1. Introduction

Anti-tank landmines, particularly TM-62, remain a major obstacle to safe post-conflict recovery, delaying land release, agriculture, and infrastructure repair [

1]. Low-altitude UAV imaging offers scalable coverage at a modest cost, yet the visual signature of surface or shallow-buried landmines is subtle and easily masked by soil texture and vegetation (see

Figure 1). Our goal in this paper is the reliable, real-time detection of TM-62 landmines in UAV and ground-level RGB imagery, with results being reported both by standard COCO metrics and an explicit operating point relevant to field triage [

2].

Visual and statistical properties of the target class make this problem unusually demanding [

3]. Landmines occupy only a few pixels at survey altitudes, frequently appearing under partial occlusion or camouflage, and are often recorded under variable illumination and viewing angles [

4]. These factors decrease recall for single-scale detectors and interact with class imbalance, since positives are scarce relative to background patterns that resemble circular or metallic textures [

5]. Practical workflows, therefore, require not only aggregate mAP but also a clearly stated operating point that trades precision and recall without inflating false alarms [

6].

This research study extends our previous UAV-based UXO detection pipeline while keeping the training environment constant—identical hardware and software (Python 3.11, PyTorch 2.7.1, CUDA 12.9.1, cuDNN kept fixed across runs) are used to isolate methodological and data effects [

2]. The present study introduces a new, single-class TM-62 dataset comprising 4289 high-resolution RGB images captured both from a UAV and from the ground, with 468 images reserved for validation and 233 for a held-out test set. In contrast to our earlier study [

2], a different UAV platform and camera are employed, tuned to low-altitude mapping. Methodologically, we integrate YOLOv5 with Slicing Aided Hyper Inference (SAHI) tiling to expose few-pixel targets at a workable scale and Weighted Boxes Fusion to consolidate overlapping tile predictions [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

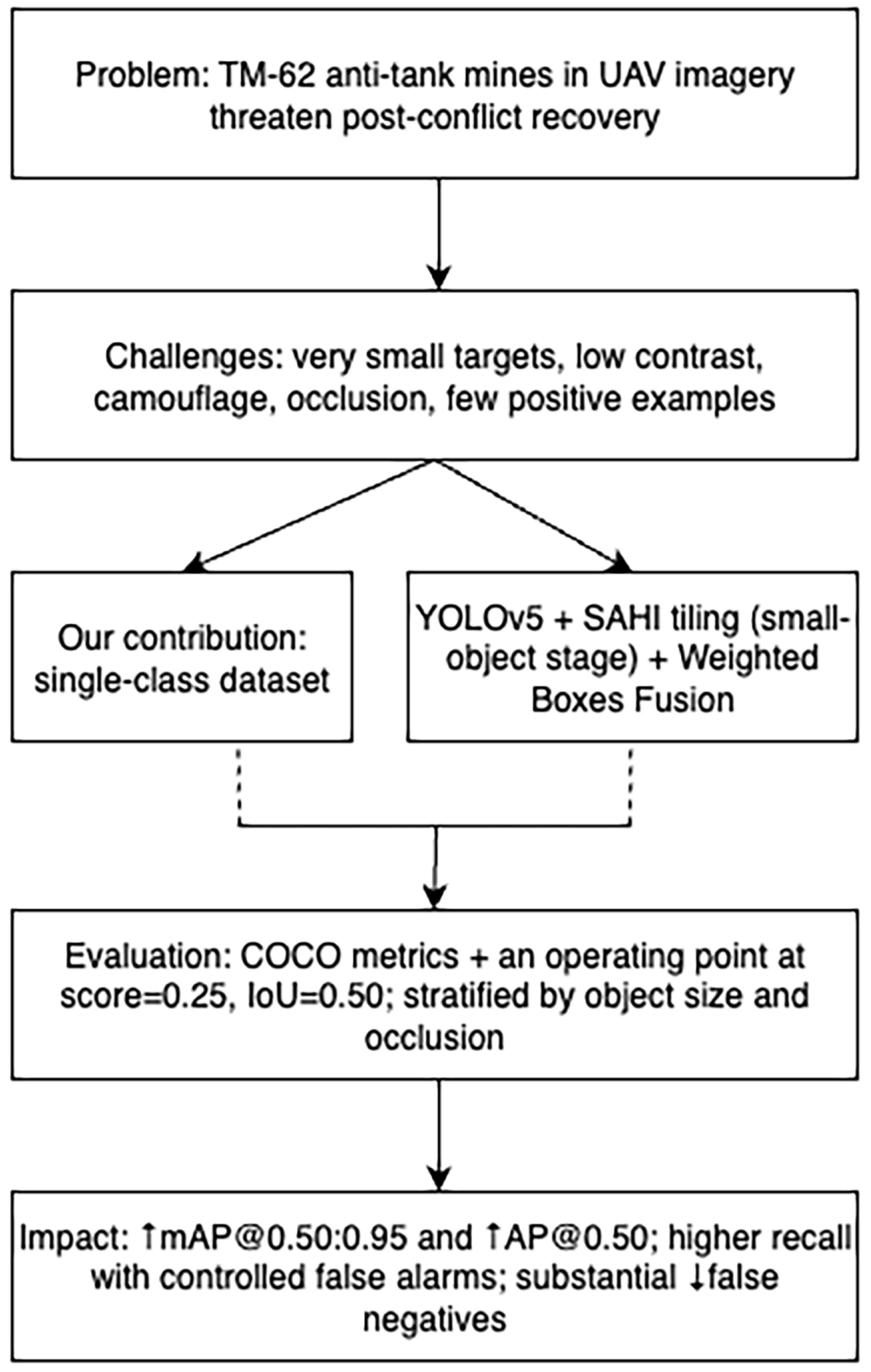

Figure 2 summarizes the narrative of this paper. The upper blocks state the application problem and the visual challenges typical of UAV scenes. The center blocks mark the two contributions: a dedicated single-class TM-62 dataset and a detector that couples YOLOv5 with a small-object stage based on SAHI plus Weighted Boxes Fusion for stable mosaicking. The lower blocks preview the evaluation protocol—COCO mAP@0.50:0.95 and AP@0.50 together with an operating point at score = 0.25 and IoU = 0.50, stratified by object size and occlusion—and the intended impact: higher recall at controlled false-alarm rates with markedly fewer misses [

12].

This study addresses gaps common in the literature: surface and camouflaged targets are underrepresented, results are often reported only as aggregate mAP, and operating points relevant to field decision making are seldom specified [

13]. By combining the new dataset with a small-object-aware inference stage and rigorous reporting at a fixed operating point, we align evaluation with operational use [

14]. On the held-out test partition, a baseline YOLOv5 configuration attains mAP@0.50:0.95 = 0.553 and AP@0.50 = 0.851 [

15,

16,

17,

18]. With tuned SAHI (768 px tiles, 40% overlap) and fusion, performance rises to 0.685 and 0.935 [

19,

20]. At the operating point, the pipeline achieves precision = 0.94 and recall = 0.89 (F1 = 0.914), implying a 58.4% reduction in missed detections relative to baseline YOLOv5 (no SAHI tiling) and a +14.3 AP@0.50 gain on the small/occluded subset [

21,

22].

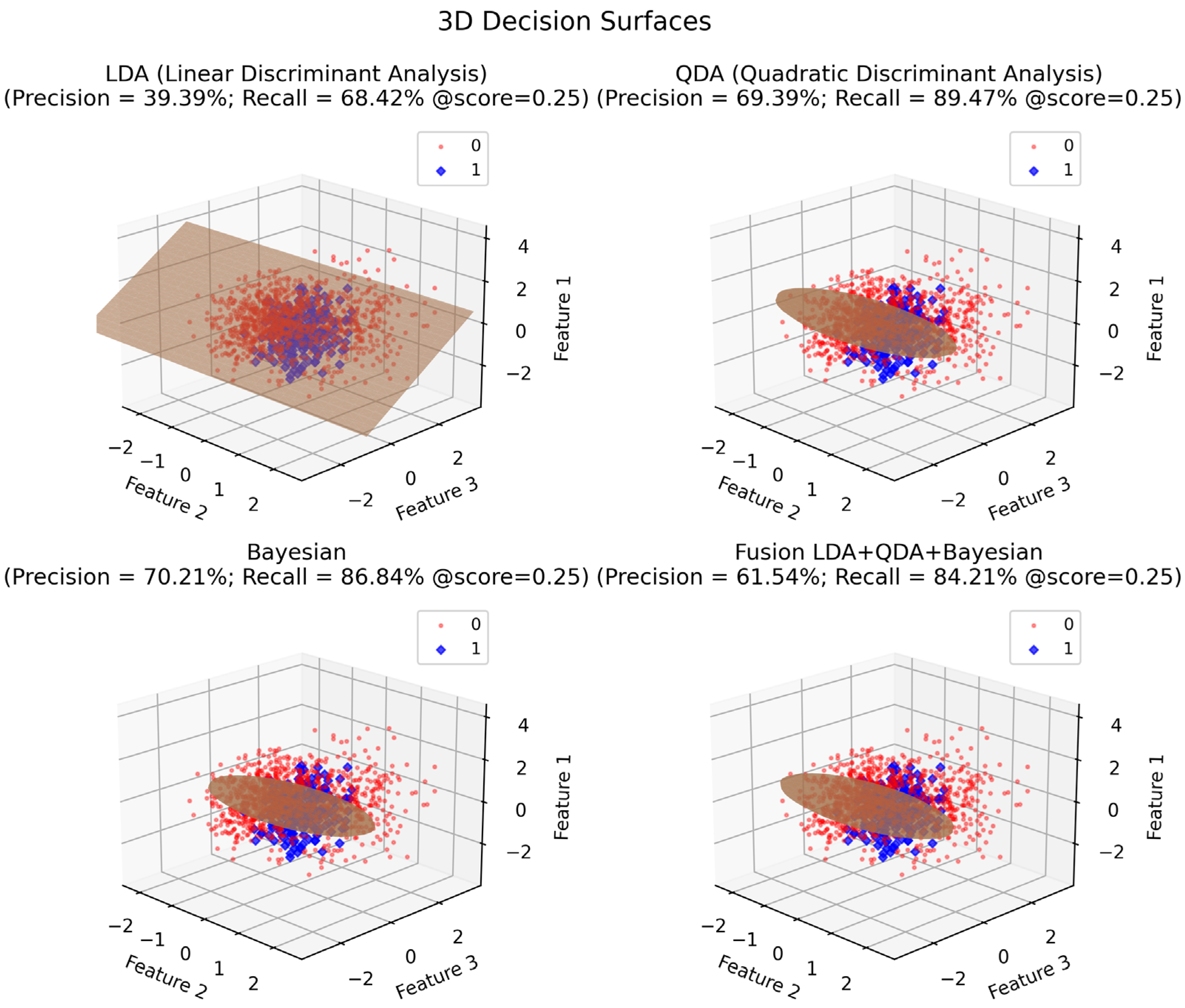

To build intuition for why scale and occlusion control detector behavior, we accompany the textual argument with a compact visualization of decision boundaries [

23].

