MT-TPPNet: Leveraging Decoupled Feature Learning for Generic and Real-Time Multi-Task Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a novel paradigm for the TPP task that integrates three sub-tasks into a single framework. This approach is particularly advantageous for multi-task scenarios requiring real-time processing, thereby enhancing the model’s deployability on edge devices such as onboard train computers.

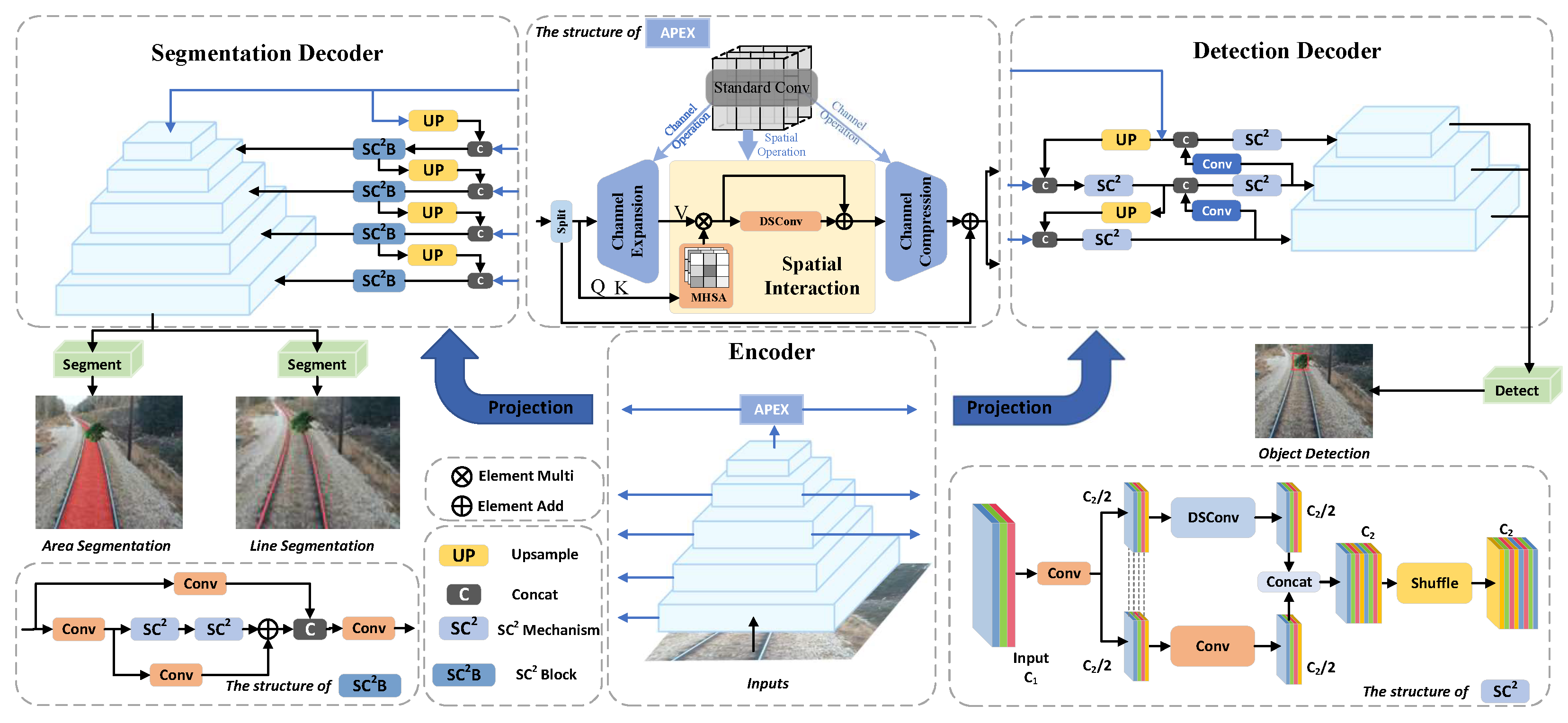

- By decoupling the processing along the spatial and channel dimensions, we propose the APEX and mechanisms. The former enables the encoder to simultaneously enhance the features of different decoders by leveraging attention operations with complementary inductive biases. The latter integrates high-frequency spatial details and low-frequency semantic relationships into the feature representations.

- Leveraging industrial-grade cameras and generative models, we constructed a dataset for the TPP task and manually annotated it. Extensive experiments on both the self-built and publicly available datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach.

