Clinical Image-Based Dosimetry of Actinium-225 in Targeted Alpha Therapy

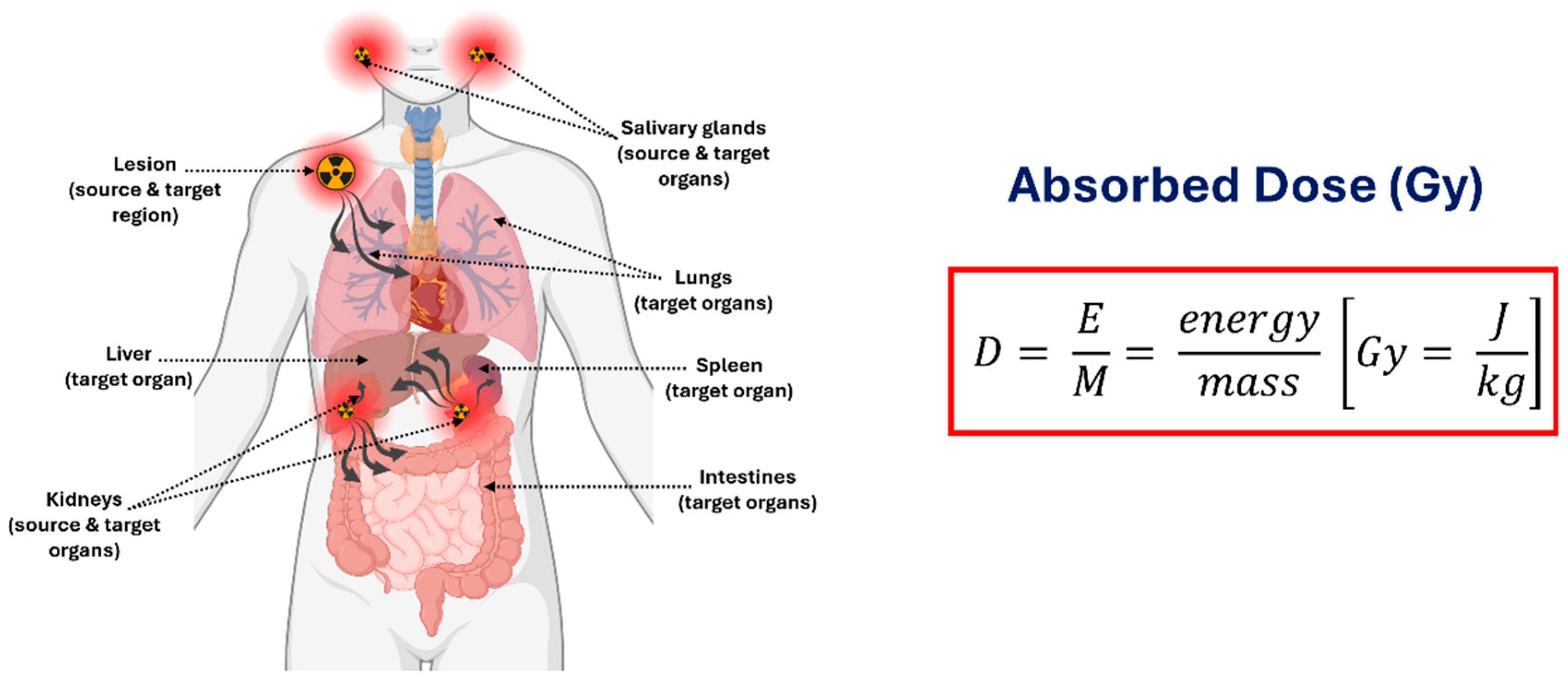

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of Ac-225 in Modern Radiopharmaceutical Therapy

1.2. Overview of Actinium-225 Production Routes

- i.

- Actinium-225 from a Thorium-229 Radionuclide Generator

- ii.

- Actinium-225 via Proton-Induced Spallation of Thorium-232

- iii.

- Actinium-225 via Gamma Irradiation of Radium-226

- iv.

- Actinium-225 via Proton Irradiation of Radium-226

1.3. Waste Management in Actinium-225 Radiopharmaceutical Production

1.4. Decay Properties of Actinium-225 for Theranostics and Dosimetry Applications

1.5. Daughter Redistribution, Recoil Effects, and Implications for Dosimetry

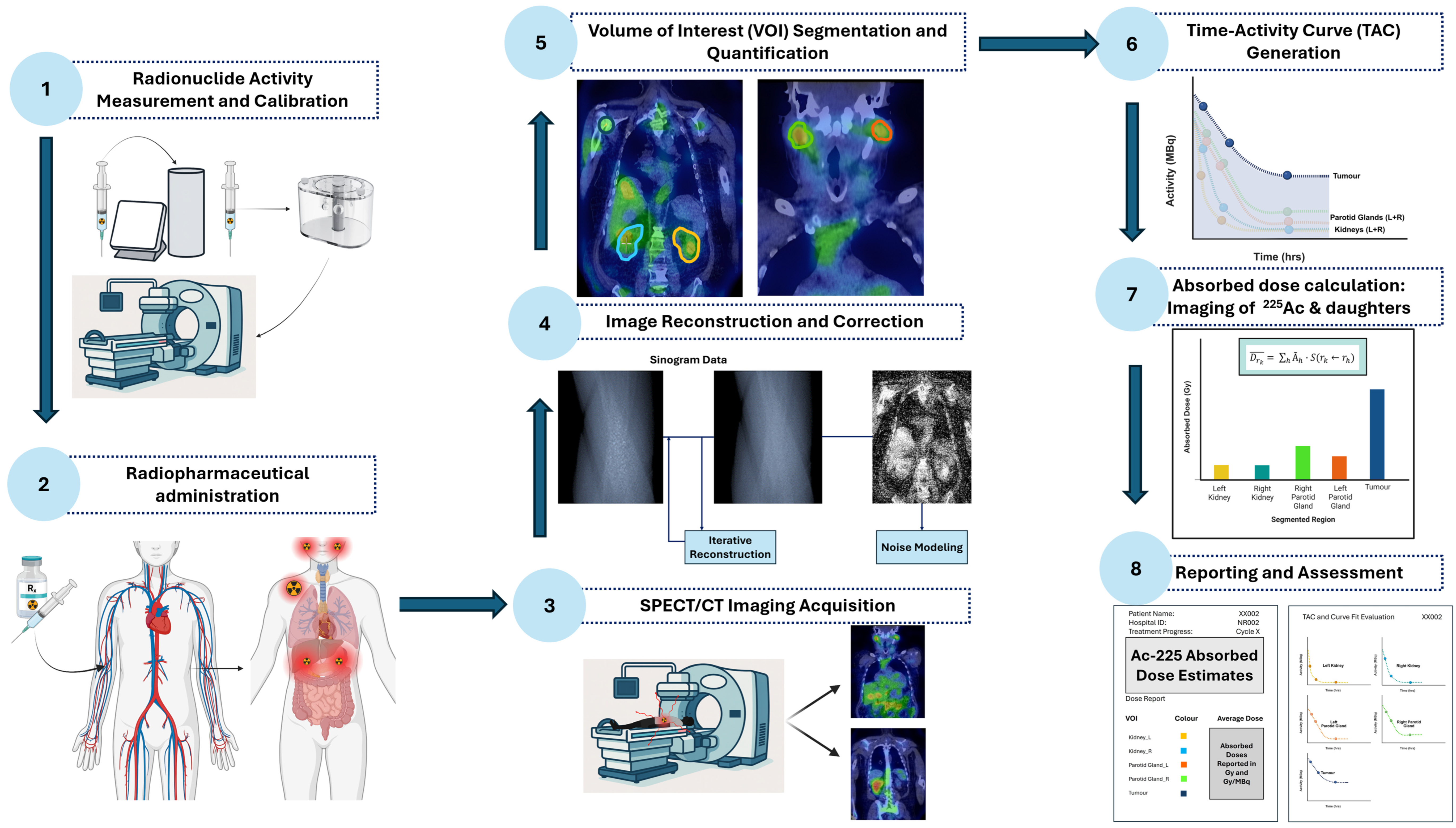

1.6. Clinical Quantitative Imaging and Dosimetry Workflow for Actinium-225

- Radionuclide Activity Measurement and Calibration—Measure administered activity using a calibrated dose calibrator.Perform gamma camera cross-calibration with phantoms to convert image counts to units of activity.