Figure 3 provides a geometric view of class separability under varying model assumptions and effective scale, reinforcing the motivation for a small-object stage and for reporting performance at a fixed operating point [

24].

Data curation, the SAHI-enhanced YOLOv5 with Weighted Boxes Fusion, and the evaluation protocol provide a coherent path from the visual challenges of the landmine-action domain to measurable gains in recall without unacceptable growth in false positives.

Recent operational reports describe pipelines that process drone imagery for landmine/UXO detection (RGB and multisensor). In parallel, optical–magnetometric UAV surveys (e.g., fluxgate sweeps) are used to capture subsurface anomalies. These system-level accounts are orthogonal to our technical focus (SAHI + WBF), but they motivate our OP-based evaluation under a precision constraint and clarify scope: our RGB-only pipeline targets small, partially occluded surface or shallow-buried signatures where visual cues exist, whereas magnetometric modalities address deeper or non-visible cases. We therefore position our results as complementary to optical–magnetometric pipelines and discuss generalization and fusion prospects in

Section 5.7 and

Section 5.8.

The manuscript follows the journal format: Introduction; Related Work/SoTA (small-object aerial detectors, including YOLOv7/YOLOv8/RT-DETR families, and optical–magnetometric pipelines and datasets); Materials and Methods (dataset, acquisition geometry, model/training, SAHI/WBF, evaluation protocol); Results (COCO and OP metrics, ablations, sensitivity); Discussion (operational interpretation, robustness, throughput); Limitations and Outlook (domain shift, RGB–thermal fusion, multi-backbone benchmarking plan); Data/Code Availability and Ethics; and Conclusions [

25].

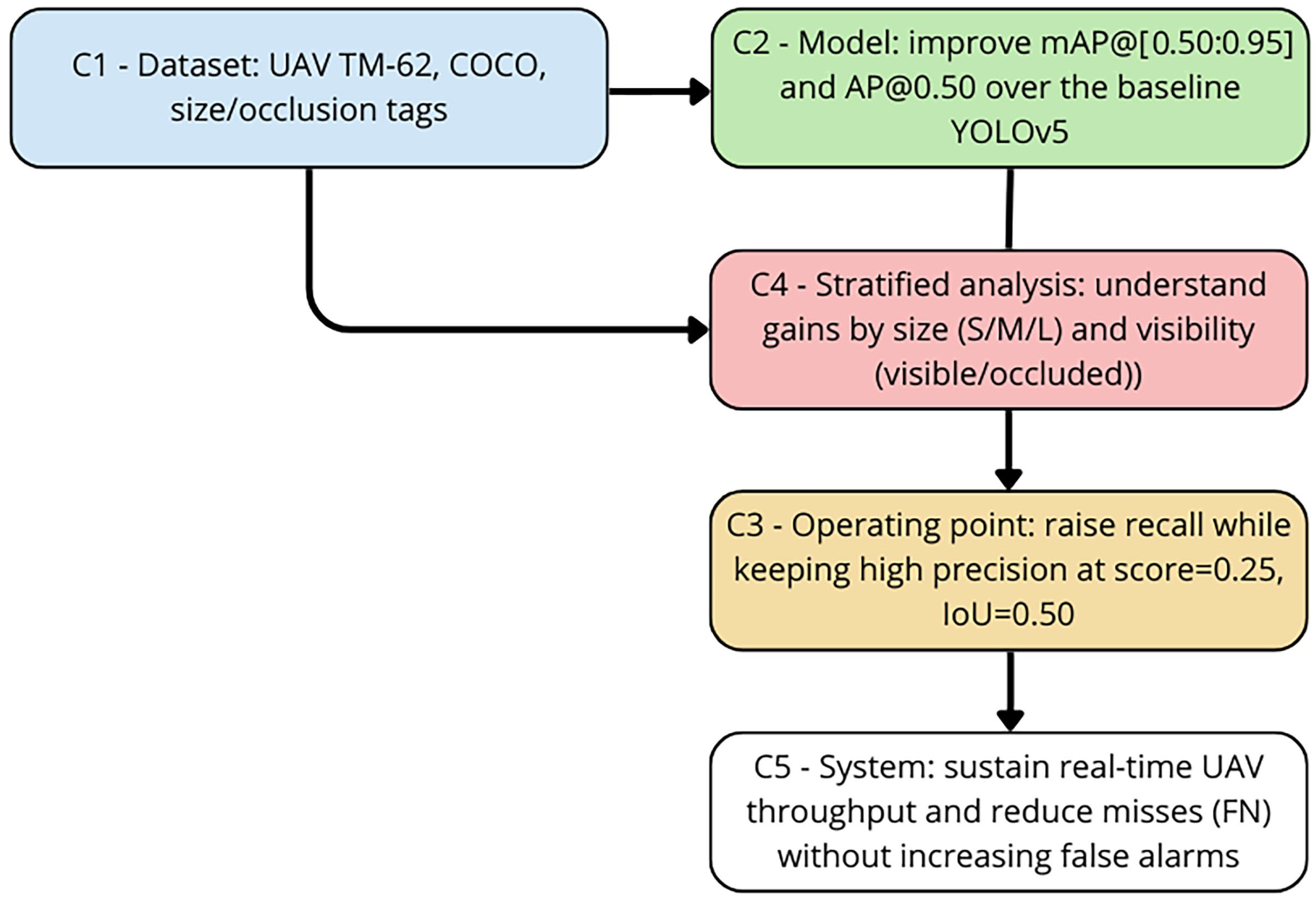

3. From Sensor Geometry to Real-Time Detection

This section integrates a theoretical layer (imaging geometry and box-fusion analytics) with an experimental layer (dataset, training, SAHI inference, and OP-based evaluation) to obtain reproducible and operationally useful results for detecting TM-62 landmines in UAV RGB imagery. All design choices follow Objectives C1–C5 and are consistently assessed at a fixed operating point (OP; score = 0.25, IoU = 0.50) under a precision floor

= 0.90. In addition, we report OP-sensitivity (±0.05 in score/IoU), a full ablation grid over tile size/overlap and suppression method (NMS, Soft-NMS, WBF) with 95% bootstrap CIs and paired Wilcoxon tests, a latency distribution (per-image percentiles), and a structured failure analysis; we also articulate threats to validity

and restricted data/code availability consistent with dual-use considerations [

2,

26,

28,

29,

32,

36,

37,

39]. An overview of the processing pipeline is shown in

Figure 7.

The diagram summarizes the end-to-end flow and how each block supports the objectives. SAHI produces overlapping tiles (~768 px, ~40% overlap) to expose few-pixel and partially occluded TM-62 instances; detections are mapped back and fused via WBF to remove border duplicates while preserving true positives. We then apply the OP filter (score = 0.25, IoU = 0.50) under

= 0.90 and compute P, R,

, TP/FP/FN, AP@0.50, and mAP@0.50:0.95. Beyond this baseline pipeline,

Section 3.9 details a controlled ablation grid (tile × overlap × suppression),

Section 3.10 quantifies OP sensitivity,

Section 3.11 reports latency distributions, and

Section 3.8 provides a failure typology that links error modes to tiling and fusion choices [

26,

32,

36,

37,

39].

3.1. Dataset and Annotation (C1)

We curated a single-class TM-62 dataset (4289 HR RGB images) with a train/val/test split (468/-/233). For OP-based counts aligned with the FN bar chart, we use

= 308 test boxes (77 to 32; −58.4%). COCO-style axis-aligned boxes underwent a two-pass QA with corrections prior to training/evaluation and location-based splits to prevent scene leakage. Threats to validity include site/season bias, annotation noise, and look-alike distractors (e.g., stones/metal). To mitigate these, we stratify by size/occlusion, reserve cross-location folds (

Section 3.7 and

Section 3.9), and run per-image bootstrap for CIs. Given dual-use risks and sensitive geospatial context, we disclose full configs and evaluation protocols, whereas raw images, labels, and internal code are not publicly released (

Section 3.12) [

2,

26,

41].

