Abstract

This paper aims to analyze the impacts of a backup agreement contract on the performance of a small agricultural producers’ citrus supply chain. A backup agreement contract, which ensures for each echelon that a quantity of products will be bought independently of real demand, is proposed to coordinate a three-echelon supply chain, aimed at improving income. After presenting an overview of the literature that shows various coordination mechanisms but no backup agreement proposals for supply chain coordination, this paper develops a decentralized three-echelon supply chain facing stochastic customer demand and includes the backup agreement as a coordination mechanism to guarantee a balanced relationship between the chain members. The model is tested in a real case study in Colombia, and a sensitivity analysis is provided. Results show that a backup agreement contract coordinates the small agricultural producers’ supply chain and improves income for each echelon, especially for the small producer. However, the economic mechanism complexity can limit coordination among echelons, mainly because of a lack of trust and consolidated supply capacity from small farmers. The foregoing requires the development of an associative structure by small producers, which is proposed as future research work.

1. Introduction

The supply chain, according to [1], is an integrated system that allows coordinating flows and processes from the raw materials to the final acquisition of a product by a customer. That system includes a wide number of stakeholders, like manufacturers, suppliers, carriers, warehouses, retailers, and even customers. In consequence to improve the performance and the business processes of a supply chain, coordination through integration, in an efficient, effective [2] and sustainable [3] manner, is essential. Supply chain management, according to [4], allows coordination between the parts of a supply chain, called echelons, to achieve efficient flows of products, services, information and decisions that provide value to the customer and improvements in the organization performance. As stated by [5] a supply chain in which echelons make decisions in isolation does not allow reaching adequate performance levels and is said to be an uncoordinated decentralized chain. On the other hand, if decision-making is done jointly, it is said to be a coordinated decentralized supply chain, which allows better performance, translated into revenue. Coordination requires an effort between the parties to work toward shared objectives [6]. Coordination and collaboration importance is supported by the improvement of internal and external processes, as well as the competitiveness, performance and organizational success in the echelons [7]. Coordination mechanisms as a strategy to achieve better performance have been deployed in different types of supply chains. Ref. [8] presents a coordination mechanism implementation in a humanitarian logistics chain, achieving cost reductions, increased capacity and improvements in care level. On the other hand, there are barriers to achieving coordination. Ref. [9] shows 10 case studies to establish how barriers between partners in a supply chain, affect performance and innovation and development processes. In the case of small farmers in agricultural supply chains, the lack of coordination mechanisms to achieve some integration level is translated into lower incomes mainly for those small agricultural producers, so the initial echelon [10].

However, integration in a decentralized supply chain is considered a complex problem, in view of independent decision-making in the network. Indeed, integration affects the flows between the links in the supply chain, and consequently income for each echelon of the supply chain. In a small agricultural producer’s supply chain, the initial echelon (i.e., that of agricultural produces) is the most affected in terms of income. In a decentralized supply chain, independent actors make decisions at different stages of the chain [11]. These conditions are not favorable to the small farmer in income distribution terms taking into account, their limited access to commercial networks, even affecting their economic sustainability. According to the International Council of Food Security of FAO [12] (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome, Italy), small producers are the main suppliers of long and complex supply chains, however, they always depend on third actors (intermediary, retailer) that buy them their products. In Colombia, small farmers located in the rural area must face, according to the National Planning Department (https://www.dnp.gov.co, accessed on 22 March 2022), limitations related to low access to productive assets (land, water resources, financing) in amounts necessary to generate efficient production systems. Moreover, the low capacities developed to manage those assets are restrictive elements for small agricultural producers’ economic development.

The citrus sector is of high importance in this country. Since 2012, fruit production in Valle del Cauca Colombia, represents one of the great business opportunities in the agricultural sector, with a 10% share of the total national production (535, 989 MT), according to the Commerce Chamber report 2014. In 2013, Valle del Cauca generated exports valued at USD 1.1 million, registering a growth of 28.2%, and sales were represented by citrus fruits.

Within the development strategies of the Valle del Cauca fruit plan, it seeks to strengthen links in production chains to capitalize on growth, promote articulations between different chains and reduce the effects of producers’ disintegration, through cooperatives or associations. In this sense, the authors of [13] emphasize cooperation importance rather than confrontation in the agri-food supply chain, especially in perishable foods. Consequently [14] states that a successful value chain must have mechanisms for cooperation and restoration of the parties’ joint interdependence. Guaranteeing the product supply and high quality implies committing from the producer echelon to the retailer. The above facilitates communication, increases the transfer information capacity to develop strategic plans in the face of variable demands, reduces logistics and transaction costs, guarantees less waste, and eliminates bottlenecks. Even the coordination mechanisms implementation allows establishing agreements with stable marketing parameters, achieving greater equity in terms of the benefits generated in the supply chain globally and individually for each echelon. Integration strategies have shown benefits in different problems related to agricultural supply chains. Ref. [15] addresses an inventory routing problem (IRP) for fresh products supply chains, showing that horizontal collaboration between suppliers contributes to reducing the total cost and emissions in the logistics system. The author points out that the small provider achieves better profits through collaboration. IRP deals with the simultaneous routing and inventories study, whose proper management has a major impact on the supply chain’s global performance. It currently considers objectives such as the minimization of food waste, energy use and emissions [16]. According to [17], inventory control systems with integration between echelons allow for maximizing the total value generated in the supply chain. Integration must be supported by information exchange in real time to achieve synchronization between demand and inventory level, which improves efficiency and reduces logistics costs. Ref. [18] show how vertical and horizontal integration improve effectiveness in an agricultural supply chain. In the first, harvesting, storage and distribution activities in an agricultural activity in a company are integrated and, in the second, the horizontal collaboration between heterogeneous agricultural companies for products distribution is evaluated. Integration is an issue that has been discussed for several years when [19] addressed the problem of efficiency based on the relationships established between the echelons in the chain. Since then, the competitive environment required making agreements between echelons to successfully meet the new market conditions. Based on the foregoing, these authors defined four states of evolution toward integration in the chain as: open negotiation, cooperation, coordination and collaboration.

According to [9], collaboration is a strategy that requires joint planning to achieve shared goals, involving cooperation between autonomous members of the supply chain. Collaboration has to do with the mutually beneficial relationships that are formed between echelons to share better results and benefits. These relationships are based on appropriate levels of trust [20], information exchange [21,22], joint decisions at strategic, tactical and operational planning levels [23,24] and resource sharing levers and limitations [24], which have a direct impact on the robustness of supply chain integration processes. However, authors such as [21,22,25,26] have studied the fact that the great integration challenge is to overcome the lack of trust, dependency and power relations between consecutive echelons. These elements become inhibitors of collaboration. On the other hand, [27] applied a maturity analysis model to implement a coordination mechanism in a small agricultural producer’s supply chain in Colombia. A great implementation opportunity of integration mechanisms is identified, considering the potential benefits offered to the small producer in improving their income.

Rural activity in Colombia, according to the National Development Plan 2018–2022 (https://www.dnp.gov.co/DNPN/Paginas/Plan-Nacional-de-Desarrollo.aspx, accessed on 22 March 2022), contributes 6.9% of added value and generated 16.7% of jobs in the country in 2017. However, the conditions in the countryside continue to be limited, due to the persistent poverty conditions, the low level of infrastructure, the limited ability to access marketing chains and the low levels of adding value to products, among others. In Colombia, DANE (2018) reports for 2017, multidimensional poverty in the populated and dispersed rural sector reached 36.6% and monetary poverty reached 36%

According to the small agricultural supply chain mentioned above, it can be pointed out that it is a decentralized chain. Supply chains from the decision-making approach can be classified as centralized; “when there is a single decision maker in the SC” [11] or decentralized “when several independent actors make decisions in the different stages of the SC”.

