4.1. Relationship Between Student Engagement and Academic Performance

Student engagement and academic performance are both highly variable and context-dependent factors. Given the absence of predefined classes or optimal clustering criteria, an exploratory cluster analysis was conducted to uncover patterns in the data. The objective was to identify natural groupings of students based on their interactions with the Learning Management System (LMS) and examine how these groupings relate to academic outcomes.

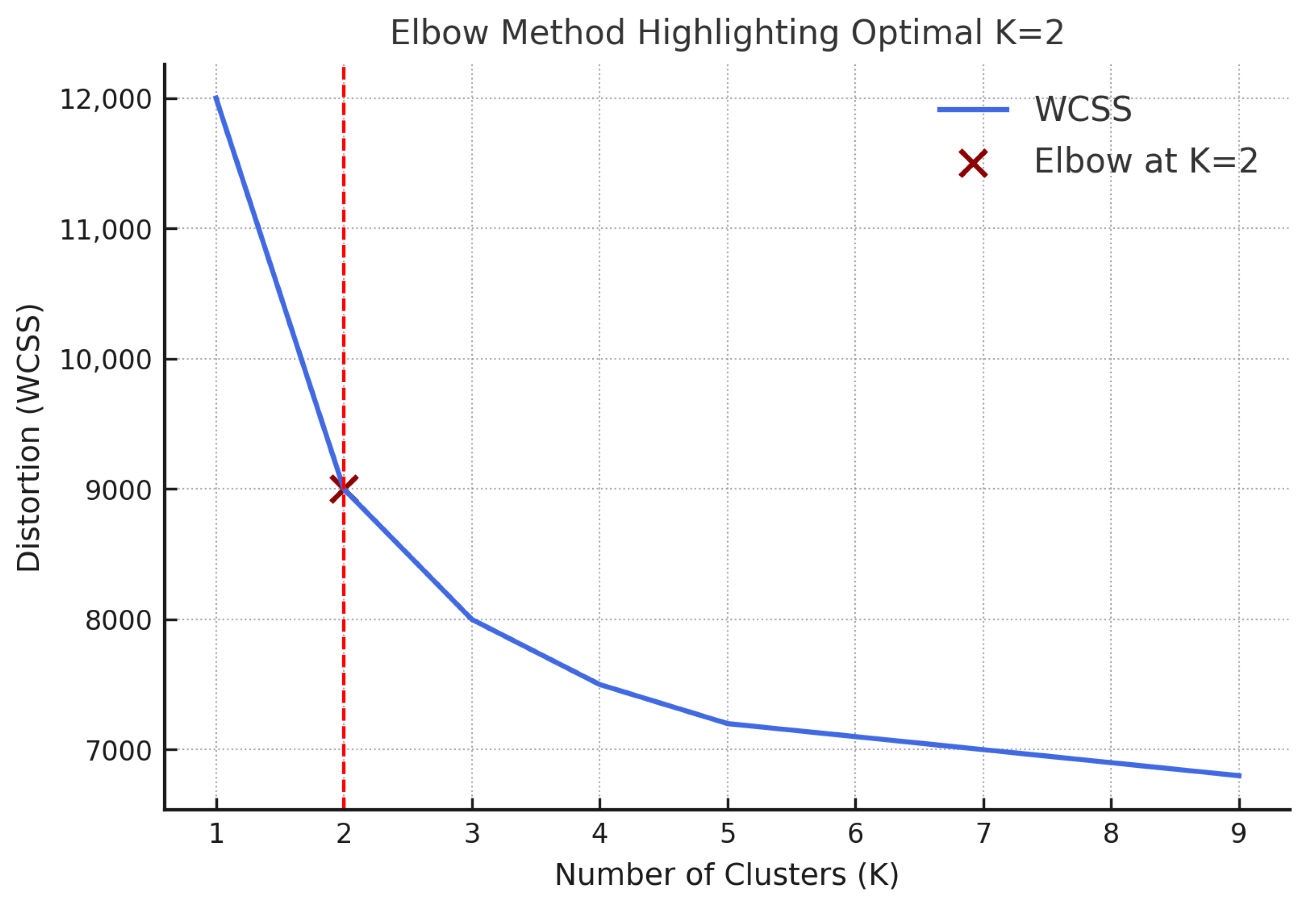

To determine the optimal number of clusters (K), the elbow method was employed by evaluating the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS) across K values ranging from 1 to 10. A pronounced bend at K = 2 in

Figure 2 indicated a significant reduction in WCSS, suggesting that a two-cluster solution best fits the data. The smaller bends at K = 3 and K = 6 hint at possible variations in learner behavior where a three-cluster model might capture a moderate engagement group, while a six-cluster model could reveal finer sub-profiles, such as video-focused or quiz-oriented learners. They were not considered substantial enough to warrant deviation from the two-cluster solution. Although not explored in this study, these alternative structures suggest promising directions for future research to better understand and support diverse engagement patterns.

