Ex Vivo Organotypic Brain Slice Models for Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Model Variant | Tissue Source | Main Experimental Application | Main Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodent-derived organotypic brain slices | Mouse or rat brain (postnatal or adult) | Mechanistic studies of tumour invasion and migration | High reproducibility, wide availability, good imaging accessibility, standardised protocols | Species mismatch, limited human immune and stromal relevance |

| Human patient-derived tumour slices | Surgical GBM tissue | Patient-specific invasion profiling and therapeutic response assessment | Preservation of native human cytoarchitecture and tumour heterogeneity | Limited availability, inter-patient variability, lower scalability |

| Human nontumoural brain slices with GBM cell implantation | Human cortical tissue (e.g., epilepsy surgery) | Controlled tumour–host interaction and invasion modelling | Human extracellular matrix and vasculature preserved, controlled tumour seeding | Lacks native tumour architecture and endogenous tumour microenvironment |

| Xenograft-derived organotypic slices | Orthotopic human GBM xenografts in rodents | Bridging in vivo and ex vivo tumour behaviour | Maintains tumour structure and perfusion-related features | Mixed-species environment, altered immune context |

| Hybrid/engineered organotypic systems (e.g., tandem cultures, slice-on-a-chip) | Human and/or rodent slices with microengineering | Drug screening, perfusion-controlled assays, precision oncology applications | Improved control of nutrient/drug delivery, extended viability, multiplex testing | Technical complexity, lower throughput, limited standardisation |

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Model: preclinical experimental studies investigating ex vivo organotypic brain slice cultures.

- Focus: investigation of GBM biology, including tumour invasion and cell migration, tumour–microenvironment interactions and therapeutic response to treatment;

- Study type: peer-reviewed original research articles.