Integration in supply chains has been defined [19] as an evolutionary state, which starts with open negotiation and finishes in collaboration between members in the supply chain. That collaboration is the best state of integration, where strategic agreements between the partners are required, understanding that they belong to different organizations. Usually, centralization in decision-making is not possible but there are joint agreements that allow the best performance in the chain. However, when it comes to integration in decentralized chains, there are great cultural barriers and even, mistrust between the actors [28], which make this a difficult task. Authors such as those of [28] proposed coordination mechanisms as an alternative to solve these difficulties. The main mechanisms are [29]: information sharing through electronic data interchange (EDI), collaborative supply chain management techniques such as VMI (Inventory Management by the supplier) or CPFR (Collaborative Planning, Forecasting and Replenishment, as well as bilateral or multiparty collaboration formalized by supply contracts, which is this work focused.

In this sense, the authors of [5] relate some supply contracts such as: Price-only Contracts, Quantity Discount Contracts, Revenue-sharing Contracts, Franchise Contracts, Sales Rebate Contracts and Backup Agreement, which allow the coordination of the chain, improving its economic performance. The Backup Agreement is addressed in this work, which according to [11] are agreements established between supplier and buyer, to regulate the good or service purchases. It allows maintaining the fixed price, even if there are changes in the market. Backup contracts allow the seller to maintain a support inventory after the first delivery is done. A buyer can make the decision to buy all the remaining units maintaining the initial contract conditions when observing demand behavior. In case the buy option is not used, the buyer will pay a penalty for not buying the agreed backup inventory. The backup agreement is intended to help the supplier to reduce the demand uncertainty impact on their income.

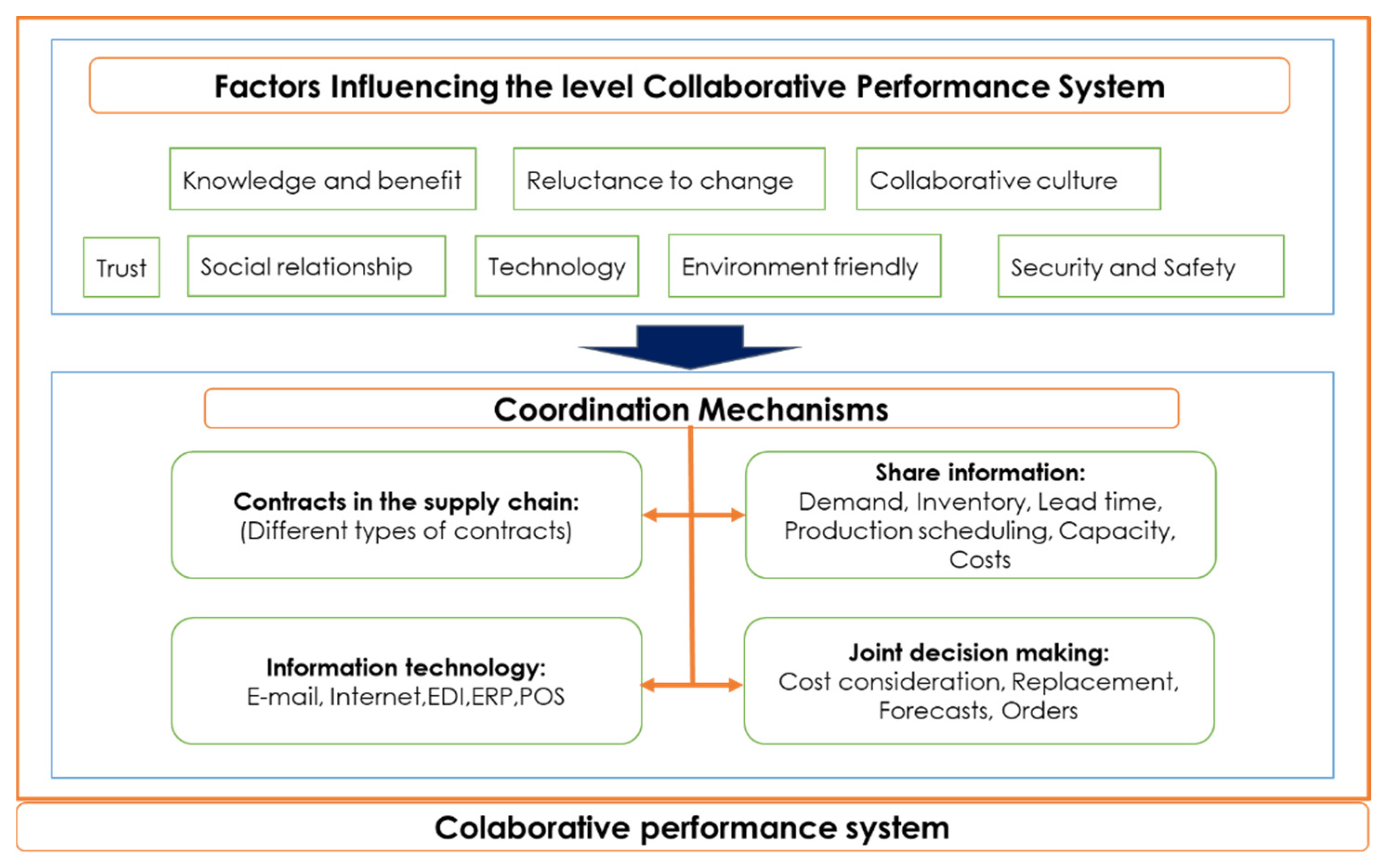

Authors such as those of [19] assure that the supply chain integration guarantees greater benefits in cost reduction and better performance. Additionally, they define collaboration as the best strategy for integration in supply chains, where there is no centralization in decision-making. Through empirical evidence, Ref. [30] establishes that the higher levels of integration, the greater the competitive capabilities and business results. On the other hand, supply chain integration is related to coordination mechanisms, aligning and interconnecting business processes both inside and outside the company [31]. Furthermore, supply chain collaboration benefits are discussed in [32] identifying success cases in diverse supply chains ranging from the automotive industry to the meat industry. Defines agility and collaboration in supply chains as two strategic tools that support competitiveness in the face of globalized market conditions, increased competition and evident volatility. Also, information exchange, as well as the use of technologies, is decisive in the integration process’s success. However, the collaboration performance in fresh produce supply chains can be affected by factors such as lack of knowledge of the benefits of collaborative work systems, little desire for change, absence of a collaborative culture, lack of trust, technology and information, social relationships, respect for the environment, sustainability, security and protection. Thus, performance systems of collaborative processes are influenced by various factors that are decisive in achieving collaborative scenarios [32]. Coordination mechanisms are used to motivate the decentralized chain members to get better performances in the supply chain [33]. In the literature, four coordination mechanisms are identified, according to [28,34], such as Contracts, to Share Information, Joint decision making and Information technology. According above discussion, coordination mechanisms can be affected by barriers that influence the performance of collaborative systems. In this sense, an approach for understanding the relationship between coordination mechanisms presented in [28,34] and the barriers that influence the performance of collaborative systems as mentioned [32] is presented in Figure 1. Complementarity proposed by the two approaches is identified and even more in relation to a collaborative performance system. It is possible to state that coordination mechanisms will be influenced by each aspect presented in [32] and will determine the collaborative performance system level.

Figure 1.

Framework for classifying coordination mechanisms and collaborative performance system, adapted from [28,32,34].