2. Methodology

2.1. Encoder

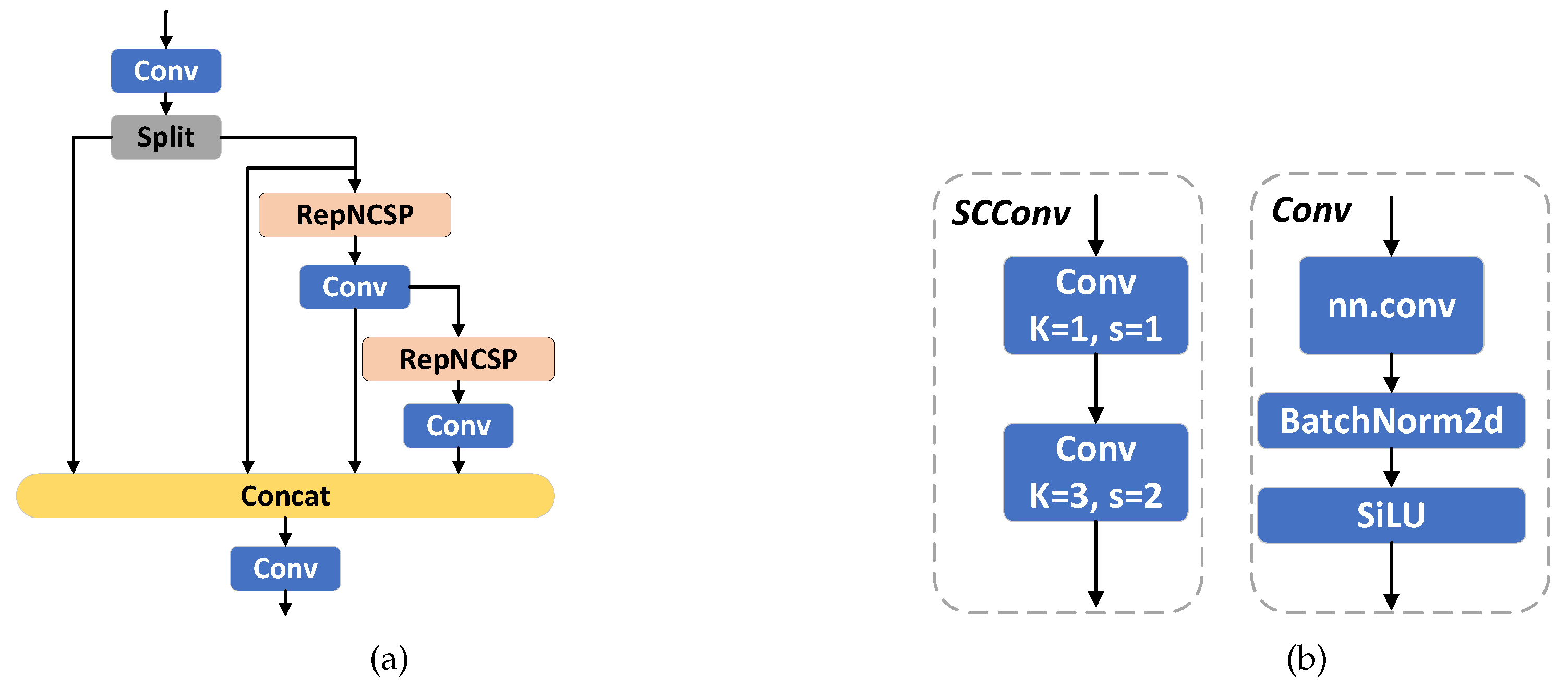

2.1.1. Backbone

2.1.2. APEX Mechanism

2.2. Decoder

2.2.1. Mechanism

2.2.2. Head

2.3. Loss Function

2.4. Training

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Experiment Details

3.1.1. Datasets

3.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

3.2. Experiment Results

3.2.1. Inference Speed

3.2.2. Multi-RID

3.2.3. BDD 100K

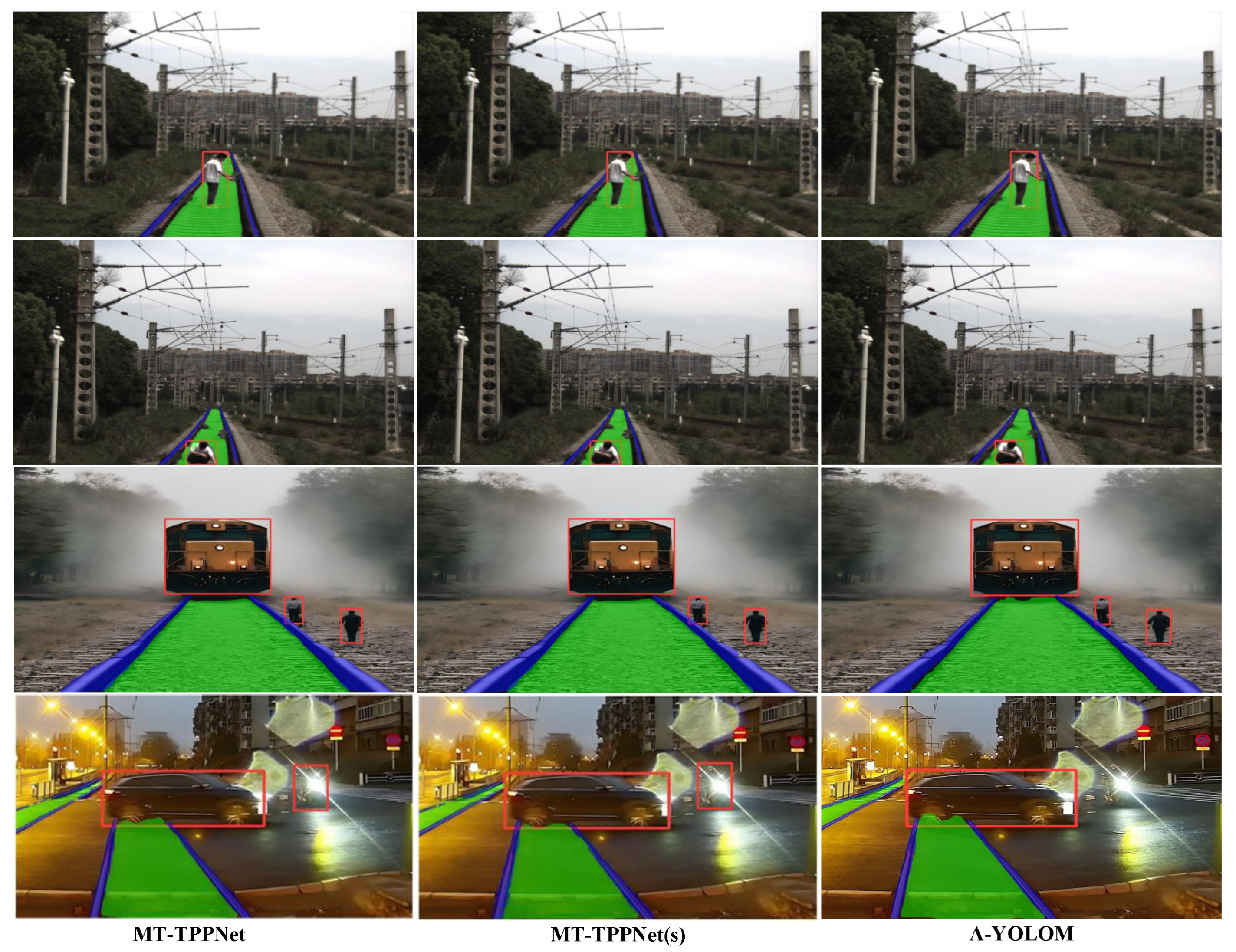

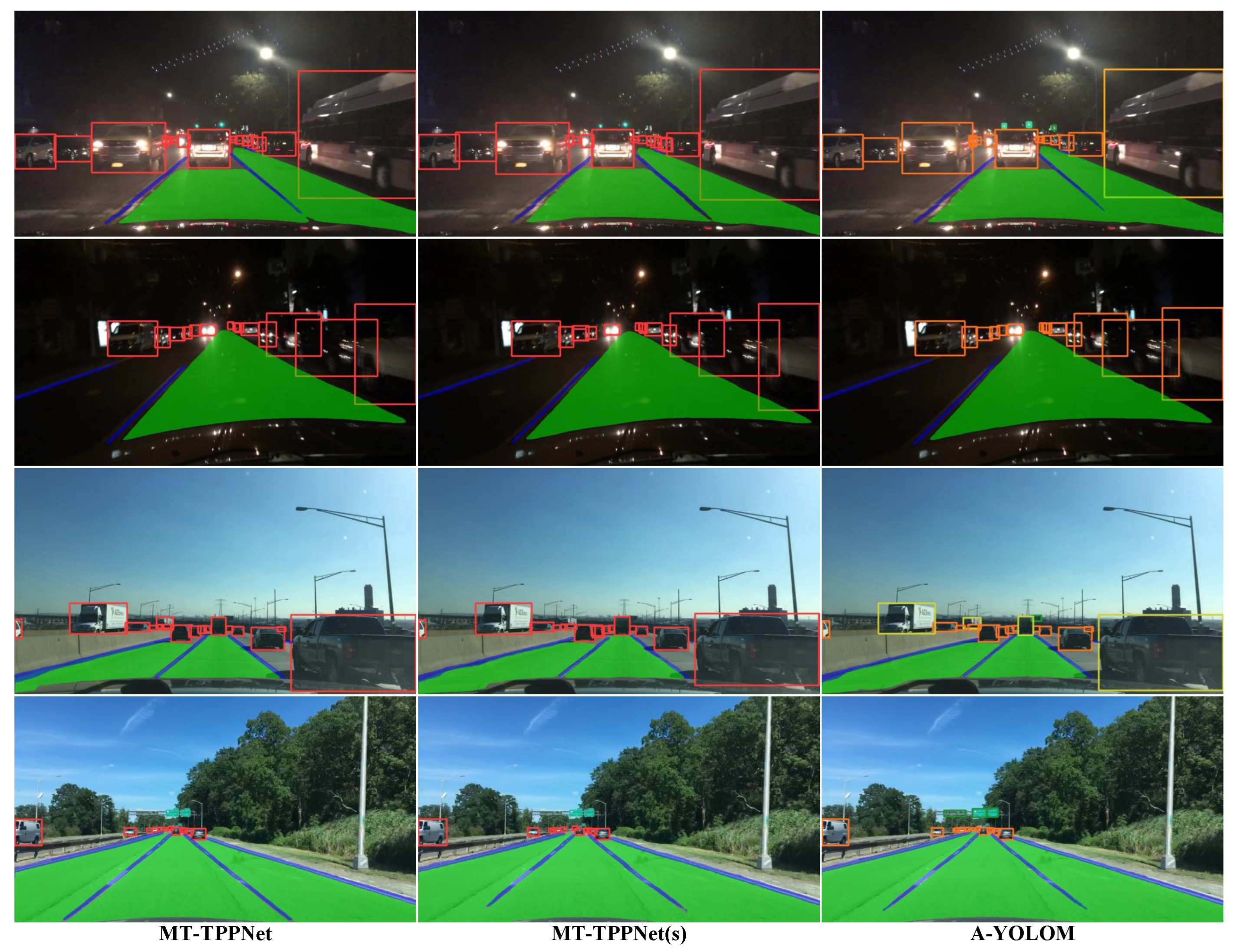

3.2.4. Visualization

3.3. Ablation Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gašparík, J.; Bulková, Z.; Dedík, M. Prediction of Transport Performance Development Due to the Impact of COVID-19 Measures in the Context of Sustainable Mobility in Railway Passenger Transport in the Slovak Republic. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopka, O.; Stopková, M.; Ližbetin, J.; Soviar, J.; Caban, J. Development Trends of Electric Vehicles in the Context of Road Passenger and Freight Transport. In Proceedings of the International Science-Technical Conference Automotive Safety, Kielce, Poland, 21–23 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, W.; Wang, J.; Lu, D.; Liu, J.; Cai, B. BDS for Railway Train Localization Test and Evaluation Using 3D Environmental Characteristics. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electromagnetics in Advanced Applications, Lisbon, Portugal, 2–6 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.W.; Qin, Y.; Jia, L.M.; Xie, Z.Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.G. Railway Intrusion Detection Based on Machine Vision: A Survey, Challenges, and Perspectives. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 6427–6448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.W.; Qin, Y.; Jia, L.M.; Xie, Z.Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.G. A systematic review of the literature on safety measures to prevent railway suicides and trespassing accidents. Accident. Anal. Prev. 2015, 81, 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Havârneanu, G.M.; Bonneau, M.H.; Colliard, J. Lessons learned from the collaborative European project RESTRAIL: REduction of suicides and trespasses on RAILway property. Eur. Transp. Rer. Rev. 2016, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Khattak, A.J.; Clarke, D. Non-crossing rail-trespassing crashes in the past decade: A spatial approach to analyzing injury severity. Safety. Sci. 2016, 82, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.L.; Li, J.; Wei, H.B.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Z.F.; Ren, Q.L. Slim-neck by GSConv: A lightweight-design for real-time detector architectures. J. Real-Time Image Pr. 2024, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.N.; Li, X.T.; Li, J.; Liang, L. Rethinking Mobile Block for Efficient Attention-based Models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.Q.; He, K.M.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable Bag-of-Freebies Sets New State-of-the-Art for Real-Time Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–20 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.H.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.J.; Han, J.G.; Din, G.G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Chaurasia, A.; Kim, S.; Culurciello, E. Enet: A deep neural network architecture for real-time semantic segmentation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.02147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.S.; Shi, J.P.; Qi, X.J.; Wang, X.G.; Jia, J.Y. Pyramid Scene Parsing Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.G.; Shi, J.P.; Luo, P.; Wang, X.G.; Tang, X.O. Spatial as Deep: Spatial CNN for Traffic Scene Understanding. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.N.; Ma, Z.; Liu, C.X.; Loy, C.C. Learning Lightweight Lane Detection CNNs by Self Attention Distillation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Y.; Wu, Q.M.J.; Zhang, N. You Only Look at Once for Real-Time and Generic Multi-Task. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 12625–12637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Liao, M.W.; Zhang, W.T.; Wang, X.G. Yolop: You only look once for panoptic driving perception. Mach. Intell. Res. 2022, 19, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichmann, M.; Weber, M.; Zöllner, M.; Cipolla, R.; Urtasun, R. MultiNet: Real-time Joint Semantic Reasoning for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, New York, NY, USA, 26–30 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.M.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.F.; Tao, D.C. Vision Transformer With Quadrangle Attention. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 3608–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grainger, R.; Paniagua, T.; Song, X.; Cuntoor, N.; Lee, M.W.; Wu, T.F. PaCa-ViT: Learning Patch-to-Cluster Attention in Vision Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, X.J.; Ke, Z.H.; Zhang, W.Y.; Lau, R. BiFormer: Vision Transformer with Bi-Level Routing Attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.H.; Wu, L.J.; Chen, S.; Hu, X.L.; Li, J.; Tang, J.H.; Yang, J. Generalized focal loss: Learning qualified and distributed bounding boxes for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–12 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.H.