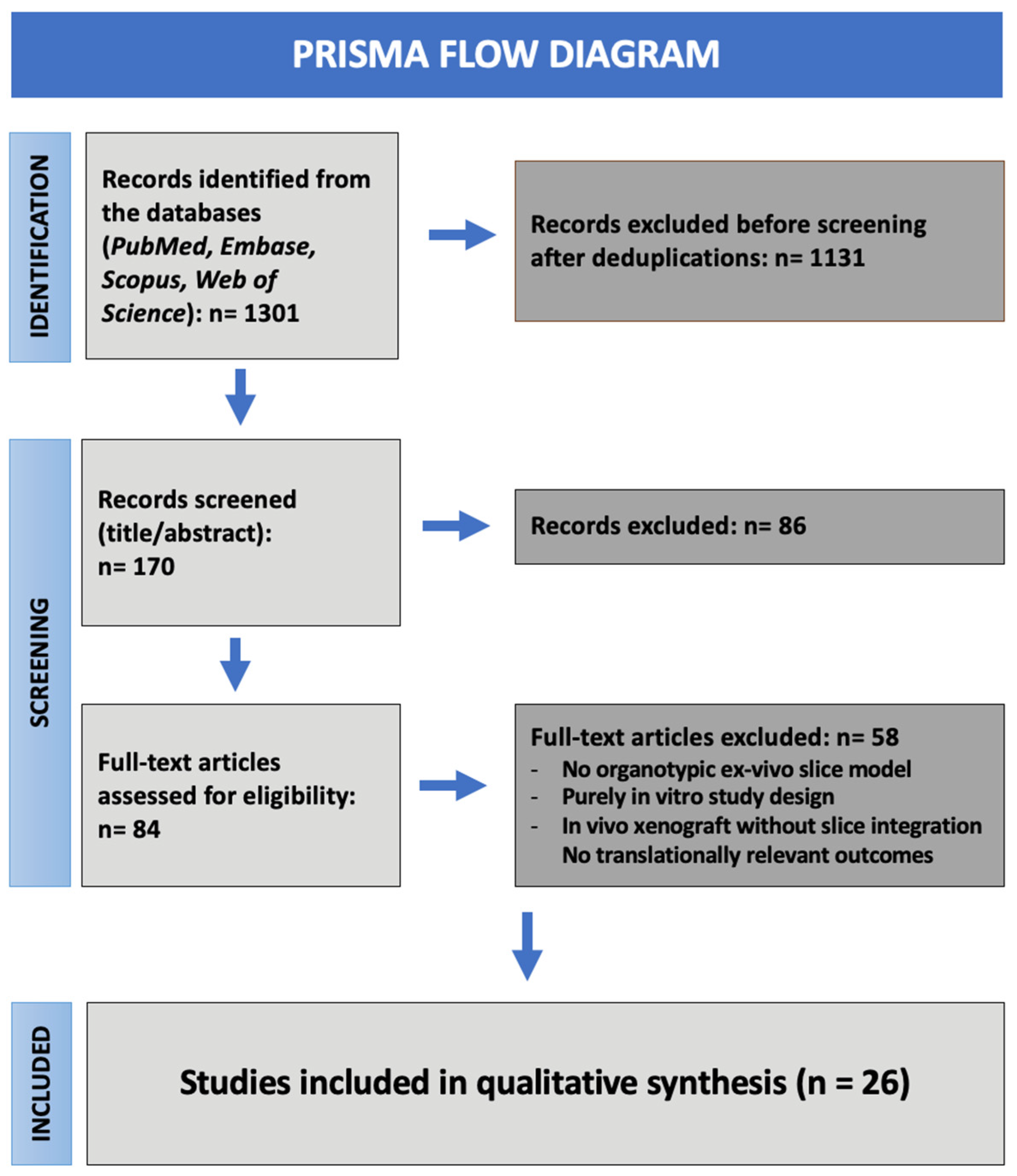

2.3. Screening and Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2.1. Model Types and Slice Source

- Rodent-derived slices: Fourteen studies (54%). These slices were typically obtained from postnatal day 3–14 mouse or rat brains and represented the most commonly used tissue platform. These models used rodent brain slices as a scaffold for human glioma cells (predominantly GBM-derived) or GBM stem cells (GSCs) [20,26];

- Hybrid or engineered platforms: Two studies (8%). These studies applied more complex configurations combining different tissue sources or microengineering. This group includes the tandem slice system from Sidorcenco et al. [28] and the platform designed by Mann et al. using human GBM tissue perfused on rodent host slices [25].

3.2.2. Slice Thickness and Culture Duration

- Thick slices (≥350–400 µm) are employed when preserving vascular niches or white-matter organisation is required [31].

3.3. Methodological Heterogeneity

3.3.1. Slice Origin Variability

3.3.2. Functional Impact of Thickness Choices

3.3.3. Tumour Introduction Strategies

- Microinjection of dissociated tumour cells (45%)

- 2.

- Spheroid placement on slice surface (30%)

- 3.

- Native tumour tissue without implantation (25%)

3.3.4. Culture Media, Oxygenation and Environmental Conditions

- Low-serum or serum-containing media were used for short-term assays [27];

3.3.5. Outcome Measures and Quantification Workflows

3.3.6. Reporting Quality and Sources of Bias

- Limited reporting of viability controls (only ~20% of studies used systematic live/dead or LDH assays);

- Inconsistent documentation of oxygenation and perfusion parameters;

- Blinding and randomisation;

- Sample-size justification absent in nearly all studies;

- Media composition often reported incompletely.

3.4. Applications of Organotypic Brain Slice Models in Glioblastoma Research

3.4.1. Tumour Invasion and Migration

- Gritsenko et al. identified peculiar perivascular and astrocyte-guided invasion preferred paths [26];

- Eisemann et al. instead perfectioned a model to quantify invasion distance [33];

- Decotret et al., in his paper, described an optimised 3D invasion assay (BraInZ) distinguishing invasion modalities [29];

- Linder et al. described how a solution with arsenic trioxide (ATO) together with gossypol could suppress GSC invasion [18].

- Ravi et al. instead showed structural determinants of invasion microinjecting patient-derived cells [22];

- Liu et al. quantified how TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis modifies residual invasive fronts [27];

- Merz et al. showed variable invasion depth and proliferation within the same GBM tissue [19].

- Slice thickness and oxygen tension have been reported as extremely relevant in terms of invasion patterns [22].

3.4.2. Tumour–Microenvironment Interactions

- Heiland et al. described that GBM cells can drive reactive astrocytes to adopt immunosuppressive states driven by microglia–tumour signalling [39];

- Ghoochani et al. documented tumour-induced angiogenesis and microglial activation in its Vascular Organotypic Glioma Impact Model (VOGIM) model [31];

- Raju et al. in 2015 demonstrated long-term maintenance of microglia and endothelial cells in human GBM slices allowing more in depth TME analysis [34].