This work focuses particularly on the contract coordination mechanism and, studies the backup agreement as an integration mechanism in a small agricultural supply chain in a developing country. More precisely, the present paper aims to present a backup contract as a coordination mechanism in small agricultural producers’ supply chains, which are by nature decentralized. More precisely, a backup contract is formulated in a decentralized supply chain of small agricultural producers located in the center of Valle del Cauca, Colombia, in an interactive problem-solving approach. The coordination mechanism proposed allows the improvement of the chain performance and income level of the small producers. The mathematical model that underlies the backup contract is presented, the income behavior is studied and particularly the income of the producer. It is concluded that this type of contract allows the improvement of the performance and incomes in the supply chain.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the justification and presentation of the interactive problem-solving approach and the case used to develop it are presented. Section 3 shows the main descriptive results of the case study and the developments made to define the main needs and decision issues to build the model. Section 4 presents the proposed model to analyze the impacts of a backup agreement contract on a decentralized supply chain with three echelons and stochastic demands, as well as the results of the model application on the proposed case and its sensitivity analysis. Finally, Section 5 and Section 6 present the generalization and implication issues, and the main conclusions of this work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study, Justification, Presentation and Data

To identify, characterize and account for the coordination mechanisms and backup agreement issues in Colombian small producers’ citrus supply chains, we propose a mixed case study approach. A mixed-method case study combines a qualitative case study approach with a quantitative data production procedure (either company-based data collection, questionnaire-based data collection or OR-based data production via optimization) in order to both qualify and quantify a complex phenomenon. Thus, an OR-based mixed-method case study approach allows to both study complex phenomena within their contexts (as in qualitative case studies [35]) and provide at the same time, data issued from optimization (as in operations-research case studies [36]) but with a strong contextual-based, reality representation viewpoint [37]. Therefore, before the presentation of the case study, it is important to present the main assumptions and choices made to select it [38]:

- Aim of the case study: The aim of the case study is to identify the characteristic aspects of small producers’ supply chain in a developing country, in order to evaluate their performance when using a backup agreement as a coordination mechanism. In addition, the aim is to evaluate the coordination mechanism impact on the better income distribution throughout the chain and, in particular, on the small agricultural producer is an additional purpose.

- Nature, methodological path and type of case study: Taken into account the aim and, the literature review section, the case study proposed here will be an abductive one, based on the notion of the “modeling and optimization cycle of Ackoff” (explained in [39]). Indeed, the methodological path of the case study starts with a qualitative characterization of the field, the analysis of the observed reality, to then define a first optimization problem, solve it and propose the first solution. Then, with the field stakeholders, the solution is validated or improved, as well as the decision problem, if needed, to ensure that the representation of the observed reality fits the stakeholders’ needs and visions. Once all the field, decision problem, optimization model and solution are considered satisfactory, the problem can be considered solved.

- Number and selection criteria of the case study/studies: The case study is one of the most appropriate methods to learn about a real situation, where complex causal relationships explanation, detailed descriptions, generating theories or accepting exploratory theoretical positions, analyzing changes processes and studying a phenomenon that is ambiguous, complex and uncertain is required (Ref. [39]). In this research, three criteria are defined to use the case study methodology, they are: The contracts theory has not been widely applied in small agricultural producers’ supply chain even less in developing countries [10], which offers opportunities to deepen in a field where research and applied theory are in their preliminary phases. As the second criteria, because it is a practical problem where the small producer experiences are important to survey agricultural practices information and the related data. Finally, as the third criteria, the context related to small farmers, a developing country and the low income levels, are special interest topics in this research work.

- Data collection methods: This research is a deductive case study, where the existing theory on contracts as coordination mechanisms in decentralized supply chains is used to investigate a phenomenon focused on small agricultural producer chains. During the study case development, it is intended to test the existing theory to be confirmed or rejected. A supply chain of small citrus producers located in the center of Valle del Cauca in Colombia, South America, is taken as a case. Both secondary and primary sources are used to obtain information. The first allows establishing the number of small producers in the geographic area. In this case, the Rural Direct Technical Assistance Users Registration (RUAT) is consulted. In Colombia, it is an instrument in which small and medium-sized producers who access the rural direct technical assistance service offered by the government are registered. As a result, a total of 283 small and medium-sized citrus producers were identified, located in eight (8) villages in the rural area in a municipality in Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Subsequently, primary sources consultation is used with a survey. The survey was applied to 99 producers, equivalent to 34.98% of the total population. Due to the fact that there is a known population of small agricultural producers, simple random sampling is used as a strategy, which allows calculating a representative sample and reduces 40 biases. The sample representativeness is validated using a confidence level of 90% and an error margin of 7% as estimation parameters. A representative sample of 93 farmers is obtained, which allows inferring that a sample of 99 farmers consulted is suitable for study.

- The interview was used to apply the survey with 67 questions that inquire about: A. Strategic aspects: Crop location decisions, fruit to be grown and planting season. Additionally, on input and resource budgets and environmental management plans. B. Tactical aspects: Preparation for planting, harvest programming, negotiation models, product traceability control, transportation and sales planning B. Operational aspects: Harvesting processes, personnel hiring, pricing, inventory policy, among the most important aspects. Finally, based on this information, the data required for the backup contract model formulation is obtained.

- 5.

- Epistemological issues: The case study is based on the Social System Thinking vision of [40], for which a problem needs to be approached beyond disciplines, in a systemic, purposeful viewpoint (i.e., identifying the system’s purpose as well as each of its indivisible parts, its individual purposes, and the interactions between those parts that make the system work as a whole). That is extremely connected to the methodological path presented in the next subsection.

