Identification and Validation of an Autophagy-Related Gene Signature for Prognostic Prediction and Immunotherapy Response in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. RNA-Seq Expression Data Processing

2.3. scRNA-Seq Data Processing

2.4. Establishment of the Prognostic Model Based on Autophagy-Related Genes

expr (NLRX1) − 0.09516 × expr (MAGEA3),

2.5. Validation of the Candidate Genes and the 4-ARGs Model

2.6. Construction of a Nomogram

2.7. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

2.8. Immune Infiltration Analysis

2.9. Predicting Responses to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs) Using the 4-ARGs Model

2.10. Drug Sensitivity Analysis

2.11. Pan-Cancer Analysis

2.12. Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA)

2.13. Quantitative RT-PCR Validation

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Autophagy-Related Genes with Differential Expression Patterns in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.2. Establishment of the Prognostic Model Based on Autophagy-Related Genes

expr (NLRX1) − 0.09516 × expr (MAGEA3),

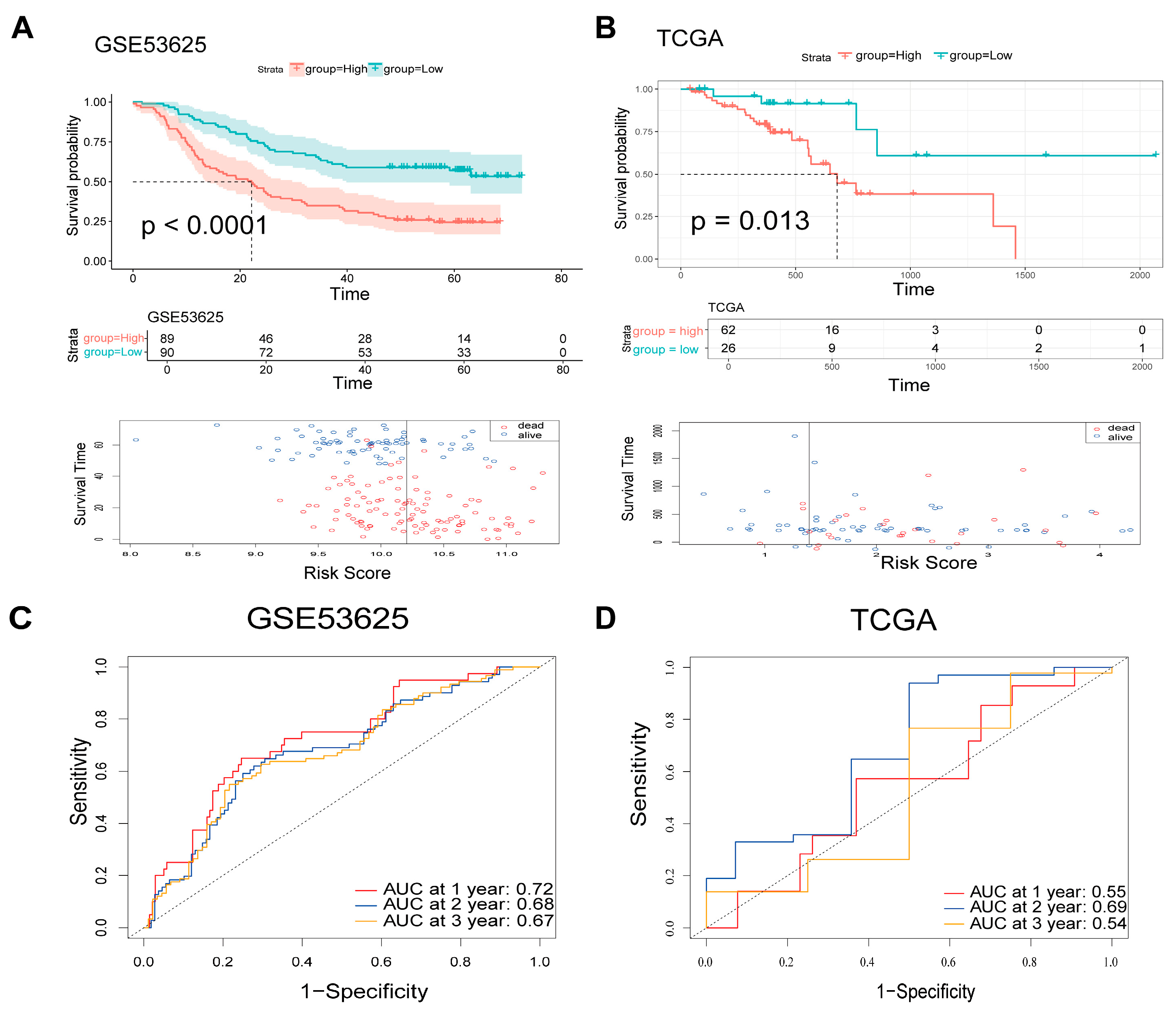

3.3. Validation of the Candidate Genes and the 4-ARGs Model

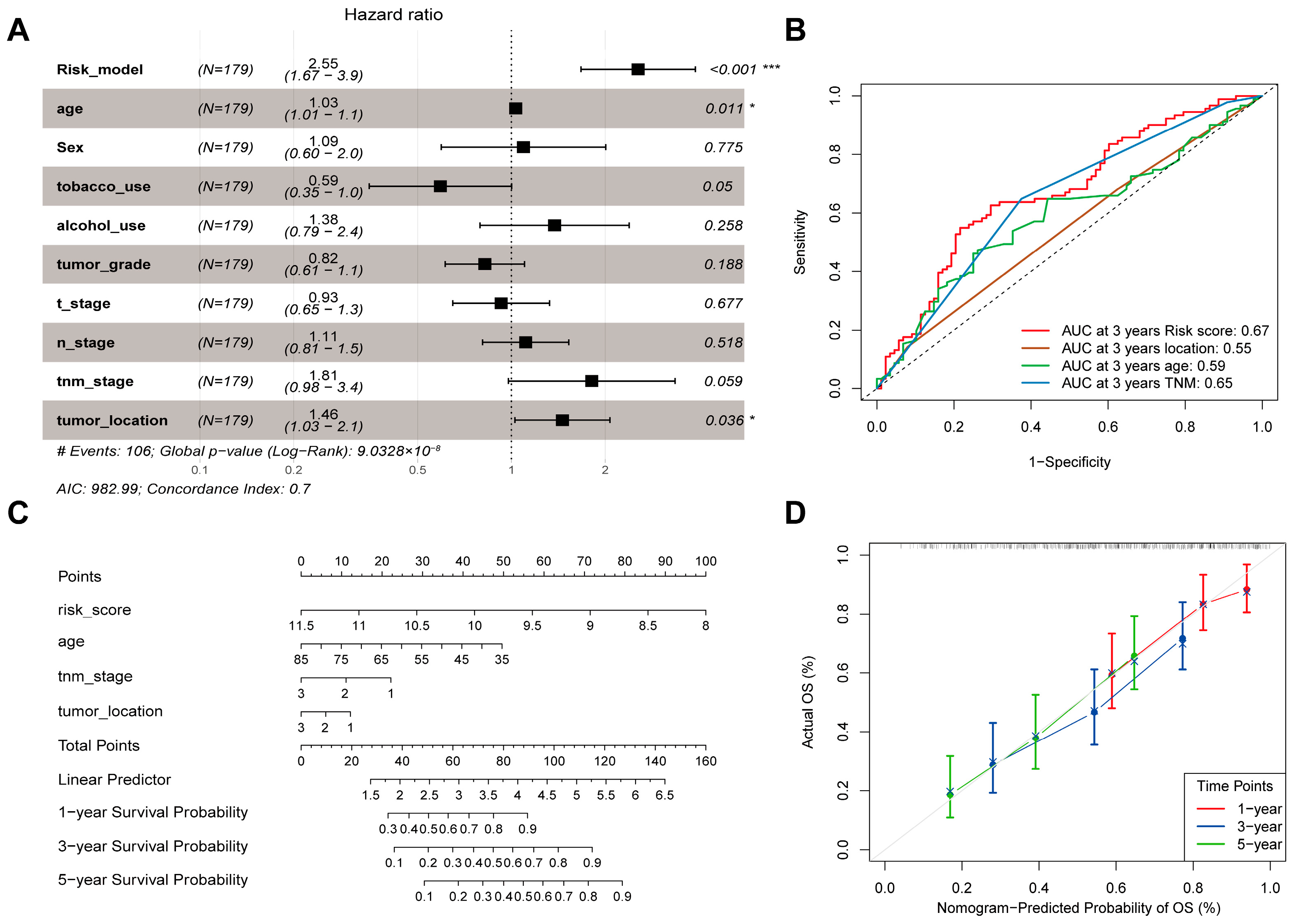

3.4. Identification of Independent Clinical Prognostic Factors and Nomogram Construction

