Abstract

We present a new word embedding technique in a (non-linear) metric space based on the shared membership of terms in a corpus of textual documents, where the metric is naturally defined by the Boolean algebra of all subsets of the corpus and a measure defined on it. Once the metric space is constructed, a new term (a noun, an adjective, a classification term) can be introduced into the model and analyzed by means of semantic projections, which in turn are defined as indexes using the measure and the word embedding tools. We formally define all necessary elements and prove the main results about the model, including a compatibility theorem for estimating the representability of semantically meaningful external terms in the model (which are written as real Lipschitz functions in the metric space), proving the relation between the semantic index and the metric of the space (Theorem 1). Our main result proves the universality of our word-set embedding, proving mathematically that every word embedding based on linear space can be written as a word-set embedding (Theorem 2). Since we adopt an empirical point of view for the semantic issues, we also provide the keys for the interpretation of the results using probabilistic arguments (to facilitate the subsequent integration of the model into Bayesian frameworks for the construction of inductive tools), as well as in fuzzy set-theoretic terms. We also show some illustrative examples, including a complete computational case using big-data-based computations. Thus, the main advantages of the proposed model are that the results on distances between terms are interpretable in semantic terms once the semantic index used is fixed and, although the calculations could be costly, it is possible to calculate the value of the distance between two terms without the need to calculate the whole distance matrix. “Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen”. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. L. Wittgenstein.

MSC:

68T35; 46B85; 28C15

1. Introduction

Nowadays, the fast improvement of natural language processing (NLP) can be seen in how all the applications of this discipline have reached impressive heights in the handling of natural language in many applied fields, ranging from the translation from one language to another, to the generalization of the use of generative artificial intelligence [1,2,3,4]. A fundamental tool for these applications is the so-called word embeddings. Broadly speaking, word embeddings allow representations of semantic structures as subsets of linear spaces endowed with norms. The distance provided by such a norm has the meaning of measuring the relations among terms in such a way that two items being close means that they are close with respect to their meaning. The main criticism of this technique when it was first introduced is that, once a word embedding is created, its representation remains static and cannot be adapted to different contexts [1,3]. This is a problem for applications, as there are words whose meaning clearly depends on the context: take the word “right”, for example. However, since the late 2010s, these models have evolved towards more flexible architectures, incorporating structural elements and methods that allow the integration of contextual information [5,6,7].

On the other hand, let us recall that the technical tools for natural language processing have their roots in some broad ideas about the semantic relationships between meaningful terms, but they are essentially computed from “experimental data”, that is, searching information in concrete semantic contexts provided by different languages. Thus, one of the basic ideas underlying language analysis methods could be called the “empirical approach”, which states that the meaning of a term is reflected in the words that appear in its contextual environment. An automatic way of applying this principle and transforming it into a mathematical rule is to somehow measure which sets of semantically non-trivial documents in a given corpus share two given terms. This is the essence of the method based on the so-called semantic projections used in this paper [8,9].

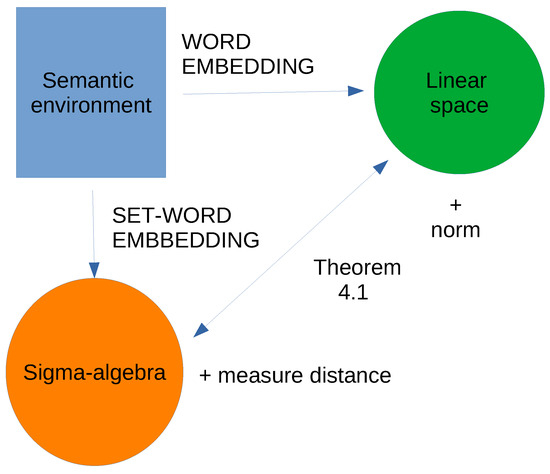

The aim of this article is to present a new mathematical formalism to support all NLP methods based on the general idea of contextual semantics. Thus, we propose an alternative to the standard word embeddings, which is based on a different mathematical structure (instead of normed spaces) developed using algebras of subsets endowed with the usual set-theoretic operations (Figure 1). In a given environment and for a given specific analytical purpose, the meaning of a term may be given by the extent to which it shares semantic context with other terms, and this can be measured by means of the relations among the sets representing all the semantic elements involved [10,11]. The value of the expression “the term v shares the semantic environment with the term w” can be measured by a real number in the interval given by a direct calculation, which is called the semantic projection of v onto This representation by an index belonging to is also practical when we think about the interpretation of what a semantic projection is, since it can be understood as a probability—thus facilitating the use of Bayesian tools for further uses of the models—as well as a fuzzy measure of how a given term belongs to the meaning of another term—thus facilitating the use of arguments related to fuzzy metrics.

Figure 1.

Word embedding versus set-word embedding.

Thus, we present here a mathematical paper, in which we define our main concepts and obtain the main results on the formal structure that supports empirical approaches to NLP based on the analysis of a corpus of semantically non-trivial texts, and how meaningful terms share their membership in these texts. The main outcome of the paper is a theoretical result (Theorem 2) which aims to demonstrate that our proposed method is universal, in the sense that any semantic structure which is representable through conventional word embeddings can also be represented as a set-word embedding, and vice versa. However, our approach to constructing representations of semantic concepts, while limited to the idea that semantic relationships are expressed through distances, is much more intuitive. This is because it is grounded in the collection of semantic data associated with a specific context. Thus, the key advantage of our model lies in its adaptability to contextual information, allowing it to be applied across various semantic environments.

This paper is structured as follows. In the subsequent subsections of this Introduction, we outline the specific context of our research, covering standard word embeddings, families of subsets in classical NLP models, and relevant mathematical tools. We will also give an overview of the word embedding methods that have appeared recently and are closely related to the purpose we bring here. After the introductory Section 1 and Section 2, Section 3 introduces the fundamental mathematical components of our semantic representations, demonstrating key structural results and illustrating how these formal concepts relate to concrete semantic environments. To ensure a comprehensive understanding of our modeling tools, Section 4 presents three particular examples and applications. Following this motivational overview, Section 5 details the main result of the paper (Theorem 2), explaining its significance and providing further examples. Section 6 is devoted to the discussion of the result, built around a concrete example that allows the comparison of our tool with, firstly, the Word2Vec word embedding, and in a second part, with a more recent selection of word embeddings that we have considered suitable for their relation to our ideas. Finally, Section 7 offers our conclusions.

2. Related Work

In this section, we provide an overview of the relevant background literature and introduce the key concepts that will be utilized throughout the remainder of the paper.

2.1. Word Embeddings and Linear Spaces

Let us start this part of basic concepts by explaining what a word embedding is and showing in broad strokes the “state of the art” regarding this important NLP tool. Word embeddings have revolutionized natural language processing (NLP) by representing sets of words (in general, semantic items) as dense subsets of vectors in a high-dimensional linear space, capturing semantic and syntactic relationships. These representations operate on the principle that words appearing in similar contexts tend to have similar meanings. The learning process of word embeddings using neural networks involves initializing word vectors randomly and then training the network to predict words based on their context or vice versa. This approach has evolved significantly over time, with several key models marking important milestones. Word2Vec [4] utilized shallow neural networks with a single hidden layer, proposing two efficient architectures: Continuous Bag-of-Words (CBOW) and Skip-gram. The CBOW architecture predicts a target word given its context, using the average of the context word vectors as input to a log-linear classifier. Conversely, the Skip-gram model predicts the context words given a target word, effectively inverting the CBOW architecture. Although the algorithms become rather technical, the main idea behind these models is to obtain a linear representation of the semantic space in which distances (measured by means of norms) represent meaning similarity. Therefore, these models focused on capturing word relationships in vector space and introduced innovations such as negative sampling and hierarchical softmax for efficient training. Building upon this foundation, GloVe was developed [5], which combined global matrix factorization with local context window methods, explicitly modeling the ratio of co-occurrence probabilities. GloVe’s architecture involves a weighted least squares regression model that learns word vectors by minimizing the difference between the dot product (scalar product of the underlying Euclidean space) of word vectors and the logarithm of their co-occurrence probability.

