1. Introduction

Emotions are universal, ubiquitous, and have a large impact in all the aspects of our lives. Emotions shape our relationships and define how we interact with family members, friends, coworkers, and other people that we meet during our lives. Experiencing an emotion allows us to evaluate and perceive a concrete situation following a pre-existing set of cognitions, attitudes, and beliefs about the world.

Emotional competence is a basic ability that characterizes emotionally intelligent individuals. Having emotional competence implies being able to establish healthier relationships and to deal with adversities. Individuals without emotional intelligence do not have the ability to master their emotions, and this means that they might be unable to communicate properly and, therefore, be led to act inappropriately due to a misunderstanding of situations. Hence, emotional intelligence is a significant competence for professional success as it depends on how emotions are dealt with in terms of the ability to influence, communicate, collaborate, solve conflicts, and work in a team.

To some extent, it is possible to improve one’s emotional competence or, at least, some of the inherent aspects such as emotional self-consciousness, emotional self-control, self-motivation, empathy, and social skills. The League of Emotions Learners (LoEL) project promotes this development and provides a bridge to overcome the emotional intelligence gap between the younger professional generation and the organizational context in companies. It mainly seeks to empower the youth so that they can express and communicate emotions, are aware of the cultural factors behind the expression of emotions, and can acknowledge the importance of the media channels on the shaping of an emotional message. By using the project outcomes, young people are expected to be able to identify, understand, manage, and communicate their own emotions and other people’s emotions.

1.1. Emotional Intelligence

Emotions are biologically based states translated into thoughts, feelings, and behavioral responses that are brought on by neurophysiological changes [

1,

2]. Emotions work for us in the sense that they guide our behavior and our thinking process, particularly when a rapid response is needed to sudden (sometimes, critical) situations. They also help to relate to other people, manage expectations, and understand and respond to life challenges. As mentioned before, emotions are normally triggered from an occurrence and their perception, which can be conscious or unconscious. The occurrence can be external or internal, current, past, or future, real or imaginary. There is an innate mechanism that values the stimuli that reach our senses and generates the corresponding emotions. If the happening is assessed as positive, it is perceived as progress toward wellbeing and generates positive emotions. On the contrary, if the happening is assessed as negative, it generates negative emotions.

Individuals react differently to similar situations as emotions change according to how everyone feels and sees the world and how they interpret the actions of others. We evaluate what is happening in a way that is consistent with the emotions we are feeling, thus justifying and maintaining the emotions. Moreover, emotions produce changes in the part of our brain that mobilizes us to deal with what has set off the emotion. Emotions also cause changes in our automatic nervous system (which regulates our heart rate, breathing, sweating, etc.), preparing us for different actions. Facial expressions, as part of this mechanism, do not just communicate emotions, they also increase those that a person is feeling and send signals to the body to issue a consistent response.

The identification of emotions and, particularly, the basic (or most important) ones has been the subject of a wide and extensive debate in the psychological community. In his revised proposal, Ekman proposed what is nowadays the most used model (even if Eckman himself has somehow moved on from this approach) that includes six basic emotions: sadness, disgust, happiness, fear, surprise, and anger [

3]. The other emotions (more than 50 already identified) such as shame, revenge, and hope are linked to these six basic emotions. Ekman’s view included the notion that emotions are discrete, measurable, and physiologically distinct as the subjective and physiological emotional experiences matched the distinct facial expressions.

Emotional intelligence is the ability to distinguish and manage emotions and to use this knowledge to manage one’s thoughts and actions. It is “the ability of a person to monitor one’s own and other people’s emotions, to discriminate between different emotions, to label them appropriately, and to use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior” [

4]. It is also the ability to recognize other people’s feelings and one’s own and to be able to motivate and handle properly the relations that we have with other people and with ourselves. Goleman proposed that an emotionally intelligent person should be able to differentiate between distinct emotions and to devise an accurate and effective plan of action to respond to different situations and scenarios [

5]. He further detailed that an emotionally intelligent person should be an effective handler of others’ emotions by manipulating body language and conversations to manage and regulate others’ emotions in a favorable direction to the goals of the parties.

