The Cognitive Affective Model of Motion Capture Training: A Theoretical Framework for Enhancing Embodied Learning and Creative Skill Development in Computer Animation Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

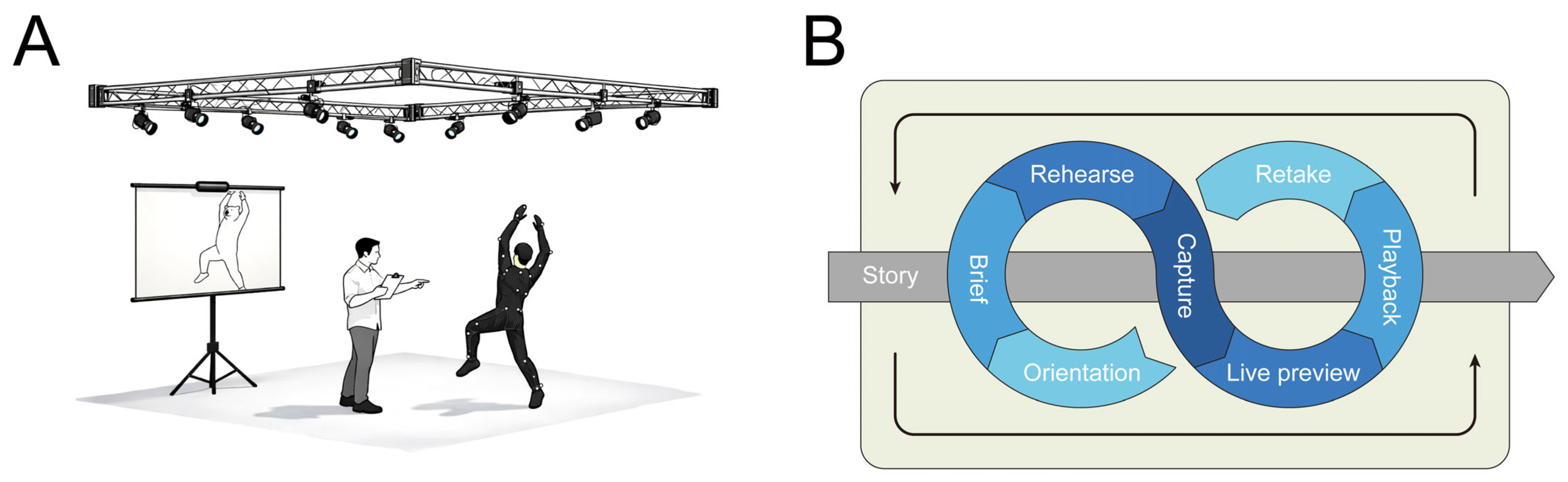

2. Defining MoCap in Computer Animation Design and Training

3. The Theoretical Perspective of CAMMT

3.1. What Factors Lead to Presence in CAMMT?

3.2. What Factors Lead to Agency in CAMMT?

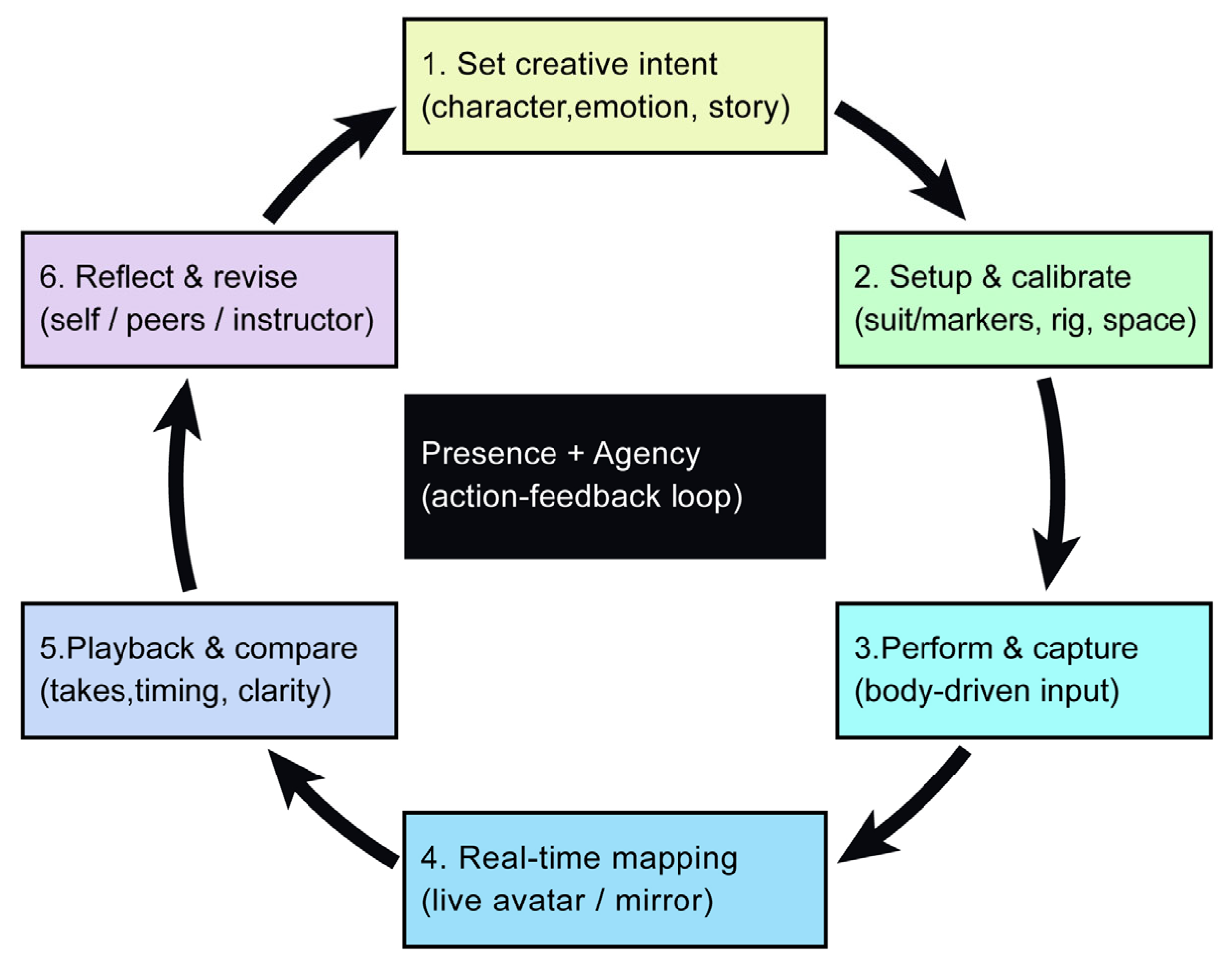

3.3. How Presence and Agency Mediate CAMMT’s Six Constructs in Fostering Embodied Creativity and Design Innovation?

3.3.1. Control and Active Learning

3.3.2. Reflective Thinking

3.3.3. Perceptual Motor Skills

3.3.4. Emotional Expressive

3.3.5. Artistic Innovation

3.3.6. Collaborative Construction

3.4. Validation and Verification of CAMMT

3.4.1. Operationalization Roadmap for Classroom V&V

3.4.2. Suggested Empirical Designs for Testing CAMMT

3.5. Case Illustration: Applying CAMMT in a Character Performance Module

4. What Are the Creative and Cognitive Outcomes Included in the CAMMT?

5. What Are the Implications for Future Research Based on CAMMT?

6. Important External Factors That Influence the CAMMT

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| CAMIL | Cognitive Affective Model of Immersive Learning |

