1. Introduction

Optimisation is the process of selecting the best decision vector from a feasible set defined by constraints, and it underpins many tasks in engineering design, economics and machine learning. In a typical single-objective formulation, the goal is to minimise (or maximise) an objective function

subject to bound constraints and general inequality/equality constraints, e.g.,

and

, where

may be continuous, discrete, or mixed. Practical optimisation problems often involve conflicting requirements (accuracy, cost, safety), expensive black-box simulations, measurement noise, and non-smooth or discontinuous responses, which strongly influences the choice of optimisation methodology [

1,

2].

Deterministic optimisation methods follow a fully prescribed sequence of computations: given the same initial conditions and parameters, they generate the same search trajectory and solution. This family includes classical mathematical programming approaches such as linear and quadratic programming, convex optimisation, and nonlinear programming (NLP). When the objective and constraints are smooth and (approximately) convex, gradient-based algorithms—including steepest descent, Newton/trust-region methods, sequential quadratic programming (SQP), and interior-point methods—can provide strong theoretical properties (e.g., convergence to stationary points and, in convex settings, global optimality) and fast local convergence rates [

1,

2]. Deterministic approaches are therefore widely used in parameter estimation, optimal control, structural sizing with well-behaved models, and resource allocation where derivatives (or accurate approximations) are available and constraints can be handled systematically via Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions and Lagrangian-based frameworks [

1]. Their main limitations arise when problems are highly non-convex, discontinuous, mixed-integer, or defined by black-box simulators: gradients may be unavailable or misleading, feasible regions may be fragmented, and the algorithms may become sensitive to initialisation or converge to poor local optima. Moreover, exact deterministic global methods for discrete or mixed-integer formulations can incur combinatorial complexity as dimensionality grows [

2].

Stochastic optimisation methods incorporate randomness into the search process and typically return solutions whose quality is described statistically over repeated runs. Randomness can enter through noisy objective evaluations, random sampling, or probabilistic update rules, enabling the search to explore multiple basins of attraction and reducing dependence on a single initial point [

2,

3]. A prominent example in machine learning is stochastic gradient-based learning (e.g., SGD and its variants), where random mini-batches provide scalable approximate gradients for large datasets [

3]. In broader engineering optimisation, stochastic methods are attractive for rugged landscapes, non-differentiable objectives, and simulation-based models where only function evaluations are available. The trade-offs are equally important: stochastic methods may require many evaluations, can exhibit run-to-run variability, and generally offer weaker theoretical guarantees for global optimality in finite time [

2].

Within stochastic optimisation, metaheuristic techniques are widely recognised for their flexibility and robustness; surveys and comparative studies consistently report their ability to adapt to diverse problem structures and maintain performance under uncertainty [

4,

5]. Metaheuristics provide general-purpose search frameworks rather than problem-specific solvers, relying on population diversity and stochastic operators to balance exploration (global search) and exploitation (local refinement). This balance is crucial: excessive exploitation can cause premature convergence to local optima, while excessive exploration can slow convergence and waste limited evaluation budgets [

5]. Metaheuristics are therefore commonly adopted for black-box engineering design, feature selection, hyperparameter tuning, and constrained optimisation where modelling assumptions required by deterministic solvers are difficult to satisfy [

6].

Recent years have witnessed a proliferation of nature-inspired metaheuristics. Examples include the Slime Mould Algorithm (SMA), Tunicate Swarm Algorithm (TSA), Runge–Kutta Optimiser (RKO), Equilibrium Optimiser (EO), and Manta Ray Foraging Optimisation (MRFO) [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Although these algorithms introduce diverse search operators, they share a recurring difficulty: maintaining an effective exploration–exploitation balance across different landscapes and constraint regimes. As a result, performance can be problem-dependent, motivating strategies that enhance robustness without sacrificing computational simplicity.

Combining complementary metaheuristics has become a widely adopted strategy to mitigate individual weaknesses and improve convergence. Metaheuristic hybrids integrate two or more algorithms, drawing on mechanisms such as evolutionary operators, swarm behaviours, or chaotic mappings to achieve improved search dynamics [

7,

12]. Comprehensive reviews document numerous combinations—for example, Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO) with Genetic Algorithms (GAs), Differential Evolution (DE) with PSO, and Grey Wolf Optimiser (GWO) with Sine–Cosine Algorithm (SCA)—each aiming to capitalise on complementary strengths [

7,

12]. Despite this rich body of hybrid designs, we are not aware of prior work that tightly integrates the Sine–Cosine Algorithm with the Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm within a unified population for continuous optimisation.

This paper addresses this gap by proposing AHA–SCA, a hybrid metaheuristic that interleaves the Sine–Cosine Algorithm (SCA) and the Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (AHA) within a single population. In the proposed design, SCA-style sinusoidal updates encourage wide-ranging exploration (particularly in early iterations), while AHA-style guided and territorial foraging intensifies the search near promising regions. Alternating these phases is intended to reduce premature convergence and improve final solution quality compared with using either component alone.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

We develop a novel AHA–SCA hybrid optimisation framework that couples SCA and AHA operators within a unified population to promote more effective exploration and exploitation behaviour.

We conduct extensive experiments on three benchmark suites (CEC2014, CEC2017, and CEC2022) and on constrained engineering design problems (welded beam, pressure vessel, tension/compression spring, speed reducer, and cantilever beam) using consistent settings and multiple independent runs.

We compare AHA–SCA against state-of-the-art optimisers using statistical significance tests and analyse convergence behaviour to clarify how the hybridisation affects search dynamics.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on metaheuristic optimisation and highlights recent hybrid algorithms.

Section 3 provides a detailed literature review of recent metaheuristic algorithms, discussing their strengths and weaknesses.

Section 4 describes the proposed AHA–SCA algorithm, including its motivation, mathematical model, pseudocode, and complexity analysis.

Section 5 details the experimental setup, including implementation details, statistical analysis, and benchmark functions.

Section 6 presents numerical results on benchmarks and engineering problems, followed by discussion.

Section 7 concludes this paper and outlines directions for future research.