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.Z.; Ye, R.G.; Ren, D.W. Distance-IoU loss: Faster and better learning for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, S.S.M.; Erdogmus, D.; Gholipour, A. Tversky Loss Function for Image Segmentation Using 3D Fully Convolutional Deep Networks. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Machine Learning in Medical Imaging, Quebec, ON, Canada, 10 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Podell, D.; English, Z.; Lacey, K.; Blattmann, A.; Dockhorn, T.; Müller, J.; Penna, J.; Rombach, R. SDXL: Improving Latent Diffusion Models for High-Resolution Image Synthesis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Y.Q.; Dolan, J.; Yang, M. DLT-Net: Joint Detection of Drivable Areas, Lane Lines, and Traffic Objects. IEEE T. Intell. Transp. 2019, 21, 4670–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Parameters | FPS (ba = 16) |

|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8s(seg) | 11.79 M | 256 |

| YOLOv8s(det) | 11.13 M | 277 |

| A-YOLOM(s) [18] | 13.6 M | 298 |

| MT-TPPNet(s) | 3.71 M | 322 |

| MT-TPPNet | 13.83 M | 285 |

| Model | Intrusion Object Detection | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Recall (%) | mAP50 (%) | |

| YOLOv8s(det) | 11.13 M | 82.1 | 67.7 |

| YOLOv8n(det) | 3.01 M | 80.9 | 66.3 |

| YOLOv9(m) [11] | 20.0 M | 80.5 | 69.7 |

| YOLOv10(m) [13] | 16.49 M | 82.5 | 71.6 |

| MultiNet [20] | N/A | 78.3 | 70.1 |

| YOLOP [19] | 7.9 M | 80.6 | 69.7 |

| A-YOLOM(n) [18] | 4.43 M | 82.4 | 65.0 |

| A-YOLOM(s) [18] | 13.61 M | 78.4 | 69.4 |

| MT-TPPNet(s) | 3.71 M | 81.8 | 70.2 |

| MT-TPPNet | 13.83 M | 83.7 | 72.4 |

| Model | Area | Track-Line | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mIoU (%) | Accuracy (%) | IoU (%) | |