| CAMMT | Cognitive Affective Model of Motion Capture Training |

| CATLM | Cognitive Affective Theory of Learning with Media |

| HCI | Human–Computer Interaction |

| IVR | Immersive Virtual Reality |

| MoCap | Motion Capture |

| MR | Mixed Reality |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

References

- Hart, H. When Will a Motion-Capture Actor Win an Oscar? WIRED. 24 January 2012. Available online: https://www.wired.com/2012/01/andy-serkis-oscars/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Wibowo, M.C.; Nugroho, S.; Wibowo, A. The use of motion capture technology in 3D animation. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2024, 15, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, A.S.; Schindler, M. Motion capture systems and their use in educational research: Insights from a systematic literature review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, G.; Kruse, J. Teaching visual storytelling for virtual production pipelines incorporating motion capture and visual effects. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2015 Symposium on Education, Kobe, Japan, 2–6 November 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, T.Y. Motion capture in supporting creative animation design. In DS86, Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Design Creativity, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2–4 November 2016; The Design Society: Shenzhen, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, H.; Kennedy, J.; Ramsay, E.; Todoroki, M.; Bennett, G. A pedagogical workflow for interconnected learning: Integrating motion capture in animation, visual effects, and game design: Major/minor curriculum structure that supports the integration of motion capture with animation, visual effects and game design teaching pathways. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2024 Educator’s Forum (SA ’24). Association for Computing Machinery, Tokyo, Japan, 3–6 December 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makransky, G.; Petersen, G.B. The cognitive affective model of immersive learning (CAMIL): A theoretical research-based model of learning in immersive virtual reality. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 937–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, B. Andy Serkis: Why Won’t Oscars Go Ape over Motion-Capture Acting. The Guardian, 12 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp, I. Motion Capture Actors: Body Movement Tells the Story. DirectSubmit from NYCastings. 2017. Available online: https://www.nycastings.com/motion-capture-actors-body-movement-tells-the-story (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Salomon, A. Growth in Performance Capture Helping Gaming Actors Weather Slump; Backstage: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.backstage.com/magazine/article/growth-performance-capturehelping-gaming-actors-weatherslump-47881/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Auslander, P. Film acting and performance capture. PAJ J. Perform. Art 2017, 39, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menolotto, M.; Komaris, D.-S.; Tedesco, S.; O’Flynn, B.; Walsh, M. Motion capture technology in industrial applications: A systematic review. Sensors 2020, 20, 5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, T.-Y. Keyframe or motion capture? Reflections on education of character animation. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2018, 14, em1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, N. Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dorst, K. Design problems and design paradoxes. Des. Issues 2006, 22, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.M.; Blascovich, J.J.; Beall, A.C. Immersive virtual environment technology as a basic research tool in psychology. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1999, 31, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.; Sanchez-Vives, M.V. Enhancing our lives with immersive virtual reality. Front. Robot. AI 2016, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, M.C.; Dede, C.; Loftin, R.B.; Chen, J. A model for understanding how virtual reality aids complex conceptual learning. Presence Teleoper. Virtual Environ. 1999, 8, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.A.-L.; Wong, K.W.; Fung, C.C. How does desktop virtual reality enhance learning outcomes? A structural equation modeling approach. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 1424–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makransky, G.; Lilleholt, L. A structural equation modeling investigation of the emotional value of immersive virtual reality in education. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2018, 66, 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, P. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makransky, G.; Petersen, G.B. Investigating the process of learning with desktop virtual reality: A structural equation modeling approach. Comput. Educ. 2019, 134, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R.; Mayer, R. Interactive multimodal learning environments: Special issue on interactive learning environments: Contemporary issues and trends. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 19, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gero, J.S. Design prototypes: A knowledge representation schema for design. AI Mag. 1990, 11, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M.A.; Jaeger, G.J. The standard definition of creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2012, 24, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, V. Sketches of Thought; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt, G. Linkography: Unfolding the Design Process; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guilford, J.P. The Nature of Human Intelligence; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Torrance, E.P. Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking: Norms-Technical Manual; Scholastic Testing Service: Bensenville, IL, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.M. Presence, explicated. Commun. Theory 2004, 14, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G.; Davide, F.; IJsselsteijn, W.A. Being There: Concepts, Effects and Measurements of User Presence in Synthetic Environments; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Witmer, B.G.; Singer, M.J. Measuring presence in virtual environments: A presence questionnaire. Presence 1998, 7, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgarno, B.; Lee, M.J. What are the learning affordances of 3-D virtual environments? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2010, 41, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavò, A.; Pratticò, F.G.; Bruno, A.; Lamberti, F. AR-MoCap: Using augmented reality to support motion capture acting. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Shanghai, China, 25–29 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour, M. Art of LED Wall Virtual Production, Part One: Lessons from the Mandalorian. 2022. Available online: https://www.luxmc.com/press-a/art-of-led-wall-virtual-production-part-one-lessons-from-the-mandalorian/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Moore, J.W.; Fletcher, P.C. Sense of agency in health and disease: A review of cue integration approaches. Conscious. Cogn. 2012, 21, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Glenberg, M.C. The necessary nine: Design principles for embodied VR and active STEM education. In Learning in a Digital World: Perspectives on Interactive Technologies for Formal and Informal Educationi; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 83–112. [Google Scholar]

