The “Value Principle” in Management Practices, Organizational Design, and Industrial Organization †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model

2.1. Technology, Preferences, Demographics

2.2. Timing and Contractibility

2.3. Functional Forms

2.4. Demand

2.5. On Interpreting (Market) “Value”

3. Ownership Structures in Industry Equilibrium

3.1. A Competitive Industry with Competitive Managerial Market

3.2. Endogenous Market Structure and Imperfect Competition

- (i)

- There exists a valuation level for which implies that the industry is perfectly competitive, and no enterprises have professional managers.

- (ii)

- There exists such that implies that the industry is monopolized, with a professional manager ensuring compliance with output restrictions.

- (iii)

- For , industry concentration is decreasing in A; professional management is used by all enterprises.

4. Other Management Practices: Centralization, Decentralization, and Favoritism

4.1. Delegation

- Centralization when ;

- Favoritism when ;

- Decentralization when .

- Centralization when ;

- Decentralization when .

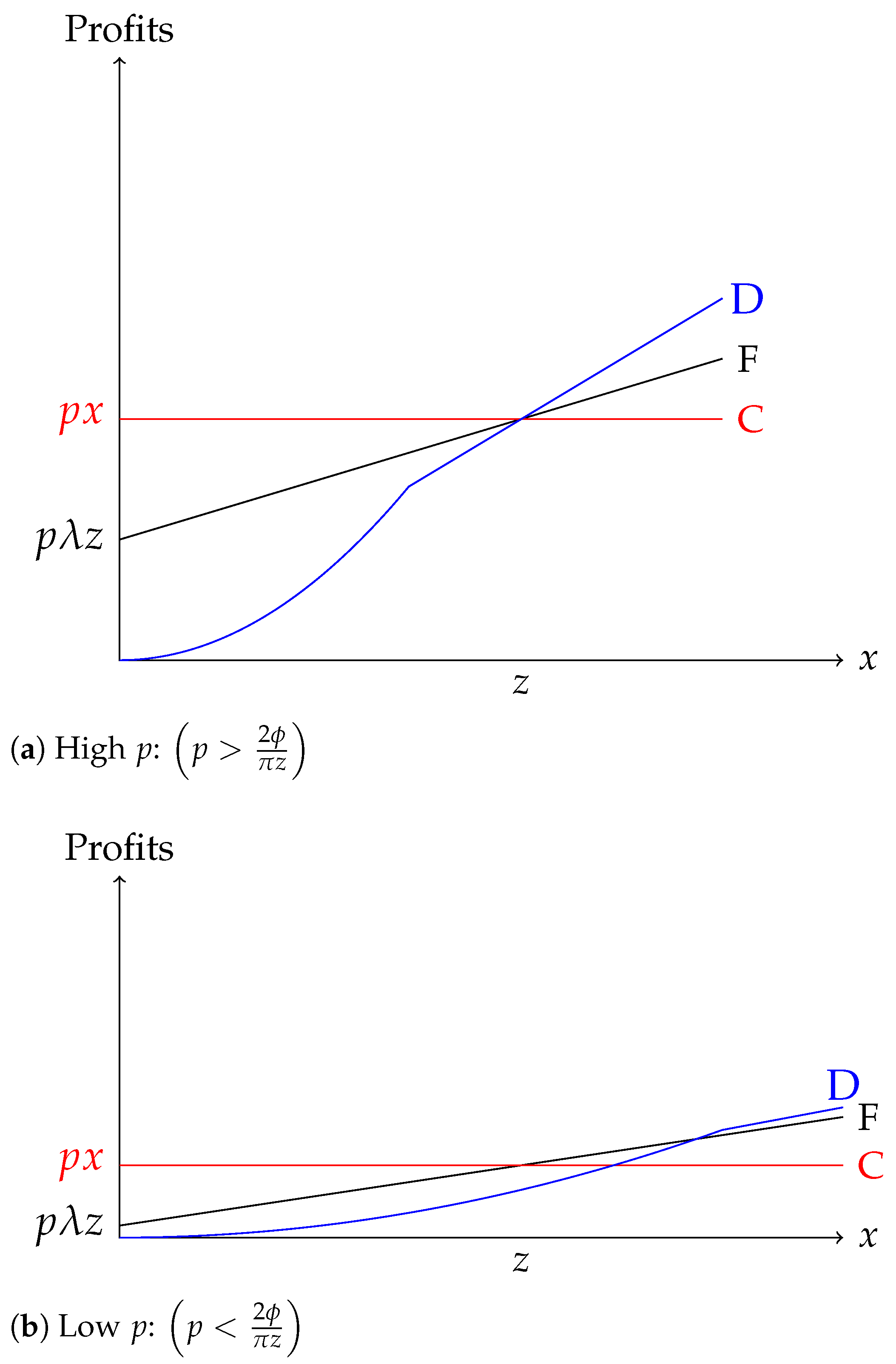

- (i)

- Centralization is independent of industry price p;

- (ii)

- Favoritism is non-increasing in p;

- (iii)

- Decentralization is non-decreasing in p.

4.2. Efficient Control

4.3. Productivity of Different Internal Control Structures

4.4. Delegation and the Diffusion of Productivity Shocks

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Notwithstanding the symmetry of the two decision makers in an enterprise, the setup allows for interpretation of the inputs not merely as investments like “effort”, but also, as in Hart and Holmström (2010) and Legros and Newman (2013), as degrees of concession on standards or working environment over which the two parties disagree, but where successful production only requires adoption of standards that are close. As an illustration, define and , where is a metric with . E’s cost is , while S’s is : expected output depends only on the distance between and . E favors standard 0, while S favors standard 1. In other words, the “effort” cost is increasing in the amount of concession to the partner’s preferred choice. |

| 2 | What about a owning just one of E and S instead of both, or E owning S (or vice versa)? As will become clear in Section 4 on internal control structures, given the behavior of the players, these ownership structures turn out to be dominated by ownership of the entire enterprise because of the high private costs they impose on subordinate parties. |