A paradigm shift occurred with the introduction of BERT [2] and GPT [6], which moved from static word embeddings to contextual embeddings and introduced the “pretraining and fine-tuning” paradigm. BERT utilized a bidirectional transformer architecture for capturing rich contextual information. The transformer architecture, first proposed in [7], relies on self-attention mechanisms to process input sequences in parallel, allowing for more efficient training on large datasets. BERT’s pretraining involves two tasks: Masked Language Modeling (MLM), where the model predicts masked tokens in a sentence, and Next Sentence Prediction (NSP), where it predicts if two sentences are consecutive in the original text. This bidirectional approach allows BERT to capture context from both left and right of a given word. On the other hand, GPT demonstrated the power of unidirectional language modeling at scale, using only the decoder portion of the transformer architecture. GPT’s architecture processes text from left to right, predicting each token based on the previous tokens, which allows for efficient generation of coherent text.

These advancements reflect key trends in the field, including increasing model size and complexity, a shift from local to global context, evolution from static to dynamic embeddings, and a growing emphasis on unsupervised pretraining on large corpora. The progression from word-level to subword-level tokenization methods, such as WordPiece used in BERT and byte-pair encoding used in GPT, has further enhanced the capability of these models to handle diverse vocabularies and capture nuanced semantic information.

In recent times, more advanced methods have been introduced that affect the way data are treated to achieve better information processing to build word embeddings, as well as to improve and diversify applications. NLP models are a highly active research area, with significant advancements made each year. Methods such as LDA, LSA, PLSA, Bag of Words, TF-IDF, Word2Vec, GloVe, and BERT, among other natural language processing applications (see, for example, ref. [12] for an overview of these models), have become foundational in the field, despite some of them being just eight years old. These paradigms continue to evolve, and the range of applications has expanded so much that it has become increasingly difficult to track which models are leading in terms of performance. However, recent advances show a clear shift towards more contextualized and formal structures in some new techniques, with a greater focus on how information is represented and processed [13]. Despite the diversity in approach, most of these models rely on high-dimensional Euclidean spaces as their core structure. Additionally, methods for introducing complementary information into models are rapidly evolving, with novel approaches emerging for improved learning [14,15]. A comprehensive analysis of these new methodologies is beyond the scope of this paper, but understanding the direction in which these techniques are evolving is essential for our work.

But these modifications have not affected the main representational structure underlying the word embeddings, i.e., the mathematical environment chosen to establish a conceptual isomorphism between a semantic context and a formal structure: the linear normed space. As will be seen, in this paper we propose an alternative mathematical context, provided by Boolean algebras of subsets endowed with metrics specially designed for the representation of semantic structures.

2.2. Classes of Subsets as Natural Language Models

As outlined in the previous section, the methods for representing semantic relations through word embeddings fundamentally employ a linear space representation. This is achieved by mapping a set of tokens with significant semantic value into a normed space. Initially, these items are embedded as independent vectors within a high-dimensional linear space. Various procedures, such as encoder–decoder methods (see [3]), then enable the reduction of the representing space’s dimensions while also adjusting the (Euclidean) distances to reflect the semantic proximity among the terms. This approach creates a highly effective framework for applications. However, conceptually, representations based on classes of sets—capturing the notion that semantic relations among terms can be expressed as inclusions, unions, and intersections—are arguably more appealing. This perspective aligns more closely with our intuitive understanding of semantic relations.

It is worth noting that this idea is not new in the field of natural language processing. For instance, Zadeh’s original work, which laid the groundwork for fuzzy set theory, fundamentally addressed these types of mathematical structures [10]. The core premise of fuzzy set theory is that membership in a set is not merely a Boolean variable but, rather, a continuous variable. In other words, a semantic term (such as a word, token, or item) belongs to a given concept to a degree represented by an index with values ranging from 0 to 1, indicating the intensity of that relationship. For example, while “lion” belongs to the concept of “animal”, “healthy” relates to “happiness” at a certain (high) coefficient, which does not reach 1, since healthy individuals are not necessarily happy. Moreover, standard operations in vector spaces—such as addition and scalar multiplication—do not accurately reflect the properties of semantic relationships between words. While some attempts to bridge this gap have been rigorously explored in the literature (see [1,16,17]), they have yet to fully align with intuitive semantic notions.

This context presents a broader view: linear space word embeddings are highly effective operationally, yet they often lack the intuitive appeal found in using algebras of subsets as a mathematical foundation for NLP. The primary focus of this paper is to demonstrate that both representations are, in fact, equivalent. Specifically, every vector-valued word embedding can be interpreted as a set-word embedding, and vice versa. This is presented and proved in Theorem 2.

2.3. Mathematical Tools

Let us explain here some notions that will be necessary for the explanation of the ideas in this paper, that, as we said, is mainly of mathematical nature. We will use standard definitions and notations of set theory, measure theory, metric spaces, and Lipschitz functions.

Let us recall first what a algebra of subset is. Consider a set A algebra is a class of subsets of X that is closed under countable unions and complements of elements of That is, if then and belongs to too if As a consequence, finite intersections of elements also belong to the algebra.

A (countably additive real) positive measure on a algebra is a function that is countably additive when acting on countable families if pairwise disjoint sets, and allows us to define integrals of real valued measurable functions. The examples that we show in the paper are constructed using what are referred to as (strictly positive) atomic measures which means that for every set with a single point of

Let us provide now the basics on the metric spaces we use as mathematical support. Consider a set X and a positive real function If it satisfies that for every we have that (1) if and only if (2) and (3) it is said that d is a metric, and is a metric space. In this paper we will consider a special type of metric space for which the elements are subsets of a given set belonging to a algebra This will be endowed with particular metrics to become a metric space, which will be fundamental for our representation of the semantic relations.

Given a metric space with a distinguished point the Arens–Eells space (also called the free space) is defined as the vector space of all the molecules. We will define it later; let us first introduce some elementary notions. Consider another metric space . A function is called Lipschitz if there exists a constant such that

The relation between metric spaces and normed linear spaces is fundamental for this paper, so let us center the attention in which is a Banach space . The class of Lipschitz mappings from X to E that vanish at 0 is a Banach space, denoted by . The Lipschitz norm for a map is the smallest constant such that

The case in which E is the Euclidean real line , the notation , is often used. This is space is known as the Lipschitz dual of X. Let us introduce now the so-called Arens–Eells space of a metric space denoted by [18], which is a fundamental piece of the construction presented in this document. Sometimes is referred to as the free space associated with and has the main feature that it is the predual of that is,

The essential vectors of (from which the space is generated) are the so-called molecules on X. A molecule is a real-valued function m on X with finite support, satisfying . This means that all of them can be written as finite sums and differences of simple molecules that are described below. If , the molecule is given by where denotes the characteristic function of the set , that is, the functions that equals 1 at S and 0 out of The space of all the molecules is the real linear space .

A norm can be given for this space. If we consider a representation as and its norm is defined as

where infimum is computed over all possible representations of m as the one written above. The norm completion of is called the Arens–Eells space, . The function given by is an isometric embedding of X into .

3. Set-Word Embeddings: The Core

Word embeddings are understood to take values in vector spaces. However, as we explain in the Introduction, our contextual approach to automatic meaning analysis suggests that perhaps a different embedding procedure based on set algebra would better fit the idea of what a word embedding should be. Let us show how to achieve this.

We primarily consider a set of words and a algebra of subsets of another set S.

Definition 1.