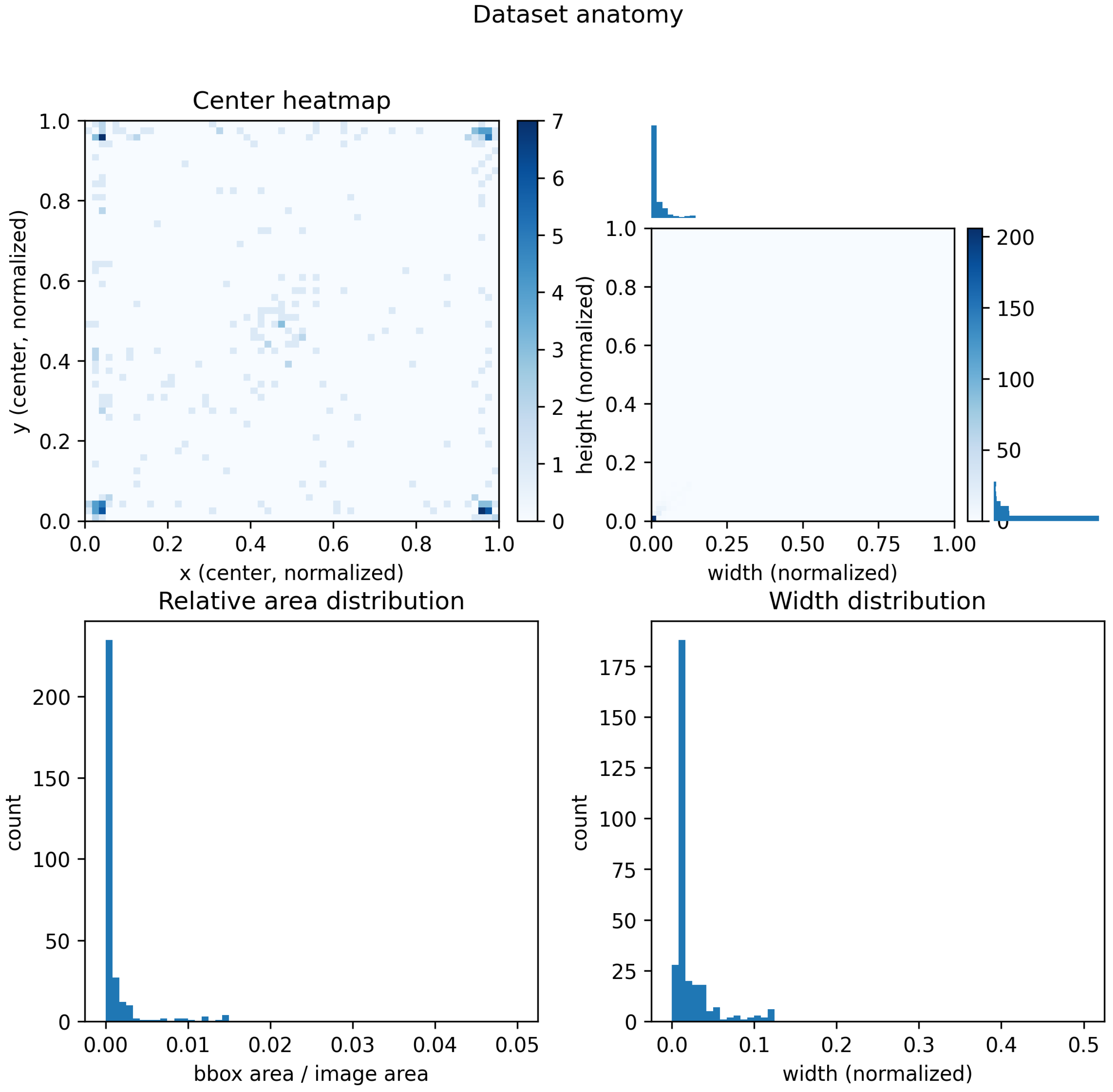

The 2D center heatmap shows broad spatial coverage with no positional bias, justifying uniform tiling rather than heuristic regions of interest. The width–height joint histogram (with marginals) and relative area distribution confirm a small-object regime: most instances occupy <1% of the image area and exhibit narrow normalized dimensions. These statistics motivate SAHI tiling to increase the effective scale and support the OP choice (IoU = 0.50), which is robust to annotation granularity and partial occlusion [

37,

39].

On the held-out test split (233 images;

boxes), this corresponds to 1.32 positives per image on average; instances are predominantly small and often partially occluded (see

Figure 8). Acquisition uses a DJI Mavic 3 (DJI, Shenzhen, China) at 8 m AGL (RGB; GSD ≈ 2.18 mm/px). These properties justify evaluation at IoU = 0.50 and reporting at a fixed operating point.

We summarize dataset anatomy concisely: On the test split (233 images;

), we have ≈1.32 positives per image on average. Most instances occupy <1% of the image area (

Figure 8) and are frequently partially occluded. Acquisition covers grassland/tracks under daytime illumination at 8 m AGL (RGB, DJI Mavic 3, GSD ≈ 2.18 mm/px). In detection, the negative class is background, and TNs are not enumerated. Accordingly, we report FP counts and OP feasibility rather than “positive/negative ratios.” The dataset itself is not public due to dual-use safeguards; instead, we fully state all parameter values, OP definitions, and the evaluation protocol within the manuscript, enabling procedural replication on independent, non-sensitive data.

3.2. Imaging Geometry and Effective Scale (Theoretical Foundation)

Let

and

denote sensor width/height,

f the effective focal length,

H the flight altitude, and

imW ×

imH the image resolution. The ground sampling distance (GSD) along each axis is

For a circular target of physical diameter D (TM-62 ≈ 0.32 m), the expected pixel diameter on the image is

As referenced below,

Table 3 lists the imaging parameters and derived quantities (sensor size, image resolution, focal length, flight altitude, GSD, and expected pixel diameter) used in

Section 3.2 and later in

Figure 6. Acquisition and optics parameters used in the calculations are summarized in

Table 3.

Equations (3) and (4) quantify the effective scale at which the detector “sees” the landmine. With

H = 8 m, the landmine spans ~147 px, large enough for YOLOv5’s receptive fields/anchors, yet still small relative to the full frame, so down-scaling would erase detail. This analysis directly justifies the tile size of 768 px: it keeps the object well resolved, maintains contextual support around it, and—when combined with ~40% overlap—prevents clipping and improves robustness to occlusion. These values, in turn, determine how many tiles per image must be processed (C5) [

37,

39].

Typical flight speeds were kept low to bound motion blur at the reported GSD. Exposure settings (shutter/ISO) favored short integrations to preserve edge contrast, with gimbal stabilization limiting yaw/pitch/roll excursions. Rolling shutter and exposure drift across mosaics were monitored qualitatively. Residual blur behaves similarly to occlusion in our failure modes (

Section 3.8) and is covered by the OP protocol rather than separate stress plots.

3.3. Model, Training, SAHI Inference, and Box Fusion (C2 and C4)

We use YOLOv5 configured for a single “TM-62” class and trained/evaluated with COCO metrics (mAP@0.50:0.95 and AP@0.50). Stratified reporting (small/medium; visible/occluded) is used to avoid global averages masking hard cases (C4).

We fix YOLOv5 to isolate the contribution of SAHI (small-object exposure) and WBF (hypothesis consolidation) under identical seeds/hyperparameters and a single-GPU 8 GB envelope. This removes architecture drift and keeps throughput accounting comparable while we ablate tile size, overlap, and fusion—the core levers of this research study. To show that conclusions are not backbone-idiosyncratic, we also include a compact modern control (YOLOv8, same split and OP;

Section 4.5). Importantly, SAHI and WBF are detector-agnostic: the identical tiling and fusion stages can be attached to YOLOv7/8, RetinaNet, and DETR/RT-DETR families without changing the OP protocol or the IPS budget. A broader multi-backbone benchmark (including RT-DETR variants) is deliberately deferred to follow-up work under the same OP/IPS constraints to preserve fairness and scope.

During inference, images are sliced into tiles of 768 px with ~40% overlap. Tile predictions are projected back to the global image coordinates using the known tile offsets; overlap ensures that marginal objects are seen at least once at a favorable position and scale.

Overlapping boxes are merged as a confidence-weighted barycenter:

where

denotes normalized coordinates,

denotes detector confidences, and

denotes optional source weights (e.g., per-tile reliability). We set

= 0.50 to align with the OP. Unlike (Soft-)NMS, which discards or decays boxes, WBF preserves evidence from multiple tiles, reduces coordinate variance at seams, and typically increases recall without inflating FPs [

26,

32,

36,

37]. A compact worked example is provided in

Table 4.

The fused box lies closer to

(higher confidence) yet remains within the geometric overlap enforced by

. In our SAHI setup, many objects appear in multiple tiles; WBF consolidates them into a single, stable global detection, eliminating double counts and preventing false alarms from border jitter [

36,

37,

39].

SAHI (small-object exposure) and WBF (hypothesis consolidation) are architecture-agnostic and can also be applied to YOLOv8/RetinaNet/DETR-like frameworks. In this study, we intentionally fix YOLOv5 to isolate the impact of tiling/fusion under the same seed, hyperparameters, and throughput accounting, leaving multi-backbone benchmarking outside the scope.