3. Proposed Hybrid AHA–SCA Optimiser Algorithm

Metaheuristic algorithms have seen widespread adoption for tackling complex optimisation problems due to their ability to escape local minima and handle non-convex, high-dimensional search spaces. Classical approaches such as Genetic Algorithms, Simulated Annealing, and Particle Swarm Optimisation laid the foundations for population-based search. In the past decade, numerous nature-inspired algorithms have been proposed, including the Slime Mould Algorithm, Tunicate Swarm Algorithm, and Equilibrium Optimiser, each drawing on distinct biological or physical metaphors to design update rules. Comparative studies report that no single algorithm consistently outperforms others across all problem types, motivating the design of hybrids that combine complementary behaviours [

4,

28].

A number of recent works propose hybrid metaheuristics that alternate between exploration and exploitation phases. For instance, Ahmadianfar et al. coupled the Runge–Kutta Optimiser with Particle Swarm Optimisation to accelerate convergence, while Faramarzi et al. integrated Equilibrium Optimisation with Lévy flights for improved exploration. Sadiq et al. developed Manta Ray Foraging with local refinements to solve engineering designs, and Hashim et al. combined Archimedes Optimisation with chaos-based searches. These hybrids generally report faster convergence and better solution quality than their constituent algorithms but often at the expense of additional parameters or increased complexity. Very few studies have explored tight integration between Sine–Cosine and Hummingbird algorithms. The former excels at global exploration using oscillatory motions, whereas the latter offers effective local exploitation via guided foraging. This gap motivates the current study [

9,

10,

11,

29].

3.1. Inspiration

Hybrid SCA–AHA integrates two distinct sources of inspiration. The Sine–Cosine Algorithm uses the oscillatory behaviour of sine and cosine functions to update candidate solutions. As a solution approaches an optimum, the amplitude of the trigonometric perturbations decreases, enabling a smooth transition from exploration to exploitation.

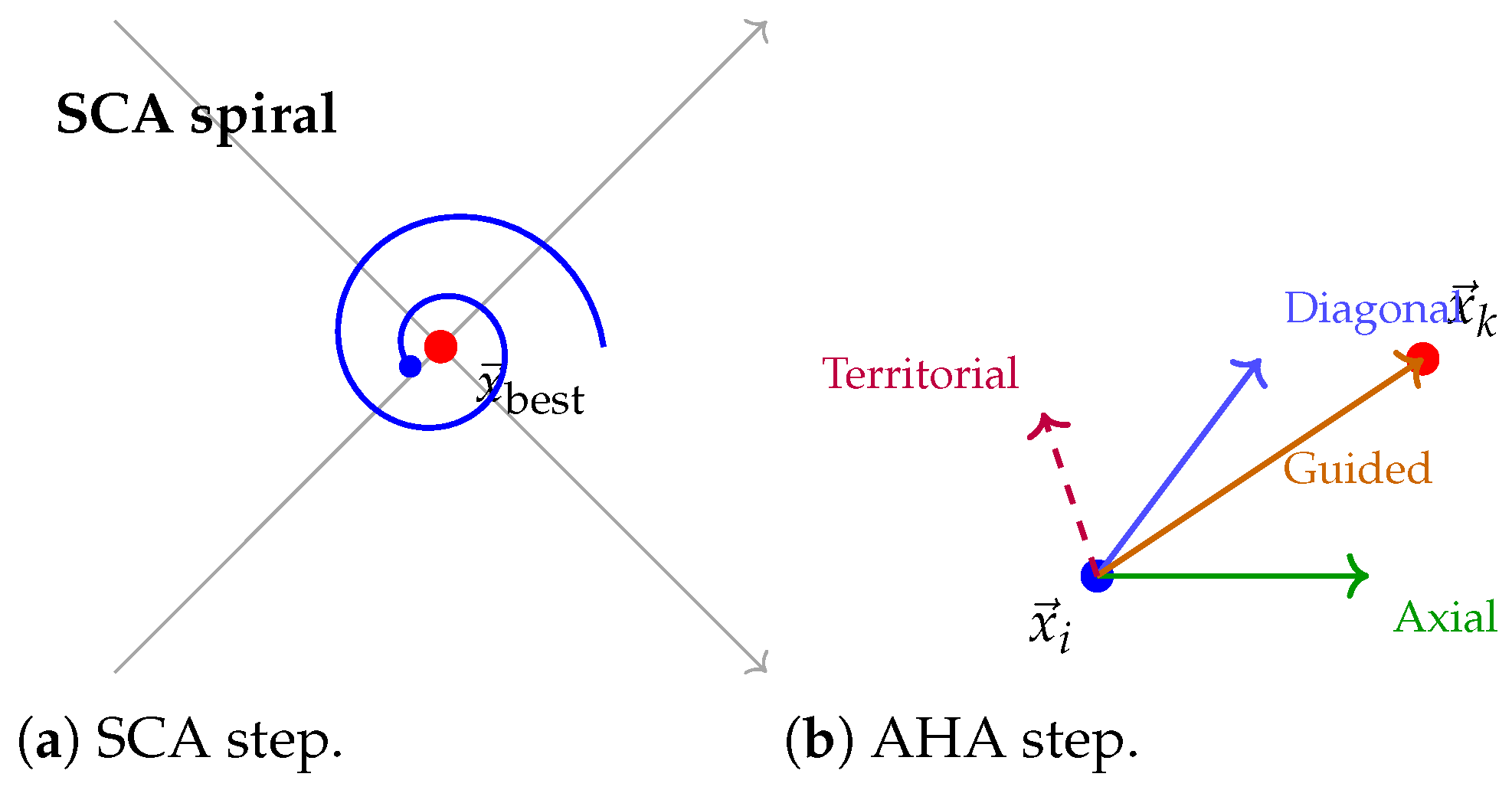

Figure 1 depicts a sine and cosine wave guiding a particle toward the global best. The particle’s position is adjusted using random angles and decaying amplitudes, producing a spiral-like trajectory. The SCA update mechanism was proposed by Mirjalili in 2016, and it employs random parameters

to modulate movement and switch between sine and cosine functions.

Zaho et al. [

26] introduced AHA as a bio-inspired optimiser: hummingbirds perform three types of flight—axial, diagonal, and omnidirectional—and employ guided foraging, territorial foraging, and migrating foraging. A visit table records the length of time a hummingbird has not visited each food source, influencing its movement decisions.

Figure 1b shows a stylised hummingbird approaching a flower using these flight patterns. In the hybrid algorithm, SCA operations alternate with AHA operations, leveraging both wave-based exploration and hummingbird-inspired exploitation.