Emotional competence therefore is defined as a set of knowledge, abilities, and attitudes that allows one to be aware, understand, express, and manage appropriately an emotional phenomenon. Schutte, Malouff, and Thorsteinsson argued that a person is competent in the perception of emotions if they can recognize emotions from the voice and facial cues of others, as well as be aware of one’s emotional state and reactions [

6]. This competence increases the personal and social wellbeing through emotional conscience, emotional regulation, emotional autonomy, social competences, and wellbeing and social abilities.

Emotional conscience is the ability to be aware of one’s own emotions, to be able to identify and classify emotions, to use emotional vocabulary and expressions, to understand other people’s emotions, and to be aware of the interaction between emotion, cognition, and behavior.

Emotional regulation allows one to understand that the internal emotional status might be different from the external expression, to regulate one’s emotional expression, to face challenges and conflict situations and, finally, to be aware and capable of generating positive emotions.

Emotional autonomy provides a positive image about oneself (self-esteem), allows one to be involved in diverse activities of daily life, to be capable of making and maintaining social relationships, to take responsibility of one’s actions, to have a positive attitude, and to face adverse situations.

Social competence allows one to manage basic social skills, to respect others, to practice receptive communication, and to take responsibility for one’s actions.

Wellbeing and social abilities involve the ability to set-up goals, to search for help and resources, to identify the need for help, to develop an attitude of awareness of the rights and duties as a citizen, and to create optimal life experiences.

Emotional competence is especially important for teenagers and youth, in general. During this stage of life, young people will move away from their families and will be closer to their peers and to the labor market. This can be a difficult time especially if the young person cannot understand their own or other’s emotions. Young people who develop their emotional intelligence early become more empowered, are more aware and assertive, and are able to solve problems more easily, and they cope better with tough/stressful situations at work.

1.2. Emotional Intelligence in the Professional Context

Emotions are naturally present in the professional world. Knowing how to recognize one’s emotions and to understand how they affect oneself and others can contribute to better manage the adversities of life and to deal with unforeseen events that happen in daily professional life. Being emotionally intelligent allows an employee to perceive, understand, utilize, and manage emotions effectively in a professional context [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Organizations consider emotional intelligence as an important skill, due to its significant impact on the various aspects of the business community, especially employee development, performance, and productivity [

11]. The Emotional Quotient (EQ) has been included as a factor for hiring employees, together with the Intelligence Quotient (IQ), academic credentials, and work experience [

12]. Emotional intelligence has a direct association with employee performance and professional success [

10,

13,

14,

15]. Having emotional control is essential to maintain a positive and adequate professional posture, and knowing how to deal with emotions and different personality types in the professional environment is vital to a successful career. It can also improve the emotional wellbeing of all colleagues in the professional environment. Additionally, it improves the quality of the services that the organization itself provides as it improves the relationship with clients, favors employee’s loyalty, prevents conflicts, and gives positive solutions to conflicts.

2. League of Emotions Learners

The League of Emotions Learners (LoEL) project aims to empower young people to develop their emotional competence, to be able to identify and express self-emotions, and to establish successful online and offline communication. The project was particularly concerned with professional environments and, as such, had five main objectives:

To develop empowering training resources that allow young people to identify the origin and nature of the emotions.

To facilitate a diverse set of activities that combines real digital communication methods and channels with work and personal environments.

To disseminate linguistic expressions that express basic emotions in different cultural backgrounds.

To teach appropriate verbal and gestured indicators to send effective messages in negotiation and conflict situations.

To provide enterprises and organizations that work with young people with a motivating training approach.

The project targeted young people and youth trainers that could benefit from the use of the results in their personal and professional lives, by becoming more aware of their emotional intelligence, being able to recognize the benefits of managing one’s emotions, and knowing how to express emotions and how to communicate through videos, pictures, and audio. Moreover, they can benefit by knowing how to discover how new technologies and their own channels and signs can shape communication and can be used to express emotions.

The LoEL approach brought together key aspects that, normally, are not interrelated in a training process: the importance of language in the identification and expression of emotions and the recreation of professional scenarios though learning by doing and gamifying strategies adapted to the business world.