- Radiopharmaceutical Administration—Deliver the radiopharmaceutical intravenously and account for residual activity to determine the net administered dose.

- SPECT/CT Imaging Acquisition—Acquire patient imaging at clinically relevant time points, targeting primary photopeaks of 225Ac progeny.

- Image Reconstruction and Correction—Apply iterative reconstruction with corrections for attenuation, scatter, collimator-detector response (CDR) modelling, and camera-specific calibration factors.

- Volume-of-Interest Segmentation—Delineate organs and tumours using computed tomography (CT), AI-assisted, or threshold-based methods; propagate volumes of interest (VOIs) across time points to quantify activity while minimizing PVEs.

- Time-Activity Curve Generation—Extract activity in each volume of interest (VOI) over time to generate TACs, fit kinetic models, and compute time-integrated activity (TIA) and time-integrated activity coefficients (TIACs).

- Absorbed Dose Calculation—Generate voxel-level dose maps by convolving voxel S-value (VSV) kernels with TIA distributions. Compute organ- and tumour-level doses and apply relative biological effectiveness (RBE) weighting for α-particle effects.

- Reporting and Biological Assessment—Present absorbed doses with uncertainties, dose-volume metrics, and biological interpretation. Evaluate organs at risk to guide safe treatment cycles and absorbed tumour doses to incorporate patient-specific radiobiological considerations.

1.6.1. Radionuclide Activity Measurement and Calibration

1.6.2. Radiopharmaceutical Administration

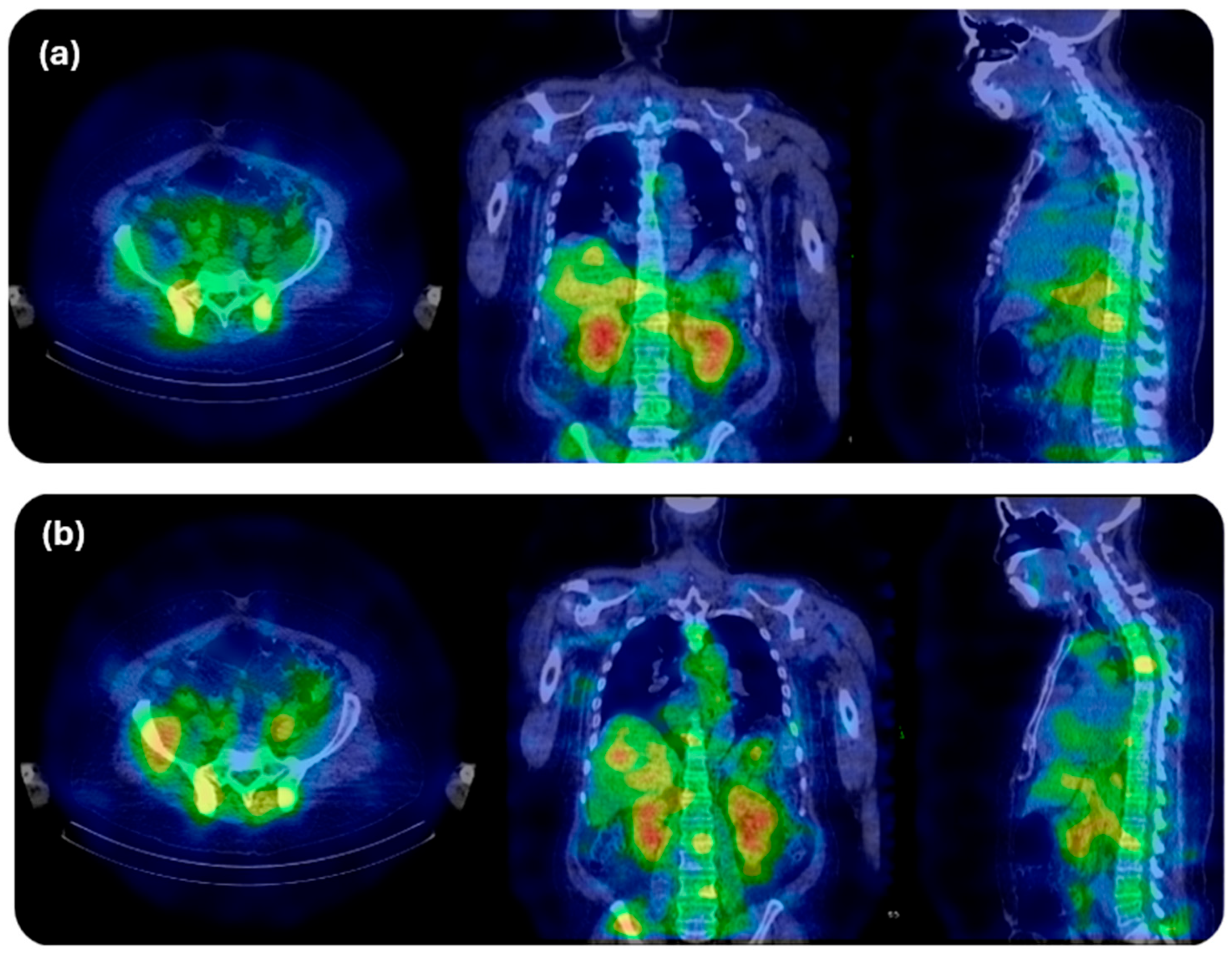

1.6.3. SPECT/CT Imaging Acquisition

1.6.4. Image Reconstruction and Correction

1.6.5. Volume of Interest Segmentation for Activity Quantification

1.6.6. Time–Activity Curve Generation

1.6.7. Absorbed Dose Calculation

1.6.8. Reporting and Biological Assessment

1.7. Actinium-225 Clinical Imaging Protocols for Dosimetry Based on Decay Emission

1.8. General Principles of Absorbed Dose Computation for Actinium-225 Dosimetry

1.8.1. Core Dosimetry Assumptions for α-Emitters

1.8.2. Limitations of Standard S-Value Methods for 225Ac

1.8.3. Formal Absorbed-Dose Framework for α-Emitters

1.8.4. Accounting for Daughter Emissions in 225Ac Dosimetry

1.8.5. Time-Integrated Activity Coefficients

1.8.6. Practical Dose Calculation for 225Ac in Clinical Dosimetry

1.8.7. Relative Biological Effectiveness Considerations and Biological Effective Dose

1.9. Biologically Effective Dose in Actinium-225 Targeted Alpha Therapy

1.10. Surrogate Imaging for Actinium-225 Radiopharmaceutical Therapy Dosimetry

1.11. Harmonisation of Activity Quantification for 225Ac Dosimetry—Provisional and Subject to Ongoing Validation

1.12. Microdosimetry in Actinium-225 Targeted Alpha Therapy

1.13. Future Directions in Tiered Dosimetry and Technological Advancements

2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Radionuclides/Isotopes | |

| 224Ac | Actinium-224 |

| 225Ac | Actinium-225 |

| 226Ac | Actinium-226 |

| 227Ac | Actinium-227 |

| 68Ga | Gallium-68 |

| 213Bi | Bismuth-213 |

| 134Ce/134La | Cerium-134/Lanthanum-134 |

| 221Fr | Francium-221 |

| 222Rn | Radon-222 |

| 225Ra | Radium-225 |

| 226Ra | Radium-226 |

| 232Th | Thorium-232 |

| 229Th | Thorium-229 |

| 233U | Uranium-233 |

| 213Po | Polonium-213 |

| 209Tl | Thallium-209 |

| Abbreviations | |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| BED | Biologically effective dose |

| CDR | Collimator–detector response |

| CFs | Calibration factors |

| CNNs | Convolutional neural networks |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| CZT | Cadmium zinc telluride |

| DL | Deep learning |

| EBRT | External beam radiotherapy |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| LET | Linear energy transfer |

| MC | Monte Carlo |

| MIRD | Medical internal radiation dose |

| MTD | Maximum tolerated dose |

| NEMA | National Electrical Manufacturers Association |

| OSEM | Ordered-subset expectation maximization |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PET/CT | Positron emission tomography/computed tomography |

| PSMA | Prostate-specific membrane antigen |

| PVEs | Partial-volume effects |

| QSPECT | Quantitative single-photon emission computed tomography |

| RBE | Relative biological effectiveness |

| RPTs | Radiopharmaceutical therapies |

| SPECT | Single-photon emission computed tomography |

| SPECT/CT | Single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography |

| TACs | Time–activity curves |

| TIA | Time-integrated activity |

| TIAC | Time-integrated activity coefficient |

| TIACs | Time-integrated activity coefficients |

| TAT | Targeted alpha therapy |

| TRT | Targeted radionuclide therapy |

| VOIs | Volumes of interest |

| VOI | Volume of interest |

| VSV | Voxel S-value |

References

- Maurer, T.; Eiber, M.; Schwaiger, M.; Gschwend, J.E. Current use of PSMA-PET in prostate cancer management. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2016, 13, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, S.; Sahoo, R.K.; Bal, C. [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-Radioligand Therapy Efficacy Outcomes in Taxane-Naïve Versus Taxane-Treated Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 1266–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, M.S.; Violet, J.; Hicks, R.J.; Ferdinandus, J.; Thang, S.P.; Akhurst, T.; Iravani, A.; Kong, G.; Kumar, A.R.; Murphy, D.G.; et al. [177Lu]-PSMA-617 radionuclide treatment in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (LuPSMA trial): A single-centre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, C.; Nilsson, S.; Heinrich, D.; Helle, S.I.; O’Sullivan, J.M.; Fosså, S.D.; Chodacki, A.; Wiechno, P.; Logue, J.; Seke, M.; et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwil, C.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Giesel, F.L.; Weis, M.; Verburg, F.A.; Mottaghy, F.; Kopka, K.; Apostolidis, C.; Haberkorn, U.; Morgenstern, A. 225Ac-PSMA-617 for PSMA-Targeted α-Radiation Therapy of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 1941–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwil, C.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Rathke, H.; Bronzel, M.; Apostolidis, C.; Weichert, W.; Haberkorn, U.; Giesel, F.L.; Morgenstern, A. Targeted α-Therapy of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer with 225Ac-PSMA-617: Dosimetry Estimate and Empiric Dose Finding. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1624–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poty, S.; Francesconi, L.C.; McDevitt, M.R.; Morris, M.J.; Lewis, J.S. α-Emitters for Radiotherapy: From Basic Radiochemistry to Clinical Studies—Part 1. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathke, H.; Winter, E.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Röhrich, M.; Giesel, F.L.; Haberkorn, U.; Morgenstern, A.; Kratochwil, C. Deescalated 225Ac-PSMA-617 Versus 177Lu/225Ac-PSMA-617 Cocktail Therapy: A Single-Center Retrospective Analysis of 233 Patients. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan-Selcuk, N.; Beydagi, G.; Demirci, E.; Ocak, M.; Celik, S.; Oven, B.B.; Toklu, T.; Karaaslan, I.; Akcay, K.; Sonmez, O.; et al. Clinical Experience with [225Ac]Ac-PSMA Treatment in Patients with [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-Refractory Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 1574–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballal, S.; Yadav, M.P.; Satapathy, S.; Raju, S.; Tripathi, M.; Damle, N.A.; Sahoo, R.K.; Bal, C. Long-term survival outcomes of salvage [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-617 targeted alpha therapy in patients with PSMA-expressing end-stage metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: A real-world study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2023, 50, 3777–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathekge, M.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Vorster, M.; Lawal, I.O.; Knoesen, O.; Mahapane, J.; Davis, C.; Mdlophane, A.; Maes, A.; Mokoala, K.; et al. mCRPC Patients Receiving 225Ac-PSMA-617 Therapy in the Post-Androgen Deprivation Therapy Setting: Response to Treatment and Survival Analysis. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauseef, J.T.; Osborne, J.; Gregos, P.; Thomas, C.; Bissassar, M.; Singh, S.; Patel, A.; Tan, A.; Naiz, M.O.; Zuloaga, J.M.; et al. Phase I/II study of 225Ac-J591 plus 177Lu-PSMA-I&T for progressive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, TPS5100. [Google Scholar]

- Tagawa, S.T.; Thomas, C.; Sartor, A.O.; Sun, M.; Stangl-Kremser, J.; Bissassar, M.; Vallabhajosula, S.; Castellanos, S.H.; Nauseef, J.T.; Sternberg, C.N.; et al. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen-Targeting Alpha Emitter via Antibody Delivery for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Phase I Dose-Escalation Study of 225Ac-J591. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagawa, S.T.; Fung, E.; Niaz, M.O.; Bissassar, M.; Singh, S.; Patel, A.; Tan, A.; Zuloaga, J.M.; Castellanos, S.H.; Nauseef, J.T.; et al. Abstract CT143: Results of combined targeting of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) with alpha-radiolabeled antibody 225Ac-J591 and beta-radiolabeled ligand 177Lu-PSMA I&T: Preclinical and initial phase 1 clinical data in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Cancer Res. 2022, 82, CT143. [Google Scholar]