Accordingly, four clustering algorithms were applied with K = 2: K-Means clustering (KM), Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC), Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM), and Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN). The models were evaluated using three standard cluster evaluation metrics:

Silhouette Score: Assesses how similar an object is to its own cluster compared to other clusters. Higher values indicate better-defined clusters.

Calinski–Harabasz Index (CH Index): Measures the ratio of between-cluster dispersion to within-cluster dispersion. Higher values suggest better performance.

Davies–Bouldin Index (DB Index): Evaluates the average similarity between each cluster and its most similar one. Lower values are preferable.

Each model was compared pairwise to determine the best-performing approach. Initially, AHC was compared to the GMM. AHC outperformed the GMM in both the Silhouette Score and CH Index, indicating denser and better-separated clusters, despite having a slightly higher DB Index. Consequently, AHC was selected to proceed to the next comparison stage against DBSCAN. The results of each comparison cycle are shown in

Table 3.

DBSCAN achieved the highest Silhouette Score, suggesting well-separated clusters. However, it performed poorly on the CH and DB Indices, making its overall performance inconsistent. Given this, both AHC and DBSCAN were compared to K-Means for final selection.

K-Means surpassed both AHC and DBSCAN across all metrics: it recorded the second-highest Silhouette Score (0.219318), the highest CH Index (244.933881), and the lowest DB Index (1.954872). These results reflect K-Means’ effectiveness in generating distinct and compact clusters with minimal overlap, making it the most suitable algorithm for this dataset.

To identify patterns of student engagement early in the course, we applied K-Means clustering to interaction data and assignment scores collected during the first two weeks of instruction. The K-Means algorithm was applied with K = 2, chosen based on the elbow method and silhouette analysis. The clustering revealed two distinct student groups:

Cluster 1: Low-engagement group with minimal LMS activity and content interaction, with low or no forum engagement.

Cluster 2: High-engagement group with high frequency of LMS logins and resource views, and active participation in discussion forums.

Interestingly, students in the high-engagement cluster demonstrated higher assignment scores during the first two weeks, whereas the low-engagement cluster consistently exhibited lower performance on early assignments.

The identified cluster labels were subsequently employed to examine the association between student engagement and long-term academic performance. For this purpose, final exam grades were consolidated into two categories—high performance and low performance—according to the grade classification presented in

Table 4. Grades classified as Excellent and Good (i.e., A+, A, A−, B+, and B) were grouped under the high-performance category, while all remaining grades were categorized as low performance.

Following the analysis, only three distinct relationships between student engagement and academic performance were identified: (1) high engagement–high performance, (2) low engagement–high performance, and (3) low engagement–low performance.

Accordingly, only three types of students could be categorized based on the intersection of their engagement level and academic outcomes. The distribution of these student groups within the dataset is presented in

Table 5.

Notably, no students with high engagement and low performance were observed in the entire dataset. This absence is a remarkable finding in the context of online education. It reinforces the critical role of sustained student engagement as a key success factor in improving academic outcomes in digital learning environments. At the same time, it is important to further assess the depth and quality of learning, moving beyond reliance on purely quantitative engagement indicators.

4.2. Performance Prediction Model

A student performance prediction model was developed using interaction log data from the Moodle learning management system, along with students’ academic performance data. The dataset, which had already undergone cleaning, scaling, and balancing, included the “result” column in categorical format. Since most machine learning algorithms require numerical input, the categorical grades in the result column were converted to numeric values using the label encoding technique, as outlined in

Table 4. Each grade was assigned an integer value from 10 (A+) to 0 (F, I, P, N).

To ensure the features were on a comparable scale, standardization was applied using the StandardScaler function from the Scikit-learn library. This process centers the dataset by transforming each feature to have a zero mean and unit standard deviation. Mathematically, standardization is defined as

where

is the transformed variable,

x is the original value,

is the mean of the feature, and

is the standard deviation. This transformation is crucial for improving the stability and convergence of machine learning models.

