Long-Read Spatial Transcriptomics of Patient-Derived Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Organoids Identifies Heterogeneity and Transcriptional Remodelling Following NUC-7738 Treatment

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PDOs Culture

2.2. 10× Genomics Visium Experiments

2.3. Image Acquisition

2.4. Long-Read Nanopore Sequencing

2.5. Long-Read Nanopore Data Processing

2.6. Spatial Analysis

2.7. Differential Isoform Detection

3. Results

3.1. Spatially Resolved Gene Expression Analysis in Control ccRCC Organoids

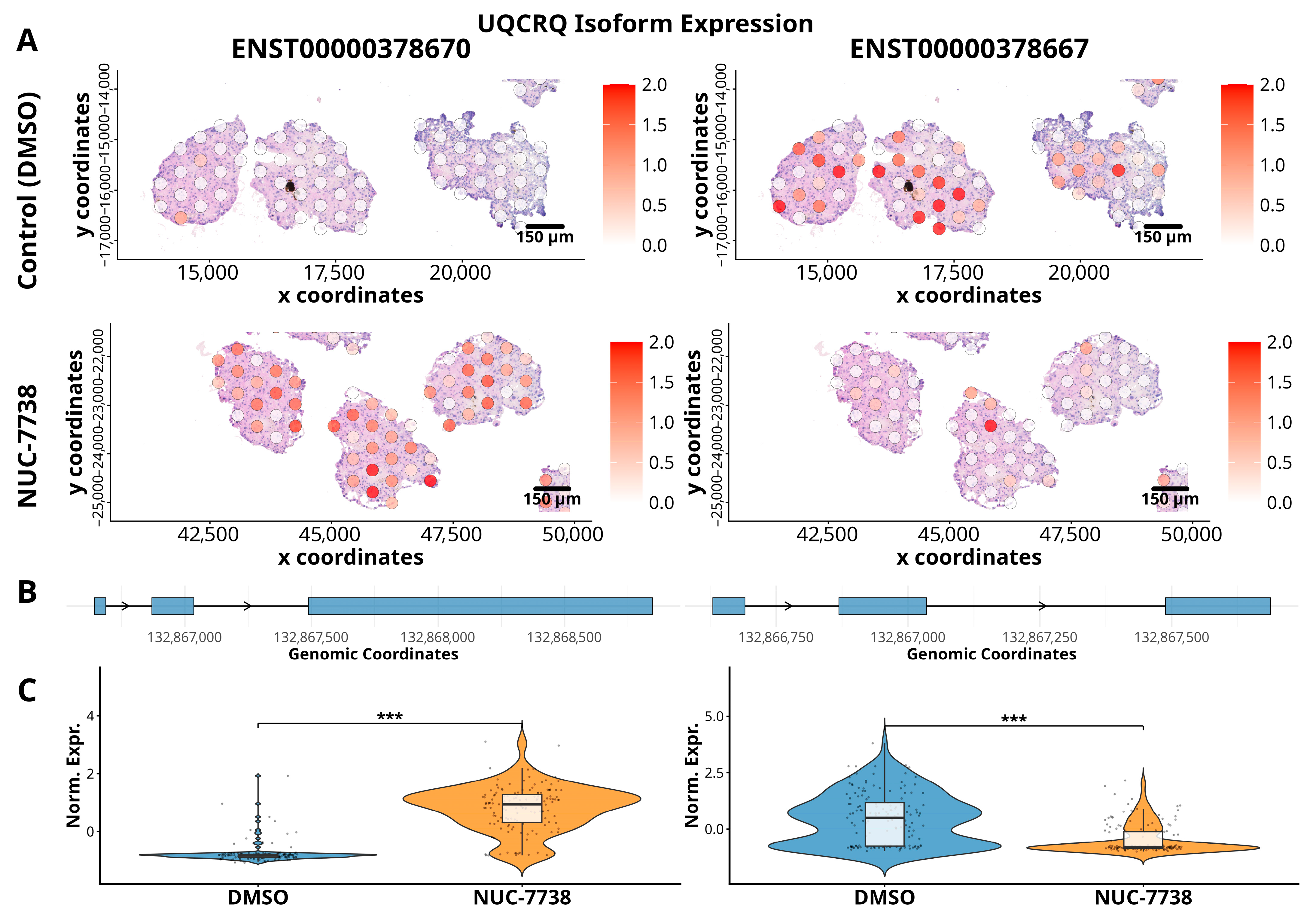

3.2. Gene Isoform Expression in ccRCC Organoids

3.3. Treatment of Organoids with NUC-7738 Demonstrated Marked Changes in Spatial Gene Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Gastaldo, A.; Kempf, E.; del Alba, A.G.; Duran, I. Systemic treatment of renal cell cancer: A comprehensive review. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 60, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, P.C.; Rini, B.I. Treatment of renal cell carcinoma: Current status and future directions. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Wang, L.; Panian, J.; Dhanji, S.; Derweesh, I.; Rose, B.; Bagrodia, A.; McKay, R.R. Treatment Landscape of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2023, 24, 1889–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, K.; He, M.X.; Bakouny, Z.; Kanodia, A.; Napolitano, S.; Wu, J.; Grimaldi, G.; Braun, D.A.; Cuoco, M.S.; Mayorga, A.; et al. Tumor and immune reprogramming during immunotherapy in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 649–661.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhu, J.-J.; Fu, T.-M.; Wu, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, N.; An, Z.; Zheng, W.J. Presence of complete murine viral genome sequences in patient-derived xenografts. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Luo, H.; Wang, S.; Zhou, C.; Li, Z.; Kimhoy, C.; Liang, G.; Chen, S. Renal cell carcinoma organoids for precision medicine: Bridging the gap between models and patients. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, H.; Zickuhr, G.M.; Um, I.H.; Laird, A.; Mullen, P.; Harrison, D.J.; Dickson, A.L. Kidney tumoroid characterisation by spatial mass spectrometry with same-section multiplex immunofluorescence uncovers tumour microenvironment lipid signatures associated with aggressive tumour phenotypes. NPJ Imaging 2025, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Séraudie, I.; Pillet, C.; Cesana, B.; Bazelle, P.; Jeanneret, F.; Evrard, B.; Chalmel, F.; Bouzit, A.; Battail, C.; Long, J.-A.; et al. A new scaffold-free tumoroid model provides a robust preclinical tool to investigate invasion and drug response in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wu, Y.; Shi, Q.; Wu, J.; Kong, D.; Wu, X.; He, X.; Liu, T.; Li, S. Systematic characterization of cancer transcriptome at transcript resolution. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahles, A.; Lehmann, K.-V.; Toussaint, N.C.; Hüser, M.; Stark, S.G.; Sachsenberg, T.; Stegle, O.; Kohlbacher, O.; Sander, C.; Caesar-Johnson, S.J.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Alternative Splicing Across Tumors from 8,705 Patients. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 211–224.