Error-Guided Multimodal Sample Selection with Hallucination Suppression for LVLMs

Abstract

1. Introduction

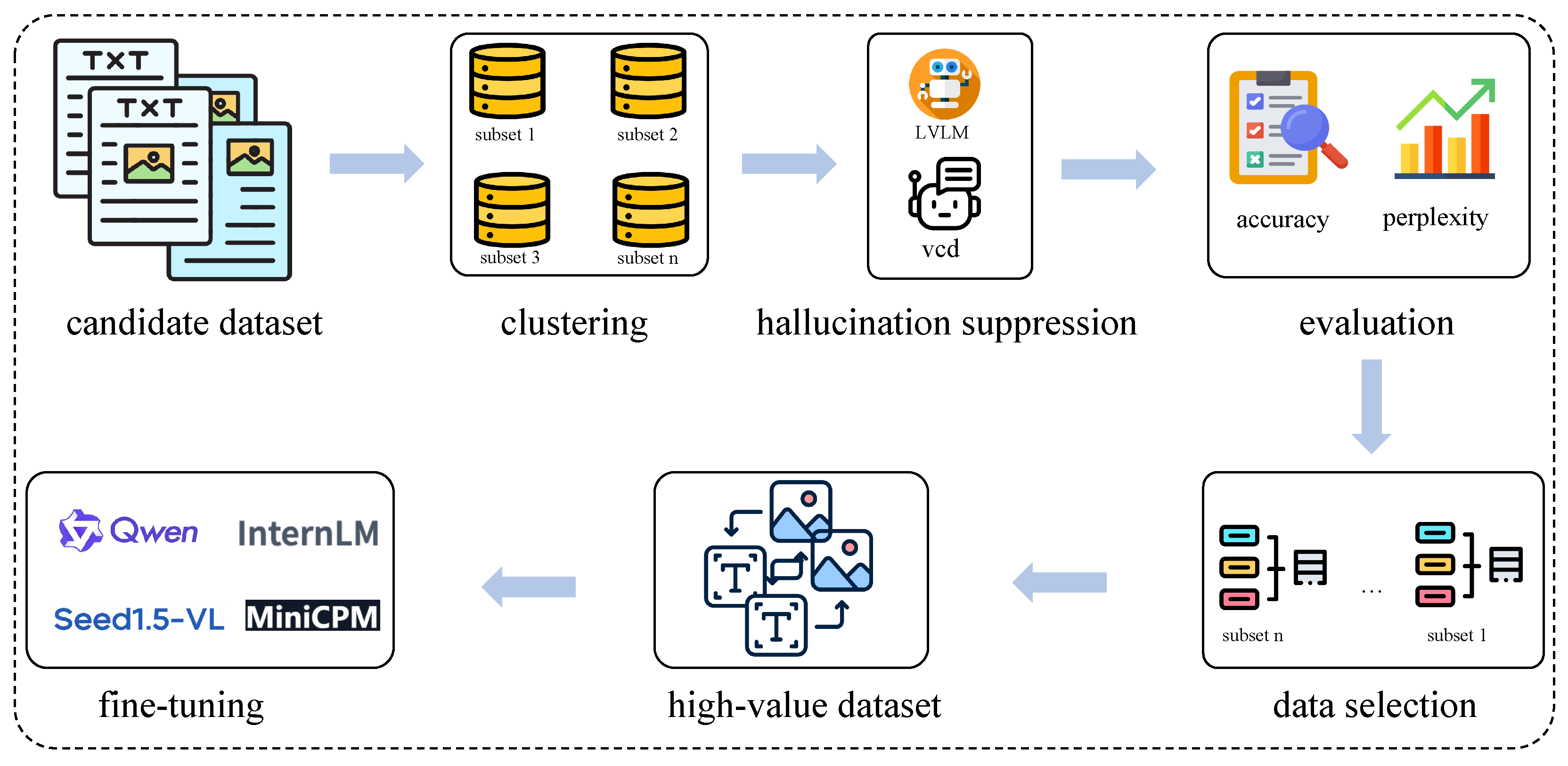

- An error-guided multimodal training data selection method: This approach selects samples based on model error-prone instances and output difficulty, effectively improving visual instruction fine-tuning performance.