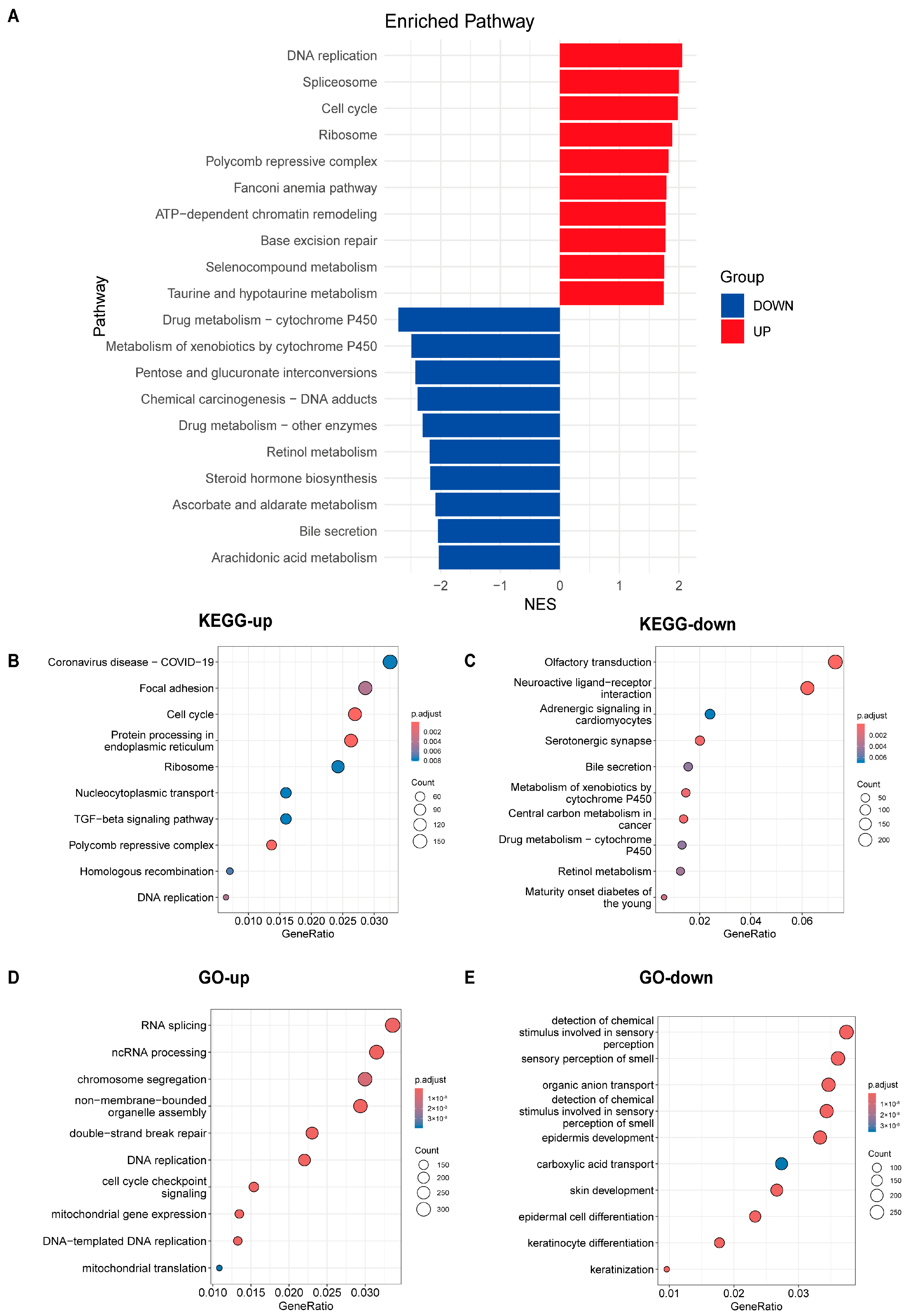

3.5. Analysis of Pathway Differences Between High-Risk and Low-Risk Groups

3.6. Immune Infiltration Analysis and Relationship Between Candidate Genes and Immunity

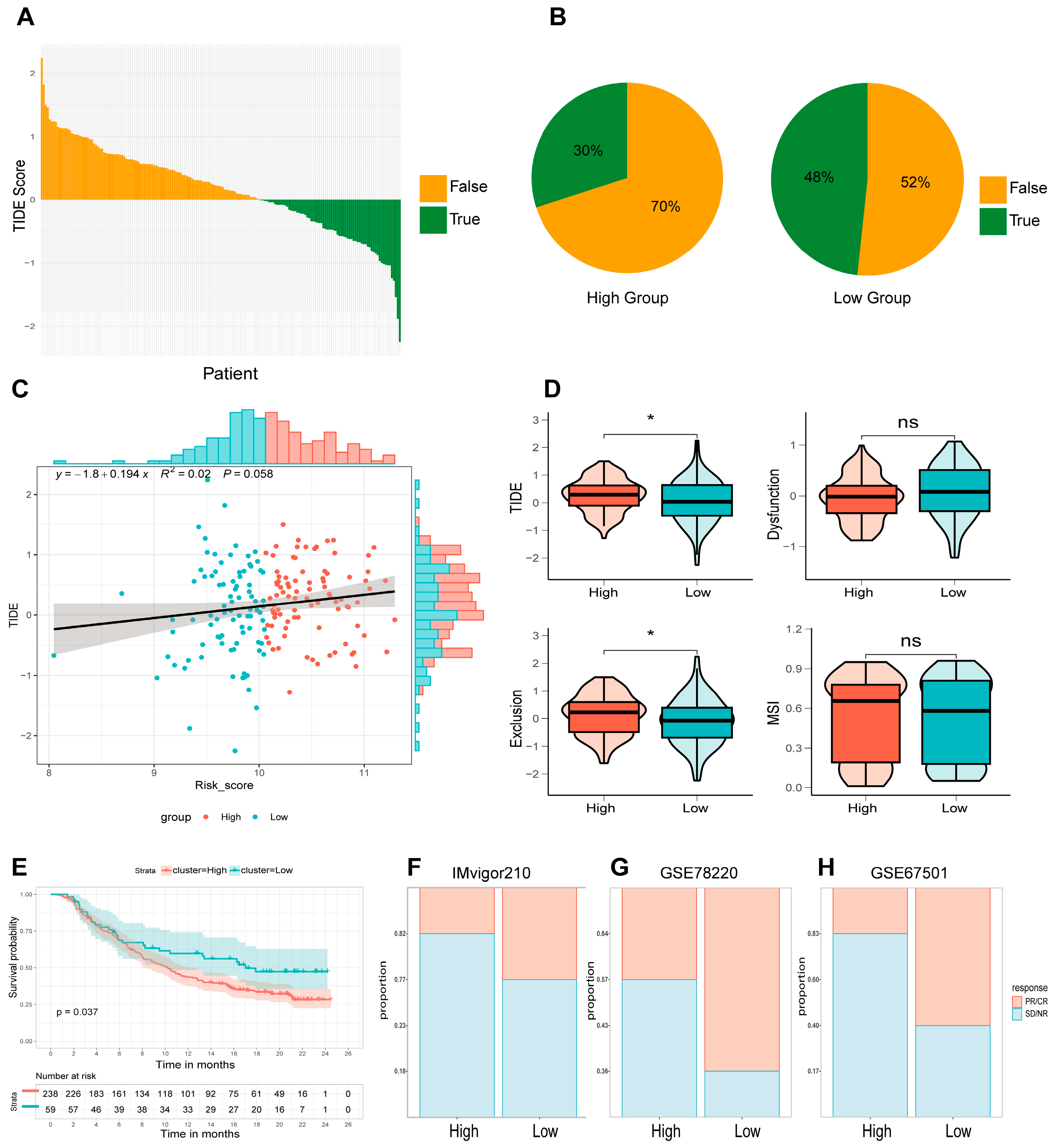

3.7. Immunotherapy Response in High- and Low-Risk Groups Defined by the 4-ARGs Model

3.8. Drugs Sensitivity

3.9. Prognostic Value of the 4-ARGs Model and Candidate Genes in Pan-Cancer

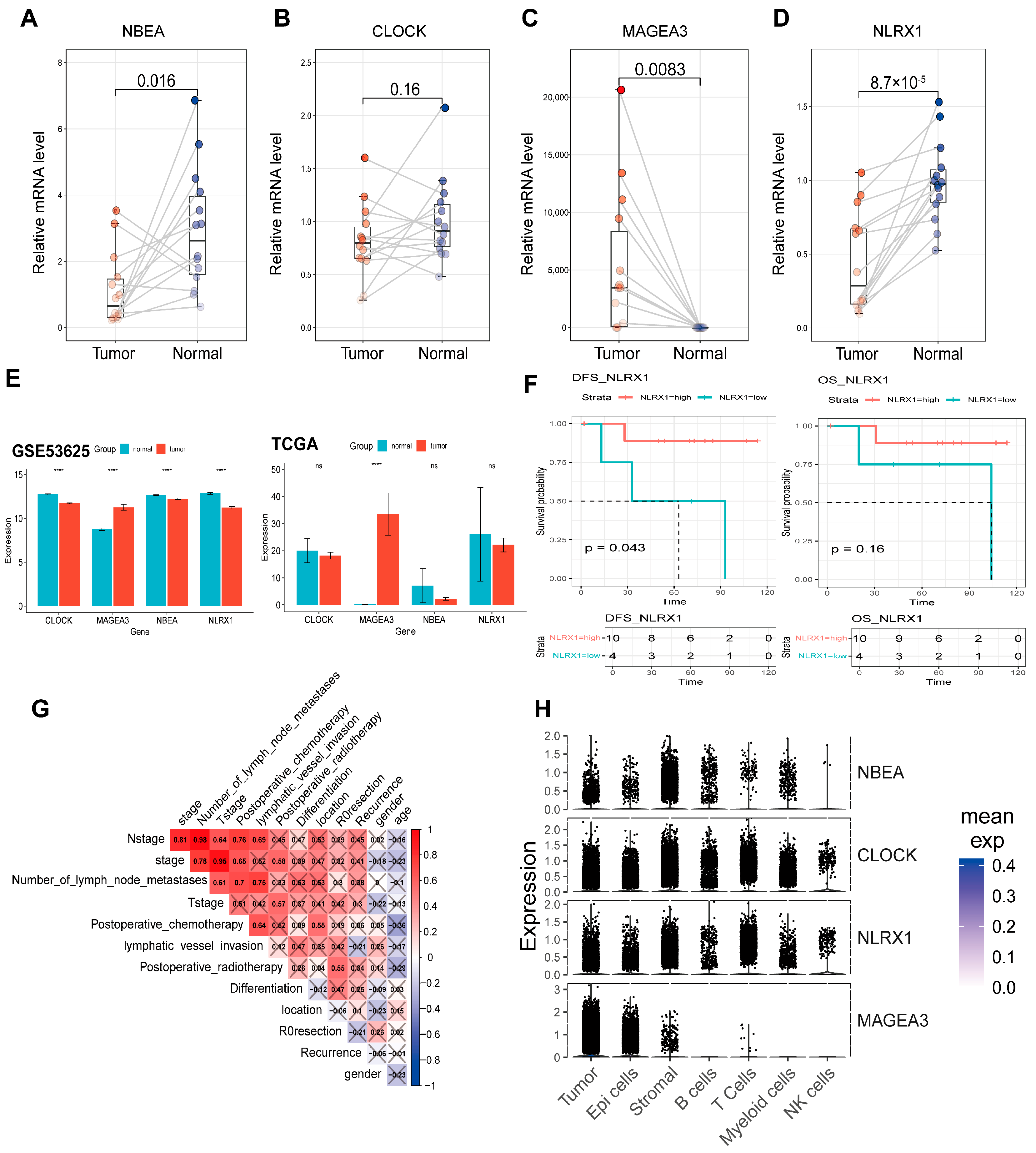

3.10. Validation of Candidate Genes in ESCC Patients and Clinical Data Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESCC | Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| ARG | Autophagy-Related Gene |

| DEG | Differentially Expressed Gene |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| DFS | Disease-Free Survival |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| KM | Kaplan–Meier |

| TIME | Tumor Immune Microenvironment |

| ICI | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor |

| CR | Complete Response |

| PR | Partial Response |

| PD | Progressive Disease |

| SD | Stable Disease |

| IC50 | Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| NAT | Normal Adjacent Tissue |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| NES | Normalized Enrichment Score |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