- Sathekge, M.M.; Lawal, I.O.; Bal, C.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Ballal, S.; Cardaci, G.; Davis, C.; Eiber, M.; Hekimsoy, T.; Knoesen, O.; et al. Actinium-225-PSMA radioligand therapy of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (WARMTH Act): A multicentre, retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, I.A.; Glowienka, K.A.; Boll, R.A.; Deal, K.A.; Brechbiel, M.W.; Stabin, M.; Bochsler, P.N.; Mirzadeh, S.; Kennel, S.J. Comparison of actinium-225 chelates: Tissue distribution and radiotoxicity. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1999, 26, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, L.L.; Deal, K.A.; Dadachova, E.; Brechbiel, M.W. Synthesis, conjugation, and radiolabeling of a novel bifunctional chelating agent for 225Ac radioimmunotherapy applications. Bioconjug Chem. 2000, 11, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDevitt, M.R.; Ma, D.; Simon, J.; Frank, R.K.; Scheinberg, D.A. Design and synthesis of 225Ac radioimmunopharmaceuticals. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2002, 57, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, N.A.; Brown, V.; Kelly, J.M.; Amor-Coarasa, A.; Jermilova, U.; MacMillan, S.N.; Nikolopoulou, A.; Ponnala, S.; Ramogida, C.F.; Robertson, A.K.H.; et al. An Eighteen-Membered Macrocyclic Ligand for Actinium-225 Targeted Alpha Therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 14712–14717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busslinger, S.D.; Tschan, V.J.; Richard, O.K.; Talip, Z.; Schibli, R.; Müller, C. [225Ac]Ac-SibuDAB for Targeted Alpha Therapy of Prostate Cancer: Preclinical Evaluation and Comparison with [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-617. Cancers 2022, 14, 5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidkar, A.P.; Wang, S.; Bobba, K.N.; Chan, E.; Bidlingmaier, S.; Egusa, E.A.; Peter, R.; Ali, U.; Meher, N.; Wadhwa, A.; et al. Treatment of Prostate Cancer with CD46-targeted 225Ac Alpha Particle Radioimmunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 1916–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDevitt, M.R.; Thorek, D.L.J.; Hashimoto, T.; Gondo, T.; Veach, D.R.; Sharma, S.K.; Kalidindi, T.M.; Abou, D.S.; Watson, P.A.; Beattie, B.J.; et al. Feed-forward alpha particle radiotherapy ablates androgen receptor-addicted prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, I.O.; Morgenstern, A.; Vorster, M.; Knoesen, O.; Mahapane, J.; Hlongwa, K.N.; Maserumule, L.C.; Ndlovu, H.; Reed, J.D.; Popoola, G.O.; et al. Hematologic toxicity profile and efficacy of [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-617 α-radioligand therapy of patients with extensive skeletal metastases of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 3581–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerecker, B.; Tauber, R.; Knorr, K.; Heck, M.; Beheshti, A.; Seidl, C.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Pickhard, A.; Gafita, A.; Kratochwil, C.; et al. Activity and Adverse Events of Actinium-225-PSMA-617 in Advanced Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer After Failure of Lutetium-177-PSMA. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, F. The (4n+1) Radioactive Series: The Decay Products of U233. Phys. Rev. 1950, 79, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, A.C.; Cranshaw, T.E.; Demers, P.; Harvey, J.A.; Hincks, E.P.; Jelley, J.V.; May, A.N. The (4n+1) Radioactive Series. Phys. Rev. 1947, 72, 253–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerlings, M.W.; Kaspersen, F.M.; Apostolidis, C.; van der Hout, R. The feasibility of 225Ac as a source of alpha-particles in radioimmunotherapy. Nucl. Med. Commun. 1993, 14, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgenstern, A.; Apostolidis, C.; Bruchertseifer, F. Supply and Clinical Application of Actinium-225 and Bismuth-213. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2020, 50, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, C.; Molinet, R.; Rasmussen, G.; Morgenstern, A. Production of Ac-225 from Th-229 for Targeted α Therapy. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 6288–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boll, R.A.; Malkemus, D.; Mirzadeh, S. Production of actinium-225 for alpha particle mediated radioimmunotherapy. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2005, 62, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosato, M.; Favaretto, C.; Kleynhans, J.; Burgoyne, A.R.; Gestin, J.F.; van der Meulen, N.P.; Jalilian, A.; Köster, U.; Asti, M.; Radchenko, V. Alpha Atlas: Mapping global production of α-emitting radionuclides for targeted alpha therapy. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2025, 142–143, 108990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-González, M.; Akingbesote, N.; Bible, A.; Pal, D.; Sanders, B.; Ivanov, A.S.; Jansone-Popova, S.; Popovs, I.; Benny, P.; Perry, R.; et al. Development of 225Ac-doped biocompatible nanoparticles for targeted alpha therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.; Allen, K.J.H.; Prabaharan, C.B.; Ramirez, J.B.; Fiore, L.; Uppalapati, M.; Dadachova, E. Initial insights into the interaction of antibodies radiolabeled with Lutetium-177 and Actinium-225 with tumor microenvironment in experimental human and canine osteosarcoma. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2024, 134–135, 108917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liatsou, I.; Yu, J.; Bastiaannet, R.; Li, Z.; Hobbs, R.F.; Torgue, J.; Sgouros, G. 212Pb-conjugated anti-rat HER2/neu antibody against a neu-N derived murine mammary carcinoma cell line: Cell kill and RBE in vitro. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2022, 98, 1452–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.; Cai, Z.; Chan, C.; Forkan, N.; Reilly, R.M. [225Ac]Ac- and [111In]In-DOTA-trastuzumab theranostic pair: Cellular dosimetry and cytotoxicity in vitro and tumour and normal tissue uptake in vivo in NRG mice with HER2-positive human breast cancer xenografts. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2023, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, A.; Hsieh, W.; Borysenko, A.; Tieu, W.; Bartholomeusz, D.; Bezak, E. Development of [225Ac]Ac-DOTA-C595 as radioimmunotherapy of pancreatic cancer: In vitro evaluation, dosimetric assessment and detector calibration. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2023, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnuszek, P.; Karczmarczyk, U.; Maurin, M.; Sikora, A.; Zaborniak, J.; Pijarowska-Kruszyna, J.; Jaroń, A.; Wyczółkowska, M.; Wojdowska, W.; Pawlak, D.; et al. PSMA-D4 Radioligand for Targeted Therapy of Prostate Cancer: Synthesis, Characteristics and Preliminary Assessment of Biological Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacaro, J.F.; Dunckley, C.P.; Harman, S.E.; Fitzgerald, H.A.; Lakes, A.L.; Liao, Z.; Ludwig, R.C.; McBride, K.M.; Bethune, E.Y.; Younes, A.; et al. Development of 225Ac Production from Low Isotopic Dilution 229Th. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 38822–38827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IONETIX Launches Commercial Actinium-225 Production|Ac-225. Ionetix. 2024. Available online: https://www.ionetix.com/2024/06/07/ionetix-produces-first-batch-of-actinium-225/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- NorthStar Medical Radioisotopes, LLC. Actinium-225. Available online: https://www.northstarnm.com/radiopharmaceutical-therapy/actinium-225/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Multiple Production Methods Underway to Provide Actinium-225|NIDC: National Isotope Development Center. Available online: https://www.isotopes.gov/information/actinium-225 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Rearmed Bifunctional Chelating Ligand for 225Ac/155Tb Precision-Guided Theranostic Radiopharmaceuticals-H4noneunpaX. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 13705–13730. [CrossRef]

- Ramogida, C.F.; Robertson, A.K.H.; Jermilova, U.; Zhang, C.; Yang, H.; Kunz, P.; Lassen, J.; Bratanovic, I.; Brown, V.; Southcott, L.; et al. Evaluation of polydentate picolinic acid chelating ligands and an α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone derivative for targeted alpha therapy using ISOL-produced 225Ac. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2019, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wharton, L.; de Guadalupe Jaraquemada-Peláez, M.; Zhang, C.; Zeisler, J.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, C.; Osooly, M.; Radchenko, V.; Yang, H.; Lin, K.-S.; Bénard, F.; et al. H4picoopa—Robust Chelate for 225Ac/111In Theranostics. Bioconjugate Chem. 2022, 33, 1900–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, M.; Yoshii, Y.; Matsumoto, H.; Shinada, M.; Takahashi, M.; Igarashi, C.; Lassen, J.; Bratanovic, I.; Brown, V.; Southcott, L.; et al. Evaluation of Aminopolycarboxylate Chelators for Whole-Body Clearance of Free 225Ac: A Feasibility Study to Reduce Unexpected Radiation Exposure during Targeted Alpha Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Watabe, T.; Kaneda-Nakashima, K.; Shirakami, Y.; Naka, S.; Ooe, K.; Toyoshima, A.; Nagata, K.; Haberkorn, U.; Kratochwil, C.; et al. Fibroblast activation protein targeted therapy using [177Lu]FAPI-46 compared with [225Ac]FAPI-46 in a pancreatic cancer model. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Cui, Z.; Li, K.; Guan, J.; Tian, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Wu, W.; Chai, Z.; et al. A Radioluminescent Metal-Organic Framework for Monitoring 225Ac in Vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 14679–14685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolaev, S.V.; Vasiliev, A.N.; Lapshina, E.V.; Kobtsev, A.A.; Zhuikov, B.L. Production of 225Ac for medical application from 232Th-metallic targets in Nb-shells irradiated with middle-energy protons. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 8222–8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Actineer. Production Routes. Available online: https://www.actineer.com/actinium-225/production-routes (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Zielinska, B.; Apostolidis, C.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Morgenstern, A. An Improved Method for the Production of Ac-225/Bi-213 from Th-229 for Targeted Alpha Therapy. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2007, 25, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abergel, R.; An, D.; Lakes, A.; Rees, J.; Gauny, S. Actinium Biokinetics and Dosimetry: What is the Impact of Ac-227 in Accelerator-Produced Ac-225? J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2019, 50, S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.K.H.; Ramogida, C.F.; Schaffer, P.; Radchenko, V. Development of 225Ac Radiopharmaceuticals: TRIUMF Perspectives and Experiences. Curr. Radiopharm. 2018, 11, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolidis, C.; Molinet, R.; McGinley, J.; Abbas, K.; Möllenbeck, J.; Morgenstern, A. Cyclotron production of Ac-225 for targeted alpha therapy1. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2005, 62, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Production and Quality Control of Actinium-225 Radiopharmaceuticals. IAEA. 2024. Available online: http://www.iaea.org/publications/15707/production-and-quality-control-of-actinium-225-radiopharmaceuticals (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Shober, M. Regulating alpha-emitting radioisotopes and specific considerations for actinium-225 containing actinium-227. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2022, 187, 110337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidkar, A.P.; Zerefa, L.; Yadav, S.; VanBrocklin, H.F.; Flavell, R.R. Actinium-225 targeted alpha particle therapy for prostate cancer. Theranostics 2024, 14, 2969–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pommé, S.; Marouli, M.; Suliman, G.; Dikmen, H.; Van Ammel, R.; Jobbágy, V.; Dirican, A.; Stroh, H.; Paepen, J.; Bruchertseifer, F.; et al. Measurement of the 225Ac half-life. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2012, 70, 2608–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgenstern, A.; Apostolidis, C.; Kratochwil, C.; Sathekge, M.; Krolicki, L.; Bruchertseifer, F. An Overview of Targeted Alpha Therapy with Actinium-225 and Bismuth-213. Curr. Radiopharm. 2018, 11, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kruijff, R.M.; Wolterbeek, H.T.; Denkova, A.G. A Critical Review of Alpha Radionuclide Therapy—How to Deal with Recoiling Daughters? Pharmaceuticals 2015, 8, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozempel, J.; Mokhodoeva, O.; Vlk, M. Progress in Targeted Alpha-Particle Therapy. What We Learned about Recoils Release from In Vivo Generators. Molecules 2018, 23, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Nolasco, M.; Morales-Avila, E.; Cruz-Nova, P.; Katti, K.V.; Ocampo-García, B. Nanoradiopharmaceuticals Based on Alpha Emitters: Recent Developments for Medical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruijff RMde Raavé, R.; Kip, A.; Molkenboer-Kuenen, J.; Morgenstern, A.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Heskamp, S.; Denkova, A.G. The in vivo fate of 225Ac daughter nuclides using polymersomes as a model carrier. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, D.; De Gregorio, R.; Pratt, E.C.; Bell, A.; Michel, A.; Lewis, J.S. Examination of the PET in vivo generator 134Ce as a theranostic match for 225Ac. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 51, 4015–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.; Jaggi, J.S.; O’Donoghue, J.A.; Ruan, S.; McDevitt, M.; Larson, S.M.; Scheinberg, D.A.; Humm, J.L. Renal uptake of bismuth-213 and its contribution to kidney radiation dose following administration of actinium-225-labeled antibody. Phys. Med. Biol. 2011, 56, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathekge, M.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Knoesen, O.; Reyneke, F.; Lawal, I.; Lengana, T.; Davis, C.; Mahapane, J.; Corbett, C.; Vorster, M.; et al. 225Ac-PSMA-617 in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced prostate cancer: A pilot study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea-Lager, D.E.; MacLennan, S.; Dierckx, R.; Fanti, S. The EANM Focus 5 consensus on ‘molecular imaging and theranostics in prostate cancer’: The future begins today. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 51, 1462–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulik, M.; Kuliński, R.; Tabor, Z.; Brzozowska, B.; Łaba, P.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Morgenstern, A.; Królicki, L.; Kunikowska, J. Quantitative SPECT/CT imaging of actinium-225 for targeted alpha therapy of glioblastomas. EJNMMI Phys. 2024, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapi, S.E.; Scott, P.J.H.; Scott, A.M.; Windhorst, A.D.; Zeglis, B.M.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Baum, R.P.; Buatti, J.M.; Giammarile, F.; Kiess, A.P.; et al. Recent Advances and Impending Challenges for the Radiopharmaceutical Sciences in Oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, e236–e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polson, L.; Rahmim, A.; Uribe, C. Quantitative Ac-225 SPECT Imaging and Reconstruction: What Photopeak Should We Use? J. Nucl. Med. 2025, 66, 252208. [Google Scholar]