- Farrer, C.; Bouchereau, M.; Jeannerod, M.; Franck, N. Effect of distorted visual feedback on the sense of agency. Behav. Neurol. 2008, 19, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilteni, K.; Groten, R.; Slater, M. The sense of embodiment in virtual reality. Presence Teleoper. Virtual Environ. 2012, 21, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, J.W. Improving Student Understanding with TEAL; The MIT Faculty Newsletters: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Mitchell, K. Group-based expert walkthroughs: How immersive technologies can facilitate the collaborative authoring of character animation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), Atlanta, GA, USA, 22–26 March 2020; pp. 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomão, A.; Andaló, F.; Prim, G.; Horn Vieira, M.L.; Romeiro, N.C. Case studies of motion capture as a tool for human-computer interaction research in the areas of design and animation. In Human-Computer Interaction. Theoretical Approaches and Design Methods; Kurosu, M., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Cho, Y.; Na, G.; Kim, J. Application of virtual avatar using motion capture in immersive virtual environment. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 6344–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraffi, T. Metahuman theatre: Teaching photogrammetry and MoCap as a performing arts process. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH 2024 Educator’s Forum, Denver, CO, USA, 27 July–1 August 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, G.B.; Petkakis, G.; Makransky, G. A study of how immersion and interactivity drive VR learning. Comput. Educ. 2022, 179, 104429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Glenberg, M.C.; Megowan-Romanowicz, C. Embodied science and mixed reality: How gesture and motion capture affect physics education. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2017, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process; D.C. Heath: Lexington, MA, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. The Theory of Communicative Action, Vol. 2: Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason; McCarthy, T., Translator; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper, R.A.; Pesut, D.J. Promoting cognitive and metacognitive reflective reasoning skills in nursing practice: Self-regulated learning theory. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 45, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcic, A.I.; Lipsmeyer, W.M.; Lin, L. Using motion capture technologies to provide advanced feedback and scaffolds for learning. In Mind, Brain and Technology: Learning in the Age of Emerging Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiiski, H.; Hoyet, L.; Woods, A.T.; O’Sullivan, C.; Newell, F.N. Strutting hero, sneaking villain: Utilizing body motion cues to predict the intentions of others. ACM Trans. Appl. Percept. 2015, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, C.; Fujita, H.; Perin, G. Towards a knowledge-based environment for the cognitive understanding and creation of immersive visualization of expressive human movement data. In Trends in Applied Knowledge-Based Systems and Data Science; Fujita, H., Ali, M., Selamat, A., Sasaki, J., Kurematsu, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J.L.; Wortham, S.C.; Reifel, R.S. Play and Child Development; Pearson: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, N.; Ayyub, M.; Sun, H.; Wen, X.; Xiang, P.; Gao, Z. Effects of physical activity on motor skills and cognitive development in early childhood: A systematic review. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 2760716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, E. Acting for Animators; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miaw, D.R.; Raskar, R. Second skin: Motion capture with actuated feedback for motor learning. In CHI ’09 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 4537–4542. [Google Scholar]

- Pilati, F.; Faccio, M.; Gamberi, M.; Regattieri, A. Learning manual assembly through real-time motion capture for operator training with augmented reality. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 45, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprenkels, B. Promoting Motor Learning in Squats Through Visual Error Augmented Feedback: A Markerless Motion Capture Approach. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Manaf, A.A.; Arshad, M.R.; Bahrin, K. Team learning in motion capture operations and independent rigging processes. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 2545–2549. [Google Scholar]

