1. Introduction

The scientific literature describes how Machine Learning (ML) assists service quality management. Research identifies several ways these algorithms enhance service provider management, including the development of predictive customer satisfaction systems and the analysis of key satisfaction features [

1,

2,

3].

This diversity of applications arises from the characteristics of the service industry itself, which can be subdivided into transportation, communications, hospitality, and healthcare, among others [

4]. Each of these sectors has its own specific management methods, operations, and end products. However, all service providers share a common objective: meeting consumer expectations through effective planning, failure analysis, and quality improvement [

5].

Unlike a physical product, whose quality can be measured concretely, service quality is harder to assess because it is intangible [

6]. To address this, Altuntas and Kansu [

5] suggest managing service quality by aligning expectations with perceived value, planning effectively, and reducing failures. Further, the literature shows customer satisfaction is linked to higher retention and loyalty [

7,

8].

This has led companies and regulatory agencies to develop methods for obtaining customer satisfaction data. Commonly, questionnaires such as SERVQUAL measure quality via tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy [

9,

10]. The Net Promoter Score (NPS) measures satisfaction on a 0–10 scale and classifies customers as detractors, neutrals, or promoters [

11,

12]. Sentiment analysis of online reviews [

13] and social media [

14] offers alternative ways to assess satisfaction.

Recent literature demonstrates the wide range of applications of machine learning models focused on customer satisfaction and service quality. For example, studies can be found in the fields of tourism and hospitality [

15,

16,

17], financial institutions [

18,

19,

20,

21], aviation [

22,

23,

24,

25], product design [

26,

27,

28], e-commerce [

29,

30,

31,

32], and distribution logistics [

33,

34], with the objective of predicting churn, complaints, analyzing sentiment in reviews, and understanding factors related to customer retention and loyalty. In the telecommunications field, works such as [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45] are the most recent found in the literature and will be described later.

The telecommunications sector encompasses internet service providers (ISPs) involved in fixed-line telephony, mobile telephony, broadband, and pay-TV services [

46]. The academic literature on the telecommunications sector covers articles applied to streaming video transmission quality, customer retention, complaints predictions, analysis of the most relevant features, construction of automated systems for customer satisfaction classification and prediction, among others [

47,

48,

49,

50].

Despite abundant international literature, few Brazilian publications focus on using ML to study service quality. Rožman et al. [

51] and Grebovic et al. [

52] argue that ML models outperform traditional statistical models on nonlinear datasets due to higher accuracy. Some Brazilian applications exist, such as Sibert et al. [

2] on predictive customer satisfaction in energy, and Lucini et al. [

25] on ML-driven analyses of air transport customer satisfaction. These examples illustrate ML’s potential in enhancing Brazilian service quality management.

Despite the limited number of national publications, Brazil has been developing databases that could be explored. The National Telecommunications Agency (ANATEL) conducts an annual nationwide survey to gather information on customer satisfaction indices for mobile telephony and broadband services [

46]. The resulting database from this survey is publicly available, but few scientific works have used this dataset for research. In the literature, two studies explore these data, focusing on customer satisfaction with telephony services; however, neither addresses customer satisfaction with broadband services [

53,

54].

Considering the challenges and importance of service quality, the potential benefits that machine learning (ML) techniques can offer to this domain, the scarcity of publications in Brazil, and the availability of data from ANATEL, this research presents a novel approach that applies machine learning and explainable artificial intelligence techniques to analyze and interpret models related to customer satisfaction with internet services in Brazil. Specifically, ML techniques were employed to classify customer satisfaction, and the most relevant features influencing the outcomes were subsequently investigated using the explainable artificial intelligence method SHAP (SHapley Additive eXplanations), in conjunction with algorithms such as Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), and Gradient Boosting (GB).

Accordingly, this article makes three main contributions:

The exploration of ANATEL data on the quality of broadband internet service providers, which are publicly available at the national level, is released periodically, and based on reliable measurements, yet remains underexplored in the literature.

Application of ML algorithms to predict (in this case, classify) customer satisfaction, assessing the contribution of variables to deepen the understanding of the most relevant predictors through strategies embedded in tree-based algorithms, as well as SHAP, which provides a global interpretation of the models. This enhances model transparency and interpretability [

55], representing a strong alternative to traditional statistical approaches.

Using the Net Promoter Score (NPS) as a reference value to operationalize customer satisfaction monitoring, as noted by [

56], enhances the applicability of classification algorithms and the interpretability of the models. Additionally, the NPS categories were adapted to examine model training behavior and the predictive power of the algorithms under different categorization schemes.

The remainder of this article is organized into six additional sections.

Section 2 (Theoretical Background) discusses the concepts of customer satisfaction, NPS, ML algorithms, and explainable artificial intelligence.

Section 3 (Literature Review) presents prior studies on the application of ML across various service sectors.

Section 4 (Materials and Methods) details the entire research process, from data characteristics and extraction to the application and analysis of the techniques.

Section 5 (Results) reports the performance of the classification techniques and identifies the most relevant features.

Section 6 (Discussion) provides a synthesis of the findings. Finally,

Section 7 (Conclusions) presents the conclusions derived from the data and research objectives, along with directions for future research.

3. Literature Review

The earliest relevant studies applying machine learning (ML) to customer satisfaction in telecommunications date back to 1995 [

75] and 1996 [

76]. The former was conducted in partnership with the telecommunications company US WEST and the University of Colorado, using the KnowledgeSEEKER software (version 3.0) to analyze customer data, with a focus on classifying service quality through tree-based techniques. The second study is closely related to the first but places greater emphasis on decision-tree-based strategies aimed at cost reduction. In this case, the most relevant factors were modified due to issues related to the company’s competitive environment.

As previously noted, numerous studies have been published on ML applications focusing on customers in the telecommunications sector. Pacheco et al. [

35] proposed an approach to internet traffic classification using ML and deep learning models to improve Quality of Service (QoS). This application was more technical in nature, addressing internet protocols and satellite communications, and classified traffic using algorithms such as k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Decision Tree (DT), Extra Trees, Ensemble Voting, and AdaBoost, with automatic feature extraction via one- and two-dimensional convolutional neural networks (1-D and 2-D CNNs).

Some studies explicitly used customer satisfaction as the target variable. For example, Wassouf et al. [

36] adopted a predictive big data approach to analyze customer loyalty in Syria, focusing on the Syriatel Telecom Company. Based on 127 million records, users were segmented into groups, and loyalty was measured for each segment. Classifiers such as Random Forest (RF), DT, Gradient-Boosted Machine (GBM), and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) were employed. A total of 223 features—covering customer segments, individual behavior, social and spatial aspects, and service and contract types—were used. The binary classification achieved accuracies of up to 87% and a precision of 76%, while multiclass models yielded lower accuracy.

Internet speed was the focus of Namlı et al. [

37], who proposed a framework using ANN classifiers (multilayer perceptron and radial basis function network types) for initial problem detection, followed by clustering with Kohonen networks and Adaptive Resonance Theory to identify issues, and concluding with a bagging ensemble for both classification and clustering. Principal Component Analysis was applied to reduce dimensionality in a dataset originally containing over 33,000 instances and 270 variables from a call center, and class-balancing strategies were used, achieving accuracies of up to 92%. Espadinha-Cruz et al. [

38] proposed a methodology to improve lead management efficiency and increase customer acquisition in a telecommunications company. Using a dataset of more than 546,000 records and 18 variables, each instance was classified into probability ranges of potential customer conversion using ANN, DT, GBM, and ensemble-based algorithms. Ensemble models showed errors below 0.17.

YahYah et al. [

39] classified customer trouble tickets in a telecommunications company to improve operational efficiency. The study was conducted across several company units in Malaysia and used data including creation date, speed, type, status, internet signal strength, configuration, response time, and customer characteristics. Natural Language Processing (NLP), SQA-based data selection, and data mining techniques were applied. Average accuracies of 75.35% were achieved using single-machine boosting ensemble models, while a Hadoop-based DT system reached an average accuracy of 84.86%. Rintyarna et al. [

40] analyzed Twitter data to understand customer perspectives on internet service quality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using sentiment analysis and Naïve Bayes (NB) classifiers on datasets from two Indonesian companies, the proposed framework achieved accuracy slightly above 80%, recall of approximately 90%, and precision around 75%, with positive and neutral sentiments predominating.

Haq et al. [

41] investigated factors affecting 3G and 4G telecommunication services in Punjab, Pakistan, analyzing network coverage, customer service, video calls, and download speed using descriptive statistics, correlation, and regression analysis. With data from 300 respondents, results indicated that internet speed was the most important factor for increasing company revenues in the region. Saleh and Saha [

42] examined customer retention through churn analysis using four datasets, including one collected in person at Aalborg University. Models such as RF, AdaBoost, Logistic Regression (LR), DT, and Extreme GBM were applied. RF, AdaBoost, and XGBoost achieved the best performance on this dataset, with accuracies above 90%. Feature importance analysis highlighted package upgrades as key for the Aalborg dataset, while contract type, monthly charges, and service stability were more relevant in other datasets.

Afzal et al. [

43] applied classification algorithms to predict churn in a telecommunications service company using RF, KNN, DT, and XGBoost, achieving test accuracies of up to 98.25%. Variables included internet service types, device protection plans, online security and backup, contract types, and demographic factors. However, a limitation of this study is its reliance on a single, well-known dataset available on the Kaggle platform. Chajia and Nfaoui [

44] also addressed churn prediction, leveraging large language model embeddings and classifiers such as LR, SVM, RF, KNN, ANN, NB, DT, and zero-shot classification. Using a Kaggle dataset with nearly 37,000 customers, including demographic, spatial, customer category, preferred offers, operations, internet options, discounts, and complaints, the authors found that embeddings from OpenAI combined with LR achieved 89% accuracy and an average F1-score of 88%. Finally, AbdelAziz et al. [

45] analyzed churn data using ML and deep learning models applied to Customer Relationship Management (CRM) data from insurance, internet service provider, and telecommunications companies. Using XGBoost, CNN, and deep learning ensembles, accuracies of up to 95.96% for insurance and 98.42% for telecommunications were achieved.

There is also a substantial body of literature addressing service quality and customer satisfaction in telecommunications. Cox and Bell and Cox et al. [

75,

76] used Decision Trees to classify mobile telephony customer satisfaction based on perceived quality questionnaires and demonstrated how DTs can extract the most relevant features influencing satisfaction.