| 3 | In Legros et al. (2025) each (there called HQ) can own only a single enterprise, but professional managers are abundant (i.e., their measure exceeds the scarcer of the two other types of players). |

| 4 | In the perfectly competitive setting that we consider in Section 3.1, as in most of organizational economics, some form of internal diseconomy of scale/scope/span, here represented by , must be invoked to prevent a firm from growing indefinitely in size (that is, the number of enterprises under a single party’s ownership); absent such costs, if it pays to integrate one enterprise, it will typically pay to integrate all of them, leading to one giant firm, inconsistent with competitive behavior, not to mention empirical reality. In Section 3.2, where we deal explicitly with the endogenous determination of oligopolistic market structure, following Legros et al. (2025), we set . |

| 5 | See Legros and Newman (2008) for an in-depth analysis of the case where actors are liquidity constrained and ownership structure is, therefore, determined by distributional factors, e.g., relative scarcity of E’s and S’s in the supplier market. |

| 6 | In terms of the earlier discussion in Note 1 of the coordination-on-standards interpretation, this corresponds to the metric . |

| 7 | Each partner has share 1/2 of the realized revenue and therefore solves (recall ), resulting in . |

| 8 | Suppose that at least part of the ’s management cost is from non-contractible inputs such as effort; a zero profit share would not incentivize the to bother running the firm, which would perform poorly. See Legros and Newman (2013) for more discussion of reasons why at least part of the ’s compensation would include a share of profit/revenue. |

| 9 | When condition (1) fails, the non-monotonicity in ownership structure leads to a non-monotonic supply curve; more on this below. |

| 10 | See Dam and Serfes (2021) for detailed discussion of this possibility for a setting similar to the present one. De Meza and Southey (1999) discusses non-monotone supply for an environment similar to the one in Legros and Newman (1996), where the organizational trade-off is between profit sharing and monitoring. |

| 11 | Technically, the firms in the previous subsection might also be considered “horizontally integrated” as each potentially owns more than one substitutable enterprise. We reserve the term for situations in which integration changes the degree of market power that the owner can exert. |

| 12 | Unlike here, Legros et al. (2025) does not consider profit sharing for unmanaged (non-integrated) producers and does not study the effects of consumer willingness to pay on market structure and vertical integration. |