References

- Pennathur, A.; Gibson, M.K.; Jobe, B.A.; Luketich, J.D. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet 2013, 381, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Zheng, R.; Zeng, H.; Wang, S.; Sun, K.; Chen, R.; Li, L.; Wei, W.; He, J. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 2024, 4, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zheng, R.; Baade, P.D.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, H.; Bray, F.; Jemal, A.; Yu, X.Q.; He, J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, P.K.; Chen, H.S.; Wang, B.Y.; Wu, S.C.; Liu, C.Y.; Shih, C.H.; Liu, C.C. Hospital type- and volume-outcome relationships in esophageal cancer patients receiving non-surgical treatments. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J.M.M.; Towers, C.G.; Thorburn, A. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, L.; Ao, H.; Zhao, M.; Leng, X.; Liu, M.; Ma, J.; Zhu, J. Prognostic implications of autophagy-associated gene signatures in non-small cell lung cancer. Aging 2019, 11, 11440–11462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E. The role for autophagy in cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Pietrocola, F.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Cecconi, F.; Codogno, P.; Debnath, J.; Gewirtz, D.A.; Karantza, V.; et al. Autophagy in malignant transformation and cancer progression. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 856–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.M.; Thorburn, A. Targeting autophagy during cancer therapy to improve clinical outcomes. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 131, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalingam, D.; Mita, M.; Sarantopoulos, J.; Wood, L.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Davis, L.E.; Mita, A.C.; Curiel, T.J.; Espitia, C.M.; Nawrocki, S.T.; et al. Combined autophagy and HDAC inhibition: A phase I safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic analysis of hydroxychloroquine in combination with the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat in patients with advanced solid tumors. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangwala, R.; Leone, R.; Chang, Y.C.; Fecher, L.A.; Schuchter, L.M.; Kramer, A.; Tan, K.S.; Heitjan, D.F.; Rodgers, G.; Gallagher, M.; et al. Phase I trial of hydroxychloroquine with dose-intense temozolomide in patients with advanced solid tumors and melanoma. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogl, D.T.; Stadtmauer, E.A.; Tan, K.S.; Heitjan, D.F.; Davis, L.E.; Pontiggia, L.; Rangwala, R.; Piao, S.; Chang, Y.C.; Scott, E.C.; et al. Combined autophagy and proteasome inhibition: A phase 1 trial of hydroxychloroquine and bortezomib in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1380–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kijima, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Shimonosono, M.; Chandramouleeswaran, P.M.; Hara, T.; Sahu, V.; Kasagi, Y.; Kikuchi, O.; Tanaka, K.; Giroux, V.; et al. Three-Dimensional Organoids Reveal Therapy Resistance of Esophageal and Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 7, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, R.; Klochkova, A.; Murray, M.G.; Kabir, M.F.; Samad, S.; Beccari, T.; Gang, J.; Patel, K.; Hamilton, K.E.; Whelan, K.A. Roles for Autophagy in Esophageal Carcinogenesis: Implications for Improving Patient Outcomes. Cancers 2019, 11, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberzon, A.; Subramanian, A.; Pinchback, R.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Tamayo, P.; Mesirov, J.P. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1739–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.N.; Dong, J.; Zhang, L.; Ouyang, D.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, A.F.; Lu, A.P.; Cao, D.S. HAMdb: A database of human autophagy modulators with specific pathway and disease information. J. Cheminform. 2018, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Huang, Y.; Kang, J.; Li, K.; Bi, X.; Zhang, T.; Jin, N.; Hu, Y.; Tan, P.; Zhang, L.; et al. ncRDeathDB: A comprehensive bioinformatics resource for deciphering network organization of the ncRNA-mediated cell death system. Autophagy 2015, 11, 1917–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, K.; Suzuki, K.; Sugawara, H. The Autophagy Database: An all-inclusive information resource on autophagy that provides nourishment for research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D986–D990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Tian, L.; Zhou, C.; He, M.Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, F.; Shi, S.; Feng, X.; et al. LncRNA profile study reveals a three-lncRNA signature associated with the survival of patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gut 2014, 63, 1700–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, L.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Pu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guo, W.; Yao, J.; Shao, M.; Fan, W.; et al. Dissecting esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma ecosystem by single-cell transcriptomic analysis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo, W.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Sun, L.; Song, C.; Moreno, B.H.