A set-word embedding is a one-to-one function

In this setting, it is natural to consider the context provided by the Jaccard (or Tanimoto) index, which is a similarity measure that has applications in many areas of machine learning that is given by the expression

where A and B are finite subsets of a set It is also relevant that the complement of this index,

is a metric [19] called the Jaccard distance. The general version of this measure is the so-called Steinhaus distance, which is given by

where is a positive finite measure on a algebra , and are measurable sets ([20], S.1.5). The distance proposed in [21] is a generalization of these metrics.

Let us define a semantic index characteristic of the embedding which is based on a kind of asymmetric version of Jaccard’s index. In our context, and because of the role it plays for the purposes of this article, we call it a semantic index of one meaningful element onto another in a given context. In the rest of this section, we assume that is a finite positive measure on a set acting on a certain algebra of subsets of

Definition 2.

Let The semantic index of B on A is defined as

Therefore, once a measurable set A is fixed, the semantic index is a function

Those functions are called semantic projections in [9]. Roughly speaking, this rate provides information about which is the “proportion of the meaning” of A that is explained/shared by the meaning of But this is a mathematical definition, and the word “meaning” associated with a subset is just the evaluation of the measure on it. As usual, plays the role of measuring the size of the set A with respect to a fixed criterion.

In [9], the definition of semantic projection was made in order to represent how a given conceptual item (canonically, a noun) is represented in a given universe of concepts. With the notation of this paper, given a term A and a finite universe of words the semantic projection is defined as a vector ([9], S.3.1) in which each coordinate is given by

where B is the subset that represents the noun u of the universe in the word embedding ([9], S.3.1). These coefficients essentially represent a particular case of the same idea as the semantic index defined above, as for being the counting measure,

We call it semantic index instead of semantic projection to avoid confusion.

Let us now define the framework of non-symmetric distances for the model.

Definition 3.

Let be a algebra of subsets of a given set Let μ be a finite positive measure on We define the functions

as well as

Let us see that the so-defined expressions provide the (non-symmetric) metric functions that are needed for our construction. As in the case of the Jaccard index mentioned above, there is a fundamental relationship between and , which is given in (iii) of the following result.

Lemma 1.

Fix a σ-algebra on and let μ be a finite positive measure on the measurable sets of Then,

- (i)

- and are conjugate quasi-metrics on the set of the classes of a.e. equal subsets in

- (ii)

- is a metric on this class.

- (iii)

- For every

Proof.

Note that, for every

Consider

Clearly,

and so both expressions define conjugate functions. Then,

and the same happens for and so both and are quasi-pseudo-metrics. To see that they are quasi-metrics, we have to prove (ii), that is, that the symmetrization

is a distance (on the class of a.e. equal sets). But if we have that both

This can only happen if and so a.e. As is symmetric and satisfies the triangle inequality, we obtain (ii), and so (i).

(iii) For every

and

□

It can be seen that the metric that we have defined coincides with the so-called symmetric difference metric (the Fréchet–Nikodym–Aronszyan distance, which is given by (see [20], S.1.5). However, our understanding of relations between sets is essentially non-symmetric, since semantic relations are, in general, not symmetric: to use a classical example, in a set-based word representation, it makes sense for the word “king” to contain the word “man”, but not vice versa. It seems natural that this is reflected in the distance-related functions for comparing the two words. This is why we introduce metric notions using quasi-metrics as primary distance functions. It must be said that, in the context of the abstract theory of quasi-metrics, the distance is used instead of (see, for example, [22]). It is equivalent to and plays exactly the same role as from the theoretical point of view: we use for its computational convenience, as we will see later.

Summing up the information presented in this section, we have that the fundamental elements of a set-word embedding are the following.

- A set of terms (words, short expressions, …) on which we want to construct our contextual model for the semantic relations among them.

- A finite measure space in which the algebra of subsets have to contain the subsets representing each element of and S can be equal to W or not.

- The word embedding itself: an injective map that is well defined as a consequence of the requirement above.

- The quasi-metrics and which, together with the metric give the metric space that supports the model.

Remark 1.

In principle, it is required that μ be positive. However, this requirement is not necessary in general for the construction to make sense, and it is even mandatory to extend the definition for general (non-positive) finite measures, as will be shown in the second part of the paper. What is actually required is that the symmetric differences of the elements of the range of the set-word embedding have positive measure. We will see that this is, in fact, weaker than being a positive measure.

The next step is to introduce a systematic method for representing the features we need to use about the elements of W that would help to enrich the mathematical structure of the representations. This is achieved in the next subsection.

3.1. Features as Lipschitz Functions on Set-Word Embeddings

By now we have already introduced the basic mathematical tools to define a set-word embedding. The method we used to perform it made them derived from a standard index, which we call the semantic index of a word with respect to another word It has a central meaning in the model. We prove that it is a Lipschitz function in Theorem 1 below. In a sense, we think of it as a canonical index that shows the path to model any new features we want to introduce into the representation environment.

Our idea is also influenced by the way some authors propose to represent the “word properties” for the case of vector-valued word embeddings (we use “i” for this map to follow the standard notation for inclusion maps, but the reader should be careful because it can sometimes be confusing). Linear operations on support vector spaces are widely used for this purpose [1,8,16,23,24]. Thus, linear functions are sometimes used to define what are called semantic projections, which can be written as translations of linear functionals of the dual space of the vector space For example, to represent the feature “size” in a word embedding of animals, it is proposed in [8] to use a regression line, and this defines what they call a “semantic projection”. The same idea is used in [9]; in this case, the semantic projections are given by the coordinate functionals of the corresponding vector-valued representation.

This opens the door to our next definition. But in our case, we do not have any kind of linear structure, so we have to understand our functions as elements of the “dual” of the metric space If we take the empty set as a distinguished point 0 in this dual space is normally defined as the Banach space of real-valued Lipschitz functions that are equal to 0 at The norm is defined as if we do not assume that is 0 at and then is also a Banach space (see, e.g., [25,26] for more information on these spaces).

Definition 4.

An index representing a word-feature on the set-word embedding is a real-valued Lipschitz function In the case that there is a constant such that φ satisfies also

we will say that φ is a Katětov (or -normalized) function (index). We write for the infimum of such constants

Lipschitz functions with and satisfying the second condition for are often called Katětov functions (see, for example, ([20], S.1)). Under the term -normalized index, the second requirement in this definition is used in [27] in the context of a general index theory based on Lipschitz functions. More information on real functions satisfying both requirements above can be found in this paper.

A standard case of Katětov Lipschitz functions (called sometimes Kuratowski functions, standard indices in [27]) are the ones given by for a fixed Indeed, note that for

for every This, together with a direct computation using , show that and Indeed, note that under the assumption that S is finite, we can easily see the following:

- (1)

- For every Lipschitz function , we can find a real number a non-negative Lipschitz function and a set such that and .

- (2)

- and that is, can be translated to obtain a non-negative function obtaining the value 0 at a certain set and preserving the Lipschitz constant; also, a direct calculation, as per the one above for , shows that the product of can never be smaller than

The functions described above are a particular application of the so-called Kuratowski embedding [28], which is defined as the map given by the formula where is a metric space, is the Banach space of all bounded continuous real-valued functions on X, and is a fixed point of If we take we obtain our functions.

The above notion motivates the following definition of compatibility index. For a Lipschitz index the compatibility index given below gives a measure of how close is to the given metric in space, such that a small value (it always has to be greater than 1) indicates that there is a close correlation between the relative values of in two generic subsets A and B and the value of the distance Conceptually, a small value of represents the (desired) deep relationship between the semantic index and the metric in the space, thus functioning as a quality parameter for the model.

Definition 5.

Let be a Lipschitz Katětov positive function attaining the value 0 only at one set We call the constant given by

the compatibility index of φ with respect to the metric space We have already shown that

The importance of the compatibility index in the proposed metric model is clear: the smaller the constant , the better the index fits the metric structure. That is, whenever we use to model any semantic feature in the context of the set-word embedding we can expect the feature represented by to “follow the relational pattern between the elements of W” as closely as is small. Let us illustrate these ideas with the next simple example.