| 13 | Though we abstract from the possibility here, in case an endogenous competitive fringe emerges in equilibrium, some s buy only a zero measure of enterprises and subsequently behave as price-takers, setting their subordinate enterprise’s output equal to the unit capacity, as in the previous subsection. |

| 14 | In contrast to the standard endogenous entry model of IO, wherein the most common interpretation of fractional equilibrium values of n is , here such values mean either that the unique equilbrium is a situation in which large enterprises coexist with an (endogenous) competitive fringe, or it is one with large firms and no fringe. We ignore the possibility of a positive-measure fringe here for simplicity. See Legros et al. (2025) for further discussion, in particular how the continuous model approximates the one in which n is confined to the positive integers. |

| 15 | For example, a unit-measure continuum of consumers with valuations for an indivisible good uniformly distributed in . |

| 16 | Legros et al. (2025) shows that this is, in fact, an outcome of the competition among s in the market for assets, given the identical enterprises, their strictly convex effort costs, and the tie-breaking rule s follow to minimize aggregate costs of the enterprises they own. |

| 17 | Legros et al. (2025) shows that this is a stable outcome of competition among s for enterprises: any other configuration would be vulnerable to a (possibly coordinated) sequence of offers that raise the payoffs of every enterprise. In a stable configuration, all enterprises receive the same payoffs, s make zero profits in the asset market (i.e., profits made in the product market are offset by asset acquisition prices), and, as already mentioned, large firms are symmetric. |

| 18 | See Alfaro et al. (2024); Baker et al. (1999) for more discussion on the differences between delegation and contractible control. |

| 19 | The model studied in this section is inspired by Alfaro et al. (2024), but there are several differences. Most saliently, in that paper, subordinates are completely independent, so there is no room for the favoritism externalities emphasized here. |

| 20 | The justification for no renegotiation is the same as that for using delegation in the first place: neither x nor the identity of who actually made a non-verifiable decision is itself verifiable; see Alfaro et al. (2024). |

| 21 | While this is the unique subgame perfect equilibrium outcome with the moving after observing , it is also a Nash equilibrium outcome of a simultaneous move version of the game between the and E. However there are many other Nash equilibria, all delivering maximal expected output, but differing in the private costs incurred by E and S; ours is the limit of models in which the production function is replaced with approximating ones in which marginal returns to the non-contractible inputs above are positive instead of zero, but vanish in the limit (e.g., with ; then the follows her dominant strategy, setting for every , while as vanishes). |

| 22 | As we have modeled it, the choice of favoring E or S is arbitrary; if each party had different competencies, then the would assign control to the more able, even if the difference is small. Likely, the choice of E versus S could reflect productivity-irrelevant influence activities. Either way, there is a large shift in private costs for a potentially small productivity gain. |

| 23 | The restriction of ownership structures to non-integration and joint ownership by the alluded to in Note 2 is justified by the same logic: single-asset ownership by the and E- (or S-) ownership generate the same low payoffs as favoritism does here. |

| 24 | Looking across a set of firms, those that are centralized would have average productivity z, those that are partially decentralized would have productivity , and decentralized ones would have productivity ). |

| 25 | It is easily checked that efficient decentralization need not be more productive than centralization; in the neighborhood of the cutoff the large private cost savings from the former may more than compensate for the lost output and profit. |

| 26 | Industry supply is . |

| 27 | One possible cost of entry is an opportunity cost in terms of foregone entrepreneurship. One more manager may mean one enterprise lost, but some of the remaining enterprises will be better operated. Investigating this trade-off is left for future work. |