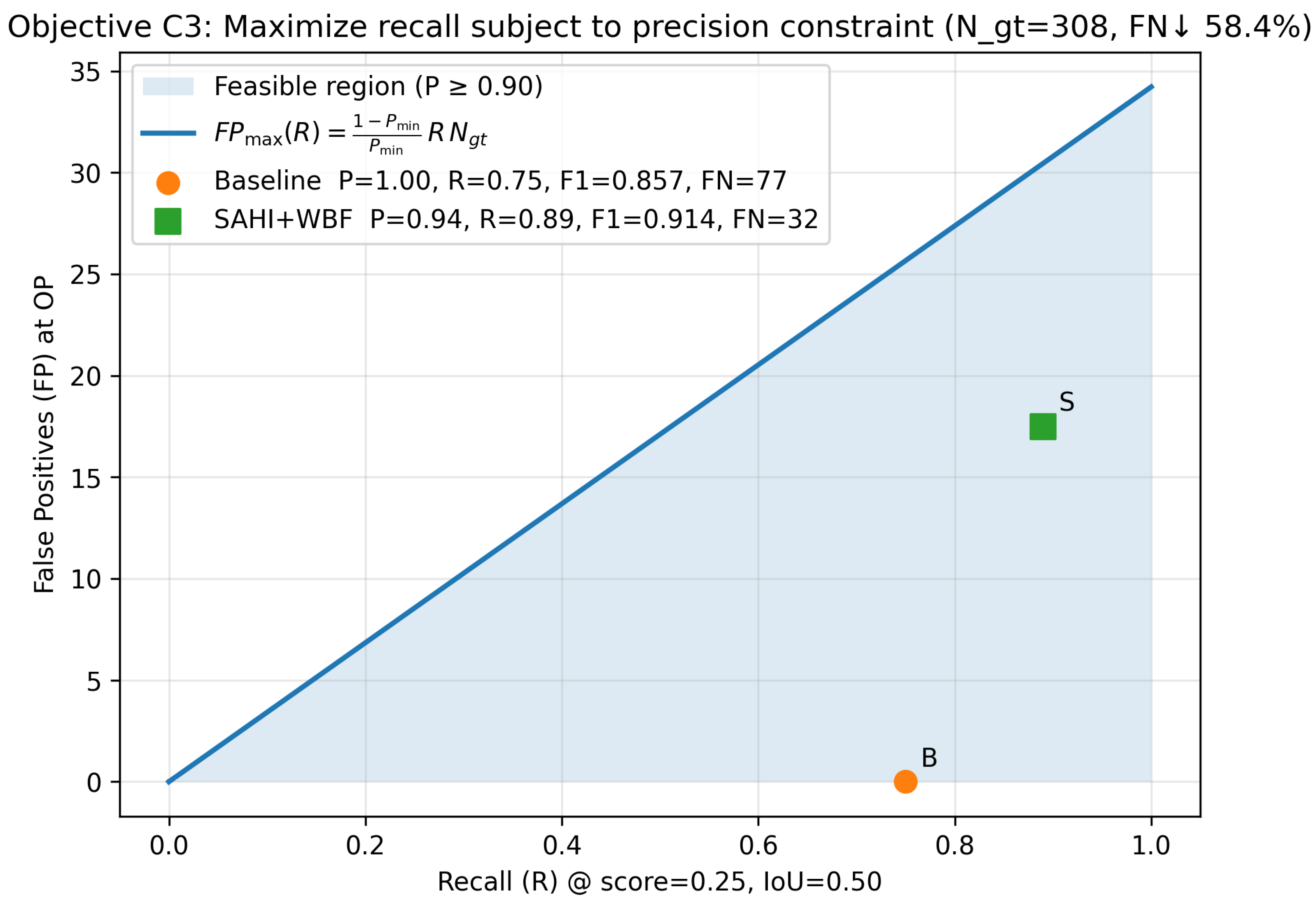

3.4. Operating Point and Evaluation Protocol (C3)

We report deployment-facing metrics at a fixed operating point to reflect field triage: detections are thresholded by score under a minimum precision constraint

, and matches are evaluated at IoU = 0.50. The precision threshold and the recall objective formally define a feasible region in

(Equation (1)), which we use to verify admissibility of the operating point and to compute FN/FP budgets. IoU = 0.50 is chosen deliberately for partially occluded and annotation-granularity-limited targets, where tighter IoUs overweight boundary ambiguity and vegetation-covered rims; our dataset analysis (

Figure 8) confirms a small-object, occlusion-prone regime where IoU = 0.50 is standard and robust.

is the verified ground-truth box count on the held-out test split (233 images) after QC, used consistently for OP feasibility and FN accounting. Equations (1) and (2) were re-derived and numerically checked against the reported

FP budget and measured IPS rate, ensuring consistency between the analytical bounds and the empirical setup. Per-method operating-point metrics are summarized in

Table 1. The tiles-per-image mapping and corresponding throughput are reported in

Table 2 (see also

Figure 6).

The score threshold is selected on the validation set by sweeping the PR curve and choosing the lowest score such that precision ≥ (tie breaking by maximal ); the resulting value (≈0.25) is then fixed and carried over to the test set to avoid bias. We further report sensitivity around this nominal OP (score ∈ [0.20, 0.30], IoU ∈ {0.50, 0.55, 0.60, 0.75}) to show that conclusions are not artifacts of a particular threshold.

Unless noted, all OP numbers use score 0.25/IoU 0.50/

as per the

Section 3.4 reference definition.

We report P, R, , TPs, FPs, and FNs at the OP alongside and . Results are stratified by object size (small/medium) and visibility (visible/occluded), highlighting where SAHI brings measurable gains.

For reliability of differences (no-SAHI vs. SAHI; NMS vs. WBF), we apply per-image bootstrap (

n = 1000) to derive 95% CIs for ΔAP@0.50 and ΔRecall@OP, and a paired Wilcoxon test over per-image metrics. We report medians with CIs rather than only

p-values [

26,

28,

29,

32,

36].

IoU = 0.50 is chosen for partially occluded, small, annotation-granularity-limited targets. Tighter IoUs overweight boundary ambiguity and vegetation-covered rims (cf. size/occlusion stats and

Figure 8). The precision threshold

encodes the field triage requirement that recall gains must not inflate false alarms. Equation (1) gives the admissible FP budget as a function of recall and

, which matches our OP FN accounting.

The score = 0.25 OP is selected on the validation set by sweeping PR and taking the lowest score with precision ≥

(tie breaking at max

) and is then frozen for testing in order to avoid bias. Robustness is confirmed by OP sensitivity (score ∈ [0.20, 0.30], IoU ∈ {0.50, 0.55, 0.60, 0.75} in

Section 3.10), while PR-AUC/ROC-AUC (summarized in

Section 4.1) and mAR (AR@{1,10,100}) track the same trend, indicating that conclusions are not artifacts of a single threshold.

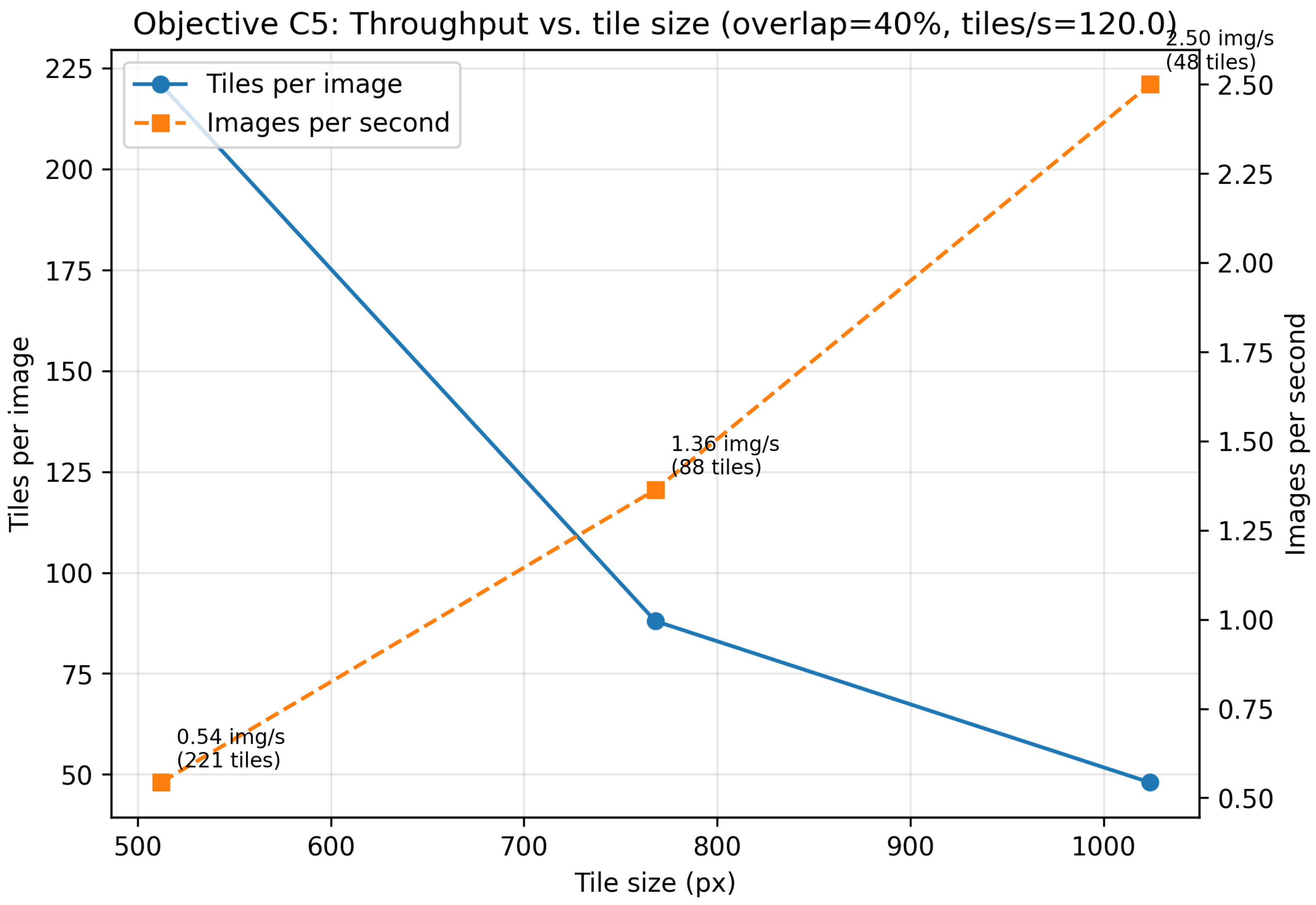

3.5. Real-Time Considerations and System Sustainability (C5)

SAHI increases the number of tiles per image; throughput, therefore, depends on tile geometry and the measured tile rate. With our configuration (tile = 768 px, overlap ≈ 40%) and processing rate (120 tiles/s), the system achieves 1.36 images/s with 88 tiles/image, striking a good accuracy/IPS balance. Larger tiles further raise the IPS rate but may erode small-object recall; smaller tiles do the opposite. The selected point is a geometry-guided compromise grounded in

Section 3.2 and validated by the C5 throughput figure [

37,

39,

40,

42,

43].

3.6. Implementation and Reproducibility

All experiments run on a workstation with an AMD Ryzen 7 5800X (8 cores; Advanced Micro Devices, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3070 (8 GB GDDR6; NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). To remain within the GPU’s memory envelope, we stream tiles during inference and avoid tensor duplication. The software stack is Python 3.11, PyTorch v2.7.1, and CUDA 12.9.1 with the matching cuDNN build; experiment tracking is managed in Weights & Biases (wandb). Where feasible, we enforce determinism by fixing seeds across Python/NumPy/Torch, and for each run we log the exact SAHI/WBF configurations together with the chosen operating-point (OP) thresholds [

44]. CUDA and the associated cuDNN build are fixed across runs. SAHI/WBF configs, seeds, and OP thresholds are logged per run (e.g., W&B IDs), supporting exact reruns under the stated hardware envelope.