3.2. Mathematical Model

Consider a population of N individuals (solutions) in an n-dimensional search space. Each individual’s position is denoted by and has an associated fitness value . The best solution found so far is . The algorithm runs for T iterations, alternating between SCA and AHA operations depending on whether the iteration index t is even or odd.

3.2.1. Sine–Cosine Update (Even Iterations)

The SCA phase updates each individual using trigonometric functions. A scaling parameter

linearly decreases from a constant

a to zero to control the step size:

where

a is typically set to 2. For each individual

i and each dimension

j, three additional random variables are drawn:

,

, and

. The updated position is computed as

where

denotes the absolute value. The sine function encourages movement toward the best solution, while the cosine function may move away from it, promoting exploration. The probability of selecting sine or cosine is governed by

. After updating all dimensions, the new position is clipped to the domain bounds

.

3.2.2. Hummingbird Flights and Foraging (Odd Iterations)

In odd iterations, the algorithm simulates hummingbird behaviours. Each hummingbird selects a flight pattern (axial, diagonal, or omnidirectional) by constructing a direction vector , where ones indicate active dimensions. As described by Zhao et al., the flight skills allow the hummingbird to move along a single axis, along a diagonal involving multiple axes, or in all dimensions.

Guided foraging.

With probability

, a hummingbird performs guided foraging. It identifies a target food source indexed by

k having the maximum unvisited time in the visit table. The new position is generated by

where

is normally distributed noise and ⊙ denotes elementwise multiplication. If the new fitness

improves upon

, the hummingbird moves to the new position; otherwise, its visit table entry is increased.

Territorial foraging.

Otherwise, the hummingbird performs territorial foraging around its current position:

with

as before. Only those components selected by

are perturbed. Again, the move is accepted if it yields a better fitness. After each update, the visit table is modified: each entry increases by one (ageing), and the entry corresponding to the chosen food source is reset to zero.

The AHA also supports a migrating foragingstrategy in which the population moves collectively to new regions. In our hybrid implementation, migrating foraging is omitted because SCA already performs global exploration.

3.3. Pseudocode

Algorithm 1 presents the pseudocode for the hybrid SCA–AHA. At each iteration, the algorithm decides which phase to execute based on the parity of

t. During the SCA phase, it computes

from Equation (

3) and updates each dimension using Equation (

4). During the AHA phase, it selects a direction vector, performs guided or territorial foraging according to Equation (

5) or Equation (

6), updates the visit table, and tracks the best solution.

| Algorithm 1 Hybrid Sine–Cosine and Artificial Hummingbird Optimiser |

![Computers 15 00035 i001 Computers 15 00035 i001]() |

3.4. Movement Strategy

The hybrid movement strategy alternates between wave-driven steps and hummingbird flights.

Figure 2 shows how these strategies complement each other. During even iterations, the SCA step (panel a) moves a particle around the best solution in a decaying spiral. The amplitude of the oscillations is controlled by

(Equation (

3)), and the choice between sine and cosine introduces directional diversity (Equation (

4)).

In odd iterations, the AHA step (panel b) selects a flight pattern based on a random decision: axial flight perturbs a single dimension, diagonal flight perturbs multiple dimensions, and omnidirectional flight perturbs all dimensions. The hummingbird chooses between guided foraging (flying toward a food source identified by the visit table) and territorial foraging (exploring locally). The noise term

in Equations (

5) and (

6) ensures stochasticity.

3.5. Exploration and Exploitation Behaviour

Hybrid SCA–AHA alternates between exploration and exploitation. The SCA phase emphasises exploration early on: the parameter

starts large and decreases linearly (Equation (

3)), causing large oscillatory movements that sample far from the current best solution. The random variables

further diversify the search, and the use of both sine and cosine functions prevents stagnation. As iterations progress,

shrinks, and the movement focuses near

, increasing exploitation.

The AHA phase predominantly exploits local regions by flying toward promising food sources (guided foraging) or performing territorial searches around the current position. However, the random selection of flight patterns and the inclusion of diagonal and omnidirectional flights enable exploration of multiple dimensions simultaneously. The visit table encourages diversification by increasing the unvisited time of food sources, making them more attractive targets later.

3.6. Complexity Analysis

Let

denote the cost of evaluating the objective function. During the SCA phase, each of the

N individuals updates

n dimensions and performs one fitness evaluation. The SCA phase thus requires

operations per iteration. During the AHA phase, each individual constructs a direction vector (cost

), performs one or two position updates and evaluations, and adjusts the visit table. The complexity of the AHA phase is therefore

. Since the algorithm alternates between phases, the worst-case per-iteration complexity is

Over T iterations, the total complexity is . Memory consumption is dominated by storing the population () and the visit table (). The quadratic visit table can be expensive for large populations, but in practice, N is chosen moderately. For very large populations, the memory requirement may become prohibitive; in such cases it may be necessary to limit N or adopt more memory-efficient data structures (for example, sparse or hashed visit tables) to maintain scalability.