- A hallucination suppression module: This module enhances the effectiveness of data selection. By identifying high-difficulty samples, it exposes the model’s weaknesses in multimodal understanding and reasoning, thereby increasing the learning value of the selected data.

- Extensive experimental validation: Results demonstrate that the proposed strategy not only significantly improves fine-tuning efficiency and model performance but also enhances the robustness and generalization capability of multimodal large models.

2. Related Work

2.1. LVLMs

2.2. Instruction Construction

3. Method

3.1. Clustering

3.2. Hallucination Suppression

- 1.

- Dual-Path Decoding Mechanism

- Standard Decoding Path: For an input image i and a query q, the output at time step t is .

- Perturbed Decoding Path: The original image i is subjected to perturbation; for example, by adding random noise or applying a mask, resulting in a perturbed image , the output at time step t is .

- 2.

- Contrastive Decoding: The final contrastive decoding is computed as:where denotes the contrastive coefficient.

3.3. Evaluation

3.4. Data Selection

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset Description

4.1.1. InsPLAD

4.1.2. PowerQA

4.2. Model and Training Details

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.3.1. InsPLAD Metrics

4.3.2. PowerQA Metrics

- Cosine Similarity: Measures the similarity between two non-zero vectors in an inner product space. We used a TF-IDF vectorization approach to represent the model-generated and ground-truth answers.

- BLEU Score: A standard metric for evaluating the quality of machine-generated text by measuring the correspondence between it and a set of reference texts.

- GPT-4o Score: Given the limitations of automated metrics in capturing semantic nuance and hallucination, we prompted the GPT-4o model to act as an evaluator, scoring the quality of our model’s generated answers on a scale from 0 to 10. The scoring criteria strictly followed these rules:

- -

- 10: Semantically equivalent to the label, with consistent key information and no contradictions.

- -

- 8–9: Basically equivalent, with only minor stylistic differences.

- -

- 6–7: Generally consistent but missing important details or with slight deviations.

- -

- 4–5: Partially matching; many key points are missing or ambiguous.

- -

- 1–3: Largely inconsistent or conflicting with the label.

- -

- 0: Clearly contradictory, fabricated facts, or completely irrelevant.

