Abstract

The primary objective of this paper is to develop a two-country, dynamic, general equilibrium model with innovation contests to formally analyze the impact of globalization on the skill premium and fully-endogenous growth. Higher quality products are endogenously discovered through stochastic and sequential global innovation contests in which challengers devote resources to R&D, while technology leaders undertake rent-protection activities (RPAs) to prolong the expected duration of their temporary monopoly power by hindering the R&D effort of challengers. The model generates intra-sectoral trade, multinationals, and international outsourcing of investment services. Globalization, captured by a move from autarky to the integrated-world equilibrium, leads to convergence of wages and growth rates. Globalization and long-run growth are either substitutes or complements depending on a country’s relative skill abundance and the ranking of skill intensities between RPAs and R&D services. Trade openness between two countries that possess identical relative skill endowments but differ in size does not affect either country’s long-run growth.

Keywords:

innovation contests; economic growth; scale effects; R&D; rent-protection activities; barriers to innovation; skill premium JEL Classification:

F1; F3; F4

1. Introduction

Even though Schumpeterian growth theory is now more than three decades old, our understanding of the nexus among globalization, economic growth and income distribution remains incomplete.1 This paper’s primary objective is to deepen our understanding of the effects of globalization on growth by formally analyzing the role of global innovation contests, skill abundance, activity-specific skill intensities, and the skill premium as key determinants of economic growth.

First-generation models of Schumpeterian growth analyzed the effects of globalization on long-run growth in various contexts. These models highlighted the market-size expansion channel as a key avenue through which globalization accelerates long-run growth. By expanding the size of each participating country’s market, international trade raises the profitability of R&D in all trading partners thereby accelerating the introduction of new products and resulting in faster global long-run growth (Rivera-Batiz and Romer [2,3], Grossman and Helpman [4], Dinopoulos et al. [5], among many others). In short, this literature provided an elegant theoretical justification of the idea that globalization is an engine of economic growth; thus, trade and long-run growth are strong complements.

Unfortunately, the early euphoria on the complementarity between trade and growth did not carry over—at least to the same degree—to the often contrasting results of the voluminous empirical literature on the trade-growth relationship. Some empirical studies of the determinants of economic growth that rely on cross-country regressions have shown that the average effect of globalization on long-run growth is heterogeneous across countries, small, and insignificant. However, other studies have found a positive relationship between trade reforms and growth.2

In first-generation models of endogenous growth the dependence of long-run growth on market size can be traced to the “scale effects” property.3 Jones [12] argued persuasively that this property is inconsistent with post-war time-series evidence which posits an exponential increase in R&D resources and a more-or-less constant rate of per-capita GDP growth in all major advanced countries. Jones’ criticism and researchers’ eagerness to explicitly incorporate the rate of population growth in R&D-based growth models stimulated the development of a second-generation models capable of delivering endogenous growth in the absence of scale effects.4

The 2018-19 global tariff war initiated by the United States, the worldwide pandemic, and the Russian-Ukrainian war have renewed the policy and academic interests in the threats to globalization and intensified the debate on its value.5 Multinational corporations, global supply chains, international conflict, the rise of economic nationalism, and protectionist pressures are controversial aspects of globalization that blur its associated effects. In light of the policy relevance of these issues and the inherent problems with the quality of international data, it is, therefore, imperative for scholars to take a longer-run perspective while at the same time paying closer attention to the economic forces and the complex channels through which the effects of globalization are transmitted. We aim to (partially) address this need by exploring the long-run effects of globalization on growth and the distribution of income within countries, with the help of a Schumpeterian model of endogenous growth.

A notable feature of our model is that it does not suffer from the scale-effects property. However, in contrast to most contributions, we remove this property by following a procedure similar to the one employed in the closed-economy setup developed by Dinopoulos and Syropoulos [23]. Specifically, recognizing the existence of insecurity in intellectual property rights (perhaps due to incomplete/imperfect patent protection), we allow firms that produce state-of-the-art quality products to undertake costly expenditures in activities—which we label rent-protection activities (RPAs)—in order to prolong their temporary monopoly power. More precisely, we suppose that incumbent firms protect their interests by expending real resources to increase their challengers’ difficulty of discovering higher-quality products through R&D effort.6 Examples of such activities include investments in trade secrecy, the camouflage of innovations through technological complexity, the employment of legal teams to litigate potential patent infringements, and patent blocking (i.e., building a patent fence around a major invention by patenting several related secondary inventions without necessarily introducing the latter into the market).7 As discussed below, RPAs are also related to several strands in the literatures on rent-seeking contests, tournaments, and appropriative conflict. Thus, in addition to being empirically relevant, their incorporation in Schumpeterian growth models is compelling and theoretically promising.

In the model, there are two countries, Home and Foreign, that may differ in population size and/or skill abundance. In each country, two primary factors of production, high-skilled and low-skilled labor, are available for production purposes. In any given economy, the supply of every factor is a fixed fraction of an economy’s population, which is assumed to grow at a common and exogenously given rate. Furthermore, there is a continuum of structurally identical industries producing final consumption goods. Within each industry three activities are present: manufacturing of final goods, rent-protection activities (RPAs), and R&D services. Finally, the technology for each activity exhibits constant returns to scale and the provision of positive output or service requires the employment of high- and low-skill labor.8 As we will see, in addition to being analytically tractable, a noteworthy advantage of this framework is that it can capitalize on valuable insights from the traditional factor-proportions theory of international trade to address the issue of income distribution. Equally importantly, by modeling the nuanced interactions among firms as global innovation contests, our framework also helps advance our understanding of the dynamic effects of globalization.

As in quality-ladders of Schumpeterian growth models, the quality of each final good can be improved through endogenous innovation. The arrival of innovations in each industry is governed by a memoryless Poisson process whose intensity (hazard rate) depends on the ratio of R&D services to RPAs. This is the sense, then, that one can view the innovation process we consider as an outcome of sequential and stochastic R&D contests among incumbent and challenger firms (as opposed to R&D races among challenger firms). Of course, the literatures on contests and tournaments are extensive, venerable, and highly pertinent to the problem at hand.9 A noteworthy feature of our paper to these lines of research rests in its consideration of dynamic interactions in the world economy with a focus on its implications for the skill premium and endogenous growth.10

The model allows us to establish several novel findings. First, we show that the growth rate equals the ratio of the unit-cost function of RPAs over the unit-cost function of R&D services. This finding suggests that long-run growth is proportional to the “opportunity cost” of RPAs measured in units of R&D services (i.e., the “relative price” of RPAs). This has interesting implications. For example, an increase in the skill premium (i.e., the relative wage of high-skilled labor) raises the opportunity cost of RPAs (and thus the economy’s growth rate) if and only if high-skilled labor is used more intensively in RPAs than in R&D (Proposition 1). As a consequence, any policy that affects product prices (e.g., trade restrictions) alters the skill premium and, through it, the long-run growth.11 In short, and crucially for our purposes, Proposition 1 provides a formal link between changes in the skill premium and long-run Schumpeterian growth.

Secondly, and armed with Proposition 1, we proceed to analyze the growth effects of globalization which, for simplicity, we capture with a move from autarky to the integrated equilibrium of the world economy.12 In this context, we explore two possibilities. First, we study the effects of globalization when countries differ in population size but not in relative skill abundance. In this case, globalization (or trade openness) generates inter-sectoral trade as each country contains a fraction of quality leaders producing the state-of-the-art quality product and enjoying temporary global monopoly profits at each instant in time. Interestingly, in the absence of scale effects, trade openness does not affect the skill premium and long-run growth (Proposition 4). Trade openness simply redistributes per-capita resources within manufacturing in each country, but does not affect per-capita resources devoted to R&D and RPAs. This result, which we believe remains valid in other models of scale-invariant growth, clarifies the important insight in Dinopoulos and Segerstrom [39] that reciprocal tariff reductions affect the level of scale-invariant growth and income distribution by changing the skill premium.