Specifically, regarding the use of the Net Promoter Score (NPS) in telecommunications, authors such as Tong et al. [

49] and Markoulidakis et al. [

77] used questionnaire data and treated NPS as the output variable in ML applications. Tong et al. [

49] applied XGBoost and DT models to consumer information, pricing, usage profiles, and behavior, finding that average call duration over the previous three months, average 2G internet traffic, and Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) were the most important variables for identifying customer loyalty. They also applied k-means clustering to segment customers into six groups aligned with business needs. In contrast, Markoulidakis et al. [

77] conducted extensive ML experiments to analyze the association between NPS and customer experience (CX). DT, KNN, SVM, RF, ANN, CNN, NB, and LR were applied to classify 10,800 surveys across two dataset versions: one with nine CX-related attributes and the class label, and another including an additional NPS bias variable. NB and CNN achieved the best F1-scores in the first version, while RF, ANN, and CNN performed best overall in the second version, reaching accuracies and precision of approximately 80%.

Suchanek and Bucicova [

78] modeled customer satisfaction in the Slovak telecommunications industry using structural equation modeling and identified a positive relationship between corporate image and perceived service quality, as well as a negative relationship between customer expectations and perceived quality, underscoring the importance of expectation–perception gaps. Abdullah et al. [

79] surveyed customers of telecommunications providers in Kurdistan and found that prices, network quality, and connectivity were the main drivers of satisfaction, concluding that value-added services did not affect quality perception.

Applications focused on telecommunications in Brazil remain limited. Study [

80] examined customer satisfaction in call center management within a telecommunications company using stepwise multiple linear regression, identifying “First-Contact Resolution Rate” and “Average Handle Time After the Call” as the variables most strongly associated with satisfaction. Alternative indicators closely related to satisfaction were also proposed, including responsiveness, abandonment rate, company satisfaction, and problem-solving capability. Siebert et al. [

2] investigated satisfaction prediction using DT, SVM, Gaussian process regression, ANN, and ensemble models applied to electricity distribution service data from COPEL, the utility responsible for this service in the state of Paraná. The dependent variable was an internal indicator used by the company, and regression models were evaluated using mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), yielding an average deviation of 1.36% from company-reported results.

Overall, this literature review highlights that Brazilian studies are scarce and generally focused on different scales or types of companies. While there is extensive research in the telecommunications sector, studies often rely on distinct independent variables and satisfaction indicators. Regarding NPS specifically, only two relevant articles were identified. Consequently, this research aims to address this gap by leveraging public, underutilized data to apply ML techniques, using the NPS to categorize the dependent variable (satisfaction) and incorporating variable importance analyses not presented in prior studies, particularly SHAP, a widely adopted and contemporary method compared to traditional statistical techniques and tree-based feature importance measures.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. ML Models

This research analyzes customer satisfaction with broadband services in Brazil. We used data from ANATEL’s annual nationwide survey, which covers all Brazilian states [

15]. The dataset’s overall customer satisfaction feature (“J1”) is the analysis’s target variable.

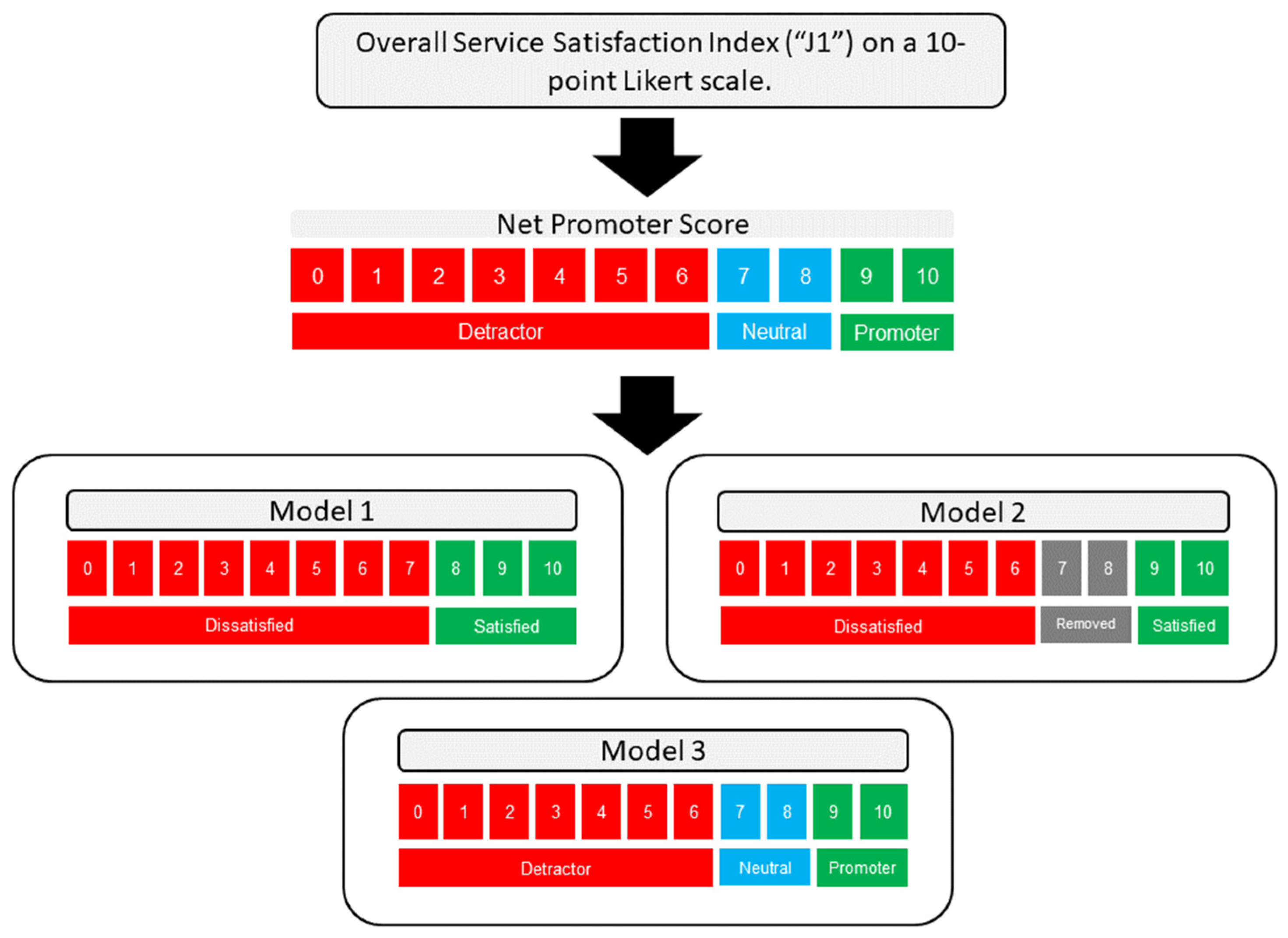

The NPS (Net Promoter Score) is an indicator used by service providers to assess customer loyalty [

81]. Customers are asked, “On a scale of 0 to 10, how likely are you to recommend a particular company to someone else?” Based on their responses, customers are classified into different categories: those who respond with a score of 9 or 10 are referred to as “Promoters,” those who respond with a score of 7 or 8 are labeled as “Neutrals,” and those who respond with a score of 0 to 6 are categorized as “Detractors” [

27]. Since the overall service satisfaction index is also on a 10-point Likert scale, the NPS was used as a reference to construct three classification models.

Although NPS is widely used, the literature contains articles that criticize its applications. Kristensen and Eskildsen [

82] compared NPS and other metrics using simulated data, showing that grouping into promoters, neutrals, and detractors can vary and may make the final indicator imprecise. The same authors also reported that the indicator lacked precision and that its use could lead to poor management decisions [

82].

Despite these issues with the NPS, Baquero [

64] argues that many companies ultimately use NPS in conjunction with additional questions in multidimensional questionnaires, balancing detailed assessments of products and services with the item related to customer loyalty. In the present study, considering the assertion that there are potential associations between customer loyalty and satisfaction [

69], and acknowledging that NPS alone is insufficient to analyze customer loyalty and business growth, as emphasized by [

82], the NPS scale classification (detractors, neutrals, and promoters) was adopted to categorize the score of interest representing overall customer satisfaction with the service analyzed in this work. This approach facilitates analysis within discrete groups by machine learning models.

