Abstract

The asymptotical properties of a special dynamic two-person game are examined under best-response dynamics in both discrete and continuos time scales. The direction of strategy changes by the players depend on the best responses to the strategies of the competitors and on their own strategies. Conditions are given first for the local asymptotical stability of the equilibrium if instantaneous data are available to the players concerning all current strategies. Next, it is assumed that only delayed information is available about one or more strategies. In the discrete case, the presence of delays has an effect on only the order of the governing difference equations. Under continuous scales, several possibilities are considered: each player has a delay in the strategy of its competitor; player 1 has identical delays in both strategies; the players have identical delays in their own strategies; player 1 has different delays in both strategies; and the players have different delays in their own strategies. In all cases, it is assumed that the equilibrium is asymptotically stable without delays, and we examine how delays can make the equilibrium unstable. For small delays, the stability is preserved. In the cases of one-delay models, the critical value of the delay is determined when stability changes to instability. In the cases of two and three delays, the stability-switching curves are determined in the two-dimensional space of the delays, where stability becomes lost if the delay pair crosses this curve. The methodology is different for the one-, two-, and three-delay cases outlined in this paper.

1. Introduction

Game theory is one of the most frequently studied fields in mathematical economics. Its foundation and main concepts are discussed in many textbooks and monographs, for example, Dresher (1961), Szép and Forgó (1985), Vorob’ev (1994), and Matsumoto and Szidarovszky (2016) [1,2,3,4]. These include both two-person and general n-person games. In the earliest decades, the existence and uniqueness of the Nash equilibrium were the central research issues (von Neumann and Morgenstern, 1944; Nash, 1951; Fudenberg and Tirole, 1991; Rosen, 1965) [5,6,7,8], and then the dynamic extensions of these static games received increasing attention (Okuguchi, 1976; Hahn, 1962) [9,10]. Models have been developed and examined in both discrete and continuous time scales. In most studies, the dynamic processes are driven by either gradient adjustments or best-response dynamics. In the first case, only interior equilibria are the steady states of the resulting dynamic systems. In the second case, this difficulty is avoided; however, the construction of the dynamic processes requires knowledge of the best responses of the players (Bischi et al., 2010) [11]. In both cases, the asymptotical stability of the equilibrium in examined by applying the Lyapunov theory (Cheban, 2013, Saeed, 2017) [12,13] or local linearization (Bischi et al., 2010) [11]. In the discrete case, the theory of noninvertable maps and critical sets is a commonly used approach for nonlinear discrete systems (Gumowski and Mira, 1980; Mira et al., 1996) [14,15], while for continuous systems Bellman (1969), LaSalle (1968), and Sánchez (1968) [16,17,18] can be suggested as the main references. After developments in the stability theory of differential equations, time delays were added to dynamic models, in which it is usually assumed that the players make decisions based on delayed information about their own and others’ actions. This additional assumption makes the models more realistic, since data collection, determining the best decision alternatives, and their implementation need time (Bellman and Cooke, 1963) [19]. Delay systems have many applications in population dynamics (Kuang, 1993; Cushing, 1977) [20,21]; economics (Gori et al., 2014; Ösbay et al., 2017) [22,23]; and engineering (Berezowski, 2001; Wang et al., 1999) [24,25], among other disciplines.

A two-person continuous game is considered, in which the strategy sets and are compact intervals and the payoff functions () are continuous and strictly concave in , which is the strategy of player k. Under these conditions, has a unique maximizer for all . This function is called the best response of player k. At each time period, the players select strategies to move closer to their best responses. In the discrete case, this concept is realized by the difference equation system

where and are positive adjustment coefficients. In order to avoid overshooting, it is assumed that both are less than unity. In the continuous case, the following differential equation system describes the dynamic evolution of the strategies:

where .

We provide one example here. Consider a duopoly, when two firms produce the same product and sell their outputs in the same market. Let and denote the production levels of the firms. The production costs are

and the selling unit price is

The profit of firm i () is given as the difference between its revenue and cost:

It is a natural assumption that firm i does not have instantaneous information on the output level of the competitor, so at time t, it believes that the output of the competitor is . The marginal profit of the firm is clearly

Hence, at time t, the best believed response of firm i is

The best response dynamics have the following forms:

in the discrete-time case, and

in the continuous-time case, leading to a delay difference and differential equations.