In the second possibility, we explore the effects of a move from autarky to the integrated equilibrium of the world economy when countries differ in relative skill abundance. Since the three activities (RPAs, R&D and manufacturing) correspond to different vertical stages in production and there is no outside-good sector, in this case, trade in goods alone cannot replicate the integrated-world equilibrium. For this reason, in the presence of inter-country differences in skill abundance, the integrated-world equilibrium generates a rich and realistic pattern of global production. Without loss of generality, we assume that RPAs are high-skilled labor intensive, as compared to the production of R&D services, and manufacturing is the least skilled-labor intensive activity. In this case, as the skill abundance of, say, Home rises relative to the skill abundance of Foreign, the integrated-world equilibrium can be maintained, first, through the formation of Home multinationals that establish manufacturing facilities in Foreign to serve domestic markets locally (horizontal foreign direct investment) or, alternatively, the world market (vertical foreign direct investment). The same equilibrium is consistent with outsourcing of manufacturing production and jobs from Home to Foreign. However, as the skill abundance differential between Home and Foreign increases further, in addition to the formation of multinationals, Home engages in outsourcing of R&D services (i.e., exporting high-tech jobs) to Foreign.

We then examine the effects of globalization under the assumptions that the distribution of national factor endowments lies within the factor price equalization (FPE) set and that Home is skill abundant.13 Under the assumption on the ranking of skill intensities across activities noted above, under autarky skill abundant Home has a lower skill premium than Foreign and experiences a lower long-run growth rate than Foreign (Proposition 1). In this case, globalization ensures the skill premium between the two countries is equalized and their respective long-run growth rates converge to a common global level. As a result, the high-skill abundant country’s growth rate rises while the low-skill abundant country’s growth rate falls (Proposition 5). The opposite occurs if the production of R&D services is more high-skilled labor intensive than the production of RPAs.

Our work complements the seminal studies of Stiglitz [40] and Ventura [41] who analyze the impact of trade on growth and factor prices in the context of the standard Ramsey model of economic growth. In our model, as in the models of these studies, globalization generates factor-price equalization under incomplete specialization in activity production. However, unlike these two studies, our model focuses on Schumpeterian (as opposed to capital-accumulation-based) growth and emphasizes, in this context, the manner in which relative factor endowments condition the effects of globalization on long-run total factor productivity (TFP) growth.

Finally, our work complements a small but important literature on trade and global scale-invariant growth that has been concerned with similar issues, including: Dinopoulos and Segerstrom [39] and Sener [42] who analyze the impact of tariffs on global scale-invariant growth in the context of two identical countries; Krugman [43], Grieben and Sener [44], and Dinopoulos and Segerstrom [45], among others, who develop North-South models of trade and scale-invariant growth—with labor being the only factor of production—to study the effects of globalization on international technology transfers and the North-South wage gap. The present model analyzes the effects of a move from autarky to free trade (as opposed to tariff reductions) on growth and the wage-income distribution within each country (as opposed to the North-South wage gap).

2. The Model

2.1. Overview

In this section, we build a two-country, dynamic general-equilibrium model of scale-invariant growth to study the effects of trade on long-run growth and wage-income distribution. The global economy consists of two countries “Home” and “Foreign”. Consumer tastes are identical across the two countries and each country is populated by a continuum of structurally-identical industries producing final consumption goods whose quality can improve through endogenous innovation.

We model the innovation process as a contest between incumbent global quality leaders and challengers. Each incumbent firm can prolong the expected duration of its monopoly profit by engaging in rent-protection activities (RPAs) that reduce the instantaneous probability of further innovation. At the same time, however, challengers in both countries engage in R&D to discover the next higher-quality product that will replace the global quality leader.14

The analysis proceeds in two steps. First, we develop the steady-state equilibrium of the integrated-world economy. This equilibrium is analytically identical to an autarkic global economy. Second, we introduce country borders by describing how the distribution of global factor endowments between the two countries determines the steady-state pattern of trade and investment.

For expositional claarity, we adopt the following notational conventions. Superscripts h and f identify functions and variables of Home and Foreign countries, respectively. Functions and variables without superscripts are associated with the global economy. Subscripts identify activities and firms within an industry. The time argument indicates that a variable is growing in the steady-state equilibrium; its absence means that the particular variable remains constant over time.

2.2. The Knowledge-Creation Process

The global economy is populated by a continuum of structurally identical industries indexed by . In each industry there are global, sequential and stochastic R&D contests that result in the discovery of higher-quality final products. At time t, each good is produced by an incumbent global monopolist (quality leader) who is targeted by a fringe of challengers. Each challenger k targeting a quality leader in industry engages in R&D aiming at the discovery of the next higher-quality product with instantaneous probability , which is the probability that challenger k will discover the next product at time when the product is not discovered at time t. We assume that the hazard rate is given by

where denotes challenger k’s level of R&D services, and is a function that captures the difficulty of conducting R&D in industry at time t, as in Dinopoulos and Syropoulos [23] and Dinopoulos and Segerstrom [39]. Higher values of imply a lower instantaneous probability of discovering the next higher-quality product for any given level of R&D investment, and capture the empirically-relevant hypothesis that ideas that generate exponential growth are getting harder to find (Bloom et al. [47]).

Under the assumption (routinely adopted in Schumpeterian growth models) that the returns to R&D investment are independently distributed across challengers, countries, industries and over time, the industry-wide global hazard rate of innovation is obtained from (1) by summing the levels of R&D services across all challengers

where . The arrival of innovations in each industry follows a memoryless Poisson process with intensity , which captures the global rate of innovation in a typical industry.

We assume that the difficulty of conducting R&D is proportional to the level of RPAs undertaken by a typical quality leader; that is,

where is the level of RPA services produced by an incumbent global quality leader in industry Parameter () captures the effectiveness (or productivity) of RPAs in increasing the difficulty of conducting R&D. One can think of as capturing the efficiency of institutions or the secrecy that safeguards intellectual property. These institutions may include alternative patent regimes, membership in international agreements or organizations that protect intellectual property, the length and breadth of patents granted by a government, revocation of patents, and compulsory licensing of technology.15

Equations (2) and (3) reveal that the instantaneous probability of discovering the next higher-quality good is proportional to the relative price of RPA services expressed in units of R&D services. These equations also imply that, if an incumbent monopolist does not engage in RPAs, the discovery of the next higher-quality product occurs instantaneously because . In addition, for any finite level of R&D services the innovation process stops if .

2.3. Production Technology

There are three distinct activities in each industry: manufacturing of final products, rent-protection services, and R&D services. The technology of each activity exhibits constant returns to scale (CRS) and requires the employment of two factors of production, high-skilled and low-skilled labor. Let and respectively denote the steady-state wages of high-skilled and low-skilled labor. Moreover, note that , and the level of RPAs, R&D services, and manufacturing output of the final good produced in industry , respectively. The technology for each of the three activities is described by the cost function

where is the level of output related to activity and is the associated unit-cost function. We assume that unit-cost function is increasing, concave, and homogeneous of degree one in its arguments. We also assume that the production technology captured by these unit cost functions is the same across countries, industries and goods of different quality levels.

Shephard’s Lemma implies that the per unit of output factor requirements in activity A can be obtained by differentiating each unit-cost function with respect to its argument; that is,

where denotes the relative wage of high-skilled workers (skill premium). Expression () is the amount of high-skilled (low-skilled) labor required to produce one unit of activity . The assumption of CRS technologies imply that each unit-factor requirement is homogeneous of degree zero in factor prices which in turn allows us to write it as a function of the skill premium . Concavity of and CRS imply that and . One can now define the skill intensity of activity as

where is the ratio of high-skilled to low-skilled labor in activity A. Because the numerator of (6) falls and the denominator rises with increases in , the skill intensity of each activity is decreasing in the skill premium ().16

2.4. Households

The global economy is populated by a continuum of identical households of measure . Each household consists of infinitely-lived members and is modeled as a dynastic family whose size grows over time at an exogenous rate . The global population, as well as the number of each household’s members, at time t is , where is the initial population at time . This formulation implies that the population, which is partitioned into high and low-skilled workers, grows at a common, constant, and exogenously given rate .