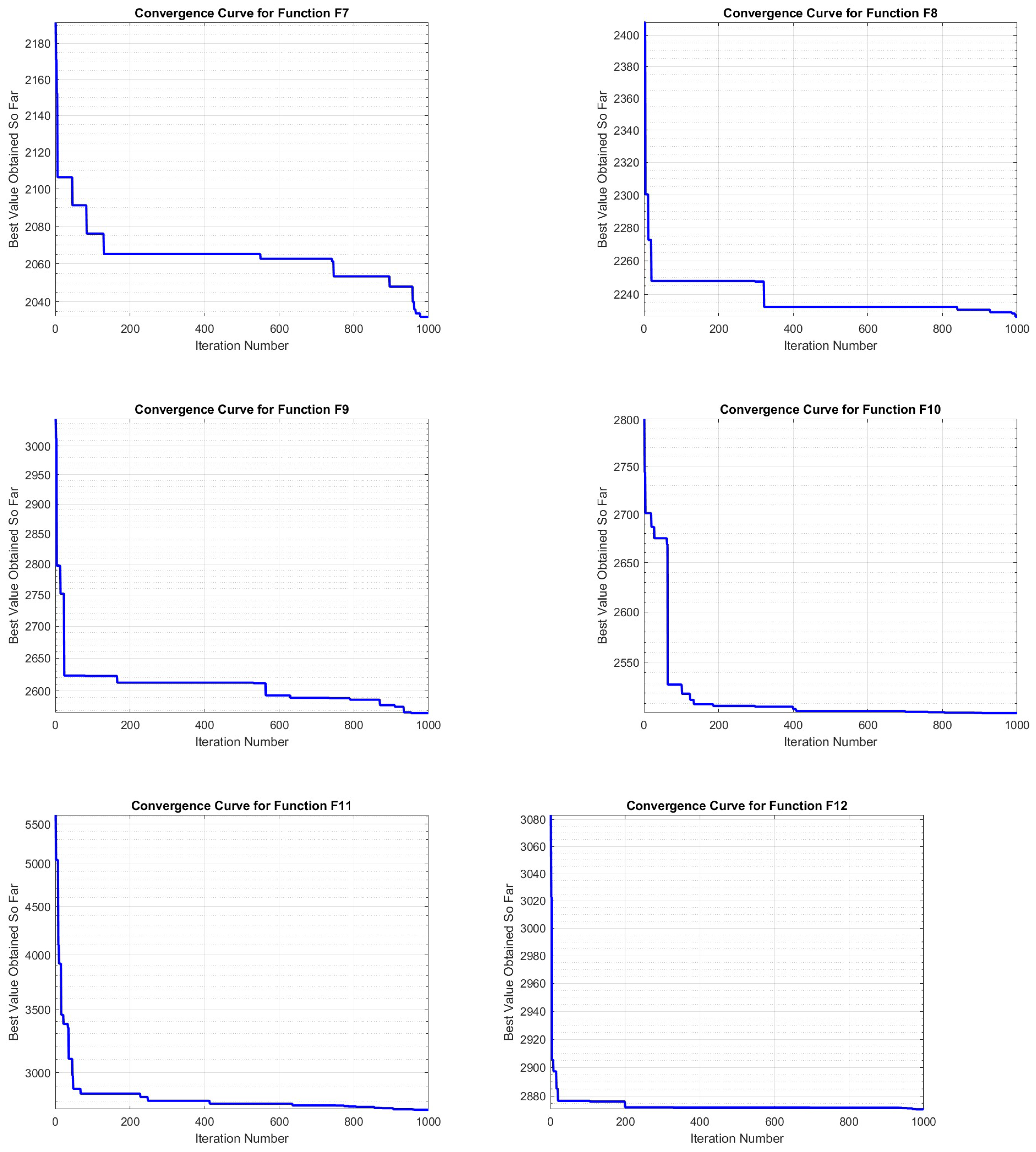

5. Parameterisation Framework for Benchmarking Optimisation Algorithms

For the effective benchmarking of optimisation algorithms in the CEC competitions of 2014, 2017, and 2022, the establishment of uniform parameters is indispensable. These parameters ensure a standardised environment that is crucial for the equitable evaluation of various evolutionary algorithms’ performances. Detailed numerical results (formerly

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5) are provided in the Appendix; in the main text we focus on key statistics and visual comparisons.

The selection of a 30-individual population size and a ten-dimensional space strikes a practical balance between computational efficiency and the complexity required for accurate testing. A maximum of 1000 function evaluations is adopted to reflect scenarios with limited evaluation budgets; this relatively small number provides the algorithms an opportunity to exhibit early convergence without imposing excessive computational demands. Notably, many CEC benchmarks allocate at least evaluations for ten-dimensional problems, so our limit is lower than the state of the art and may restrict long-run convergence. The choice underscores the applicability of the proposed method to resource-constrained engineering tasks; nevertheless, evaluating AHA–SCA with larger budgets remains an interesting direction for future work. A consistent search range of allows for broad and equal testing conditions across different algorithms.

5.1. Evaluating Optimisation Algorithms Through Statistical Methods

In this thorough investigation into the performance of various optimisation algorithms, we employed fundamental statistical measures: the mean, standard deviation, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The mean, indicative of central tendency, averages the performance outcomes across several trials, providing a comprehensive overview of expected performance levels. To complement this, the standard deviation measures the extent of variability from the average, shedding light on the consistency and robustness of the algorithms under different conditions. These statistics are indispensable for understanding the algorithms’ stability and their predictable performance.

Further, to explore the statistical relevance of differences between the performances of diverse algorithm groups, we conducted the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. This test helps to statistically validate whether observed performance discrepancies are significant, enhancing the reliability of our comparative analysis.

5.2. Review of Comparative Algorithms

In this analysis, we conducted a rigorous evaluation of a variety of optimisation algorithms to determine their effectiveness. The assessment encompassed a broad range of algorithms including the following: Sea-Horse Optimiser (SHO) [

30], Sine–Cosine Algorithm (SCA) [

31], Horned Lizard Optimisation Algorithm (HLOA) [

32], and Butterfly Optimisation Algorithm (BOA) [

15]; Moth-Flame Optimisation (MFO) [

33], Whale Optimisation Algorithm (WOA) [

34], Multi-Verse Optimiser (MVO) [

35], and Reptile Search Algorithm (RSA) [

36]; and Geometric Mean Optimiser (GMO) [

37], Grey Wolf Optimiser (GWO) [

38], Arithmetic Optimisation Algorithm (AOA) [

39], Golden Jackal Optimisation (GJO) [

40], Mountain Gazelle Optimiser (MGO) [

41], Flow Direction Algorithm (FDA) [

42], and Giant Trevally Optimiser (GTO) [

43].

7. AHASCA Applications in Engineering Design Problems

This subsection evaluates the proficiency and effectiveness of the SCA-AHA algorithm in addressing engineering-related challenges, particularly constrained optimisation problems. The assessment focuses on seven specific engineering design cases: weld beam design, pressure vessel configuration, rolling element bearing formulation, cantilever beam structure, tension/compression spring mechanism, and gear train assembly. These examples are chosen to showcase the algorithm’s applicability, versatility, and robustness in solving practical engineering optimisation problems.