2.2. The Problem Solving Framework

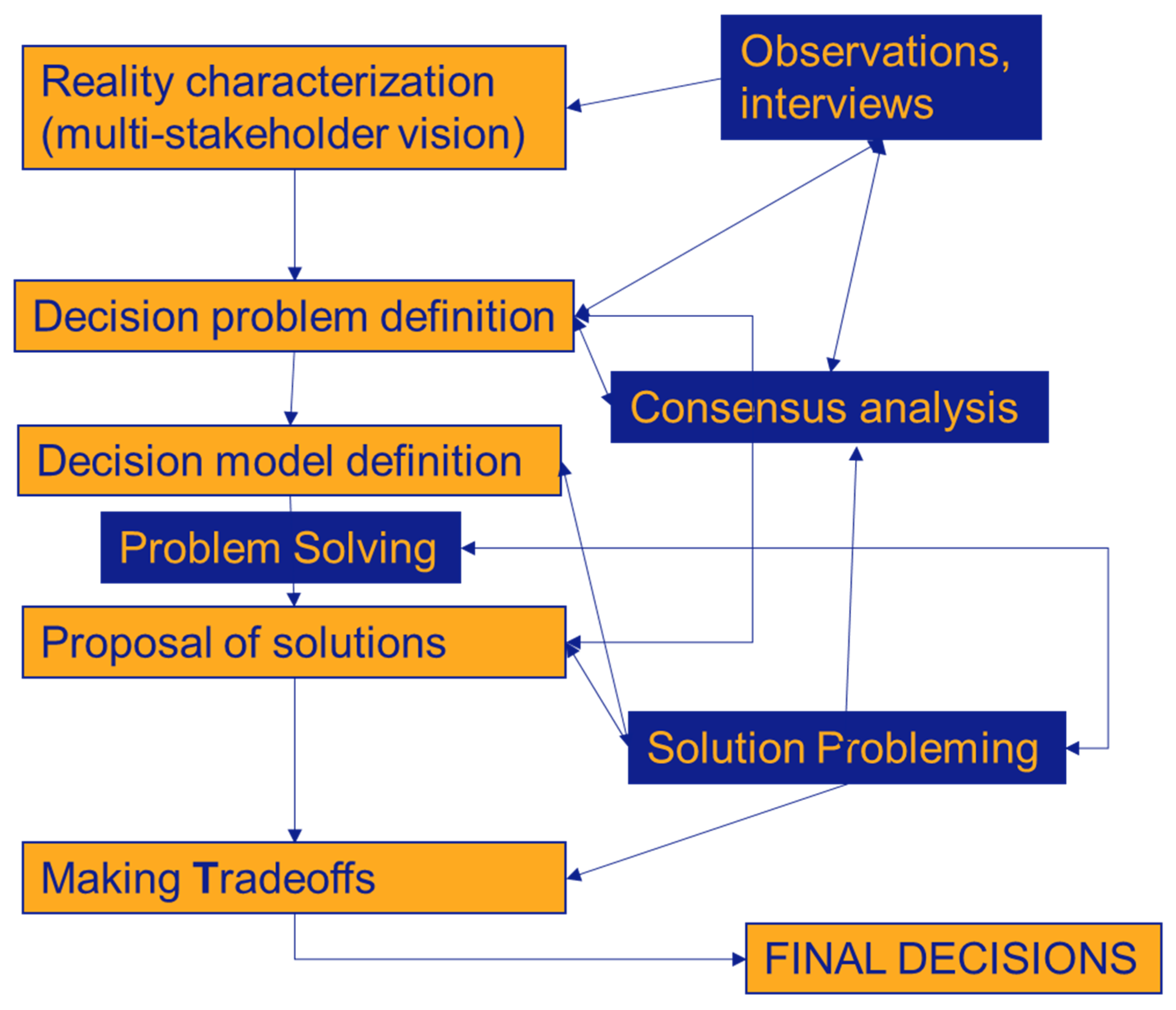

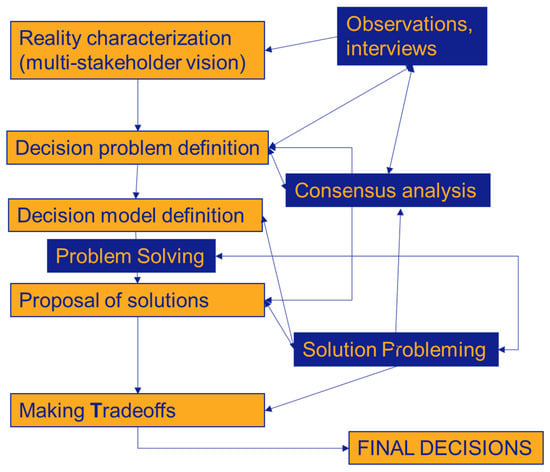

Coordination in decentralized chains has been shown to improve their performance. In this sense, two analysis scenarios are presented: the supply chain performance without the backup contract as the first scenario, and the behavior applying the contract as a coordination mechanism. This analysis is done in income terms throughout the chain. The case study includes three echelons (small producer, intermediary and retailer) in the supply chain. To make this analysis, an iterative procedure of problem-solving (illustrated in Figure 2) is proposed:

Figure 2.

The problem-solving cycle adapted to the mixed-method case study, elaborate by authors from considerations in [36,41].

In an interactive and iterative problem, the fundamental purpose is to obtain a solution that suits the decision maker, who is, in the current case, a group of stakeholders instead of a unique individual. The procedure of problem solving needs first to identify the situation to address and the decision problem to solve, for this data collection and observation procedures are needed (as explained in Section 2.1. while presenting the case study methodology). Then, once the decision variables and problem are defined, a first model can be made, and a solution is found (problem-solving phase). After that, the suitability of this solution, then of the model, and finally of the represented decision problem need to be assessed (solution problem). To do that, both sensitivity analysis and exchange with stakeholders are included.

If either the solution, model or decision problem is considered not to suit the represented reality, then can be modified (the one that is considered as not suitable) and re-validated until all three are considered satisfactory for all stakeholders. In the following, we present the case study with the sensitivity analysis and the model considered the most suitable to solve the decision problem addressed in this research.

3. Implementation and Results of Analysis

3.1. Casestudy General Information

As previously mentioned, a small citrus supply chain producer is taken as a case study. This supply chain has 99 producers, 7 intermediaries and 5 retailers consulted. It is a supply chain with three echelons: producers, intermediaries and retailers. One of the biggest costs for the producer is labor and raw material or supplies used in the crop. Weekly product sales are 377 kg/week on average, and its sale price has an average value of $1523. Price is mostly conditioned by the intermediaries. Otherwise, the producer can decide the sale price based on criteria such as demand, input prices and sales projections. Not all small producers bear storage or inventory management costs. They estimate a savings cost of $228/kg.

On the other hand, intermediary presents an average weekly sale between 209 kg and 330 kg. Purchasing price from the producer is determined through direct negotiation. This value is $953.55/kg on average. Profit percentages in the intermediary echelon are between 30% and 50%. The biggest cost for the intermediary is the fruit purchased cost from the small producer.

Finally, the retailer presents a weekly demand of between 1000–1500 kilos, the total marketing cost is $179.65/kilo.

The backup agreement has an economic penalty (b) to the intermediary, for units not taken within the agreement. Under operating criteria such as costs, percentage of product loss in the producer, it is established as penalty cost within the contract as follows:

b = Producer Cost *(% of untaken units).

According to the supply chain characterization, the sale price, demand in each echelon and commercial activity costs will be used as relevant factors.

It is intended to improve the flow of resources, information and money by applying a backup contract model, which as a coordination mechanism allows harmonizing of the relationships between echelons in the chain. To verify the contract’s success, the profits optimization is translated to income terms for each supply chain member.

To carry out the mathematical model programming, the optimization software IBM ILOG CPLEX was used, through the Optimization Studio, which allows for generating a prescriptive analytical solution of the model.

3.2. Proposed Model Application and Results Discussion

Data were obtained from a set of surveys carried out to small farmers, intermediaries and retailers as aforementioned, in a citrus supply chain. The structure of the surveys and the characterization method and results are presented in [27]. In this work, we do not focus on stakeholders’ and process characterization but on cost and revenue structure and their variation considering two scenarios. The first is a non-coordinated decentralized supply chain scenario, which represents the situation before the deployment of the backup agreement as coordination mechanism. As a second scenario, a coordinated decentralized supply chain using a backup agreement as a coordination mechanism is shown.