In order to keep the analysis as simple as possible, we assume that each worker supplies one unit of labor and that a (fixed) fraction of the population consists of high-skilled workers with the remaining fraction consisting of low-skilled workers.17 Consequently, the world economy’s (i.e., the global) endowment of high-skilled labor is , and the global endowment of low-skilled labor is . Over time, both endowments grow exponentially at the rate ; that is,

Every household maximizes the discounted utility

where is the subjective discount rate, is the effective discount rate, and is the per-capita instantaneous utility function at time t. The latter function takes the form

where is the quantity consumed of a good of quality i (i.e., a product that has experienced i quality improvements) that is produced in industry at time t. Parameter (>1) measures the size of quality improvements (i.e., the magnitude of each innovation).

At each instant in time, each household allocates income to maximize (9) taking product prices as given. The solution to this maximization problem yields a global Cobb-Douglas demand function

where is per-capita consumption expenditure and is the relevant market price for each good. Because goods adjusted for quality are by assumption identical within each industry [see (9)], only the good with the lowest quality-adjusted price is consumed as there is no demand for any other good.18 In addition, the RHS of Equation (10) implies that the demand for each final good is the same across all industries.

Maximizing (8), subject to the standard inter-temporal budget constraint and taking into account (10), generates the standard differential equation that governs the evolution of per-capita consumption expenditure

where is the instantaneous market interest rate that prevails at time t. Equation (11) implies that a constant per-capita consumption expenditure is optimal when the instantaneous interest rate equals the consumer’s subjective discount rate .

2.5. Innovation Contests

At each instant in time, a typical industry is served by a quality leader, the only global producer of the state-of-the-art quality product. This producer is targeted by challengers from both countries who engage in R&D to discover the next higher-quality product that will replace the incumbent technology leader. The latter enjoys temporary global monopoly profits and spends resources on rent protection activities (RPAs) in order to prolong its market position. In other words, RPAs aim to protect incumbent profits and constitute a barrier to innovation and economic growth. We assume that firms compete in prices in product markets and take actions aimed at maximizing their respective expected discounted profits. The difference is that each incumbent quality leader chooses optimally its level of RPAs whereas each challenger chooses its level of R&D. Challengers keep entering each innovation contest until expected discounted profits associated with R&D are driven down to zero.

The arrival of innovations in each industry is governed by a Poisson process with intensity , which depends on R&D services and RPAs and thus can be analyzed as a global innovation contest. We model the strategic interactions between a typical incumbent and its challengers as a differential game for Poisson jump processes. Dinopoulos and Syropoulos [23] solve this stochastic differential game formally. In this paper, we provide an informal and intuitive derivation of the equilibrium conditions that closely follows the methodology employed by Schumpeterian growth models.

At each instant in time, a global quality leader produces the state-of-the-art quality product and earns a flow of profits

The last term in (12) captures the cost of RPAs incurred by an incumbent quality leader in industry at time t. As in Dinopoulos and Segerstrom [39], we assume that all firms in the world have access to the technologies of products that are one or more steps below the highest-quality available good in each industry. This assumption prevents the incumbent monopolist from engaging in R&D to discover the next higher-quality product. Thus, we adopt an extreme version of the patent “commons” practice, according to which a company allows free access to its patented technology in order to allow other firms to improve upon existing products without facing infringement risks.19 In short, at each point in time, each challenger invests in R&D to discover the higher quality product and each incumbent quality leader engages in RPAs to prevent challengers from replacing it.

There is a global stock market that supplies consumer savings to firms engaged in R&D. Since there is a continuum of structurally identical industries, each consumer can diversify completely the industry-specific risk associated with the discovery of new products. In addition, each investor can hold a portfolio of domestic and foreign stocks. This implies that the market interest rate is equal to the rate of return offered by a completely diversified portfolio. At each instant in time, each challenger issues securities promising to pay the flow of global monopoly profits (divided by the number of shares) if the firm wins the innovation contest and zero otherwise. The money earned from the sale of these securities is equal to the wage bill of high-skilled and low-skilled workers engaged in R&D. Moreover, at each instant in time, there are two types of securities in the stock market: those issued by challengers and those issued by incumbents who have won R&D contests.

Consider now the stock-market valuation of temporary monopoly profits earned by an incumbent quality leader. Denote with the expected global discounted profits of a successful innovator in industry and let be the industry’s global rate of innovation. Given that is the industry’s hazard rate, a shareholder faces a capital loss equal to if further innovation occurs at time . This event occurs with instantaneous probability . In addition, over an infinitesimal time interval , the shareholder receives a dividend and the value of the quality leader’s stock appreciates by if the incumbent quality leader is not replaced by the end of time interval The incumbent’s survival probability is given by .

The absence of profitable arbitrage opportunities implies that the expected rate of return on a stock issued by a successful innovator must equal the market interest rate payments ; that is,

Dividing both sides of this equation by , taking limits as , and solving for the stock-market valuation of monopoly profits yields

where the flow of monopoly profits is defined by (12).

Let us now consider the economic problem of a typical challenger k targeting a quality leader in industry Challenger k’s expected discounted profits are equal to

where is the reward to R&D (the expected discounted monopoly profits associated with a successful innovation), is the instantaneous probability of discovering the next higher-quality good, and the last term is the cost of R&D services over an infinitesimal period of time . In words, by incurring R&D costs during period , challenger k wins the contest at the end of period with probability and receives prize . With instantaneous probability challenger k loses the innovation contest and receives a zero prize.

Free entry into each R&D contest drives a challenger’s expected discounted profits down to zero, thereby resulting in the following zero-profit condition:

Equation (14) states that the price of innovation adjusted for the difficulty of conducting R&D, which is proportional to the level of rent-protection activities, equals the unit cost of conducting R&D.

We now proceed to analyze the maximization problem of a successful global quality leader facing challengers from both countries. The incumbent chooses the price of its product and the level of RPAs to maximize its expected discounted profits in (13). When maximizing (13) the global quality leader behaves as a Nash competitor (i.e., it takes each challenger’s actions and the growth rate of expected discounted profits as given). The assumptions that goods within an industry are identical (when adjusted for quality) and product markets are characterized by Bertrand price competition imply that each quality leader engages in limit pricing. In addition, the absence of trade barriers together with the assumption that the technology of all products with lower quality than the state-of-the-art product in each industry is public knowledge imply that the quality leader charges a single price, which is times the manufacturing cost (i.e., the lowest possible price of the product one step below in the quality ladder); that is,

Maximizing (13) with respect to the level of RPAs, , yields the following condition:

In the steady-state integrated-world equilibrium, factor prices and are equalized internationally and are constant over time. Furthermore, all per-capita variables are constant over time and the structural symmetry across industries allow us to drop argument from all industry-specific variables. These long-run properties enable us to improve the exposition by simplifying the model’s notation.20

Incorporating these properties in (13) yields the standard expression for the steady-state value of innovation

where the steady-state monopoly profit level = grows at the rate of population growth

One can derive a deterministic expression for the instantaneous per-capita utility in the integrated-world equilibrium. Substituting per-capita demand for final consumption goods , where , into (9) yields.21

Subutility captures the appropriate quality-adjusted real consumption index.22 The economy’s per-capita long-run growth can be defined as the growth rate of subutility in (17). Differentiating (17) with respect to time delivers

Because the quality increment () is a parameter capturing the size of innovations, long-run growth can be affected only through changes in the rate of innovation .