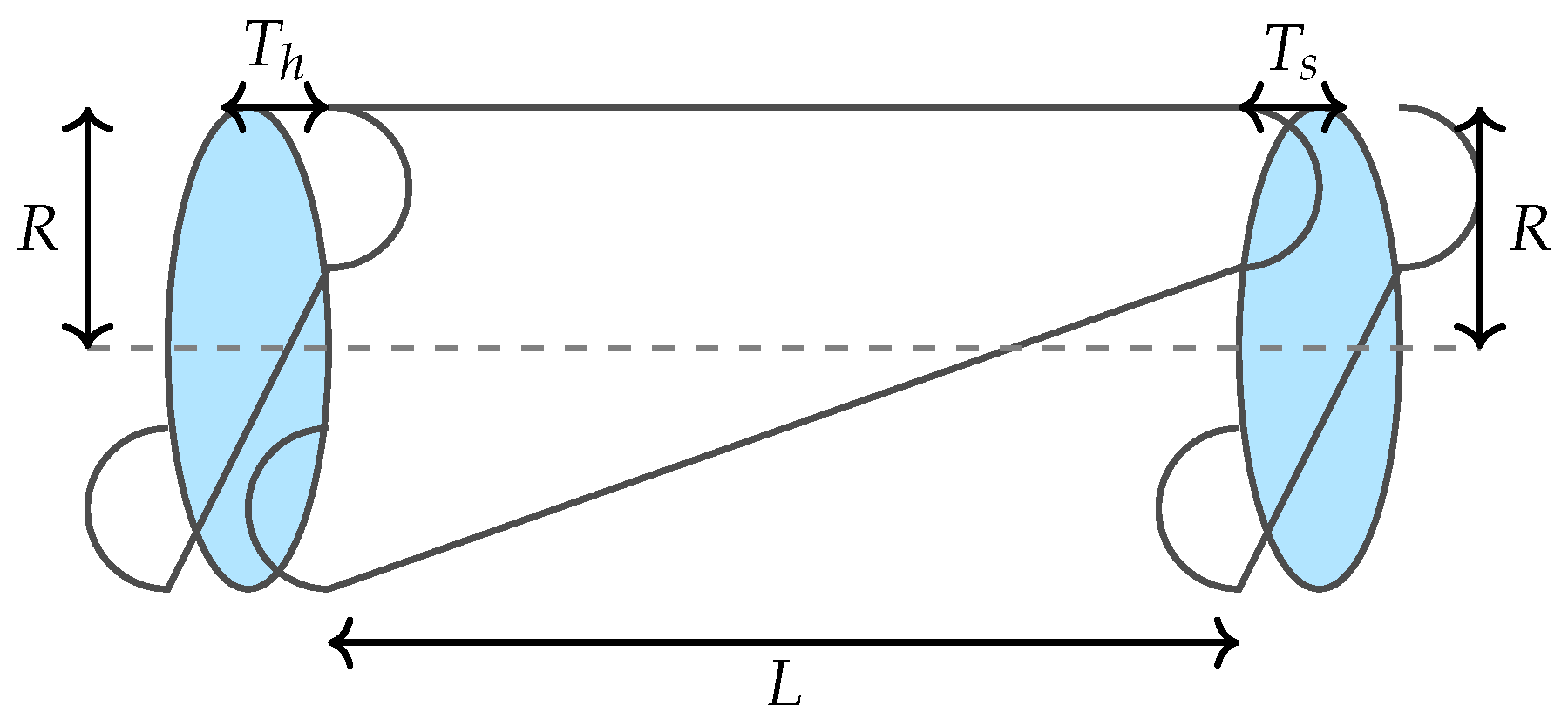

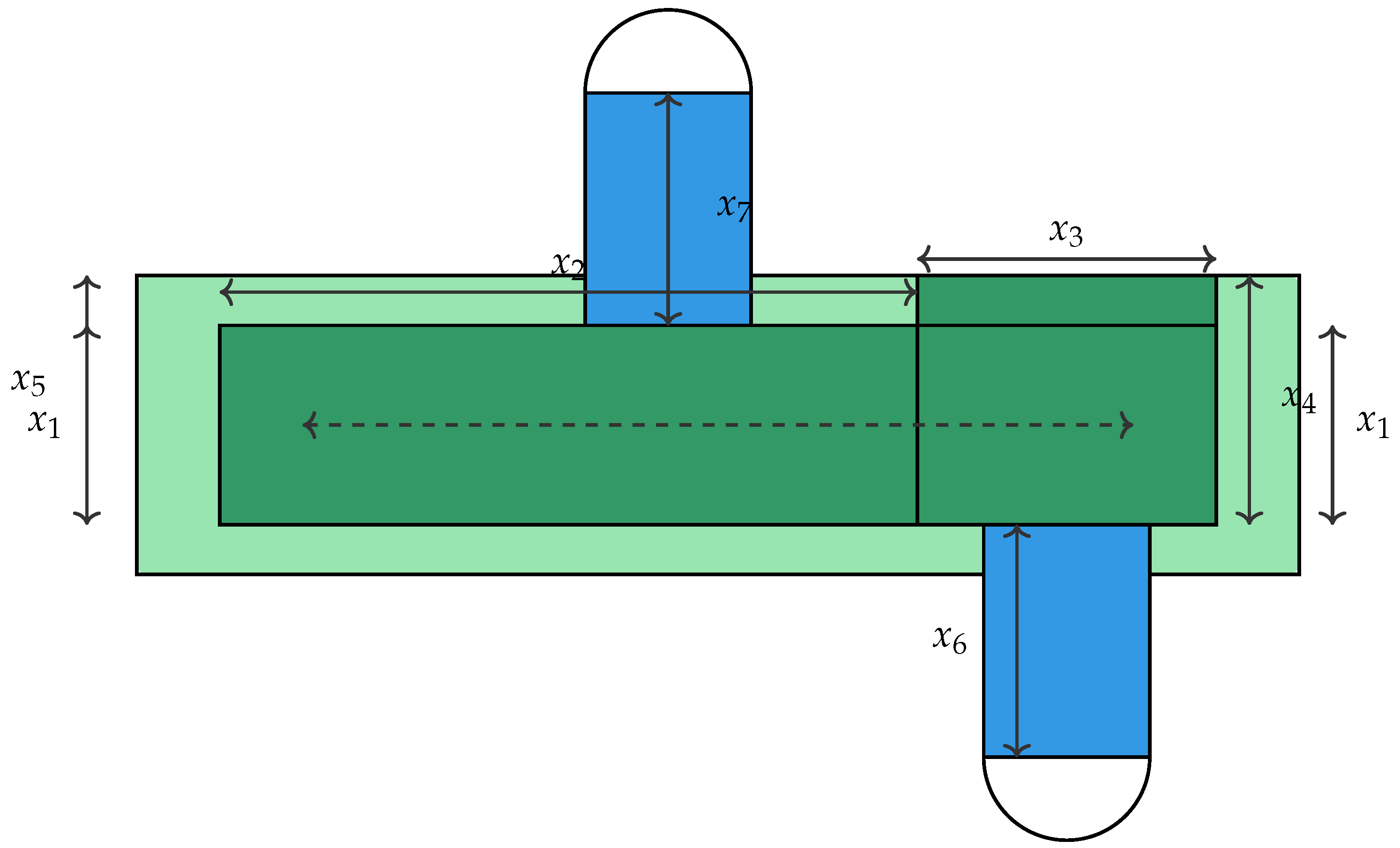

7.1. Pressure Vessel Design Problem

A pressure vessel is a closed container designed to hold gases or liquids at a pressure substantially above atmospheric levels, as illustrated in