2.1. The Guide for Youth Worker

The first result of the project was a set of ideas, resources, and examples addressed to the youth trainers to support them in their work with the young collective. These materials were created with the objective of providing these professionals with game-based and nonformal learning methodologies focused on emotions’ identification and management. The methods and contents are not only transferrable from the online to the offline scope, but also from the informal and nonformal to formal education, so youth trainers and educators can produce innovative programs. This result was called the Guide for Youth Workers and the offered practical tools allow youth trainers to facilitate learning environments where emotional competence development is the core topic. The guide also explains the LoEL pedagogical concept and approach and explains how to use and replicate it.

2.2. The LoEL App

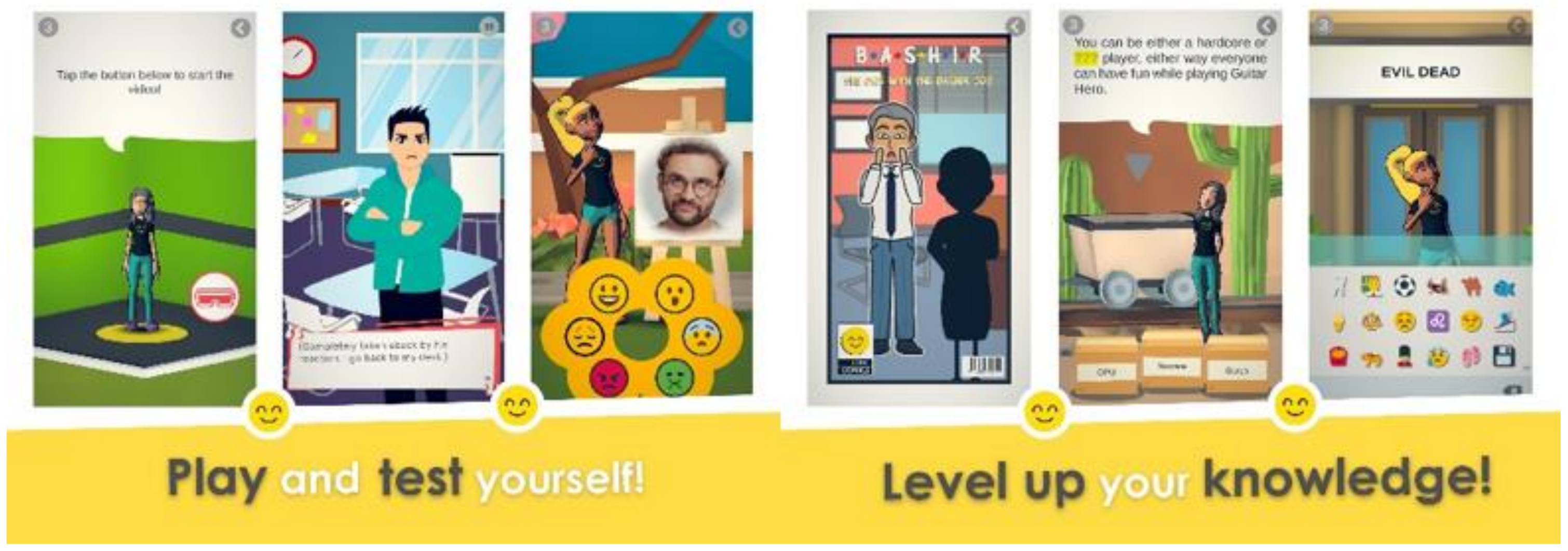

Communication has evolved and changed, and nowadays, digital audiovisual communication has gained extreme relevance. Young people are normally digital natives, that is, they grew up in close contact with computers, the internet, video game consoles, mobile phones, social media, etc. According to different studies, children now receive their first phone at the age of 10 and start interacting in social networks at the age of 14. Additionally, they frequently play with digital devices such as consoles and smartphones. This means they interact with digital audiovisual material from childhood, and this is their preferred way to connect to the world and to express emotions. Therefore, it is important to be aware that, for some people, it is much easier to express emotions using other channels rather than talking. Accordingly, the League of Emotions Learners tool (

Figure 1) was conceived as an interactive mobile app (currently available from the Google Play Store—

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.virtualcampus.loel and Apple AppStore—

https://apps.apple.com/app/id1501537657, accessed on 29 July 2021) designed to empower young people to be able to identify, manage, communicate, and understand their own and other people’s emotions.