Equation (15) relates the rate of innovation to the relative price of rent-protection activities. In addition, Equation (14) implies that the relative price of innovation equals the unit cost of R&D. Combining these two profit-maximizing conditions yields

where, as noted earlier, is the skill premium. The last equality follows from the linear homogeneity of unit cost functions in factor prices.

Equation (19) is the dual of (2) and provides one of the noteworthy insights of this paper: the innovation rate is proportional to the “relative price” or, more precisely, the opportunity cost of RPAs expressed in units of R&D services. Thus, the removal of scale effects in the model sets comparative-advantage forces (captured by opportunity costs) at center stage thereby preparing the ground for our analysis of the relationship between globalization and scale-invariant growth. In addition, Equation (19) implies that the steady-state of the rate of innovation is identical across industries and constant over time; that is, . Finally, observe that the long-run rate of innovation is fully endogenous and can be affected by any policy that alters the skill premium. As such, it provides a novel link between the functional distribution of income and fully endogenous long-run growth, as indicated by Equations (18) and (19).

Because we are interested in the impact of globalization on long-run Schumpeterian growth, it is useful to establish the precise channel through which a change in the skill premium affects the rate of innovation . Taking logs, differentiating (19) with respect to the skill premium and multiplying both sides of the resulting equation by gives

where captures the relative-wage elasticity of the innovation rate, and is the cost share of high-skilled labor in activity .

Equation (20) introduces the innovation version of the celebrated Stolper-Samuelson [38] theorem that relates changes in factor prices to changes in commodity prices. Henceforth, we assume the absence of skill-intensity reversals; that is, we assume that the ranking of factor shares and remains intact (i.e., it does not get reversed) at all feasible values of . We thus arrive at

Proposition 1.

In the absence of skill-intensity reversals, an increase in the skill premium ω raises the economy’s rates of innovation and growth if and only if the production of rent-protection activities is more skill intensive than the production of R&D services (i.e., iff ).23

The intuition behind Proposition 1 is straightforward. If the production of RPAs is more skilled-labor intensive than the production of R&D services, an increase in the skill premium raises the unit cost of RPAs more than the unit cost of R&D services . Thus, relatively more costly RPAs encourage the production of R&D services resulting in higher rates of innovation and growth.24

The remaining of this subsection establishes the determination of skill premium as a function of model parameters and characterizes the model’s comparative steady-state properties. Let , and be the per-capita world levels of RPAs, R&D services, and final consumption good respectively.25 The per-capita full-employment condition of high-skilled labor is given by

where is the constant share of high-skilled labor in the global economy and is the unit high-skilled labor requirement in activity . The left-hand-side (LHS) of (21) equals the per-capita supply of high-skilled labor whereas the right-hand-side (RHS) equals the sum of the demands for high-skilled labor in RPAs, R&D services, and manufacturing. The full-employment condition of low-skilled labor in per-capita terms is similarly defined to be

where is the economy’s share of low-skilled labor, and is the unit low-skilled labor requirement associated with activity .

Appendix A provides the algebraic details on the derivation of the following equation that determines the general-equilibrium solution to the skill premium ():

where the LHS equals the world’s skill abundance (global relative supply of high-skilled labor) since . Because and are proportional to the world level of population, , both of them grow at the rate of population growth . As a result, the world economy’s skill abundance remains constant over time. The RHS of (23) is the global relative demand for high-skilled labor.

In what follows, we focus on the case in which the relative demand for high-skilled labor is a decreasing function of the skill premium (i.e., the relative demand curve for high-skilled labor is downward-sloping). As formally shown in Appendix A, Assumptions 1 and 2 below identify sufficient conditions that ensure this property.

Assumption 1:

The skill intensities of rent protection (X), R&D (Y), and manufacturing (Z) activities are ranked as for all feasible levels of the skill premium ω.

Assumption 1 states that manufacturing of the final consumption good is less skill intensive than the skill intensities of the other two (investment-related) activities, which seems natural.26 As in the standard static factor-proportions theory, Assumption 1 rules out factor-intensity reversals and is needed for the comparative steady-state analysis.

Assumption 2:

The elasticity of substitution between high-skilled labor and low-skilled labor in the production of RPAs, R&D, and manufacturing is greater than or equal to unity.

Assumption 2 ensures that the high-skilled labor cost share in every activity is a non-increasing function of the skill premium; that is, high-skilled and low-skilled labor are gross substitutes.27 Once again, we formally establish that the RHS of (23) is decreasing in in Appendix A.28

The following proposition establishes the existence of a unique steady-state integrated-world equilibrium.

Proposition 2.

The integrated-world economy has a unique steady-state equilibrium in which: (a) the rate of innovation I, the interest rate r, per capita consumption expenditure c, the skill premium ω, per-capita RPAs x, and per-capita R&D investment y, are all constant and bounded over time; (b) long-run Schumpeterian growth is fully endogenous.

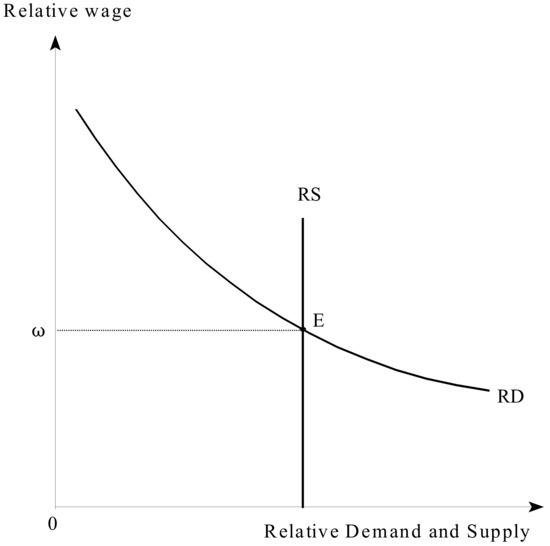

Any policy that affects the skill premium (i.e., an R&D subsidy, a wage subsidy, or a tariff) has a permanent impact on the long-run rates of innovation and growth. Figure 1 illustrates the steady-state integrated-world equilibrium by plotting the relative supply and relative demand curves for high-skilled labor. The relative supply curve corresponds to the LHS of (23) and is captured by the perfectly inelastic curve labeled RS. The relative demand curve corresponds to the RHS of (23) and is negatively-sloped curve labeled RD. The unique intersection between the two curves at point E determines the steady-state value of skill premium . Once the equilibrium skill premium is determined, the rest of the model’s endogenous variables are determined as well.

Figure 1.

Steady-State Integrated-World Equilibrium.

In the absence of population growth (i.e., ), the integrated-world economy experiences positive and fully endogenous Schumpeterian growth. In contrast, a class of semi-endogenous Schumpeterian growth models (Jones [56], and Segerstrom [57], among others) yields zero long-run growth if the economy’s population is not growing. Consequently, the present model represents a novel generalization of first-generation endogenous-growth models.

Proposition 1 and Figure 1 can be employed to perform standard comparative steady-state exercises. For example, an increase in the growth rate of population , or the size of innovations shifts curve RD to the right, raises the equilibrium skill premium , and accelerates long-run Schumpeterian growth rate . The following proposition summarizes the model’s comparative steady-state properties.

Proposition 3.

Under Assumptions 1 and 2, long-run innovation and scale-invariant Schumpeterian growth: (a) increase in the rate of population growth and the size of innovations λ; and (b) decrease in the subjective discount rate ρ, the efficiency of RPAs δ, and the economy’s skill abundance .

An economy with higher skill abundance is characterized by lower skill premium (this is purely a supply-side effect), but the effects of a higher skill premium on growth are ambiguous and depend on the skill intensity ranking between RPAs and R&D. Assumptions 1 and 2 imply that a higher skill premium generates faster rates of innovation and growth. This is so because the opportunity cost of R&D services is “cheaper” than that of RPAs in economies with higher skill premium , which corresponds to a lower global skill abundance as illustrated in Figure 1.