- Liubchenko, G.; Böning, G.; Zacherl, M.; Rumiantcev, M.; Unterrainer, L.M.; Gildehaus, F.J.; Brendel, M.; Resch, S.; Bartenstein, P.; Ziegler, S.; et al. Image-based dosimetry for [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-I&T therapy and the effect of daughter-specific pharmacokinetics. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 51, 2504–2514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sgouros, G.; Ulaner, G.; Delie, T.; Kotiah, S.; Ferreira, D.; Ma, K.; Rearden, J.; Moran, S.; Sneeden, E.; He, B.; et al. 225Ac-DOTATATE Dosimetry Results from Part 1 of the ACTION-1 Trial. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, P129. [Google Scholar]

- Gosewisch, A.; Schleske, M.; Gildehaus, F.J.; Berg, I.; Kaiser, L.; Brosch, J.; Bartenstein, P.; Todica, A.; Ilhan, H.; Böning, G.; et al. Image-based dosimetry for 225Ac-PSMA-I&T therapy using quantitative SPECT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 1260–1261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dewaraja, Y.K.; Frey, E.C.; Sgouros, G.; Brill, A.B.; Roberson, P.; Zanzonico, P.B.; Ljungberg, M. MIRD pamphlet No. 23: Quantitative SPECT for patient-specific 3-dimensional dosimetry in internal radionuclide therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2012, 53, 1310–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrecchia-Ramos, E.; Morel, O.; Ginet, M.; Retif, P.; Ben Mahmoud, S. Clinical validation of an AI-based automatic quantification tool for lung lobes in SPECT/CT. EJNMMI Phys. 2023, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekshmi, G.; Khan, D.; Sagar, S.; Mahalik, A.; Goriparthi, L.; Krishna, J.; Dhiman, A.; Kundu, N.; Roy, A. Utility of AI (Artificial Intelligence) tool for automatic segmentation and calculation of quantitative PET parameters compared to conventional manual segmentation in patients of Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. J. Nucl. Med. 2025, 66, 252269. [Google Scholar]

- Besemer, A.E.; Titz, B.; Grudzinski, J.; Weichert, J.P.; Kuo, J.S.; Robins, H.I.; Hall, L.T.; Bednarz, P. Impact of PET and MRI threshold-based tumor volume segmentation on targeted radionuclide therapy patient-specific dosimetry using CLR1404. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 6008–6025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquis, H.; Willowson, K.; Bailey, D. Partial volume effect in SPECT & PET imaging and impact on radionuclide dosimetry estimates. Asia Ocean. J. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2023, 11, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kurkowska, S.; Brosch-Lenz, J.; Dewaraja, Y.K.; Frey, E.; Sunderland, J.; Uribe, C. An International Study of Factors Affecting Variability of Dosimetry Calculations, Part 4: Impact of Fitting Functions in Estimated Absorbed Doses. J. Nucl. Med. 2025, 66, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delker, A.; Schleske, M.; Liubchenko, G.; Berg, I.; Zacherl, M.J.; Brendel, M.; Gildehaus, F.J.; Rumiantcev, M.; Resch, S.; Hürkamp, K.; et al. Biodistribution and dosimetry for combined [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-I&T/[225Ac]Ac-PSMA-I&T therapy using multi-isotope quantitative SPECT imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2023, 50, 1280–1290. [Google Scholar]

