Palliative Performance Scale Predicts Survival in Patients with Bone Metastasis Undergoing Radiotherapy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Material

2.2. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

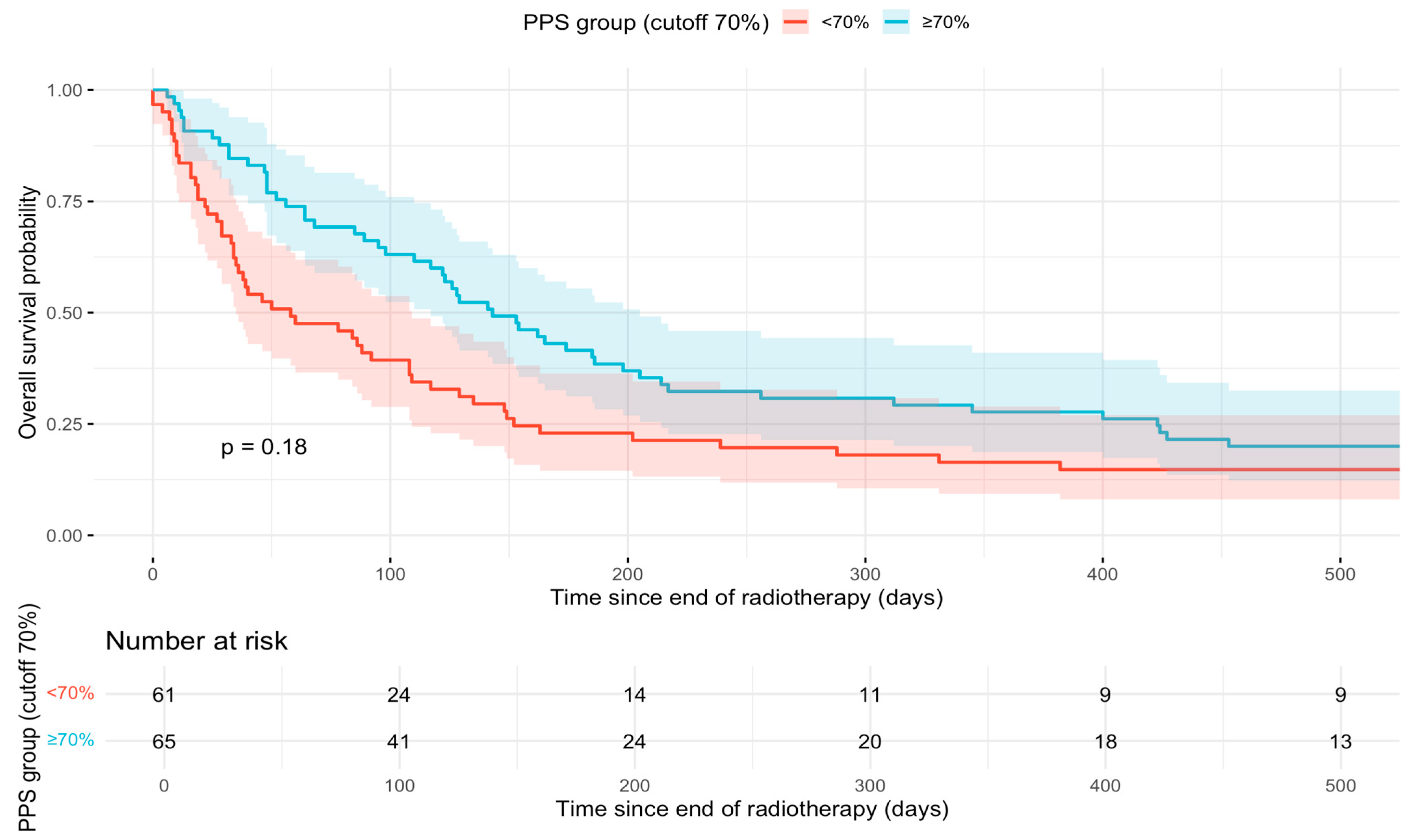

3.2. Survival Analyses

3.3. Logistic Regression Discharge Destination

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| EOL | End-of-Life |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| KPS | Karnofsky Performance Status |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PACS | Picture Archiving and Communication System |