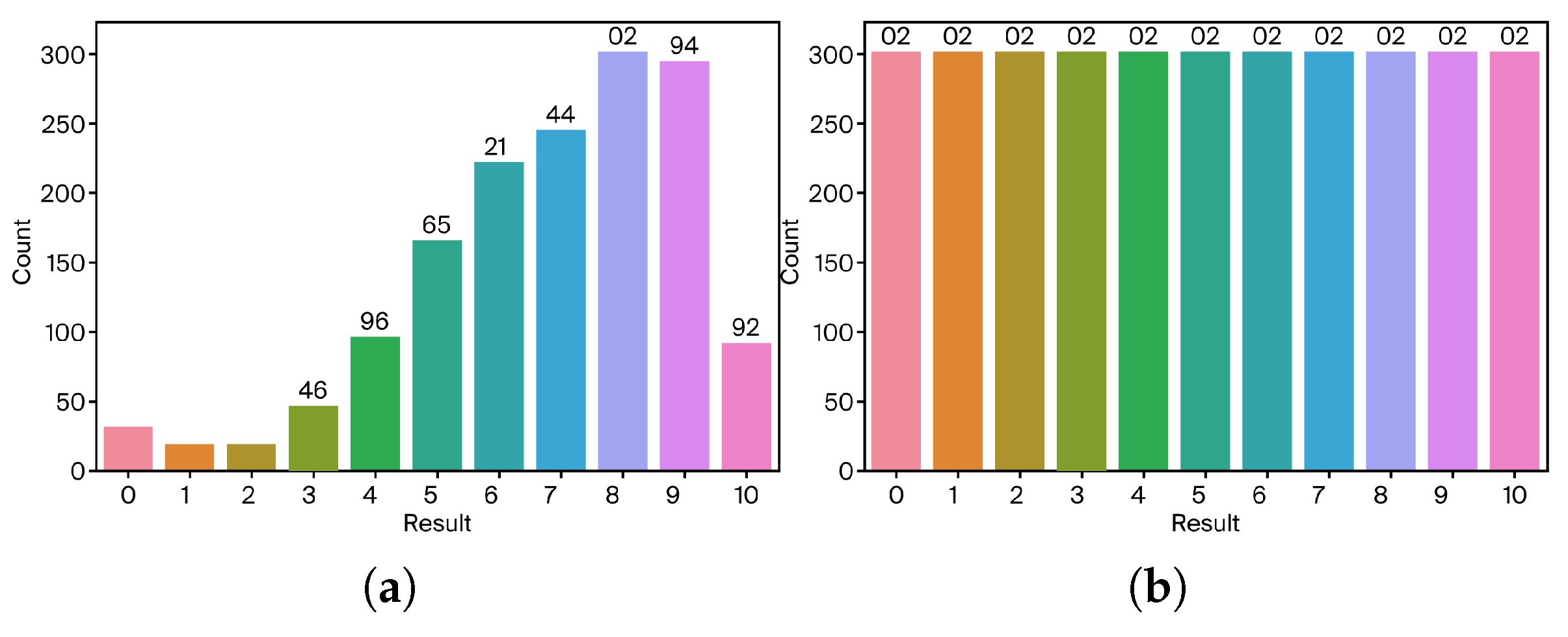

An initial examination of the dataset revealed a significant class imbalance among the target categories in the result column. Such imbalances can adversely affect model training by biasing predictions toward the majority class and reducing sensitivity to minority classes. To address this issue, we employed the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE), a widely used oversampling method for managing imbalanced datasets.

The SMOTE works by generating synthetic examples for the minority class based on the feature space similarities between existing minority instances. This approach improves the balance between classes without simply duplicating existing data, thereby helping machine learning models generalize better. The application of the SMOTE was conducted after feature scaling and label encoding, ensuring that the synthetic data aligned with the original data distribution. The distribution of classes before and after the application of SMOTE is shown in

Figure 3.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a widely used dimensionality reduction technique that identifies patterns in data by analyzing the correlation among features and emphasizing variance. PCA enables the reduction in the feature space while retaining the most significant information. In this study, PCA was used to determine the optimal number of components that can be retained without a substantial loss of information.

The dataset included data from five different course modules, each containing varying numbers of submission records. Since these variations could contribute disproportionately to the total variance and potentially bias the model, the number of submissions was normalized to a scale of 10, rather than treating each module submission as a distinct feature. This normalization ensured consistency across modules and improved the effectiveness of PCA.