Figure 5. These vessels are typically cylindrical with hemispherical ends and are fundamental to numerous engineering applications. The challenge of optimising the design of pressure vessels to enhance efficiency and safety while minimising costs was first articulated by Sandgren [

44] and continues to be a significant area of research. The construction of the pressure vessels adheres to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME)’s boiler and pressure vessel code, focusing on a vessel designed to operate at

and hold a minimum of

.

The optimisation variables include the shell thickness (

), the head thickness (

), the inner radius (

R), and the cylindrical section length excluding the heads (

L), with the thicknesses constrained to multiples of

. This optimisation problem is mathematically formulated as follows [

45]:

The objective function to be minimised is given by

The constraints ensuring structural integrity and compliance with ASME standards are

The variable bounds are set as

AHASCA exhibits exemplary performance in optimising the Pressure Vessel Design Problem, as demonstrated by the statistical results presented in

Table 5. AHASCA achieves minimum, mean, and maximum values of 5885.333, with an extraordinarily low standard deviation of

, indicating exceptional consistency and reliability in its optimisation capability.

This performance is significantly superior when compared with other optimisers like the Salp Swarm Algorithm (SSA) and Moth Flame Optimiser (MFO). SSA has a minimum value of 5927.544 but a mean much higher at 6087.173 and a maximum of 6252.051, coupled with a standard deviation of 136.4673, which highlights greater variability in its results. Similarly, MFO starts at the same minimum as AHASCA but diverges considerably in the mean (6449.973) and maximum (6994.548) values, with a very high standard deviation of 453.9395, suggesting less predictability and stability.

The Sine–Cosine Algorithm (SCA) and Ant Lion Optimiser (AOA) also show less favourable outcomes, with SCA recording a minimum of 6300.01, a mean of 6720.458, and a maximum of 7562.309, alongside a standard deviation of 455.0258. AOA, in particular, shows the least optimal performance with the highest minimum value of 6718.876, escalating to an alarming mean of 8684.574 and a maximum of 11,376.98, with an extremely high standard deviation of 1586.498, indicating poor performance consistency.

Among other algorithms, the Adaptive Harmony Algorithm (AHA) closely matches AHASCA in terms of minimum, mean, and maximum values, achieving similarly low variability but with a slightly higher standard deviation of 0.111128. This comparison underscores the efficiency and effectiveness of AHASCA, which not only provides optimal solutions but does so with remarkable precision and repeatability, making it a highly preferable choice for engineering applications where both accuracy and consistency are crucial.

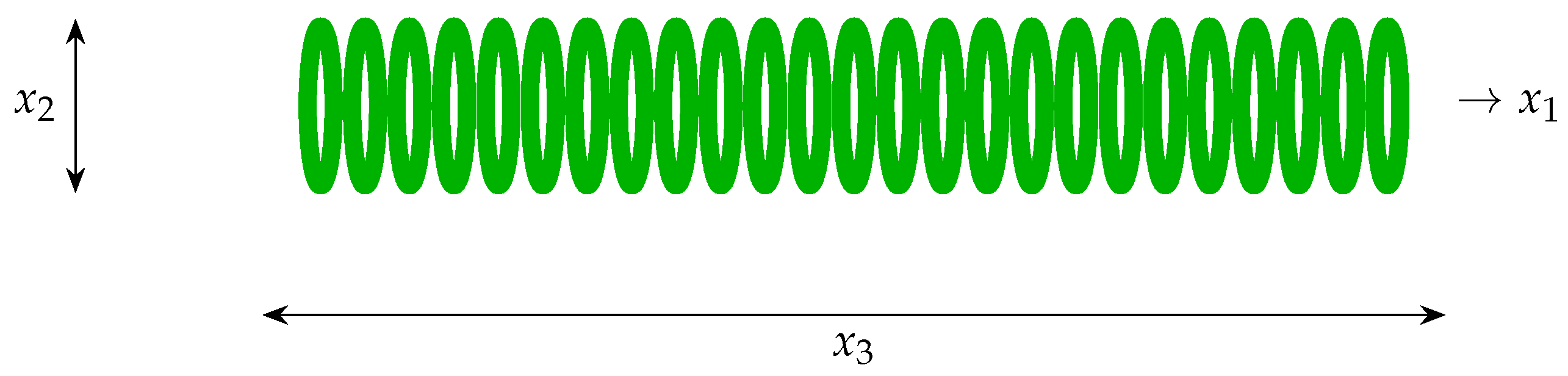

7.2. Spring Design Optimisation Problem

The Spring Design Optimisation Problem is a well-established challenge in engineering aimed at determining the ideal dimensions of a mechanical spring to meet specific performance criteria while minimising material and production costs [

46]. The critical design parameters as shown in

Figure 6 include the wire diameter (

d), coil diameter (

D), and number of active coils (

N), which significantly influence the spring’s strength, flexibility, and space occupation.

The primary goal of this optimisation is to reduce the material cost by minimising the weight or volume of the spring [

47]. The design must ensure that the spring can endure operational stresses without yielding (stress failure), resist buckling under compressive loads, and function without resonating at damaging frequencies. These requirements lead to several constraints, including limitations on shear stress (

), permissible deflections (

y), and adequate free length to prevent solid compression and surging.

The problem is generally formulated as a nonlinear optimisation task where the objective function and constraints are expressed in terms of the design variables d, D, and N. The choice of materials, environmental conditions, and load specifications are also crucial in defining the optimal design. Various solution methods can be applied, from analytical and numerical approaches such as finite element analysis to heuristic algorithms like Genetic Algorithms and other evolutionary strategies, each providing distinct benefits depending on the design’s complexity and specific needs.

The optimisation of the spring is characterised by the following mathematical formulation:

where

is a cost function dependent on the design parameters.