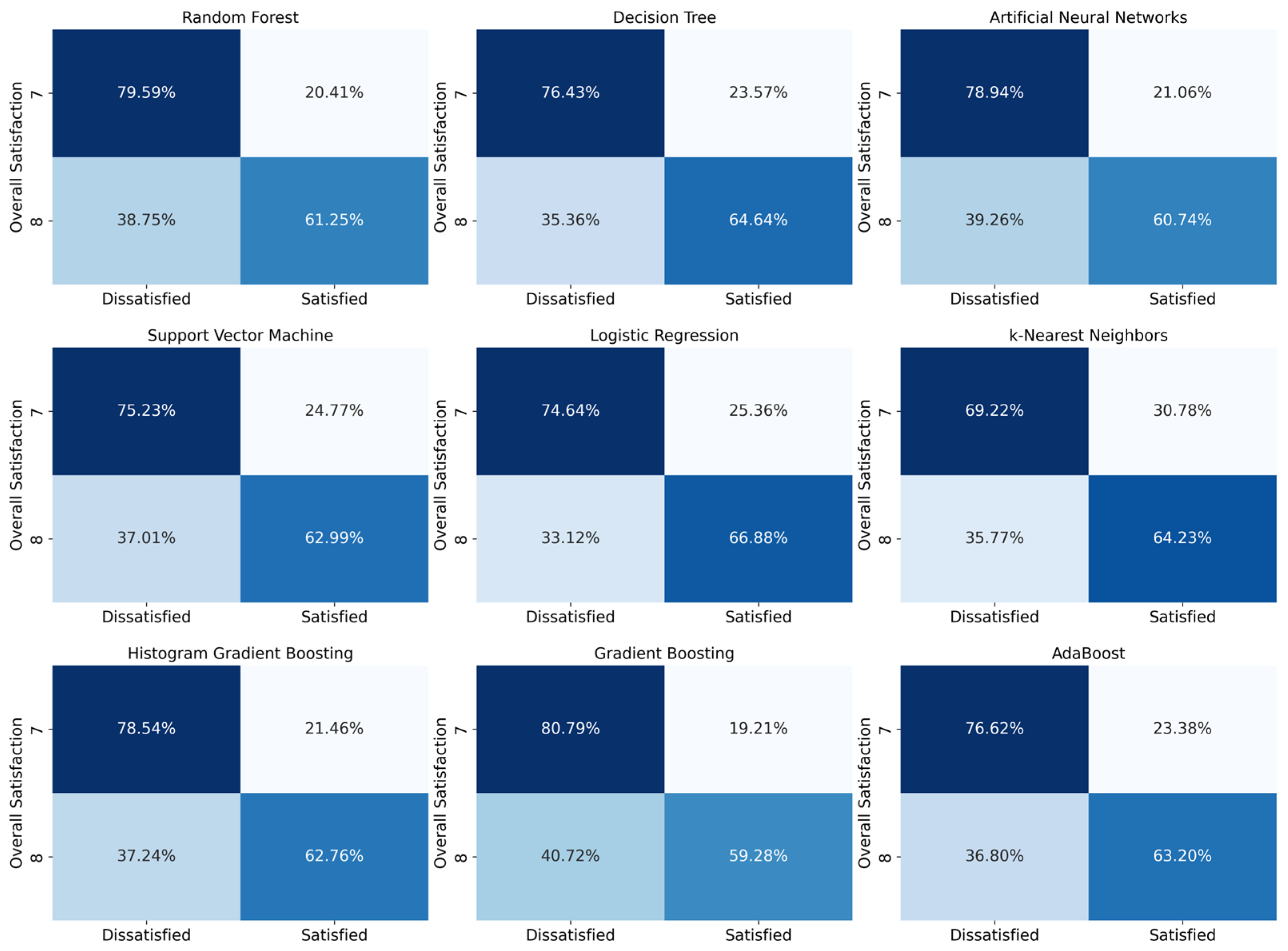

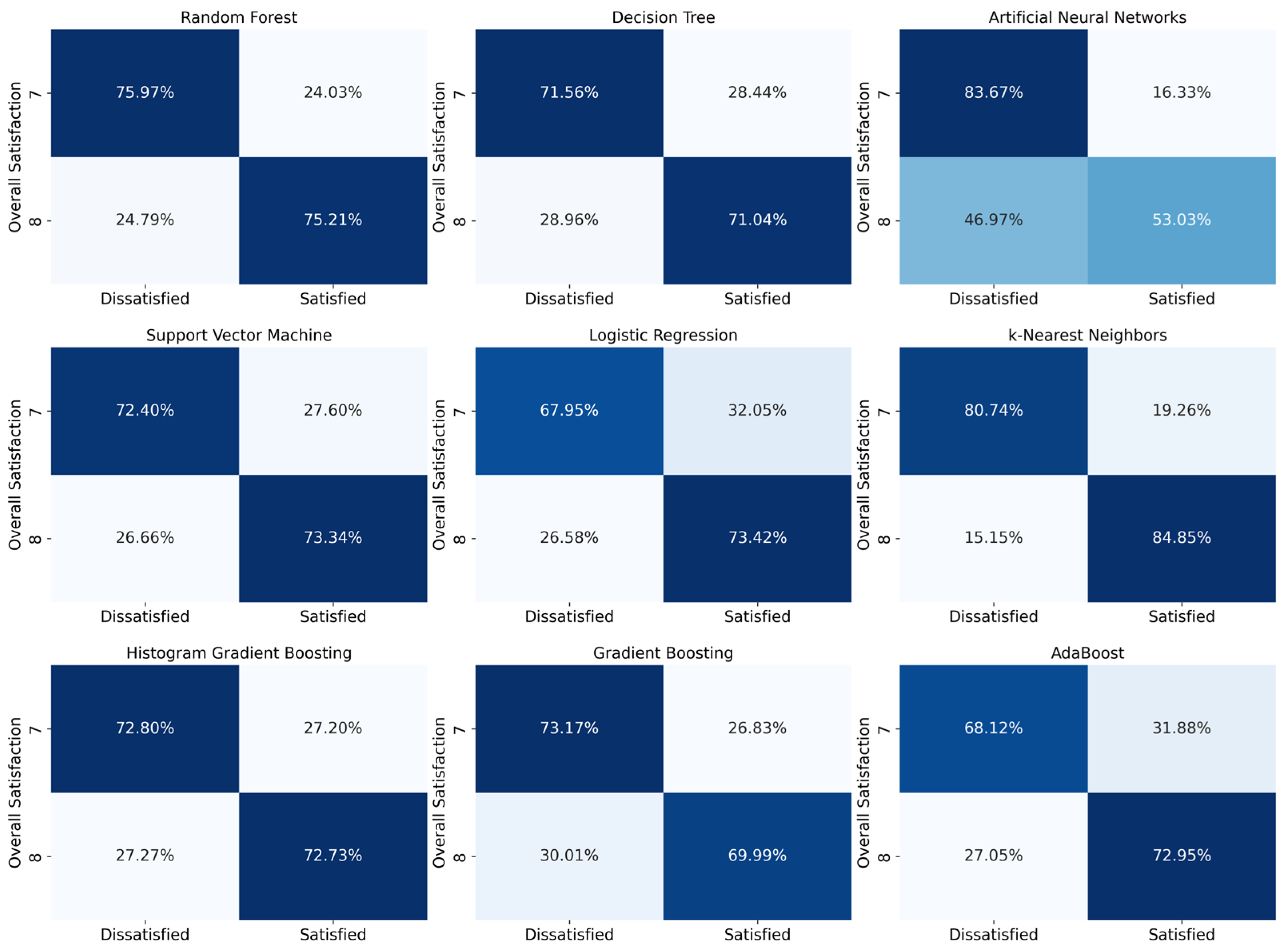

Figure 1 presents a description of the three models used in the research. Based on the NPS scale, each model was obtained by applying distinct strategies to convert respondents’ scores into satisfaction classes. Model 1 represents a binary classification dataset: customers who responded with a score of 8 or higher are classified as satisfied, and those with a score of 7 or lower are classified as dissatisfied. In Model 2, only the Detractor and Promoter classes of the NPS are considered, excluding the “Neutrals”. Therefore, all customers who scored 7 or 8 were removed, leaving only the two extreme categories. Finally, Model 3 considers all three NPS classes simultaneously.

In Model 1, customers who rated 8 are classified as satisfied, while those who rated 7 are classified as dissatisfied. Since customers rated as neutral by the NPS represent an uncertain group, Model 1 aimed to analyze the ML application by treating a portion of the neutrals as satisfied and another as dissatisfied. The results were essential for identifying the impact on the techniques’ performance and determining the most relevant features for classification.

Model 2, on the other hand, excludes neutral customers from the training dataset and therefore aims to analyze the impact on the techniques’ performance without considering these instances. Therefore, this model is important for understanding and exploring the profile of customers classified as neutral, comparing the data resulting from Model 1, and for analyzing how ML techniques classify these uncertain data according to their training criteria.

The objective of Model 3 was to apply ML using the full set of NPS subdivision criteria. Model 3 aimed to assess the performance of the techniques in classifying data into promoters, neutrals, or detractors. While Models 1 and 2 explore the inclusion or exclusion of neutrals in the dataset, Model 3 is relevant because it uses all NPS classes without manipulation and provides a comprehensive analysis of classification results for each category.

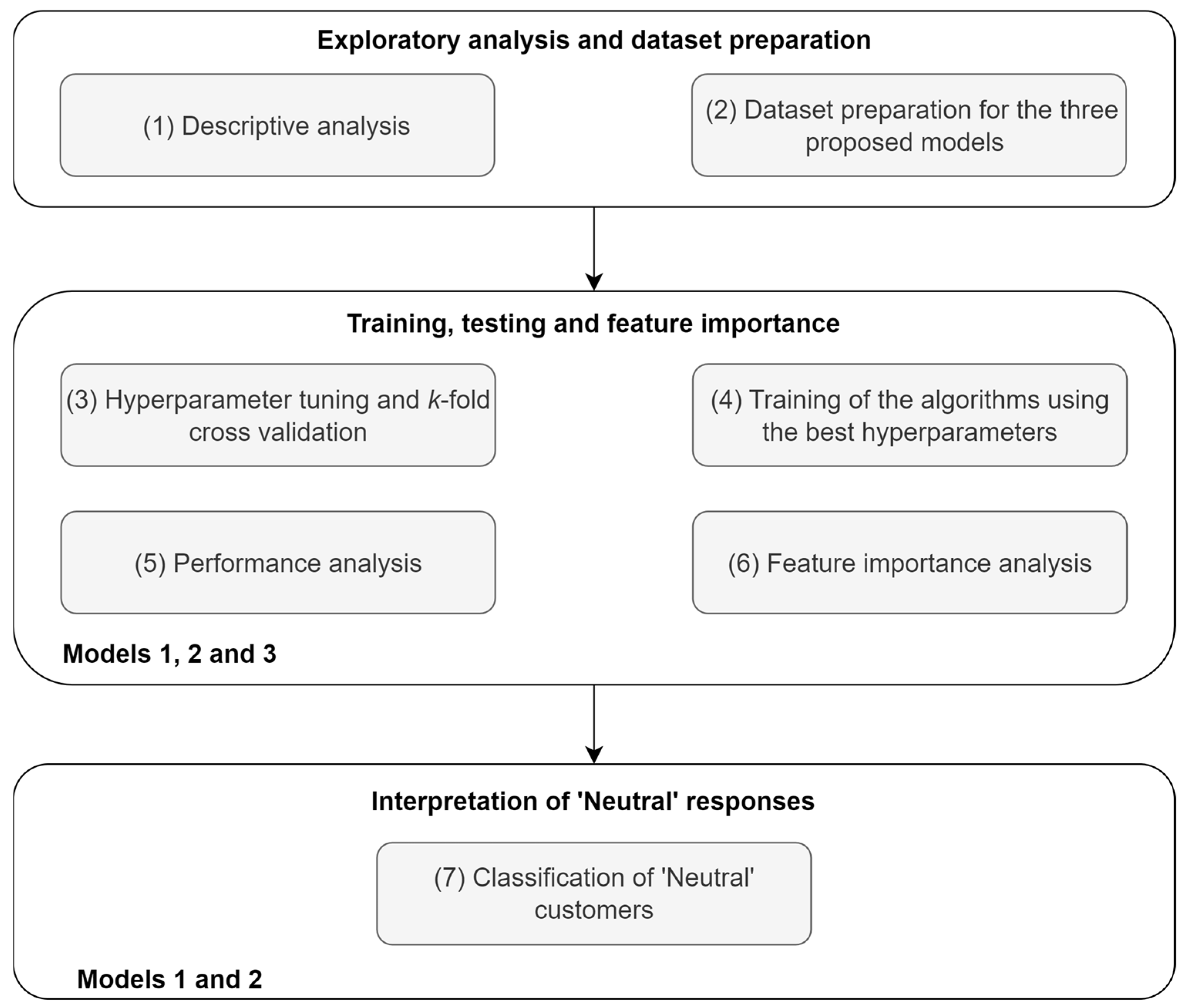

Figure 2 illustrates the overall research workflow. In line with the general objective of analyzing customer satisfaction with broadband services in Brazil through the application of machine learning (ML) techniques to ANATEL data, the study was structured into three main stages: (1) Dataset preparation, where the data were explored and pre-processed for the next phase, (2) Application of ML algorithms, where the techniques were trained and tested in all models. Finally, (3) an analysis of neutral customers was performed using the algorithms trained in models 1 and 2.