Example 1.

Two different features concerning a set of nouns (for example, two adjectives) do not necessarily behave in the same fashion. For example, take w1 = w2 = w3 = and two properties: , which represents the adjective “big”, and which represents “fierceness”. We can define the degree of each property by

and

Consider the trivial set-word embedding where for and μ is the counting measure on the algebra of subsets of Then,

Obviously, both indices are Lipschitz, and and On the other hand, both of them are Katětov functions with and

Let us compute the compatibility indices associated with both and First, note that has to be translated to attain the value let us define We have that so

and

Following the explanation we have given for we have that better fits than

Note that we cannot expect any kind of linear dependence among the representation provided by and the functions representing these properties. For example, the index that concerns the size can be given by the line while the second one, , does not satisfy any linear formula. In fact, it does not make sense to try to write it as a linear relation, as there is no linear structure on the representation by the metric space

From the conceptual point of view, this is the main difference of our purpose of set-word embedding versus the usual vector-word embedding. The union or intersection of two terms has a semantic interpretation in the model: the semantic object created by considering two terms together in the first case, and the semantic content shared by the two terms, respectively. However, the addition of two terms in their vector space representations or the multiplication of the vector representation of a given word by a scalar have dubious meanings in the models, although they are widely used [8,17,23].

Let us show now that the semantic index is a Lipschitz index, and even Lipschitz, and Katětov with for being a probability measure and The main idea underlying the following result, which is fundamental to our mathematical construction, is the existence of a deep relationship between semantic indexes and the metric defined by a given measure Essentially, this means that the model can be structured around the notion of semantic index, which has the clear role of a measure of the shared meaning between two terms, and an associated metric, which allows the comparison and measurement of distances between semantic terms.

Theorem 1.

For every the function is Lipschitz with constant That is,

Moreover, for , we also have

and then

Proof.

As taking into account that

(the same for ), we have that

The symmetric calculations give

Therefore,

For the last statement, just note that

In particular, if is a probability measure, the function above satisfies the inequalities

and so it is a Katětov function such that □

This result is fundamental to the interpretation of the model. Roughly speaking, it states that the main index on which we have relied conforms completely to the metric structure. Since is a probability measure, the semantic index for the case represents the rate (the score per one) of information contained in any information set which is measured by Thus, Theorem 1 () means that this fundamental quantity absolutely fits the space the main tool of our embedding procedure.

3.2. How to Apply a Set-Word Embedding for Semantic Analysis: An Example

To finish this section, let us sketch how the proposed model can be used for semantic analysis. We only intend to show some general ideas in this paper, and compare them with the ones that are usual tools in the context of the vector-word embeddings.

Let us focus our attention on a binary property that regards a set of words representing nouns of a certain language. Write for the metric space defined by all the subsets of with a probability measure space, and let the set-word embedding in which we base our model (note that this “” is not the usual “i” used before to denote a standard word embedding.) The set S could be, for example, a class of properties of the animals: average size, taxonomic distance, common color, eat grass or not…, and embeds every animal in the set of properties that it has. The measure quantifies the relevance in the model that each of the properties in S has.

The studied feature is described by the values 0 or so we call the Lipschitz functional with values in representing the feature a classifier. For example, in a given set of animals W, the property of having two legs is represented by and having four legs, by Let us write for the Lipschitz map representing the property “having two/four legs”. Let us consider a specific situation, and how to solve it using the proposed set-word embedding.

- Suppose that we know the value of the classifier at a subset but it is unknown out of

- The value of in can be estimated using the evaluation on some terms of the original universe and then extending using a McShane–Whitney type formula. This extension provides the equationwhich gives an estimate of the value of with values in the interval for elements that do not belong to

- Therefore, the structure of the metric space together with the explained Lipschitz regression tool provide information about the expected values of in the set Since it takes values in the interval but not necessarily in we can interpret the values provided by in probabilistic terms: it gives the probability that a given element of has two or four legs. Also, we can interpret it as the fuzzy coefficient of that element belonging to the set of four-legged animals.

4. Three Related Constructions

We show in this section three general frameworks in which the formalism explained can be used for semantic analysis. They are built from scratch, and we try to demonstrate with them how adaptable our method is by introducing set-theoretic arguments into the reasoning.

4.1. A Database of Dictionaries

We will show a specific construction for the semantic contextual analysis of a set of nouns N using a collection of dictionaries. Finding a good set of nouns for the analysis of a given semantic context would be an important preliminary work for a useful application of the abstract procedure described below. This problem is, in a sense, similar to the determination of a suitable set of words describing a given semantic environment using keywords [29]. Many techniques from natural language processing have been proposed to help in this process (Word Sense Disambiguation algorithms to obtain the best SynsetID; see [29] and the references therein). Something similar should be performed as a first step in our case. Wikipedia could be the source of information instead of our “collection of dictionaries”.

Let us describe the constructive process step by step. Consider a fixed set of nouns, N, on a certain topic (for example, for Sociology of Migration: “culture”, “acculturation”, “assimilation”, “autochthonous”, …,“process”, “change”,“system”, …).

- Consider a family of R dictionaries. Let us fix a word n in and consider the text appearing in the dictionary entry associated with Let us define the set of words appearing in each of these texts.

- Now, take the sets and define the class of subsetsThis is the basic set of elements we consider in this example. Each of them represents the set of nouns that are used, in all dictionaries, to give a definition of a given noun n, including the noun itself.

- Following our construction, take the algebra generated by the subsets of N, and note that Define the word embeddingThus, each noun is represented in the set-word embedding as the set of nouns appearing in all the entries of this word in the dictionaries of

If the counting measure is used as underlying measure for the algebra of all subsets of the quasi-distance between two nouns is given by

that is, the number of all nouns appearing in the descriptions of in all the dictionaries of that are not in the descriptions of Using also the dual definition of we obtain the metric which is their max-symmetrization.

The semantic index gives the rate of words in the definition of that are shared by Note that the lack of symmetry in the definition of this index (and also in and ) is a natural feature. For example, one can expect that

or at least that there is one more element in the counting of the left-hand side, since the word “culture” appears in all the definitions of “acculturation”, but the reverse relation could not happen.

A different measure can be used if we want the nouns of N to have different relevance in the model. For example, we can have nouns associated with the central meaning of the set N, and common nouns that are often used in similar contexts and serve to describe the main words. If we come back to the example of the Sociology of Migration, words such as “culture”, “acculturation”, and “assimilation” are central, and we assign them a weight equal to and words such as “process” or “change”, that are used to describe the others, can be weighted by That is, the fact that the word “culture” appears in the definition of “acculturation” is central for the coding of its meaning, while the occurrence of the word “process” just denotes that it is an action. If we divide the words of N in two sets, “Central” and “Complementary”, the following measure can be considered instead of the counting measure,

Although the choice of certain words is arbitrary if we consider them as signs, i.e., taking into account only their denotative character, it is clear that there are relationships given by the linguistic structure of these words that could be taken into account in the relationship between the terms, but that have not been introduced in the model. If we consider the words “culture” and “acculturation”, even if a person does not know the meaning of the word “acculturation”, that person is unlikely to think that it denotes a new type of carrot that can be found in the local market: he or she is likely to think that it is something related to culture. However, it is difficult to introduce such information a priori in a relational model such as the one we propose. Again, mathematical description is restricted by its own formal limits.