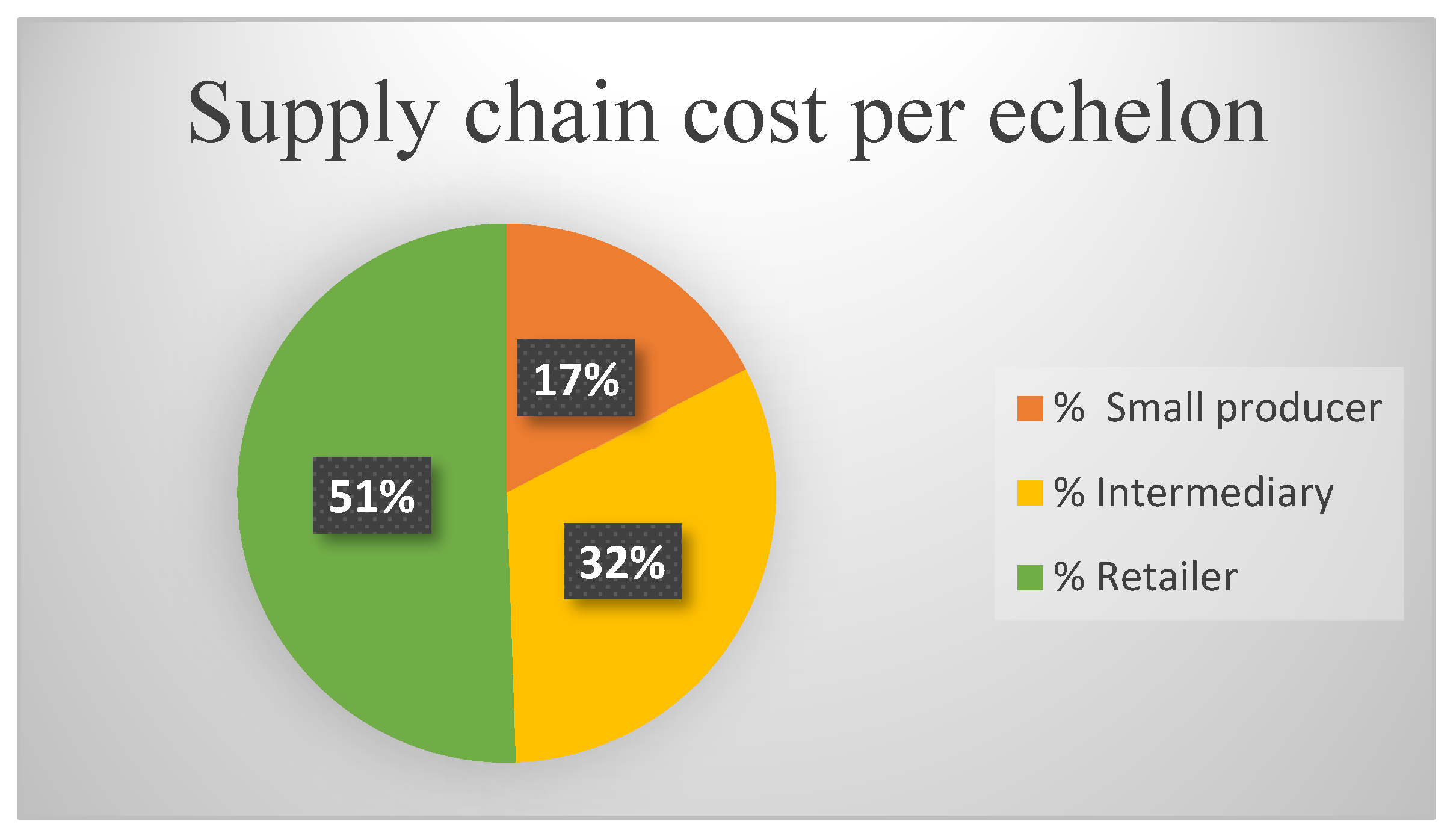

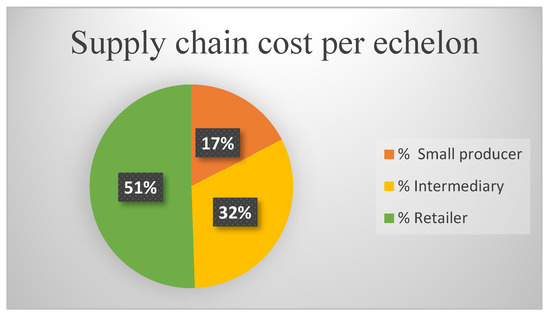

Before analyzing the scenarios, it is important to present the main results of the cost (Figure 3) and revenue structure (Table 1 for scenario 1 and Figure 4 for scenario 2). Figure 3 shows that costs to the retailer represent 50.7% and in the producer 17% of the total cost in the supply chain. This difference is mainly due to weak registration and control methods implemented in the producer echelon. However, retailers keep a precise and organized cost control system.

Figure 3.

Cost per echelon as a Supply chain total costs percentage. (Source: Authors).

Table 1.

Chain profit results without backup agreement.

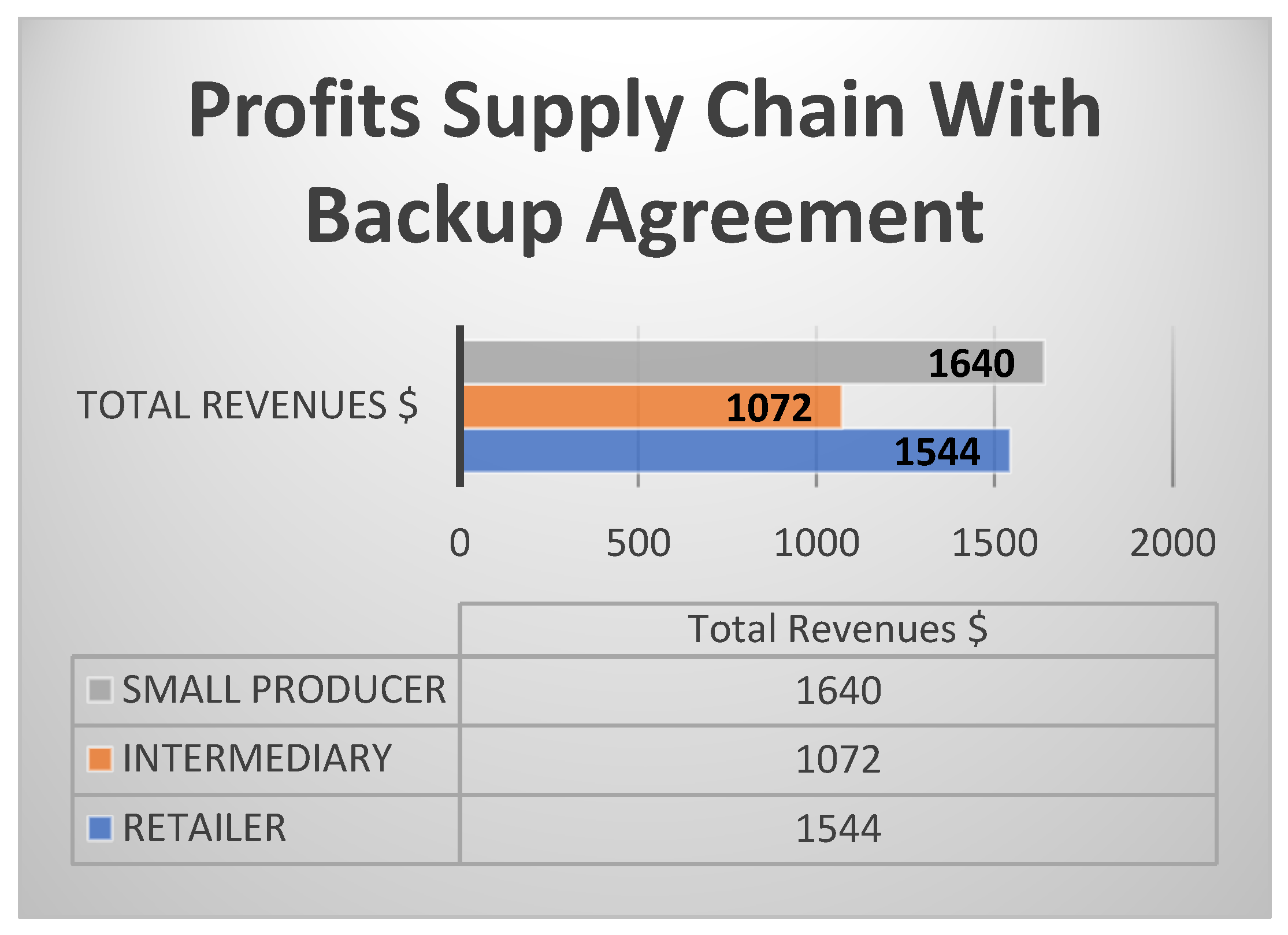

Figure 4.

Supply Chain profits with backup agreement. (Source: Authors).

According to the results (See Table 1), profits increase in the downstream supply chain. The less profit generated in the small producer echelon can be evidenced. The absence of supply chain integration is a potential cause, where the small producer is subject to the intermediary and retailer conditions in price and order quantity terms among others.

On the other hand, the results for the second scenario, that is, with a backup agreement show a more balanced profit-sharing, in which producers reach the highest revenues of the chain (Figure 4). Indeed, in the first scenario, producers have less than half of the revenue of intermediaries and less than 1/3 of that of the retailers. In the second scenario, producers have 1.5 the revenue of intermediaries and nearly the same revenue of retailers, although a little higher.

Once the backup agreement is implemented, profits increase is observed and, flows are regulated along the supply chain. A decrease in the intermediary profits share in the supply chain is observed, due to the economic penalties policy for not taking units included in the backup agreement.

The integration mechanism requires a sharing of both the product loss risk and greater profit by each echelon in the supply chain. A comparison of profits generated in the supply chain, with and without a backup agreement, is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Profits with and without backup agreement. (Source: Authors).