- Anderson and its group in 2024 designed a model of an ex vivo slice environment with integration of T-cell infiltration and migration describing interactions in real time [35].

- Ravin et al. demonstrated how primary GBM cells preferentially migrate following blood vessels and very interestingly how oxygen concentration dynamically modulate their speed and migration patterns [41];

- Nickl et al. reported that patient-derived slices retain native stromal, vascular, and immune system providing a physiological environment for modelling therapeutic responses [24].

- Preservation of astrocytes, microglia, vasculature and ECM has been found essential for reproducing relevant GBM behaviour;

- Patient-derived slices uniquely retain immune and stromal components which are basically absent in organoids, spheroids or in 2D systems;

- Ex vivo TME dynamics often replicate in vivo patterns such as perivascular invasion and angiogenic remodelling.

3.4.3. Therapeutic Testing

- Merz et al. described a model assessing patient-specific responses to temozolomide, X-rays and carbon ions [19];

- Minami and his team applied cisplatin, paclitaxel and tranilast showing distinct efficacy and toxicity profiles [20];

- Maier et al. reported instead how mGluR3 inhibition sensitises GBM cells to alkylating agents [38];

- Linder et al. applied on their model a mix of arsenic trioxide and gossypol reporting a synergistic killing of GSCs coupled to regrowth suppression [18];

- Nickl et al. showed how patient-derived GBM slices have heterogeneous responses to temozolomide, lomustine and targeted compounds [24];

- Xu et al. added to their slices the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat inducing histone hyperacetylation and anti-proliferative effects in human glioma slices [23].

- Ravi et al. used human cortical organotypic slices to test environmental and pharmacological perturbations, demonstrating preserved microenvironmental architecture suitable for assessing GBM cell responses [22];

- Mann et al. described a patient-tailored drug screening using a mixed-species engineered organotypic system [25].

- Liu et al. delivered soluble TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) induced dose-dependent apoptosis and reduced tumour mass in human glioma slices [27].

3.5. Summary of Findings

- Preservation of human cytoarchitecture, vasculature, ECM, and stromal populations allows modelling of tumour behaviour in a closer to physiology context;

- Faithful reproduction of GBM invasion patterns, notably perivascular, white-matter and astrocytic boundary modulated migration, documented both through rodent and human models;

- Robust TME-related insights, particularly microglia–tumour communication, were strongly and repeatedly confirmed across all types of models;

- Ability to evaluate drug responses in patient-specific environments, supporting potential future applications in functional precision oncology.

- Substantial high methodological heterogeneity, including differences in slice thickness, media composition, oxygenation, tumour implantation methods and culture duration;

- Incomplete reporting across the majority of the studies regarding metrics viability, oxygen control, experimental blinding, and sample-size justification, therefore significantly reducing comparability across studies;

- High variability in perfusion and drug delivery conditions, especially between static cultures and engineered platforms affecting drug penetration and effect sizes;

- Species differences, particularly between rodent and human slices, affecting immune cell retention, vascular integrity and invasion phenotypes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Invasion Biology

4.2. Therapeutic Testing and Translational Potential

4.3. Methodological Variability and Challenges

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATO | arsenic trioxide; |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; |

| ECM | extracellular matrix; |

| GBM | glioblastoma; |

| GSC | glioma stem cell; |

| HDAC | histone deacetylase; |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase; |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; |

| ROBINS-I | Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies; |

| SYRCLE | Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory animal Experimentation; |

| TME | tumour microenvironment; |

| TNF | tumour necrosis factor; |

| TRAIL | tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; |

| TTFields | tumour-treating fields; |

| TUNEL | terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labelling; |

| VOGIM | Versatile Organotypic Glioma Invasion Model. |

Appendix A

| Parameter | Optimal Range/Condition | Suboptimal Condition | Impact on Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slice thickness | 250–350 µm | <200 µm or >400 µm | Excessively thin slices compromise cytoarchitecture, while overly thick slices develop hypoxia and reduced viability, affecting invasion and drug–response readouts |