Before training, the dataset was split into training and test subsets using the train-test-split() function from the Scikit-learn library. Machine learning models were trained on the training set, and their performance was evaluated on the test set. The model achieving the highest classification accuracy was selected as the optimal model for downstream system development.

To assess the impact of oversampling and dimensionality reduction, each machine learning model was tested with and without applying SMOTE and PCA techniques. The resulting accuracies for all combinations are summarized in

Table 6.

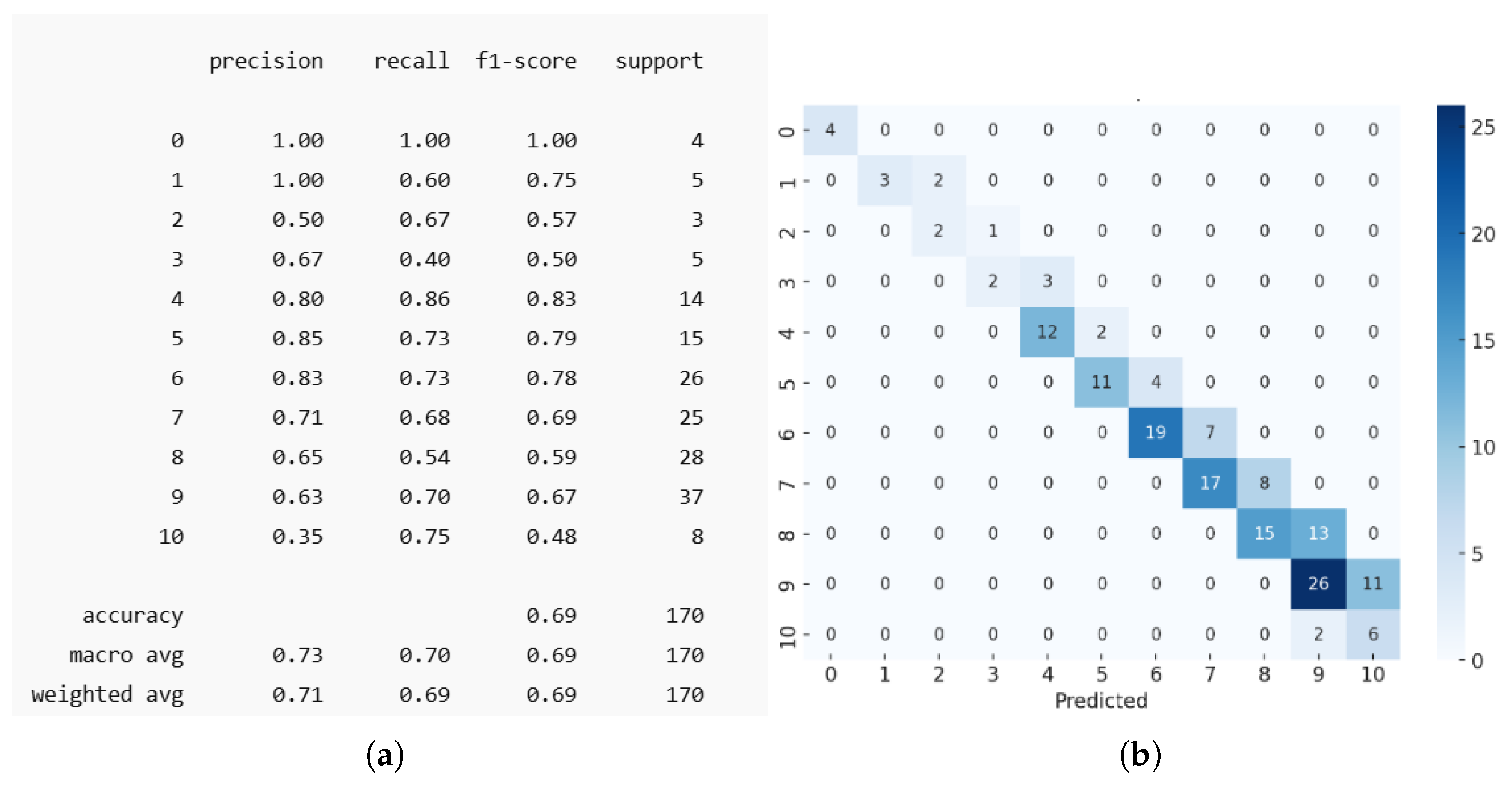

While accuracy provides a general measure of how many labels were correctly predicted by the model, it does not offer insights into class-specific performance. In imbalanced datasets, high accuracy may be misleading if certain classes dominate the predictions while others are neglected. Therefore, to achieve a more comprehensive evaluation of the classification model, a confusion matrix and a classification report were generated, as presented in

Table 7.