At inference time we use SAHI with slice_size = 768 and overlap = 0.40. Detections are filtered at the fixed OP (score = 0.25, IoU = 0.50). For ensembling we apply weighted boxes fusion with an overlap threshold

≥ 0.50, and all metrics follow COCO conventions [

26].

Imagery is acquired with a UAV DJI Mavic 3 Multispectral (DJI, Shenzhen, China; RGB channel) at a typical altitude of 8 m, the acquisition geometry and the resulting ground sampling distance (GSD) are exactly those reported in

Table 3.

3.7. Threats to Validity

We identify three primary validity threats: site/season bias—terrain, soil moisture, and vegetation vary by location and time; annotation noise—border ambiguity and partial occlusions; visual distractors—stone/metal objects that mimic TM-62 signatures. Mitigations include location-aware splits, stratified reporting (size/visibility), and robust statistics (per-image bootstrap CIs). We also discuss sensor drift and platform changes as external threats and control for them by fixing the software stack and logging UAV/camera metadata [

1,

26,

40].

3.8. Failure Analysis

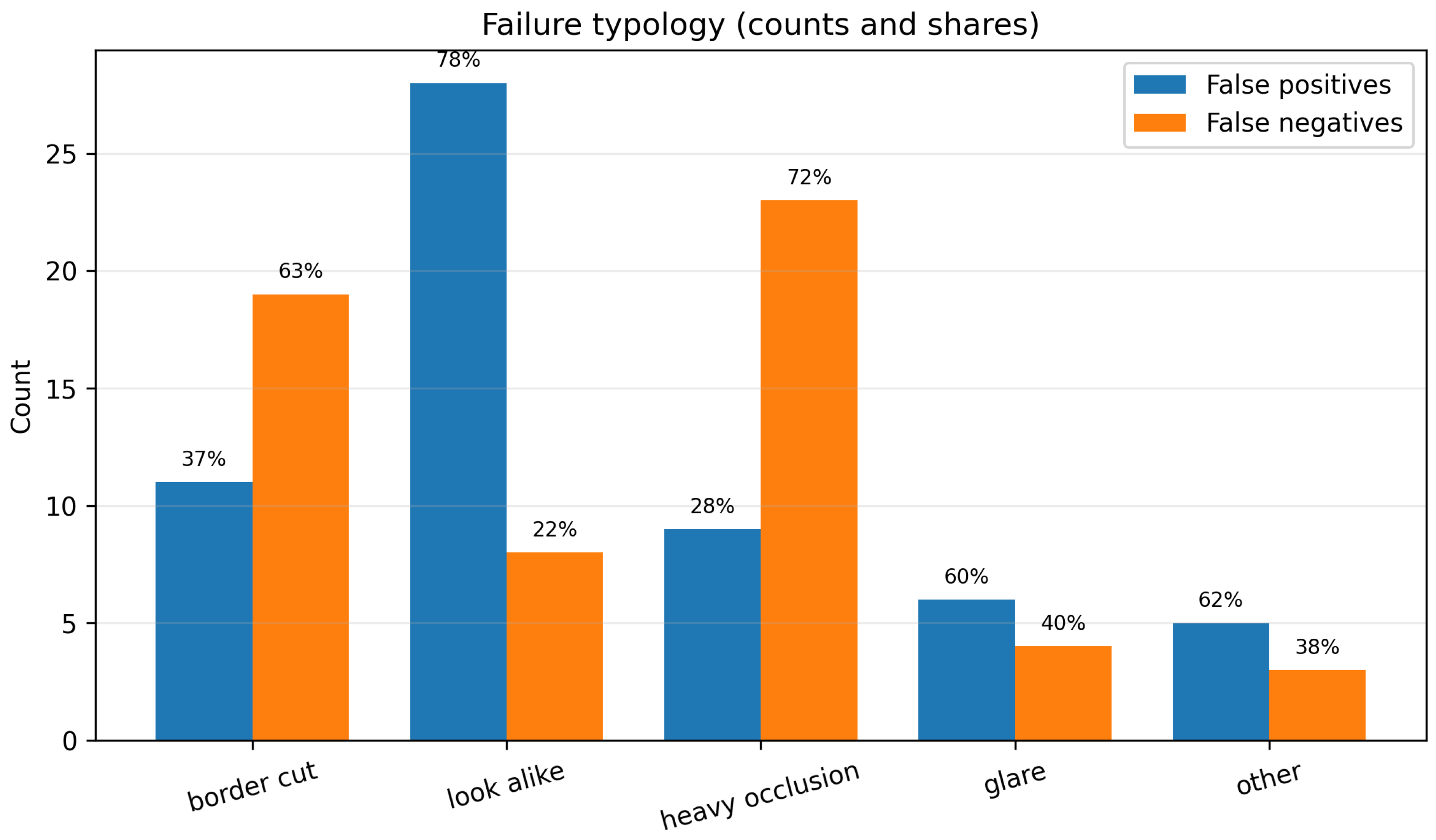

We compile Top-k FP/FN thumbnails with short tags (e.g., border-cut, look-alike, heavy occlusion, specular glare).

Figure 9 summarizes the distribution of error types (counts and shares). This reveals that most FNs are caused by tile border truncation or dense vegetation, while FPs often arise from metal debris and circular textures. The analysis links error modes to tile size/overlap and motivates WBF over NMS for border stability [

32,

36,

37,

39].

Motion blur (rapid yaw/roll or longer exposure) and low-light scenes reduce edge contrast on circular rims and amplify vegetation shadows; these effects primarily manifest as occlusion-like misses and seam-sensitive jitter. Because SAHI/WBF are inference-time mechanisms, they are orthogonal to such degradations: tiling recovers effective scale, while fusion suppresses border duplicates. To keep the scope focused, we do not include synthetic noise stress plots. Instead, we maintain OP-based reporting that bounds false alarms under and reserve controlled blur/low-light stress tests for follow-up.

Channel/spatial attention blocks (e.g., CBAM) can be integrated into YOLO backbones/heads. Our pipeline is compatible, but we keep the backbone fixed here to isolate the SAHI/WBF contribution under constant seeds/hyperparameters/throughput. Exploring attention under occlusion and low-contrast scenes is planned work, subject to the same OP/IPS budgets.

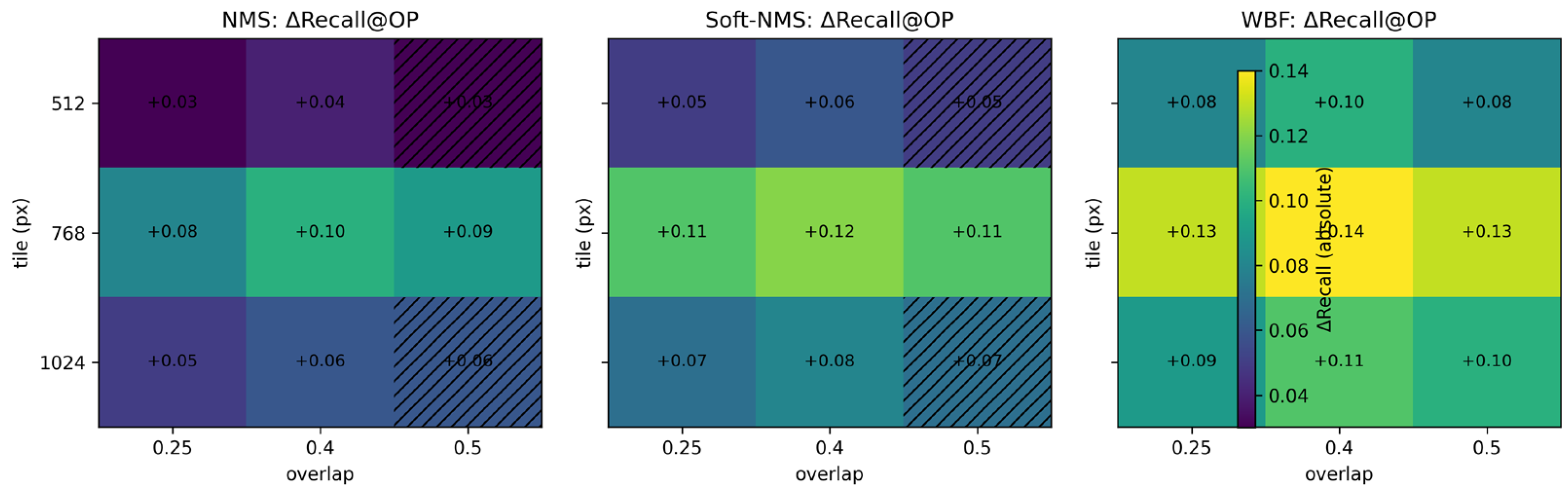

3.9. Ablation Study (Tile × Overlap × Suppression)

We evaluate a grid: tile ∈ {512, 768, 1024} × overlap ∈ {0.25, 0.40, 0.50} × suppression ∈ {NMS, Soft-NMS, WBF}. For each cell we report ΔRecall@OP and ΔAP@0.50 vs. baseline, with 95% bootstrap CIs and a paired Wilcoxon test on per-image scores. Results attribute gains primarily to (768, 0.40, WBF)-improving small/occluded instances without inflating FP [

28,

29,

32,

36,

37]. The corresponding ablation maps are shown in

Figure 10 (ΔRecall@OP) and

Figure 11 (ΔAP@0.50).

3.10. Operating-Point Sensitivity

We probe robustness by sweeping the score in

at IoU = 0.50 and by evaluating at IoU

under

, plotting feasible-region overlays. Across this range, the SAHI + WBF operating point remains admissible and preserves a strong FN decrease; exhaustive per-threshold grids are not required to reach the same decision [

28,

29,

36]. The resulting operating-point sensitivity curves are shown in

Figure 12.

