Detection of Breast Lesions Utilizing iBreast Exam: A Pilot Study Comparison with Clinical Breast Exam

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

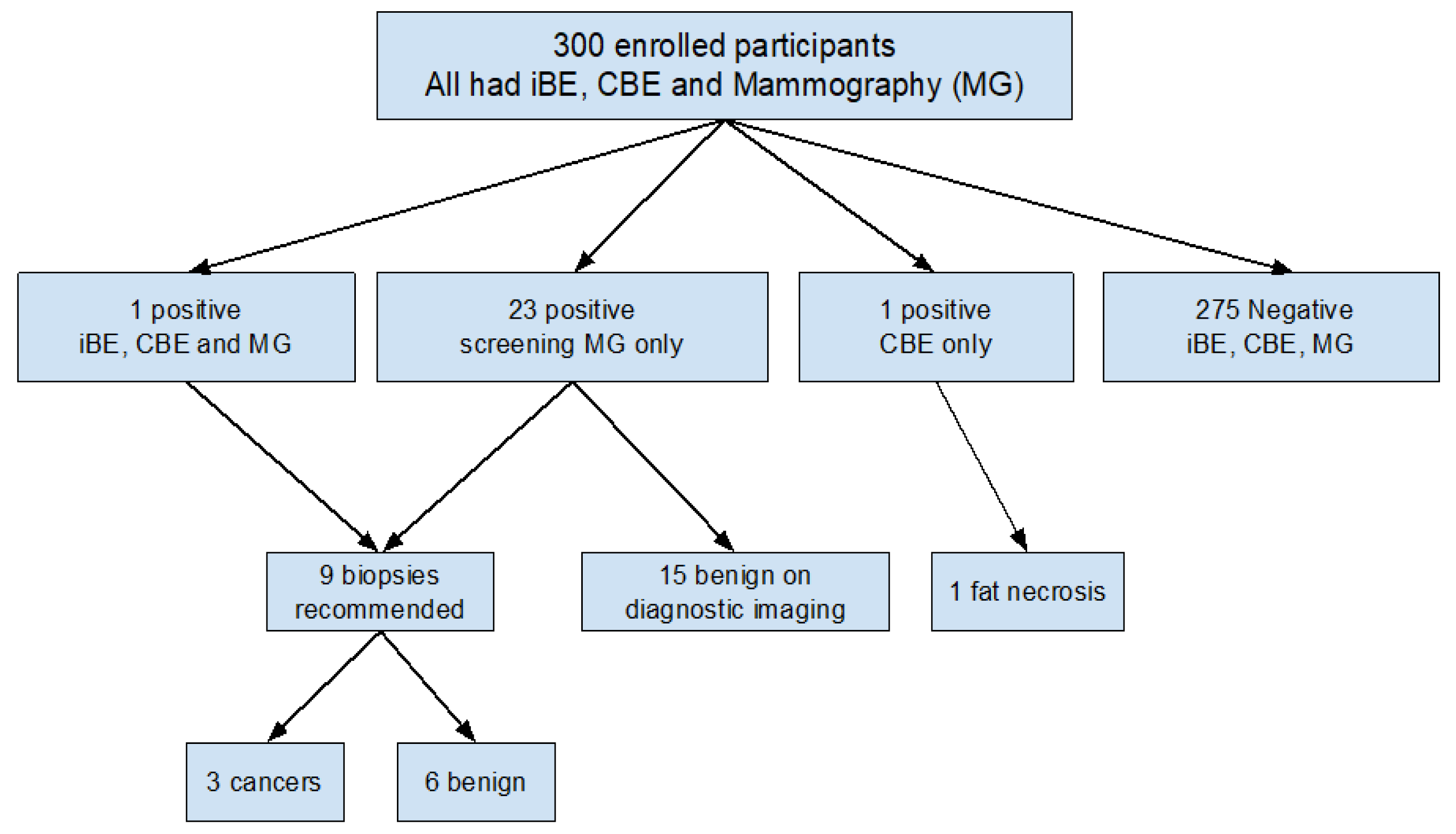

2.1. Overall Study Design

2.2. Clinical Breast Exam

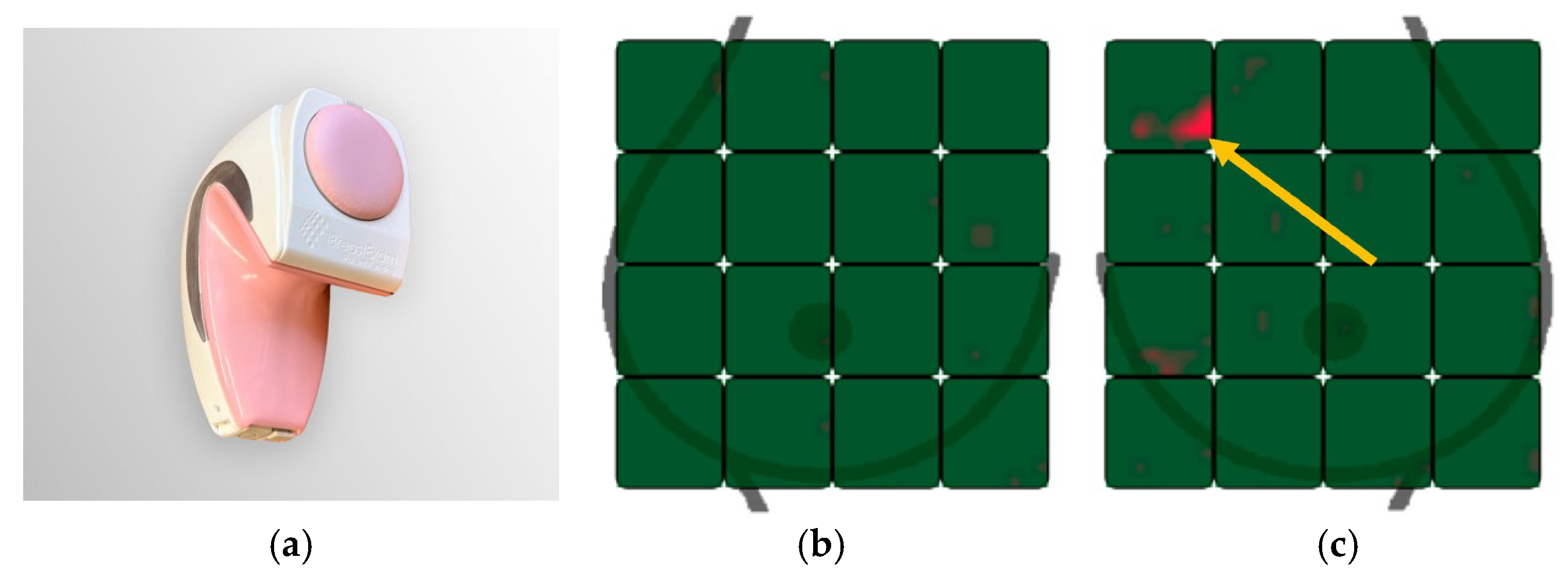