The constraints are defined as

Penalty terms and g are integrated into the objective function to penalise designs that fail to satisfy the constraints, with indicating violations and g quantifying their severity.

In the context of the Spring Design Optimisation Problem, the AHASCA has shown notable efficacy, as detailed in the results presented in

Table 6. AHASCA demonstrated superior performance with the best objective score of 0.012665, optimising design variables for wire diameter, coil diameter, and number of active coils effectively. Its results closely align with other top-performing algorithms like MFO, GWO, and FDA, indicating competitive optimisation capabilities. In contrast, algorithms such as SCA, GJO, and MGO showed less efficient solutions, especially with higher coil counts, reducing material efficiency. AOA notably underperformed, with both a higher score and suboptimal variable settings. AHASCA’s low standard deviation further highlights its robustness and reliability, making it well-suited for precise engineering applications.

In the Spring Design Optimisation Problem, the AHASCA demonstrates outstanding results, as evidenced in the data provided in

Table 7. AHASCA achieves not only the lowest minimum value of 0.012665 but also maintains this as both the mean and maximum, indicating an exceptionally consistent performance across multiple runs with a negligible standard deviation of

. This precision highlights AHASCA’s ability to reliably find and replicate the optimal solution without deviation.

Compared to other optimisers, AHASCA results are superior in terms of both the achieved minimum values and the narrow spread between the minimum, mean, and maximum values. For instance, Salp Swarm Algorithm (SSA) and Moth Flame Optimiser (MFO) have similar minimal scores but higher mean and maximum values, reflecting greater variability in their results. Specifically, MFO’s mean of 0.013195 and a maximum of 0.014389 with a standard deviation of 0.000816 illustrate less stability compared to AHASCA.

Some algorithms like the Grey Wolf Optimiser (GWO) and Genetic Job Optimisation (GJO) show competitive performances with low standard deviations, but they still do not match the absolute precision of AHASCA. Meanwhile, the Hooke–Jeeves Optimisation Algorithm (HLOA) and Multi-Verse Optimiser (MVO) exhibit much larger deviations from their minimum values, as indicated by their higher standard deviations and maximum values, which suggests a significant decrease in performance consistency.

Among the competitors, the Progressive Optimisation Algorithm (POA) and Adaptive Harmony Algorithm (AHA) come closest to matching AHASCA in consistency and precision, with AHA demonstrating an almost identical performance in terms of stability and repeatability, evidenced by its minuscule standard deviation of .

7.3. Speed Reducer Design Problem

The Speed Reducer Design Problem as shown in

Figure 7 is a classic engineering optimisation challenge aimed at finding the optimal dimensions for a speed reducer to meet specified performance requirements while minimising material and production costs [

48]. Key design variables include the face width (

b), module of teeth (

m), number of teeth on the pinion (

p), lengths of the first (

) and second (

) shafts between bearings, and the diameters of these shafts (

and

). Each variable critically affects the speed reducer’s performance attributes such as strength, flexibility, and space occupation [

49].

The main objective of this optimisation is to minimise the total weight of the speed reducer. Additionally, the design must ensure that the speed reducer can withstand operational stresses without yielding (stress failure), prevent buckling under compressive loads, and operate without resonating at harmful frequencies [

50]. These operational requirements necessitate multiple constraints in the design process, which include limits on shear stress (

), permissible deflections (

y), and sufficient free length to avoid solid compression and surging.

This problem is typically modelled as a nonlinear optimisation challenge where the objective function and constraints are formulated in terms of the design variables b, m, p, , , , and . Material selection, environmental conditions, and load specifications also play a crucial role in determining the optimal design. Various computational methods, ranging from analytical approaches and numerical methods like finite element analysis to heuristic algorithms such as Genetic Algorithms and other evolutionary strategies, can be employed to solve this problem. Each method offers specific advantages depending on the complexity and requirements of the design task.

The decision variables for the Speed Reducer Design Problem are defined as

where each variable corresponds to a specific design dimension.

The objective function to be minimised is

The constraints are specified as follows:

Variable bounds are set as follows:

In the Speed Reducer Design Problem, the AHASCA excels in achieving a highly consistent and optimal performance, as shown in

Table 8. AHASCA achieves a minimum, mean, and maximum value of 2994.471, with an exceptionally low standard deviation of

. This indicates not only AHASCA’s ability to find an optimal solution but also its consistency in replicating this result across multiple runs, which is crucial for reliability in practical engineering applications.

Comparatively, other optimisation algorithms exhibit varying levels of performance and consistency. For example, the Salp Swarm Algorithm (SSA) and Moth Flame Optimiser (MFO) also achieve competitive minimum values but have higher mean and maximum values, with standard deviations of 11.4687 and 20.28279, respectively, suggesting less consistency in their optimisation results. Specifically, MFO shows significant variability, which might affect the reliability of the solutions it provides in a real-world setting.

The Sine–Cosine Algorithm (SCA) and Ant Lion Optimiser (AOA) both perform less optimally not only in terms of achieving higher minimal values but also in exhibiting much larger standard deviations of 52.77254 and 46.56557, respectively, indicating significant variability in their results. These large deviations from the mean suggest these algorithms might struggle with stability in this particular design problem.