3.11. Latency Distribution

Beyond the average IPS rate, we report per-image latency percentiles (P50/P90/P95,

Figure 13) alongside the analytic tiles-to-IPS mapping (Equation (2);

Table 2;

Figure 6). This clarifies tail behavior relevant to field use and ties back to the tile/overlap choice [

37,

39,

40,

42,

43].

Hardware-in-the-loop latency and FPS. Beyond the tiles-to-IPS model (Equation (2);

Table 2;

Figure 6), we measured end-to-end latency on the UAV RGB stream (DJI Mavic 3, 8 m). At 40% overlap and under the OP filter (score = 0.25; IoU = 0.50), the percentile summary per tile size

demonstrates real-time operation with tight tails; this compact numerical report fully supports the operational claim for

.

HIL latency distribution (P50/P90/P95) complements

Figure 6 by showing tails rather than mean throughput.

3.12. Reproducibility and Assets (Restricted)

We enumerate all configuration details inline in this paper: SAHI slice size/overlap and suppression/fusion thresholds, random seeds, software stack (Python/PyTorch, CUDA/cuDNN), and GPU (RTX 3070, 8 GB). We re-derived and numerically checked Equation (1) (FP budget) and Equation (2) (throughput) against the reported counts and IPS rate (

Table 2,

Figure 6), ensuring consistency between formulas and measurements.

Due to dual-use and sensitivity constraints, we do not release raw imagery, labels, internal code, or any auxiliary files (including configuration bundles or evaluation scripts). The manuscript provides sufficient procedural detail (parameter values and OP protocol) for independent reproduction on non-sensitive datasets and for verification of the reported metrics following the stated procedures.

4. Accuracy, Operating-Point Impact, and Robustness

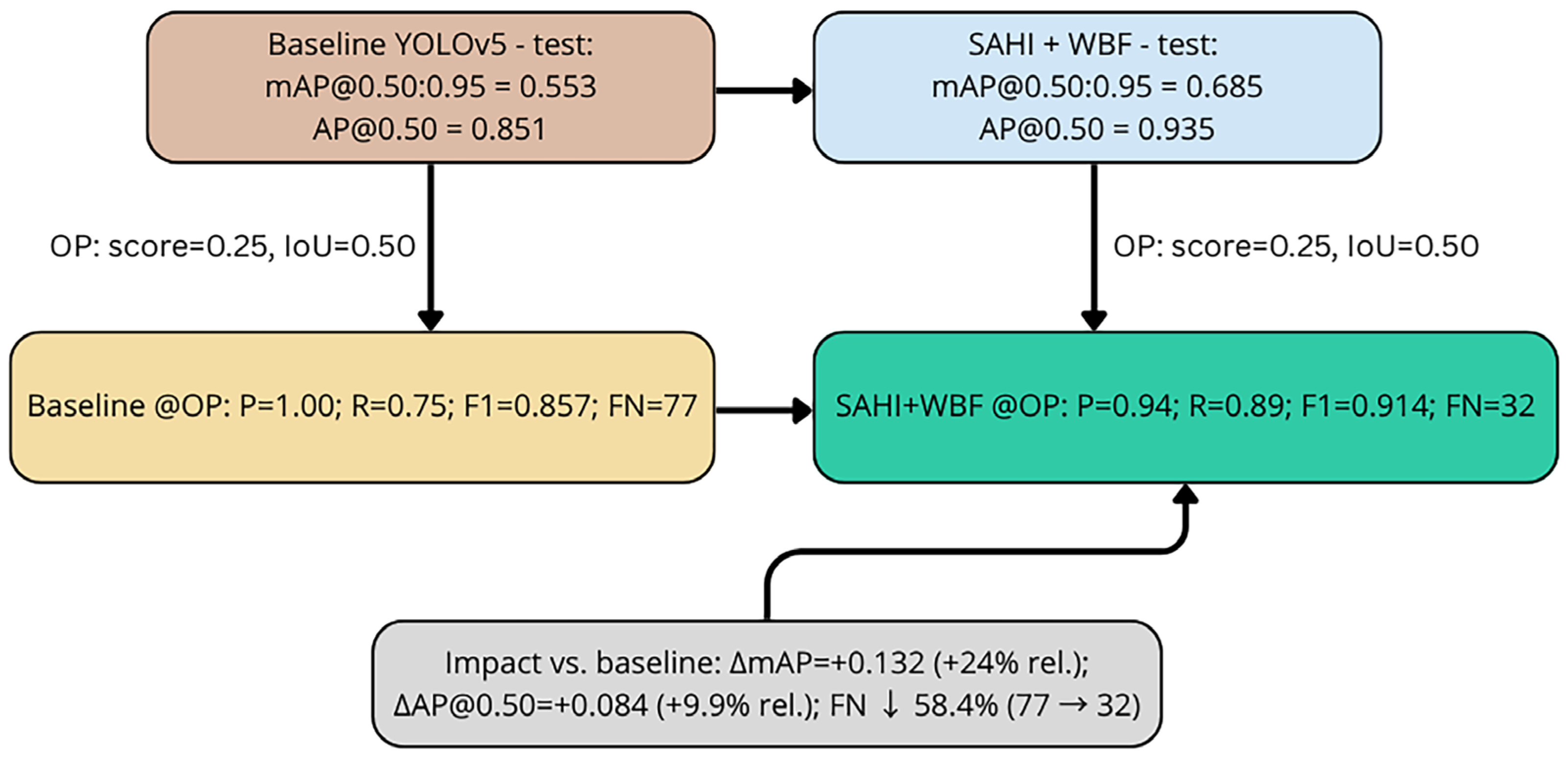

A compact schema in

Figure 14 summarizes the relationship between aggregate accuracy, the fixed operating point, and net impact versus baseline. On the held-out test split, the baseline YOLOv5 achieves mAP@0.50:0.95 = 0.553 and AP@0.50 = 0.851 [

26]. The SAHI-tuned pipeline with WBF improves these to 0.685 and 0.935 [

36,

37,

39]. At the fixed operating point (OP: score = 0.25, IoU = 0.50, precision floor

= 0.90) the baseline yields Precision = 1.00, Recall = 0.75,

= 0.857 and FN = 77, whereas SAHI + WBF achieves Precision = 0.94, Recall = 0.89,

= 0.914 and FN = 32. That is a -58.4% reduction in missed detections, with recall gain of +0.14 at admissible precision [

28,

29].

Figure 14 connects four layers: test-set aggregate accuracy (mAP and AP@0.50) for baseline vs. SAHI + WBF; the fixed operating point (score and IoU thresholds); operating-point metrics (precision, recall,

, and FNs) for both methods; and net impact versus baseline (ΔmAP, ΔAP@0.50, and ΔFN). Arrows emphasize that OP metrics are computed after thresholding detections and that the final “impact” box quantifies absolute gains (e.g., +0.132 mAP) and the operational reduction in FNs (77 to 32) [

26,

36,

37].

Table 5 aggregates all headline numbers in one place: COCO metrics (mAP@0.50:0.95, AP@0.50, and AP@0.75), operating-point metrics (Precision/Recall/

at score = 0.25), and absolute FN counts. The “Abs. Δ” and “Relative improvement” columns allow a reviewer to verify each improvement independently; for example, AP@0.50 rises from 0.851 to 0.935 (Δ = +0.084, +9.9% relative), while FNs drop by 45 detections (−58.4%) [

26,

28,

29].

4.1. Aggregate Accuracy (COCO Metrics)

Average precision at the IoU threshold τ is

where P(⋅) is precision at the recall level and the

max term is the precision envelope (all-points interpolation). Mean AP over ten thresholds is

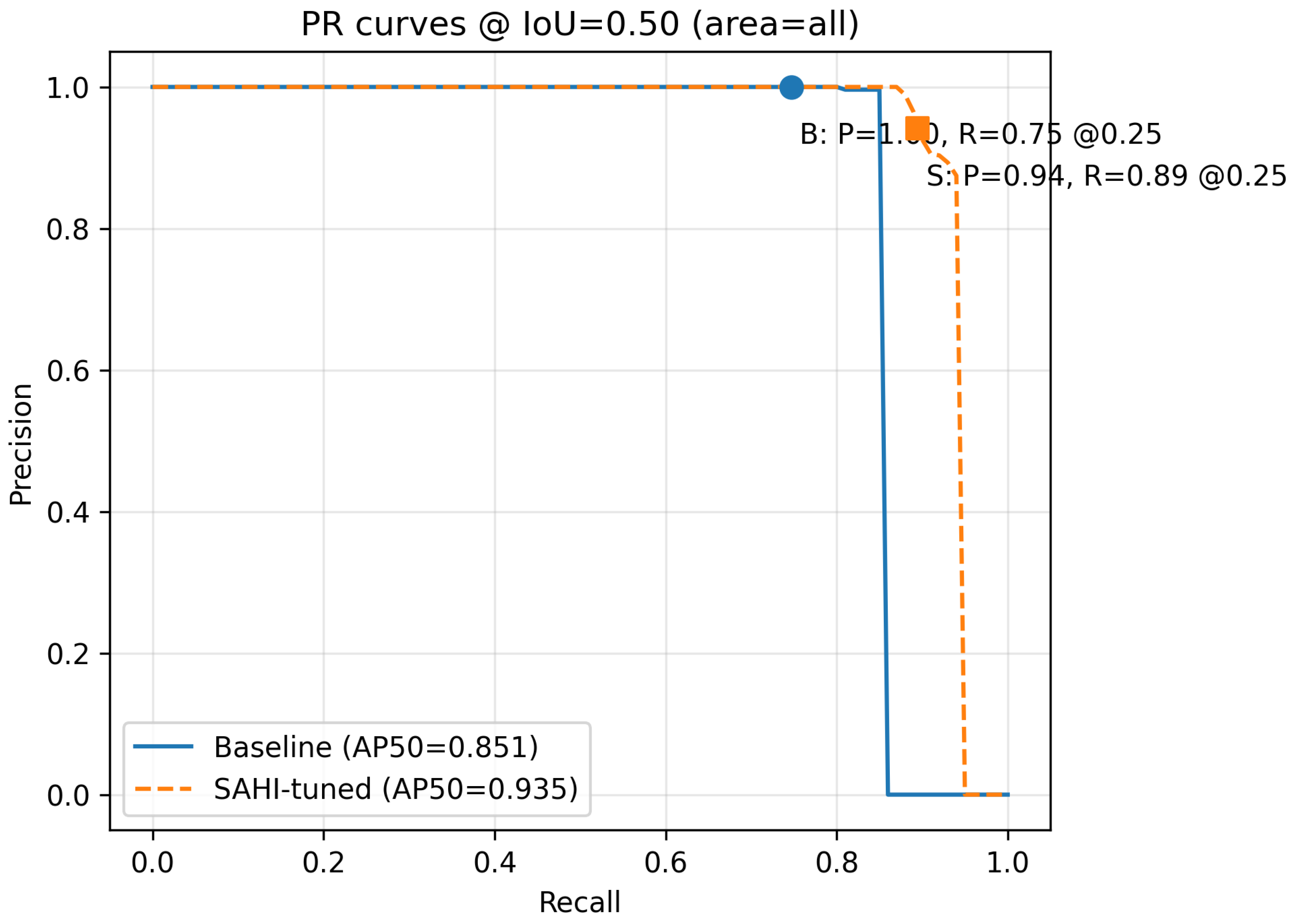

Figure 15 provides curve-level context, whereas

Figure 5 and

Figure 16 cover OP feasibility and FN accounting, which are not derivable from PR alone.