In this paper, a special two-person game is examined with best-response dynamics in discrete and continuous time scales. The main question we try to answer is the following: How does the presence of time delays affect the asymptotical properties of a dynamics extension of a special stable two-person game? In the case of one delay, the stability interval or intervals are determined when the stability of the equilibrium is still preserved. In the case of multiple delays, the stability regions in the delay space are determined, where the equilibrium is still stable. This paper introduces a mathematical methodology to find the stability intervals and regions.

The paper is developed as follows. Section 2 considers discrete time scales and is divided into two parts: models with and without time delays. The structure of Section 3 is similar, with two subsections. Section 4 introduces and examines alternative models, and Section 5 offers concluding remarks and further research areas.

2. Discrete Systems

2.1. Stability without Time Delays

Assuming the differentiability of the best-response functions, we can linearize Equations (1) and (2) about an equilibrium that is also a steady state of the system. Let and denote the equilibrium strategies and let

be the discrepancies of the strategies from their equilibrium levels. Linearizing Equations (1) and (2) around gives the following:

and

This is a linear system. The asymptotic behavior of the state trajectories depends on the locations of the eigenvalues of the system. For finding the eigenvalues, we consider exponential solutions and . Substituting them into Equations and , we see that

After simplifying both equations by , a linear algebraic system is obtained for u and v, and nonzero solutions exist if and only if the determinant of the system is zero:

This is a quadratic polynomial with

It is well known (see, for example, Appendix F of Bischi et al., 2010) [11] that its roots are inside the unit circle if and only if

In our case, these conditions can be written as

Since and are below unity, the first inequality is stronger than the second one, so we have the following:

Proposition 1.

The equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable if and only if

Notice that

so the left-hand side of condition (8) is negative and below

2.2. Stability with Delays

It is now assumed that the players have access only to delayed information about the strategies of the others. We can select the time unit as the length of the common delay. Thus, in Equation (1), is replaced by , and in (2), is replaced by . Assuming again exponential solutions and , we have

After simplifying by , the resulting algebraic system has the form

A nonzero solution of u and v exists if and only if

This is a quartic equation with

Farebrother (1973) [26] showed that the sufficient and necessary conditions to only have roots inside the unit circle are as follows:

Notice that the first four inequalities are linear in as well as in ; however, the last inequality is cubic in , so it is difficult to find simple stability conditions. Nevertheless, the first four inequalities give necessary stability conditions. They can be written as

Notice that

and

Hence, the necessary conditions are

In this case,

Let denote the left-hand side of last stability condition. Notice that

so its sign is indeterminate in general.

We will now examine the addition condition in interval . Clearly,

Notice first that

and

Since

the stationary points of are

where

implying that and Clearly,

being outside the range of the necessary condition. Additionally,

and

Notice that

and so has three real roots: one before one between 0 and and one after 1. Consequently, if denotes the negative root and the positive root between 0 and 1, then if

or

Proposition 2.

A necessary condition for the local asymptotical stability of the equilibrium in the delayed model is condition (9). A sufficient and necessary condition is the simultaneous satisfaction of (9) and (10).

3. Continuous Systems

3.1. Stability without Time Delays

We will now examine the stability of systems (3) and (4). Similarly to the discrete case, we linearize the system around the equilibrium to have the following:

where overbar is avoided for simple notation. In order to find the eigenvalues, we look for the solutions in exponential forms as before:

The substitution of these solutions into Equations (11) and (12) gives

After simplifying both equations by , the resulting algebraic system for u and v has nonzero solutions if and only if

This is a quadratic polynomial, , with

It is well known (Bischi et al., 2010) [11] that the real parts of the roots of this quadratic equation are negative if and only if both and are positive, which implies the following:

Proposition 3.

The equilibrium with dynamics (3) and (4) is locally asymptotically stable if

and unstable if .