2.3. iBreast Exam

2.4. Breast Imaging

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population

3.2. Breast Exam Results

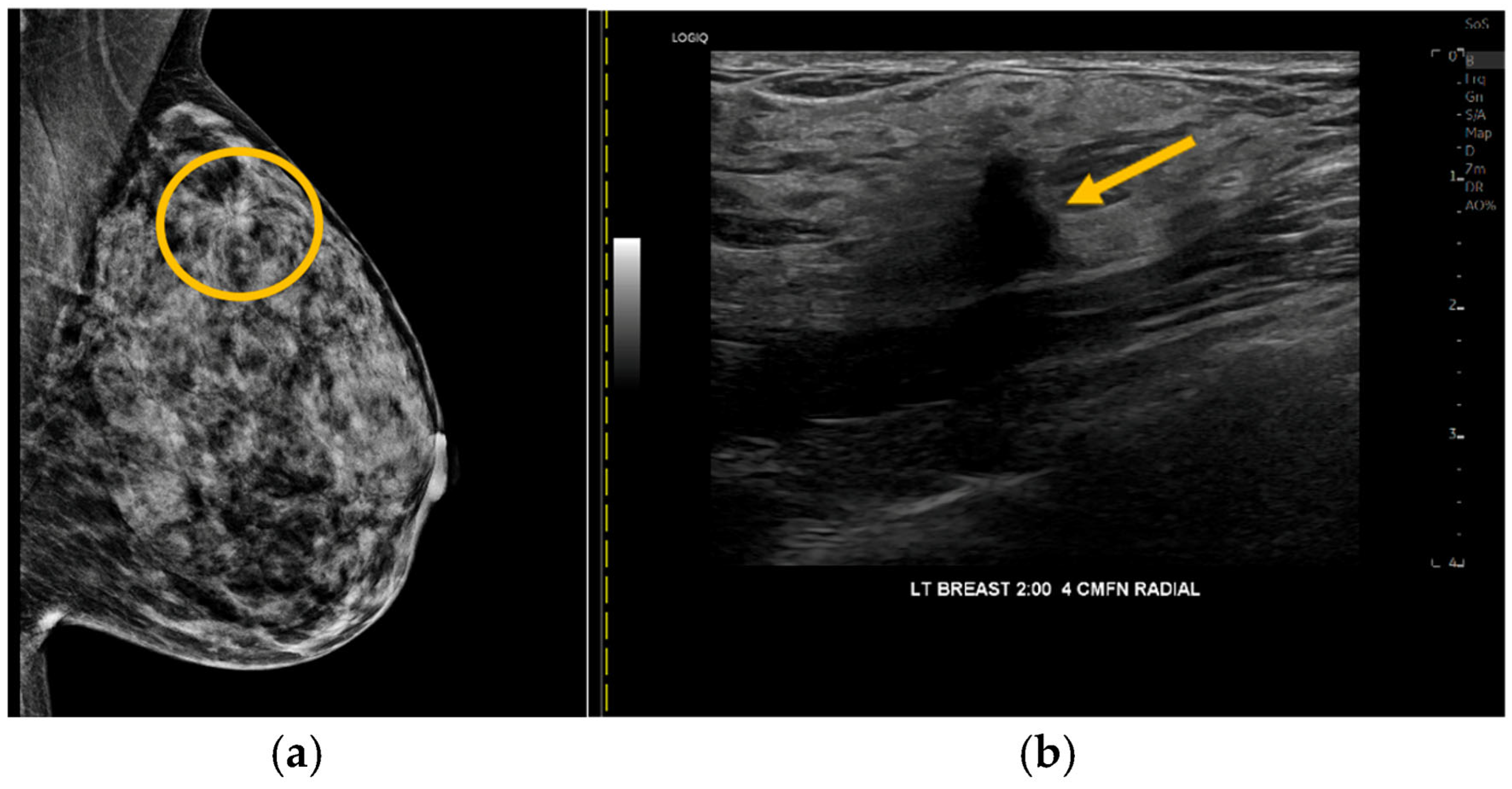

3.3. Biopsy Recommendations and Pathology Results

3.4. Operator Experience with iBE

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| iBE | iBreast Exam |

| CBE | Clinical Breast Exam |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| NP | Nurse Practitioner |

| LMIC | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| MSK | Memorial Sloan Kettering |