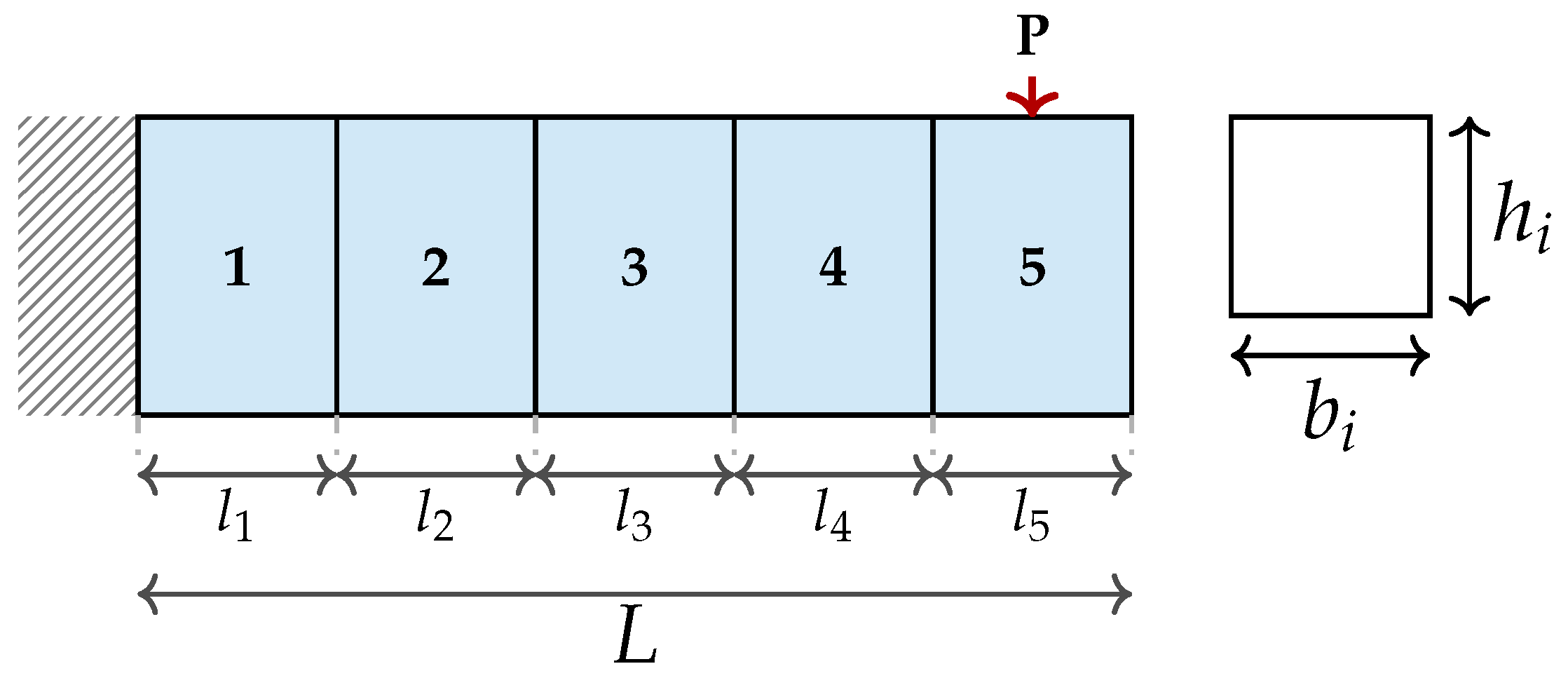

7.4. Cantilever Beam Design Optimisation Problem

The Cantilever Beam Design Optimisation Problem as shown in

Figure 8 represents a significant challenge in structural engineering, focusing on determining the optimal dimensions of a cantilever beam to meet specific performance criteria while minimising material and manufacturing costs [

51]. The critical design variables include the beam’s length (

L), width (

b), and height (

h), each significantly impacting attributes like stiffness, strength, and weight.

The primary aim of this optimisation is to reduce the overall weight of the beam and lowering costs while ensuring that the beam remains sufficiently resistant to bending and deflection under load [

52]. The design must also prevent material failure under maximum expected loads (stress failure) and ensure stability against lateral buckling. These operational requirements necessitate several constraints, including limits on maximum bending stress (

), allowable deflection (

y), and buckling load factors.

This optimisation challenge is typically modelled as a nonlinear task where the objective function and constraints are expressed in terms of the design variables L, b, and h. Material properties, environmental conditions, and the specifics of the applied loads are crucial in determining the optimal design. Various computational methods can be applied to solve this problem, ranging from traditional analytical approaches and simulation techniques like finite element analysis to modern heuristic methods such as Genetic Algorithms and Simulated Annealing. Each technique offers specific benefits depending on the complexity and requirements of the design task.

The mathematical description of the cantilever beam design problem is defined as follows:

The optimisation problem is formulated as

subject to the constraint:

and the variable bounds:

Equations provide a complete description of the optimisation model, which aims to minimise the objective function subject to a nonlinear constraint and variable bounds.

In the Cantilever Beam Design Optimisation Problem, the AHASCA showcases exemplary precision and consistency, as highlighted by the statistical metrics presented in

Table 9. AHASCA achieves the minimum, mean, and maximum values of 1.339956, with an incredibly low standard deviation of

. This near-zero variance not only indicates AHASCA’s ability to consistently find the optimal solution but also demonstrates its exceptional stability across multiple runs.

The Salp Swarm Algorithm (SSA) and Moth Flame Optimiser (MFO) also achieve competitive minimum values but with higher standard deviations of and 0.0005, respectively. These higher deviations suggest less consistency compared to AHASCA. MFO, in particular, shows a relatively wider range in its results, indicating a potential for greater variability in achieving optimal results.

Other algorithms like the Sine–Cosine Algorithm (SCA) and Ant Lion Optimiser (AOA) exhibit not only higher minimum values but also significantly larger standard deviations of 0.011464 and 0.009419, respectively. These values highlight the challenges these algorithms face in achieving and maintaining an optimal solution within this design problem, suggesting a potential lack of robustness or adaptability to the specific constraints and requirements of the Cantilever Beam Design.

8. Conclusions

This paper introduced AHA–SCA, a hybrid optimiser that interleaves the Sine–Cosine Algorithm’s oscillatory search with the Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm’s guided and territorial foraging. The design is intentionally minimal: even iterations apply SCA with a linearly decaying amplitude to promote broad, controllable exploration; odd iterations apply AHA, using axial/diagonal/omnidirectional flight patterns and a visit table to intensify search around promising regions. The result is a clear exploration–exploitation schedule with time per iteration and modest implementation overhead.

Comprehensive experiments on CEC2014, CEC2017, and CEC2022 demonstrate that AHA–SCA is a strong general purpose optimiser. Relative to stand-alone AHA and SCA and to several recent baselines, the hybrid achieves the following: (i) it converges faster in early and mid phases, (ii) it achieves lower mean/median errors with noticeably smaller standard deviations on many functions, and (iii) it shows improved robustness against premature convergence on rugged, composite landscapes. In constrained engineering studies (e.g., welded beam and pressure vessel), the method attains best or near-best feasible designs while respecting all constraints, underscoring its practical utility.

Future directions include the following: (i) self-adaptive or reward-driven switching between SCA and AHA phases, (ii) parameter control for SCA amplitude and AHA noise, (iii) more sophisticated constraint handling (e.g., feasibility rules and adaptive penalties), (iv) multi-objective and large-scale extensions, (v) parallel/distributed implementations, and (vi) formal convergence analysis.