2.6. National Labor Markets

We assume that wages are perfectly flexible so that, as a result, the market for each type of labor clears instantaneously. Consider the integrated-world equilibrium and denote with superscript j variables and functions associated with country , where h refers to Home and f refers to Foreign. In order to derive the high- and low-skilled labor full-employment conditions, one must calculate the steady-state distribution of Home and Foreign quality leaders across the continuum of industries.

Let be the steady-state fraction (measure) of industries with a Home quality leader and the fraction of industries with a Foreign quality leader. Since each industry is targeted by challengers in the global economy, a Home challenger, for example, which targets a Foreign quality leader in industry discovers a higher quality product with instantaneous probability . This event transforms industry into an industry with a Home leader. Structural symmetry across industries implies in the steady-state equilibrium, so the steady-state hazard rate of innovation is identical across industries and constant over time. In addition, since there are industries with Foreign quality leaders, the flow of industries that are transformed into industries with a Home quality leader satisfies . Moreover, in the steady-state equilibrium, this flow must be equal to the flow of industries with Home quality leaders that are transformed into industries with Foreign quality leaders . Therefore for .

The supply of high-skilled labor in country j is . The demand for high-skilled labor consists of three components. First, there are quality leaders in country j with each leader supplying the global market units of final output. But each unit of output requires units of high-skilled labor, as indicated in (5). Therefore the demand for manufacturing labor in country j is . Second, the demand for high-skilled labor in rent-protection activities is . This is so because there are quality leaders located in country j, each of which produces units of RPAs, with each unit requiring units of high-skilled labor. Third, the demand for high-skilled labor in R&D in each industry in country j is . All industries are targeted by challengers, each industry produces units of R&D services, and is the associated unit high-skilled labor requirement. Because each economy has a continuum of structurally identical industries of measure one and all industries are targeted by challengers everywhere, it follows that the demand for high-skilled labor in each industry equals the economy-wide demand for R&D services in country j. It follows that the per-capita full-employment condition of high-skilled labor in country j is

Calculations similar to the derivation of (24) generate the following per-capita full-employment condition of low-skilled labor in country j:

The above four full-employment conditions hold at each instant in time under the assumption that there is free trade in final goods but no multinational production and/or outsourcing of RPAs and R&D services. We relax this assumption in Appendix B. Equations (24) and (25) complete the description of the model.

3. The Growth Effects of Globalization

The previous section established the existence of a unique steady-state equilibrium for the integrated-world economy. The autarky equilibrium of country can be obtained by substituting for s in the full-employment of labor conditions (21) and (22). These two benchmark equilibria will be used to analyze the effects of globalization captured by a move from autarky to the integrated-world equilibrium. Depending on the distribution of per-capita factor endowments between the two countries, the integrated-world equilibrium is characterized with intra-sectoral (R&D-based) trade, multinational firms, outsourcing of R&D services, and factor price equalization. Appendix B provides a complete characterization of this rich production pattern which is consistent with factor-price equalization.29

First, we consider the case in which the two countries are identical in all respects except their population sizes. We then examine the more general case in which Home and Foreign differ in skill abundance. We use the phrase “a move from autarky to the integrated-world equilibrium” loosely to imply that we consider a comparison between two structurally identical economies with one economy being in the autarkic steady-state equilibrium and the other in the integrated-world steady-state equilibrium. In other words, we abstract from analyzing the transitional dynamics from autarky to the integrated-world equilibrium.

3.1. Trade Openness

We illustrate the first case with the help of Figure 1. Although in this case countries can differ in size, they do not differ in skill abundance; that is, and , where , while . As a result, the relative supply of high-skilled labor in each country coincides with that of the integrated-world economy; that is, . In this case, Equation (23) describes both the autarkic and integrated-world equilibria, and each country’s relative supply curve coincides with RS in Figure 1.30 Further, both countries grow at the same rate and have the same autarkic skill premium , regardless of their exact population-size differences. Thus, a move from autarky to the integrated-world equilibrium does not affect the long-run rates of innovation and growth in either country.

Nonetheless, globalization generates intra-sectoral trade between Home and Foreign. This is so because a fraction of industries are populated by country j’s quality leaders which enjoy temporary global monopoly power and serve consumers in both Home and Foreign. In the absence of multinational firms, each industry experiences random shifts in the location of production, and resources devoted to exports and imports in each country grow at the rate of population growth.

Proposition 4.

Suppose that Home and Foreign differ only in size measured by their respective population levels. Trade openness generates intra-sectoral trade and does not affect long-run Schumpeterian growth .

Proof.

It follows from Figure 1 and Proposition 1. □

The intuition behind Proposition 4 can be clearly demonstrated in the case of two structurally identical economies, where , as in Rivera-Batiz and Romer [2,3], and Dinopoulos and Segerstrom [39], where and . In this case, a move from autarky to free trade results in each country having quality leaders in fifty percent of all industries. There is a resource reallocation from import competing to exporting industries in each country, but because the number of consumers served by each quality leader is twice as large as the number of consumers served in autarky, the introduction of trade does not change per-capita resources devoted to R&D and RPAs. Thus, the removal of scale effects also removes the market-size impact of international trade that was discovered and discussed extensively in first-generation Schumpeterian growth models (Grossman and Helpman [4] Chapter 5; Dinopoulos et al. [5]; Rivera-Batiz and Romer [2,3]).

3.2. Multinational Firms

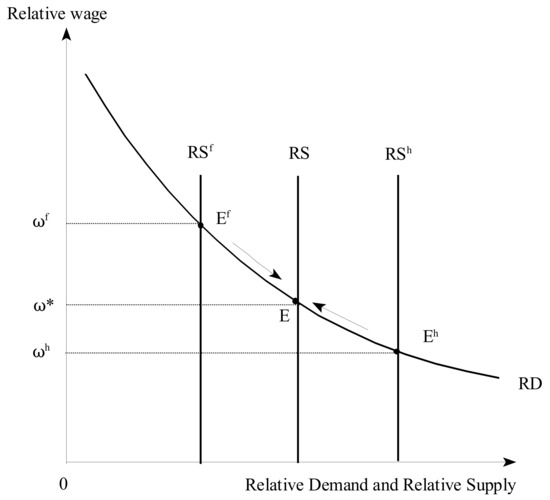

The second case focuses on the effects of globalization on the skill premium and long-run growth, when countries differ in skill abundance. Figure 2 illustrates this case, under the assumption that Home is skill-abundant (). Since this assumption implies that Home’s relative supply of high-skilled labor is located to the right of Foreign’s relative supply and both countries face the same downward-sloping relative demand curve , Home’s skill premium in autarky is lower than Foreign’s skill premium (i.e., ). Therefore, a move from autarky to the integrated-world equilibrium causes Home’s skill premium to rise from to and Foreign’s skill premium to fall from to . At the integrated-world equilibrium, both countries enjoy the same rate of long-run growth.

Figure 2.

Trade and Relative Wages.

Given our assumptions on no skill-intensity reversals (), Home’s Schumpeterian long-run growth is lower than Foreign’s at the initial equilibrium. In this case, globalization raises Home’s growth and reduces Foreign’s growth.31

Appendix B analyzes the production patterns that are consistent with the integrated-world equilibrium in this case, where countries differ in skill abundance. First, if the distribution of per-capita factor endowments is located inside triangle in Figure A1, say point , the integrated-world equilibrium can be obtained with the formation of Home-based multinational companies. Each Home quality leader either produces a fraction of the output of the final good in Foreign (horizontal multinationals) or a fraction of Home quality leaders manufacture all final output in Foreign (vertical multinationals). This equilibrium emerges when there is a relatively moderate difference in skill abundance between Home and Foreign.