The LoEL app implements innovative gamified educational practices that include specific activities based on the digital habits of young people. This combination of digital content in the form of a Serious Game available through a mobile platform is highly effective for the addressed target group, measured by their ability to translate the acquired competence in real tasks [

16]. Serious Games, defined as games designed with a serious purpose [

17], are immersive and motivating due to their embedded enjoyment and emotional gratification [

18], and they build training environments that allow the acquisition of knowledge, experience, and professional skills through the simulation of different situations and contexts [

19,

20], which can be well adjusted to the LoEL target group [

21]. Therefore, the app design followed a set of requirements:

Designed as a digital mobile tool as the best option considering the target group (young people). The visual design of the app also took into consideration this target group, as it can be seen in

Figure 2.

Designed to develop emotional intelligence skills and to contribute to increased theoretical knowledge and, through the types of games and scenarios contained, to enhance the development of practical interaction skills in real professional contexts.

Designed to increase sensitivity toward intercultural communication in professional contexts and interpersonal interaction.

Designed to increase the ability to establish a healthy relationship between employer and employees, an extremely important factor for young people who are recently in or will enter shortly the labor market.

Designed to help identify and express self-emotions and to establish successful communication with others both in online and offline forms.

Designed to increase the awareness of the limits and potential of digital communication.

The LoEL App integrates resources and activities that explore emotional intelligence in different ways:

EMOTIONS BOX is a multilingual dictionary of emotions, with the definitions and examples for the 50 most easily identifiable emotions (divided in basic and secondary emotions).

EXPRESS YOURSELF provides different games to test and develop the players’ ability to express themself. Examples of the included games are:

- ∘

Identifying emotions based on a definition.

- ∘

Identifying emotions in images (

Figure 3).

- ∘

Identifying images that represent an emotion.

- ∘

Asking the user to show a specific emotion.

- ∘

Completing a comic story, where users must create the correct dialogue lines for a proposed narrative focused on a specific emotion (

Figure 3).

- ∘

Asking the user to identify emoticons based on the name of a movie/song and vice versa (

Figure 3).

- ∘

Filling-in the blanks exercises with sentences that use common jargon terms.

- ∘

Identifying emotions present in short video clips (

Figure 3).

- ∘

Identifying emotions present in idiomatic expressions.

EMOTIONAL ORGANISATIONS is an activity that puts the player roleplaying and practicing how to manage emotions in professional backgrounds through simulated scenarios (

Figure 3). These activities are classified in four areas that are essential for the management of a company’s emotional intelligence: ability to control emotions, ability to motivate oneself, recognition of other people’s emotions, and control of relations.