4.3.3. Baselines

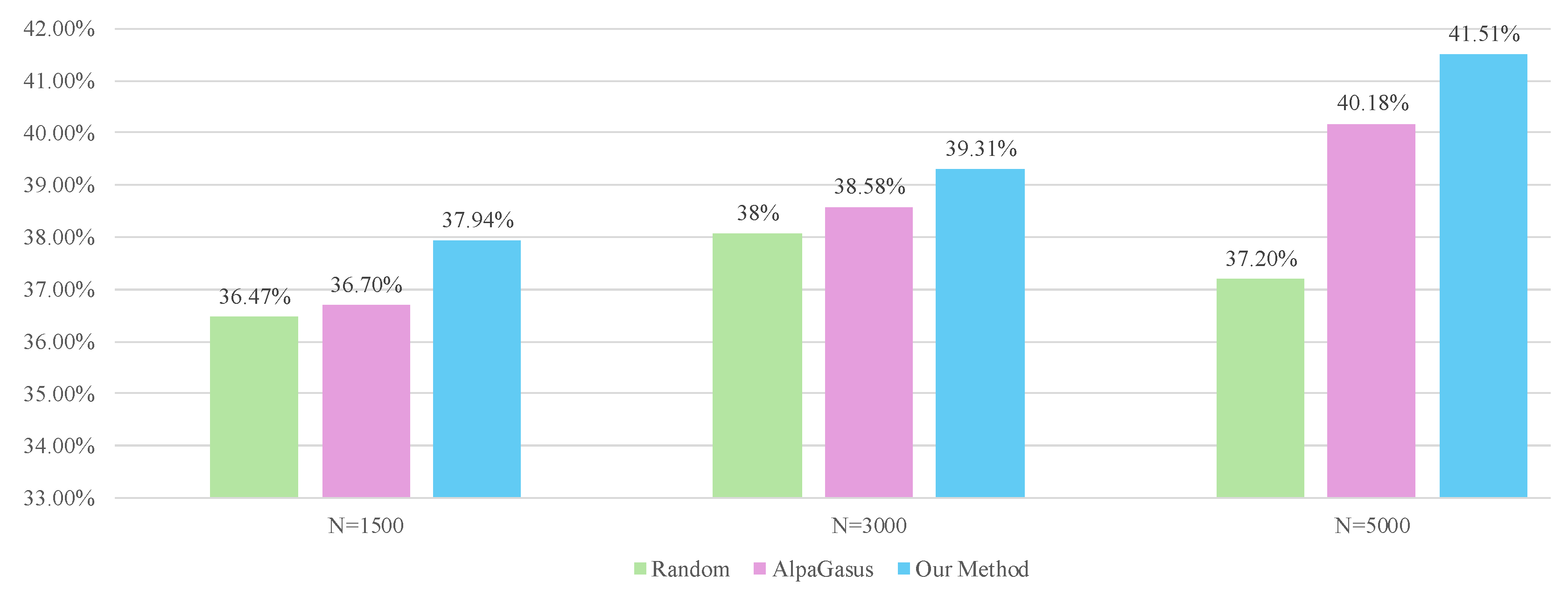

- Base: Directly uses the original LVLM to generate outputs, without any additional fine-tuning or data selection.

- Random_N: Randomly selects N samples from the training set for fine-tuning, where N denotes the number of selected samples.

- AlpaGasus_N: Uses the AlpaGasus method to select N samples from the training set for fine-tuning.

- Choice_N: The method proposed in this paper, which selects N high-value samples from the training set for fine-tuning.

4.4. Results

4.4.1. Main Results

4.4.2. Data Selection Metrics

4.4.3. Class Numbers

4.4.4. Generalization

5. Case Study

6. Discussion

7. Limitation and Future Work

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comanici, G.; Bieber, E.; Schaekermann, M.; Pasupat, I.; Sachdeva, N.; Dhillon, I.; Blistein, M.; Ram, O.; Zhang, D.; Rosen, E.; et al. Gemini 2.5: Pushing the frontier with advanced reasoning, multimodality, long context, and next generation agentic capabilities. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.06261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; et al. Qwen2.5-vl technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.13923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Lee, Y.J. Improved baselines with visual instruction tuning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 26296–26306. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Chen, J.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Elhoseiny, M. Minigpt-4: Enhancing vision-language understanding with advanced large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.10592. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Ye, Q.; Yan, M.; Shi, Y.; Ye, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Bi, B.; Qian, Q.; Wang, W.; et al. mplug-2: A modularized multi-modal foundation model across text, image and video. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 38728–38748. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Tiong, A.; Zhao, J.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Fung, P.N.; Hoi, S. Instructblip: Towards general-purpose vision-language models with instruction tuning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 49250–49267. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Gao, Z.; Gu, L.; Pu, H.; Cui, L.; Wei, X.; Liu, Z.; Jing, L.; Ye, S.; Shao, J.; et al. Internvl3. 5: Advancing open-source multimodal models in versatility, reasoning, and efficiency. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.18265. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Yu, T.; Tian, H.; Fu, C.; Li, P.; Zeng, J.; Xie, W.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; et al. Mm-rlhf: The next step forward in multimodal llm alignment. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.10391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Xu, Q.; Yao, Y.; Chen, D.; Lu, X.; Cui, G.; Dang, Y.; He, T.; et al. Rlaif-v: Open-source AI feedback leads to super gpt-4v trustworthiness. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 19985–19995. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Lin, K.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Yacoob, Y.; Wang, L. Mitigating hallucination in large multi-modal models via robust instruction tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.14565. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, H.; Hu, A.; Yan, M.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, F.; Zhou, J. mplug-owl3: Towards long image-sequence understanding in multi-modal large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.04840. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Wu, B.; He, M.; Huang, T. Svit: Scaling up visual instruction tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.04087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, T.; Liu, C.; Ding, H.; Shi, Y.; Cheng, F.; Xiao, H.; Wen, B.; Yang, F.; Gao, T.; et al. Taskgalaxy: Scaling multi-modal instruction fine-tuning with tens of thousands vision task types. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.09925. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Huang, X.; Zheng, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Yoshie, O.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Mm-instruct: Generated visual instructions for large multimodal model alignment. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.19736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Meng, L.; Weng, Z.; He, B.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, Y.G. To see is to believe: Prompting gpt-4v for better visual instruction tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.07574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liu, P.; Xu, P.; Iyer, S.; Sun, J.; Mao, Y.; Ma, X.; Efrat, A.; Yu, P.; Yu, L.; et al. Lima: Less is more for alignment. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 55006–55021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, K.; Zhao, W.X.; Gao, D.; Li, Y.; Wen, J.R. Less is more: Data value estimation for visual instruction tuning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.09559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lu, K.; Xu, B.; Lin, J.; Su, Q.; Zhou, C. Self-evolved diverse data sampling for efficient instruction tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.08182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hui, B.; Xia, X.; Yang, J.; Yang, M.; Zhang, L.; Si, S.; Chen, L.H.; Liu, J.; Liu, T.; et al. One-shot learning as instruction data prospector for large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.10302. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, W.; Sun, L. Instructiongpt-4: A 200-instruction paradigm for fine-tuning minigpt-4. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12067. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Kang, Y.; Sun, L. Instruction mining: High-quality instruction data selection for large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.06290. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Cheng, N.; Wang, J.; Zhou, T.; Xiao, J. From quantity to quality: Boosting llm performance with self-guided data selection for instruction tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12032. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Q.; Zong, C.; Zhang, J. MoDS: Model-oriented Data Selection for Instruction Tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.15653. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, D.; Xiao, X.; Hecker, A.; Tresp, V.; Ma, Y. Prism: Self-pruning intrinsic selection method for training-free multimodal data selection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12119. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Mishra, S.; Chiang, J.; Mirzasoleiman, B. Smalltolarge (s2l): Scalable data selection for fine-tuning large language models by summarizing training trajectories of small models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 83465–83496. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Shen, Z.; Yue, Z.; Wu, Y.; Qin, B.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Tang, S.; Zhuang, Y. Mastering collaborative multi-modal data selection: A focus on informativeness, uniqueness, and representativeness. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.06293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, R.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, S.; Wang, P.; Bi, X.; et al. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.12948. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, W.; Yu, W.; Gu, X.; Wang, G.; Gan, G.; Tang, H.; Cheng, J.; Qi, J.; Ji, J.; Pan, L.; et al. Glm-4.1 v-thinking: Towards versatile multimodal reasoning with scalable reinforcement learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.01006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Bai, S.; Tan, S.; Wang, S.; Fan, Z.; Bai, J.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; et al. Qwen2-vl: Enhancing vision-language model’s perception of the world at any resolution. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.12191. [Google Scholar]