In comparing conditions (8), (9), (10), and (13), it is clear that the stability of the equilibrium with the continuous model is implied by its stability for the discrete cases with and without delays. In comparing the two discrete cases, notice that the sufficient and necessary stability condition of the no-delay case implies the necessary conditions for the delay case since

or

3.2. Stability with Delays

Assume again that both players face delays, and in the information about the strategies of the others. Therefore, in Equation (3), is replaced by , and in (4), is replaced by . The linearized equations can therefore be written as follows:

The eigenvalues clearly depend on the lengths of the delays. Searching for exponential solutions

and substituting them into these equations, we obtain

After simplifying by , the resulting algebraic equations for u and v have nonzero solutions if and only if

Notice first that the characteristic equation does not depend on the individual values of and —it depends on only . We know that at (no-delay case), the equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable if (13) holds. By increasing the value of from zero, the stability might be lost. In this case, an eigenvalue has a zero real part, . Since the complex conjugate of an eigenvalue is also an eigenvalue, we can assume that . Substituting this eigenvalue into the characteristic Equation (16), we have the following:

The separation of the real and imaginary parts shows that

By adding the squares of these equations, we have

If , then no stability switch occurs. If , then the equilibrium remains locally asymptotically stable for all . If , then the characteristic equation of the no-delay case has a negative and a zero eigenvalue. Thus, no conclusion can be drawn about stability, and the same is the case for all .

Assume next that In this case, Equation (19) has two real roots for

where

implying that and . Thus, we have a unique solution . From (17) and (18), we see that and

Therefore, we have the critical values of the delay:

The direction of the stability switches can be determined by Hopf bifurcation. For this purpose, we select as the bifurcation parameter and consider the eigenvalues as functions of : . Implicitly differentiating the characteristic Equation (16) with respect to , we have

implying that

Notice that the real parts of and have the same sign and at , the last term is a pure imaginary number with a zero real part. At , the first term equals

The real part of this expression has the same sign as

implying that at any critical value, at least one eigenvalue changes the sign of its real part from negative to positive. Consequently, stability cannot be regained with delayed information.

Assume next that . The equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable without delays. From Equations (17) and (18), we see that and

Hence, the critical values are

and at the smallest critical value stability is lost.

In summary, we have the following results:

Proposition 4.

(a) If , then the equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable for . At , the stability is lost via Hopf bifurcation. (b) If , then the equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable for all . (c) If , then the equilibrium is unstable for all . (d) If , then no stability result can be determined for .

4. Alternative Models

4.1. One-Delay Models

Consider first the case where the first player faces delays in its own and the other player’s strategy. In this case, Equations (3) and (4) are modified as follows:

Linearization around the equilibrium gives

Assuming again exponential solutions,

and substituting them into the linearized equations, we have

After simplifying with , the resulting algebraic equations have nonzero solutions if and only if

We showed earlier that the equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable if and unstable if . By increasing the value of from zero, stability might be lost or regained when . Substituting this eigenvalue into Equation (26), we have

The separation of the real and imaginary parts shows that

Adding up the squares of these equations, we have

There is a positive solution for

with

For the sake of notational convenience, let

in order to give

implying that

Thus,

or

and

If then sin and

and the critical values are

If then nothing can be concluded about stability in the no-delay case. From (27), the nonzero solution is

Thus, if then no stability switch occurs, and if then

If , then the equilibrium is unstable without delays. In this case, and

The critical values are as follows:

The directions of the stability switches are determined by Hopf bifurcation. Assuming that , we differentiate implicitly Equation (26) with respect to to obtain

implying that

From we know that

implying that

from which we have

At , this expression becomes

We first simplify the numerator,

The denominator is the following:

After multiplying both N and D by the complex conjugate of D, the denominator becomes positive, and the real part of the numerator becomes

It can be shown that (34) can be simplified as

which is positve if . Thus, if the equilibrium is stable with in the no-delay case, then stability is lost at , and stability cannot be regained with larger values of delay.

Another model is obtained if we assume that both players have delays in their own strategies. Then, Equations (3) and (4) become

The linearized equations are

Substituting exponential solutions as before, we have

After simplifying with , the resulting algebraic system for u and v has nonzero solutions if and only if

Multiplying these equations by , we obtain

Assuming again that the eigenvalue has a zero real part, , we substitute it into this equation to obtain

Separating the real and imaginary parts, we have

Now, we have two cases:

- (a)

- .