References

- Alfaro, L., Bloom, N., Conconi, P., Fadinger, H., Legros, P., Newman, A. F., Sadun, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2024). Come together: Firm boundaries and delegation. Journal of the European Economic Association, 22(1), 34–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, L., Conconi, P., Fadinger, H., & Newman, A. F. (2016). Do prices determine vertical integration? Review of Economic Studies, 83(3), 855–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G., Gibbons, R., & Murphy, K. J. (1999). Informal authority in organizations. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 15(1), 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A. V., & Newman, A. F. (1993). Occupational choice and the process of development. Journal of Political Economy, 101(2), 274–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, P., Mookherjee, D., & Tsumagari, M. (2021). Middlemen margins and globalization. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 5(4), 81–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T., Fontana, N., & Limodio, N. (2021). Antitrust policies and profitability in nontradable sectors. American Economic Review: Insights, 3(2), 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N., Eifert, B., Mahajan, A., McKenzie, D., & Roberts, J. (2013). Does management matter? Evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1), 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N., Mahajan, A., McKenzie, D., & Roberts, J. (2020). Do management interventions last? Evidence from India. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12(2), 198–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N., & Van Reenen, J. (2006). Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(4), 1351–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnahan, T. F., Brynjolfsson, E., & Hitt, L. M. (2002). Information technology, workplace organization, and the demand for skilled labor: Firm-level evidence. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 339–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E. (1993). The productivity paradox of information technology. Communications of the ACM, 36(12), 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, F. F. D. (1972). The godfather. Paramount Pictures. [Google Scholar]

- Dam, K., & Serfes, K. (2021). A price theory of vertical and lateral integration under productivity heterogeneity. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 69(4), 751–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meza, D., & Southey, C. (1999). Too much monitoring, not enough performance pay. Economic Journal, 109(454), 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S., & Lederman, M. (2009). Adaptation and vertical integration in the airline industry. American Economic Review, 99(5), 1831–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S., & Lederman, M. (2010). Does vertical integration affect firm performance? Evidence from the airline industry. RAND Journal of Economics, 41(4), 765–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garicano, L. (2000). Hierarchies and the organization of knowledge in production. Journal of Political Economy, 108(5), 874–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R., & Henderson, R. (2013). What do managers do?: Exploring persistent performance differences among seemingly similar enterprises. In J. Roberts, & R. Gibbons (Eds.), Handbook of organizational economics. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G., & Helpman, E. (2002). Integration versus outsourcing in industry equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 85–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, S., & Hart, O. (1986). The costs and benefits of ownership: A theory of vertical and lateral integration. Journal of Political Economy, 94(4), 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, O., & Holmström, B. (2010). A theory of firm scope. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(2), 483–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, O., & Moore, J. (1990). Property rights and the nature of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 98(6), 1119–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-T., & Olken, B. A. (2014). The missing “missing middle”. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legros, P., & Newman, A. F. (1996). Wealth effects, distribution, and the theory of organization. Journal of Economic Theory, 70(2), 312–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legros, P., & Newman, A. F. (2008). Competing for ownership. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(6), 1279–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legros, P., & Newman, A. F. (2013). A price theory of vertical and lateral integration. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2), 725–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legros, P., & Newman, A. F. (2017). Demand-driven integration and divorcement policy. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 53, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legros, P., Newman, A. F., & Udvari, Z. (2025). Competing for the quiet life: An organizational theory of market structure. Mimeo. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan, D. (2017). Digging deep to compete: Vertical integration, product market competition, and prices. Journal of Industrial Economics, 65(4), 683–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, D., & Woodruff, C. (2017). Business practices in small firms in developing countries. Management Science, 63(9), 2773–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R. M. (1987, July 12). We’d better watch out: Review of S.S. Cohen and J. Zysman, Manufacturing matters: The myth of the post-industrial economy. New York Times Book Review. [Google Scholar]

- Stigler, G. J. (1950). Monopoly and oligopoly by merger. The American Economic Review, 40(2), 23–34. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Legros, P.; Newman, A.F. The “Value Principle” in Management Practices, Organizational Design, and Industrial Organization. Games 2025, 16, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16050050

Legros P, Newman AF. The “Value Principle” in Management Practices, Organizational Design, and Industrial Organization. Games. 2025; 16(5):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16050050

Chicago/Turabian StyleLegros, Patrick, and Andrew F. Newman. 2025. "The “Value Principle” in Management Practices, Organizational Design, and Industrial Organization" Games 16, no. 5: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16050050

APA StyleLegros, P., & Newman, A. F. (2025). The “Value Principle” in Management Practices, Organizational Design, and Industrial Organization. Games, 16(5), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16050050