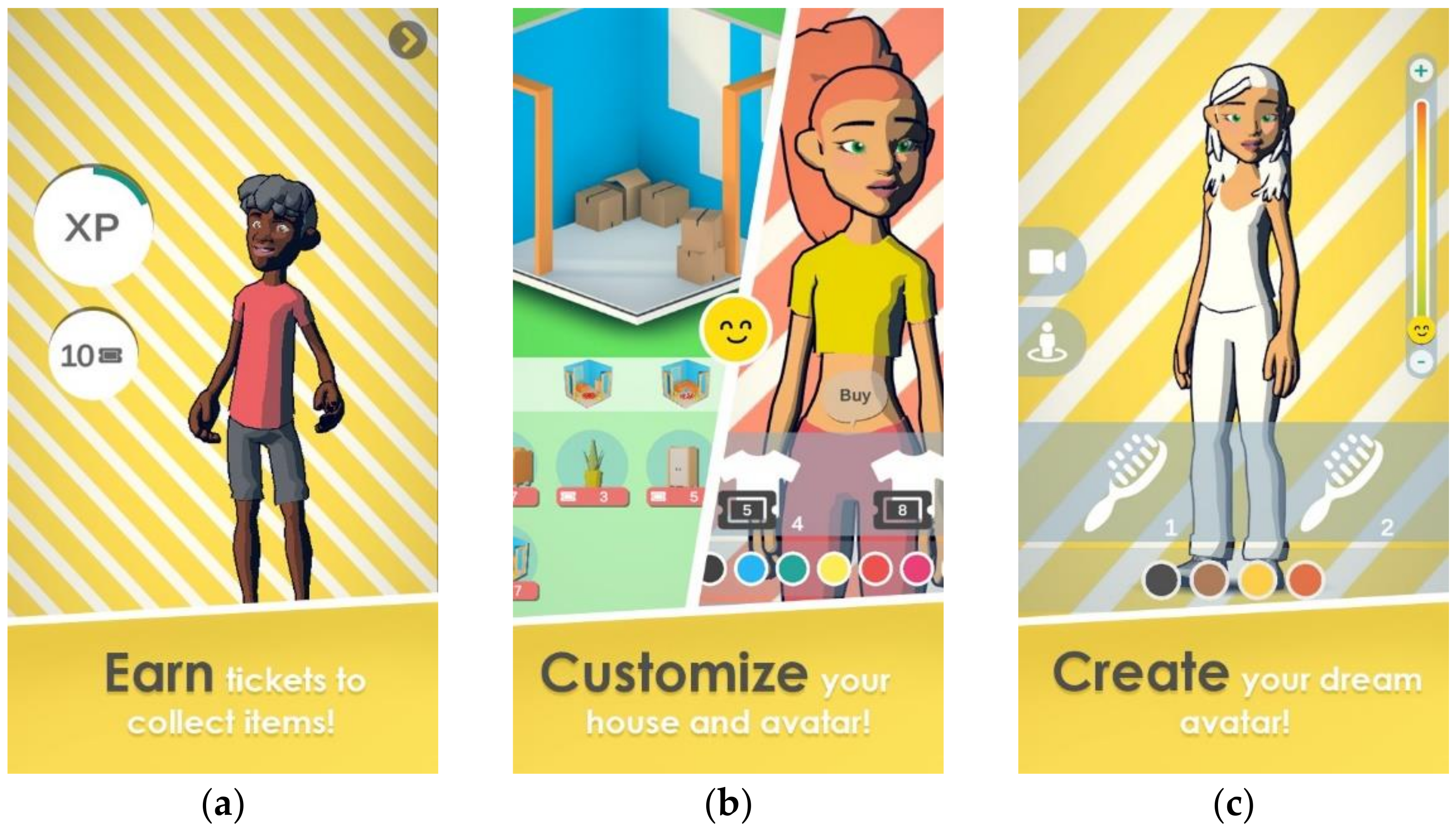

The app includes a difficulty progression system that moves the players through different levels of complexity. Currently, there are 4 different levels and, following feedback from the users, the progression, based on experience points, follows a logarithmic approach. That means that users can move quickly from the first level to the second level, need more points to move to the third level and even more points to get to the final level. The difference between levels is related to the addressed emotions (just the basic ones in the first level and then moving to the secondary ones in the other levels) and to the available types of games (more immediate games such as identifying emotions in photos in the first level and more complex games, such as the organizational scenarios, in the last level). Some game aspects such as the number of experience points and tickets received in a game and the available customizable items also depend on the level.

To allow a better identification between the user and the game, the players can create their own avatar and customize it with a set of accessories or elements (skins, objects, pets …). While playing the game, the players collect tickets that allow them to further customize their avatar and home (

Figure 4).

The app is available in 5 different languages, which of course implies a large degree of localization due to the cultural aspects related to language, signs, and emotions.

3. Results

The testing of the app followed a standard approach with alpha, beta, and piloting (gamma) stages. Alpha testing was carried out by internal staff of the involved organizations; beta testing was conducted with youth and youth workers in the involved partner countries: Spain, Portugal, Italy, UK, and Estonia; finally, piloting was conducted with a large number of users from all over Europe.

Alpha testing provided mostly a qualitative set of comments that allowed one to improve the ticketing and difficulty/level system, the graphical design of the app, and the design of the games. An important aspect was the feedback that should be provided to the user to render the development of the emotional competences more effective.

Beta testing was conducted with 110 participants, external to the LoEL consortium, mainly youth trainers (59.6%) and students (10.1%), spread evenly between the involved countries. The testing stage provided quantitative and qualitative feedback concerning the usability, game experience, and effectiveness in emotional competence development.

Here, 90% of the testers found the features of the app with ease and only three participants were not able to interact with the app. The interaction features of the app were therefore rated very high (x = 4.2) on a 5-point scale. The content was also rated highly (x = 4.1) and the transferability of the knowledge to real life was scored 3.7. More than 75% of testers thought that the app promoted knowledge and understanding of emotions; 67% of the testers thought that the app provided relevant information for people who work with youth; 64% of them also thought that the app provided competences for emotion handling; 65% of the users would use the app again.