The steps and details of the proposed methodology are summarized in

Table 1. All models use ML for classification and feature analysis, differing only in the characteristics and composition of their outputs. It is worth noting that Models 1 and 2 include an additional step: applying the trained algorithms to classify customers who are categorized as neutrals by the NPS.

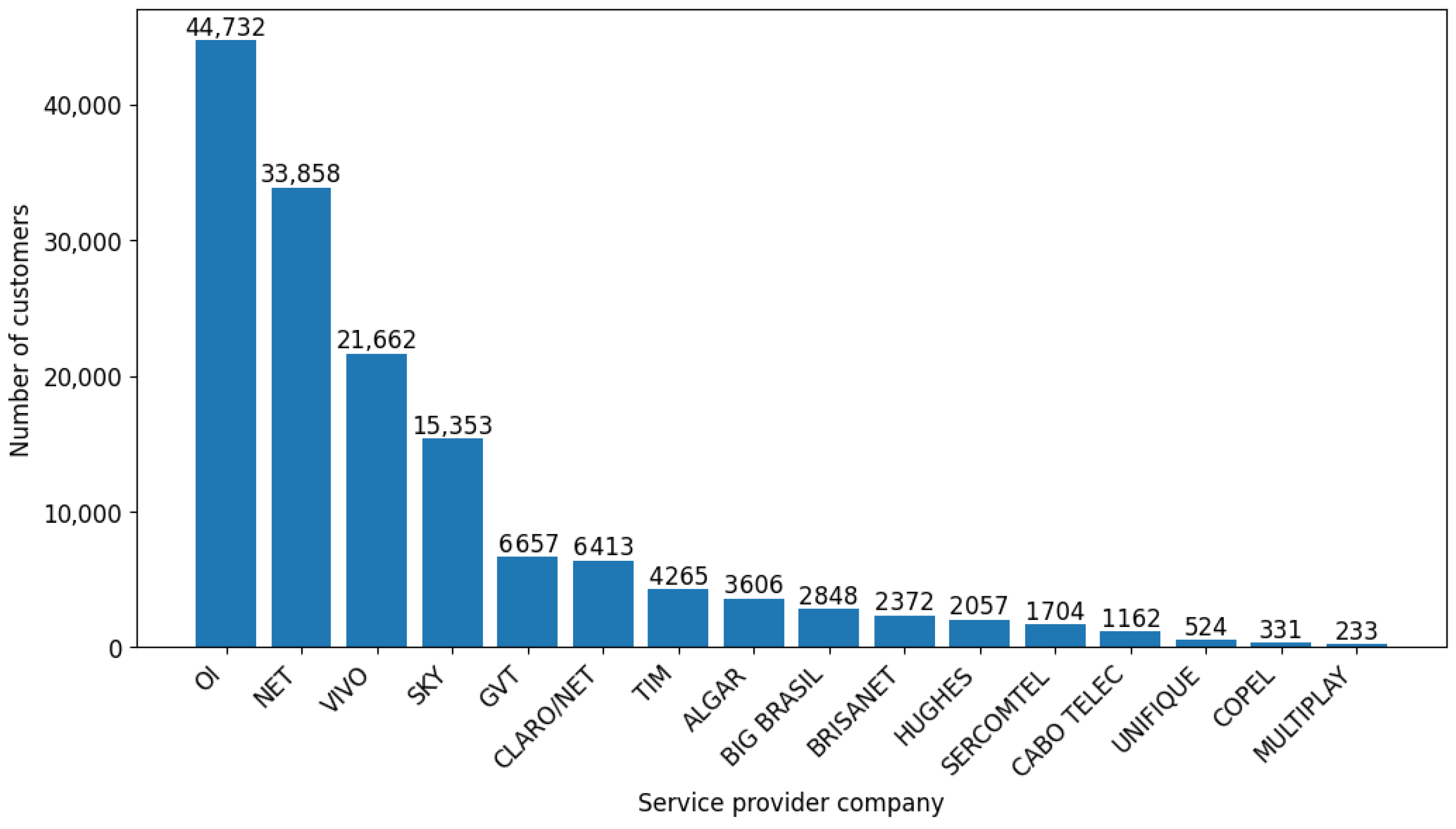

4.2. Dataset

The database was extracted from a customer satisfaction survey conducted by ANATEL (

https://github.com/mrelero/dados-pesquisa-matheus-elero-UEM, accessed on 23 February 2023), which was carried out annually between 2015 and 2020 and targeted broadband service users [

82]. For detailed information on the database composition, ANATEL provides a glossary with descriptions, field types, and the survey flow [

46].

The dataset, covering the period from 2015 to 2020, comprises 147,777 responses, with 63 variables corresponding to the survey questions.

Table 2 presents the types of questions and responses in the ANATEL questionnaire. The 63 columns in the database consist of four data types, with the “open-ended” and “selection” variables containing both text and numbers. For binary responses, the value can take two values: “1” for “yes” and “2” for “no.” Lastly, the Likert scale ranges from 0 to 10, indicating the level of satisfaction with a specific feature.

4.3. Data Preparation

The investigated database allows for various configurations and manipulations. As the dataset contains conditional questions, covers 5 years, has nationwide coverage, and comprises 147,777 rows, it can be used to generate other databases for ML applications. For this research, initial data preparation was conducted, and then the data were used to create three models based on the output column “J1” and the NPS indicator.