| YOLOv8s(seg) | 92.7 | 87.5 | 58.2 |

| SCNN [16] | N/A | N/A | 62.1 |

| PSPNet [15] | 90.6 | N/A | N/A |

| YOLOP [19] | 92.7 | 87.8 | 68.2 |

| MultiNet [20] | 91.1 | N/A | N/A |

| A-YOLOM(n) [18] | 92.4 | 88.4 | 67.4 |

| A-YOLOM(s) [18] | 92.9 | 88.2 | 68.0 |

| MT-TPPNet(s) | 93.1 | 88.7 | 68.1 |

| MT-TPPNet | 93.4 | 88.9 | 68.8 |

| Model | Traffic Object Detection | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Recall | mAP50 | |

| YOLOv8(n) (det) | 3.01 M | 82.2 | 75.1 |

| YOLOv10(m) [13] | 16.49 M | 72.5 | 81.8 |

| YOLOP [19] | 7.9 M | 88.6 | 76.5 |

| MultiNet [20] | N/A | 81.3 | 60.2 |

| DLT-Net [30] | N/A | 89.3 | 68.4 |

| A-YOLOM(n) [18] | 4.43 M | 85.3 | 78.0 |

| A-YOLOM(s) [18] | 13.61 M | 86.9 | 81.1 |

| MT-TPPNet(s) | 3.71 M | 83.1 | 76.8 |

| MT-TPPNet | 13.83 M | 89.4 | 83.2 |

| Model | Area | Lane Line | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mIoU | Accuracy (%) | IoU (%) | |

| SCNN [16] | N/A | N/A | 15.84 |

| YOLOv8n(seg) | 78.1 | 80.5 | 22.9 |

| PSPNet [15] | 89.6 | N/A | N/A |

| MultiNet [20] | 71.6 | N/A | N/A |

| A-YOLOM(n) [18] | 90.5 | 81.3 | 28.2 |

| A-YOLOM(s) [18] | 91.0 | 84.9 | 28.8 |

| YOLOP [19] | 91.2 | 84.2 | 26.5 |

| MT-TPPNet(s) | 89.8 | 84.8 | 28.8 |

| MT-TPPNet | 91.6 | 85.1 | 28.9 |

| Model | APEX | Parameters | Recall (%) | mAP50 (%) | mIoU (%) | Acc (%) | IoU (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT-TPPNet(s) | - | - | 3.55 M | 78.1 | 67.6 | 92.1 | 87.7 | 67.2 |

| ✓ | - | 3.87 M | 79.6 | 68.3 | 92.6 | 88.2 | 67.9 | |

| - | ✓ | 3.39 M | 78.4 | 67.8 | 92.2 | 88.2 | 67.7 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | 3.71 M | 81.8 | 70.2 | 93.1 | 88.7 | 68.1 | |

| MT-TPPNet | - | - | 13.27 M | 82.5 | 71.1 | 92.6 | 88.1 | 67.7 |

| ✓ | - | 14.53 M | 83.6 | 72.3 | 93.2 | 88.8 | 68.6 | |

| - | ✓ | 12.57 M | 83.0 | 71.9 | 93.1 | 88.2 | 68.1 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | 13.83 M | 83.7 | 72.4 | 93.4 | 88.9 | 68.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, X.; Luo, C.; Xia, Y.; Wei, X. MT-TPPNet: Leveraging Decoupled Feature Learning for Generic and Real-Time Multi-Task Network. Computers 2025, 14, 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120536

Tang X, Luo C, Xia Y, Wei X. MT-TPPNet: Leveraging Decoupled Feature Learning for Generic and Real-Time Multi-Task Network. Computers. 2025; 14(12):536. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120536

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Xiaokun, Chunlin Luo, Yuting Xia, and Xiaohua Wei. 2025. "MT-TPPNet: Leveraging Decoupled Feature Learning for Generic and Real-Time Multi-Task Network" Computers 14, no. 12: 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120536

APA StyleTang, X., Luo, C., Xia, Y., & Wei, X. (2025). MT-TPPNet: Leveraging Decoupled Feature Learning for Generic and Real-Time Multi-Task Network. Computers, 14(12), 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120536