If , no stability switch occurs. If , then the unique solution is

and if and , then we have again one positive solution, . Otherwise, both and are solutions. In the case of one solution, the critical values are

and in the case of two solutions,

and

If , then no stability switch occurs. If , then , implying that there is no stability switch. Otherwise, there is a unique positive root,

Then, the critical values are

- (b)

The multiplier of in (43) can be rewritten as

From (43),

If , then the equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable without delay, and we have a positive value,

Furthermore, the critical values are

and

In the special case, when Equation (43) shows that is the only solution implying that no stability switch occurs.

4.2. Two-Delay Model

Assume next that player 1 faces different delays in the data of its own strategy and that of the other player. The associated dynamic equations have the forms

and the corresponding linearized system is as follows:

Substituting exponential solutions again into these equations, after simplifying by , we have

with determinant equation

where

In order to guarantee that Equation (46) is the characteristic equation of a delay system, we assume the following:

- (a)

- so there are finitely many eigenvalues on . This clearly holds.

- (b)

- which holds if , as is assumed in the following.

- (c)

- Polynomials and have no common roots. This is obvious if . If then is a common root, which does not remove stability.

- (d)

- which is again obvious, since is quadratic, is linear, and is constant.

We will now follow the suggestions given by Gu et al. (2005) [27]. Dividing both sides of (46) by , we obtain

where

and

However, if as well, then implies no solution, and implies that arbitrary positive and values are solutions. Notice that this case cannot occur, since has only two real roots, and .

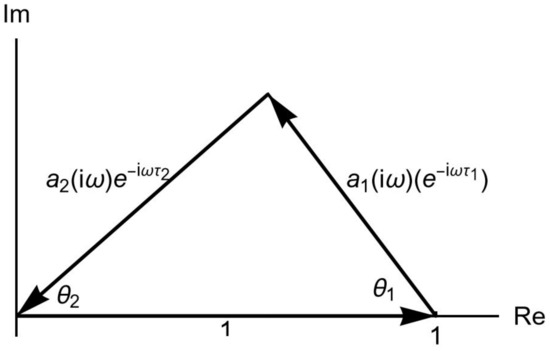

Consider next the case of . Then, notice that the complex vectors , and form a triangle in the complex plane, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Triangle constructed by these vectors.

If , then, similarly,

implying that is arbitrary and

If and are nonzero, then the three vectors form a triangle if and only if

In our case,

Relations (48) and (49) are quartic inequalities. In general, they cannot be solved, but if the numerical values are known, then the roots of the quartic equations can be determined, and certain segments between the roots provide solutions. The law of cosine can be used to find angles and :

and

The triangle can be placed above and under the horizontal axis, so from Figure 1, we have

and

implying that the critical values are as follows:

and

Let denote the set of all solutions of conditions (48) and (49), which consists finitely of many intervals:

For we define

and

The set T of all stability-switching curves is the union of all sets . By not restricting and to interval , we make them continuous functions of in , so with fixed n and m, and also become continuous curves.

Notice that any left endpoint and right endpoint of satisfy at least one of the conditions (48) and (49) by equality, so one of the following equalities must hold:

and the case of and are also possible. If (52) holds, then and is connected with at this endpoint. If (53) holds, then similarly, and , so is connected with at this endpoint, and if (54) is satisfied, then and , showing that at this endpoint is connected with . If , then as , both and converge to infinity. This discussion shows that the stability-switching curve T is the intersection of and conforms to one of the following types:

- (i)

- A series of closed curves;

- (ii)

- A series of spiral-like curves with either horizontal, vertical, or diagonal axes;

- (iii)

- A series of open-ended curves with endpoints converging to infinity.

If a point () crosses the stability-switching curve, then stability switching might occur. Before discussing the direction of stability switching (stability loss or gain), some comments are in order.

The direction of a curve is positive if it corresponds to an increasing value of . The direction is reversed if a curve is passing through an endpoint. Moving along a curve in the positive direction, the region on the left-hand side is called the region on the left, and the region on the right right is similar. We define for any point on T the following:

The following result is given by Gu et al. (2005) [27].