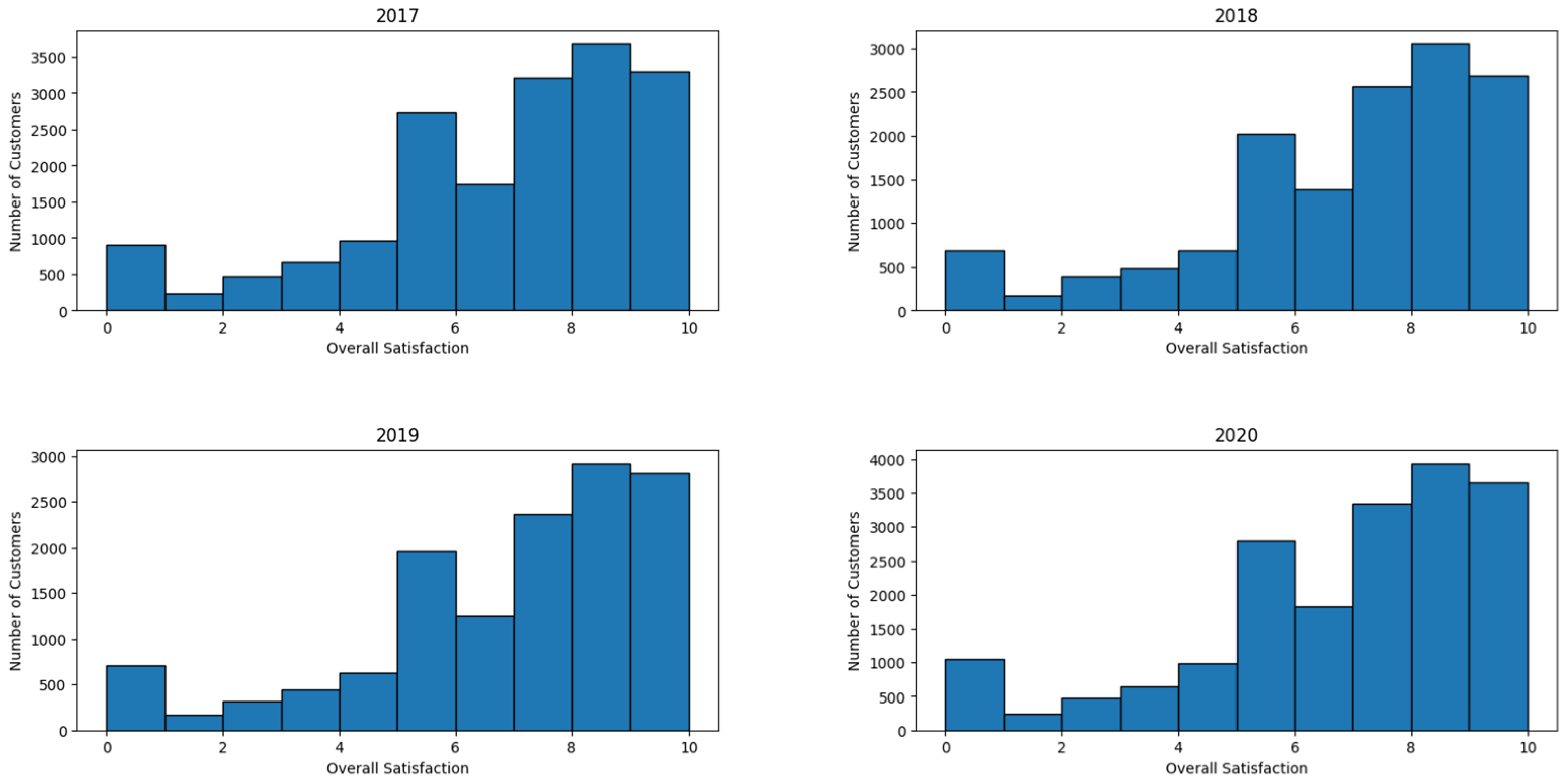

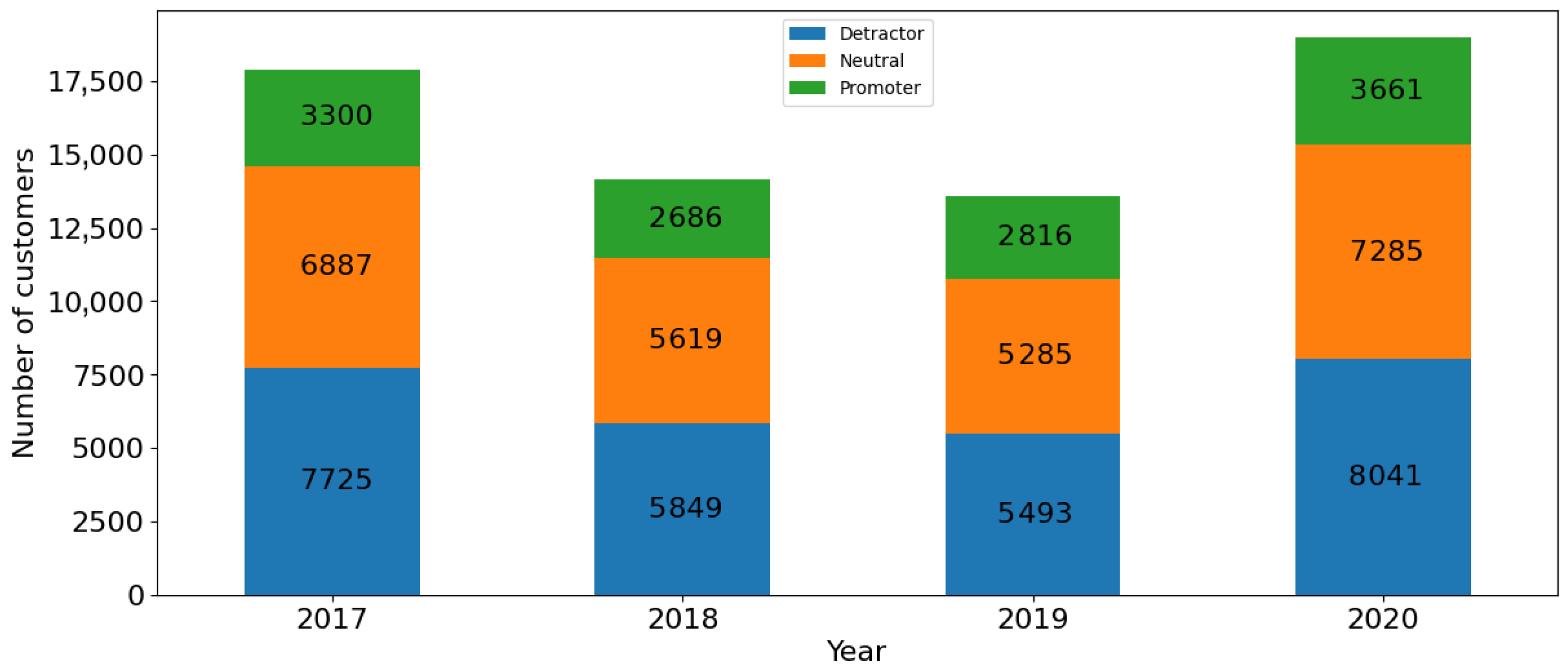

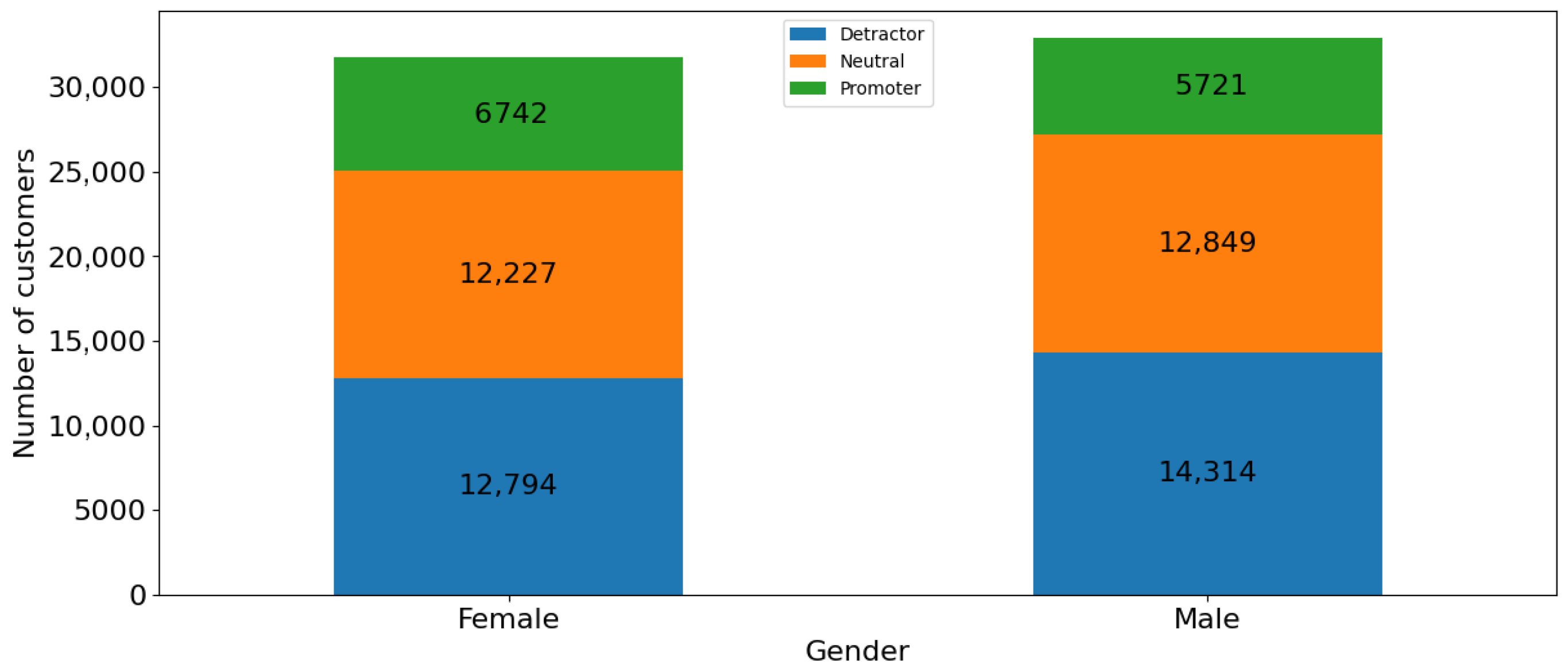

Table 3 presents the three steps carried out for data preparation. The first preparation consisted of identifying the subset used, removing columns and rows with empty cells, and responses that customers did not know how to answer. The period covered was 2017 to 2020, during which the questionnaire maintained the same structure each year. There were no restrictions based on age, state, income, gender, or the number of people using the broadband service. After this step, the database was reduced from 147,777 rows to 91,935 rows.

To expand the proportion used from the dataset, columns in which customers responded “yes” or “no” to specific subjects, such as E2, E4, E6, and E8, were considered, and the questions conditioned on these responses were consequently removed. Therefore, the following columns were removed: A2_1, A2_2, A2_3, A1_4, A3, A4, E2, E4, E6, E8, F2_1, F2_2, F2_3, F4_1, F4_2, and F4_3. Other columns with repeated, irrelevant, generalized, or sparse data were also removed: Q2, Q2_1, Q2_2, Q3, Q4, Q7a, IDTNS, G1, G2_1, G2_2, G2_3, PESO, Q1, Q6, H3, COD_IBGE, H2a, I2, and H0. As the objective of the project was to explore the most important features influencing service satisfaction, demographic data were excluded. After this processing, the database was reduced from 63 columns to 25.

Columns referring to optional response variables have been removed. Lines containing empty values or in which the respondent did not know how to answer the question were also removed. Finally, columns with string and categorical values were converted to numerical values, and columns with empty or filled “yes” or “no” responses were converted to binary values (0 or 1), where 0 represents “No” and 1 represents “Yes”. The resulting dataset had 64,647 rows and 25 columns, with column “J1” representing the overall satisfaction level, which served as a reference for constructing the three models.

Table 4 presents the class distribution for each generated model. The results show that few customers are considered promoters, indicating that the balance in Model 3 is only 19%. The outcome indicates that models 1 and 2 have a predominance of dissatisfied customers, with 60% in the first and 69% in the second.

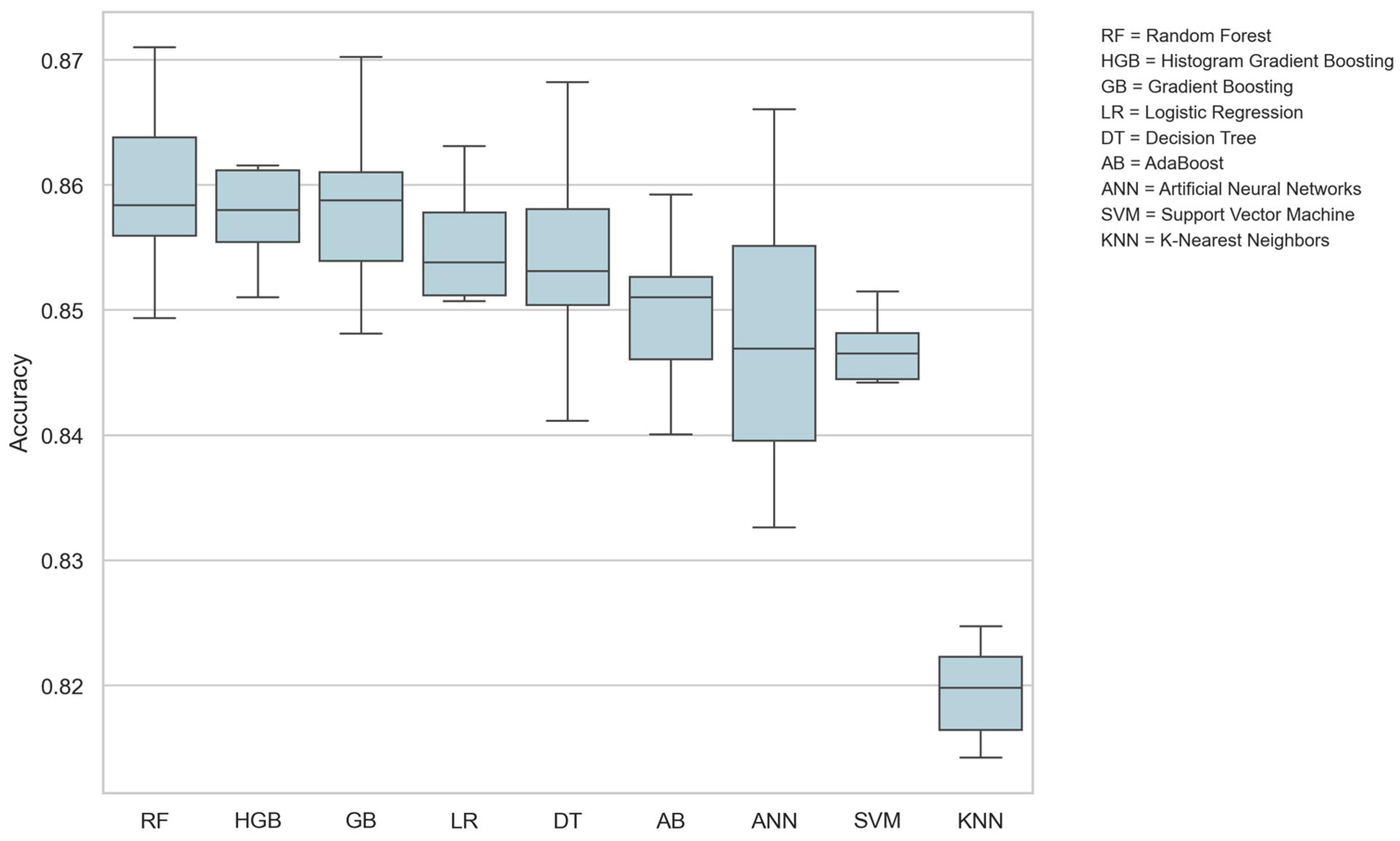

4.4. Application of ML Techniques

The application of ML in the three models was carried out using the scikit-learn and SciKeras libraries (