As is shown in Table 2, an increase of 53.10% in the supply chain total profits is achieved once the backup agreement is applied. This is achieved because contract policies regulate purchases in concordance with demand. On the other hand, the decentralized supply chain coordinated with the backup agreement shows a profits increase for each echelon. The foregoing allows motivating the chain members to use the contract. Finally, the small producer is who receives the greatest economic benefit after the backup agreement is applied. This is largely due to the better supply management within the chain. Speculation is controlled and the risks associated with the product not selling are shared.

However, it is necessary to address the economic mechanism that allows structuring relations in the supply chain studied within the framework of coordination mechanism implementation such as the backup agreement. According to [40], an economic mechanism refers to the combination of economic, organizational and administrative levers, and methods that regulate organizational structures to get efficient results. Based on the above, in this work, the economic mechanism is understood as the organizational structure that is required by the small producer to interact efficiently downstream in the supply chain and achieve an adequate coordination mechanism implementation. As mentioned in [42,43], small agricultural producers in Latin America have limited access to marketing networks that allow them to improve their income. Market disconnection and the sustenance needs generate unfavorable conditions in products price settings. Also, disarticulation of planting and harvesting practices and their limited associative capacity generates an imbalance in the income distribution in the agricultural supply chain. In this sense, Ref. [44] classifies small agricultural producers into three categories from the point of view of value generation capacity: Those of subsistence, those linked to small undeveloped value chains, and a third category which corresponds to a small proportion, linked to well-defined value chains. However, small farmers tend to prefer group actions to individual ones, mainly when risk- and cost-sharing allows them to increase their benefits [45]. Thus, authors such as [46,47,48] have raised the need to strengthen associative models among small producers, to achieve supply consolidation and improve negotiation conditions. Associative models such as cooperatives and associations are the economic mechanisms that, according to authors such as [49,50], allow the best performance of these relationships in the chain. Cooperatives according to [48], are non-profit organizations, which are created for the social benefit of a group of people. These organizations that belong to the solidarity sector of the economy, work by associating a number of people, taxpayers, managers and workers in the cooperative. On the other hand, Ref. [51] defines Associations as groups of people or institutions that work in a coordinated manner to obtain common benefits. In general, it can be argued that the economic mechanism for the implementation of a coordination mechanism such as the backup agreement requires the creation of an associative model that allows the organization of small producers [52]. In Latin American countries, the small producer is the echelon that frequently works informally and lacks an organizational structure. In any case, it is necessary to delve into this topic in order to identify the most appropriate economic mechanism in the context of a developing country, which is why it is proposed for future research.

4. Proposed Model and Sensitivity Analysis

The newsvendor problem is the underlying model in most contracts to coordinate supply chains [10]. It is a single-period inventory control model where the entity faces the problem of a newspaper seller who must determine the quantity to buy before the sale becomes effective, but who cannot replenish once the quantity to order Q has been selected. Each missing unit is penalized with an opportunity cost and each surplus unit can be sold at a salvage value. In addition, the demand is random.

The mathematical model presented below is a probabilistic model that is linked to the decision-making knowledge area. The framework developed in this instance is identified as a stochastic programming model where a non-trivial dimension mathematical optimization problem is addressed. The backup agreement model handles the demand as a random variable that is treated as the previously explained newsvendor problem. The profits maximization is proposed as an objective function in a non-coordinated decentralized scenario and a second scenario, where the objective function is also maximization and the contract is used as a coordination mechanism and a win-win relationship is assumed to motivate echelons participation.

This section presents the final model and the results obtained after problem-solving. In order to explore model sturdiness a sensitivity analysis in different scenarios is done, in which its performance is evaluated in regard to demand and producer costs variability, as it happens in a real context.

4.1. Proposed Modeling Framework

Two models are shown to represent the decentralized supply chain before and after the backup agreement as a coordination mechanism is applied. The main assumptions are derived from the case study results and presented below.

Decentralized scenario modeling without contract.

- -

- Assumptions

- ▪

- There are no prior price agreements/relationships of opponents between actors.

- ▪

- It is assumed that all the quantities’ flows through the supply chain are equal: Q1 = Q2 = Q3.

- ▪

- Intermediaries represent the dominant (or focal) echelon.

- ▪

- There are no inventory policies.

- ▪

- Profits generated by each echelon are related to their own activities’ costs.

- -

- Sets

According to factor behaviors, such as sale price and cost variation in each echelon in the supply chain, the following sets are established (Table 3):

where 1: small producer; 2: intermediary; 3: retailer.

a = {1,2,3}

Table 3.

Parameters Decentralized scenario modeling without a contract.

- -

- Parameters

- -

- Decision variables

- -

- Objective Function: Maximize supply chain profits.

- -

- Constraints

Constraint 1: Small Producer profit.

Constraint 2: Intermediary profit

Constraint 3: Retail profit, generated

Contract model application.

- -

- Assumptions

- ▪

- An inventory policy is established.

- ▪

- A penalty value (b) on the intermediary echelon profit is established.

- ▪

- Two purchasing time periods (ε1; ε2) are established.

- ▪

- Period demands are correlated.

- ▪

- The retailer is the dominant echelon.

- ▪

- No return policy is allowed, due to the nature of the supply chain

- -

- Win-win condition with backup agreement application in the supply chain

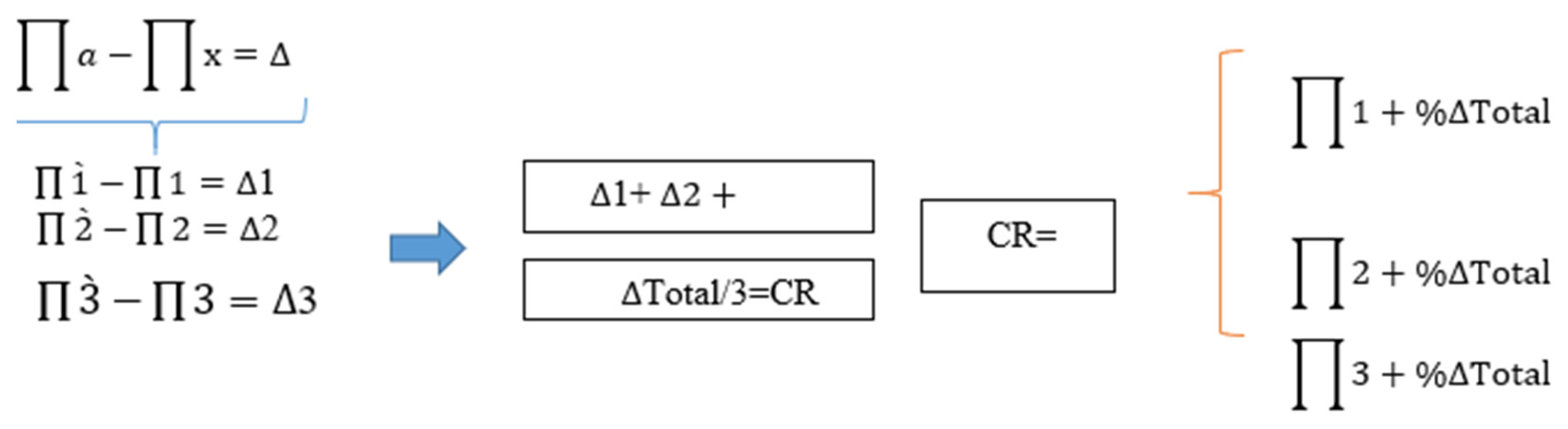

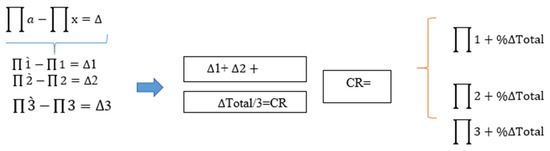

To motivate the supply chain members to use a backup contract, it must be guaranteed better income compared to that generated without a contract. This condition is formulated as follows:

Total profits ∆ are distributed among the 3 supply chain echelons (See Figure 5):

Figure 5.