- Gosewisch, A.; Ilhan, H.; Tattenberg, S.; Mairani, A.; Parodi, K.; Brosch, J.; Kaiser, L.; Gildehaus, F.J.; Todica, A.; Ziegler, S.; et al. 3D Monte Carlo bone marrow dosimetry for Lu-177-PSMA therapy with guidance of non-invasive 3D localization of active bone marrow via Tc-99m-anti-granulocyte antibody SPECT/CT. EJNMMI Res. 2019, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhlen, T.T.; Cerutti, F.; Chin, M.P.W.; Fassò, A.; Ferrari, A.; Ortega, P.G.; Mairani, A.; Sala, P.R.; Smirnov, G.; Vlachoudis, V.; et al. The FLUKA Code: Developments and Challenges for High Energy and Medical Applications. Nucl. Data Sheets 2014, 120, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassmann, M.; Chiesa, C.; Flux, G.; Bardiès, M.; EANM Dosimetry Committee. EANM Dosimetry Committee guidance document: Good practice of clinical dosimetry reporting. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2011, 38, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergnaud, L.; Dewaraja, Y.K.; Giraudet, A.L.; Badel, J.N.; Sarrut, D. A review of 177Lu dosimetry workflows: How to reduce the imaging workloads? EJNMMI Phys. 2024, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA Issues New Guidance For Clinical Trial Dosage Of Oncology Therapeutic Radiopharmaceuticals. Available online: https://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/fda-issues-new-guidance-for-clinical-trial-dosage-of-oncology-therapeutic-radiopharmaceuticals-0001 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Benabdallah, N.; Scheve, W.; Dunn, N.; Silvestros, D.; Schelker, P.; Abou, D.; Jammalamadaka, U.; Laforest, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; et al. Practical Considerations for Quantitative Clinical SPECT/CT Imaging of Alpha Particle Emitting Radioisotopes. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgouros, G.; Ballangrud, A.M.; Jurcic, J.G.; McDevitt, M.R.; Humm, J.L.; Erdi, Y.E.; Mehta, B.M.; Finn, R.D.; Larson, S.M.; Scheinberg, D.A.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and dosimetry of an alpha-particle emitter labeled antibody: 213Bi-HuM195 (anti-CD33) in patients with leukemia. J. Nucl. Med. 1999, 40, 1935–1946. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, P.W.; Rajon, D.A.; Shah, A.P.; Jokisch, D.W.; Inglis, B.A.; Bolch, W.E. Site-specific variability in trabecular bone dosimetry: Considerations of energy loss to cortical bone. Med. Phys. 2002, 29, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolch, W.E.; Patton, P.W.; Rajon, D.A.; Shah, A.P.; Jokisch, D.W.; Inglis, B.A. Considerations of marrow cellularity in 3-dimensional dosimetric models of the trabecular skeleton. J. Nucl. Med. 2002, 43, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.P.; Rajon, D.A.; Patton, P.W.; Jokisch, D.W.; Bolch, W.E. Accounting for beta-particle energy loss to cortical bone via paired-image radiation transport (PIRT). Med. Phys. 2005, 32, 1354–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgouros, G.; Roeske, J.C.; McDevitt, M.R.; Palm, S.; Allen, B.J.; Fisher, D.R.; Brill, A.B.; Song, H.; Howell, R.W.; Akabani, G. MIRD Pamphlet No. 22 (Abridged): Radiobiology and Dosimetry of α-Particle Emitters for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2010, 51, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolch, W.E.; Eckerman, K.F.; Sgouros, G.; Thomas, S.R. MIRD Pamphlet No. 21: A Generalized Schema for Radiopharmaceutical Dosimetry—Standardization of Nomenclature. J. Nucl. Med. 2009, 50, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgouros, G.; He, B.; Ray, N.; Ludwig, D.L.; Frey, E.C. Dosimetric impact of Ac-227 in accelerator-produced Ac-225 for alpha-emitter radiopharmaceutical therapy of patients with hematological malignancies: A pharmacokinetic modeling analysis. EJNMMI Phys. 2021, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel, H.G.; Clement, C.; DeLuca, P. ICRP Publication 110. Realistic reference phantoms: An ICRP/ICRU joint effort. A report of adult reference computational phantoms. Ann. ICRP. 2009, 39, 1–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamacher, K.A.; Sgouros, G. A schema for estimating absorbed dose to organs following the administration of radionuclides with multiple unstable daughters: A matrix approach. Med. Phys. 1999, 26, 2526–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinendegen, L.E.; McClure, J.J. Alpha-Emitters for Medical Therapy: Workshop of the United States Department of Energy: Denver, Colorado, 30–31 May 1996. Radiat. Res. 1997, 148, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantel, E. MIRD Monograph: Radiobiology and Dosimetry for Radiopharmaceutical Therapy with Alpha-Particle Emitters. J. Nucl. Med. Technol. 2016, 44, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hu, Z.; Qu, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, S.; Hu, A.; Qiu, R.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, J. Evaluation of relative biological effectiveness of 225Ac and its decay daughters with Monte Carlo track structure simulations. EJNMMI Phys. 2025, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumiantcev, M.; Li, W.B.; Lindner, S.; Liubchenko, G.; Resch, S.; Bartenstein, P.; Ziegler, S.I.; Böning, G.; Delke, A. Estimation of relative biological effectiveness of 225Ac compared to 177Lu during [225Ac]Ac-PSMA and [177Lu]Lu-PSMA radiopharmaceutical therapy using TOPAS/TOPAS-nBio/MEDRAS. EJNMMI Phys. 2023, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruigrok, E.A.M.; Tamborino, G.; de Blois, E.; Roobol, S.J.; Verkaik, N.; De Saint-Hubert, M.; Konijnenberg, M.W.; van Weerden, W.M.; de Jong, M.; Nonnekens, J. In vitro dose effect relationships of actinium-225- and lutetium-177-labeled PSMA-I&T. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 3627–3638. [Google Scholar]

- Zaider, M.; Rossi, H.H. The synergistic effects of different radiations. Radiat. Res. 1980, 83, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belli, M.L.; Sarnelli, A.; Mezzenga, E.; Cesarini, F.; Caroli, P.; Di Iorio, V.; Strigari, L.; Cremonesi, M.; Romeo, A.; Nicolini, S.; et al. Targeted Alpha Therapy in mCRPC (Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer) Patients: Predictive Dosimetry and Toxicity Modeling of 225Ac-PSMA (Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen). Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 531660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalloul, W.; Ghizdovat, V.; Stolniceanu, C.R.; Ionescu, T.; Grierosu, I.C.; Pavaleanu, I.; Moscalu, M.; Stefanescu, C. Targeted Alpha Therapy: All We Need to Know about 225Ac’s Physical Characteristics and Production as a Potential Theranostic Radionuclide. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalloul, W.; Ghizdovat, V.; Saviuc, A.; Jalloul, D.; Grierosu, I.C.; Stefanescu, C. Targeted Alpha Therapy: Exploring the Clinical Insights into [225Ac]Ac-PSMA and Its Relevance Compared with [177Lu]Lu-PSMA in Advanced Prostate Cancer Management. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. Relative Efficacy of 225Ac-PSMA-617 and 177Lu-PSMA-617 in Prostate Cancer Based on Subcellular Dosimetry. Mol. Imaging Radionucl. Ther. 2022, 31, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanzonico, P. Dosimetry for Radiopharmaceutical Therapy: Practical Implementation, From the AJR Special Series on Quantitative Imaging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2025, 225, e2431873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanzonico, P.B.; Bigler, R.E.; Sgouros, G.; Strauss, A. Quantitative SPECT in radiation dosimetry. Semin. Nucl. Med. 1989, 19, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.L.; Willowson, K.P. Quantitative SPECT/CT: SPECT joins PET as a quantitative imaging modality. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol Imaging 2014, 41, S17–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandervoort, E.; Celler, A.; Harrop, R. Implementation of an iterative scatter correction, the influence of attenuation map quality and their effect on absolute quantitation in SPECT. Phys. Med. Biol. 2007, 52, 1527–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.L.; Willowson, K.P. An evidence-based review of quantitative SPECT imaging and potential clinical applications. J. Nucl. Med. 2013, 54, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seret, A.; Nguyen, D.; Bernard, C. Quantitative capabilities of four state-of-the-art SPECT-CT cameras. EJNMMI Res. 2012, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.; Celler, A. A multivendor phantom study comparing the image quality produced from three state-of-the-art SPECT-CT systems. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2012, 33, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.; Shcherbinin, S.; Celler, A. A multi-center phantom study comparing image resolution from three state-of-the-art SPECT-CT systems. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2009, 16, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collarino, A.; Pereira Arias-Bouda, L.M.; Valdés Olmos, R.A.; van der Tol, P.; Dibbets-Schneider, P.; de Geus-Oei, L.F.; van Velden, F.H.P. Experimental validation of absolute SPECT/CT quantification for response monitoring in breast cancer. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, 2143–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, J.; Claeys, W.; Denis-bacelar, A.; Hristova, I.; Lassmann, M.; Koole, M.; Tran-Gia, J. An EANM/EARL accreditation standard for quantitative Lu-177 SPECT-CT imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2025, 66, 251783. [Google Scholar]