Theorem 1.

Let and such that is a simple pure complex eigenvalue. As a point moves from the right to the left of the corresponding curve of , a pair of eigenvalues cross the imaginary axes to the right (stability loss) if . If the inequality is reversed, then the crossing is from right to left (stability gain).

4.3. Three-Delay Model

Consider next the case in which the players have different delays in the data about their own strategies. In this case, the delay equations become

By linearizing these equations around the equilibrium, we obtain

Substituting the exponential solutions

into these equations, we have

After simplifying these equations by , an algebraic equation system is obtained for u and and nonzero solutions exist if and only if

which can be written as

where

The following assumptions are made to guarantee that (57) can be the characteristic equation of a delay system and to exclude some trivial cases:

- (a)

- There are a finite number of eigenvalues on whenThis holds, since is quadratic, while and are linear and is constant.

- (b)

- The zero frequency is not an eigenvalue with any andThis condition holds if , so we have to assume this relation in the following discussion.

- (c)

- Polynomials , and have no common roots, which is trivial in our case.

- (d)

- which also holds, since is quadratic and the others have lower degrees.

In examining the stability switches with Equation (57), we will follow the ideas of Lin and Wang (2012) [28]. We can rewrite Equation (57) at as follows:

Since ,

or

where an overbar indicates a complex conjugate and the arguments of , and are omitted for simple notation. A simple calculation shows that (59) has the equivalent form,

where

With any value of , this is a trigonometric equation for . In our case,

Thus,

and

Similarly,

(A) We assume first that is a solution of equation . Then, , and an arbitrary value of is a solution. The corresponding values of can be obtained from Equation (58) as

If the denominator is zero, then (58) implies that the numerator is also zero, so an arbitrary is a solution.

(B) We assume next that , so . Clearly, there is a such that

The two factors must have different signs, or one of them has to be zero. This inequality and (64) cannot be solved in general, but if numerical values of the model parameters are available, then computer solutions can present finitely many segments as the set of all solutions for , which is denoted by . For each , the corresponding critical values are given by (63), and then from (58), we have

if the denominator is nonzero. If it is zero, then (58) implies that the numerator is also zero, so an arbitrary is the solution.

A more simple method can be suggested by interchanging and and repeating the above procedure for . It can be shown that for each segment the critical values form the curves as follows:

which is continuous in .

With any left and right endpoints and ,

where

therefore,

where . The connection of the segments of the stability-switching curves can be given as follows: connects and at its two ends:

- (i)

- If , then and form a loop, so the set of stability-switching curves is a collection of closed continuous curves.

- (ii)

- Otherwise, it is a collection of continuous curves with endpoints on the axes or extending to infinity in .

The direction of stability switching now depends on

and

and Theorem 1 remains valid with these quantities.