The comments about the app were quite diverse. They complimented the idea of putting emotional education into a game and the originality of the content and the connectedness to real life. They mentioned the high number of games, the nice interface, and the interactivity of the app. Some liked to earn the coins and refurbish their room. They said that it was easy to use and attractive to young people. The game elements were well implemented, the graphics, sound, and music were catchy and effective, and they loved the use of primary colors and the wide range of options when creating an avatar.

A few participants thought that some games were too hard and that it was difficult to progress in the game, especially in the beginning. One trainer said that: “I like it very much because it actually gives you the opportunity to create a session on it. You can start a discussion on emotions and on how they affect people’s reactions. You can organize different activities providing the app to the participants. There are different levels that allow you to improve and try new games” and another teacher said that: “I liked the challenges it gives you to unlock other games and the content such as Jargon Words, for a teacher as me are useful working with my students to learn even more their words”. Suggestions for improvements were mostly about user friendliness and the elements of the user interface. In addition, some comics were hard to read because of the font/animation. Some changes to the progress system were also suggested.

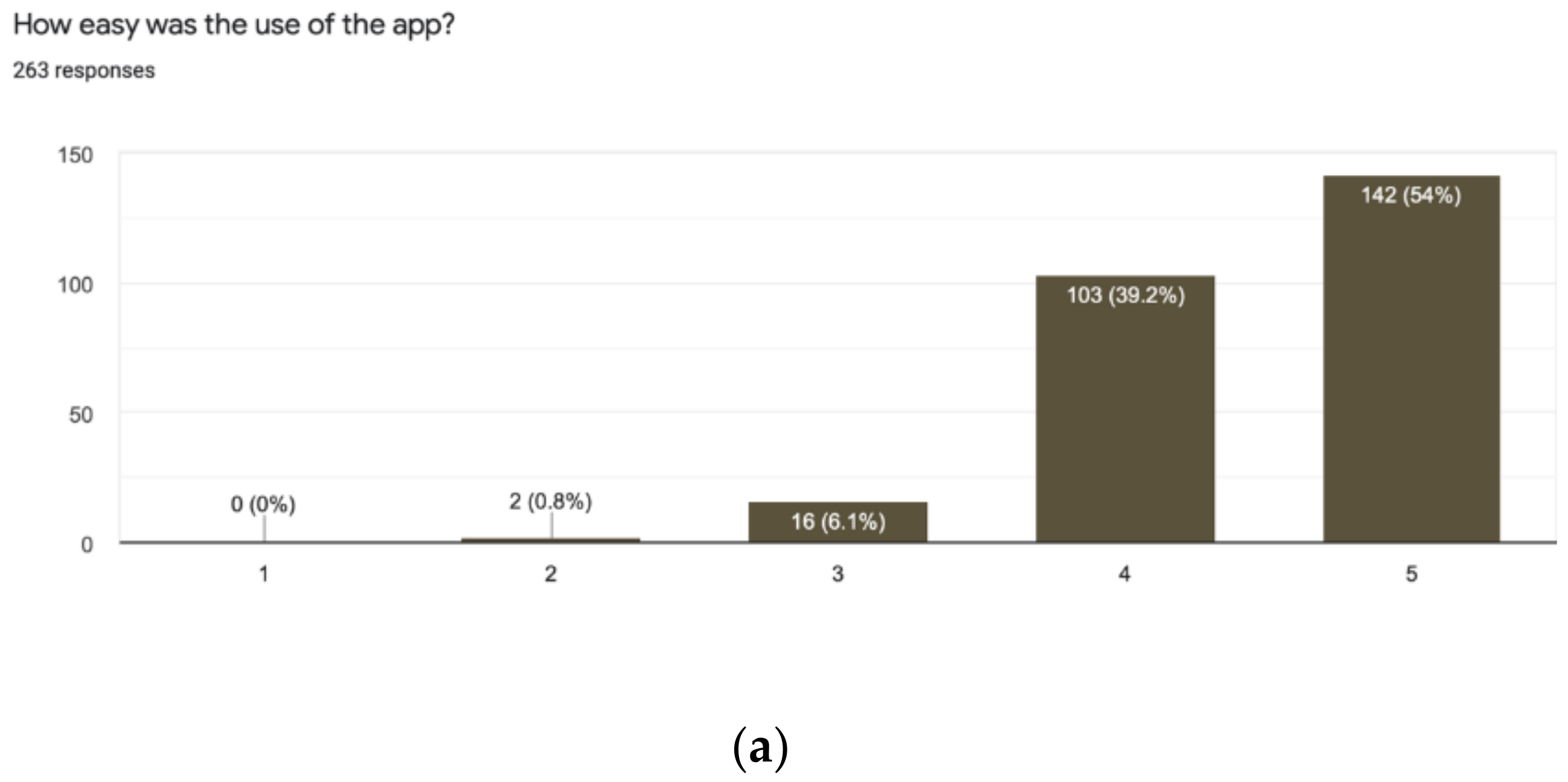

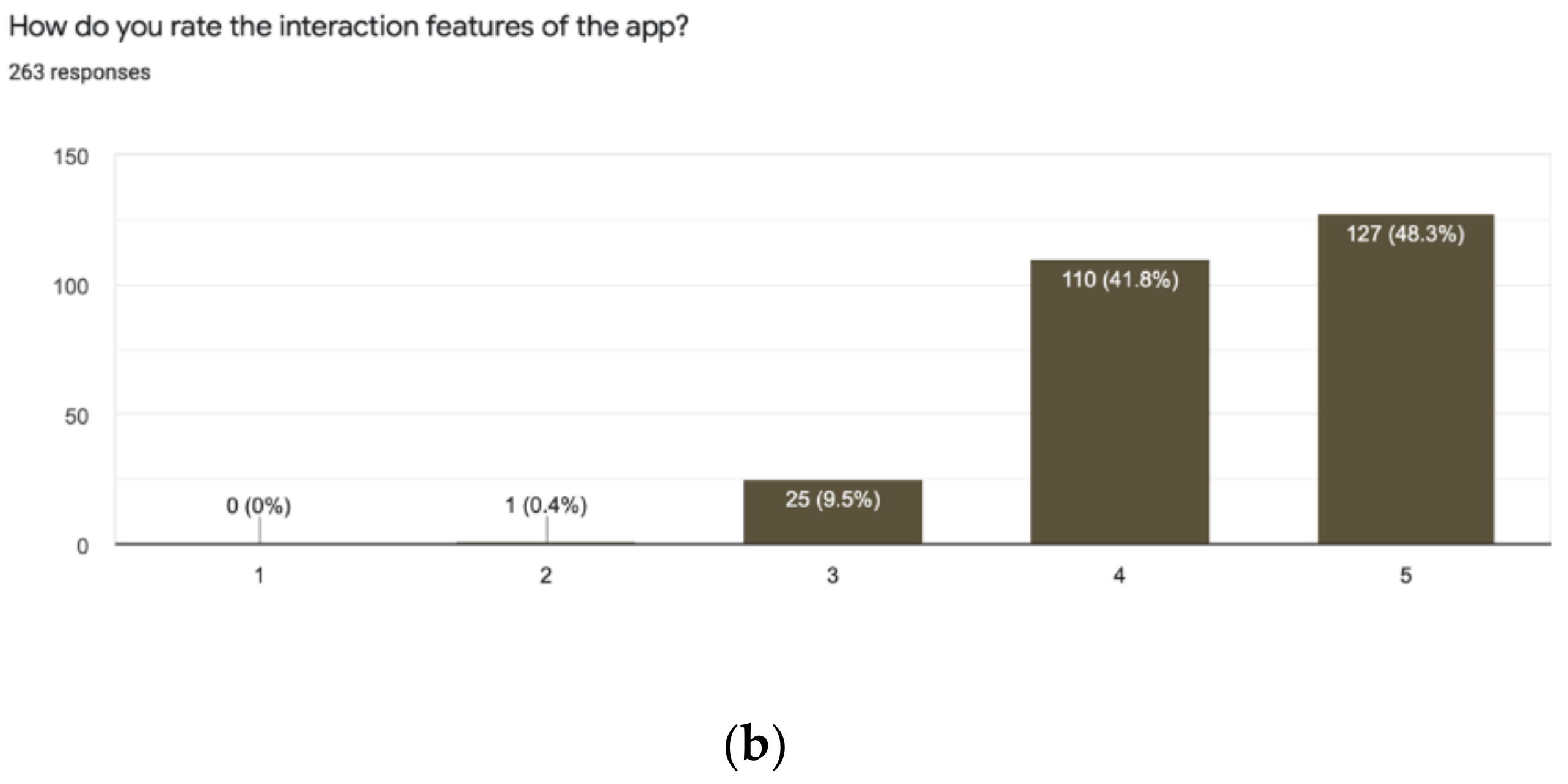

The pilot testing was open to the general audience and was meant as having the end users assessing the usability, game experience, and emotional competence development of the app. Although, at the time, the app had more than 2250 users, it was only possible to collect feedback from 263 that answered an online anonymized questionnaire. Users were spread throughout Europe, with the UK (33.5%), Estonia (20.8%), Romania (17.7%), and Portugal (16.5%) as the leading countries. The average age of the inquired was 23.4 years old, where 65.8% (173) of them were female and 33.5% (88) were male, and 2 people did not specify their gender. In addition, 63% of the people had higher education and 21.8% had completed high school; others had more specific educations such as vocational training.