- Team, K.; Du, A.; Yin, B.; Xing, B.; Qu, B.; Wang, B.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Du, C.; Wei, C.; et al. Kimi-vl technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.07491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Yu, T.; Zhang, A.; Wang, C.; Cui, J.; Zhu, H.; Cai, T.; Li, H.; Zhao, W.; He, Z.; et al. Minicpm-v: A gpt-4v level mllm on your phone. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.01800. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, W.; Wang, W.; Ding, M.; Yu, W.; Lv, Q.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, S.; Ji, J.; Xue, Z.; et al. Cogvlm2: Visual language models for image and video understanding. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.16500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Fei, H.; Qu, L.; Ji, W.; Chua, T.S. Next-gpt: Any-to-any multimodal llm. In Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, S.; Fu, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, K.; Sun, X.; Xu, T.; Chen, E. A survey on multimodal large language models. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Wilson, C.; Dalins, J. Aligning Large Vision-Language Models by Deep Reinforcement Learning and Direct Preference Optimization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.06759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kordi, Y.; Mishra, S.; Liu, A.; Smith, N.A.; Khashabi, D.; Hajishirzi, H. Self-instruct: Aligning language models with self-generated instructions. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.10560. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Sun, Q.; Zheng, K.; Geng, X.; Zhao, P.; Feng, J.; Tao, C.; Lin, Q.; Jiang, D. WizardLM: Empowering large pre-trained language models to follow complex instructions. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Yu, B.; Hui, B.; Yu, H.; Huang, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, N.L. A preliminary study of the intrinsic relationship between complexity and alignment. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2308.05696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shengyu, Z.; Linfeng, D.; Xiaoya, L.; Sen, Z.; Xiaofei, S.; Shuhe, W.; Jiwei, L.; Hu, R.; Tianwei, Z.; Wu, F.; et al. Instruction tuning for large language models: A survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.10792. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; He, S.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Cheng, N.; Zhou, T. Superfiltering: Weak-to-strong data filtering for fast instruction-tuning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.00530. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Li, S.; Yan, J.; Wang, H.; Gunaratna, K.; Yadav, V.; Tang, Z.; Srinivasan, V.; Zhou, T.; Huang, H.; et al. Alpagasus: Training a better alpaca with fewer data. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.08701. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Lu, S.; Miao, C.; Bing, L. Mitigating object hallucinations in large vision-language models through visual contrastive decoding. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 13872–13882. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira e Silva, A.L.B.; de Castro Felix, H.; Simões, F.P.M.; Teichrieb, V.; dos Santos, M.; Santiago, H.; Sgotti, V.; Lott Neto, H. Insplad: A dataset and benchmark for power line asset inspection in uav images. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 44, 7294–7320. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, W. LoRa: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Lin, K.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Mm-vet: Evaluating large multimodal models for integrated capabilities. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.02490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Automation | Training-Free | API Independence | Clustering | Hallucination Mitigation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIMA | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × |

| Instruction Mining | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × |

| InstructionGPT-4 | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × |

| AlpaGasus | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Our Method | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| InsPLAD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | Precision | Recall | F1 |

| Base | 0.318 | 0.288 | 0.302 |

| Random_2000 | 0.530 | 0.510 | 0.520 |

| AlpaGasus_2000 | 0.617 | 0.570 | 0.592 |

| Choice_2000 | 0.700 | 0.678 | 0.689 |

| Random_3000 | 0.609 | 0.601 | 0.605 |

| AlpaGasus_3000 | 0.721 | 0.709 | 0.715 |

| Choice_3000 | 0.763 | 0.752 | 0.758 |

| Random_5000 | 0.736 | 0.724 | 0.730 |

| AlpaGasus_5000 | 0.747 | 0.728 | 0.738 |

| Choice_5000 | 0.815 | 0.803 | 0.809 |

| PowerQA | |||

| Methods | Cos | BLEU | GPTScore |

| Base | 0.0847 | 8.48 | 4.06 |

| Random_1500 | 0.1650 | 20.59 | 5.48 |

| AlpaGasus_1500 | 0.1673 | 20.59 | 5.43 |

| Choice_1500 | 0.1669 | 20.66 | 5.50 |

| Random_3000 | 0.1774 | 21.49 | 5.65 |

| AlpaGasus_3000 | 0.1817 | 21.72 | 5.69 |

| Choice_3000 | 0.1817 | 21.88 | 5.75 |

| Random_5000 | 0.1916 | 23.03 | 5.77 |

| AlpaGasus_5000 | 0.1920 | 23.12 | 5.85 |

| Choice_5000 | 0.1925 | 23.01 | 5.82 |

| Cos | BLEU | GPTScore | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cos | 0.1405 | 16.08 | 5.28 |

| BLEU | 0.1432 | 16.18 | 5.30 |

| GPTScore | 0.1781 | 21.71 | 5.65 |

| PPL | 0.1817 | 21.88 | 5.75 |

| class_num | Cos | BLEU | GPTScore |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1718 | 21.19 | 5.58 |

| 10 | 0.1817 | 21.88 | 5.75 |

| 30 | 0.1818 | 21.96 | 5.75 |

| 40 | 0.1810 | 21.69 | 5.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, H.; Shang, L.; Chen, X.; Feng, T.; Zhang, Y. Error-Guided Multimodal Sample Selection with Hallucination Suppression for LVLMs. Computers 2025, 14, 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120564

Cheng H, Shang L, Chen X, Feng T, Zhang Y. Error-Guided Multimodal Sample Selection with Hallucination Suppression for LVLMs. Computers. 2025; 14(12):564. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120564

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Huanyu, Linjiang Shang, Xikang Chen, Tao Feng, and Yin Zhang. 2025. "Error-Guided Multimodal Sample Selection with Hallucination Suppression for LVLMs" Computers 14, no. 12: 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120564

APA StyleCheng, H., Shang, L., Chen, X., Feng, T., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Error-Guided Multimodal Sample Selection with Hallucination Suppression for LVLMs. Computers, 14(12), 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120564