5. Conclusions

In engineering, population dynamics, and realistic economies, there are many examples where only delayed responses can be observed and instantaneous data are not available. In such cases, the design and decisions are based on delayed data and information. In this paper, we presented some important methods to deal with this situation. Under discrete time scales, it is usually assumed that the lengths of the delays are positive integers that only increase the order of the governing difference equations (Matsumoto and Szidarovszky, 2018) [29]. In the continuous case, different methods can be used based on the number of delays. It is always assumed that the equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable without delays, and stability is preserved if the delays are sufficiently small based on the fact that the matrix eigenvalues continuously depend on the matrix elements. However, by increasing the lengths of the delays, this stability might be lost. In the one-delay case, the critical value of the delay was determined when stability turns into instability (Section 3.2 and Section 4.1). In the two-delay case, the two-dimensional space of the delays was considered, and the stability-switching curves were determined (Section 4.2 and Section 4.3). If a pair of delays crosses this curve from the region containing the origin, then stability is lost. The same is the situation in the three-delay case, when two delays and their sum affect the dynamic properties of the equilibrium. The mathematical methodology is different in these cases, which was illustrated in the case of a special two-person game wherein the dynamic evolution of the strategies was governed by best-response dynamics. Several cases were used for the presentation of the methodology, which could be very useful in solving practical problems including one, two, or even three delays. The material of this paper can be extended in several directions. One could include more players, different dynamic rules, and more variants of the delayed quantities. In addition, the Bayesian methodology is used in population dynamics to assess the survival probabilities of competing species (Dragicevic, 2015) [30] or, in general, to find the probability of the occurence of certain properties among the players. For the same issues, artificial neural networks could be an alternative approach (Poulton, 2001; Swingler, 1996) [31,32].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors.; methodology, A.M. and F.S.; software, A.M.; validation, A.M., F.S. and M.H.; formal analysis, F.S.; investigation, M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.; writing—review and editing, M.H.; visualization, A.M.; project administration, F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to three referees; their comments and suggestions were very helpful in finalizing the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dresher, M. Games of Strategy: Theory and Applications; Applied Mathematics Series; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, A.; Szidarovszky, F. Game Theory and Its Applications; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Szep, J.; Forgo, F. Introduction to the Theory of Games; Akademia Kiado: Budapest, Hungary, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Vorob’ev, N.N. Foundation of Game Theory. Noncooperative Games; Birkhäuser: Basel, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fudenberg, D.; Tirole, J. Game Theory; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, H.F., Jr. Noncooperative Games. Ann. Math. 1951, 54, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, J.B. Existence and uniquness of equilibrium points for concave n-person games. Econometrica 1965, 33, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J.; Morgenstern, O. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, F. The stability of the Cournot oligopoly soution. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1962, 29, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuguchi, K. Expectations and Stability in Oligopoly Models; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bischi, G.-I.; Chiarella, C.; Kopel, M.; Szidarovszky, F. Nonlinear Oligopolies: Stability and Bifurcations; Springer, Science+Business Media: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cheban, D.D. Lyapunov Stability of Non-Autonomous Systems; Nova Science Pulisher, Hauppauge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, R. Lyapunov Stability Theorem with Some Applications; LAMBERT, Academic Publishing: Saarbrüchen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gumowski, I.; Mira, C. Dynamique Chaotique; Cepadues Editions: Toulose, France, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Mira, C.; Gardini, L.; Barugola, L.; Cathala, J. Chaotic Dynamics in Two Dimensional Noninvertible Maps; Nonlinear Sciences, Series A; World Scientific: Singapore, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bellman, R. Stability Theory of Differential Equations; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- LaSalle, J.P. Stability theory for ordinary differential equations. J. Differ. Equ. 1968, 4, 37–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.A. Ordinary Differential Equations and Stability Theory; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Bellman, R.; Cooke, K.L. Differential-Difference Equations; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, J. Integro-Differential Equations and Delay Models in Population Dynamics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, Y. Delay Differential Equations with Applications in Population Dynamics; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gori, L.; Guerrini, L.; Mauro, S. Hopf bifurcation in a cobweb model with discrete time delays. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2014, 2014, 137090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ösbay, H.; Saglam, H.; Cagri, H.; Yüksel, M. Hopf bifurcation in one section optimal growth model with time delay. Macroecon. Dyn. 2017, 21, 1887–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezowski, M. Effect of delay time on the generation of chaos in continuous systems: One dimensional model, two dimensional model-tubwar chemical reactor with recycle. Chaos Solitions Fractals 2001, 12, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.G.; Lee, T.H.; Tan, K.K. Time delay systems. In Finite-Spectrum Assignment for Time Delay Systems; Lecture Notes in Control and Information Systems 239; Springer: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Farebrother, R.W. Simplified Samuelson conditions for cubic and quartic equations. Manch. Sch. Econ. Soc. 1973, 41, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, K.; Nicolescu, S.-I.; Chen, J. On stability crossing curves for general systems with two delays. J. Math. Appl. 2005, 311, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wang, H. Stability analysis of delay differential equations with two discrete delays. Can. Appl. Math. 2012, 2, 519–533. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, A.; Szidarovszky, F. Dynamic Oligopolies with Time Delays; Springer-Nature: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dragicevic, A. Bayesian population dynamics of spreading species. Environ. Model. Assess. 2015, 20, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulton, M. Computational Neural Networks for Geophysical Data Processing; Pergaron: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Swingler, K. Applying Neural Networks; Academic: San Diego, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).