- Zvereva, A.; Kamp, F.; Schlattl, H.; Zankl, M.; Parodi, K. Impact of interpatient variability on organ dose estimates according to MIRD schema: Uncertainty and variance-based sensitivity analysis. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, 3391–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosch-Lenz, J.; Kurkowska, S.; Frey, E.; Dewaraja, Y.K.; Sunderland, J.; Uribe, C. An International Study of Factors Affecting Variability of Dosimetry Calculations, Part 3: Contribution from Calculating Absorbed Dose from Time-Integrated Activity. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desy, A.; Bouvet, G.F.; Croteau, É.; Lafrenière, N.; Turcotte, É.E.; Després, P.; Beauregard, J. Quantitative SPECT (QSPECT) at high count rates with contemporary SPECT/CT systems. EJNMMI Phys. 2021, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kangasmaa, T.S.; Constable, C.; Hippeläinen, E.; Sohlberg, A.O. Multicenter evaluation of single-photon emission computed tomography quantification with third-party reconstruction software. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2016, 37, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, I.S.; Hoffmann, S.A. Activity concentration measurements using a conjugate gradient (Siemens xSPECT) reconstruction algorithm in SPECT/CT. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2016, 37, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatting, G.; Kletting, P.; Reske, S.N.; Hohl, K.; Ring, C. Choosing the optimal fit function: Comparison of the Akaike information criterion and the F-test. Med. Phys. 2007, 34, 4285–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiansyah, D.; Yousefzadeh-Nowshahr, E.; Kind, F.; Beer, A.J.; Ruf, J.; Glatting, G.; Mix, M. Single-Time-Point Renal Dosimetry Using Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Modeling and Population-Based Model Selection in [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 Therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch-Lenz, J.; Delker, A.; Völter, F.; Unterrainer, L.M.; Kaiser, L.; Bartenstein, P.; Ziegler, S.; Rahmim, A.; Uribe, C.; Böning, G. Toward Single-Time-Point Image-Based Dosimetry of 177Lu-PSMA-617 Therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIRD Cellular S Values. Available online: https://snmmi.org/Web/iCore/Store/StoreLayouts/Item_Detail.aspx?iProductCode=0-932004-46-6 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Goddu, S.M.; Howell, R.W.; Rao, D.V. Cellular dosimetry: Absorbed fractions for monoenergetic electron and alpha particle sources and S-values for radionuclides uniformly distributed in different cell compartments. J. Nucl. Med. 1994, 35, 303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Polig, E. Localized Alpha-Dosimetry for Cancer Induction Studies; Priest, N.D., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1985; pp. 269–284. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-94-009-4920-1_25 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Roesch, W.C. Microdosimetry of internal sources. Radiat. Res. 1977, 70, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinchcomb, T.G.; Roeske, J.C. Analysis of survival of C-18 cells after irradiation in suspension with chelated and ionic bismuth-212 using microdosimetry. Radiat. Res. 1994, 140, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellerer, A.M.; Chmelevsky, D. Criteria for the applicability of LET. Radiat. Res. 1975, 63, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, W.; Li, W.B.; Friedland, W.; Miller, B.W.; Madas, B.; Bardiès, M.; Balásházy, I. Internal microdosimetry of alpha-emitting radionuclides. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2020, 59, 29–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.B.; Bouvier-Capely, C.; Saldarriaga Vargas, C.; Andersson, M.; Madas, B. Heterogeneity of dose distribution in normal tissues in case of radiopharmaceutical therapy with alpha-emitting radionuclides. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2022, 61, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri, B.; Wu, H.; Dhawan, A.P.; Du, P.; Howell, R.W.; SNMMI MIRD Committee. MIRD pamphlet No. 25: MIRDcell V2 0 software tool for dosimetric analysis of biologic response of multicellular populations. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goddu, S.M.; Rao, D.V.; Howell, R.W. Multicellular Dosimetry for Micrometastases: Dependence of Self-Dose Versus Cross-Dose to Cell Nuclei on Type and Energy of Radiation and Subcellular Distribution of Radionuclides. J. Nucl. Med. 1994, 35, 521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Li, M.; Bednarz, B.; Schultz, M.K. Modeling Cell and Tumor-Metastasis Dosimetry with the Particle and Heavy Ion Transport Code System (PHITS) Software for Targeted Alpha-Particle Radionuclide Therapy. Radiat. Res. 2018, 190, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koniar, H.; Miller, C.; Rahmim, A.; Schaffer, P.; Uribe, C. A GATE simulation study for dosimetry in cancer cell and micrometastasis from the 225Ac decay chain. EJNMMI Phys. 2023, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.B.; Mirando, D.M.; Dewaraja, Y.K. Accuracy and uncertainty analysis of reduced time point imaging effect on time-integrated activity for 177Lu-DOTATATE PRRT in patients and clinically realistic simulations. EJNMMI Res. 2023, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devasia, T.P.; Dewaraja, Y.K.; Frey, K.A.; Wong, K.K.; Schipper, M.J. A Novel Time–Activity Information-Sharing Approach Using Nonlinear Mixed Models for Patient-Specific Dosimetry with Reduced Imaging Time Points: Application in SPECT/CT After 177Lu-DOTATATE. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.M.; Amor-Coarasa, A.; Sweeney, E.; Wilson, J.J.; Causey, P.W.; Babich, J.W. A suitable time point for quantifying the radiochemical purity of 225Ac-labeled radiopharmaceuticals. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2021, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curkic, S. Evaluation of Internal Dosimetry for 225Ac Using One Single Measurement Based on 111In Imaging. 2021. Available online: http://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/9043414 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Li, J.Y.; Zhou, W.M.; Xiong, X.A.; Yuan, C.Z.; Zhou, X.C. High-resolution three-dimensional SPECT image reconstruction for 225Ac therapy via OSEM algorithm. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2025, 334, 7019–7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Rowe, S.P.; Du, Y. SPECTnet: A deep learning neural network for SPECT image reconstruction. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch-Lenz, J.; Yousefirizi, F.; Zukotynski, K.; Beauregard, J.M.; Gaudet, V.; Saboury, B.; Rahmim, A.; Uribe, C. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Theranostics:: Toward Routine Personalized Radiopharmaceutical Therapies. PET Clin. 2021, 16, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starmans, M.P.A.; van der Voort, S.R.; Castillo Tovar, J.M.; Veenland, J.F.; Klein, S.; Niessen, W.J. Chapter 18-Radiomics: Data mining using quantitative medical image features. In Handbook of Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention; Zhou, S.K., Rueckert, D., Fichtinger, G., Eds.; The Elsevier and MICCAI Society Book Series; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 429–456. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128161760000235 (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Gudi, S.; Ghosh-Laskar, S.; Agarwal, J.P.; Chaudhari, S.; Rangarajan, V.; Nojin Paul, S.; Upreti, R.; Murthy, V.; Budrukkar, A.; Gupta, T. Interobserver Variability in the Delineation of Gross Tumour Volume and Specified Organs-at-risk During IMRT for Head and Neck Cancers and the Impact of FDG-PET/CT on Such Variability at the Primary Site. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2017, 48, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.; Jiménez-Franco, L.D.; Schroeder, M.; Kluge, A.; Bronzel, M.; Kimiaei, S. Automated and robust organ segmentation for 3D-based internal dose calculation. EJNMMI Res. 2021, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.; Caroli, A.; Quach, L.V.; Petzold, K.; Bozzetto, M.; Serra, A.L.; Remuzzi, G.; Remuzzi, A. Kidney volume measurement methods for clinical studies on autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, S.; Gafita, A.; Zhao, Y.; Mercolli, L.; Cheng, F.; Rauscher, I.; D’Alessandria, C.; Seifert, R.; Afshar-Oromieh, A.; Rominger, A. Pre-therapy PET-based voxel-wise dosimetry prediction by characterizing intra-organ heterogeneity in PSMA-directed radiopharmaceutical theranostics. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 51, 3450–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Gafita, A.; Dong, C.; Zhao, Y.; Tetteh, G.; Menze, B.H.; Ziegler, S.; Weber, W.; Afshar-Oromieh, A.; Rominger, A. Application of machine learning to pretherapeutically estimate dosimetry in men with advanced prostate cancer treated with 177Lu-PSMA I&T therapy. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 4064–4072. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, C.V.; Chen, Y.; Rauscher, I.; Xue, S.; Gafita, A.; Hu, J.; Seifert, R.; Mercolli, L.; Brosch-Lenz, J.; Hong, J. Characterization of Effective Half-Life for Instant Single-Time-Point Dosimetry Using Machine Learning. J. Nucl. Med. 2025, 66, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrut, D.; Badel, J.N.; Halty, A.; Garin, G.; Perol, D.; Cassier, P.; Blay, J.; Kryza, D.; Giraudet, A. 3D absorbed dose distribution estimated by Monte Carlo simulation in radionuclide therapy with a monoclonal antibody targeting synovial sarcoma. EJNMMI Phys. 2017, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänscheid, H.; Lapa, C.; Buck, A.K.; Lassmann, M.; Werner, R.A. Absorbed dose estimates from a single measurement one to three days after the administration of 177Lu-DOTATATE/-TOC. Nuklearmedizin 2017, 56, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vergnaud, L.; Giraudet, A.L.; Moreau, A.; Salvadori, J.; Imperiale, A.; Baudier, T.; Badel, J.; Sarrut, D. Patient-specific dosimetry adapted to variable number of SPECT/CT time-points per cycle for 177Lu-DOTATATE therapy. EJNMMI Phys. 2022, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorz, A.; Rossato, M.A.; Turco, P.; Colombo Gomez, L.M.; Bettinelli, A.; De Monte, F.; Paiusco, M.; Zucchetta, P.; Cecchin, D. Performance evaluation of the 3D-ring cadmium-zinc-telluride (CZT) StarGuide system according to the NEMA NU 1-2018 standard. EJNMMI Phys. 2024, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, V.; Luong, K. 177Lu quantitative studies on StarGuide SPECT/CT system: Conversion factor dependencies on acquisition and BSREM-based (QClear) reconstruction parameters. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, P1307. [Google Scholar]