These metrics allow for detailed analysis of precision, recall, and F1-score for each class, helping to identify which classes were well predicted and which were underrepresented in the model’s output.

The performance of the classification models under different preprocessing conditions is summarized in

Table 7. Among the tested models, the Support Vector Machine (SVM) achieved the best overall performance, with the highest accuracy (0.69) and average precision (0.73) when trained with the SMOTE and without PCA. This suggests that the SVM benefits significantly from oversampling techniques that address class imbalance, although the application of PCA slightly reduced its performance. Random Forest also showed consistently strong results across all conditions, with a slight improvement in accuracy and precision when the SMOTE was applied without PCA (0.66 and 0.65, respectively), indicating that this model is robust to variations in preprocessing.

As shown in

Figure 4, Classes 3 and 10 under-perform compared to others, having an F1 score below 0.5. Mid-range classes (4 to 9) perform reasonably well. Classes 0 and 1 perform considerably well, despite the limited number of cases in each class.

In contrast, Softmax Regression exhibited the lowest performance across all metrics. Interestingly, it performed slightly better without the SMOTE and PCA, achieving 0.50 in both accuracy and average precision, while the SMOTE tended to degrade its results. XGBoost showed an opposite trend compared to the SVM; its best performance was observed without the SMOTE but with PCA (accuracy of 0.58 and precision of 0.63). The application of the SMOTE negatively impacted XGBoost’s performance across all evaluated metrics.

Overall, the results highlight that the effectiveness of preprocessing techniques, such as the SMOTE and PCA, varies by model. While the SVM and Random Forest benefited from oversampling, PCA did not consistently improve performance. These findings underscore the importance of model-specific tuning when handling imbalanced and high-dimensional educational datasets.