| PPI | Palliative Prognostic Index |

| PPS | Palliative Performance Scale |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SPS | Survival Prediction Score |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getie, A.; Yilak, G.; Ayenew, T.; Amlak, B.T. Palliative care utilisation globally by cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2025, 15, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Hertan, L.; Jones, J. Palliative radiotherapy: Current status and future directions. Semin. Oncol. 2014, 41, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, F.; Downing, G.M.; Hill, J.; Casorso, L.; Lerch, N. Palliative performance scale (PPS): A new tool. J. Palliat. Care 1996, 12, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, F.; Lau, F.; Downing, M.G.; Lesperance, M. A reliability and validity study of the Palliative Performance Scale. BMC Palliat. Care 2008, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafeez, A.A.M.; Makady, N.F.; Hafez, O.; Atallah, C.N.; Alsirafy, S.A. Reliability and validity of the Arabic translation of the palliative performance scale. Palliat. Support. Care 2020, 18, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzierżanowski, T.; Gradalski, T.; Kozlowski, M. Palliative Performance Scale: Cross cultural adaptation and psychometric validation for Polish hospice setting. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oğuz, G.; Şenel, G.; Koçak, N.; Karaca, Ş. The Turkish Validity and Reliability Study of Palliative Performance Scale. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 8, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosich, V.; Andersag, M.; Watzke, H. Frau Doktor, wie lange noch? Die Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) als Hilfsmittel zur Einschätzung der Lebenszeit von PalliativpatientInnen—Validierung einer deutschen Version. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2019, 169, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kock, I.; Mirhosseini, M.; Lau, F.; Thai, V.; Downing, M.; Quan, H.; Lesperance, M.; Yang, J. Conversion of Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG) to Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), and the interchangeability of PPS and KPS in prognostic tools. J. Palliat. Care 2013, 29, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrold, J.; Rickerson, E.; Carroll, J.T.; McGrath, J.; Morales, K.; Kapo, J.; Casarett, D. Is the palliative performance scale a useful predictor of mortality in a heterogeneous hospice population? J. Palliat. Med. 2005, 8, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Ohguri, T.; Matsuki, Y.; Yahara, K.; Narisada, H.; Imada, H.; Korogi, Y. Palliative radiotherapy in patients with a poor performance status: The palliative effect is correlated with prolongation of the survival time. Radiat. Oncol. 2013, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birim, O.; Kappetein, A.P.; Bogers, A.J.J.C. Charlson comorbidity index as a predictor of long-term outcome after surgery for nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2005, 28, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, F.; Cummings, D.E.; Eckel, R.H.; Cohen, R.V.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Brown, W.A.; Stanford, F.C.; Batterham, R.L.; Farooqi, I.S.; Farpour-Lambert, N.J.; et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 221–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allende-Pérez, S.; Rodríguez-Mayoral, O.; Peña-Nieves, A.; Bruera, E. Performance status and survival in cancer patients undergoing palliative care: Retrospective study. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2022, 14, e1256–e1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, D.; Russell, D.; Jordan, L.; Dooley, F.; Bowles, K.H.; Masterson Creber, R.M. Using the Palliative Performance Scale to Estimate Survival for Patients at the End of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Guerriere, D.N.; Zhao, H.; Coyte, P.C. Correlation of Palliative Performance Scale and Survival in Patients with Cancer Receiving Home-Based Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Care 2018, 33, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downing, M.; Lau, F.; Lesperance, M.; Karlson, N.; Shaw, J.; Kuziemsky, C.; Bernard, S.; Hanson, L.; Olajide, L.; Head, B.; et al. Meta-analysis of survival prediction with Palliative Performance Scale. J. Palliat. Care 2007, 23, 245–252; discussion 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prompantakorn, P.; Angkurawaranon, C.; Pinyopornpanish, K.; Chutarattanakul, L.; Aramrat, C.; Pateekhum, C.; Dejkriengkraikul, N. Palliative Performance Scale and survival in patients with cancer and non-cancer diagnoses needing a palliative care consultation: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankun, P.; Saramunee, K.; Chaiyasong, S. Overall Survival and Survival Time by Palliative Performance Scale: A Retrospective Cohort Study in Thailand. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2022, 28, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.-Y.; Wu, H.-Y.; Chan, Y.-H. Revisiting the Palliative Performance Scale: Change in scores during disease trajectory predicts survival. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.-J.; Choi, S.-E.; LeBlanc, T.W.; Suh, S.-Y. Palliative Performance Scale Score at 1 Week After Palliative Care Unit Admission is More Useful for Survival Prediction in Patients with Advanced Cancer in South Korea. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2018, 35, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.J.; Gwak, J.H.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, M.Y.; Kim, S.R.; Chun, S.H.; Jin, J.Y. Changes in the palliative performance scale may be as important as the initial palliative performance scale for predicting survival in terminal cancer patients. Palliat. Support. Care 2021, 19, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, R.B.; Stamm, A.M.N.d.F.; Moritz, R.D.; Freitas, P.F.; Kretzer, L.P.; Gomes, J.V. Serial Palliative Performance Scale Assessment in a University General Hospital: A Pilot Study. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, S.; Zhang, L.; Sinclair, E.; Tsao, M.; Barnes, E.A.; Danjoux, C.; Sahgal, A.; Goh, P.; Culleton, S.; Mitera, G.; et al. The palliative performance scale: Examining its inter-rater reliability in an outpatient palliative radiation oncology clinic. Support. Care Cancer 2009, 17, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewhurst, F.; Stow, D.; Paes, P.; Frew, K.; Hanratty, B. Clinical frailty and performance scale translation in palliative care: Scoping review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2022, 12, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Ross, J.; Park, M.; Dev, R.; Vidal, M.; Liu, D.; Paiva, C.E.; Bruera, E. Predicting survival in patients with advanced cancer in the last weeks of life: How accurate are prognostic models compared to clinicians’ estimates? Palliat. Med. 2020, 34, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.; Kim, A.; Flanagan, J.; Selby, D. Palliative performance scale and survival among outpatients with advanced cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedel, P.; Joosse, L.L.; Jeske, L. Use of the Palliative Performance Scale version 2 in obtaining palliative care consults. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 2012–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiros, E.T.S.P.S.; Da Silva, L.G.S.; de Carvalho Gomes, C.; de Sousa Dantas, J.C.A.; Lopes, M.M.G.D. Association between Palliative Performance Scale and nutritional aspects in individuals with cancer in exclusive palliative care. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 50, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.; Kang, J.H.; Koh, S.-J.; Kim, Y.J.; Seo, S.; Kim, J.H.; Cheon, J.; Kang, E.J.; Song, E.-K.; Nam, E.M.; et al. Early Integrated Palliative Care in Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2426304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, E.; Abdolell, M.; Panzarella, T.; Harris, K.; Bezjak, A.; Warde, P.; Tannock, I. Predictive model for survival in patients with advanced cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 5863–5869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, M.S.; Epstein-Peterson, Z.; Chen, Y.H.; Tseng, Y.D.; Wright, A.A.; Temel, J.S.; Catalano, P.; Balboni, T.A. Predicting life expectancy in patients with metastatic cancer receiving palliative radiotherapy: The TEACHH model. Cancer 2014, 120, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucker, A.; Tsai, C.J.; Loscalzo, J.; Calves, P.; Kao, J. The NEAT Predictive Model for Survival in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 50, 1433–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N = 153 |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 56 (37) |

