j xj, and by (c), zk = yj < xk ≤ d(Rk), and so zkPkxk, and therefore x ∉ P (R), a contradiction. Q.E.D.  P3x3. Hence x ∉ Ied(R). Thus x ∉ (NE ∩ Ied)(R). From Proposition 6 in Doghmi and Ziad [5], the Pareto correspondence violates no-veto power and hence the intersections of these solutions with the Pareto correspondence all fail to satisfy no-veto power. Q.E.D.

P3x3. Hence x ∉ Ied(R). Thus x ∉ (NE ∩ Ied)(R). From Proposition 6 in Doghmi and Ziad [5], the Pareto correspondence violates no-veto power and hence the intersections of these solutions with the Pareto correspondence all fail to satisfy no-veto power. Q.E.D.