Finally, consider the case where the difference in skill abundance between the two countries is relatively high such that the allocation of per-capita factor endowments is located inside triangle in Figure A1. In this case, all Home quality leaders manufacture their final-good output in Foreign, and a fraction of Home quality leaders produce R&D services in Foreign. In other words, the integrated-world equilibrium is consistent with outsourcing of R&D services from Home to Foreign.

Proposition 5.

Suppose that the two countries differ in skill abundance. Under Assumptions 1 and 2, globalization leads to: (a) the equalization of long-run Schumpeterian growth between the two countries; (b) a rise in the long-run Schumpeterian growth of the high-skilled abundant country and a fall in for the low-skilled abundant country; and (c) the formation of multinationals and outsourcing of R&D services by the skill-abundant country.

3.3. Discussion

The prediction of factor price equalization, despite apparent total factor productivity differences (captured here by aggregate quality differentials) across the two countries, is consistent with several empirical studies following Trefler’s [58,59] seminal work. These studies have found that factor-price equalization across countries holds when production factors are adjusted for uniform productivity differences. As already emphasized, Proposition 1 offers a novel link between relative wages and long-run growth and thus ties long-run growth to the functional distribution of income captured by the skill premium. The main result of Proposition 5 complements and clarifies the finding of Dinopoulos and Segerstrom [39] where trade liberalization in the form of reciprocal tariff reductions between two countries with identical endowments and sizes generates growth effects. In both cases, scale invariant growth is affected by policies that change the relative price of innovation and/or relative factor prices. In the present model countries differ in factor endowments and therefore the long-run rates of innovation move in opposite directions, whereas in Dinopoulos and Segerstrom [39] the two countries are structurally identical and, as a result, national rates of innovation move in the same direction.

The main findings regarding the effects of globalization on long-run growth, which are summarized in Propositions 4 and 5, shed light to several empirical findings. A number of studies have documented low (or statistically insignificant), and even negative values of coefficients that measure economic openness in cross-country growth regressions.32 However, these studies do not control for factor abundance differences across countries and factor intensities of activities associated with manufacturing and investment services. Nonetheless, their reported empirical results are consistent with the present model that predicts convergence of factor prices and long-run growth rates of total factor productivity (TFP) which is a necessary condition for per-capita income convergence among trading countries. The present study provides indirect theoretical support for the above findings by establishing the conditions under which globalization and long-run TFP growth are complements or substitutes and by shedding light on the nexus among globalization, growth and the skill premium.

4. Concluding Remarks

Our primary objective in the paper is to formally identify the salient channels through which globalization affects the skill premium and long-run Schumpeterian growth in the context of a two-country dynamic general-equilibrium model. A key feature of our approach is that our consideration of rent-protection activities (RPAs) removes the scale-effects property while preserving the policy endogeneity of long-run growth. Interestingly, in our model, growth turns out to be proportional to the opportunity cost of RPAs, measured in units of R&D services, and depends only on factor prices. The absence of scale effects generates fully-endogenous long-run Schumpeterian growth that is bounded and remains constant over time even when the economies experience positive population growth.

The removal of scale effects has profound implications for the literature concerned with the effects of trade on long-run growth. Unlike first-generation models of endogenous growth, which have emphasized the positive impact of market-size expansion on growth, the absence of scale effects in our setting neutralizes the market-size trade-related effect on growth. As a consequence, a move from autarky to free trade between two growing economies that differ only in population size does not affect long-run growth. In this case, there is reallocation of per-capita resources in manufacturing of final goods within each country and globalization generates intra-sectoral trade as a fraction of Home quality leaders become global quality leaders while the rest are replaced by Foreign quality leaders producing superior quality products. This type of resource reallocation does not affect factor prices and per-capita allocation of resources between RPAs and R&D. Consequently, trade openness among countries with identical factor abundance does not have any impact on long-run Schumpeterian growth in any country.

In this paper, we also analyze how cross-country differences in skill abundance shape the effects of globalization on the skill premium and on long-run growth. In this case, a move from autarky to the integrated-world equilibrium generates convergence of national long-run growth rates and international factor price equalization. However, the direction of change in each country’s growth rate depends on countries’ ranking of skill abundance and the ranking of skill intensities between RPAs and R&D services. For example, if Home is skill abundant and RPAs are more skill intensive than R&D services, Home has a lower skill premium and grows more slowly than Foreign under autarky. Globalization equalizes the growth rates in both countries by causing Home’s (resp., Foreign’s) skill premium and growth rate to rise (resp., fall). The integrated-world equilibrium is consistent with a rich production pattern including intra-sectoral trade, the formation of vertical or horizontal multinationals and outsourcing of R&D services or RPAs. This production pattern is similar to the one analyzed by first-generation models of Schumpeterian growth but, of course, as emphasized earlier, these models suffer from the problematic scale-effects property.

The analysis and insights of this paper have several interesting implications for the empirics of R&D-based growth in open economies. The model provides a novel explanation for the absence of a strong positive correlation between measures of trade openness and growth in cross-country regressions. In a global economy experiencing scale-invariant Schumpeterian growth, trade in high-tech industries among countries with similar factor endowments has a minimal (if any) effect on long-run growth. Furthermore, higher levels of globalization among countries with differing proportions in factor endowments is associated with slower or faster long-run growth, depending on whether or not a country is high-skilled or low-skilled labor abundant relative to the skill abundance of the global economy, and on the ranking of skill intensities across various production activities. Without controlling for differences in skill intensities across activities and skill abundance across countries, cross-country growth regressions generate a weak correlation, if any, between measures of globalization and long-run growth.

Our analysis can be extended across several directions. For example, one could analyze the case where the distribution of factor endowments across countries is located outside the factor-price equalization set (which would, in turn, generate differences in relative factor prices and long-run rates of innovation across countries). One could also consider policy instruments such as tariffs and R&D subsidies to explore the effects of trade and industrial policies on economic growth. These potentially fruitful directions of research are beyond the scope of this paper, however, and must necessarily be left for future research.

Author Contributions

E.D., C.S. and T.T. contributed equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Derivation of Equation (23)

Equation (10) and limit-pricing condition imply that, in the steady-state integrated-world equilibrium, per-capita final output z equals

Equations (2) and (3) imply that . In addition, structural symmetry across all industries allows us to focus on the symmetric equilibrium where each global quality leader devotes the same level of per-capita RPAs in each industry . Combining this expression with (19) yields

Equation (A2) implies that per-capita R&D services y is time invariant and equal across industries. Substitute (3) and (13) into (14) to generate

Substitute (3) and (14) into (16) and divide the resulting equation by to obtain the following expression for per-capita monopoly-profit flow

Solve (A3) for c and substitute the resulting expression into (A2) to obtain the following expression for per-capita manufacturing output z:

where (A2) was used to express the rate of innovation as a function of the relative wage of high-skilled labor .

Substitute (A2) and (A5) into full-employment conditions (21) and (22) to obtain

where is the cost share of high-skilled labor in activity .

Assumptions 1 and 2 provide sufficient conditions for the downward-sloping property of relative demand RD. The proof proceeds in two steps. First, express the share of high-skilled labor in the unit-cost of activity A as , where skill intensity is defined in (6). Differentiate with respect to the skill premium to get

where is the elasticity of substitution between high-skilled and low-skilled labor in activity A. As a result, . Equation (A9), Assumption 1 and Proposition 1 establish that the numerator of (A8) decreases with

Second, Equation (A9) implies that the share of low-skilled labor in the cost per unit of activity A, which equals , increases with skill premium . In addition, differentiate expression with respect to to obtain

Consequently, the denominator of (A8) increases monotonically with ; and therefore the relative demand of high-skilled labor RD decreases with the skill premium.