| Male | 97 (63) |

| Age, years | 67 (IQR 58–76) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 88 (58) |

| Divorced | 15 (9.8) |

| Single | 13 (8.5) |

| Widowed | 18 (12) |

| Unknown | 19 (12) |

| Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), n (%) | |

| ≤50% | 65 (42) |

| ≥60% | 88 (58) |

| Body mass index (BMI), kg/m2 | 24.45 (IQR 21.8–27.0) |

| Missing | 1 |

| BMI category, n (%) | |

| Normal weight | 75 (49) |

| Overweight/obese | 65 (43) |

| Underweight | 12 (7.9) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) | 9 (IQR 6–16) |

| Cancer type, n (%) | |

| Genitourinary | 43 (28) |

| Lung | 35 (23) |

| Breast | 26 (17) |

| Gastrointestinal | 19 (12) |

| Bone and soft tissue | 13 (8.5) |

| Head and neck | 5 (3.3) |

| Hematologic | 5 (3.3) |

| Melanoma | 5 (3.3) |

| Gynecological | 2 (1.3) |

| RT fractionation, n (%) | |

| Hypofractionated (10–12 fractions) | 123 (80) |

| Ultrahypofractionated (5 × 4 Gy) | 29 (19) |

| RT completion | 139 (91) |

| Systemic therapy, n (%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 64 (42) |

| Immunotherapy | 22 (14) |

| Targeted therapy | 17 (11) |

| Endocrine therapy | 3 (2.0) |

| Bone-directed therapy | 8 (5.2) |

| Unknown | 39 (25) |

| Discharge destination, n (%) | |

| Home with specialized outpatient palliative care | 53 (35) |

| Inpatient palliative care | 22 (14) |

| Rehabilitation | 8 (5.2) |

| Acute care/inpatient hospital | 4 (2.6) |

| Death | 3 (2.0) |

| Other/unknown | 63 (41) |

| Univariate and Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Models | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Univariate Cox | Multivariable Cox | |||||