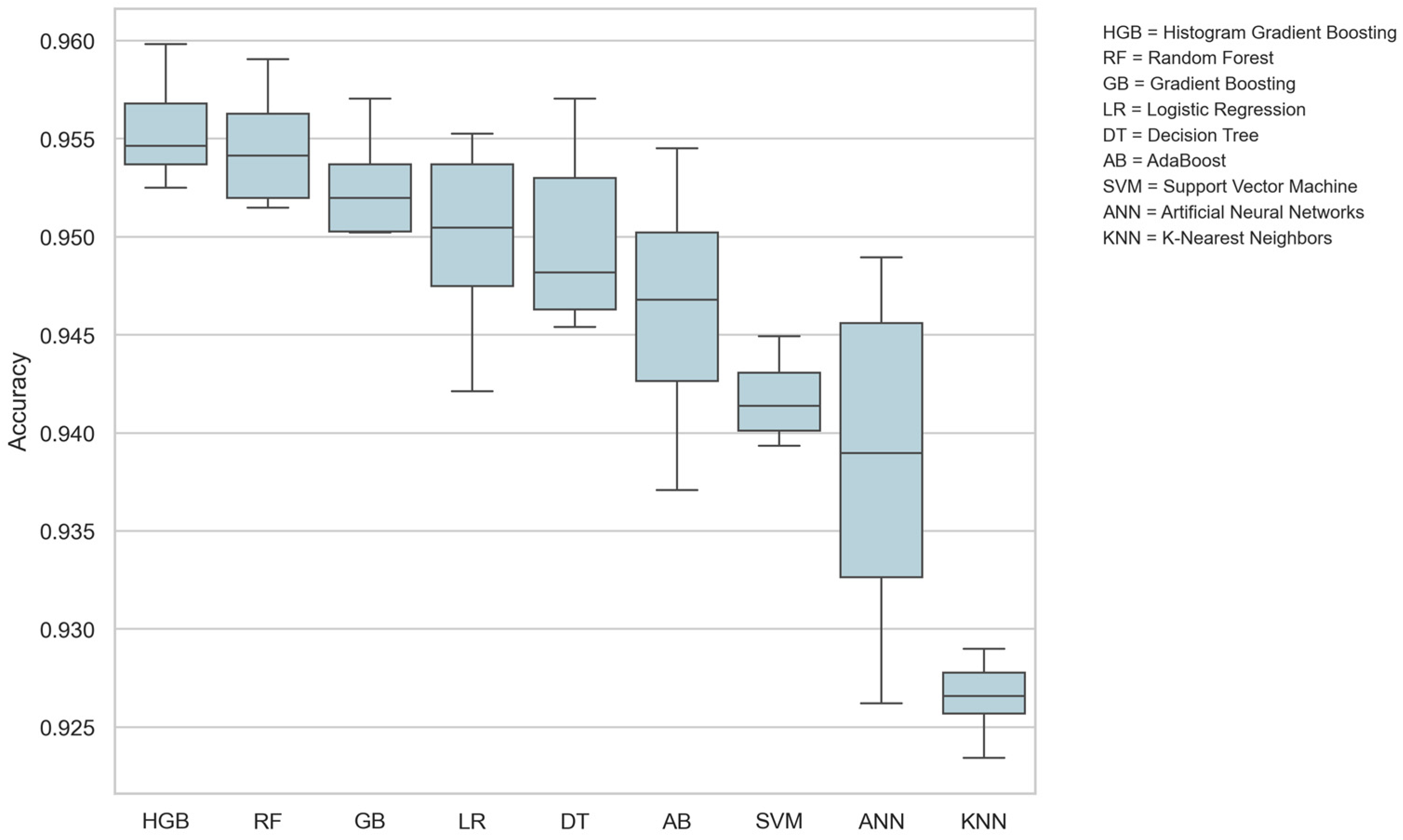

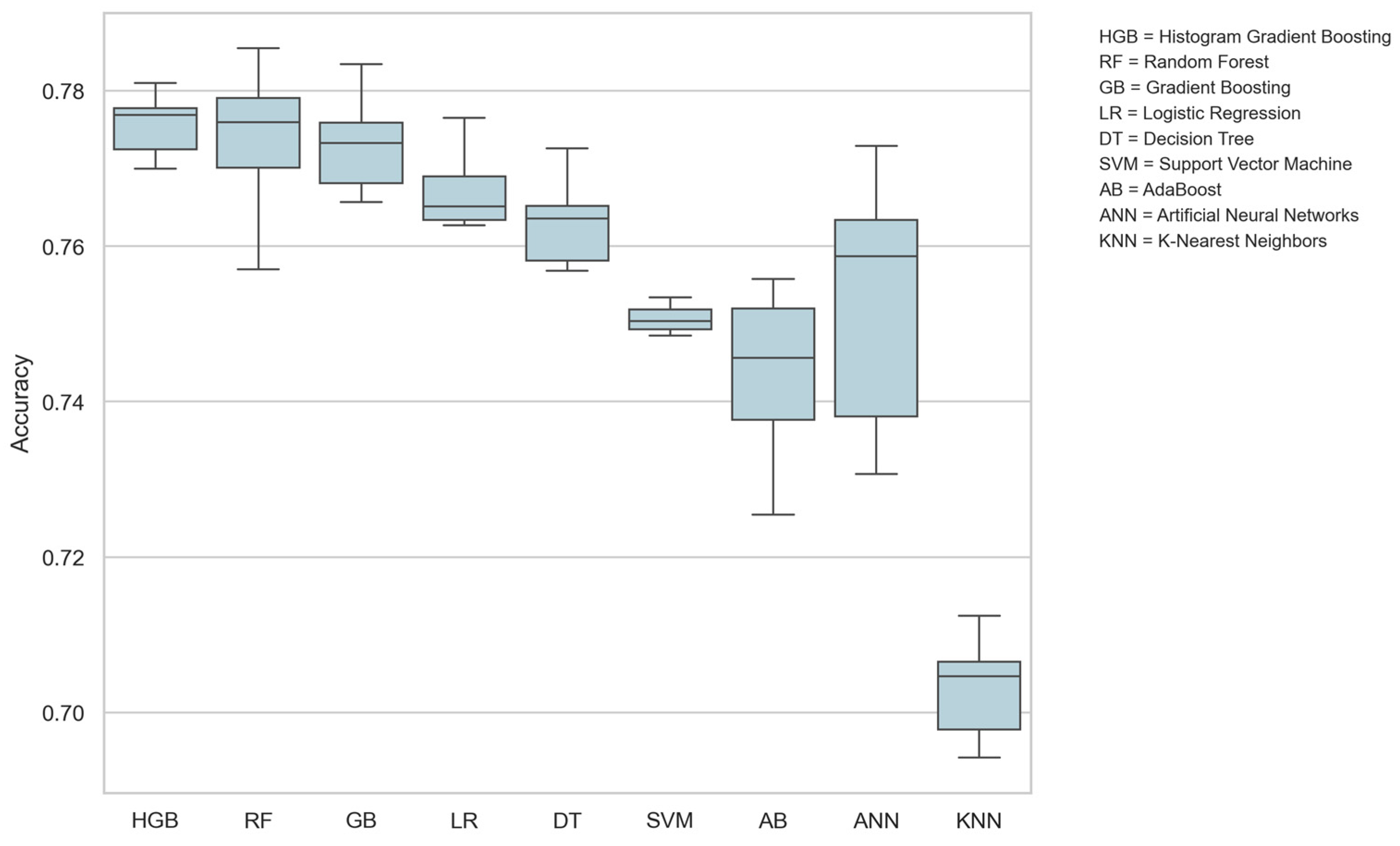

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/, accessed on 13 February 2023). First, the models to be applied were selected, and then a hyperparameter tuning was conducted using the Grid Search method. With the selection of optimal parameters, nine algorithms were trained, tested, and analyzed using accuracy, precision, F1 score, recall, AUC (Area Under the Curve), and k-fold cross-validation. All 25 variables were used directly in the training set without normalization.

Table 5 presents all the techniques and the parameter values chosen for the Grid Search. This method searches for the best parameter combination using cross-validation [

31]. All values were determined through individual tests of the techniques, with execution time and performance considered. The Grid Search method was applied using 5-fold cross-validation. The resulting parameters were selected to train and test all techniques. Finally, an additional test was performed using 10-fold cross-validation across all techniques, with accuracy as the evaluation metric. Results were visualized using box plots.

Table 6 presents the techniques and best resulting parameters from the Grid Search process. Considering the three models, it is possible to identify that in some techniques, such as SVM, RL, and AB, there was little variation in the chosen parameters, resulting in the same parameter composition across all three models. Since Grid Search can be time-consuming, the joblib library was used to save the trained models with the configured hyperparameters, preventing loss of development progress. A pseudocode is presented in

Appendix A.

4.5. Feature Importance

Two approaches were used to find which factors matter most for broadband customer satisfaction in Brazil. The first method is to assess the importance of each feature using three computer models: RF, DT, and AB. These models measure how much each feature helps make better predictions during training. The process was done for all three models, and their results were compared.