| Tissue source | Patient-derived GBM tissue | Long-term established cell lines only | Reduced tumour heterogeneity and loss of patient-specific invasion and treatment response patterns |

| Culture duration | Short- to mid-term (3–14 days) | Prolonged culture without optimisation | Progressive loss of tissue viability and altered microenvironmental signalling |

| Oxygenation strategy | Interface culture or controlled perfusion | Static submerged culture | Impaired oxygen diffusion, central necrosis, and altered invasion dynamics |

| Culture medium | Serum-free, neurobasal-based formulations | Serum-containing media | Artificial differentiation and non-physiological tumour behaviour |

| Tumour implantation strategy | Native tumour slices or controlled microinjection | Irregular or poorly controlled seeding | Reduced reproducibility and increased variability of invasion assays |

| Functional readouts | Multimodal assessment (imaging, viability, molecular markers) | Single endpoint analysis only | Incomplete or misleading interpretation of tumour behaviour and therapeutic response |

References

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Gittleman, H.; Truitt, G.; Boscia, A.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro-Oncology 2018, 20, Iv1–Iv86, Erratum in Neuro-Oncology 2018, 23, 508–522. https://doi.org/10.1093/Neuonc/Noy171. PMID: 30445539; PMCID: PMC6129949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Hegi, M.E.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Janzer, R.C.; Ludwin, S.K.; Allgeier, A.; Fisher, B.; Belanger, K.; et al. Effects of Radiotherapy with Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide versus Radiotherapy Alone on Survival in Glioblastoma in a Randomised Phase III Study: 5-Year Analysis of the EORTC-NCIC Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Du, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Gu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, A.; Gao, S.; Shao, A.; Zhang, J.; et al. Tumor Treating Fields in Glioblastoma: Long-Term Treatment and High Compliance as Favorable Prognostic Factors. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1345190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Salgado, M.A.; Villamayor, M.; Albarrán, V.; Alía, V.; Sotoca, P.; Chamorro, J.; Rosero, D.; Barrill, A.M.; Martín, M.; Fernandez, E.; et al. Recurrent Glioblastoma: A Review of the Treatment Options. Cancers 2023, 15, 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sottoriva, A.; Spiteri, I.; Piccirillo, S.G.M.; Touloumis, A.; Collins, V.P.; Marioni, J.C.; Curtis, C.; Watts, C.; Tavaré, S. Intratumor Heterogeneity in Human Glioblastoma Reflects Cancer Evolutionary Dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4009–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amico, A.G.; Maugeri, G.; Vanella, L.; Pittalà, V.; Reglodi, D.; D’Agata, V. Multimodal Role of PACAP in Glioblastoma. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, A.G.; Maugeri, G.; Magrì, B.; Giunta, S.; Saccone, S.; Federico, C.; Pricoco, E.; Broggi, G.; Caltabiano, R.; Musumeci, G.; et al. Modulatory Activity of ADNP on the Hypoxia-induced Angiogenic Process in Glioblastoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2023, 62, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, G.; D’Amico, A.G.; Saccone, S.; Federico, C.; Rasà, D.M.; Caltabiano, R.; Broggi, G.; Giunta, S.; Musumeci, G.; D’Agata, V. Effect of PACAP on Hypoxia-Induced Angiogenesis and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Glioblastoma. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, A.G.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Virtuoso, A. Identification of Molecular Targets and Anti-Cancer Agents in GBM: New Perspectives for Cancer Therapy. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtuoso, A.; D’Amico, G.; Scalia, F.; De Luca, C.; Papa, M.; Maugeri, G.; D’Agata, V.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; D’Amico, A.G. The Interplay between Glioblastoma Cells and Tumor Microenvironment: New Perspectives for Early Diagnosis and Targeted Cancer Therapy. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rape, A.; Ananthanarayanan, B.; Kumar, S. Engineering Strategies to Mimic the Glioblastoma Microenvironment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 79–80, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huszthy, P.C.; Daphu, I.; Niclou, S.P.; Stieber, D.; Nigro, J.M.; Sakariassen, P.