- Ståhl, A. Designing for Emotional Expressivity. Doctoral Dissertation, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, E.; Gross, M. Motion capture and emotion: Affect detection in whole body movement. In Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction; Paiva, A.C.R., Prada, R., Picard, R.W., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, C.; Hoyet, L.; Egges, A.; McDonnell, R. Emotion capture: Emotionally expressive characters for games. In MIG ’13 Proceedings of Motion on Games; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkielman, P.; Niedenthal, P.; Wielgosz, J.; Eelen, J.; Kavanagh, L.C. Embodiment of cognition and emotion. In APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, W. Evolution and innovations in animation: A comprehensive review and future directions. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2024, 36, e7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, R.A.; Ward, T.B.; Smith, S.M. Creative Cognition: Theory, Research, and Applications; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, T.B. Structured imagination: The role of category structure in exemplar generation. Cogn. Psychol. 1994, 27, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, M.A. The Creative Mind: Myths and Mechanisms; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J.C.; Leung, H.; Tang, J.K.; Komura, T. A virtual reality dance training system using motion capture technology. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2010, 4, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F.; Bruhn, J.; Gräsel, C.; Mandl, H. Fostering collaborative knowledge construction with visualization tools. Learn. Instr. 2002, 12, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asllani, A.; Ettkin, L.P.; Somasundar, A. Sharing knowledge with conversational technologies: Web logs versus discussion boards. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2008, 7, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cila, N. Designing human-agent collaborations: Commitment, responsiveness, and support. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 30 April–5 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chheang, V.; Saalfeld, P.; Joeres, F.; Boedecker, C.; Huber, T.; Huettl, F.; Lang, H.; Preim, B.; Hansen, C. A collaborative virtual reality environment for liver surgery planning. Comput. Graph. 2021, 99, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, U.; Na, E.J.; Jeon, H.J. A literature overview of virtual reality (VR) in treatment of psychiatric disorders: Recent advances and limitations. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Helal, S.; De Deugd, S.; Smith, A.; Chang, C.K. Toward a collaboration model for smart spaces. In Proceedings of the 2012 Third International Workshop on Software Engineering for Sensor Network Applications (SESENA), Zurich, Switzerland, 2 June 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devigne, L.; Babel, M.; Nouviale, F.; Narayanan, V.K.; Pasteau, F.; Gallien, P. Design of an immersive simulator for assisted power wheelchair driving. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics (ICORR), London, UK, 17–20 July 2017; pp. 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Glenberg, M.C.; Birchfield, D.A.; Tolentino, L.; Koziupa, T. Collaborative embodied learning in mixed reality motion-capture environments: Two science studies. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, L.; Lu, J.; Du, L.; Shen, G. A preliminary study on collaborative methods in animation design. In Proceedings of the 2010 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design, Shanghai, China, 14–16 April 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti, F.; Paravati, G.; Gatteschi, V.; Cannavo, A.; Montuschi, P. Virtual character animation based on affordable motion capture and reconfigurable tangible interfaces. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2017, 24, 1742–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parong, J.; Mayer, R.E. Learning science in immersive virtual reality. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 110, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Agrawala, M.; Curless, B.; Cohen, M. MotionMontage: A system to annotate and combine motion takes for 3D animations. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G.W.; Dinan, G.; Smolic, A. Realtime-3D interactive content creation for multi-platform distribution: A 3D interactive content creation user study. In Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality, Proceedings of the 15th International Conference, VAMR 2023, Held as Part of the 25th HCI International Conference, HCII 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark, 23–28 July 2023, Proceedings; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megre, R.; Kunz, S. Motion capture visualisation for mixed animation techniques. In Proceedings of the Electronic Visualisation and the Arts London 2020 Conference, London, UK, 16–20 November 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, J.; Blosch, M. Understanding Gartner’s Hype Cycles; Gartner: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, G.; Denton, A. Developing practical models for teaching motion capture. In ACM SIGGRAPH ASIA 2009 Educators Program; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolai, J.R.; Bennett, G.; Marks, S.; Gilson, G. Active learning and teaching through digital technology and live performance: ‘Choreographic thinking’ as art practice in the tertiary sector. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2019, 38, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunleavy, M.; Dede, C.; Mitchell, R. Affordances and limitations of immersive participatory augmented reality simulations for teaching and learning. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2009, 18, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, A.; Prophet, J. The state of immersive technology research: A literature analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Legault, J.; Klippel, A.; Zhao, J. Virtual reality for student learning: Understanding individual differences. Hum. Behav. Brain 2020, 1, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, Q.; Ma, D. User experience of a serious game for physical rehabilitation using wearable motion capture technology. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 108407–108417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | CAMIL | CAMMT |

|---|---|---|

| Primary focus | Learning in immersive virtual reality (IVR): how VR features shape presence/agency and learning outcomes. | MoCap-based character animation training: how performance affordances shape presence/agency and creative skill development. |

| Core interaction locus | Learner is situated in a simulated virtual environment and interacts with virtual content (often HMD-based). | Learner performs in the physical world; motion is captured, mapped to a character, and refined via capture–playback–retake cycles. |

| Psychological Affordances | Presence: “being there” in the virtual environment; agency: perceived control/ownership over actions in IVR. | Presence: creative–performative embodied engagement; agency: creative authorship over expressive motion (intent → action → mapped feedback). |