Appendix B

Patterns of Production in the Integrated-World Equilibrium

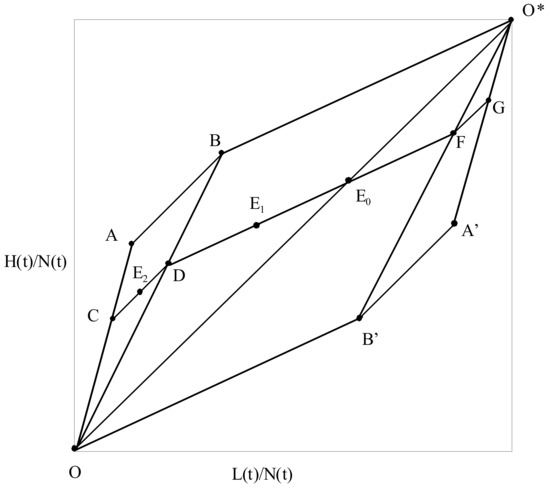

Figure A1 illustrates the per-capita factor-price equalization (FPE) set of the integrated-world economy. As said, the FPE set is defined as the set of all per-capita factor endowment allocations between the two countries such that each country can fully employ its resources using the integrated-world equilibrium skill intensities of each activity. The diagonal of the box diagram corresponds to the per-capita vector of high-skilled and low-skilled labor , , respectively. Vectors , , and represent the per-capita levels of high-skilled and low-skilled labor employed in the production of rent-protection services, R&D services, and manufacturing of final goods. The slopes of these vectors reflect Assumption 1 under which the skill intensity of RPAs is the highest, followed by the skill intensity of R&D services, which in turn is higher than that of manufacturing (i.e., ). The FPE set is represented by the area inside hexagon . Points O and represent the origins of Home and Foreign. The slope of diagonal equals the world skill abundance .

Figure A1.

Production Patterns in the Integrated-World Equilibrium.

Consider first the case where per-capita allocation of the two factor endowments between Home and Foreign is given by point which lies on the diagonal of the box diagram. In this case, the two countries have identical skill abundance ratios which equal to the slope of the box’s diagonal (that is, . The fraction of industries with Home quality leaders is given by .

By drawing vectors , , and that are parallel to vectors , and , respectively, one could illustrate the per-capita quantity of resources devoted to each of the three activities by each country. For example, Home’s per-capita endowment vector is , where vectors , and correspond to the level of Home resources devoted to the production of rent-protection activities, R&D services, and manufacturing of final goods. This allocation of resources is consistent with the per-capita version of Home’s full employment conditions as indicated by (24) and the activity-specific production techniques of the integrated-world equilibrium. To see this observe that triangle is similar to triangle , and triangle is similar to triangle . This implies that ratios are equal to the fraction of Home quality leaders . In other words, Home’s share of resources devoted to each activity equals which in turn equals Home’s share of world R&D services in each industry. Similar reasoning applies to Foreign, whose per-capita factor endowment vector is given by . Foreign’s per-capita resources account for a fraction of each activity which equals its share of world R&D in each industry.

For any allocation of factor endowments between Home and Foreign along diagonal , which is illustrated by a point such as , international trade in final consumption goods suffices to equalize factor prices and thus long-run growth rates between the two countries.33 This equilibrium is characterized by intra-sectoral trade: at any instant in time, a fraction of all industries is populated by Home global quality leaders. Each quality leader produces RPAs, R&D services and the state-of-the-art quality good at Home and serves Foreign consumers through exports. Similarly, a fraction of industries is populated by Foreign quality leaders who serve Home consumers through exports of final goods. The pattern of trade in each industry switches randomly as a result of industry-specific stochastic innovation contests.

Consider next the case where skill abundance differs between the two countries and the point that determines the allocation of per-capita factor endowments lies inside triangle such as point in Figure A1. In this case, the integrated-world equilibrium can be obtained with the formation Home-based multinational companies. Home devotes resources (high-skilled and low-skilled labor) to RPAs, resources to R&D services, and has quality leaders in industries, as in the previous case. However, it can devote only resources to the production of final consumption goods. The integrated-world equilibrium can be replicated if Home quality leaders devote resources in the production of final consumption goods by hiring resources at Home and resources at Foreign. One possible pattern of multinational production that is consistent with this equilibrium is for each Home quality leader to produce at Foreign a fraction of final-product output equal to : this interpretation is consistent with formation of horizontal multinationals (these firms produce the same product at Home and Foreign to serve the domestic market). Another symmetric pattern of multinational production is that a fraction of Home quality leaders transfers all their production of final output to the Foreign country: this is the case of vertical Home multinationals that engage in RPAs at Home, manufacture all output in Foreign and export from Foreign to Home. Of course, since there is a continuum of industries, both patterns of multinational production can coexist. The production pattern of Foreign quality leaders remains the same as the one analyzed in the previous case (associated with point ).

Finally, consider the case where the point that determines the allocation of per-capita factor endowments between the two countries lies inside triangle , such as point in Figure A1. This case corresponds to higher differences in skill abundance between Home and Foreign compared to the case associated with point . All manufacturing of Home final-goods takes place in the Foreign country, and the Home country transfers a fraction of R&D services to Foreign country as well. In other words, the model generates outsourcing of R&D services (i.e., the establishment of Home-owned R&D labs at Foreign), multinational production, and trade in final consumption goods.34 Therefore, the integrated-world equilibrium is consistent with a rich pattern of production which depends on skill-abundance differences between the two countries and skill-intensity differences across production activities: as the difference in skill abundance between the two countries increases, the skill abundant country transfers the production of skill-intensive activities to the less skill abundant country through the formation of multinationals and R&D outsourcing.

Notes

| 1 | The term Schumpeterian growth refers to a particular type of R&D-based (exogenous or endogenous) long-run growth generated through the introduction of new products or processes according to Schumpeter’s [1] description of the process of creative destruction. |

| 2 | For example, in their survey of more that 30 such studies, Lewer and Van den Berg [6] report that about 9 percent of cross-sectional and more than 15 percent of time-series growth regressions find a negative or non-significant correlation between trade and growth. In his more recent survey of studies of trade reforms in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Irwin [7] affirms the heterogeneity of the effects of these reforms on economic growth across developing countries. However, he also concludes that this effect is positive. |

| 3 | Influential models of this type include the ones developed by Aghion and Howitt [8], Grossman and Helpman [9], Romer [10], and Segerstrom et al. [11]. |

| 4 | See Dinopoulos and Thompson [13], Jones [14], Dinopoulos and Sener [15], and Jones [16] who provide overviews of this class of growth models. |

| 5 | Amiti et al. [17] and Fajgelbaum et al. [18] describe the evolution of the 2018-19 trade war and analyze its economic effects. Marioti [19] offers an overview of the global economic consequences of the Russian-Ukrainian war. See also Stiglitz [20] and Bhagwati [21] who provide influential overviews of, as well as valuable reflections on, the pros and cons of globalization. Morgan et al. [22] discuss, among other things, geopolitical types of stress on globalization through policymakers’ widespread reliance on economic sanctions as tools of foreign policy. |

| 6 | A famous case of contested innovation (in which incumbent firms managed to suppress the introduction of a higher-quality product) is Tucker 48. This was an automobile invented by Preston Tucker in 1948 that had better safety and speed features than existing models. In 1949, after producing 50 cars, the company was forced to declare bankruptcy due to negative publicity initiated by the news media, a Securities and Exchange Commission investigation, and a heavily publicized stock fraud trial with unproven allegations. Tucker claimed that the Big Three automakers and Michigan Senator Homer S. Ferguson played instrumental roles in the Tucker Corporation’s bankruptcy. |

| 7 | Cohen et al. [24] offer survey-based data detailing the extent of these activities. Klein [25], and Klein and Yang [26] cite more empirical studies that document how patent holders invest substantial resources to protect the economic value of their intellectual property from challengers. |

| 8 | In contrast, Dinopoulos and Syropoulos [23] assume that the production of RPAs uses only high-skilled labor, whereas the production of R&D services and manufacturing of final products uses only low-skilled labor. |