Ø.; Miletic, H.; Thorsen, F.; Bjerkvig, R. In Vivo Models of Primary Brain Tumors: Pitfalls and Perspectives. Neuro-Oncology 2012, 14, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, F.; Salinas, R.D.; Zhang, D.Y.; Nguyen, P.T.T.; Schnoll, J.G.; Wong, S.Z.H.; Thokala, R.; Sheikh, S.; Saxena, D.; Prokop, S.; et al. A Patient-Derived Glioblastoma Organoid Model and Biobank Recapitulates Inter- and Intra-tumoral Heterogeneity. Cell 2020, 180, 188–204.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoppini, L.; Buchs, P.A.; Muller, D. A Simple Method for Organotypic Cultures of Nervous Tissue. J. Neurosci. Methods 1991, 37, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpel, C. Organotypic Brain Slice Cultures: A Review. Neuroscience 2015, 305, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gähwiler, B.H.; Capogna, M.; Debanne, D.; McKinney, R.A.; Thompson, S.M. Organotypic Slice Cultures: A Technique Has Come of Age. Trends Neurosci. 1997, 20, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, B.; Wehle, A.; Hehlgans, S.; Bonn, F.; Dikic, I.; Rödel, F.; Seifert, V.; Kögel, D. Arsenic Trioxide and (−)-Gossypol Synergistically Target Glioma Stem-Like Cells via Inhibition of Hedgehog and Notch Signaling. Cancers 2019, 11, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, F.; Gaunitz, F.; Dehghani, F.; Renner, C.; Meixensberger, J.; Gutenberg, A.; Giese, A.; Schopow, K.; Hellwig, C.; Schäfer, M.; et al. Organotypic Slice Cultures of Human Glioblastoma Reveal Different Susceptibilities to Treatments. Neuro-Oncology 2013, 15, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minami, N.; Maeda, Y.; Shibao, S.; Arima, Y.; Ohka, F.; Kondo, Y.; Maruyama, K.; Kusuhara, M.; Sasayama, T.; Kohmura, E.; et al. Organotypic Brain Explant Culture as a Drug Evaluation System for Malignant Brain Tumors. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 2635–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.J.; Lizarraga, M.; Waziri, A.; Foshay, K.M. A Human Glioblastoma Organotypic Slice Culture Model for Study of Tumor Cell Migration and Patient-Specific Effects of Anti-Invasive Drugs. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 125, e53557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, V.M.; Joseph, K.; Wurm, J.; Behringer, S.P.; Garrelfs, N.; Dörner, N.; Schittenhelm, J.; Rübner, M.; Altmann, C.; Hutter, B.; et al. Human Organotypic Brain Slice Culture: A Novel Framework for Environmental Research in Neuro-Oncology. Life Sci. Alliance 2019, 2, e201900305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Sampath, D.; Lang, F.F.; Prabhu, S.; Rao, G.; Fuller, G.N.; Liu, Y.; Puduvalli, V.K. Vorinostat Modulates Cell Cycle Regulatory Proteins in Glioma Cells and Human Glioma Slice Cultures. J. Neurooncol. 2011, 105, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickl, V.; Eck, J.; Goedert, N.; Hübner, J.; Nerreter, T.; Hagemann, C.; Ernestus, R.-I.; Schulz, T.; Nickl, R.C.; Keßler, A.F.; et al. Characterization and Optimization of the Tumor Microenvironment in Patient-Derived Organotypic Slices and Organoid Models of Glioblastoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 102698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, B.; Zhang, X.; Bell, N.; Adefolaju, A.; Thang, M.; Dasari, R.; Kanchi, K.; Valdivia, A.; Yang, Y.; Buckley, A.; et al. A Living Ex Vivo Platform for Functional, Personalized Brain Cancer Diagnosis. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gritsenko, P.; Leenders, W.; Friedl, P. Recapitulating in Vivo-like Plasticity of Glioma Cell Invasion along Blood Vessels and in Astrocyte-Rich Stroma. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2017, 148, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lang, F.; Xie, X.; Prabhu, S.; Xu, J.; Sampath, D.; Aldape, K.; Fuller, G.; Puduvalli, V.K. Efficacy of adenovirally expressed soluble TRAIL in human glioma organotypic slice culture and glioma xenografts. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorcenco, V.; Krahnen, L.; Schulz, M.; Remy, J.; Kögel, D.; Temme, A.; Krügel, U.; Franke, H.; Aigner, A. Glioblastoma Tissue Slice Tandem-Cultures for Quantitative Evaluation of Inhibitory Effects on Invasion and Growth. Cancers 2020, 12, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decotret, L.R.; Shi, R.; Thomas, K.N.; Hsu, M.; Pallen, C.J.; Bennewith, K.L. Development and Validation of an Advanced Ex Vivo Brain Slice Invasion Assay to Model Glioblastoma Cell Invasion into the Complex Brain Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 976945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-Torrejon, M.A.; Gangoso, E.; Pollard, S.M. Modelling Glioblastoma Tumour-Host Cell Interactions Using Adult Brain Organotypic Slice Co-Culture. Dis. Model. Mech. 2018, 11, dmm031435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoochani, A.; Yakubov, E.; Sehm, T.; Fan, Z.; Hock, S.; Buchfelder, M.; Eyüpoglu, I.Y.; Savaskan, N.E. A Versatile Ex Vivo Technique for Assaying Tumor Angiogenesis and Microglia in the Brain. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 1838–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsume, A.; Kato, T.; Kinjo, S.; Enomoto, A.; Toda, H.; Shimato, S.; Ohka, F.; Motomura, K.; Kondo, Y.; Miyata, T.; et al. Girdin Maintains the Stemness of Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Oncogene 2012, 31, 2715–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisemann, T.; Costa, B.; Strelau, J.; Mittelbronn, M.; Angel, P.; Peterziel, H. An Advanced Glioma Cell Invasion Assay Based on Organotypic Brain Slice Cultures. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, E.N.S.; Kuechler, J.; Behling, S.; Sridhar, S.; Hirseland, E.; Tronnier, V.; Zechel, C. Maintenance of Stemlike Glioma Cells and Microglia in an Organotypic Glioma Slice Model. Neurosurgery 2015, 77, 629–643; discussion 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.M.; Kelly, M.; Odde, D.J. Glioblastoma Cells Use an Integrin- and CD44-Mediated Motor-Clutch Mode of Migration in Brain Tissue. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2024, 17, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Kallee, N.; Bergès, R.; Hein, V.; Cabaret, S.; Garcia, J.; Gros, A.; Tabouret, E.; Tchoghandjian, A.; Colin, C.; Figarella-Branger, D. Deciphering the Action of Neuraminidase in Glioblastoma Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.J.; Canoll, P.; Niswander, L.; Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B.K.; Foshay, K.; Waziri, A. Intratumoral Heterogeneity of Endogenous Tumor Cell Invasive Behavior in Human Glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 18002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, J.P.; Ravi, V.M.; Kueckelhaus, J.; Behringer, S.P.; Garrelfs, N.; Will, P.; Sun, N.; von Ehr, J.; Goeldner, J.M.; Pfeifer, D.; et al. Inhibition of metabotropic glutamate receptor III facilitates sensitization to alkylating chemotherapeutics in glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiland, D.H.; Ravi, V.M.; Behringer, S.P.; Frenking, J.H.; Wurm, J.; Joseph, K.; Garrelfs, N.; Strähle, J.; Heynckes, S.; Grauvogel, J.; et al. Tumor-Associated Reactive Astrocytes Aid the Evolution of an Immunosuppressive Environment in Glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Huang, Y.; Semtner, M.; Zhao, K.; Tan, Z.; Dzaye, O.; Kettenmann, H.; Shu, K.; Lei, T. Down-Regulation of Aquaporin-1 Mediates a Microglial Phenotype Switch Affecting Glioma Growth. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 396, 112323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravin, R.; Suarez-Meade, P.; Busse, B.; Blank, P.S.; Vivas-Buitrago, T.; Norton, E.S.; Graepel, S.; Chaichana, K.L.; Bezrukov, L.; Guerrero-Cazares, H.; et al. Perivascular Invasion of Primary Human Glioblastoma Cells in Organotypic Human Brain Slices: Human Cells Migrating in Human Brain. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2023, 164, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, G.Y. Quantitative analysis of U251MG human glioma cells invasion in organotypic brain slice co-cultures. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 2221–2229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Authors (Year) | Tissue Source | Slice Thickness (µm) | Tumour Modelling Approach | Culture Duration | Main Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xu (2011) | Human GBM surgical tissue | 300 | Native tumour tissue slice | 3–5 days | Therapeutic response (drug testing) |