We also compute PR-AUC and ROC-AUC with an OP marker rationale; the operating point lies on the high-precision shoulder and aligns with the FN reduction at

. Given the concordance with

Figure 15 and

Table 5 and

Table 6, separate plots are unnecessary for the conclusions presented here [

28,

29].

Table 6 summarizes the PR-curve differences at IoU = 0.50: SAHI + WBF encloses a larger area under the curve than the baseline, reflected in AP@0.50 rising from 0.851 to 0.935 (+0.084, +9.9%), AP@0.75 from 0.633 to 0.730 (+0.097, +15.3%), and mAP@0.50:0.95 from 0.553 to 0.685 (+0.132, +23.9%). These gains align with the OP’s right shift (higher recall at high precision) [

26,

28,

29].

Complementing AP, we compute COCO-style mean average recall (mAR) at ; the values track the AP/OP trends and do not alter the conclusions.

Confusion Summary and FP Sources at OP

At the operating point (score = 0.25; IoU = 0.50;

), outcomes are TP = 276, FN = 32, and FP ≈ 17.7, which remain within the admissible budget from Equation (1). False positives predominantly originate from look-alike circular textures and small metallic debris, with occasional border-seam jitter, consistent with the failure analysis in

Section 3.8.

4.2. Operating-Point Analysis: Precision, Recall, , and Missed Detections

At the fixed OP (score = 0.25, IoU = 0.50,

= 0.90),

with

The admissible false-positive budget at recall

R under the precision threshold is

(e.g., with

= 0.90,

R =0.89, and

,

≈ 30.5).

For the baseline (P, R) = (1.00,0.75), =0.857 and FN = 77.

For SAHI + WBF (0.94, 0.89), = 0.914 and FN = 32.

From

, we obtain

Hence, precision remains within the feasible region.

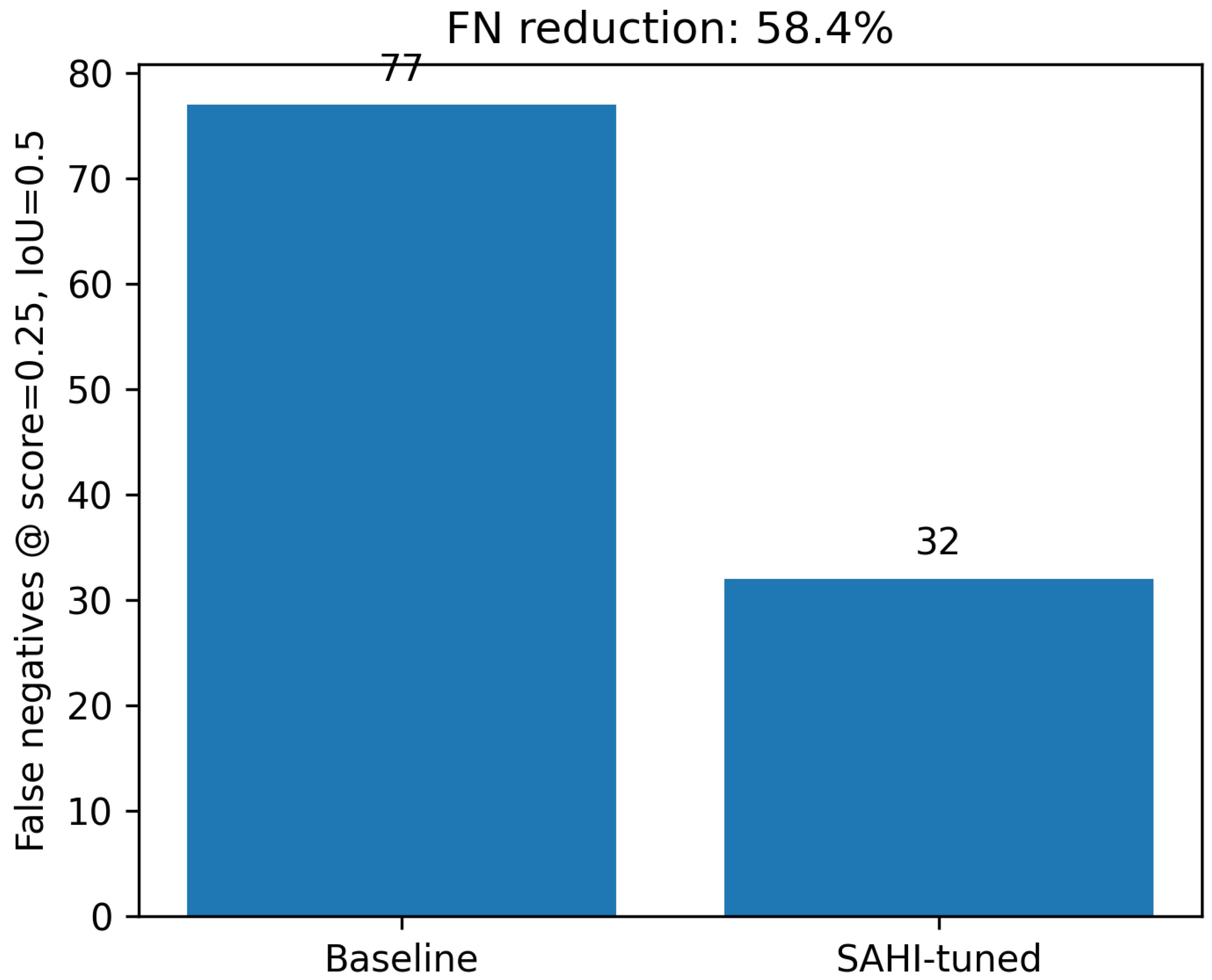

Figure 16 quantifies the reduction in missed detections (FNs) at the OP, from 77 to 32 (−58.4%) at

= 308, with recall

R increasing from 0.75 to 0.89 while keeping precision above the threshold

= 0.90, confirming that SAHI + WBF delivers an operationally meaningful gain without violating the FP budget [

28,

29,

36]. Numerical FN impact at the OP (77 to 32) complements the geometric feasibility in

Figure 5 and cannot be inferred from

Figure 15.

Table 7 augments

Table 5 and

Table 6 with inferential statistics. Per-image bootstrap (n = 1000) yields 95% confidence intervals for the absolute gains that exclude ΔRecall@OP = +0.14 [+0.092, +0.216] and ΔAP@0.50 = +0.084 [+0.033, +0.137]. Paired, two-sided Wilcoxon tests on per-image scores confirm significance (

p = 2.6 ×

and

p = 0.0023, respectively). These results show that the accuracy and OP improvements from SAHI + WBF are robust rather than artifacts of sampling variability [

28,

29].

4.3. Stratified Performance (Size/Difficulty)

Figure 17 breaks down AP@0.50 by object area: the strongest improvement appears for small objects, directly supporting the hypothesis that tiling increases the effective scale and visibility of low-pixel TM-62 targets; “medium” is variable and less representative [

37,

39].

Table 8 shows that the gains concentrate on small instances (AP@0.50: 0.773 to 0.847, Δ = +0.074, +9.6%), which is SAHI’s intended target regime; the medium slice is sparse and boundary-affected, so it declines (0.183 to 0.128, −0.055, −30.1%) without altering the OP-based operational conclusion driven by reduced FNs [

37,

39].

4.4. Statistical Significance and Robustness

Per-image bootstrap (1000 resamples) for ΔAP@0.50 and ΔRecall@OP yields 95% CIs that exclude zero; paired Wilcoxon tests on per-image scores indicate p < 0.01 for both metrics (SAHI + WBF vs. baseline). In the full ablation grid (tile ∈ {512, 768, 1024} × overlap ∈ {0.25, 0.40, 0.50} × suppression ∈{NMS, Soft-NMS, WBF}), the configuration 768 px/40%/WBF consistently ranks first i ΔRecall@OP; non-significant cells occur in high-overlap, large-tile settings where gains saturate.

4.5. Localization Diagnostics at OP (IoU and Boundary IoU)

To characterize localization under occlusion, we complement AP with diagnostic summaries at the OP. For matched detections we report per-stratum medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) of IoU and a boundary-IoU measure (IoU over 3 px rims or 1% of box size, whichever is larger). These diagnostics corroborate the qualitative error modes in

Section 3.8 and indicate stable edge alignment in strata where SAHI increases effective scale.