4.2. Word Neighborhoods in a Text

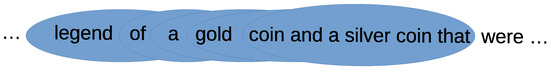

A common criterion to know the intensity of the relationship between words is given by the number of interactions between them, defined as a measure of how two given words appear close to each other in texts written in a given language. To quantify this relationship, we can use the following mechanism: given a natural number two words, and , in a text are understood to be related by proximity if there are fewer than words between and . Let us show how this idea can be formalized by means of a set-word embedding, and what the natural distance and the semantic index given by the model mean (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sequences s in a text for The last circle marks the sequence , which contains the set {“coin”, “and”, “a”, “silver”, “that”}, and the previous one, , contains the words {“gold”, “coin”, “and”, “a”, “silver”}.

Fix a specific text with N words and define the set S of all the sequences s of size of consecutive words in it, indexed by its order of appearance; it can be easily seen that Fix a specific set of (different) such words and write for the set of words of the sequence Define the algebra of all the subsets of S, and consider the set-word embedding that sends each noun w in W to the set of all the sequences in which w appears, that is,

that is, is the set of sequences that contain the word

Let us show how this construction works for the analysis of words in the text. Fix to be the counting measure. Following the definition, the canonical distance between two words and is given by

Note that is the number of sequences of the model that contain but do not contain and is the same, but changing by

The semantic index is given by the expression

which means the ratio among the number of sequences that contain both and and the number of sequences that contain This clearly gives a natural quantification of the interaction among and normalized by the “relevance” of in the text represented by In other words, gives a measurement of how far the term is involved in the function of as a word in the text.

For example, if both and are nouns, would be interpreted as an index of how the meaning of relates to that of in the text. Clearly, for , we obtain and the index is equal to 0 if all occurrences of the words and in the text are separated by more than words, that is, if every occurrence of is “outside the textual environment” of any occurrence of .

4.3. Scientific Documents in arXiv

Consider a set, S, of documents related to a certain topic in a scientific preprint repository (e.g., arXiv). Identify each of these documents with the set of all the words that appear in it. Take a set N of scientific terms on this topic that appear in at least one of these papers, and consider the set-word embedding which sends each word n to the set of documents in which it appears, where is the algebra of all the subsets of

The question about the terms to be analyzed is to what extent different terms appear together in the documents or, in other words, how close they are in relation to their use in the documents’ class. Note that if two terms occur together in all documents, they are inseparable in the word embedding and should be considered a single semantic entity (otherwise is not a distance).

Take, again, the counting measure. The distance indicates the size of the set of documents that either contain and not or contain and not If is small, there are no documents in which the two terms are related, so they are not connected in the semantic environment defined by the document set.

The semantic index is in this case given by

It can be easily seen that, unlike in the case of the classical Jaccard index, non-symmetry is a natural feature of relational indexes in set-word embedding models. If is a rare term in the subject we have fixed to determine the set of preprints, we can expect that it does not appear often in the documents of the fixed collection. But if every time it appears it is accompanied by , we obtain that is, indeed, relevant to the meaning of in this context, and then the index takes the value In this case, however, the inverse index might be very small if is a very common term; that is, is not relevant for the meaning of

5. Set-Based Word Embeddings Versus Vector-Valued Word Embeddings: General Set Representation Procedure

The notion of set-word embedding is primarily thought to be as simple as possible. The complexity of the model and all the features that can be added to it are supposed to be performed by means of Lipschitz functions acting on the set metric space. However, it can be easily seen that both constructions are essentially equivalent, although our set-based construction aims to be simpler. In this section, we prove an equivalence result that shows a canonical procedure to pass from a class of models to the other class, and vice versa.

The following result also provides explicit formulae for the transformation. It is, therefore, the main result of the present work, as it allows us to identify any word embedding with a set-word embedding using a canonical procedure. The main advantage of this idea is that the basic information in the set algebra model lies in the measure of the size of the shared meaning between two terms, whereas a standard set-word embedding in a Euclidean space usually occurs automatically, and there is no possibility to interpret how the distances are obtained and what they mean. Thus, set-word embeddings are interpretable, while standard word embeddings are not. We will return to this central point in the Conclusions section of the article.

In addition to its simple formal structure and the advantages of defining word embedding features as pure metric objects (Lipschitz maps, without the need for any kind of linear relation), there is a computational benefit that makes it, in a sense, better. We will explain it after the theorem. As usual, we assume that an isometry between metric spaces is, in particular, bijective.

Theorem 2.

Let W be a (finite) set of word/semantic terms of a certain language. Then, the following statements hold.

- (i)

- If is a metric word embedding into a finite metric space there is a set-word embedding into a algebra of subsets and a (non-necessarily positive) measure μ on S such that and are isometric.

- (ii)

- Conversely, if there is a finite set-word embedding there is a metric word embedding into a metric space such that and are isometric.

Moreover, every metric word embedding can be considered as normed-space-valued.

Proof.

Let us first prove (i). Consider the set of terms and the set Write We can assume that for there is nothing to prove, and for the result is trivially proved by a direct construction with a set, S, of two elements.

Number the elements of W and identify with the set which is considered to have the same metric d as Write for the metric matrix of We want to construct a measure space and a word embedding such that and are isometric.

Set the algebra of the subsets of and consider the word embedding given by

where is the word with the number We have to find a measure on S such that for That is, for Note that for all . Write T for the symmetric matrix where Let us write all the equations above using a matrix formula. Consider the matrix with for all

Write the symmetric matrix N of the coefficients that we want to determine. Take any diagonal matrix and define the symmetric matrix Note that we can write an equation that coincides with for all the elements out of the diagonal as

in which the elements of the diagonal take arbitrary values that can be used to normalize the coefficients.

Now we claim that where is the identity matrix of order Indeed, note that has all the elements of the diagonal equal to and all the elements out of the diagonal are equal to Thus,

Now, consider the equations

that give Then, and so, using that we obtain the symmetric matrix

This gives a result that is not unique, as it depends on the diagonal matrix Note that, due to the required additivity of the measure the set of all the values determine a measure which is not necessarily positive.

The proof of (ii) is obvious; take a finite measure space and a set-word embedding Suppose that we have a numbering in By definition, the set is a metric space with the distance so the map is the required word embedding.

We only need to prove that we can assume that is a subset of a normed space , and so we can define the word embedding to have values into There are a lot of different representations that can be used; probably the simplest one is given by the identification of the metric space with the Arens–Eells space , which is explained in the Introduction. It is well known (see, for example, [26], Ch.1) that there is an isometric Lipschitz inclusion given by where 0 is a (could be arbitrarily chosen) distinguished element of X, and is the molecule defined by x and Therefore, is the desired vector word embedding. Of course, given that is a finite set in the Banach space we can represent it with coordinates to obtain a vector-like representation such as the reader might identify with a usual vector word embedding. This finishes the proof. □

Remark 2.

The proof of Theorem 2 gives useful information, which is, in fact, its main contribution for the representation of word embeddings by means of subsets. It gives an explicit formula to compute, given a vector-valued word embedding i, a measure space whose standard metric space structure provides an isometric representation to the one given by Indeed, for , it is given by the formula

where Δ is a diagonal matrix with free parameters, and

This equation gives the values of the measure μ for the atoms of the class

that are represented in the symmetric matrix They can be used to compute the values of the distances between the elements of the representation,

which are given by

In the model, the diagonal matrix Δ and the metric are key elements that shape its behavior. Adjusting the diagonal entries of Δ—which work as parameters of the model—tunes the metric, modifying the relative weights of dimensions to meet specific constraints or properties. The metric defines the distance measure, guiding how distances between terms are evaluated by means of their representation as classes of subsets. Together, Δ and the construction of allow the model to adapt flexibly to problem-specific requirements, ensuring robustness and alignment with desired outcomes.

Example 2.

Take and consider the word embedding where These terms can be, for example, three nouns in a model that we want to develop, as The distance matrix suggested below is coherent with the idea that “man” is, in a sense, close to “king” (a king is a man), and “king” is close to “queen” (both belong to royalty), but, on a comparative scale, “man” and “queen” are not so close.