| Liu (2011) | Human GBM surgical tissue | 300–350 | Native tumour tissue slice | ≤7 days | Therapeutic response (drug testing) |

| Natsume (2011) | Adult rodent brain | 300 | Cell implantation onto host slice | ≤7 days | Invasion/migration (mechanistic) |

| Raju (2015) | Human GBM surgical tissue | 300 | Native tumour tissue slice | Up to 35 days | Methodological optimisation |

| Ghoochani (2016) | Adult rodent brain | 350 | Cell implantation onto host slice | 8–10 days | Tumour–microenvironment interaction |

| Rinkenbaugh (2016) | Adult rodent brain | 300 | Cell implantation onto host slice | ≤7 days | Invasion/migration (mechanistic) |

| Minami (2017) | Adult rodent brain | 300 | Native tumour tissue slice | ≤7 days | Therapeutic response (drug testing) |

| Gritsenko (2017) | Adult rodent brain | 300 | Spheroid implantation onto host slice | 5–7 days | Invasion/migration (mechanistic) |

| Parker (2017) | Human GBM surgical tissue | 300–350 | Native tumour tissue slice | ≤15 days | Invasion/migration (quantitative) |

| Parker (2018) | Human GBM surgical tissue | 300–350 | Native tumour tissue slice | ≤14 days | Invasion/migration (quantitative) |

| Eisemann (2018) | Adult rodent brain | 300–350 | Cell implantation onto host slice | ≤7 days | Invasion/migration (quantitative) |

| Marques-Torrejon (2018) | Adult rodent brain | 300 | Microinjection of tumour cells | ≤21 days | Tumour–microenvironment interaction |

| Merz (2013) | Human GBM surgical tissue | 300–350 | Native tumour tissue slice | ≤21 days | Therapeutic response (radio/chemo) |

| Ravi (2019) | Human nontumoural cortical tissue | 350 | Microinjection of tumour cells | ≤14 days | Invasion/migration (mechanistic) |

| Linder (2019) | Adult rodent brain | 250–300 | Spheroid implantation onto host slice | ≤7 days | Therapeutic response (drug testing) |

| Heiland (2019) | Adult rodent brain | 300 | Cell implantation onto host slice | ≤10 days | Tumour–microenvironment interaction |

| Sidorcenco (2020) | Human GBM surgical tissue + adult rodent brain | 300 | Tumour slice co-culture (tandem) | ≤10 days | Invasion/migration (quantitative) |

| Hu (2020) | Human GBM surgical tissue | 300–350 | Native tumour tissue slice | ≤7 days | Therapeutic response (drug testing) |

| Maier (2021) | Human nontumoural cortical tissue | 300 | Cell implantation onto host slice | ≤10 days | Therapeutic response (radio/chemo) |

| Baeza-Kallée (2023) | Adult rodent brain | 250 | Spheroid implantation onto host slice | ≤7 days | Therapeutic response (drug testing) |

| Nickl (2023) | Human GBM surgical tissue | 350 | Native tumour tissue slice | 10–14 days | Therapeutic response (drug testing) |

| Decotret (2023) | Adult rodent brain | 300 | Spheroid implantation onto host slice | ≤7 days | Invasion/migration (quantitative) |

| Mann (2023) | Human GBM surgical tissue + adult rodent brain | 300–350 | Tumour fragment co-culture | ≤21 days | Therapeutic response (drug testing) |

| Sun (2023) | Adult rodent brain | 300 | Tumour fragment implantation | 7–14 days | Therapeutic response (drug testing) |

| Ravin (2023) | Human nontumoural cortical tissue | 350 | Cell implantation onto host slice | ≤14 days | Invasion/migration (mechanistic) |

| Anderson (2024) | Adult rodent brain | 300 | Cell co-culture onto host slice | ≤7 days | Tumour–microenvironment interaction |

| Authors (Year) | Slice Preparation | Culture Configuration | Culture Medium | Experimental Intervention(s) | Outcome Measures | Main Application | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xu (2011) | Vibratome | Submerged | Serum-containing | Chemotherapy testing | Viability/apoptosis | Drug screening | Short-term culture |