4.3. Study Plan Recommendation

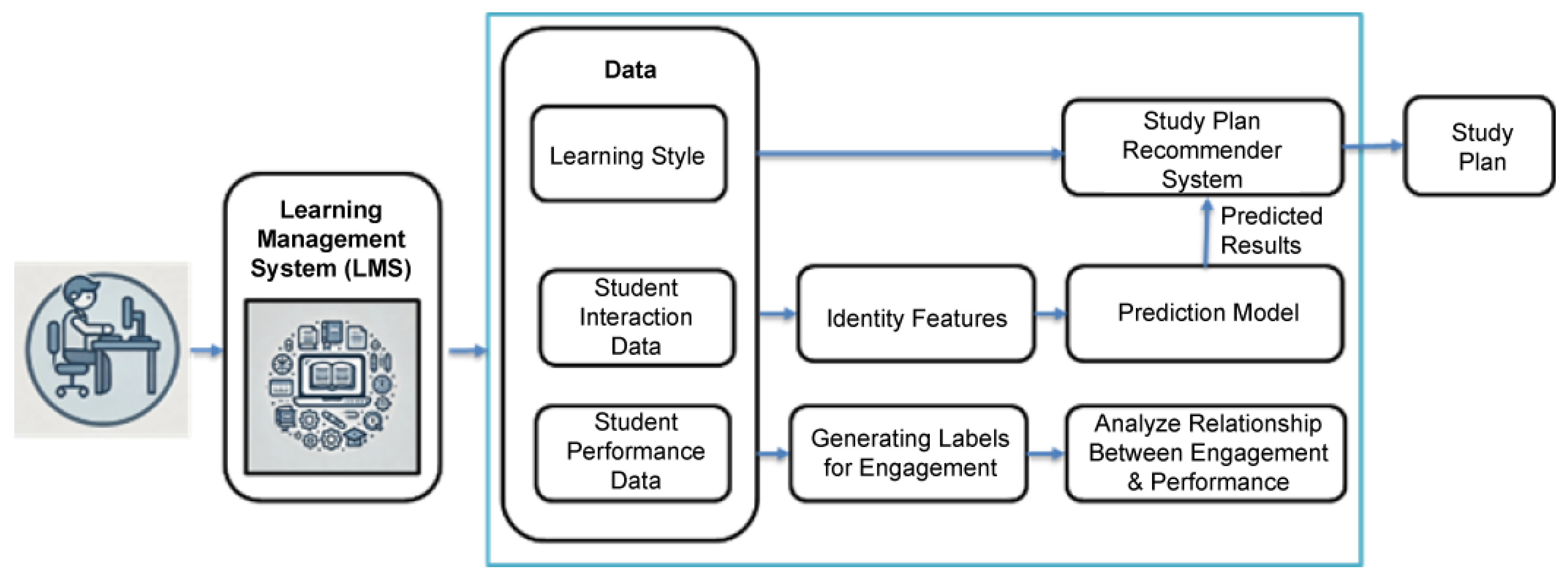

The study plan recommender system was designed to utilize multiple input sources, including student interaction data from the Learning Management System (LMS), predicted academic performance, and each student’s learning style. Interaction data were collected via the LMS, while predicted grades were passed from the previously trained performance prediction model. To determine students’ learning styles, the VARK questionnaire was administered to the same cohort of students for whom LMS interaction and performance data were available.

The integration of these data sources was performed in two stages using the student identification number as the common key. First, the interaction data collected for individual course modules were manually combined into a single dataset. This manual preprocessing step was required due to the one-time nature of the data and the non-repetitive structure of each module. Second, learning style data collected through Google Form submissions were decoded from the exported CSV format. Each student’s VARK scores were derived by analyzing their questionnaire responses using a custom Python script. The script computed the individual scores for Visual, Aural, Read/Write, and Kinesthetic modalities and generated a dataset mapping each score to the student’s identification number. In cases where a student was enrolled in multiple modules, their corresponding VARK scores were mapped to each related interaction record.

Since the recommender system is expected to predict study plan outputs as interaction patterns, a well-prepared training dataset was crucial. The output labels were structured for binary classification, indicating the presence or absence of recommended patterns. Given that the recommender system performs multi-label binary classification, additional data transformations were required. The student’s desired grade, provided as text, was encoded numerically using the scale defined in

Table 4, where A+ corresponds to 10 and failing or incomplete grades to 0.

Furthermore, student interaction features, which varied across numeric ranges, were binarized to standardize their influence in the model. Each interaction metric was transformed into a binary variable depending on whether it exceeded the mean value across the dataset. This ensured that the model could clearly identify whether a particular interaction was meaningfully expressed by the student.

To identify the most effective model for generating personalized study plans, two machine learning algorithms were tested: the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNNs) classifier and a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). Both models were evaluated using the Hamming loss metric, which is appropriate for assessing performance in multi-label binary classification tasks. The evaluation results are summarized in

Table 8.

The results clearly indicate that the KNN classifier outperforms the CNN model, achieving significantly lower Hamming loss values across the dataset. Due to its superior performance and lower computational complexity, the KNN model was selected as the underlying engine for the implementation of the study plan recommender system.

While the KNN outperformed the CNN in terms of Hamming loss, this may reflect the nature of the dataset and feature space. The KNN is well suited for structured, tabular data with limited samples, whereas CNNs generally require larger datasets and spatially structured inputs to perform optimally. Future studies could revisit this comparison with expanded datasets and additional feature engineering to test whether deep models capture further nuances.