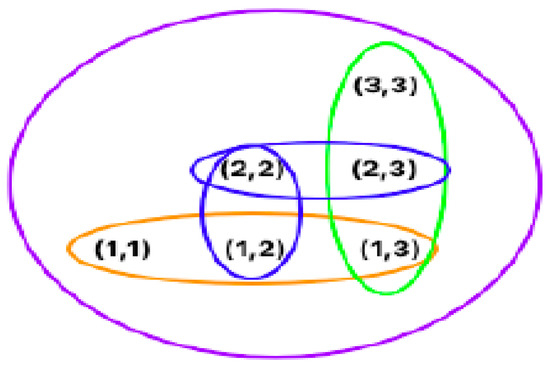

- Endow W with the metric d given by the matrix We proceed as in the proof of Theorem 2; obtain the setWe consider the set-word embedding defined as in the proof of the theorem; that is, for instance, (below for the other terms). This means, for example, that the word “king” is represented by a set of three (vector) indices, and so on. These indexes could represent different characteristics of the semantic term but, from a formal point of view, they are only distinguished indexes. Take the free parameter diagonal matrix as Then,This matrix gives the values of the measure μ for the elements of the atoms of the measure space: and so on. In the model, they give the measure (understood as weight) of the different characteristics that represent each of the atomic indices Using that to verify that the calculations coincide with the values of the original distance is straightforward. For example,whilewhich, of course, coincide with the corresponding coefficients of the original metric matrix Note that the measure μ is equal to 0 for most of the atoms, so it cannot distinguish between certain non-empty sets of the generated algebra. However, the formula of our distance defined using the set algebra separates between all the elements of the canonical set-word embedding given in this case, as we said, by (see Figure 3)and

Figure 3. Sets defining the representation of the set-word embedding.The subsets represented in Figure 3 can be understood as subsets of different features (the indices ) that allow the representation of the original semantic environment , in the sense that each subset of features represents different semantic objects with their own semantic role in the model.

Figure 3. Sets defining the representation of the set-word embedding.The subsets represented in Figure 3 can be understood as subsets of different features (the indices ) that allow the representation of the original semantic environment , in the sense that each subset of features represents different semantic objects with their own semantic role in the model. - Let us show now the same computations for a different metric matrix D such that all the distances between the three points are different. In this case, we obtain

Example 3.

Now take and Then, we have that, for the same computations as in the other examples give the following matrix defined by the values of the measure μ for the atoms of the representation, which are, in this case,

The measure matrix N is

For example,

which coincides with the coefficient of D in the position that is, Note that, according to the measure matrix the measure μ is not positive: there are atoms for which the measure is negative, and others for which the measure equals However, the standard formula for the associated set distance gives a proper distance matrix, as it coincides with the metric matrix

It should be noted that we need the most abstract notion of set-word embedding to obtain that, in general, any (metric) word embedding can be written as a set-word embedding: the measure obtained for the representation is not necessarily positive, but it has to be positive for all the sets defined as symmetric differences of the elements of the algebra in the range of the representation that is, for the elements such as for which we need positive measure evaluations to obtain a suitable metric.

Note also that the standard application of the procedure, provided by the equations explained above, lies in the identification of semantic terms with elements of a algebra of subsets. The size of such subset structures increases exponentially with the number of semantic terms, which could compromise the scalability of the method. This means that it might be necessary to imagine a representation procedure using subsets for each specific problem, which would detract from the generality of our technique.

Remark 3.

Direct applications of word embeddings, such as word similarity and analogy completion, should be approached from a different point of view than in the case of vector-valued word embeddings. In the case of word similarity, the linear space underlying the representation facilitates the task, as the scalar product inherent in Euclidean space provides the correlation as well as the cosine. In our case, however, a different approach is necessary, since, a priori, there is no associated linear space other than the one given by our representation theorem, which is often too abstract, as we just said. But it is possible to obtain a quantification of the notion of word similarity by relating to each word the calculated semantic index with respect to the other semantic terms of the model, thus constructing a vector whose correlation with any other vector associated with another word can already be calculated. Again, the advantage of our method compared to embedding words in a Euclidean space is interpretability: each coordinate of the vector thus constructed represents the extent to which the word and any other term in the model share their meaning, in the sense indicated by the semantic index used. Analogy completion could also be better performed in the case of embeddings of sets of words, as the representation of the word and any other term in the model share the same meaning, in the sense indicated by the semantic index used. Analogy completion could also be better realized in the case of word-set embeddings, since the representation is based on the extent to which two terms share their meaning, and then the logical relationships are supported by the mathematical formalism.

6. Discussion: Comparing Multiple Word Embeddings with the Set-Word Embedding in an Applied Context

In this section, we use the tools developed through the paper to obtain a set-word embedding related to the semantic indices (semantic projections) that are explained in Section 3 (Definition 2). We follow the model presented in Section 4.3 to define a word embbeding associating with each term a class of subsets of documents in which the word appears. To facilitate reproducibility for the reader, we opted to use the Google search engine for the calculations rather than relying on a scientific document repository, which may have access restrictions. For this application, we utilize the results provided by Google searches, meaning that the measure of the set representing a given term corresponds to the number of documents indexed by Google that contain the word in question.

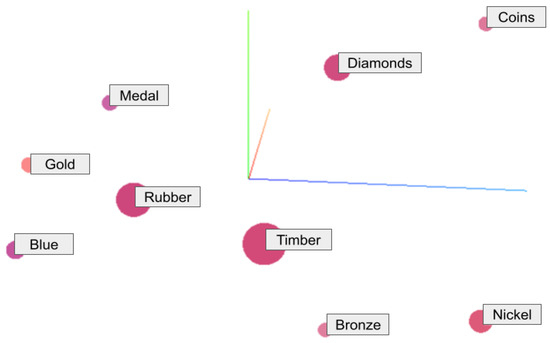

Let us fix the term “gold” and consider the set of words given by the Word2vec embedding (Figure 4). As usual, the associated vector space is endowed with the Euclidean norm. To compare our word-set embedding with this one, we use as working environment the 10 words that are close with respect to the distance provided by the embedding to the fixed term, including “gold”. The terms are {gold, silver, medal, blue, reserves, coin, rubber, diamonds, tin, timber}, and the distances to the term “gold” can be found in the second column of Table 1.

Figure 4.

A 3D representation of the embedding of the closest words to the term “gold”, according to the Euclidean distance, using Word2vec Google News (71291x200) (http://projector.tensorflow.org/ (accessed on 3 January 2025)).

Table 1.

Table with the words, the values of the Euclidean distance with the word “gold”, and the corresponding values of the elements of the set-word embedding.

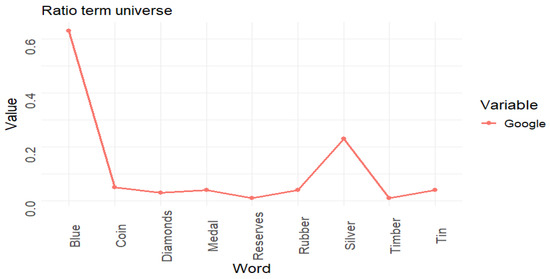

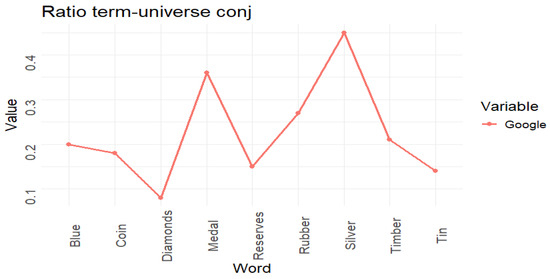

The other values of Table 1 complete the information to compute the metric provided by the set-word embedding using Google search. Following the theoretical development explained in Section 3, the basic elements to understand our model are the semantic indices and which are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively.