| RLC | Ralph Lauren Center |

| RT | Radiology Technologist |

| MG | Mammography |

| IDC | Invasive Ductal Carcinoma |

| DCIS | Ductal Carcinoma in Situ |

| PASH | Pseudoangiomatous Stromal Hyperplasia |

References

- Tabar, L.; Fagerberg, C.J.; Gad, A.; Baldetorp, L.; Holmberg, L.H.; Grontoft, O.; Ljungquist, U.; Lundstrom, B.; Manson, J.C.; Eklund, G.; et al. Reduction in mortality from breast cancer after mass screening with mammography. Randomised trial from the Breast Cancer Screening Working Group of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Lancet 1985, 1, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, I.; Aspegren, K.; Janzon, L.; Landberg, T.; Lindholm, K.; Linell, F.; Ljungberg, O.; Ranstam, J.; Sigfusson, B. Mammographic screening and mortality from breast cancer: The Malmö mammographic screening trial. BMJ 1988, 297, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, S.; Strax, P.; Venet, L. Periodic breast cancer screening in reducing mortality from breast cancer. JAMA 1971, 215, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.A.; Duffy, S.W.; Gabe, R.; Tabar, L.; Yen, A.M.F.; Chen, T.H.H. The randomized trials of breast cancer screening: What have we learned? Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 42, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.T.; Welch, B.T.; Brinjikji, W.; Farah, W.H.; Henrichsen, T.L.; Murad, M.H.; Knudsen, J.M. Racial disparities in screening mammography in the United States: A systemic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2017, 14, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mango, V.L.; Stoeckl, E.M.; Reid, N.J.; Miles, R.C.; Flores, E.J.; Weissman, I.A.; Wagner, A.; Morla, A.; Jose, O.; Narayan, A.K. Impact of High Neighborhood Socioeconomic Deprivation on Access to Accredited Breast Imaging Screening and Diagnostic Facilities. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2023, 20, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, E.; Richmond, R. Improving early detection of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: Why mammography may not be the way forward. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L.A. Breast cancer screening in low and middle-income countries. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 83, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, L.H.; Diaz, S.; Gamboa, O.; Poveda, C.; Henao, A.; Perry, F.; Duggan, C.; Gil, F.; Murillo, R. Accuracy of mammography and clinical breast examination in the implementation of breast cancer screening programs in Columbia. Prev. Med. 2018, 115, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, C.H.; Smith, R.A.; Anderson, B.O.; Miller, A.B.; Thomas, D.B.; Ang, E.S.; Caffarella, R.S.; Corbex, M.; Kreps, G.L.; McTiernan, A.; et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: Early detection resource allocation. Cancer 2008, 113, 2244–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittra, I.; Mishra, G.A.; Dikshit, R.P.; Gupta, S.; Kulkarni, V.Y.; Shaikh, H.K.A.; Shastri, S.S.; Hawaldar, R.; Gupta, S.; Pramesh, C.S.; et al. Effect of screening by clinical breast examination on breast cancer incidence and mortality after 20 years: Prospective, cluster randomized controlled trial in Mumbai. BMJ 2021, 372, n256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, J.J.; Barton, M.B.; Geiger, A.M.; Herrinton, L.J.; Rolnick, S.J.; Harris, E.L.; Barlow, W.E.; Reisch, L.M.; Fletcher, S.W.; Elmore, J.G. Screening clinical breast examination: How often does it miss lethal breast cancer? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2005, 35, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Malmartel, A.; Tron, A.; Caulliez, S. Accuracy of clinical breast examination’s abnormalities for breast cancer screening: Cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 237, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veitch, D.; Goossens, R.; Owen, H.; Veitch, J.; Molenbroek, J.; Bochner, M. Evaluation of conventional training in Clinical Breast Examination (CBE). Work 2019, 62, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Food & Drug Administration. 510(k) Premarket Notification. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K142926 (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- UE Life Sciences Inc. Available online: https://www.ibreastexam.com/ (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Clanahan, J.M.; Reddy, S.; Broach, R.B.; Rositch, A.F.; Anderson, B.O.; Wileyto, E.P.; Englander, B.S.; Brooks, A.D. Clinical utility of a hand-held scanner for breast cancer early detection and patient triaage. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Chung, Y.; Brooks, A.D.; Shih, W.H.; Shih, W.Y. Development of array piezoelectric fingers twoards in vivo breast tumor detection. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2016, 87, 124301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broach, R.B.; Geha, R.; Englander, B.S.; DeLaCruz, L.; Thrash, H.; Brooks, A.D. A cost-effective handheld breast scanner for use in low-resource environments: A validation study. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 14, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, R. Health worker led breast examination in rural India using electro-mechanical hand-held breast palpation device. J. Cancer Prev. Curr. Res. 2018, 9, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Somashekhar, S.; Vijay, R.; Ananthasivan, R.; Prasanna, G. Nonivasive and low-cost technique for early detection of clinically relevant breast lesions using a handheld point-of-care medical device (iBreastExam): Prospective three-arm triple-blinded comparative study. Indian J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gifford-Hollingsworth, C.; Sensenig, R.; Shih, W.H.; Shih, W.Y.; Brooks, A.D. Breast tumor detection using piezoelectric fingers: First clinical report. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2013, 216, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mango, V.L.; Olasehinde, O.; Omisore, A.D.; Wuraola, F.; Famurewa, O.C.; Sevilimedu, V.; Knapp, G.C.; Steinberg, E.; Akinmaye, P.R.; Adewoyin, B.D.; et al. The iBreastExam versus clinical breast examination for breast evaluation in high risk and symptomatic Nigerian women: A prospective study. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, E555–E563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimani, F.; Zhang, J.; Shah, L.; McEvoy, M.; Gupta, A.; Pastoriza, J.; Shihabi, A.; Feldman, S. Can the Clinical Utility of iBreastExam, a Novel Device, Aid in Optimizing Breast Cancer Diagnosis? A Systematic Review. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2023, 9, e2300149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, D.; Cruz, T.; Rania, S.; Badowski, G.; Cassel, K.; Wolfgruber, T.; Grosskreutz, S.; Dulana, L.J.; Adonay, R.; Maskarinec, G.; et al. Technical note: Low clinical efficacy, but good acceptability of a point-of-care electronic palpation device for breast cancer screening for a lower middle-income environment. Med. Phys. 2022, 49, 2663–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncalves, J.; Nogueira, F.; Stock, F.; Martins, F.; Fernandes, I.; Gameiro-Dos-Santos, R.; Gramaca, J.; Trabulo, C.; Angelo, I.; Pina, I. The Clinical Utility of a Hand-Held Piezoelectric Scanner in the Detection of Early Tumor and Changes in Breast Texture. Cereus 2024, 16, e70586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Manning, J.C.; Devaraj, K.; Richards-Kortum, R.R.; McFall, S.M.; Murphy, R.L.; Semeere, A.; Erickson, D. Emerging Trends in Point-of-Care Technology Development for Oncology in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2025, 11, e2500142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neagu, A.N.; Bruno, P.S.; Josan, C.L.; Waterman, N.; Morrissiey, H.; Njoku, V.T.; Darie, C.C. In Search of Ideal Solutions for Cancer Diagnosis: From Conventional Methods to Protein Biomarkers in Liquid Biopsy. Proteomes 2025, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharel, S.; Shrestha, S.; Yadav, S. iBreastExam: Time for Formal Operation in Nepal. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2022, 8, e2200216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MSK Ralph Lauren Center. Available online: https://www.mskcc.org/locations/directory/ralph-lauren-center-cancer-care (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- D’Orsi, C.J.; Sickles, E.A.; Mendelson, E.B.; Morris, E.A. ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System; American College of Radiology: Reston, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rauscher, G.H.; Murphy, A.M.; Qiu, Q.; Dolecek, T.A.; Tossas, K.; Liu, Y.; Alsheik, N.H. The “Sweet Spot” Revisited: Optimal Recall Rates for Cancer Detection With 2D and 3D Digital Screening Mammography in the Metro Chicago Breast Cancer Registry. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021, 216, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omisore, A.D.; Olasehinde, O.; Wuraola, F.O.; Sutton, E.J.; Sevilimedu, V.; Omoyiola, O.Z.; Romanoff, A.; Owoade, I.A.; Olaitan, A.F.; Kingham, T.P.; et al. Improving access to breast cancer screening and treatment in Nigeria: The triple mobile assessment and patient navigation model (NCT05321823): A study protocol. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniolo, J.; Ngoungou, E.B.; Preux, P.M.; Beloni, P. Role and knowledge of nurses in the management of non-communicable diseases in Africa: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Imaging Finding | iBE Results | CBE Results | Biopsy Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malignant | mass | positive | positive | IDC 1 |