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, R.; Cao, C.; Kumar, M.; Sinha, S.; Chanda, A.; McNeil, R.; Samuel, D.; Arora, R.K.; Matthews, T.W.; Chandarana, S.; et al. Spatial transcriptomics reveals distinct and conserved tumor core and edge architectures that predict survival and targeted therapy response. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, R.; Miura, N.; Kurata, M.; Kitazawa, R.; Kikugawa, T.; Saika, T. Spatial Gene Expression Analysis Reveals Characteristic Gene Expression Patterns of De Novo Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer Coexisting with Androgen Receptor Pathway Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Yuan, L.; Danilova, L.; Mo, G.; Zhu, Q.; Deshpande, A.; Bell, A.T.F.; Elisseeff, J.; Popel, A.S.; Anders, R.A.; et al. Spatial transcriptomics analysis of neoadjuvant cabozantinib and nivolumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma identifies independent mechanisms of resistance and recurrence. Genome Med. 2023, 15, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenzer, H.; De Zan, E.; Elshani, M.; van Stiphout, R.; Kudsy, M.; Morris, J.; Ferrari, V.; Um, I.H.; Chettle, J.; Kazmi, F.; et al. The Novel Nucleoside Analogue ProTide NUC-7738 Overcomes Cancer Resistance Mechanisms In Vitro and in a First-In-Human Phase I Clinical Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 6500–6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.G.; Chávez-Fuentes, J.C.; O’Brien, M.; Xu, J.; Ruiz, E.; Wang, W.; Amin, I.; Sarfraz, I.; Guckhool, P.; Sistig, A.; et al. Giotto Suite: A Multi-Scale and Technology-Agnostic Spatial Multi-Omics Analysis Ecosystem. Nat. Methods 2023, 22, 2052–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, A.T.; McCarthy, D.J.; Marioni, J.C. A step-by-step workflow for low-level analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data with Bioconductor. F1000Research 2016, 5, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, M.; Robinson, M.D. DRIMSeq: A Dirichlet-Multinomial Framework for Multivariate Count Outcomes in Genomics. F1000Research 2016, 5, 16356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, I.-J.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Chang, J.-S.; Yang, J.-C.; Chiu, H.-W.; Lin, Y.-F. Lactotransferrin Downregulation Drives the Metastatic Progression in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Che, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, J.; Lei, Y.; Lu, Z.; Sun, N.; He, J. PLAU directs conversion of fibroblasts to inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts, promoting esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression via uPAR/Akt/NF-κB/IL8 pathway. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, C.; Yang, C.; Zheng, Q.; Hou, Y. Tropomyosin-1 Functions as a Tumor Suppressor with Respect to Cell Proliferation, Angiogenesis and Metastasis in Renal Cell Carcinoma. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 2220–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, B.; Yu, T.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Deng, C.; Zhao, B.; Nakanishi, H.; Zhang, X. Involvement of Cathepsins in Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses in Periodontitis. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 4517587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklovicova, S.; Volpini, L.; Sanovec, O.; Monaco, F.; Vanova, K.H.; Novak, J.; Boukalova, S.; Zobalova, R.; Klezl, P.; Tomasetti, M.; et al. Mitochondrial respiratory complex II is altered in renal carcinoma. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1871, 167556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezwada, D.; Perelli, L.; Lesner, N.P.; Cai, L.; Brooks, B.; Wu, Z.; Vu, H.S.; Sondhi, V.; Cassidy, D.L.; Kasitinon, S.; et al. Mitochondrial complex I promotes kidney cancer metastasis. Nature 2024, 633, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Li, T.; Chen, Y.; Ye, S.; Zhou, S.; Tian, X.; Anwaier, A.; Zhu, S.; Xu, W.; Hao, X.; et al. Deciphering glutamine metabolism patterns for malignancy and tumor microenvironment in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoerner, C.R.; Chen, V.J.; Fan, A.C. The ‘Achilles Heel’ of Metabolism in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Glutaminase Inhibition as a Rational Treatment Strategy. Kidney Cancer 2019, 3, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Stalnecker, C.; Zhang, C.; McDermott, L.A.; Iyer, P.; O’neill, J.; Reimer, S.; Cerione, R.A.; Katt, W.P. Characterization of the interactions of potent allosteric inhibitors with glutaminase C, a key enzyme in cancer cell glutamine metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 3535–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsunsky, I.; Millard, N.; Fan, J.; Slowikowski, K.; Zhang, F.; Wei, K.; Baglaenko, Y.; Brenner, M.; Loh, P.-R.; Raychaudhuri, S. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagden, S.P.; Symeonides, S.N.; Skolariki, A.; Haris, N.M.; Boh, Z.; Um, I.H.; Elshani, M.; Dickson, A.L.; Zhang, Y.; Harrison, D.J.; et al. Abstract C032: NUC-7738 in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic melanoma: Phase 2 results from the NuTide:701 study. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2023, 22, C032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, L.K.; Branchi, V.; Leonardelli, S.; Pelusi, N.; Simon, A.G.; Klümper, N.; Ellinger, J.; Hauser, S.; Gonzalez-Carmona, M.A.; Ritter, M.; et al. Cultivation of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Patient-Derived Organoids in an Air-Liquid Interface System as a Tool for Studying Individualized Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, V.S.; Cardona, C.d.J.; Hejret, V.; Tiefenbacher, A.; Mair, T.; Tran, L.; Pfneissl, J.; Draganić, K.; Binder, C.; Kabiljo, J.; et al. Mimicking Tumor Cell Heterogeneity of Colorectal Cancer in a Patient-derived Organoid-Fibroblast Model. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 15, 1391–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, G.; Di Bonito, M.; Cantile, M. Organoid biobanks as a new tool for pre-clinical validation of candidate drug efficacy and safety. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 13, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ooft, S.N.; Weeber, F.; Dijkstra, K.K.; McLean, C.M.; Kaing, S.; Van Werkhoven, E.; Schipper, L.; Hoes, L.; Vis, D.J.; Van De Haar, J.; et al. Patient-derived organoids can predict response to chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaay2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalla, J.; Pfneissl, J.; Mair, T.; Tran, L.; Egger, G. A systematic review on the culture methods and applications of 3D tumoroids for cancer research and personalized medicine. Cell. Oncol. 2024, 48, 38806997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geevimaan, K.; Guo, J.-Y.; Shen, C.-N.; Jiang, J.-K.; Fann, C.S.J.; Hwang, M.-J.; Shui, J.-W.; Lin, H.-T.; Wang, M.-J.; Shih, H.-C.; et al. Patient-Derived Organoid Serves as a Platform for Personalized Chemotherapy in Advanced Colorectal Cancer Patients. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 883437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennig, A.; Baenke, F.; Klimova, A.; Drukewitz, S.; Jahnke, B.; Brückmann, S.; Secci, R.; Winter, C.; Schmäche, T.; Seidlitz, T.; et al. Detecting drug resistance in pancreatic cancer organoids guides optimized chemotherapy treatment. J. Pathol. 2022, 257, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Xu, H.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Meng, Q.; Mei, H.; Cai, Z.; Chen, W.; Huang, W. Patient-derived renal cell carcinoma organoids for personalized cancer therapy. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolck, H.A.; Corrò, C.; Kahraman, A.; von Teichman, A.; Toussaint, N.C.; Kuipers, J.; Chiovaro, F.; Koelzer, V.H.; Pauli, C.; Moritz, W.; et al. Tracing Clonal Dynamics Reveals that Two- and Three-dimensional Patient-derived Cell Models Capture Tumor Heterogeneity of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. Focus 2021, 7, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrigand, K.; Bergenstråhle, J.; Thrane, K.; Mollbrink, A.; Meletis, K.; Barbry, P.; Waldmann, R.; Lundeberg, J. The spatial landscape of gene expression isoforms in tissue sections. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, N.; Lanke, V.; Vinod, P.K. Network-based metabolic characterization of renal cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Balan, M.; Sabarwal, A.; Choueiri, T.K.; Pal, S. Metabolic reprogramming in renal cancer: Events of a metabolic disease. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Rev. Cancer 2021, 1876, 188559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M. Targeting glutamine use in RCC. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 19, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abdullah, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kirkwood, K.; Laird, A.; Mullen, P.; Harrison, D.J.; Elshani, M. Long-Read Spatial Transcriptomics of Patient-Derived Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Organoids Identifies Heterogeneity and Transcriptional Remodelling Following NUC-7738 Treatment. Cancers 2026, 18, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020254

Abdullah H, Zhang Y, Kirkwood K, Laird A, Mullen P, Harrison DJ, Elshani M. Long-Read Spatial Transcriptomics of Patient-Derived Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Organoids Identifies Heterogeneity and Transcriptional Remodelling Following NUC-7738 Treatment. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020254

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdullah, Hazem, Ying Zhang, Kathryn Kirkwood, Alexander Laird, Peter Mullen, David J. Harrison, and Mustafa Elshani. 2026. "Long-Read Spatial Transcriptomics of Patient-Derived Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Organoids Identifies Heterogeneity and Transcriptional Remodelling Following NUC-7738 Treatment" Cancers 18, no. 2: 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020254

APA StyleAbdullah, H., Zhang, Y., Kirkwood, K., Laird, A., Mullen, P., Harrison, D. J., & Elshani, M. (2026). Long-Read Spatial Transcriptomics of Patient-Derived Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Organoids Identifies Heterogeneity and Transcriptional Remodelling Following NUC-7738 Treatment. Cancers, 18(2), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020254