Figure 5.

Semantic indices for gold ().

Figure 6.

Conjugate semantic indices for B for each of the selected words.

Recall that we have and using the formulas

given by Lemma 1, we can compute Table 1. In this table, the measures are written in billions (1,000,000,000). To simplify calculations, we will divide by this number in the distance definition computed below, reducing unnecessary complexity.

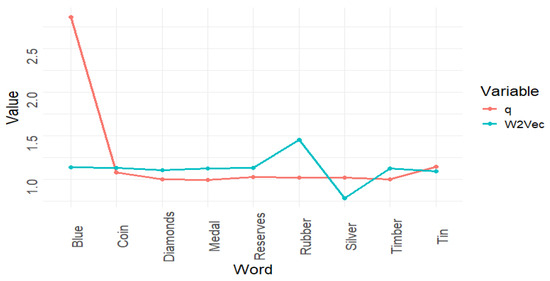

To facilitate the comparison of the metrics, in Figure 7 and Figure 8 we divide the distance associated with the set-word embedding by eight. Obviously, this change of scale does not affect the properties relevant to the comparison. As can be seen, the distributions obtained for the two metrics are similar, although there are significant differences. Figure 8 shows the same information as Figure 7, but in it we have removed the term “blue” to facilitate the comparison of the values of the rest of the terms, as its large values disturb the overall view.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the results provided by Word2vec and the set-word embedding defined by Google search for the term “gold”.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the results provided by Word2vec and the set-word embedding excluding the term “blue” for a better visualization.

The primary reason for these differences is the influence of context. Traditional early word embeddings rely on a fixed, universally applicable mapping of semantic distances, while the set-word embedding allows the incorporation of contextual information derived from the large variety of documents indexed by Google. Although the boundaries of this contextual information are not entirely clear, it is evident that the relationships between semantic terms are influenced by the volume of information available across internet documents. This explains, for instance, why the term “blue” is quite distant from “gold”, as the various meanings of “blue” are not statistically related to the meaning of “gold” in a significant proportion.

The term “medal” is closer to “gold” than to “silver” in the information repository queried by Google. This makes sense when we consider that “gold medal” is a much more prevalent phrase on the internet, highlighting common usage patterns. In contrast, while gold and silver are similar in their inherent nature as metals, their association in language is less frequent compared to the popularized use of “gold medal”. Hence, usage, rather than inherent similarity, drives this result. The same can be argued regarding the terms “reserves”, “rubber”, or “coin”. The relationships provided by the word-set embedding with the other words, “diamonds”, “tin”, and “wood”, are more conventional, as can be seen by comparing them with the results provided by Word2vec.

6.1. Advanced Models

Let us introduce now in the discussion other word embeddings that have been designed following different ideas. We now compare some advanced word embedding models, focusing on their ability to capture semantic relationships between precious metals, other commodities, and related terms. The evaluation includes performance metrics and similarity analysis using cosine similarity and L2 distance. As this information is quite exhaustive, we preferred to move some of it to Appendix A.

Microsoft Research’s E5 models, including E5-small (384 dimensions) and E5-base (768 dimensions), represent significant advances. Trained by contrastive learning on diverse datasets, they are versatile in their applications. We also examined Microsoft’s MiniLM models, which offer effective alternatives through knowledge distillation. The L6 variant emphasizes speed, while L12-v2 offers deeper semantic understanding. Finally, ByteDance’s BGE-small model, optimized for retrieval tasks, combines contrastive learning and masked language modeling to deliver high performance in a compact form factor. These models offer different trade-offs between efficiency and semantic accuracy. More information can be found in Appendix A (see the bibliographic references to related papers in this appendix).

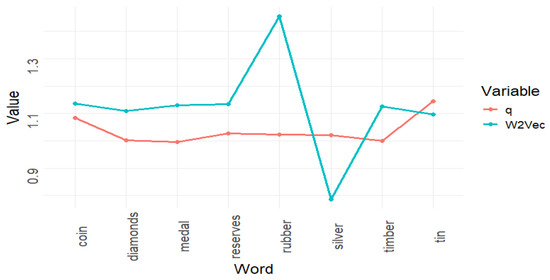

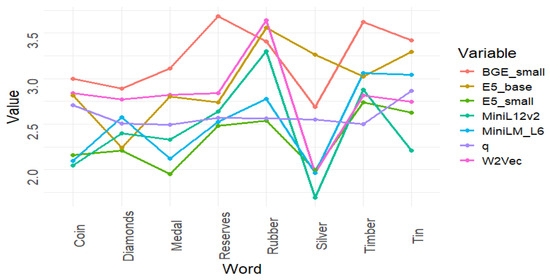

Table 2 provides the results of the distances of the term “gold” to the other terms using these word embeddings, which can be compared with the results given by our set-word embedding and by Word2Vec. Figure 9 gives a clear picture of how these other embeddings behave in comparison with the previous ones. In order to compare in a better way, all the models are normalized to have an average value of about eight.

Table 2.

L2 distances of the term “gold” to the other terms using the word embeddings E5-small L2 distance, E5-base L2 distance, MiniLM-L6 L2 distance, BGE-small L2 distance, and MiniLM-L12-v2 L2 distance.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the results provided by Word2vec and the set-word embedding including the other word embeddings of Table 2.

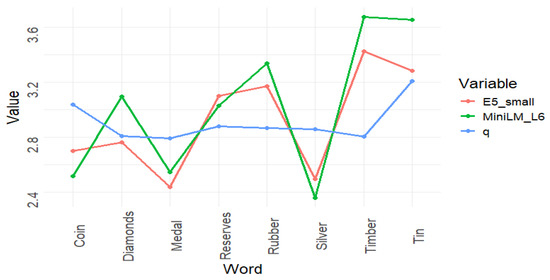

Figure 9 presents the results of the seven models included in the comparison, with the set-word embedding highlighted in purple. To facilitate a clearer comparison, we scaled the results by appropriate factors to ensure that the representations are centered. In Figure 10, we show only two selected models alongside the set-word embedding for a more focused analysis. As observed in both figures, the set-word embedding produces smoother results overall (the example is chosen for this to happen), although it still follows the primary trends exhibited by the other models, albeit with some slight deviations.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the results provided by the set-word embedding and the models E5-small and MiniLM-L6, which are the ones that have a similar distribution.

For the three models selected for Figure 10 (set-word embedding, E5-small, and MiniLM-L6), the trends are more clearly visible, with the set-word embedding shown in purple. This allows a more focused comparison among these specific models, highlighting the distinctive patterns in their performance.

As can be seen, the comparison of the models in this section reveals that, while they all produce different outputs, the variations are not substantial, and some common trends emerge, especially after adjusting the scale for better visualization. The set-word embedding provides a more stable result compared to the other models. However, when considering the combined contributions of the other models, the set-word embedding generally aligns with the overall averages of their performance.

6.2. Remarks on the Comparison of Semantic Models

In summary, the results of this analysis suggest that if the meanings of words are derived from their relationships within a given semantic environment, those meanings fundamentally depend on the measurement tool used to establish these connections. In fact, it seems more practical for many applications to assume that no isolated relationships between terms fully define a word’s meaning. These relationships are always shaped by context, and—this being the main theoretical contribution of this paper—by the measurement tool used to uncover these connections.

Let us give some hints about possible future applications of our ideas. Let us provide some observations on how other commonly used NLP tools can be adapted to our formal context. Techniques such as prompt engineering and few-shot learning, which are fundamental to improve the performance of linguistic models, could be effectively integrated with set-word embeddings. Prompt engineering [30,31,32] involves crafting specific instructions or queries to guide models like GPT toward generating precise and contextually relevant responses. In our context, the construction of these prompts could be informed by the semantic indices used in set-word embeddings, with logical relationships between terms directly translating into formal properties of the model, thereby simplifying the prompt creation process. A similar approach applies to few-shot learning [33,34], which enables models to perform tasks with minimal examples by leveraging their generalization capabilities within the context of the provided prompt.