| mass | negative | negative | IDC | |

| calcifications | negative | negative | DCIS 2 | |

| Benign | focal asymmetry | negative | negative | PASH 3 |

| mass | negative | negative | Angiolipoma | |

| architectural distortion | negative | negative | Stromal fibrosis | |

| architectural distortion | negative | negative | Radial scar | |

| mass with calcifications | negative | negative | Fibroadenoma | |

| mass | negative | negative | PASH |

| Sensitivity 1 (95% CI) | Specificity 1 (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | PPV (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI-RADS 4 or 5 Imaging Finding (n = 300) | ||||

| iBE | 0.111 (0.003–0.482) | 1.000 (0.987–1.000) | 0.973 (0.948–0.988) | 1.000 (0.025–1.000) |

| CBE | 0.111 (0.003–0.482) | 0.997 (0.981–1.000) | 0.973 (0.948–0.988) | 0.500 (0.013–0.987) |

| p = 0.42 | p = 0.18 | |||

| Breast Cancer (n = 236) | ||||

| iBE | 0.333 (0.008–0.906) | 1.000 (0.984–1.000) | 0.991 (0.970–0.999) | 1.000 (0.025–1.000) |

| CBE | 0.333 (0.008–0.906) | 0.996 (0.976–1.000) | 0.991 (0.970–0.999) | 0.500 (0.0126–0.987) |

| p = 0.99 | p = 0.18 |

| (a) | |||

| Imaging Negative | Imaging Positive | Kappa Value | |

| iBE negative | 291 | 8 | |

| iBE positive | 0 | 1 | 0.195 |

| CBE negative | 290 | 8 | 0.173 |

| CBE positive | 1 | 1 | |

| (b) | |||

| Breast Cancer Negative | Breast Cancer Positive | Kappa Value | |

| iBE negative | 233 | 2 | |

| iBE positive | 0 | 1 | 0.497 |

| CBE negative | 232 | 2 | |

| CBE positive | 1 | 1 | 0.394 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mango, V.L.; Sales, M.; Ortiz, C.; Moreta, J.; Jimenez, J.; Sevilimedu, V.; Kingham, T.P.; Keating, D. Detection of Breast Lesions Utilizing iBreast Exam: A Pilot Study Comparison with Clinical Breast Exam. Cancers 2026, 18, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020281

Mango VL, Sales M, Ortiz C, Moreta J, Jimenez J, Sevilimedu V, Kingham TP, Keating D. Detection of Breast Lesions Utilizing iBreast Exam: A Pilot Study Comparison with Clinical Breast Exam. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020281

Chicago/Turabian StyleMango, Victoria L., Marta Sales, Claudia Ortiz, Jennifer Moreta, Jennifer Jimenez, Varadan Sevilimedu, T. Peter Kingham, and Delia Keating. 2026. "Detection of Breast Lesions Utilizing iBreast Exam: A Pilot Study Comparison with Clinical Breast Exam" Cancers 18, no. 2: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020281

APA StyleMango, V. L., Sales, M., Ortiz, C., Moreta, J., Jimenez, J., Sevilimedu, V., Kingham, T. P., & Keating, D. (2026). Detection of Breast Lesions Utilizing iBreast Exam: A Pilot Study Comparison with Clinical Breast Exam. Cancers, 18(2), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020281