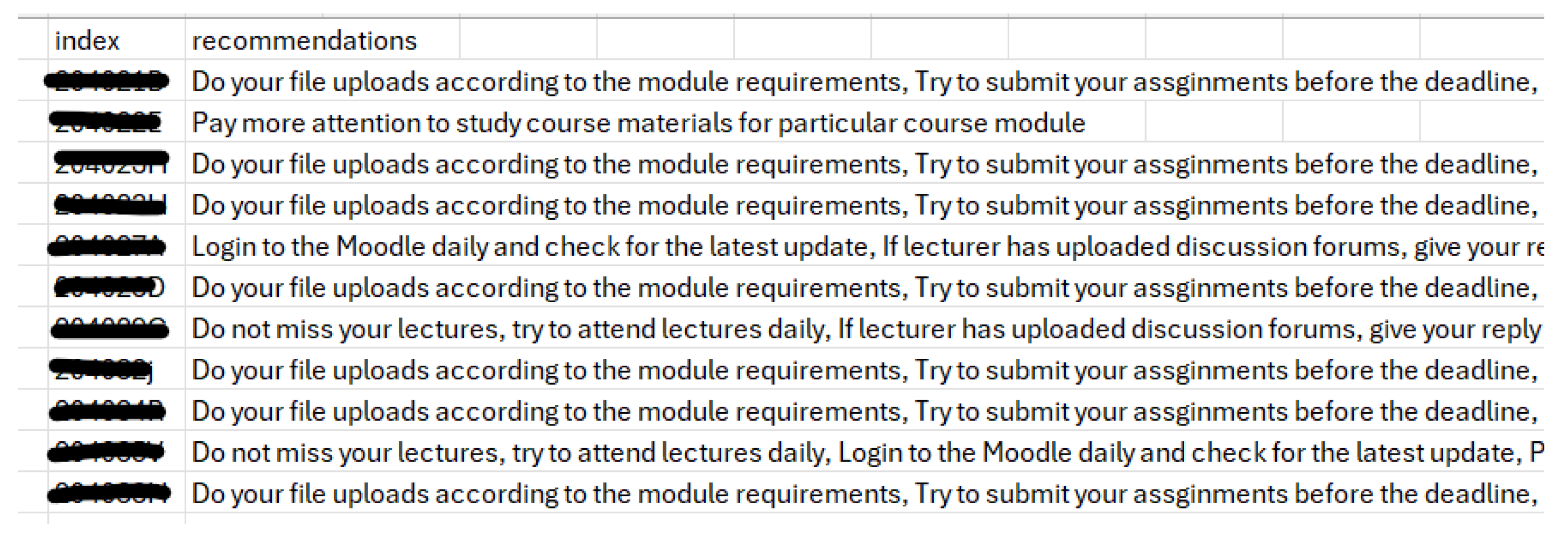

The study plan recommendations are generated using the trained KNN model. The process outlines the full pipeline—from accepting new input data to writing the final recommendations into a structured CSV file. A sample output of a CSV file, containing recommended study plans for several students, is displayed in

Figure 5.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed study plan recommender system, a controlled experiment was conducted using a custom-hosted Moodle platform. The platform simulated a semester-long learning program for an HTML course, with participation from 250 undergraduate students of the Faculty of Information Technology, University of Moratuwa. To incorporate individual learning preferences into the system, the VARK questionnaire was distributed among all participating students to collect data on their learning styles.

From this cohort, a subset of 30 students was selected and randomly divided into two groups. The experimental group received personalized study plan recommendations following their performances in Quiz 1 and Quiz 2, while the control group continued learning without any system-generated study guidance. Both groups proceeded through the remainder of the course under these conditions.

At the end of the course period, a final quiz was administered to all 30 students to assess learning outcomes. The predicted results, based on the machine learning performance model, and the actual quiz scores were recorded for each student in both groups. The difference between actual and predicted results was computed using the encoded grade values defined earlier (

Table 4), with point deviation calculated as the difference between actual and predicted grade values.

The results for the control group (students without recommendations) and the experimental group (students with study plan recommendations) are presented in

Table 9 and

Table 10, respectively. The comparison aims to measure the impact of the study plan recommender system on academic improvement over the baseline predicted outcomes.