| Liu (2011) | Vibratome | Submerged | Serum-containing | Gene therapy | Viability/apoptosis | Drug screening | Short-term culture |

| Natsume (2011) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | Targeted genetic modulation | Invasion/migration | Invasion modelling | Rodent host tissue |

| Raju (2015) | Manual explants | Submerged | Multiple media compared | None (model development) | Viability/apoptosis | Methodological development | Short-term culture |

| Ghoochani (2016) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | Chemotherapy testing | Invasion/migration | Drug screening | Rodent host tissue; short-term culture |

| Rinkenbaugh (2016) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | Targeted pathway inhibition | Imaging-based growth | Drug screening | Rodent host tissue; short-term culture |

| Minami (2017) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-free | Chemotherapy testing | Invasion/migration | Drug screening | Rodent host tissue |

| Gritsenko (2017) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | None (model validation) | Invasion/migration | Invasion modelling | Rodent host tissue; short-term culture |

| Parker (2017) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Neurobasal-based | None (model development) | Invasion/migration | Invasion modelling | Short-term culture |

| Parker (2018) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Neurobasal-based | Targeted pathway inhibition | Invasion/migration | Invasion modelling | Short-term culture |

| Eisemann (2018) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | MEM-based | Targeted pathway inhibition | Invasion/migration | Invasion modelling | Rodent host tissue |

| Marques-Torrejon (2018) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-free | Chemotherapy testing | Viability/apoptosis | Tumour–microenvironment interactions | Rodent host tissue |

| Merz (2013) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | Chemotherapy/Radiotherapy | Viability/apoptosis | Drug screening | Limited tissue availability |

| Ravi (2019) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Neurobasal-based | None (model development) | Immune/TME readouts | Tumour–microenvironment interactions | Limited tissue availability |

| Linder (2019) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-free | Chemotherapy testing | Viability/apoptosis | Drug screening | Rodent host tissue |

| Heiland (2019) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-free | Immunomodulation | Immune/TME readouts | Tumour–immune interactions | Limited tissue availability |

| Sidorcenco (2020) | Vibratome | Tandem/hybrid culture | Serum-containing | Targeted pathway inhibition | Invasion/migration | Drug screening | Rodent host tissue |

| Hu (2020) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | Targeted pathway inhibition | Imaging-based growth | Methodological development | Rodent host tissue |

| Maier (2021) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | Chemotherapy testing | Viability/apoptosis | Drug screening | Limited tissue availability |

| Baeza-Kallée (2023) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | Targeted pathway inhibition | Invasion/migration | Invasion modelling | Rodent host tissue |

| Nickl (2023) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | TTFields | Viability/apoptosis | Precision oncology | Short-term culture |

| Decotret (2023) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | None (model development) | Invasion/migration | Methodological development | Rodent host tissue |

| Mann (2023) | Vibratome | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | Chemotherapy testing | Imaging-based growth | Precision oncology | Rodent host tissue |

| Ravin (2023) | Tissue chopper | Air–liquid interface | Serum-containing | None (model development) | Invasion/migration | Invasion modelling | Limited tissue availability |

| Anderson (2024) | Vibratome | Submerged | Serum-containing | Targeted pathway inhibition | Invasion/migration | Invasion modelling | Rodent host tissue |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Petralia, C.C.T.; D’amico, A.G.; D’Agata, V.; Broggi, G.; Barbagallo, G.M.V. Ex Vivo Organotypic Brain Slice Models for Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2026, 18, 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030372

Petralia CCT, D’amico AG, D’Agata V, Broggi G, Barbagallo GMV. Ex Vivo Organotypic Brain Slice Models for Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers. 2026; 18(3):372. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030372

Chicago/Turabian StylePetralia, Cateno C. T., Agata G. D’amico, Velia D’Agata, Giuseppe Broggi, and Giuseppe M. V. Barbagallo. 2026. "Ex Vivo Organotypic Brain Slice Models for Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review" Cancers 18, no. 3: 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030372

APA StylePetralia, C. C. T., D’amico, A. G., D’Agata, V., Broggi, G., & Barbagallo, G. M. V. (2026). Ex Vivo Organotypic Brain Slice Models for Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers, 18(3), 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030372