| Production Route | Yield/Availability | Isotopic Purity | Key Radiological and Dosimetry Characteristics | Clinical Theranostic Considerations | Advantages | Limitations/Challenges | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 229Th radionuclide generator | Moderate; clinically validated | Very high purity. Essentially no 227Ac | 225Ac T½ = 9.92 d; α-emitter (Eα ≈ 5.8 MeV); decays to 221Fr → 217At → 213Bi (T½ = 45.6 min, α-emitter); high specific activity (~0.2–0.3 TBq/µmol) | Provides high-quality 225Ac for targeted α-therapy; 213Bi available for theranostic applications; well-defined dosimetry due to negligible long-lived impurities | Clinically established generator system; carrier-free 225Ac; dual-use for α-therapy and theranostics | Limited 229Th global supply; long parent half-life limits production scale | Active: JRC Karlsruhe (DE), ORNL (USA), IPPE (RU); supply constrained |

| 232Th spallation | High; multi-Curie scale | Moderate purity. 227Ac impurity ~0.1–0.2% | 225Ac T½ = 9.92 d; α-emitter; 227Ac T½ = 21.77 y contributes long-term dose; α-energy ~5–6 MeV; specific activity slightly reduced due to 227Ac | Suitable for high-volume clinical supply; dosimetry affected by long-lived 227Ac; careful radiation safety and waste management required | Capable of producing multi-Curie quantities; meets future demand | Trade-off between yield and isotopic purity; regulatory and waste management challenges due to 227Ac | Implemented at U.S. Tri-Labs (ORNL, LANL, BNL); large-scale production |

| 226Raproton irradiation | Medium–high; ~5 GBq per 50 mg 226Ra, 24 h at 100 μA | High purity. Negligible 227Ac | 225Ac T½ = 9.92 d; α-emitter; short-lived impurities 226Ac T½ = 29 h, 224Ac T½ = 2.9 h decay during post-irradiation cooling; high specific activity | Produces clinically suitable 225Ac for α-therapy; predictable dosimetry; minimal long-lived impurity contribution | High-purity 225Ac; scalable; cyclotron-based | Requires handling of 226Ra and gaseous 222Rn; specialized cyclotron and radiochemistry infrastructure | Widely used research and production route; mature |

| 226RaGamma irradiation | Low; not demonstrated at clinical scale | Potentially high purity. Unproven at scale. | 225Ac T½ = 9.92 d; α-emitter; intermediate 225Ra T½ = 14.9 d contributes to ingrowth dose | Theoretically capable of producing high-purity 225Ac; dosimetry is predictable once the process is optimized | Non-proton alternative; potential for high-purity production | Limited by gamma source intensity; no proof-of-principle for high-activity clinical-scale production | Exploratory/proof-of-concept stage |

| References | [27,28,29,49,54,55] |

| Study/Reference | Photopeak energy (keV) and Window Width (%) | Imaging Time Points Post-Injection | Model and Manufacturer | Reconstruction Algorithm | Reported Absorbed Doses/Key Observations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bismuth-213 | Francium-221 | X-Ray Emissions | |||||

| Liubchenko et al. [70] | 440 keV (20%) | 218 keV (20%) | 78 keV (50%) | 24 h, 48 h | Siemens Symbia T2 SPECT/CT (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) | In-house MAP-MLEM algorithm | Mean kidney and lesion absorbed doses. 221Fr & 213Bi images: 0.17 ± 0.06 Sv(RBE=5)/MBq & 0.36 ± 0.1 Sv(RBE=5)/MBq Either 221Fr/213Bi images: 0.16 ± 0.05/0.18 ± 0.06 Sv(RBE=5)/MBq & 0.36 ± 0.1/0.38 ± 0.1 Sv(RBE=5)/MBq |

| Delker et al. [79] | 440 keV (10%) | Not imaged | Not imaged | 24 h | Symbia Intevo T16 SPECT/CT (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) | In-house MAP-EM algorithms | Kidney and lesion absorbed doses 225Ac: 0.28 ± 0.14 & 0.22 ± 0.21 Sv(RBE=5)MBq |

| Gosewisch et al. [72] | 440 (20%) | 218 keV (10%) | Not imaged | 24 h | Siemens Symbia Intevo T16 SPECT/CT (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) | MAP algorithm | Left kidney, right kidney and lesion absorbed doses 177Lu: 0.27, 0.24 & 0.38 Gy/GBq 0.18, 0.1 & 0.26 Sv(RBE=5)/MBq |

| Tulik et al. [67] | 444 keV (10%) | 217 KeV (10%) | 78 keV (20%) | Phantom study | Siemens Symbia T6 SPECT/CT (Siemens Healthineers, Germany) | OSEM FLASH 3D algorithm (Siemens Healthineers) | Phantom calibration (Jaszczak and 3D-printed tumour model), activity quantification within 10% accuracy |

| Benabdallah et al. [85] | 410 keV (±6.1%) [GE Healthcare] 444 keV (±5%) [Siemens Healthineers] | 218 keV (±8%) [GE Healthcare] 217 keV (±8%) [Siemens Healthineers] | 80 keV (±20%) [GE Healthcare] 82 keV (±20%) [Siemens Healthineers] | Phantom study | Discovery 670 SPECT/CT (GE Healthcare) and Siemens Symbia T6 SPECT/CT (Siemens Healthineers, Germany) | 2D-OSEM algorithm (GE Healthcare) 3D-OSEM algorithm (Siemens Healthineers) | Evaluated detection limits, reconstruction, and sensitivity across multiple gamma cameras |

| Sgorous et al. [71] | 440 keV (20%) | 218 keV (20%) | 92 keV (25%) | 4 ± 1 h, 24 ± 2 h, 168 ± 24 h | Manufacturer unspecified | Dual-radionuclide quantitative SPECT reconstruction used | Weighted absorbed dose coefficients for source organs and lesions (Mean RBE = 5): Spleen (1.1 Gy/MBq), kidneys (0.45 Gy/MBq), liver (0.30 Gy/MBq), red marrow (0.032 Gy/MBq), 11 Tumours (1.0–4.8 Gy) |

| Polson et al. [69] | 440 keV (20%) | 218 keV (20%) | Not imaged | 6 h, 20.5 h, 76.5 h, 284.6 h | Simulation study (SIMIND MC program) | MLEM algorithm | Time-integrated activity and uncertainty for 3 lesions: Lesion 1 (11.2 MBq·h ± 14.02%), Lesion 2 (0.6 MBq·h ± 28.44%), Lesion 3 (4.8 MBq·h ± 17.64%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ramonaheng, K.; Banda, K.; Qebetu, M.; Goorhoo, P.; Legodi, K.; Masogo, T.; Seebarruth, Y.; Mdanda, S.; Sibiya, S.; Mzizi, Y.; et al. Clinical Image-Based Dosimetry of Actinium-225 in Targeted Alpha Therapy. Cancers 2026, 18, 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020321

Ramonaheng K, Banda K, Qebetu M, Goorhoo P, Legodi K, Masogo T, Seebarruth Y, Mdanda S, Sibiya S, Mzizi Y, et al. Clinical Image-Based Dosimetry of Actinium-225 in Targeted Alpha Therapy. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):321. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020321

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamonaheng, Kamo, Kaluzi Banda, Milani Qebetu, Pryaska Goorhoo, Khomotso Legodi, Tshegofatso Masogo, Yashna Seebarruth, Sipho Mdanda, Sandile Sibiya, Yonwaba Mzizi, and et al. 2026. "Clinical Image-Based Dosimetry of Actinium-225 in Targeted Alpha Therapy" Cancers 18, no. 2: 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020321

APA StyleRamonaheng, K., Banda, K., Qebetu, M., Goorhoo, P., Legodi, K., Masogo, T., Seebarruth, Y., Mdanda, S., Sibiya, S., Mzizi, Y., Davis, C., Smith, L., Ndlovu, H., Kabunda, J., Maes, A., Van de Wiele, C., Al-Ibraheem, A., & Sathekge, M. (2026). Clinical Image-Based Dosimetry of Actinium-225 in Targeted Alpha Therapy. Cancers, 18(2), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020321