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Berent-Maoz, B.; Pang, J.; Chmielowski, B.; Cherry, G.; et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Features of Response to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma. Cell 2016, 165, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascierto, M.L.; McMiller, T.L.; Berger, A.E.; Danilova, L.; Anders, R.A.; Netto, G.J.; Xu, H.; Pritchard, T.S.; Fan, J.; Cheadle, C.; et al. The Intratumoral Balance between Metabolic and Immunologic Gene Expression Is Associated with Anti-PD-1 Response in Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016, 4, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Necchi, A.; Joseph, R.W.; Loriot, Y.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Petrylak, D.P.; Derleth, C.L.; Tayama, D.; Zhu, Q.; Ding, B.; et al. Atezolizumab in platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma: Post-progression outcomes from the phase II IMvigor210 study. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 3044–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, T.; Butler, A.; Hoffman, P.; Hafemeister, C.; Papalexi, E.; Mauck, W.M., 3rd; Hao, Y.; Stoeckius, M.; Smibert, P.; Satija, R. Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell 2019, 177, 1888–1902.e1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, C.S.; Murrow, L.M.; Gartner, Z.J. DoubletFinder: Doublet Detection in Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data Using Artificial Nearest Neighbors. Cell Syst. 2019, 8, 329–337.e324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, I.; Millard, N.; Fan, J.; Slowikowski, K.; Zhang, F.; Wei, K.; Baglaenko, Y.; Brenner, M.; Loh, P.R.; Raychaudhuri, S. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grambsch, P.M.; Therneau, T.M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, F. Modern Applied Statistics with S. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D Stat. 2003, 52, 704–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Kosinski, M.; Biecek, P. _survminer: Drawing Survival Curves Using ’ggplot2’_. R Package Version 0.5.0. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survminer (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Blanche, P.; Dartigues, J.F.; Jacqmin-Gadda, H. Estimating and comparing time-dependent areas under receiver operating characteristic curves for censored event times with competing risks. Stat. Med. 2013, 32, 5381–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F.E., Jr. _rms: Regression Modeling Strategies_. R Package Version 7.0-0. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rms (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enrichplot: Visualization of Functional Enrichment Result. 2024. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/enrichplot (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Yoshihara, K.; Shahmoradgoli, M.; Martínez, E.; Vegesna, R.; Kim, H.; Torres-Garcia, W.; Treviño, V.; Shen, H.; Laird, P.W.; Levine, D.A.; et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, C.B.; Liu, C.L.; Alizadeh, A.A.; Newman, A.M. Profiling Cell Type Abundance and Expression in Bulk Tissues with CIBERSORTx. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2117, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becht, E.; Giraldo, N.A.; Lacroix, L.; Buttard, B.; Elarouci, N.; Petitprez, F.; Selves, J.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Fridman, W.H.; et al. Estimating the population abundance of tissue-infiltrating immune and stromal cell populations using gene expression. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P.; Gu, S.; Pan, D.; Fu, J.; Sahu, A.; Hu, X.; Li, Z.; Traugh, N.; Bu, X.; Li, B.; et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1550–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J. The Connectivity Map: A new tool for biomedical research. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J.; Crawford, E.D.; Peck, D.; Modell, J.W.; Blat, I.C.; Wrobel, M.J.; Lerner, J.; Brunet, J.P.; Subramanian, A.; Ross, K.N.; et al. The Connectivity Map: Using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science 2006, 313, 1929–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Soares, J.; Greninger, P.; Edelman, E.J.; Lightfoot, H.; Forbes, S.; Bindal, N.; Beare, D.; Smith, J.A.; Thompson, I.R.; et al. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): A resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D955–D961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeser, D.; Gruener, R.F.; Huang, R.S. oncoPredict: An R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbab260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Wang, X. TCGAplot: An R package for integrative pan-cancer analysis and visualization of TCGA multi-omics data. BMC Bioinform. 2023, 24, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hänzelmann, S.; Castelo, R.; Guinney, J. GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatakrishnan, K.; Von Moltke, L.L.; Greenblatt, D.J. Human drug metabolism and the cytochromes P450: Application and relevance of in vitro models. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001, 41, 1149–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadyen, M.C.; Melvin, W.T.; Murray, G.I. Cytochrome P450 enzymes: Novel options for cancer therapeutics. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2004, 3, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Antona, C.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Cytochrome P450 pharmacogenetics and cancer. Oncogene 2006, 25, 1679–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Yang, X.; Shi, Q. The cytochrome P450 inhibitor SKF-525A disrupts autophagy in primary rat hepatocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016, 255, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Wu, Q.; Luan, S.; Yin, Z.; He, C.; Yin, L.; Zou, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Li, L.; Song, X.; et al. A comprehensive review of topoisomerase inhibitors as anticancer agents in the past decade. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 171, 129–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Hei, R.; Li, X.; Cai, H.; Wu, X.; Zheng, Q.; Cai, C. CDK inhibitors in cancer therapy, an overview of recent development. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 1913–1935. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Yang, Q.; Wan, L.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Niu, M.; Liu, H.; et al. Increased Drp1 promotes autophagy and ESCC progression by mtDNA stress mediated cGAS-STING pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Chen, H.; Yang, X.; Han, J.; Yao, X.; Wei, X.; Si, J.; Yao, H.; Liu, H.; et al. TFAM downregulation promotes autophagy and ESCC survival through mtDNA stress-mediated STING pathway. Oncogene 2022, 41, 3735–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhao, M.; Chu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, K.; Zhao, Z.; Feng, A.; Leng, Z.; et al. TAOK3 Facilitates Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Progression and Cisplatin Resistance Through Augmenting Autophagy Mediated by IRGM. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 2023, 10, e2300864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Cheng, B.; Chen, P.; Sun, X.; Wen, Z.; Cheng, Y. BTN3A1 promotes tumor progression and radiation resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by regulating ULK1-mediated autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Venida, A.; Yano, J.; Biancur, D.E.; Kakiuchi, M.; Gupta, S.; Sohn, A.S.W.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Lin, E.Y.; Parker, S.J.; et al. Autophagy promotes immune evasion of pancreatic cancer by degrading MHC-I. Nature 2020, 581, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Thennavan, A.; Dolgalev, I.; Chen, T.; Li, J.; Marzio, A.; Poirier, J.T.; Peng, D.H.; Bulatovic, M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; et al. ULK1 inhibition overcomes compromised antigen presentation and restores antitumor immunity in LKB1 mutant lung cancer. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Wei, S.; Gan, B.; Peng, X.; Zou, W.; Guan, J.L. Suppression of autophagy by FIP200 deletion inhibits mammary tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 1510–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Wang, W.; Crespo, J.; Kryczek, I.; Li, W.; Wei, S.; Bian, Z.; Maj, T.; He, M.; Liu, R.J.; et al. Suppression of FIP200 and autophagy by tumor-derived lactate promotes naïve T cell apoptosis and affects tumor immunity. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2, eaan4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich-Nikitin, I.; Kirshenbaum, E.; Kirshenbaum, L.A. Autophagy, Clock Genes, and Cardiovascular Disease. Can. J. Cardiol. 2023, 39, 1772–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich-Nikitin, I.; Rasouli, M.; Reitz, C.J.; Posen, I.; Margulets, V.; Dhingra, R.; Khatua, T.N.; Thliveris, J.A.; Martino, T.A.; Kirshenbaum, L.A. Mitochondrial autophagy and cell survival is regulated by the circadian Clock gene in cardiac myocytes during ischemic stress. Autophagy 2021, 17, 3794–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, R.; Kodali, K.; Peng, J.; Potts, P.R. Regulation of MAGE-A3/6 by the CRL4-DCAF12 ubiquitin ligase and nutrient availability. EMBO Rep 2019, 20, e47352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Wen, H.; Yu, Y.; Taxman, D.J.; Zhang, L.; Widman, D.G.; Swanson, K.V.; Wen, K.W.; Damania, B.; Moore, C.B.; et al. The mitochondrial proteins NLRX1 and TUFM form a complex that regulates type I interferon and autophagy. Immunity 2012, 36, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Yang, Q.; Cao, Z.; Li, H.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Sun, G.; Man, R.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Activation of NLRX1-mediated autophagy accelerates the ototoxic potential of cisplatin in auditory cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018, 343, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Liu, K.; Cheng, D.; Zheng, B.; Li, S.; Mo, Z. The regulatory role of NLRX1 in innate immunity and human disease. Cytokine 2022, 160, 156055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Gan, L.; Sun, C.; Chu, A.; Yang, M.; Liu, Z. Bioinformatics analysis and experimental verification of NLRX1 as a prognostic factor for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2024, 27, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, B.; Senapati, S. Immunological and functional aspects of MAGEA3 cancer/testis antigen. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2021, 125, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Ge, X.; Gao, Z.; Shi, Y.; Yang, M. MAGEA3 serves as an independent indicator for predicting the prognosis of ESCC. Panminerva Med. 2021, 63, 382–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yang, P.; Wei, H.; Mai, P.; Yu, X. Development of a prognostic nomogram based on an eight-gene signature for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA). Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Chen, H.; Xia, J.; Li, T.; Ye, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, K.; Shi, J.; et al. Diagnostic performance of anti-MAGEA family protein autoantibodies in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 125, 111041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Fang, B.; Ping, Y.; Qin, G.; Yue, D.; Li, F.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y. Decitabine enhances tumor recognition by T cells through upregulating the MAGE-A3 expression in esophageal carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.Y.; Wang, Y.G.; Ma, S.J.; Yang, B.Y.; Li, Q.P. Identification of a prognostic 5-Gene expression signature for gastric cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 143, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipunova, N.; Wesselius, A.; Cheng, K.K.; van Schooten, F.J.; Bryan, R.T.; Cazier, J.B.; Galesloot, T.E.; Kiemeney, L.; Zeegers, M.P. Genome-wide Association Study for Tumour Stage, Grade, Size, and Age at Diagnosis of Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2019, 2, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Kasperbauer, J.L.; Tombers, N.M.; Cornell, M.D.; Smith, D.I. Prognostic significance of decreased expression of six large common fragile site genes in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Transl. Oncol. 2014, 7, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, W.; Hsu, W.H.; Khan, F.; Dunterman, M.; Pang, L.; Wainwright, D.A.; Ahmed, A.U.; Heimberger, A.B.; Lesniak, M.S.; Chen, P. Circadian Regulator CLOCK Drives Immunosuppression in Glioblastoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2022, 10, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Wang, Z.; Ye, L.; Duan, Y.; Jiang, H.; He, H.; Xiao, L.; Wu, Q.; Xia, Y.; Yang, M.; et al. Nucleus-exported CLOCK acetylates PRPS to promote de novo nucleotide synthesis and liver tumour growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2023, 25, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutilier, A.J.; Elsawa, S.F. Macrophage Polarization States in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, C.C.; Malanchi, I. Neutrophils in cancer: Heterogeneous and multifaceted. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speiser, D.E.; Chijioke, O.; Schaeuble, K.; Münz, C. CD4(+) T cells in cancer. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Weng, Y.; Ding, N.; Cheng, C.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, W. Autophagy-Related Three-Gene Prognostic Signature for Predicting Survival in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 650891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Li, L.; Lin, H.; Yu, Y. A fibroblast-associated signature predicts prognosis and immunotherapy in esophageal squamous cell cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1199040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Sun, Y.; Wei, W.; Huang, Z.; Cheng, M.; Qiu, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Q.; et al. RNA modification-related genes illuminate prognostic signature and mechanism in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. iScience 2024, 27, 109327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Li, M.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, Z.; Liang, J.; Bi, G.; Bian, Y.; Sui, Q.; Zhan, C.; Lin, M.; et al. Identification and analysis of a prognostic ferroptosis and iron-metabolism signature for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Cancer 2022, 13, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, R.; Wang, X.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Fu, F.; Zhou, H. Identification and Validation of an Autophagy-Related Gene Signature for Prognostic Prediction and Immunotherapy Response in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2026, 18, 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030388

Chen R, Wang X, Li G, Zhang H, Fu F, Zhou H. Identification and Validation of an Autophagy-Related Gene Signature for Prognostic Prediction and Immunotherapy Response in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers. 2026; 18(3):388. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030388

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Rui, Xinran Wang, Guanyang Li, Hao Zhang, Fangqiu Fu, and Hanlin Zhou. 2026. "Identification and Validation of an Autophagy-Related Gene Signature for Prognostic Prediction and Immunotherapy Response in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma" Cancers 18, no. 3: 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030388

APA StyleChen, R., Wang, X., Li, G., Zhang, H., Fu, F., & Zhou, H. (2026). Identification and Validation of an Autophagy-Related Gene Signature for Prognostic Prediction and Immunotherapy Response in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers, 18(3), 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030388