Additionally, set-word embeddings can serve as a foundation for developing new procedures for LLM-based semantic search (see, for example, ref. [35] and the references therein). This advanced search methodology employs large language models (LLMs) to move beyond traditional keyword matching, identifying implicit relationships and deeper meanings in text. By incorporating set-word embeddings as the underlying semantic framework, this approach could achieve greater interpretability and semantic precision compared to other word embedding options. The integration of these interpretable embeddings would enhance the relevance and contextual accuracy of retrieved information, offering a more robust and insightful framework for semantic search.

Regarding the limitations of the proposed set-word embeddings, we have shown that our procedure is general from a theoretical point of view, in the sense that it covers all situations where standard vector word embeddings are applied (Theorem 2). However, computing the equations to relate both models could be computationally expensive. As can be seen, the size of the matrices involved in the computations could be huge in real cases, and the number of computations could increase exponentially, since in the basic elements of the model are subsets of the initial set of indices, thus increasing with the power of the original set of terms This problem could also carry over to the usual applications of our model, as the construction of the power set underlying the representation could break the potential scalability of the procedure. Other methods of identifying semantic terms with elements of a algebra of subsets would have to be used, adapting them to specific contexts, as shown in the examples presented in Section 4. This could restrict their use, as a concrete representation would have to be invented for each application. The development of alternative systematic approaches for defining set-word embeddings depending on the context, along with their analysis and comparison with existing word embedding techniques, represents a key focus of our future work.

7. Conclusions

Set-word embeddings represent a more general approach—though fundamentally distinct from standard methods—from the outset in defining word embeddings on structured spaces. Rather than relying on a linear space, which can sometimes introduce confusion in the representation, the set-word embedding associates each term with a subset within a class of subsets, S, where the class itself has some structural properties. This set-based approach offers a more flexible and intuitive framework for capturing semantic relationships. Furthermore, this original set can always be embedded within a more robust set structure, such as the topology generated by This allows the application of topological tools to better understand the embedding process. In this paper, we illustrated the case where S is embedded in the algebra generated by S itself. In this context, a canonical structure can be established, first treating it as a measure space and subsequently as a metric space. The embedding representation, then, is viewed as an embedding in a measure space, offering a new perspective on word embeddings that allows for richer and more flexible analysis.

This set-based embedding framework not only enables a deeper understanding of the structural properties underlying word representations but also provides a means to apply advanced mathematical techniques, such as measure theory and topology, to the problem. By leveraging these tools, we can gain insights into the continuity, convergence, and general behavior of word embeddings in a more formalized and rigorous way. This approach also opens the door to the exploration of new types of embeddings, which could potentially capture more complex relationships between words and their meanings.

The main limitation of the proposed technique lies in its practical performance, particularly in terms of scalability. Enhancing the algorithms for real-time applications may be challenging. However, there is an advantage over other methods: the computation of distances between two semantic terms can be performed independently of the other coefficients in the metric matrix. This is because the semantic indices are defined using external information sources that are specific to each pair of terms. Therefore, if only a small subset of distances is needed, the method could remain competitive, even in the context of large and demanding information resources.

Finally, it is worth noting that this methodology offers a flexible way of defining word embeddings and introduces a shift in the way we understand them. As demonstrated in the example in Section 6, the widely accepted assumption in NLP that context shapes word relationships can be taken a step further from our perspective. Not only does context influence the relational meaning of words, but the measurement tool used to capture these relationships also defines a specific way of interpreting them. Set-word embeddings provide access to a variety of these measurement tools: for instance, each document repository creates a relational structure that reflects how terms interact within that particular context. The distance , determined by a given measure on the set-word embedding, thus defines a unique interpretation of the words’ meanings.

Let us conclude the article by mentioning what is possibly one of the main benefits of the proposed set-word embeddings. Unlike the vast majority of word embeddings, the set-word embedding method offers clear advantages in terms of interpretability and explainability compared to contemporary methods. Although modern language models often rely on post hoc explanation methods such as feature importance, saliency maps, concept attribution, prototypes, and counterfactuals [36], the set-based approach provides inherent interpretability through its fundamentally distinct mathematical foundation, where each term is associated with a subset within a class of subsets, S, which can be embedded in a measure space and subsequently as a metric space. This transparent mathematical structure addresses the lack of formalism in terms of problem formulation and clear and unambiguous definitions identified as a key challenge in XAI research [37]. The method’s representation through struc- tured spaces rather than traditional linear space, which can sometimes introduce confusion, provides a clearer framework for semantic analysis, contrasting with current embedding approaches that face faithfulness issues and often require complex post hoc explanations [38]. Furthermore, as noted in this article, the topology generated by S allows the application of topological tools to better un- derstand the embedding process, offering a level of theoretical interpretability that aligns with the call for more attention to interpreting ML models [37]. This mathematical rigor addresses the need for faithful-by-construction approaches to model interpretability, though with more solid theoretical foundations than some current self-explanatory models that fall short due to obstacles like label leakage [38].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F.d.C. and E.A.S.P.; methodology, E.A.S.P.; software, C.A.R.P.; validation, C.S.A.; formal analysis, C.A.R.P. and E.A.S.P.; investigation, P.F.d.C., C.A.R.P. and E.A.S.P.; data curation, C.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.S.P. and C.A.R.P.; writing—review and editing, P.F.d.C.; visualization, C.S.A.; supervision, E.A.S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Generalitat Valenciana (Spain), grant number PROMETEO CIPROM/2023/32.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of Instituto Universitario de Matemática Pura y Aplicada and Universitat Politècnica de València.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This paper presents selected examples of state-of-the-art word embedding models, focusing on their ability to capture semantic relationships between precious metals, commodities, and related terms. The evaluation includes both performance metrics and a detailed similarity analysis using cosine similarity and L2 distance measures.

Let us give first an overview of the models we present in the Discussion section of the paper. The E5 family of models, developed by Microsoft Research [39], represents a significant advancement in text embeddings. We evaluate both E5-small (384 dimensions) and E5-base (768 dimensions). These models were trained using contrastive learning on diverse datasets including web content, academic papers, and domain-specific documentation. MiniLM models (L6 and L12-v2) are lightweight alternatives developed by Microsoft [40]. Using knowledge distillation techniques, they compress BERT-like architectures while maintaining competitive performance. The L6 variant emphasizes efficiency, while L12-v2 provides more nuanced semantic understanding. BGE-small, developed by ByteDance [41], is optimized for efficient retrieval tasks. It employs a combined training strategy of contrastive learning and masked language modeling, achieving strong performance despite its compact architecture. The results are shown in the following subsections.

Appendix A.1. Performance Metrics

Table A1 shows the computational performance of each model. The metrics include model loading time, average embedding time per input, and embedding dimensionality.

Table A1.

Model performance comparison.

Table A1.

Model performance comparison.

| Model | Load Time (ms) | Avg Embed Time (ms) | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| E5-small | 3015.22 | 177.77 | 384 |

| E5-base | 4201.97 | 255.57 | 768 |

| MiniLM-L6 | 1688.44 | 112.07 | 384 |

| BGE-small | 2864.15 | 233.54 | 384 |

| MiniLM-L12-v2 | 4450.30 | 213.06 | 384 |

Regarding the performance characteristics of the models, it can be said that MiniLM-L6 demonstrates superior efficiency with the lowest load and embedding times. On the other hand, E5-base requires significant computational resources but provides higher dimensionality. MiniLM-L12-v2 shows unexpectedly high load time despite having similar architecture to L6, while BGE-small maintains balanced performance metrics.

Appendix A.2. Similarity Analysis