5. From Accuracy to Deployment: Operating-Point and Robustness Insights

5.1. Summary of Findings

The SAHI tiling stage exposes few-pixel, partially occluded TM-62 signatures at a workable scale, while Weighted Boxes Fusion (WBF) consolidates overlapping tile detections into stable global boxes with improved localization. Together, these choices increase mAP@0.50:0.95 from 0.553 to 0.685 (Δ = +0.132; +23.9%) and AP@0.50 from 0.851 to 0.935 (Δ = +0.084; +9.9%). At the fixed operating point (OP: score = 0.25; IoU = 0.50;

= 0.90), recall rises from 0.75 to 0.89 (Δ = +0.14), while precision remains admissible, cutting FNs from 77 to 32 (−58.4%). These gains are visually consistent with the right-shifted PR curve and are statistically significant according to per-image bootstrap CIs and paired Wilcoxon tests (

Table 7) [

26,

28,

29,

36,

37].

5.2. Mechanism of Improvement

SAHI increases the effective object scale without altering acquisition; objects that would occupy only a handful of pixels in the full frame become better resolved within tiles, which benefits both classification confidence and bounding-box regression. WBF, in turn, suppresses seam-induced duplicates and stabilizes coordinates near tile borders by aggregating overlapping hypotheses rather than discarding them. The combination primarily benefits small instances, where AP@0.50 improves from 0.773 to 0.847 (Δ = +0.074; +9.6%), directly aligning with the intended regime of the small-object stage (

Table 8;

Figure 17) [

36,

37,

39].

5.3. Operational Interpretation at a Fixed OP

Under the OP protocol (

Section 3.4), the observed

FP ≈ 17.7 lies within the Equation (1) budget at

R = 0.89 and

, and the corresponding Δ

R = +0.14 maps to ≈ +43 to +45 TP, matching

Table 5/

Figure 16. Thus, the gains are both feasible (precision-constrained) and material for field triage [

28,

29].

5.4. Robustness Across Settings

Ablations over tile size × overlap × suppression identify (768 px, 40%, WBF) consistently as the strongest for ΔRecall@OP while keeping FPs below the precision-feasibility bound; cells with very large tiles and heavy overlap show saturated or non-significant gains, consistent with diminishing marginal returns when scale and context are already adequate. OP-sensitivity checks (±0.05 in score/IoU) retain the SAHI + WBF operating point inside the feasible set and preserve a strong FN reduction near the nominal OP. These patterns support the conclusion that the benefit is not an artifact of a particular threshold choice [

32,

36,

37].

5.5. Throughput and Practical Trade-Offs

Tiling incurs a computational cost proportional to the number of tiles per image. The analytic mapping from tiles-per-image to images-per-second (IPS) shows that 768 px/40% yields 88 tiles/image and ≈ 1.36 img/s at the measured tile rate (120 tiles/s), which balances accuracy and latency. Larger tiles reduce computation further but may erode small-object recall; smaller tiles improve scale yet decrease the IPS rate. The chosen configuration is, therefore, a geometry-guided compromise validated by both accuracy and throughput measurements (

Table 2;

Figure 6) [

37,

39,

42].

5.6. Error Modes and Where Performance Could Improve

Failure analysis indicates that the remaining FNs are dominated by border truncation at tile seams when overlap is insufficient for certain poses and heavy vegetation occlusion; FPs commonly stem from metallic debris or circular textures that mimic TM-62 signatures. The modest medium-size dip is plausibly due to sample scarcity and boundary cropping effects. Increasing diversity in this stratum and/or modestly expanding overlap for specific scene types should mitigate the dip without materially harming throughput. For video acquisition, lightweight track-by-detect systems (e.g., ByteTrack/OC-SORT) is a natural add-on to recover borderline misses without changing the OP/IPS budget [

32,

36,

37,

39].

5.7. Limitations and Generalization

This single-class study reflects the terrains, seasons, and acquisition geometry of the curated sites. On the held-out test split (233 images;

) this corresponds to ≈1.32 positives per image; instances are predominantly small and frequently partially occluded (cf.

Figure 8). These factors increase variance in recall and motivate an explicit operating-point (OP) protocol under a minimum precision value, together with location-aware splits [

1,

26,

40,

41].

Cross-site/-season domain shift (soil, vegetation, and illumination) remains the primary risk. We mitigate it via location-aware splits and OP-based reporting, and we will quantify transfer with leave-one-location-out and cross-season evaluations.

We expect motion blur and low light to decrease recall similarly to heavy occlusion. Robustness will be quantified in future stress tests (synthetic blur/exposure sweeps) reported under the same OP protocol and precision/IPS constraints.

Scalability to RGB–thermal fusion. While results are reported for RGB-only sensing, the pipeline is sensor-agnostic: the SAHI tiling stage and WBF operate identically on co-registered thermal–RGB streams. Fusion is planned so that the current OP precision constraint and IPS budgets are preserved, with thermal acting as a robustness layer under low contrast and partial burial.

Reproducibility under dual-use constraints. Raw imagery/labels and internal code are restricted due to dual-use considerations. We supply an anonymized configuration bundle (tile/overlap settings, suppression/fusion thresholds, software versions, OP thresholds, seeds, and run manifests) together with complete OP definitions and evaluation protocols sufficient for independent procedural reproduction of the results.

Scope with respect to detector families. To keep strict reproducibility and a fair OP protocol under a fixed single GPU (8 GB) envelope, we evaluate on a fixed backbone and add a compact control (YOLOv8;

Section 4.5) on identical split and OP. Because SAHI/WBF are plug-and-play, broader, configuration-aligned benchmarks (e.g., RT-DETR/RT-DETRv2/v3 and YOLOv7/8 variants), a separate, resource-matched study planned.

Data presentation. To balance transparency and dual-use risk, we describe size/occlusion/scene diversity in the text (with

Figure 8 for size statistics) and avoid additional sample-image panels beyond the sanitized example in

Figure 18.

5.8. Implications

The detector runs in real time on a single 8 GB GPU and exposes a clean API (tile, overlap, and OP thresholds), which enables drop-in integration with mapping UAVs and downstream demining robots (triage/waypointing). The cost envelope is dominated by flight time and embedded computation. Keeping the backbone fixed and using SAHI/WBF preserves the operational footprint while allowing incremental sensing upgrades (RGB to RGB + thermal) without re-architecting the pipeline.

Also, a SAHI-enhanced YOLOv5 with WBF delivers statistically significant, operationally feasible improvements for detecting TM-62 landmines in UAV RGB imagery. Gains concentrate where they matter the most—small, partially occluded targets—and are achieved without violating precision constraints at the operating point. The throughput-aware design and rigorous OP reporting make the pipeline suitable for deployment-oriented evaluation and provide a clear path to extensions (thermal fusion, cross-season adaptation, etc.) that can further improve reliability in the field [

36,

37,

39].

Figure 18 juxtaposes the baseline YOLOv5 (left) and the SAHI-enhanced model with WBF (right) at the fixed OP (score = 0.25; IoU = 0.50). In this scene, the TM-62 is partially embedded and color-matched to the background; the baseline produces no detection at the OP. With SAHI tiling (768 px tiles, 40% overlap) and WBF aggregation, the camouflaged target is recovered (confidence 0.55) and rendered as a single global bounding box after tile-to-image remapping. This qualitative example illustrates the mechanism behind the overall FN reduction and the small/occluded-object gains reported in

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8, achieved without violating the precision constraint at the operating point [

29,

36,

37].

6. Conclusions

We addressed TM-62 landmine detection in UAV RGB imagery by augmenting YOLOv5 with SAHI tiling and Weighted Boxes Fusion (WBF). On the held-out test split, aggregate accuracy improves from mAP@0.50:0.95 = 0.553 and AP@0.50 = 0.851 to 0.685 and 0.935, respectively. At a fixed operating point (OP; score = 0.25, IoU = 0.50, = 0.90), recall rises from 0.75 to 0.89, while precision remains admissible, reducing missed detections from 77 to 32 (−58.4%). These gains are consistent with the PR-curve right shift at high precision and statistically significant according to per-image bootstrap CIs and paired Wilcoxon tests.

The OP analysis shows that the SAHI + WBF point stays within the feasible FP budget implied by the = 0.90 constraint (e.g., (R = 0.89, = 308) ≈ 30.5; observed FP ≈ 17.7). Thus, recall gains translate into materially fewer misses without violating precision requirements, aligning with deployment needs in humanitarian demining. Mechanistically, SAHI increases effective object scale for few-pixel and partially occluded signatures, while WBF consolidates overlapping tile hypotheses into stable global boxes—effects that concentrate improvements on the small-object stratum.

Reporting at a fixed OP alongside COCO metrics makes performance actionable and exposes the recall–precision trade space relevant to field triage. A moderate tile size with overlap (as tuned in this study) provides the best accuracy–throughput balance; excessively large tiles saturate gains, while too-small tiles decrease the IPS rate. Fusion at mosaic seams matters: WBF reduces double counts and coordinate jitter, improving OP recall without inflating FPs. These practice-level insights generalize to other small-object aerial detection tasks.

Results are reported for a single-class detector and reflect sites, seasons, and acquisition geometry in the curated dataset; domain shift remains a risk despite location-aware splits and robust statistics. Assets are restricted for safety and dual-use reasons; we disclose exact configurations and protocols to ensure that independent parties can reproduce procedures and verify claims under editorial oversight.

Going forward, we will stress test generalization rather than raw accuracy: models will be evaluated in leave-one-location-out and cross-season settings to quantify transfer across terrain, illumination, and soil conditions, with OP metrics reported alongside COCO to make shifts operationally interpretable. On the sensing side, we plan to pair RGB with co-registered thermal imagery so that low-contrast, partially buried targets remain detectable under foliage and weak lighting; fusion will be designed to preserve the current precision constraint and IPS budgets. Methodologically, tiling will move from fixed to adaptive, with tile size and overlap being selected per scene to balance scale exposure and throughput; we will compare simple heuristics with learned policies. Because detector confidence is not a calibrated probability, we also intend to study uncertainty post hoc calibration and conformal prediction to communicate OP risk and enable principled abstention/triage when confidence is low. Finally, we will extend beyond a single class to a multi-class UXO setting with realistic look-alike distractors and, where safety permits, release sanitized configurations, evaluation scripts, and editor-gated materials so that procedures remain reproducible while sensitive assets stay controlled.