As can be seen in

Figure 5, the app was highly rated on usability and interaction (a 5-level Likert scale was used with 5 as the most positive), as can be seen in the next two graphs. In addition, 89.3% of the users also mentioned that it had been easy to find all the features of the app.

The contents of the app were also rated very highly, as can be seen in

Figure 6. Most people (77.9%) thought that the app promoted knowledge and understanding of emotions and that the information provided by the app was relevant to most people’s needs (60.3% of the users). Most people (77.6%) agreed that the app contributed to developing emotional intelligence, although 17% were not so sure about this aspect.

Most of the respondents mentioned that they would use the LoEL application again, as can be seen in

Figure 7.

Testers were also asked to provide qualitative feedback about the app, which is summarized as follows:

They were fond of the personalization of the avatar and the originality of the content. The content was considered attractive and fun. It was easy to use, and the design was considered as attractive.

The app provided seamless learning; it felt just like playing without realizing that you were actually learning. They learned many unknown feelings and words. They also realized that, often, we do not understand the feelings of others. Several of the games were presented as the favorites.

There were very few negative comments: one user did not like some of the used pictures, another disliked the music. One complained about the little variety in the first level and that it took a lot of effort to move to the following levels.

Testers also gave recommendations to make the application better: more attractive graphics for teenagers as the design was thought to be more for a younger audience; more games, content, and variety in the games; more customizable options such as a non-binary gender, other clothes, or furniture; a more thorough introduction on what are feelings, emotions, and emoticons; the possibility to connect it to social media; more variety in the music and more agility.

One thorough and helpful comment mentioned that “… instead of right or wrong answers, let them earn points by using the app more doing more exercises there or something. Encourage them to think that everything they feel is right, instead of no that was wrong. I also think that this app could be more interactive. The idea behind of it is great, though”.

4. Conclusions

Emotions provide information about oneself and the others and constitute a feedback system that delivers information that drives behavior and decisions. Emotional intelligence has been acknowledged as a key success factor both in personal and professional life and there is a need to develop the emotional competence of young people so that they are successful in both domains.

The League of Emotions Learners project sought to empower this collective for them to be able to understand, manage, express, and communicate emotions. The LoEL app was created as a tool that young people could relate with that precise objective. Looking at the testing and evaluation results, it is possible to state that the overall outcome of the project was accomplished in a very positive way, and it is also important to note that the positive results were independent (with only minimal differences that may be due to slightly different testing conditions) in relation to gender (4.5 vs. 4.3 average in content rate for male and female participants and 4.5 vs. 4.4 in interaction rate), education level, age (4.36 vs. 4.32 in content rate for younger vs. older students and 4.39 vs. 4.38 in interaction rate), and country (4.1 in Spain vs. 4.6 in Portugal and England in the interaction rate and 4.1 in Spain vs. 4.6 in Italy in the content rate). These results were surely a consequence of the constant and consistent feedback from the end users—young people and youth workers—throughout the project.