In contrast to the first approach, the second one involved applying the SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) analysis using the Python SHAP library, version 0.41 [

83]. As presented by Lundberg and Lee [

84], SHAP assigns an importance value to each feature for a given prediction. For this research, the RF technique was selected for SHAP application due to its strong performance relative to others, and the Tree Explainer method introduced by Lundberg et al. [

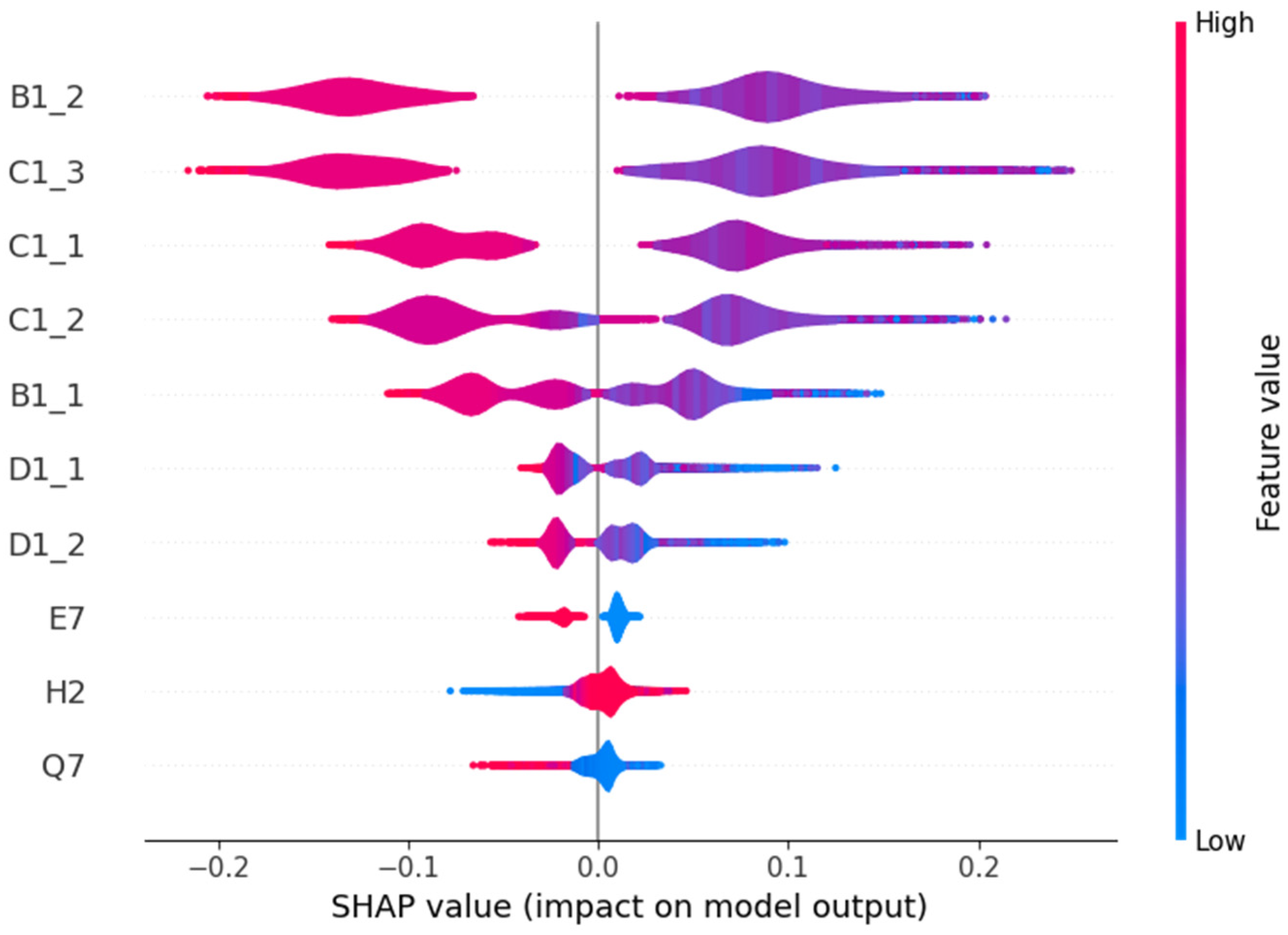

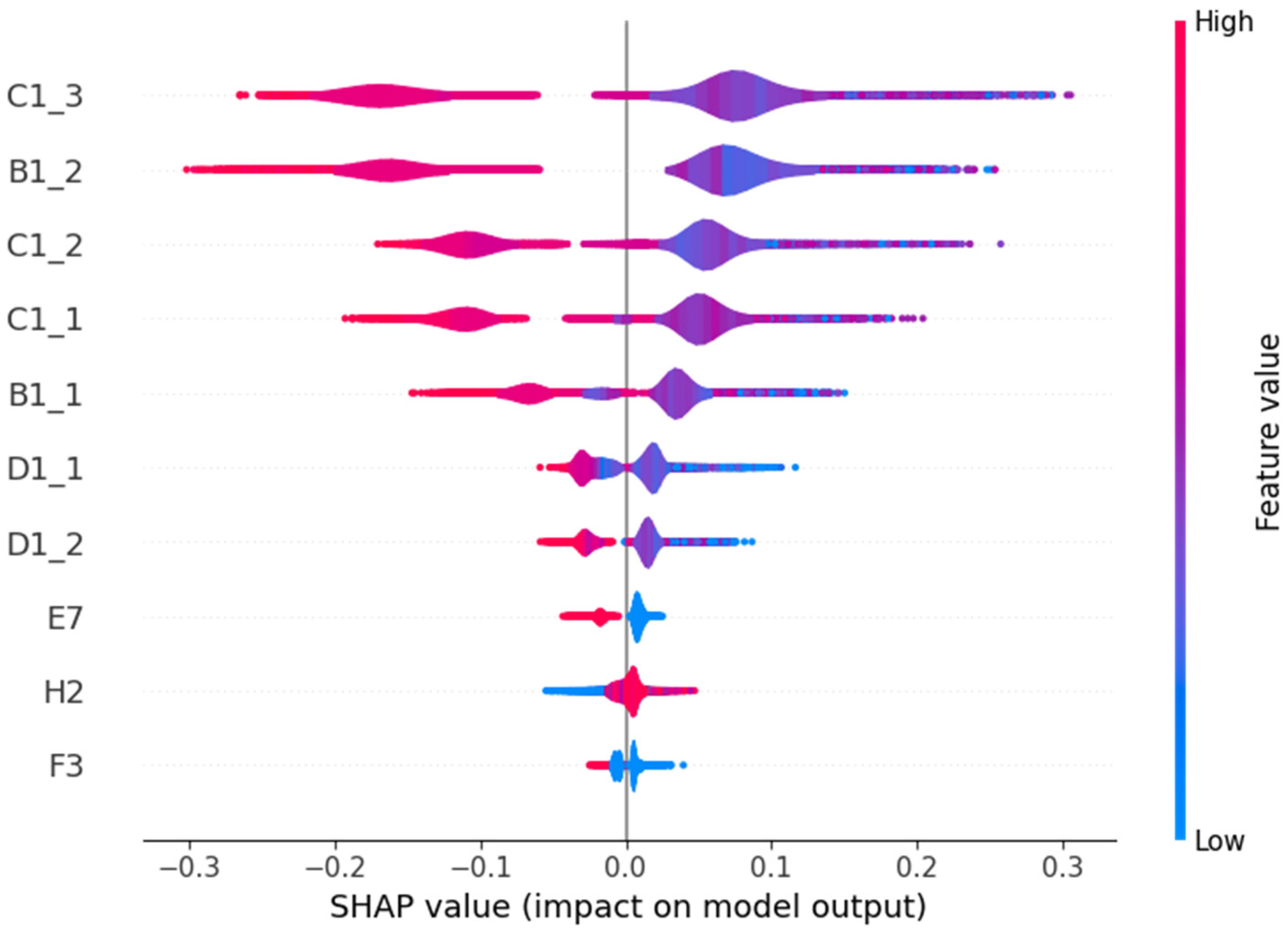

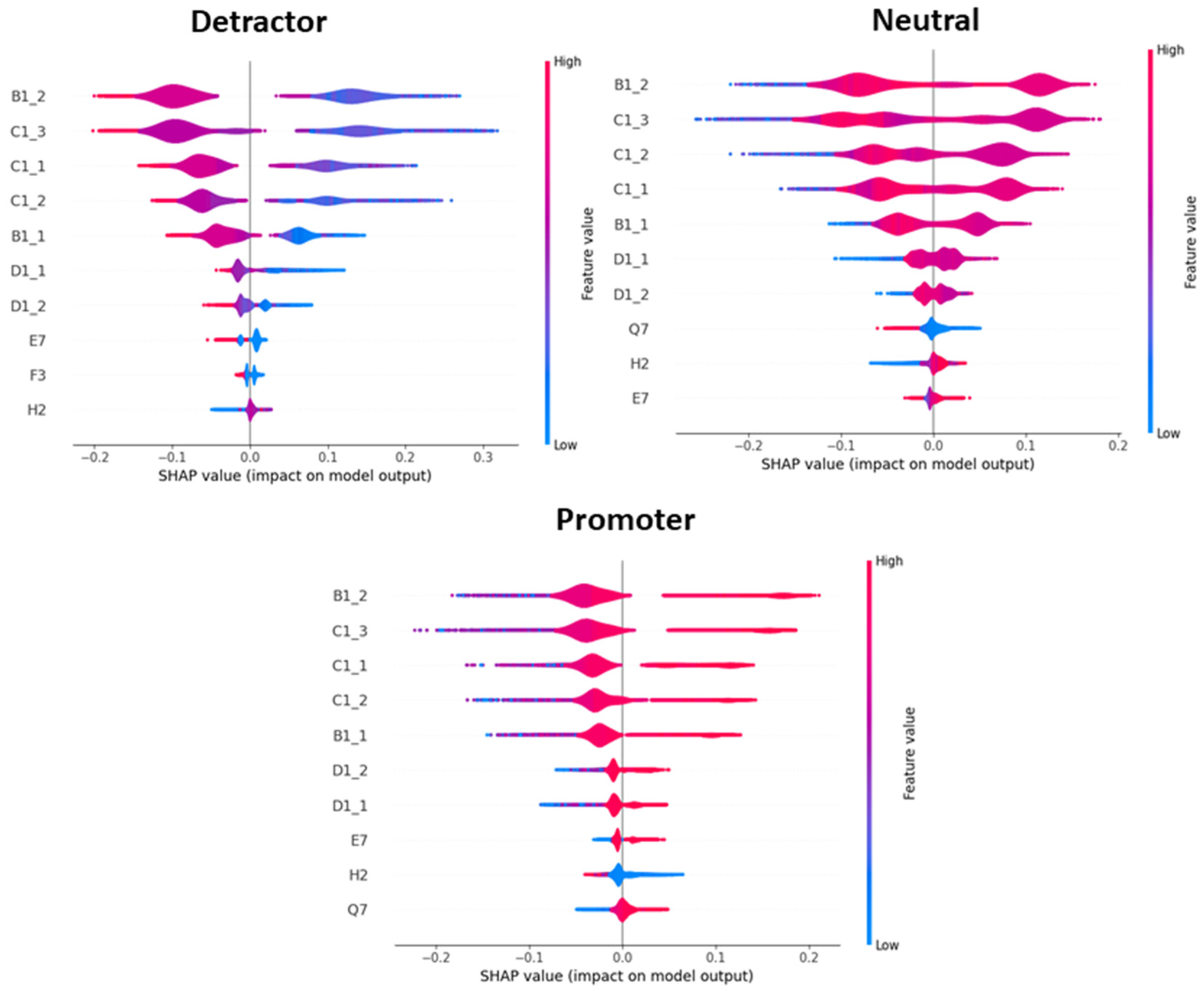

85] was used in conjunction with the test set. The results were analyzed through bar charts and beeswarm plots for all three models.