| Six mediators | Affective/cognitive mediators such as interest, intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, embodiment, cognitive load, and self-regulation. | Control and Active Learning; Reflective Thinking; Perceptual Motor Skills; Emotional Expressive; Artistic Innovation; Collaborative Construction. |

| Outcome emphasis | Knowledge outcomes (factual, conceptual, procedural) and transfer of learning. | Technical literacy; conceptual understanding; procedural mastery; adaptive innovation/transfer, with explicit emphasis on expressive performance quality and creative output. |

| Practical implication | Guides IVR lesson design to maximize learning while managing cognitive/affective constraints. | Guides MoCap lesson design (task briefs, critique loops, iteration, collaboration roles) to cultivate expressive motion, creativity, and transfer. |

| Model Segment | Proposition | Path(s) | Predictor | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology affordances → psychological affordances | P1 | 1 | Immersion | Presence |

| P2 | 2 | Interactivity | Presence | |

| P3 | 3 | Interactivity | Agency | |

| P4 | 4 | Representational fidelity | Presence | |

| P5 | 5 | Representational fidelity | Agency | |

| Psychological affordances → mediating constructs | P6 | 6–7 (7+) | Presence and Agency | Control and Active Learning |

| P7 | 8–9 (9+) | Presence and Agency | Reflective Thinking | |

| P8 | 10–11 (11+) | Presence and Agency | Perceptual–Motor Skills | |

| P9 | 12–13 (13+) | Presence and Agency | Emotional Expressive | |

| P10 | 14–15 (15+) | Presence and Agency | Artistic Innovation | |

| P11 | 16–17 (17+) | Presence and Agency | Collaborative Construction | |

| Mediating constructs → embodied learning and creative outcomes | P18 | 18 | Control and Active Learning | Embodied learning and Creative Outcomes |

| P19 | 19 | Reflective Thinking | Embodied learning and Creative Outcomes | |

| P20 | 20 | Perceptual–Motor Skills | Embodied learning and Creative Outcomes | |

| P21 | 21 | Emotional Expressive | Embodied learning and Creative Outcomes | |

| P22 | 22 | Artistic Innovation | Embodied learning and Creative Outcomes | |

| P23 | 23 | Collaborative Construction | Embodied learning and Creative Outcomes |

| Component | Paths | Operational Indicators and Feasible Data Sources (Triangulation) |

|---|---|---|

| Technology affordances | Paths 1–5 | System/pipeline logs (latency, dropped frames, tracking error, mapping stability); calibration success rate; brief instructor implementation checklist (immersion/interactivity/fidelity). |

| Presence and Agency | Paths 1–5 | Short presence/agency items after each capture–playback cycle (or post-session); behavior traces: intentional retakes, motion variants, active-performance time vs. passive observation. |

| Six mediators | Paths 6–17 (7+, 9+, 11+, 13+, 15+, 17+) | Rubrics and artifacts aligned to each construct: reflection notes (Reflective Thinking); motion-quality rubric (Perceptual Motor Skills); emotion clarity/congruence ratings (Emotional Expressive); novelty-appropriateness rubric (Artistic Innovation); collaboration rubric (role coordination, feedback density). |

| Learning Outcomes | Paths 18–23 | Knowledge checks; end-of-module performance task; portfolio artifacts; transfer task (apply learned motion principles to a new character brief/genre constraint). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, X.; Ibrahim, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, G. The Cognitive Affective Model of Motion Capture Training: A Theoretical Framework for Enhancing Embodied Learning and Creative Skill Development in Computer Animation Design. Computers 2026, 15, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020100

Jiang X, Ibrahim Z, Jiang J, Wang J, Liu G. The Cognitive Affective Model of Motion Capture Training: A Theoretical Framework for Enhancing Embodied Learning and Creative Skill Development in Computer Animation Design. Computers. 2026; 15(2):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020100

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Xinyi, Zainuddin Ibrahim, Jing Jiang, Jiafeng Wang, and Gang Liu. 2026. "The Cognitive Affective Model of Motion Capture Training: A Theoretical Framework for Enhancing Embodied Learning and Creative Skill Development in Computer Animation Design" Computers 15, no. 2: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020100

APA StyleJiang, X., Ibrahim, Z., Jiang, J., Wang, J., & Liu, G. (2026). The Cognitive Affective Model of Motion Capture Training: A Theoretical Framework for Enhancing Embodied Learning and Creative Skill Development in Computer Animation Design. Computers, 15(2), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020100