| 9 | Salient contributions to the general literature on contests include: Skaperdas [27] who axiomatized contest success functions; Clark and Riis [28] who examined rent-seeking contests with multiple winners and showed that rent is fully dissipated as the number of players grows large; Gradstein and Konrad [29] who focused on contests with multiple rounds when random factors are important; and, Baye and Hoppe [30] who analyzed the conditions under which rent-seeking contests are strategically equivalent to innovation tournaments. Influential works on elimination contests include: Rosen [31] who demonstrated that an elimination contest requires an extra prize for the overall winner to maintain performance incentives throughout the game; Brown and Minor [32] who argued that elimination tournaments often are designed to identify high-ability candidates in environments where innate talent cannot be readily observed; Stracke et al. [33] who investigated the incentives provided by single prizes versus multiple prizes; Cohen et al. [34] who examined the incentives provided by head starts awarded to the winners of early rounds; and Fu and Wu [35] who explored the optimal disclosure scheme in elimination contests to show that transparency yields a higher expected winner’s total effort while opacity leads to greater total effort. |

| 10 | The dynamic structure of our model also differentiates it significantly from the contributions of Dinopoulos and Syropoulos [36] who model the international diffusion of expertise as an outcome of appropriative imitation and costly self protection, and from Camacho et al. [37] who investigate how insecurity in the outlays of knowledge conditions the incentives of technology leaders to share their knowhow and of laggards to accept it. |

| 11 | This insight is rooted in the celebrated Stopler-Samuelson [38] theorem which provides a formal link between commodity prices as real rewards (wages) to factor owners (workers). |

| 12 | The integrated equilibrium is defined as the steady-state equilibrium that would emerge if, in addition to free trade in goods, all factors of production were perfectly mobile internationally. In other words, the integrated-world equilibrium treats the global economy as a closed economy in which, as standardly assumed, all goods and resources are intersectorally mobile. |

| 13 | The FPE set is defined as the set of possible allocations of factor endowments between the two countries that ensure factor prices (wages) do not differ internationally, goods are produced under the skill intensities that emerge in the integrated-world equilibrium, and every factor of production is fully employed in each country. |

| 14 | Importantly, using the terminology of Parente and Prescott [46], one could think of rent-protection activities as a barrier to innovation and growth that serves the purpose of removing the scale-effects property while preserving the endogenous nature of long-run Schumpeterian growth. |

| 15 | In general, parameter may differ across countries and may depend on the resources devoted to enforcing the protection of intellectual property. Ginarte and Park [48] provide more information and evidence on cross-country differences in the strength of patent protection for a sample of 110 countries. However, to keep the analysis simple and direct, in this paper we assume that this parameter is identical across countries. |

| 16 | See Varian [49] for more details on the properties of unit-cost functions. |

| 17 | A proper modeling of skill formation requires an endogenous division of population between high-skilled and low-skilled labor that results in a higher wage rate for high-skilled workers as compared to the wage rate for low-skilled workers, as shown in Dinopoulos and Segerstrom [39]. To maintain our focus on the interaction between skill abundance and skill intensities, we abstract from issues associated with endogenous skill formation. |

| 18 | We assume that, if two products command the same quality-adjusted price, consumers buy the higher quality product, although they are formally indifferent between the two products. |

| 19 | The Economist (10-22-2005) reported that IBM, a top patent holder, pledged 500 out of its 3,248 software patents at the time to the open-source community and placed them in a patent “commons”. In addition, Friedman [50] documents the fascinating case of “Apache”, a web server that was developed by an open-source self-organized scientific community in the absence of any patent protection. |

| 20 | For example, constant per-capita consumption expenditure () implies that , as indicated by (11). Moreover, the per-capita levels of RPAs , of R&D services , and of manufacturing output are also constant over time and identical across industries. Equation (15) implies that the long-run price of final consumption good p is also time invariant. Equation (3) implies that the per-capita level of RPAs satisfies , which is also constant over time and equal across industries. As a result, Equation (15) implies that per-capita value of innovation is also time invariant and thus the long-run value of grows at the constant rate of population growth ; that is, . |

| 21 | See Grossman and Helpman ([4]) for further details. |

| 22 | For instance, in quality-ladders growth models where innovation either improves the quality of intermediate inputs or results in total factor productivity improvements, captures the level of final per-capita output. See Grossman and Helpman [9] for additional details. |

| 23 | Inequality can be expressed in terms of skill intensities for . The definition of implies and yields . Thus, |

| 24 | O’Rourke and Williamson [51] document the factor-price reversal in Great Britain, which occurred in period 1840-1936. During that period the country went from a relatively closed-economy status to an open-economy status following the liberalization of the grain trade and the acceleration of technological progress stemming from the industrial revolution. Globalization and technological progress were equally important in generating this long-run change in factor prices. |

| 25 | Because there is a continuum of structurally identical industries of measure one, the output of each activity aggregated over all industries equals its indusry-level output. For example, the aggregate per-capita output of RPAs is equal to |

| 26 | One can easily check how the results of the analysis would change if one modified the ranking of skill intensities displayed in Assumption 1. |

| 27 | This assumption is supported by the empirical studies of Katz and Murphy [52], Huang and Whalley [53], Ciccone and Peri [54], and Autor et al. [55], which conclude that the value of the elasticity of substitution between low-skilled and high-skilled labor is significantly higher than unity (about 1.50). |

| 28 | If the skill intensity of RPAs is lower than that of R&D, then a sufficient condition for a downward-sloping relative demand for high-skilled labor is that the elasticity of factor substitution in manufacturing of final goods must be sufficiently greater than one and that the elasticities of factor substitution in the other two activities must be equal or greater than unity. |

| 29 | Ventura [41] has used the concept of an integrated-world equilibrium to analyze the effects of trade on growth in the context of the Ramsey (as opposed to an R&D-based) growth model. While feasibility and complexity considerations confine our analysis to a comparison of steady-steady equilibria, Ventura also analyzes the transitional dynamics associated with a move from autarky to free trade. |

| 30 | The distribution of per-capita factor endowments between Home and Foreign in the integrated-world equilibrium is illustrated by point in Figure A1 of Appendix B. |

| 31 | However, if the skill intensity of R&D exceeds the skill intensity of PRAs, then globalization causes Home’s long-run growth to fall and Foreign’s long-run growth to rise. Of course, one could readily introduce factor intensity reversals and obtain the same changes in the growth rate of both countries as they move from autarky to the integrated-world equilibrium. |

| 32 | For instance, Lewer and Van den Berg [6], who have surveyed an extensive set of empirical studies that include more than 190 cross-section and more than 400 time series regressions, report that about 9 percent of the cross sectional regressions and 18 percent of the time series regressions find a non-positive correlation between trade and GNP growth. In addition, Warciarg and Welch [60](Appendix 4) list 13 countries that have experienced negative or zero post-liberalization growth changes. Ben-David [61] documents the effect of economic integration on per-capita income for the original European Union (EU) members during the formation of the EU. Finally, Irwin [7] argues that the extensive trade reforms of the late 1980s and early 1990s increased average economic growth by about 1.0–1.5 percentage points but the growth effect was heterogeneous across developing countries. |

| 33 | The reasons for this property can be attributed to the assumptions that (i) all industries are symmetric, and (ii) the various activities within each industry are connected to each other dynamically. One could add another degree of freedom by assuming the existence of an outside-good produced under perfect competition, as in Dinopoulos et al. [5] and Grossman and Helpman [4], or by introducing differences in skill intensities in the production of final goods. This extension of the model is straightforward. |

| 34 | Furthermore, if the skill intensity of R&D is higher than the corresponding intensity of RPAs the model generates outsourcing of RPAs (as opposed to R&D services) for endowment-distribution points located in the interior of triangle OAB. |

References