4.6. Neutral Customers Analysis

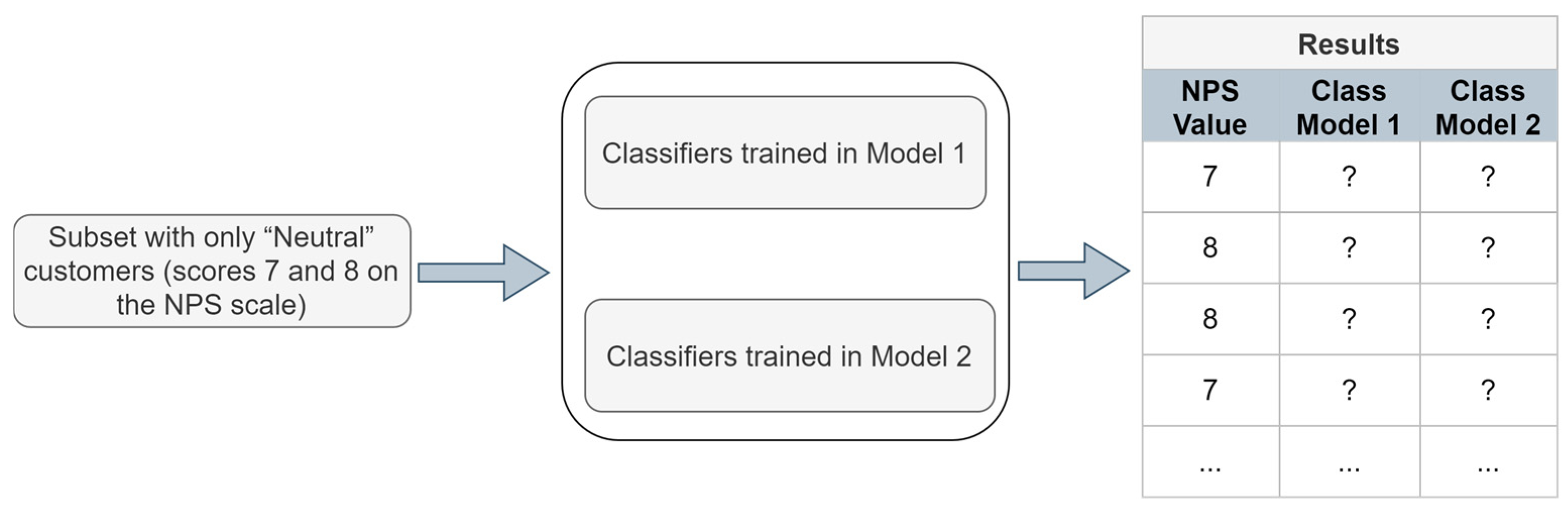

Model 2 uses a dataset with customers who rated their satisfaction as “7” or “8” removed from the training set. Here, ML techniques are trained only on the extremes: customers who rate 9 or higher are satisfied, and those who rate 6 or lower are dissatisfied. This format mirrors NPS classification and excludes neutral customers.

Figure 3 presents a flowchart of the neutral analysis. For the Model 2 techniques, data from customers who rated their satisfaction as “7” and “8” were removed and used as input to the classifiers after training. This allowed classification according to the trained criteria. Model 1 classifiers also classified these neutral customers. The results were analyzed by calculating the percentages of satisfied and dissatisfied classifications, determined by ratings of “7” or “8.” Heatmaps and cross-tabulation aided the analysis.

Neutral customers represent indecision regarding their satisfaction with the services provided. Therefore, it is necessary to determine whether such customers exhibit more characteristics of satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Model 1 and Model 2 were trained with different labeling strategies, so their application to classify neutral customers aims to better understand the characteristics of these instances by comparing the results.

6. Discussion

In general, supervised ML techniques were applied to classify customers based on their satisfaction, using data from the ANATEL customer satisfaction survey. The Net Promoter Score (NPS), commonly used by service providers to categorize customers as detractors, neutrals, and promoters, was used as the basis for the classification.

Based on the “Overall Satisfaction with Service” output variable, three models were built with different thresholds to segment customers according to NPS benchmarks. Model 1 used binary classification, with satisfied customers defined as those who rated the service “8” or higher, and dissatisfied customers as those who rated below “8.” Model 2 removed customers who rated “7” or “8”; here, satisfied customers had ratings of “9” or above, while dissatisfied customers had ratings of “6” or below. Model 3 used multiclass classification based on the NPS classes: Detractors, Neutrals, and Promoters. For all models presented in the

Section 5, preliminary analyses were conducted to assess the risk of overfitting. No discrepancies were observed between the results on the training and test datasets.

Table 14 summarizes the most relevant features and their positions based on the rankings in

Table 9,

Table 11 and

Table 13, generated using the ML techniques RF, DT, and GB, as well as the SHAP method. The top five features in all methods were: rating of the operator’s commitment to fulfill promises (B1_2), navigation speed (C1_3), billing accuracy with the contracted plan (C1_1), ability to maintain connection without drops (C1_2), and ease of understanding plans and services (B1_1). For RF, DT, and GB, C1_3, B1_2, and C1_1 showed the highest importance scores.

The SHAP results also indicated that features B1_2, C1_3, and C1_1 had higher average absolute impact values on the output. The SHAP values also enabled a more detailed identification of each feature’s impact. In all cases, the importance of the features remained the same, with only changes in their positions. This result shows alignment with the findings from other methods.

The findings from

Table 14 align with related work by Abdullah et al. [

79], who found that network quality and connectivity were among the main drivers of satisfaction in the telecommunications industry. In our results, browsing speed and connection stability had a strong impact on customer satisfaction classification. These aspects directly impact the customer experience and are related to service reliability, as connection failures and low speeds can disrupt customers’ communications and daily activities.

Other factors identified as relevant in

Table 14, such as billing accuracy, fulfillment of contract clauses as advertised, and ease of understanding the contracted plans, can be viewed as the gap between what the customer expected when hiring the services and the perceived quality after the services were provided. This is supported by Suchanek and Bucicova [

78], who detected a negative relationship between customer expectations and perceived service value. This finding indicates that companies should align their marketing and communication efforts with the services they actually provide. Customers seem concerned about billing and contract transparency to avoid unexpected charges.

Regarding Brazil, the most important features are browsing speed, the delivery of the advertised service, and connection stability, which are key drivers of customer satisfaction. These findings are consistent with results reported by the Institute for Applied Economics [

87], which showed that download rates, their reference values (contracted download speed), and customer satisfaction are closely related. This evidence suggests that, for most Brazilian consumers, the alignment between what is paid for at the time of contracting and what is actually delivered is critical, reinforcing the need for service providers to deliver what is contractually promised. Moreover, ANATEL requires that the average broadband internet speed delivered to consumers be at least 80% of the contracted speed and not fall below 40% at any time during usage. If these conditions are not met, consumers may file a complaint with the competent authority to enforce their rights and, as a last resort, pursue legal action against the service provider.

The research conducted by Markoulidakis et al. [

77] also explored ML using NPS, but they used data from postpaid mobile telecom customers in Greece. The authors identified several important features for classification using SHAP values in a linear regression model. The authors highlighted four features: “Network Voice,” which indicates the network quality for voice services; “Tariff Plan,” the billing plan used; “Billing,” the billing process; and “Network Data,” the data network quality. Despite the companies offering different services within the same industry, it is possible to draw some connections. Their results indicated that the most important features are related to billing and network quality, which aligns with the findings presented in this article, showing that some of the most relevant features are also related to payment and connection quality.

Another study that analyzed the most relevant features was conducted by Hosseini and Ziaei Bideh [

47], which applied a satisfaction questionnaire to mobile telecom customers in Yazd province, Iran. The authors identified the most relevant features for satisfaction as value-added services, customer support, network quality, and plan prices. Similar to the findings by Markoulidakis et al. [

77], their publication also indicated features related to payment and network quality.

Indeed, despite differences in terminology, the services provided, and the methodology used to calculate the features, this research aligns with the studies by Markoulidakis et al. [

77] and Hosseini and Ziaei Bideh [

47]. This study identified the five most important features for classification, among which one is related to billing (ratings assigned to billing based on the contract), and two are related to network quality, such as ratings for browsing speed and the ability to maintain a stable connection. Therefore, the most relevant features identified in this study indicate a connection to two research works in the literature.

7. Conclusions

Since 2016, there has been a significant growth in publications on the use of ML in service quality management. The available literature varies across various aspects, including scientific objectives, sectors, databases, methods, types of learning, and techniques. Given that the telecommunications sector still has few publications in the international literature and none in the Brazilian literature, this research aimed to apply ML techniques to analyze satisfaction data on telecommunications services in Brazil.

Beyond analyzing classifier performance metrics and XAI-based models for a deeper understanding of the underlying features, this study has both theoretical and practical implications. From a theoretical perspective, the findings demonstrate that the Net Promoter Score (NPS) can be integrated as a variable of interest in applications involving nonlinear ML-based models. Moreover, the XAI-based models identified several relevant variables that can be assessed or prioritized in any context involving broadband internet services, serving as references for customer satisfaction and loyalty strategies, as well as for marketing direction regarding product and service delivery.

From a practical standpoint, the results indicate that “browsing speed” and “billing” are priority variables in planning and managing critical factors to increase the likelihood of customer satisfaction and potential loyalty while simultaneously reducing the probability of churn. To this end, infrastructure stability and transparency in billing processes are essential. In addition, the nationwide survey conducted by ANATEL provides frequent, quantitative evidence to support shifts in broadband users’ priorities, serving as a reference for management practices, public policy formulation, and updates to regulations governing the provision of this service.

Therefore, the results presented in this article also reveal challenges in applying ML techniques to classify customer satisfaction. As a study limitation, the dataset’s use of a 10-point Likert scale as the output introduces uncertainty when transforming it into discrete classes, given the diversity of customer choices, intermediate levels, and neutral satisfaction states. Additionally, there are ongoing debates about the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty, with no definitive evidence of causality. This study used NPS-based classification as a reference to facilitate the interpretation of classification algorithms; however, no in-depth analysis of this categorization was conducted. It is also worth noting that the data used (2017–2020) were selected based on availability at the beginning of the research, characterizing the study as retrospective. While more recent data were not analyzed, the proposed methodology can be extended to contemporary datasets.

Subsequent research could investigate additional classification techniques not explored in this study, as well as further preprocessing strategies such as linearization, data imputation, and class balancing. Regarding XAI-based interpretations, the use of alternative techniques, such as Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME), DeepSHAP, and Accelerated Model-Agnostic Explanations (ACME), would be valuable to complement analyses of feature importance across models. Furthermore, the methodology may be replicated using more recent data to compare the impact of predictor variables across NPS categories and observe changes in their importance for detractors and promoters. Finally, qualitative studies derived from this research could explore the telecommunications market more broadly, addressing service levels, oligopolistic structures, and emerging trends in customer requirements.