Distribution of total profits.

- -

- Setswhere 1: Small producer; 2: Intermediary; 3: Retailer.x = {1,2,3}

- -

- Parameters

- The main parameters used in the model are defined in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Parameters Contract model application.

Table 4.

Parameters Contract model application.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| E(D): | Estimated demand |

| Cp: | Production costs |

| Cm: | Maintenance cost |

| Cy: | Producer preparation cost |

| Q: | Purchasing order quantity |

| r1: | Product price according to link i |

| Cp: | Product purchasing costs from the producer |

| Cpr: | Intermediary preparation cost |

| CA: | Cost of ordering intermediary |

| Cit: | Product purchasing costs from the intermediary |

| Cm2: | Inventory Carrying Cost |

| CA2: | Retail Order Cost |

| Crieg: | Risk cost |

| P: | Product percentage for the first delivery established in the backup agreement |

| (1-V): | Sales Percentage |

| w: | Percentage of units not taken within the contract |

| b: | Economic penalty per unit not taken within the contract |

| Ch: | Inventory maintenance cost of units not taken within the contract |

| Cph: | Penalty cost to the intermediary for not taking the units within the backup agreement (intermediary) |

| m: | Penalty cost in percentage for units not taken within the contract (Retailer) |

- -

- Decision variables

- -

- ObjectiveFunction: Profit maximization in the supply chain with a backup agreement

- -

- Constraints

The proposed model includes two purchasing time periods (ε1; ε2). Constraints are based on a three echelons supply chain once the backup agreement begins.

The backup agreement’s initial conditions are defined in the first period of time such as: units in backup, fixed price for the backup units, total production order and penalty cost for untaken units. Likewise, order costs for intermediary and retail are included in constraints. FF.

Constraint 1: Small Producer profit according to estimated demand E(D). Period 1.

Constraint 2: Intermediary profit according to estimated demand E(D). Period 1.

Constrain 3: Retailer profit according to estimated demand E(D). Period 1

In the second time period, once the intermediary and retailer know the demand behavior, they use the backup inventory agreed. Parameters as percentage taken and not from backup agreed inventory included in the contract and, the respective economic penalties to calculate profits in the supply chain.

Constraint 4: Small Producer profit according to estimated demand E(D). Period 2

Constrain 5: Intermediary profit according to estimated demand E(D). Period 2.

Constraint 6: Retailer profit according to estimated demand E(D). Period 2

Constraint 7: Total profits during two purchasing periods.

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Scenario #1—Demand Variation

The variation in demand is established with an increase of 50% and a decrease of 60%. The results generated are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Profit Behaviour with demand variation (Source: Authors).

Regarding an optimistic or pessimistic demand scenario, the backup agreement guarantees a profit increase for each supply chain member.

Additionally, despite a pessimistic demand scenario, the profits remain higher in the decentralized supply chain with coordination mechanisms regarding the supply chain without a contract.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Scenario #2—Costs Variation

In this scenario, the intermediary and producer costs are assumed as equal. The results generated are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Profit Behaviour with costs variation (Source: Authors).

Considering intermediary and producer costs to be equal, profits increase in the supply chain with the backup agreement, regarding the profits obtained in the chain without a contract. This is largely due to the supply chain’s total cost decrease. Even though the intermediary reaches a higher profit level in the chain, profits increase for all the supply chain members in comparison with a supply chain without a contract.

5. General Main Implications

In consideration of public policies in developing countries, this research serves as support to generate incentives that promote integration with the use of contracts that ensure sustainability and better performance in the small agricultural producers’ supply chain. In the food security field, the different coordination mechanisms can be leveraged with strategies for food supply as Food Hubs. An implication that is even restrictive has to do with tax and fiscal aspects that, although not included here, should be taken into account. In developing countries, fiscal tax burdens become a greater restriction considering the small producer’s level of poverty. A collaborative culture that motivates the emergence of organizational models should be developed. Supporting the horizontal, vertical or lateral integration would allow a successful economic mechanism. The purchases and sales relationship practices with a transactional emphasis are a great barrier. This requires small producers to organize themselves in associative models and managers downstream in the supply chain to migrate to a collaborative negotiation style.

6. Recommendations and Conclusions

The backup agreement as a coordination mechanism in a decentralized fruit supply chain allows the improvement of its performance and integration as well as income flow between chain members. Results presented by the underlying backup agreement mathematical model confirm the profits optimization, in income terms. There is an increase of 53.10% in the chain’s total profits. Small producers achieved greater participation in the chain’s overall profit, its profits increased by 239%. This increase is largely due to the contract policies, which promote a well-adjusted commercial relationship between buyer and seller allowing to maintain a second backup inventory. The buyer can make the decision to purchase the backup units according to demand. The backup agreement aims to coordinate the supply chain in an uncertain demand environment. In this sense, the backup agreement model involves the newsvendor problem as a strategy for estimating random demand. The newsvendor model tries to decide the quantities that should be purchased to maximize profits, taking into account the random demand and penalizing the surplus stock. Finally, it can be established that the backup agreement application in a decentralized chain reduces individualism and opens the producers to actively participate in the commercial decisions in the supply chain.

As a major limiting aspect in the research development, the small producers lack the willingness to attend to the information gathering. Although the sample is representative, from 283 small producers identified as a population, it was only possible to survey 99 due to various difficulties in locating them. It is important also, to refer to the data variability of production costs, production levels, sales prices reported by small producers. The lack of control in the production process and even difference in some cultural practices for planting and harvesting was evident. Finally, a limitation in the different echelons in the supply chain has to do with change resistance, which can be called a cultural limitation to changing the approach to doing business.