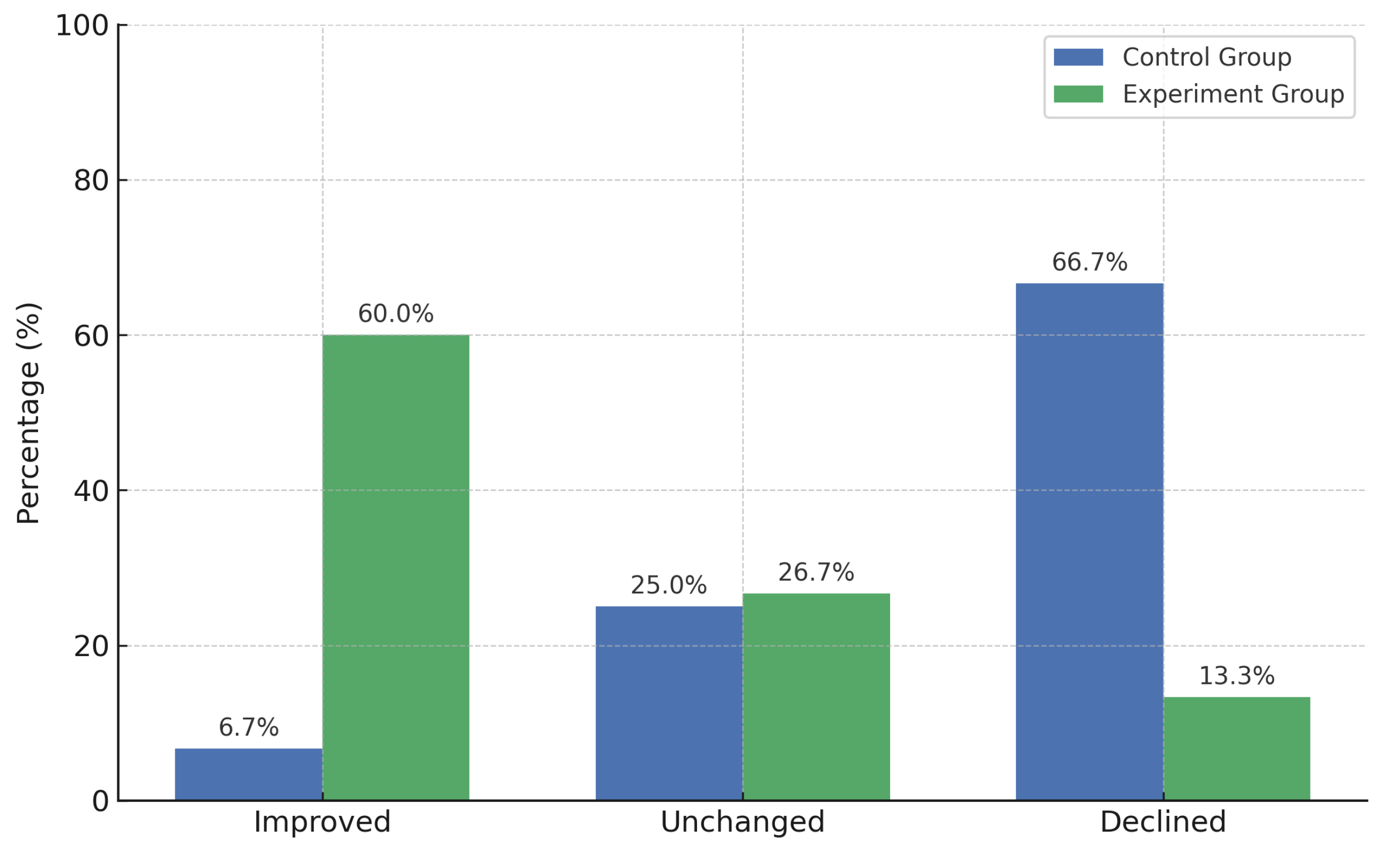

An analysis of the performance deviation among the control group revealed that 66.67% of the students experienced a decline in performance compared to their predicted grades. Only 6.67% of students showed an improvement, while 25% maintained their originally predicted performance level. These findings suggest that, in the absence of personalized study plan recommendations, the majority of students failed to meet their expected academic outcomes, with a notable tendency toward performance decline.

The results from the experiment group—students who received personalized study plan recommendations—demonstrate a significant improvement in academic performance. As shown in

Table 10, 60% of the students achieved higher actual grades than their predicted results, while 26.67% maintained the same performance level. Only 13.33% of the students exhibited a slight decline in performance.

These findings contrast sharply with the control group, in which the majority of students experienced a decline in academic performance. In contrast, a significantly higher proportion of students in the experiment group demonstrated improved outcomes. This observation is further supported by the comparative analysis illustrated in

Figure 6, where the performance deviations between the control and experiment groups are visually contrasted.

The high percentage of performance improvement in the experiment group strongly suggests that the study plan recommender system had a positive impact on student learning outcomes, particularly benefiting those students who were previously predicted to perform at lower levels.

4.3.1. Statistical Analysis of Intervention Effectiveness

To evaluate the effectiveness of the personalized study plan recommendations, an independent two-sample t-test (Welch’s t-test) was conducted. This test compared the deviation between predicted performance and actual final quiz scores for two groups:

The performance difference was calculated as

A positive difference indicates the student outperformed the prediction; a negative difference indicates underperformance.

4.3.2. Descriptive Statistics and t-Test Results

Table 11 summarizes the key statistics for each group. Note that the t-statistic and

p-value describe the statistical relationship between the two groups and are therefore not specific to either one individually.

Since the p-value is less than 0.05, the result is statistically significant. We conclude that the personalized study plan recommendations led to a meaningful improvement in student performance.

4.3.3. Box Plot Interpretation

Figure 7 illustrates a box plot comparing the distribution of performance differences between the two groups. Students who received personalized recommendations exhibited more consistent achievement levels and frequently surpassed their predicted grades. In contrast, those without recommendations tended to underperform and showed greater variability in outcomes. These patterns are consistent with the statistical analyses, reinforcing the hypothesis that tailored study support contributes to improved learning performance. The observed improvements further reflect the system’s primary objective—delivering personalized academic guidance based on individual learning styles and interaction behaviors—highlighting its potential effectiveness in authentic educational settings.