| N | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Sex | 126 | ||||||

| female | — | — | — | — | |||

| male | 1.34 | 0.92, 1.94 | 0.13 | 1.61 | 1.06, 2.46 | 0.027 | |

| Age | 126 | 0.99 | 0.97, 1.00 | 0.11 | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.00 | 0.050 |

| Marital Status | 126 | ||||||

| other | — | — | — | — | |||

| married | 0.96 | 0.67, 1.37 | 0.8 | 1.15 | 0.77, 1.72 | 0.5 | |

| BMI Category | 126 | ||||||

| Normal weight | — | — | — | — | |||

| Underweight | 1.35 | 0.71, 2.57 | 0.4 | 1.27 | 0.66, 2.47 | 0.5 | |

| Overweight/Obese | 0.89 | 0.62, 1.30 | 0.6 | 0.89 | 0.59, 1.34 | 0.6 | |

| PPS | 126 | ||||||

| <60 | — | — | — | — | |||

| ≥60 | 0.75 | 0.52, 1.08 | 0.12 | 0.62 | 0.41, 0.93 | 0.021 | |

| CCI | 126 | ||||||

| ≤10 | — | — | — | — | |||

| ≥11 | 0.98 | 0.65, 1.47 | >0.9 | 1.27 | 0.78, 2.08 | 0.3 | |

| RT Completion | 126 | ||||||

| no | — | — | — | — | |||

| yes | 0.08 | 0.04, 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.03, 0.12 | <0.001 | |

| Cancer Subtype | N | Events (n) | Event Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genitourinary | 43 | 35 | 81.4 |

| Lung | 34 | 30 | 88.2 |

| Breast | 25 | 19 | 76.0 |

| Gastrointestinal | 19 | 18 | 94.7 |

| Bone and soft tissue | 13 | 11 | 84.6 |

| Head and Neck | 5 | 5 | 100 |

| Hematologic | 5 | 2 | 40.0 |

| Melanoma | 5 | 4 | 80.0 |

| Gynecological | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| Characteristic | Univariate Logistic Regression | Multivariable Logistic Regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Sex | 153 | ||||||

| female | — | — | — | — | |||

| male | 1.05 | 0.53, 2.12 | 0.9 | 0.93 | 0.45, 1.93 | 0.8 | |

| Age | 153 | 1.02 | 0.99, 1.05 | 0.2 | 1.03 | 1.00, 1.06 | 0.11 |

| Marital Status | 153 | ||||||

| other | — | — | — | — | |||

| married | 1.52 | 0.77, 3.06 | 0.2 | 1.49 | 0.74, 3.09 | 0.3 | |

| PPS | 153 | ||||||

| <60 | — | — | — | — | |||

| ≥60 | 1.06 | 0.54, 2.10 | 0.9 | 1.11 | 0.54, 2.31 | 0.8 | |

| BMI | 152 | ||||||

| normal | — | — | — | — | |||

| non-normal | 0.81 | 0.41, 1.57 | 0.5 | 0.77 | 0.39, 1.53 | 0.5 | |

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| female | — | — | |

| male | 1.86 | 1.20, 2.88 | 0.006 |

| Age (years) | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.00 | 0.015 |

| Marital status | |||

| other | — | — | |

| married | 0.91 | 0.61, 1.37 | 0.7 |

| BMI Category | |||

| Normal weight | — | — | |

| Underweight | 1.30 | 0.67, 2.51 | 0.4 |

| Overweight/Obese | 0.95 | 0.62, 1.44 | 0.8 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||

| ≤10 | — | — | |

| ≥11 | 1.18 | 0.72, 1.93 | 0.5 |

| RT Completion | |||

| no | — | — | |

| yes | 0.04 | 0.02, 0.10 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hennig, G.; Thrandorf, E.; Vordermark, D.; Müller, J.A. Palliative Performance Scale Predicts Survival in Patients with Bone Metastasis Undergoing Radiotherapy. Cancers 2026, 18, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010061

Hennig G, Thrandorf E, Vordermark D, Müller JA. Palliative Performance Scale Predicts Survival in Patients with Bone Metastasis Undergoing Radiotherapy. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleHennig, Gina, Emma Thrandorf, Dirk Vordermark, and Jörg Andreas Müller. 2026. "Palliative Performance Scale Predicts Survival in Patients with Bone Metastasis Undergoing Radiotherapy" Cancers 18, no. 1: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010061

APA StyleHennig, G., Thrandorf, E., Vordermark, D., & Müller, J. A. (2026). Palliative Performance Scale Predicts Survival in Patients with Bone Metastasis Undergoing Radiotherapy. Cancers, 18(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010061