Based on the implications and limitations found, future research related to the risk approach in the implementation of different contracts in the small agricultural producers’ supply chain is planned. Additionally, a more detailed study is proposed on the chain maturity for contract models implementation, especially in intermediary and retailer echelons, which maintain a dominant negotiation relationship. On the other hand, it is considered pertinent to delve into the fiscal and tax implications of implementing these contracts. Finally, selecting an associative model for small producers, using a multicriteria decision model considering the developing countries’ context allows contributing to breaking down the mistrust barrier, consolidating supply and unifying operational and marketing practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L.P.O. and M.N.R.P.; methodology, D.L.P.O., M.N.R.P. and J.G.-F.; validation, D.L.P.O., M.N.R.P. and J.G.-F.; formal analysis, D.L.P.O., M.N.R.P.; investigation, D.L.P.O., M.N.R.P. and J.G.-F.; resources J.G.-F., D.L.P.O. and M.N.R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.R.P. and D.L.P.O.; writing—review and editing—D.L.P.O. and J.G.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data used for this research was obtained by the authors through instruments such as surveys, applied directly from small agricultural producers. The authors attest to the veracity of the data obtained.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chopra, S.; Meindl, P. Administración de la Cadena de Suministro; Pearson Educación: Mexico City, Mexico, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mentzer, J.T.; Flint, D.J.; Hult, G.T.M. Logistics service quality as a segment-customized process. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazlo, C. The Sustainable Company: How to Create Lasting Value through Social and Environmental Performance; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aldana-Bernal, J.C.; Bernal-Torres, C.A. Factores Blandos en la Gestión de Integración de las Cadenas y/o Redes de Abastecimiento: Aproximación a un Modelo Conceptual. Inform. Tecnol. 2018, 29, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pérez, E.D.; Martínez, J.M.V.; Torres, J.M.F. Los Contratos Como Mecanismo de Coordinación en Las Cadenas de Suministros. Revista Caribeña de Ciencias Sociales, 2015. Available online: http://www.eumed.net/rev/caribe/2015/09/contratos.html (accessed on 12 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Malone, T.W.; Crowston, K. El estudio interdisciplinario de la coordinación. Encuestas Comput. ACM 1994, 26, 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.R. Mecanismos de Coordinación en Supply Chain Management. Revista Negocios Globales, 2015. Available online: http://www.emb.cl/negociosglobales/articulo.mvc?xid=2289&tip=11&xit=mecanismos-de-coordinacion-en-supply-chain-management (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Osorio Ramírez, C. Mecanismos de Coordinación para la Optimización del Desempeño de la Cadena Logística Humanitaria Mediante Modelamiento Estocástico. Caso Colombiano. Ingeniería Industrial, 2016. Available online: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/60053 (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Soosay, C.A.; Hyland, P. A decade of supply chain collaboration and directions for future research. Supply Chain. Manag. 2015, 20, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña Orozco, D.L.; Agudelo, S.V.; Rivera, L. Análisis del comportamiento del contrato de distribución de ingresos en una cadena de abastecimiento frutícola. Rev. Int. Métodos Numéricos Para Cálculo y Diseño en Ing. 2019, 35, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoccaro, I.; Pontrandolfo, P. Supply chain coordination by revenue sharing contracts. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2004, 89, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSA. Vinculación de Los Pequeños Productores Con Los Mercados; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D.; Merton, I. Partnership in Produce: The J Sainsbury Approach to Managing the Fresh Produce Supply Chain. Supply Chain. Manag. 1996, 1, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, D.H. Cadenas de Valor como Estrategia: Las Cadenas de Valor en el Sector Agroalimentario. Estación Experimental Agropecuaria Anguil, Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria 2002. Available online: https://inta.gob.ar/sites/default/files/script-tmp-cadenasdevalor.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Soysal, M.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.M.; Haijema, R.; van der Vorst, J.G. Modeling a green inventory routing problem for perishable products with horizontal collaboration. Comput. Oper. Res. 2018, 89, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batero Manso, D.F.; Orjuela Castro, J.A. El problema de ruteo e inventarios en cadenas de suministro de perecederos: Revisión de literatura. Ingeniería 2018, 23, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, I.C.G.; Cano, L.A.F.; Peña, O.D.L.; Rivera, C.L.; Bravo, B.J.J. Design of an inventory management system in an agricultural supply chain considering the deterioration of the product: The case of small citrus producers in a developing country. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2018, 16, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallombardo, G.; Mirabelli, G.; Solina, V. An Integrated Model for the Harvest, Storage, and Distribution of Perishable Crops. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speakman, R.E.; Kamauff, J.W., Jr.; Myhr, N. Unainvestigación empírica sobrela gestión de la cadena de suministro: Una perspectiva sobre las asociaciones. Gest. Cadena Suminist. Una Rev. Intern. 1998, 3, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, X.; Tang, O.; Price, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, W. Supply chain collaboration for sustainability: A literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 194, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chuang, C.H.; Hsu, C.H. Information sharing and collaborative behaviours in enabling supply chain performance: A social exchange perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 148, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, B.; Yen, H.R.; Sheu, C. Information technology and supply chain collaboration: Moderating effects of existing relationships between partners. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2005, 52, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Feliu, J.; Morana, J. Collaborative transportation sharing: From theory to practice via a case study from France. In Technologies for Supporting Reasoning Communities and Collaborative Decision Making: Cooperative Approaches; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 252–271. [Google Scholar]

- Phonin, S.; Likasiri, C.; Dankrakul, S. Clusters with Minimum Transportation Cost to Centers: A Case Study in Corn Production Management. Games 2017, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Zheng, R.; Deng, H.; Zhou, Y. Green supply chain collaborative innovation, absorptive capacity and innovation performance: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, C.; Wagner, S.M.; Petersen, K.J.; Ellram, L.M. Understanding responses to supply chain disruptions: Insights from information processing and resource dependence perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 833–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, D.L.P.; Gonzalez-Feliu, J.; Rivera, L.; Ramirez, C.A.M. Integration maturity analysis for a small citrus producers’ supply chain in a developing country. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2021, 27, 836–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, A.; Deshmukh, S.G. Supply chain coordination: Perspectives, empirical studies and research directions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 115, 316–335. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Feliu, J.; Morana, J.; Grau, J.M.S.; Ma, T.Y. Design and Scenario Assessment for Collaborative Logistics and Freight Transport Systems. Int. J. Transp. Econ. 2013, 40, 207–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cagliano, R.; Caniato, F.; Spina, G. Lean, agile and traditional supply: How do they impact manufacturing performance? J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2004, 10, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, P. Co-ordination and integration mechanisms to manage logistics processes across supply networks. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2003, 9, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, E.; Othman, N. The factors influencing modeling of collaborative performance supply chain: A review on fresh produce. Uncertain Supply Chain. Manag. 2021, 9, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Khodaverdi, R.; Jafarian, A. A fuzzy multi criteria approach for measuring sustainability performance of a supplier based on triple bottom line approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshinder, K.; Kanda, A.; Deshmukh, S.G. A review on supply chain coordination: Coordination mechanisms, managing uncertainty and research directions. In Supply Chain Coordination under Uncertainty; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 39–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gammelgaard, B. The qualitative case study. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017, 28, 910–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchman, C.W.; Ackoff, R.L.; Arnoff, E.L. Introduction to Operations Research; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Ackoff, R.L. Optimization + objectivity = optout. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1977, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Feliu, J.; Chong, M.; Vargas-Florez, J.; de Brito, I.; Osorio-Ramirez, C.; Piatyszek, E.; Quiliche Altamirano, R. The maturity of humanitarian logistics against recurrent crises. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, V.E.J. El estudio de caso y su implementación en la investigación. Rev. Intern. Investig. Cienc. Soc. 2012, 8, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gharajedaghi, J.; Ackoff, R.L. Mechanisms, organisms and social systems. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Feliu, J. Considerations on Set Partitioning and Set Covering Models for Solving the 2E-CVRP in City Logistics: Column Generation and Solution Probleming Analysis. In Logistics and Transport Modeling in Urban Goods Movement; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 88–116. [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrieva, O.V.; Frolova, V.B.; Tyger, L.M.; Zokoev, V.A.; Ivanov, K.M. Economic and legal mechanism for the service enterprise operation. Nexo Rev. Cient. 2021, 34, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Análisis de las Principales Fuerzas Impulsoras Que Influyen en el Desarrollo del Sector Forestal Colombiano; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rapsomanikis, G. The Economic Lives of Smallholder Farmers: An Analysis Based on Household Data from Nine Countries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Martínez, F. Formas de Asociatividad Que Prevalecen en la Dinamización de las Cadenas Productivas Agrícolas en Colombia. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Lasalle, Bogotá, Colombia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilaky, K.; Martínez Sáenz, S.; Stanimirova, R.; Osgood, D. Perceptions of Farm Size Heterogeneity and Demand for Group Index Insurance. Games 2020, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajal, L.M.B.; Tovar, L.A.R.; Zimmerman, H.F.L. Model of associativity in the production chain in Agroindustrial SMEs. Contad. y Adm. 2017, 62, 1118–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, A.; Torero, M.; Donovan, J.; Horton, D. Agricultural innovation and inclusive value-chain development: A review. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 8, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.B. Las formas asociativas en la agricultura y las cooperativas. Estud. Agrar. 2009, 30, 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dentoni, D.; Bijman, J.; Bossle, M.B.; Gondwe, S.; Isubikalu, P.; Ji, C.; Kella, C.; Pascucci, S.; Royer, A.; Vieira, L. New organizational forms in emerging economies: Bridging the gap between agribusiness management and international development. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amusquibar, G. Apuntes sobre Asociativismo Rural en la Argentina y Mercosur. Buenos Aires: Centro Argentino sobre Estudios Internacionales; Centro Argentino de Estudios Internacionales: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Knoke, D. Organizing for Collective Action: The Political Economies of Associations; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).